“I’m not the homeless man down on the corner

begging for change. I am anybody

living anywhere U.S.A.”

—Paul, Birmingham, AL

Guilford County, North Carolina, resident Diane Struble wanted readers of her local newspaper to understand that poverty in America has a new face. In 21st-century America, the poor are no longer just the permanently unemployable, the recently incarcerated, or the mentally ill. Disheveled vagrants who push overstuffed, wobbly wheeled carts down abandoned streets, who sleep across sidewalk grates, or who stay in overcrowded shelters are no longer the reigning faces of poverty.

Even after our poverty tour ended, we’re still haunted by the tragic and triumphant stories of Americans grappling with poverty. Diane Struble’s story, which aired on CBS News in late 2011, reinforced our commitment. During the tour we gazed into the eyes and felt the beating hearts of the needy without the distance of a television screen or a Plexiglass shield: We came face to face with poverty. The folk we met were white like Diane; Black like us; brown, yellow, and every other shade. Poverty refused to discriminate on the basis of religious creed or ethnic identity.1

While many whom we met fit what some define as the “old poor” (people who were impoverished before the beginning of the “Great Recession” in late 2007), we were also gathered with shockingly large numbers of the “new poor”—citizens who were once bona fide members of America’s middle class, whose lives have been ravaged by the new economy’s middle class. They are the grandchildren and great grandchildren of a generation that embodied artist Norman Rockwell’s American Dream. They once possessed relatively predictable and reasonably comfortable lives until they were inexplicably cast into a maelstrom of economic dispossession and spiritual despair. When the bottom fell out of the American Dream, the formerly lower, middle, and upper-middle classes found themselves recast in the nightmares of the downtrodden. Their possessions repossessed, gone; their lifestyles drastically altered; their dignity destroyed; and their identities radically transformed. Many now feel inexplicably cursed by something that was never supposed to happen to “them.” They remain sober, indeed somber, faced with the frightening possibility of being destitute in the future and dependent on meager public assistance with no other resources.

Diane Struble’s newspaper op-ed painted a painfully realistic portrait of the new poor. She and her husband Todd had both done all the right things. Both were college-educated; they enjoyed a solidly middle class, combined annual income of $85,000. During the CBS News interview, the couple explained how Todd had lost his job as a paralegal in November 2009, and hadn’t found steady work since. The Strubles have eight children, four of whom still live at home. They get by on Diane’s school teacher salary of $22,000 a year, which is below the poverty line. Diane cashed in her 401(K) plan, and Todd had withdrawn all he could from his pension. At the time of the interview, the couple had about $25 in cash and $100 in the bank. Their 14-year-old son, Ben, recalled how the family ate soup every day for two weeks: “That’s kind of rough,” he confessed.

“When was the last time you cried?” CBS News reporter Byron Pitts asked Diane. Her face resting on her cupped hands, tears clouding her worried hazel eyes, Diane whispered: “Last night.”

“We are the growing edge of poverty,” Todd interjected, adding that they represent the “greater and greater divide between the haves and the have-nots.”

TO HAVE AND TO HAVE-NOT

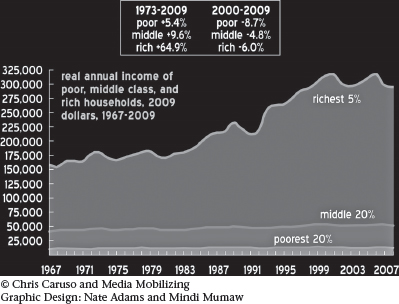

While the incomes of the richest 1 percent of Americans—those earning $380,000 or more—have grown by 33 percent over the past 20 years, the income growth for the other 90 percent of Americans, including the middle class, has been at a virtual standstill. Today, an American “in the top 1 percent takes in an average of $1.3 million per year, while the average American earns just $33,000 per year.”2

Real annual income of poor, middle class & rich

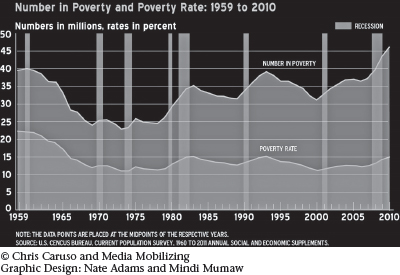

The number of people living in poverty rose by 2.6 million between 2009 and 2010. Revised Census numbers released in 2011 revealed that the number of Americans living in poverty was closer to 50 million. In the Census Bureau’s history of tracking poverty statistics, the Great Recession marked the fourth period of consecutive annual increases in 52 years.

POVERTY TIMELINE

| Year | Poverty Percent |

|

| 1959 | 22.4 percent | Official tracking of the country’s poverty rate begins |

| 1964 | 19.0 percent | President Lyndon B. Johnson declares “War on Poverty” |

| 1969 | 13.7 percent | Johnson’s Great Society efforts help reduce poverty |

| 1973 | 11.1 percent | National poverty rate at an almost 20-year low |

| 1979 | 12.4 percent | Vietnam War, Conservative backlash, poverty ticks up |

| 1983 | 15.2 percent | A recession from mid-1981 to late 1982 takes its toll on the poor |

| 1989 | 13.1 percent | Economy steadies, poverty rate drops in Ronald Reagan’s 2nd term |

| 1992 | 14.5 percent | Reagan drastically slashes government benefit programs, poverty rises |

| 1993 | 15.1 percent | Ten-year gains reversed; Poverty back to 1983 level |

| 1994 | 14.5 percent | Economy perks, poverty level slightly reduced |

| 1996 | 13.7 percent | Poverty rate drops, Clinton introduces drastic welfare reform efforts |

| 2000 | 11.3 percent | Poverty rates fall dramatically due mostly to the opulent 1990s |

| 2007 | 12.5 percent | Poverty ticks up, 37.3 million in poverty before the recession begins |

| 2008 | 13.2 percent | Another 2.5 million fall below the poverty line |

| 2009 | 14.3 percent | 6.3 million more in poverty since 2007 |

| 2010 | 15.1 percent | The largest percentage of long-term poor in five decades |

Number in Poverty and Poverty Rate: 1959 to 2010

The biggest blows to the already shrinking middle class were record unemployment and a housing bubble that burst, resulting in the foreclosure of nearly 4 million homes. In Don Peck’s penetrating investigative piece in The Atlantic, “Can the Middle Class Be Saved?” he explained how the housing boom helped hollow out the middle class by allowing “working-class and middle class families to raise their standard of living despite income stagnation or downward job mobility.”3

The number of Americans who had been unemployed for six months or more in 2009 reached 6.3 million—the largest number since 1948, when the government began counting the long-term unemployed. For the first time in decades, the percentage of working families in poverty rose to 31.2 percent, or 10.2 million people.

We met plenty of skilled people searching for jobs as we traveled from city to city. At Prairie Opportunity, Inc., a Mississippi nonprofit that offers aid and services to the needy, we met folk like Alicia Brooks, a single woman with computer training who had been unemployed for about six months and, at the time, received no income. In Clarksdale, Mississippi, we visited Coahoma Opportunities, Inc., another community service organization, where directors shared heart-breaking stories of clients like Arric Ford, 39, a single father living with his children, ages 13 and 16. Ford, who had been unemployed since March 2011, had been denied unemployment benefits. With no income, he swallowed his pride and turned to Coahoma for help.

During our visit with the University of Wisconsin’s Odyssey Project in Madison, Wisconsin, we met former Chicago resident Kegan Carter. Tall and personable, she graciously invited us to her house for a home-cooked meal. Because of the size of our crew, we declined but were blessed to hear her story. Carter was homeless the first six months after arriving in Madison—pregnant and desperately looking for a new start. While visiting the public library, she happened to notice a flyer for the Odyssey Project—a program that helps low-income adults achieve higher education. She credits the agency for changing her life. It is the reason the single mother of three has earned a degree from the University of Wisconsin in English and plans to go to graduate school.

At the time of our visit, Carter was getting by, making a few bucks designing the project’s newsletter. In a country struggling to find its footing in the competitive, globalized marketplace, prosperous futures for Americans like Carter and others—the unskilled, low-skilled, or even highly skilled—are highly questionable. Manufacturing jobs being outsourced overseas, weakened labor unions, corporations that place profit over working people, and a rapidly growing divide between the rich and the poor have virtually eliminated the middle class: An unprepared America struggles with the specter of an American Dream that is morphing into a distinctively American nightmare.

20TH-CENTURY POVERTY VERSUS

21ST-CENTURY POVERTY

Christopher Jenks, who grew up in a white, middle class family in Minneapolis-St. Paul, had become homeless after his successful career in sales and marketing came to a crashing halt. On the Poverty Tour, we had become fans of the Marguerite Casey Foundation’s Equal Voice Newspaper—an extraordinary online publication dedicated to sharing stories about families living in poverty from multiple perspectives. Equal Voice allowed us to discover Jenks’s plight.

Stubbornly prideful, Jenks refused to apply for public aid while he feverishly sought work. During the hard times, he panhandled on a freeway exit ramp and lived in his car. With no prospects in sight, Jenks finally gave in and applied for government help. Never in his wildest dreams had he imagined himself homeless and surviving on food stamps.

“It’s either that or I die,” Jenks said, “I want a job. So do a lot of other Americans that have been caught up in this tragedy.”

Like Jenks, millions of middle class Americans find themselves caught up in an economic “tragedy” they never imagined could happen to them. Most people living from paycheck to paycheck could probably imagine hard times if they ever lost their jobs; but the middle class’s instant slide into poverty didn’t seem possible, not in America. In a country where hard work, grit, and education have always been touted as the pathway to prosperity and the “American Dream,” living in genuine poverty never entered into most middle class minds.

During the 2012 Republican presidential primary contests, candidates spoke of the poor as if their constituents didn’t include the millions who now fall under the categories of “poor” or “near poor.” Food stamp recipients became the poster children of big government gone awry. Several GOP candidates spoke of overhauling welfare programs, but former House Speaker Newt Gingrich invoked the familiar specter of negative racial stereotypes when he labeled President Barack Obama the “best food stamp President in American history” and called on African Americans in particular to “demand paychecks and not be satisfied with food stamps.”

Ronnie McHugh, of Spring City, Pennsylvania, who happens to be white, was so angered by Gingrich’s comment and the audience’s applause to it that she turned off her TV. At the time, McHugh—a divorcée with no savings and living off an $810 Social Security check every month—wasn’t feeling Gingrich’s charged rhetoric.

“I’d give a million dollars if I could find a job. I’m 64 years old, and no one wants to hire me,” said McHugh.

The debate audience should walk in her shoes, McHugh told a reporter from Equal Voice. If so, perhaps they’d appreciate government programs—any program—that helped hard-working people impacted by the recession.

“I would tell them I had a husband who made $150,000 a year; I had a good salary. We were both laid off at the same time by the same company, and I’ve never been able to rally from that,” McHugh said.4

Situations like hers were addressed during the January 2012 symposium, “Remaking America: From Poverty to Prosperity,” hosted by Tavis and broadcast live on C-SPAN. Barbara Ehrenreich, best-selling author of more than a dozen books, including Nickel and Dimed and Bait and Switch, spoke to present-day attitudes regarding the poor:

“The theory for a long time—coming not only from the right but also from some Democrats—is that poverty means that there’s something wrong with your character, that you’ve got bad habits, you’ve got a bad lifestyle, you’ve made the wrong choices.

“I would like to present an alternative theory … poverty is a shortage of money. And the biggest reason for that shortage of money is that most working people are not paid enough for their work and then we don’t have work.”

Ehrenreich’s observations hits the chord of common sense and speaks to poverty in our times. Unfortunately, politicians and most Americans haven’t made that transition. We react and respond to the poor as if they’re afflicted with some flesh-eating virus and are highly contagious. We deny poverty because we are afraid—afraid that saying the word somehow puts us at risk. We deny poverty because our definitions of it are stuck within a history of bygone eras. This collective psychological black hole of fear threatens so deeply that it often results in moral failure and stalls our efforts to effectively address a potential national pandemic. It paralyzes us and prevents us from courageously facing the facts and coming up with real solutions to help America’s “old” and “new” poor.

This brings us back to Guilford County’s Diane Struble. Her letter to the local newspaper, based on her family’s experience, was an attempt to give voice to the voiceless. In making the distinction between herself and the typical street beggar, Struble was essentially saying that 21st-century poverty is not the 20th-century poverty of our parents’ or grandparents’ generation.5

“THE POOR HOUSE”

There was no official Census taking in America before 1939 when the government started collecting income status information. Consequently, reliable definitions of poverty didn’t exist until the 1960s. Yet even without certified figures, there are several sources, primarily social-reform and charitable agencies, that detail the extent of poverty in America from the 18th to the 20th centuries.

In 1969, researcher William B. Hartley used old Bureau of Labor Statistics, manufacturing records, and other sources to estimate that poverty among wage earners in 1870 was around 62 percent. It dropped to 39 percent in 1900 and rose to 44 percent by 1909.

Before social researchers and women’s organizations in the early 1900s challenged staid perceptions of poverty or “pauperism” in America, poverty was widely blamed on personal flaws such as immorality, alcoholism, and criminal behavior.6 A February 17, 1854, New York Times article depicted the poor as dishonest and criminal and gave no sympathy to their children: “There are ten thousand children in this City alone, who are either without parents or friends, or are trained systematically by their parents to vagrancy, beggary, and crime: not only shut out utterly and hopelessly from all moral influences, but exposed day and night to the contamination of crime …”

During the 19th century, the poor held the same status as prostitutes, thieves, and the criminally insane. Long before the welfare system or the Social Security Administration were established, anyone deemed poor or unable to support themselves were sent to the poorhouse. Modeled after the European system, America’s poorhouses were shelters of horror. The elderly, widows, and their children were housed with society’s outcasts and suffered all sorts of physical neglect and sexual abuse. Local governments provided sparse funding, so residents of all sexes and ages were required to work for their keep, performing tasks that included farming, cooking, laundering, and whatever else was necessary to keep the institutions functioning.

Poorhouses gradually disappeared by the early 20th century as the government established more institutionalized and, arguably, civilized ways to care for the elderly, the sick, the mentally ill, and poor women and children. Nevertheless, the stigma of poverty remained attached to the less fortunate and is still aggressively applied in modern times. Researchers Michael B. Katz and Mark J. Stern, who wrote “Poverty in Twentieth-Century America,” provide an extensive history of poverty in America.7

They introduce social reformer Robert Hunter’s 1904 study, Poverty, that “estimated that half the population of New York City lived in absolute poverty—a number that seems neither an exaggeration nor unrepresentative of other large cities.”8 In the early 1900s, “new immigrants and African-Americans” disproportionately represented the masses of “the poor.” Still, because of “intermittent participation in the workforce,” Katz and Stern noted that about four out of every ten American workers earned poverty wages. Income inequality and poverty worsened between 1896 and 1914 due to cost-of-living increases and declines in the wages of the working poor. Malnourishment and diseases were common. The “real story of widespread, grinding rural poverty,” Katz and Stern noted, “began in the 1920s and continued through the Great Depression.”9

Between the years 1900 and 1920, public opinion about the poor began an incremental shift. This change can be attributed in large part to the Settlement House Movement and bold activism of educated women such as Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, Florence Kelley, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Julia Lathrop, and other founders and directors of settlement houses for the poor.

American settlement houses—private nonprofit agencies—were primarily established in poor immigrant neighborhoods and were modeled after Toynbee Hall in London, England. Inspired by religious convictions and a sense of moral obligation, the agencies were much more than institutions for the destitute. Settlement house leaders became vocal and visible advocates for social-welfare reform, arguing that poverty was not necessarily a character flaw but rather a state of being agitated by multiple factors—slave wages, disease, and the death of a spouse. Advocates challenged newspapers’ attacks on the poor and took on Industrial Age barons accused of exploiting women and children in sweat shops, factories, and mines. In a sense, settlements houses were early America’s think tanks, where recruiting, training, researching, and policy-setting were incorporated into everyday activities. By 1910, about 400 settlement houses were operating in the United States.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was professionally trained in the settlement houses of New York. Her passion and influence had much to do with FDR’s social-reform proposals.

Of course, nothing helped improve the image of poverty like the Stock Market Crash of 1929, which led to the Great Depression. Walking in the shoes of poor folk helped the working class sympathize with those whom they once despised. Like the recession today, during the Depression, working-class folk soon discovered how quickly they, too, could become poor. The social reformers’ often ignored assertions—that systemic and institutional factors contributed to poverty—were finally deemed valid during the Depression era.

Not only were their claims validated, but much of the research, theories, policies, and practices of social reformers and settlement house leaders were incorporated into FDR’s projects and policies, such as his public works programs and Social Security.

POST-WAR POVERTY

Wartime prosperity, rising wages, growth in manufacturing and productivity, declining unemployment, and the expansion of public benefits, all combined, helped to significantly reduce poverty in America in the years after the Depression.

The increased demand for manufacturing products contributed to the transformation of attitudes and roles toward women in the workplace. At the start of World War II, with men by the hundreds of thousands joining the war effort and large and lucrative war contracts waiting to be filled, the United States faced a drastic labor shortage. This void led to the creation of the fictional character “Rosie the Riveter,” a caricature that became part of the propaganda campaign created to entice women out of their homes and into factories, shipyards, and war plants. When the United States entered the war, 12 million women (one-quarter of the workforce) were already working, according to the National Park Service’s exhibit, “Rosie the Riveter: Women Working During World War II.” But, by the end of the war, the number was up to 18 million (one-third of the workforce). All told, between the years 1940 and 1945, female workers in defense industries grew by 462 percent.10

After the war, sexism was re-entrenched in the workplace. Women were either laid off or found themselves (once again) relegated to low-paying jobs. Men basically resumed their dominant positions in the workforce. It wasn’t until 1964 and the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, that women gained the opportunity to exert themselves somewhat equally into the workforce.

We should note the dramatic drop in poverty between the years 1939 and 1959. Census data collected after 1939 showed that by the end of the Great Depression, 40 percent of all working households under the age of 65 earned poverty wages, which were about $900 per year for a family of four. Katz and Stern described a turnaround by 1959, where 60 percent of American householders earned enough money to lift their families out of poverty.11

The dramatic drop in poverty in that 20-year span, however, wasn’t reflected in Black and Hispanic households. Although many Blacks who migrated north after World War II found labor and domestic work, thereby earning more money, the poverty rate in 1939 was still a whopping 71 percent for African Americans and 59 percent for America’s Latino population.12

The 1950s were somewhat prosperous times for the nation, but that decade also marked the beginning of great changes in the American family structure. Households headed by women doubled from 16 percent to 32 percent between 1950 and 1990, but only four out of every ten women who headed households earned more than poverty wages.

The greatest shift in public and political attitudes toward poverty came during the turbulent 1960s in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Michael Harrington’s classic The Other America (1962) forced many Americans to grapple with the conundrum that a country celebrated for its opulence had such glaring income disparities.13 Harrington’s landmark study of poverty in America has been credited as the motivation behind President Johnson’s Great Society policies. Although it was President John F. Kennedy who first came in possession of the book, it was Johnson who used it as a guide for his self-proclaimed “War on Poverty” after Kennedy’s assassination. Harrington’s book was so influential that the Boston Globe and other newspapers wrote that Medicaid, Medicare, food stamps, and the expanded Social Security benefits were all traceable to The Other America.14

The number of families who earned enough to rise out of poverty peaked at 68 percent in 1969. According to Katz and Stern, it dipped again in the 1970s and ’80s and, tragically, by 1989, poverty rates in America were back at 1940-era levels.

Due to the rising cost of living, it became harder for one-salary families to stay above the poverty level. In the late 20th century, it was the increased proportion of married women in the workforce and two-income families that helped keep most American families above the poverty line. On the other end of the spectrum, the poverty rate between male- and female-headed households widened. According to the Katz and Stern report, by 1990, the poverty rate for women in male-headed households was 14 percent while households headed by females stood at the higher rate of 17 percent.15

By the late 1970s, the face of poverty had reverted to 19th-century levels, and the poor were once again blamed for their circumstances. Since then, poverty has become a political football used to accent government failures and ridicule socio-economic outcomes. Also, by focusing on the disproportionate numbers of Blacks and Latinos who live beneath the poverty line, deceitful messengers successfully re-attached the stigma of personal and social irresponsibility to the images of the impoverished.

Over the decades, Americans have become increasingly aware of severe poverty in Third World countries. Starting in the 1970s, televised images have helped Americans distance themselves from the possibility of ever fitting the definition of “poor.” Late-night television commercials present heart-wrenching images of foreign children surrounded by flies, living in villages with no sewers or running water. These depictions of people without sustenance betray the American Dream—the ingrained guarantee of opportunities and success through dogged pursuit of personal wealth. In a nation where instant credit bamboozles consumers, the middle class continues to live in a make-believe bubble of security, forestalling the inevitable based on an elusive promise.

A DREAM DETERRED?

“It’s called the American Dream

because you have to be asleep to believe it.”

—George Carlin

“Between the two of us, my wife and I were making more than $100 grand a year. We lived the middle class highlife of the twos—two salaries, two kids, a two-car garage attached to a four-bedroom house in a nice, quiet neighborhood. Man, we were living the American Dream, but I’m still stunned at how quickly everything changed.”

“Samuel” didn’t want us to use his real name because, he said, he’s well-known in his community—as a Website designer, content provider, and writer. However, he insisted we share his “riches to rags” story.

Both he and his wife are college-educated and had easily found good jobs throughout their careers. In 2009, Samuel lost the full-time job he’d had for six years due to downsizing. But the self-proclaimed “hustler” had already established his own creative-services company. Business was booming—for about six months—until his client base suddenly dried up.

“Major accounts just disappeared. My clients were struggling through the Great Recession like everyone else,” Samuel said. “The phones stopped ringing. No one could afford my services. Bills started piling up quickly. Our annual income was cut in half that first year and by a third in 2010.”

Although he and his wife made decent money, Samuel explained, they still lived “paycheck to paycheck” and had quickly depleted their savings.

Over 50 job queries went unanswered. The couple could no longer afford private-school tuition and had no choice but to place their children in a “substandard” public school, Samuel said. By the end of 2010, cars had been repossessed; the house was in foreclosure; and he found himself in court “a lot” mostly dealing with back taxes and credit card debt. Family tension was high. The economic ruin culminated with the dissolution of his 15-year marriage. At the age of 50, Samuel, a devastated divorcé, says he finds himself reliving the impoverished days of his early adult life:

“Every day, a bill collector will call and remind me that my lack of money means I’m now a ‘loser’ or a ‘deadbeat.’ I live the life of a coward—afraid to answer my own door out of fear that a bill collector or someone who’s come to shut off one of my utilities will be standing there. It’s hard to see myself as a contributing member of society or as a good provider now. My pride, my sense of manhood has been nearly destroyed, man.”

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The presumed scenaro is that you follow all the rules. Everybody knows you can’t be successful in these modern times without a college education. So you enroll in college, perhaps you attend a land-grant state college or a prestigious private university. Perhaps you graduated with honors. Debt might have been pouring out of your ears, but still, you make it. With expectations of a fantastic job that matches your fantastic skills, you’ll handle the debt—later.

Then, reality hits; you can’t find a job in this Recession Economy or the one you secured has been snatched away. You hit the streets, search the want ads and the Internet and newspapers, and social-media sites—nothing.

All seems hopeless. Your life is consumed with massive debt, color-coded bills, and constant calls from malicious debt collectors. You start to lose the symbols of solvency—the car, the house, the financial freedom, and the life you were promised if you played by the rules.

Welcome to the ranks of the poor.

What happened to the American Dream—the one we’ve heard about since kindergarten, the one we’ve read about and were indoctrinated to believe in—the ever-so-plausible happy ending that could be secured with nothing more than a little sweat and dogged determination?

We could, as did comedian George Carlin, cynically dismiss the dream as a myth created by the high-faluting founders of this country. But that would be facile and untrue. Our belief is in the validity of Martin Luther King’s dream, which is a dialectical critique of the American Dream. King’s dream affirmed the humanity of those overlooked and left out by those in power. So, his dream was deeply rooted in the American Dream but placed a premium on poor people. That said, the American Dream is our nation’s brand. It is the strategic marketing plan that has lured millions of immigrants to these shores with hopes of accomplishing wonders unimaginable in their native lands. It is the symbol of our historic rise to a world power in less than 200 years. Yet, the “dream” is not the real problem. America’s denial is. Just as we still adhere to an outdated conception of poverty, we have brought ourselves and our society to the brink by our refusal to draft a new dream for our times. If we don our historical lens, we’ll see a once-democratic vision now compromised and corrupted by materialism and greed that has morphed into an insatiable, capitalist monster that threatens our very existence.

This was the dream of 17th-century Puritans who fled religious persecution in England seeking freedom and opportunities in the “New World.” Yet “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as “unalienable rights” bestowed by God in the Declaration of Independence seems at odds with America’s original sins—genocide against Amerindians and enslavement of Africans.

The dream of equality, hope, and liberty was woven deeply into the fabric of America. The Statue of Liberty gifted to the United States and erected in 1886 personified the country’s ideal values—despite the legal exclusion of Chinese that same year. Millions of New York–bound immigrants were welcomed with these generous words inscribed at Lady Liberty’s feet: “Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Ironically, it wasn’t until 1931, when historian James Truslow Adams penned the “American Dream” in The Epic of America that the phrase became popular enough to become the nation’s mantra.16

As America became more prosperous and powerful, the visionary goals of comforting the poor were drowned out by the bombastic drumbeat for war and the seemingly irresistible cadence of the pursuit of materialistic reward.

America’s “Industrial Age” in the 19th century created some of the country’s first millionaires. Along with improved systems of transportation, communication, banking, machinery, and mass production came mass exploitation of poor men, women, and children. In a very real sense, the Puritans’ benevolent wish for “better and richer and fuller” lifestyles for the common man evolved into an exclusive materialistic hymnal for the rich.

“There has been something crude and heartless and unfeeling in our haste to succeed and be great,” President Woodrow Wilson declared in 1913 at the beginning of the 20th century—himself both a courageous critic of corporate power and exemplary racist and expander of the U.S. empire. “We have squandered a great part of what we might have used, and have not stopped to conserve the exceeding bounty of nature, without which our genius for enterprise would have been worthless and impotent.”17

Vanity Fair’s contributing editor, David Kamp, offered an excellent analysis of the genesis and transformation of the American Dream in “Rethinking the American Dream” (April 2009). By the start of World War II, Kamp noted how the tenets of the American Dream had been incorporated into the rallying cries for war.18

In his 1941 pre-war State of the Union address, Roosevelt declared that the United States would be fighting for: “freedom of speech and expression”; “freedom of every person to worship God in his own way”; “freedom from want”; and “freedom from fear.”

Roosevelt upheld “the ‘American way’ as a model for other nations to follow,” Kamp wrote, adding that Roosevelt also “presented the four freedoms not as the lofty principles of a benevolent super race but as the homespun, bedrock values of a good, hardworking, un-extravagant people.”

Although the American Dream had been compromised by the rich and war-ready, it remained a symbol of basic freedoms and necessities. Thousands of returning veterans in 1944 were able to attend college and become homeowners, thanks to paid tuition and low-interest loans through the G.I. Bill. These benefits during “a severe housing shortage and a boom in young families,” Kamp noted, led to the “rapid-fire development of suburbia.”

Up until the late 1940s, the average white family’s ideal aspirations were attainable. With a house; a car; and one working parent with a decent-paying, benefit-providing job; 20th-century Americans had a good shot at achieving a modest version of the American Dream.

Unfortunately, with the advent of television, the dream became a manipulative marketing tool used to spark unprecedented consumerism. With television programs as benchmarks, we can chart the public depictions of family, for example, from the working-class environment of Ralph and Alice in The Honeymooners to the opulent lifestyles of J. R. and his broods in the 1970s television show Dallas. Fast-forward three more decades, and we’re overwhelmed with a litany of lavish, decadent, and over-indulgent unreal reality shows.

During the late 1950s, as televisions became more affordable, credit cards also hit the consumer market. Suddenly, a working-class society that had been used to paying with cash had the ability to instantly obtain the products, services, and luxuries beamed into their living rooms every night.

Commenting on this societal shift of the late 1950s, Kamp wrote:

“What unfolded over the next generation was the greatest standard-of-living upgrade that this country had ever experienced: an economic sea change powered by the middle class’s newly sophisticated engagement in personal finance via credit cards, mutual funds, and discount brokerage houses—and its willingness to take on debt.”19

The 21st-century American Dream had been defined by wealth and unpredictable lottery-type success. Most of us can’t afford the looks and lifestyles of J-Lo, the Kardashians, Sean (P-Diddy) Combs, or Justin Bieber. But, with our credit cards in hand and a quick trip to the nearest retail outlet, we think we can come darn close with the purchase of their fragrances, jewelry, and clothing lines, as well as by donning their hair styles.

The 21st-century American Dream had been defined by wealth, power, and success. Folks from humble backgrounds who get paid big time for writing best-selling novels, making Oscar-winning films, excelling in golf, winning the title of “American Idol,” or becoming President of the United States are said to have “achieved the American Dream.”

For the rest of us, our parents’ and grandparents’ dream has become unattainable in the 21st century. Infected by the country’s historic motto, we were duped into leveraging all in an illusory pursuit of a marketed “better and richer and fuller” life.

According to the “MetLife Study of the American Dream,” released in 2011, Americans are at a crossroads. We are still “driven by one tenet of American progress—that hard work will get you ahead,” but that belief has been shaken to the core by the intense economic downturn. According to the report, Americans are no longer seeking personal wealth; they are just looking for “a sense of financial security that allows them to live a sustainable lifestyle.”20

If we are to get to a place of shared security, we must first confront some cold, hard facts. Our chickens have come home to roost. While we maligned and ignored the poor and worked to separate them from those more fortunate, poverty snaked its way into mainstream America. As unemployment, corporate greed, and the divide between the rich and the rest of us grew exponentially in the 21st century, we held onto our stale 20th century habits.

To get out of this economic mess, we must thoroughly dissect the missing pieces that placed almost 50 million of us in this calamitous position. Greedy and gluttonous individuals and institutions must be exposed and brought to justice. We have to dissect the poverty of collective actions and thought that got us into this predicament and vow to do better. Lastly, we must map out a bold and courageous path for change—by all means necessary.

After we’ve done these things and more—then and only then can we craft a truly equitable and inclusive course to the American Dream.