CHAPTER THREE

BENEVOLENCE

BENEVOLENCE

You have not lived today until you have done something for someone who can never repay you.

—John Bunyan

Benevolence is the disposition to show respect under all circumstances. It embraces a universal regard toward mankind; a tendency toward good; to be conscious of others’ distress with a desire to alleviate it.

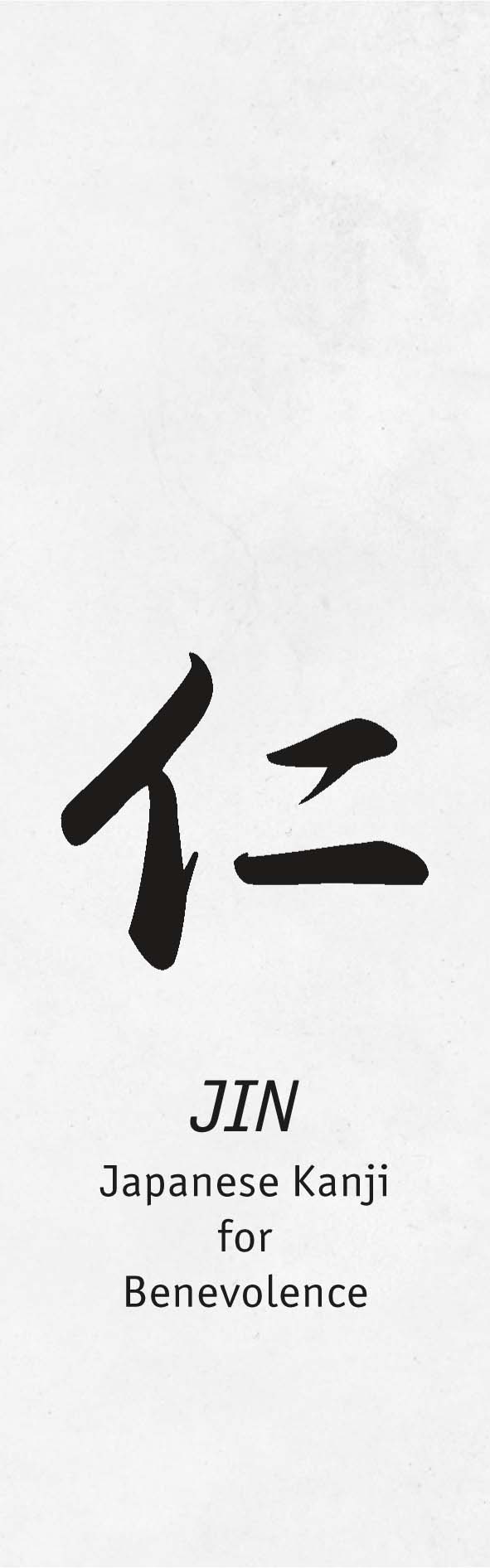

The kanji jin, benevolence, is comprised of two parts: the character on the left side represents a human, or nin, in Japanese, and the character on the right side represents the number two, or ni, in Japanese. The two together comprise the ideogram jin. The kanji literally means “two people.” Its meaning is derived from the Chinese ideogram ren and the Confucian idea of the essence of being human, or the way two people should treat each other. One who is humane is always in a virtuous relationship with other people.

Webster defines benevolence as a disposition to do good, an act of kindness, and a generous gift. The samurai were fierce warriors, yet they demonstrated benevolence toward those they regarded worthy of respect. This principle and virtue set the samurai apart from other warriors of their day.

We live in a fast-paced society with rapidly increasing innovations readily available. Technology is advancing swiftly. Knowledge is increasing at a pace such as the world has never known or experienced. However, despite our increase in technical knowledge, we are still living beings with a heart and soul.

Benevolence is an often misunderstood term today. The concept of benevolence is a form of respect. It is the idea of providing a hand up rather than a hand out.

A wealthy and wise man doesn’t shake hands with people, he gives a helping hand.

_______

Michael Bassey Johnson

The samurai demonstrated benevolence when they defended the weak or allowed a vanquished foe to die an honorable death. In World War II, the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS), comprised entirely of Japanese Americans, interacted with benevolence and compassion to captured Japanese prisoners. Rather than acting harshly, they understood the importance of saving face and befriended their enemies, who were from the land of their parents’ birth; this caused both confusion and compassion. During the reconstruction of Japan after World War II, the MIS became the bridge between the Americans and the Japanese. They understood the language and culture, provided a smoother transition, and contributed to a more successful reconstruction.

An act of kindness, especially toward the less fortunate, is good for the soul. It is a gesture that blesses both the giver and receiver. When we sow seeds of goodness, those seeds will come to fruition in our lives, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Kind hearts are better than fair faces.

_______

Japanese proverb

In America, we are a nation of givers. Many organizations exist to serve others’ needs. We give of our hearts by donating time and money to assist others. Much of this is an acknowledgment of our own blessings and a desire to reach out and aid those less fortunate.

Benevolence was developed in the samurai through engaging in artistic endeavors. Haiku and other forms of writing, storytelling, and drawing required exercising the right side of the brain. It was a balance to the left-brain discipline of the martial arts and war strategies.

As a storyteller, I enjoy sharing Japanese folk tales with young children. Afterward, I ask questions to see if the children grasped the moral of the story. In one particular tale emphasizing kindness, one boy exclaimed, “Be kind!” Those were his only two words, yet so profound. If we would all be kind, imagine what our world would be like.

Mother Teresa personified the benevolent spirit through her dedication to the poorest of the poor in India. It is one thing to have sympathy and pity for the poor, but another to recognize the need and take action to address the condition. In 1979, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Mother Teresa for her devotion to the poor in Calcutta’s slums. Being a humble humanitarian, she did not attend the banquet, but rather requested that the money be donated to the poor in India. How many recipients of prestigious awards have been so modest and generous?

Chiune Sugihara wrote transit visas for the Jews in Lithuania because of his love for humanity. His samurai upbringing influenced his decision and saved countless lives.

In this chapter, we will discover how two men, Dr. Toshio Inahara and Dr. James Okubo, both gave of their gifts and talents for the good of mankind. Maybe you have experienced benevolence at a critical time in your life. It may even have come from an unexpected source. A kind and selfless deed or an act of kindness speaks volumes. Your actions speak louder than words as you do the right thing all the time.

The conqueror is regarded with awe; the wise man commands our respect; but it is only the benevolent man that wins our affection.

_______

William Dean Howells

Inahara Family Kamon

Selfishness leads to nothingness. Generosity and benevolence lead to great reward.

—J.W. Lord

Dr. Toshio Inahara has been a personal family friend since he and my father were young. A world-renowned vascular surgeon, Dr. Inahara’s regard for mankind was aptly demonstrated as he helped my mother and both of my brothers in their latter stages of life.

Dr. Toshio Inahara, born in 1921, spent his early life in Tacoma, where his father was the proprietor of a kashiya (Japanese sweets store). When he started school, he had difficulty speaking English but excelled in math. He enrolled in extracurricular Japanese School, where he learned the Japanese language and memorized 1,200 kanji characters.

Father Inahara desired to raise his five sons in the country, so they relocated to rural western Oregon. It was a culture shock to move from the city to the country, where Inahara attended a one-room grade school with 30 students. He enjoyed the country life, fresh food, and playing sports with his brothers. In their favorite samurai game, the brothers carried wooden swords and reenacted famous battles.

After Pearl Harbor, life drastically changed for Japanese Americans. Inahara volunteered for the U.S. Air Force. Though qualified to be an officer, he, like many other Japanese Americans, was classified as 4-C enemy alien and was ineligible to serve. He sought legal counsel to join the service, but he was denied. After this and because of the impending internment, he petitioned the U.S. government to relocate. The Inahara family was granted the atypical permission to move inland to a farm in Vale, in eastern Oregon.

He wanted to attend college and was accepted at the University of Wisconsin. It was a difficult decision to leave the family farm, but his younger brothers would take over. He graduated in 1946 with a premedical degree from the University of Wisconsin.

Inahara was accepted to the University of Oregon Medical School in 1946, where he met his future wife, Chizuko. He worked as an extern at St. Vincent Hospital in Portland during his senior year. He remained at St. Vincent after graduation in 1951, completing a residency in general surgery and remained there until 1955.

During his last year of training, Dr. Inahara became interested in vascular surgery, a new field coming into prominence. During his early years as a doctor, he encountered several incidents where he could see the need for improved techniques in this area. An opportunity to go to Massachusetts General Hospital, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School, presented itself. As a fellow, he was fortunate to work with Dr. Robert Linton, a leader in the vascular surgical field. During this time, he worked to develop artificial blood vessels and became a board certified vascular surgeon. He returned to St. Vincent Hospital as the first trained vascular surgeon in the state of Oregon.

In 1972, Dr. Inahara formed a fellowship to teach and train vascular surgery to general surgeons at St. Vincent Hospital. Training vascular surgeons was spurred by his desire to spread these new techniques in order to help his fellow man. As the director, he trained 20 vascular surgeons not only from the United States, but Honduras, Australia, and Ireland as well. Dr. Inahara’s aspiration to train his students to be the best was demonstrated in his personal dedication to each individual student over the one-year training period.

His willingness to generously give of his time and knowledge helped not only my family but the whole world. An example of his generosity occurred in 2003 when my younger brother, Dan Tsugawa, was diagnosed with thymus cancer at the age of 46. The medical staff at Southwest Medical Center in Vancouver, Washington, recommended that they perform chemotherapy as soon as possible, although they were not familiar with the effects of this treatment on his condition, or of the outcome.

Uncomfortable with the protocol, Dan contacted Dr. Inahara for a second opinion. Although retired, Dr. Inahara studied Dan’s CAT scans, biopsies, and reports as if he were currently practicing medicine. Dr. Inahara took his case to a study group of 30 to 40 doctors who met at Providence St. Vincent Medical Center in Portland. It was fortunate that thoracic surgeon Anthony Funari was one of the members. A surgical approach addressing the cancer was recommended. As a benevolent gesture, Dr. Inahara was in the operating room during the surgical procedure. The surgery was successful, and Dan’s life was extended.

Dr. Inahara, together with another vascular surgeon and a business partner, patented a carotid shunt in 1982, which was manufactured in 1984. It is an intricate and vital medical device, as he described it:

One of the requirements of vascular surgery is to shunt the circulation while you’re working on the vessel because you’re opening the vessel, but you don’t want to stop the circulation. The lumen (tube) has balloons on either end that occludes the artery while the blood is running through the tube. A balloon, rather than a tourniquet, was used to make the operation safer and more thorough.

The medical devices were named Inahara-Pruitt (“the shorter shunt”) and Pruitt-Inahara (“the longer shunt”). The company has since been sold, and the device is still being manufactured and successfully used in vascular surgeries.

Dr. Inahara’s invention, the Inahara-Pruitt shunt, would be extremely advantageous for my younger sister, Karen Tsugawa. She suffered multiple brain aneurisms and as a result had two emergency surgeries in 2000. Because of Dr. Inahara’s invention, my sister benefited from two successful surgeries and gained a better quality of life.

Dr. Inahara retired as a physician yet he continues to live an active life. On Dad’s berry farm, he picks his own strawberries. He also prepares and cooks Japanese meals for Dad. He enjoys traveling and recently retired from snow skiing in his 90s! His generosity extends beyond the sharing of his medical skills. He and his late wife, Chizuko, also graciously donated to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

Dr. Toshio Inahara is an exemplary example of a physician who took the Hippocratic Oath to heart. Like the samurai, his desire was to do good. He mentored future vascular surgeons, advised family friends, and improved the quality of life for patients; his work even now continues to have an impact. The world is a better place because of one man, Dr. Toshio Inahara, a world-renowned surgeon who cared deeply for his fellow man through his gift of medicine.

Benevolence is the characteristic element of humanity.

_______

Confucius

Medal of Honor

Dedicated in 2002 at Ft. Lewis, Washington, the Okubo Medical and Dental Complex is a befitting tribute to a courageous and heroic man, Dr. James K. Okubo. The exhibit in the building entrance displays Okubo’s life and outstanding service during World War II. Patients and medics in training can view the exhibit, be inspired, and ask themselves if they could respond as gallantly under pressure as Okubo. Would they have enough concern for their fellow man to risk their own lives?

James K. Okubo was born in Anacortes, Washington, in 1920. He volunteered to serve as a medic in the all-nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team of the U.S. Army. He literally risked his life under enemy fire to rescue and treat fellow wounded soldiers in France. For his bravery, he was awarded the Silver Star—the U.S. Army’s third-highest decoration.

In 2000, President Clinton upgraded that Silver Star to the Medal of Honor. The citation explains:

Technician Fifth Grade James K. Okubo distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism in action on 28 and 29 October and 4 November 1944, in the Foret Domaniale de Champ, near Biffontaine, eastern France. On 28 October, under strong enemy fire coming from behind mine fields and roadblocks, Technician Fifth Grade Okubo, a medic, crawled 150 yards to within 40 yards of the enemy lines. Two grenades were thrown at him while he left his last covered position to carry back wounded comrades. Under constant barrages of enemy small arms and machine gun fire, he treated 17 men on 28 October and eight more men on 29 October. On 4 November, Technician Fifth Grade Okubo ran 75 yards under grazing machine gun fire and, while exposed to hostile fire directed at him, evacuated and treated a seriously wounded crewman from a burning tank, who otherwise would have died. Technician Fifth Grade James K. Okubo’s extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit on him, his unit, and the United States Army.

After World War II, Okubo graduated from dental school, married, and raised a family in Detroit. He tragically died in a car accident at the age of 47 in January 1967. Little did his family know about his heroic World War II service on the frontline until the year 2000, when Okubo’s Silver Star was one of only twenty upgraded to the Medal of Honor. Dr. James K. Okubo demonstrated benevolence and compassion by risking his life to save others. Is there any greater calling?