RACE AND CULTURE IN AN EVER-CHANGING SOUTH

The general editors have chosen a passage from Absalom, Absalom! for the epigraph to introduce these volumes on southern culture, suggesting thereby that our enduring image of the American South is best captured in the fiction of William Faulkner. Faulkner portrays a place, as C. Vann Woodward once suggested, long haunted by a very un-American memory of defeat, a sense of social failure, a lost innocence. Enveloping his tales is the fear that the South’s best days are in the past, a past that yet haunts and constrains the present, a past that’s “not even past.” The South’s story, then, cannot be simply told; it must be unraveled, strand-by-strand. Indeed, the very rhythm of Faulkner’s storytelling evokes at times an image one often finds in the popular imaginary: the South is an insular, bounded space, a world closed and relatively homogeneous.

In reality, however, Faulkner’s mythic South is a far more nuanced and complex world than its conventional image, with a complicated racial landscape that a simple black and white palette cannot capture. At the center of Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! saga, of course, are the relations between its black and white inhabitants, with the sins of slavery laying heavily on southern white consciences, not because of its brutality and exploitation of labor—which continued under new forms of labor control well into the 20th century—but because of the shame and confusion of the “miscegenated” bodies and cultures left in its wake. At the story’s margins, however, are the descendants of Native Americans, some of them forcibly relocated along a Trail of Tears from the Southeast. Their blood flows in the veins of his black and white characters alike, and their dispossession forms a half-remembered episode in the region’s guilty past. Faulkner’s South also has links to the Caribbean, prefiguring in fiction the flow of people and ideas in real life that would challenge the region’s ostensibly strict social separation of black and white. Upon second sight, then, Faulkner’s South is not closed and insular but open, not bounded and homogeneous but overlapping and diverse. Viewed from that perspective, the region’s racial past and future look very different.

More than a quarter century ago, historian Ira Berlin warned that our understanding of African American life and history was unduly limited by “a static and singular vision” of its dynamics and complexity, when in fact the black experience evolved divergently in different times and spaces. His argument for a revised perspective on black life, one attentive to its spatially and temporally “specific social circumstances and cultural traditions,” applies with equal force to studies of the South as a whole and to its racial dynamics in particular. The essays in this volume underscore Berlin’s charge that we must take serious account of time and space in our efforts to comprehend how ideas about racial difference have shaped the region’s past and present. They make clear that the South is not simply biracial but multiracial, and has been so since the 17th and 18th centuries, when European settlers first deployed captive African labor to exploit confiscated Native American land. They show how a rich, ever-expanding racial diversity has nourished the social and material roots of the South’s proud cultural heritage—of story and song, of architecture and art, of manners and cuisines. They suggest that the region’s political, social, and economic history cannot be fully comprehended without taking account of this past and this present.

Susan O’Donovan elaborates how slavery—the institutional foundation of southern life and culture and of their racial scaffolding—evolved differently in the various subregions of the South and at different historical moments. The South’s racial and labor relations varied over time and space, reflecting the historically specific demographic configurations of its black, white, and red inhabitants, as well as the diversity of the southern economy that evolved. The South and its race relations must be understood in this broader, more dynamic context: that from the beginning the region has been defined by and formed in relation to other slave regimes in the Americas and around the bell curve of the Atlantic slave trade that peaked in the late 18th century; by trade relations with European nations and their Caribbean colonies, both before and after slave emancipation; and by the specific geopolitical interests that all these relationships produced. The South was not and could never be, as the popular imagination would have it, an undifferentiated place, frozen in time.

Focusing on New Orleans as a simultaneously unique and exemplary case, Shannon Dawdy and Zada Johnson reveal how an ostensibly insular southern world had in fact long been open to influences from the larger Atlantic World. Indeed, as their entry and other entries in this volume will show, from the beginning the region was shaped and reshaped by crosscurrents of peoples, ideas, and institutions. Slavery and the slave trade dictated the course of those crosscurrents over the South’s first two and a half centuries, during which black bondage was the core institution around which much of the region’s law, labor, polity, and social life revolved. It was slavery that initially knit the South into the international economic and cultural complex formed by other slave societies in the southern hemisphere, especially in the Caribbean. Sharing similarities in climate, economy, and cultural development, New World slave societies developed similar interests, confronted similar political forces, and evolved similar ideologies of rule and social order. Thus, while “peculiar” in comparison to its northern and middle Atlantic compatriots, the South was not exceptional among its neighbors in the southern Atlantic. It is not surprising, then, that southerners looked to annex Cuba when their farther westward continental expansion seemed thwarted, or that defeated Confederates immigrated to Mexico and Brazil after the Civil War.

Fed by the Atlantic slave trade for all but 50 years of its first two and a half centuries, the South’s population mix and cultural life—for blacks and whites alike—was in constant flux as new Africans poured in and their new owners remade the southern physical and social landscape in order to exploit their labor power. Given that overseas trade was essential to the plantation economy, moreover, southern ports—dotting a coastline stretching from Baltimore to Galveston, the longest in the continental United States—were openings to the world. Through these openings poured goods, people, and, occasionally, revolutionary ideas. Notwithstanding determined efforts to suppress challenges to the racial regime, therefore, the antislavery pamphlets of David Walker or the republican ideas of Haitian and Cuban refugees found their way through those openings.

For all these reasons, British colonies in the lower South manifested from the start a demographic profile and a legal and economic character more typical of the Caribbean and Latin American slave societies than the Chesapeake or northern colonies; and this produced similarities in their political cultures and social arrangements, not least of which was the relative acceptance and allocation of social space to a mixed-race population (as Faulkner shows so graphically in Absalom, Absalom!). The long and porous sea border on the southern Atlantic opened the South to repeated waves of diverse political and economic refugees from the Caribbean basin and, on occasion, invited southern planters to dream of expansion into the Caribbean. All in all, the region knew a dynamism and openness thoroughly at odds with its more conventional image of timelessness and homogeneity.

Moon-Ho Jung’s essay alerts us to the South’s historic links to the Pacific World as well as to the Atlantic, despite the absence of a port on America’s western coast. Like most New World planters, white southerners looked to Asian laborers to replace their former slaves in the early years following the Civil War and slavery’s destruction. The indentured laborers they brought from southern China never satisfied the planters’ fantasies of docile “guest workers” who would stake no claims to economic justice or citizenship, however. Like black freedpeople, Asians came to call the South “home.” They formed families and communities, and some of them mixed socially and biologically with southern blacks, whites, Creoles, and Native Americans. Southern census takers and neighbors were never quite certain how to classify these families racially, so they were all identified simply as “Chinese” until Jim Crow laws forced them onto one or the other side of the biracial spectrum.

This 19th-century Asian beachhead was relatively small and inconsequential to the broader development of the southern economy and society at the time, but it prefigured the pattern of the South’s 20th-century engagement with the Pacific World and a future immigration and settlement pattern that would eventually transform the South’s cultural and racial makeup. From Japan to Vietnam, 20th-century wars in the Pacific drew the United States into intense and continuing involvements with Asian nations and peoples, some of whom made their way to the southern states. Several of the places of wartime incarceration of Japanese American citizens were located in the South—namely, in Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana—from which many of the menfolk were inducted into segregated military units. Three decades later, American military interventions in Southeast Asia resulted in thousands of displaced persons seeking refuge in southern states. New communities sprang up in Louisiana and Texas, where climate, occupational opportunities, and a welcoming Catholic Church encouraged Vietnamese refugees to settle. As a result, the Gulf Coast is now home to more than 200,000 Southeast Asians (Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian) alone, and there were a total of at least 2.3 million Asians scattered across the South by the beginning of the new millennium in 2000. By the early 21st century, peoples of Asian origin had become a ubiquitous presence in southern interior cities and towns—running hotels, restaurants, and other small businesses and building churches, suburban enclaves, and shopping centers—and, in a throwback to the 19th century, sometimes working for manufacturers intent on disrupting union solidarity by employing a presumably docile, non-English-speaking labor force.

The growth of the South’s Asian population is impressive, but the expansion and dispersion of the Latino population is undoubtedly the driving force in the region’s late 20th-century racial transformation. Between 1980 and 2000, the South’s Latino population increased from 4.3 million to 11 million. By the second decade of the new century, their numbers had swelled to 16.4 million. Equally impressive was their far-greater dispersion across the region. Instead of 9 out of 10 being concentrated in Florida and Texas, as had been the case in 1980, Latinos were scattered throughout the southern states in urban and rural areas and occupations.

Although the growing presence of Latinos in many areas of the Old South is new, Spanish-speaking peoples and territories have shaped southern history from the beginning. Imperial Spain’s presence in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in Louisiana profoundly influenced the nation’s and the region’s colonial and early national history. The refuge that Native Americans and escaped African and African American slaves found in Spanish territories left deep impressions on each of those peoples’ cultures, including the cultural interactions and alliances between them that contact promoted. The Latino imprint would grow broader and deeper after the Mexican War of 1846 and the annexation of Texas, both of which were promoted by southern expansionists seeking to build a more impregnable slave empire. Not only did territorial expansion forever blur the regional boundary between South and West; it also provided a rehearsal of a multiracial South, as black labor and brown labor were marshaled to tame the new frontier. With the development of large-scale agriculture in south Texas after World War I, southern plantation–style relations between growers and laborers took on new forms in the context of cross-border migrations by Mexican laborers, which were alternately facilitated and shut down by an expanding border patrol. Like African Americans in states to Texas’s east, people of Mexican origin in south Texas were confronted by the threat of racial violence in addition to segregation. Though lacking the legal mandate for Jim Crow generally inscribed in the constitutions of the southeastern states, the segregation of Mexican Americans in Texas was just as thorough.

The 21st-century legacy of the South’s westward expansion is a far more complex racial situation than the conventional biracial paradigm can account for. The ostensibly “solid” political South now cloaks a social, cultural, and political diversity and complexity that is almost certain to find expression eventually in a new southern political regime. The recent hostility to Mexican immigrants in the southern interior is but a harbinger of that very different political future, since Latino population growth will inevitably change not only the South’s political calculus but its racial discourse as well. It is possible, however, that the South’s rapidly evolving racial demography will also produce more complex political alliances—ones in which black may ally with brown, or brown with white, or even black with white. The 2007 election in Louisiana of a governor and a congressman of Asian descent and conservative politics suggests something of the uncertain trajectory that a reframed political landscape in a multiracial South might take.

With the question “Where did the Asian sit on the segregated bus?” Leslie Bow frames an intriguing perspective on how demographic transformations have challenged, changed, and reinforced southern racial hierarchies. At times, Asians were bystanders to a humiliation directed solely at blacks; at other times they were its victims; and at yet others their status was indeterminate. It was not the first nor the last time that a racial regime built to justify the subordination of black labor had trouble assimilating a nonwhite people of a different origin and history. Mexican Americans, armed with treaty rights and legally classified as white, presented similar problems early on. Similarly, southern Jews, as Allison Schottenstein shows, often had trouble finding their place within the southern racial classification system, the nature of their inclusion or exclusion from whiteness varying sharply from one era to the next.

The problem of finding a place to sit or stand in the racial order has been no less difficult for the racialized victims of that order. At various times, Mexican Americans and Asian Americans have benefited from their legal designation as “white,” notwithstanding their racial denigration more generally. Yet struggles by different groups in the civil rights era to secure the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection under the law further illuminate the racial complexity of the South. Guadalupe San Miguel informs us that Mexican Americans in Houston, influenced by the Chicano Movement, declared that they were “Brown, not White,” after the school district in 1970 responded to a court desegregation order by placing whites in one school and African Americans and Mexican Americans—still classified as white—in another. Meanwhile, southern labor struggles have sometimes led African American workers to object to the competition from rapidly growing Latino and immigrant Southeast Asian, Caribbean, and Central American workforces in many southern manufacturing and food-processing plants. And, thus far, the success of politicians of Asian descent has been more likely than not to come at the expense of African American or Latino citizens. All of this suggests that racial lines may as easily be hardened as softened in a multiracial South. Far from auguring an inevitable break with the South’s racist legacy, therefore, the rupture of the biracial paradigm could simply presage new lines of color and newly separate communities. It remains, then, an open question whether the racial geography of this latest New South will look more like the formerly all-black neighborhood in east New Orleans that is now an amicably mixed community of African Americans and Vietnamese or more like the separate enclaves developing in other southern cities.

The ongoing demographic transformation of the 21st-century South suggests an ironic twist on Faulkner’s trenchant observation: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Much like the region itself, southern race relations were never as static, bounded, and monochrome as typically represented. From the start, a growing mixed-race population challenged fixed black-white boundaries, in law as well as in social relations. In southern households, slave masters, unable to master their own desires, produced claimants to their property and white privilege, fostering in the process a far more complex and contested racial landscape. In southern courtrooms, white-skinned slaves sued for their freedom, making hash of the notion that “race” was indelibly marked on the bodies or in the behavior of human beings. These claimants were not the last to make manifest the fact that race was something performed as well as seen. Julia Schiavone Camacho’s entry shows that the racial masquerades white-skinned slaves used to escape bondage were echoed in the hilarious send-up Chinese workers deployed to cross the U.S.-Mexican border in the early 20th century. Donning ponchos and sombreros and mumbling a few words of Spanish or singing traditional ballads, Chinese men passed themselves off as Indian or Mexican.

On the Mexican side of the border, these same Chinese created an even more complex racial identity, taking Mexican wives and fathering mixed-race children. As merchants and skilled tradesmen, they helped build their adopted nation’s economy, only to be victimized once again by anti-Chinese riots and pogroms during and following the Mexican Revolution. Consequently, they found themselves once again attempting to cross the border, but this time it was U.S. border officials who misrepresented their families’ racial identities—classifying them all as simply “Chinese” and sending them “back” to China.

Whether by disguise or misrecognition, therefore, race has been repeatedly revealed as ambiguous, with uncertain boundaries, constructed and reconstructed within the borderlands and contested spaces produced by the South’s social-historical transformation. Perversely, perhaps, the very ambiguity of race may be a source of its enduring power—for both those who impose and those who accept any given racial identity. Similarly, the blurring of the South’s geographic and demographic boundaries may mirror the blurring of its cultural origins. Its music, its cuisine, its architecture, all betray these diverse elements, all are deposits of this complex history. All this makes for a rich and complex past—and future.

THOMAS C. HOLT

University of Chicago

LAURIE B. GREEN

University of Texas at Austin

Fran Ansley and Jon Shefner, eds., Global Connections, Local Receptions: New Latino Immigration to the Southeastern United States (2009); Mark Bauman, ed., Dixie Diaspora: An Anthology of Southern Jewish Life (2006); Ira Berlin, American Historical Review (February 1980), Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (1998); Leslie Bow, “Partly Colored”: Asian Americans and Racial Anomaly in the Segregated South (2010); Jonathan Brennan, ed., When Brer Rabbit Meets Coyote: African–Native American Literature (2003); James F. Brooks, ed., Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America (2002); W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (2008); James C. Cobb and William Stueck, eds., Globalization and the American South (2005); Lucy M. Cohen, Chinese in the Post–Civil War South: A People without a History (1984); Stephanie Cole and Alison M. Parker, eds., Beyond Black and White: Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the U.S. South and Southwest (2004); Stephanie Cole and Natalie Ring, The Folly of Jim Crow: Rethinking the Segregated South (2012); Pete Daniel, Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Culture since 1880, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (2000); Allison Davis, Burleigh B. Gardner, and Mary R. Gardner, Deep South: A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class (1941); Jean Van Delinder, Struggles before Brown: Early Civil Rights Protests and Their Significance Today (2008); W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903); William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! (1936); Marcie Cohen Ferris and Mark Greenberg, eds., Jewish Roots in Southern Soil: A New History (2006); William Ferris, Give My Poor Heart Ease (2009); Barbara J. Fields, in Region, Race, and Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of C. Vann Woodward, ed. J. Morgan Kousser and James McPherson (1982); Neil Foley, Quest for Equality: The Failed Promise of Black-Brown Solidarity (2010), The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (1999); Jack D. Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples (1993); Laurie B. Green, Battling the Plantation Mentality: Memphis and the Black Freedom Struggle (2007); Michael D. Green, Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis (1982); Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, Troubling the Waters: Black-Jewish Relations in the American Century (2006); Ariela Julie Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (2008); James R. Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Black Migration (1989); Cindy Hahamovitch, No Man’s Land: Jamaican Guestworkers in America and the Global History of Deportable Labor (2011); Steven Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (2003); Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (1999); Paul Harvey, Freedom’s Coming: Religious Cultures and the Shaping of the South from the Civil War through the Civil Rights Era (2005); Thomas C. Holt, The Problem of Race in the Twenty-first Century (2002); Jacqueline Jones, Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War (2009); Winthrop Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550–1812 (1968); Moon-Ho Jung, Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation (2006); William Kandel and John Cromartie, New Patterns of Hispanic Settlement in Rural America (2004); Joseph Crespino and Matthew D. Lassiter, eds., The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism (2009); George Lewis, Massive Resistance: The White Response to the Civil Rights Movement (2006); James W. Loewen, The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White (1972); Neil R. McMillen, Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow (1989); Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in an Imagined South (2003); Jeffrey Melnick, Black-Jewish Relations on Trial: Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the New South (2000); Tiya Miles, Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (2005); Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop in the Age of Jim Crow (2010); David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 (1987); Mary E. Odem and Elaine Lacy, eds., Latino Immigrants and the Transformation of the U.S. South (2009); Susan Eva O’Donovan, Becoming Free in the Cotton South (2007); Theda Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540–1866 (1979); Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (2005); Kenneth W. Porter, The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People (1996); Hortense Powdermaker, After Freedom: A Cultural Study of the Deep South (1939); Albert J. Raboteau, Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans (1999); Susan Reverby, Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy (2009); James L. Roark, Masters without Slaves: Southern Planters in the Civil War and Reconstruction (1977); Joshua D. Rothman, Notorious in the Neighborhood: Sex and Families across the Color Line in Virginia, 1787–1861 (2003); Tony Russell, Blacks, Whites, and Blues (1970); Guadalupe San Miguel, Brown Not White: School Integration and the Chicano Movement in Houston (2005); Claudio Saunt, Black, White, and Indian: Race and the Unmaking of an American Family (2005); Rebecca J. Scott, Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery (2005); Rebecca J. Scott and Jean M. Hebrard, Freedom Papers: An Atlantic Odyssey in the Age of Emancipation (2012); Jim Sidbury, Becoming African in America: Race and Nation in the Early Black Atlantic (2007); Ronald T. Takaki, A Pro-slavery Crusade: The Agitation to Reopen the African Slave Trade (1971); Keith Wailoo, Dying in the City of the Blues: Sickle Cell Anemia and the Politics of Race and Health (2000); Clive Webb, Fight against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (2003); C. Vann Woodward, The Burden of Southern History (1993), The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1974).

Advertising (Early), African American Stereotypes in

At the 1893 Columbian Exhibition, at which Ida B. Wells protested African American exclusion, Aunt Jemima drew a warm welcome. A woman named Nancy Green, an ex-slave working as a domestic for a wealthy Chicago family, played the role. Outside a gigantic flour-barrel-shaped exhibition hall constructed by the milling company that had invented the pancake mix, Green’s Aunt Jemima served and sold pancakes to the fair’s overwhelmingly white visitors. Making the cakes might have been easy, but Green’s performance was complicated. Her character portrayed an advertising image that mimicked minstrel show performances inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s character Aunt Chloe, and yet it also drew from contemporary white southerners’ sentimental images of black antebellum “mammies.” Green was born into slavery, but Aunt Jemima was at least a copy of a copy (minstrel show “aunts”) of a copy (Aunt Chloe) of a white fantasy (the black mammy)—her connection to any real black woman lost in multiple layers of commercialized popular culture. Emancipation may have freed African American bodies, but popular culture made a great deal of profit selling black images. The tremendous popularity of Aunt Jemima in the late 19th century made clear the deep racial foundations of the increasingly national consumer market.

Advertising emerged as a national enterprise in the late 19th century in the midst of a minstrel show revival—the “coon song” craze—and white southerners’ sentimental Lost Cause fantasies of happy slaves. Most consumers were familiar with the standard minstrel characters: the uncles, aunties, and mammies; the “pickaninny,” or comic black child; the absurd black politician; the African “savage”; and the black figure trying and failing to live in the modern world.

Minstrelsy, a form of popular theater in which white men blacked up and cross-dressed to play black characters, originated in the antebellum Northeast in white working-class fantasies of black life in the South. In the postemancipation period, minstrelsy became extremely popular across the South, with its blacked-up characters acting out white southern fears and dreams of black life. As technological advances made the production of visual imagery increasingly affordable in the 1870s and 1880s, posters and playbills for minstrel acts papered small towns and cities and advertisements for minstrel shows and the sheet music for coon songs filled newspapers. Businesses quickly put these stylized images of black “types” to work selling other commodities. These racial representations, in turn, helped generate a new understanding of consumers as buyers detached from specific localities and from regional, ethnic, religious, and even, at times, gender and class identities—as buyers linked, in effect, to a larger, more abstract category through their whiteness: the national market.

The first advertisements to make extensive use of minstrel characters were trade cards, a new genre of advertising developed in the late 1870s and 1880s, which featured images and pitches for products on small pieces of card stock. Circulated by manufacturers, country stores, and urban shopkeepers, trade or ad cards appropriated demeaning images of not only African Americans but also American Indians and Asian Americans for the promotion of branded products and stores. Many early cards made no pretense of connecting the product and pitch to the visual imagery used to catch the attention of potential consumers. Often businesses chose cheaper stock images available from lithographers and printers. “Pluto,” a young black child wearing a hood and staring out of a background of flame with enlarged, whitened eyes, promoted both the Pomeroy Coal Company and McFerren, Shallcross, and Company Meats. Two black children tickling an old black man to sleep on a cotton bale appeared on cards for Trumby and Rehn furniture makers and for a photographer named Rabineau. Other images attempted to be more comic than sentimental. A Union Pacific Tea card used a minstrel show version of a black child’s face, ears, and lips, exaggerated and with eyes whitened, to illustrate four different emotional expressions.

The most popular racial images used on trade cards pictured black adults trying and failing to mimic their white “superiors.” Mismatched patterns and awkward clothes pairings suggested that blacks could never achieve that crucial marker of middle-class status, respectable attire. Often these outrageously dressed figures participated in elite leisure activities. On a card for Sunny South cigarettes in a scene labeled “Cape May,” a young black woman wearing clashingly striped clothes tries to play croquet. Her exaggerated mouth gapes in surprise and pain as she holds up her hurt foot. She has missed the ball and hit herself with the mallet instead. The ad invites middle-class and elite white consumers from across the nation to laugh at the black figure’s absurd attempt to enjoy the pastimes of a fashionable resort. A grinning, walleyed black man awkwardly rides a grinning, equally walleyed horse using a stiff saddle on a card for Vacuum harness oil. “People,” the pitch announces, “cannot exist without it,” effectively excluding this figure too ignorant to oil his tack from the category of humanity. In an explicit play upon whites’ fears of confusing appearances, a trade card for Tansill’s Punch, “America’s Finest Five Cent Cigar,” depicts a rear view of “Beauty on the Street.” Attired in respectable clothing, well corseted, and topped with a tasteful hat, the woman lifts her skirt and holds her parasol in one hand and her purse and a dog’s leash in the other. Flipping over the card reveals the joke. Beauty’s “Front View” reveals the woman’s face as black, coarse, and masculine. A whole category of cards made fun of wildly dressed black characters trying to use the telephone.

As advertising became more sophisticated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, cards appeared that specifically linked stylized black images to the ad copy. On a card for the St. Louis company Purina Mills, an “African” boy stands before a background of spindly palms and naked men. He wears the Purina breakfast box like a suit, and with a western spoon and dish in hand proclaims, “I Like the Best!” Purina almost makes him civilized. Other companies chose brand names that suggested blackness and allowed for an easy use of racial images in product pitches. “Nigger head” and “Niggerhead” became common product names for tobacco, canned fruits and vegetables, stove polish, teas, and oysters from around 1900 through the 1920s. Nigger-Hair Chewing Tobacco claimed to be as thick as black people’s hair. Trade cards promoted Korn Kinks cereal with pictures and stories of the adventures of the curly-headed little Kornelia Kinks. Still other companies chose brand names—Bixby’s Blacking, Bluing, and Ink and Diamond Dyes’ Fast Stocking Black—or wrote pitches that depended on the most visible marker of racial difference, skin color. On a card for Coates Black Thread, a white woman says to her servant, “Come in, Topsey, out of the rain. You’ll get wet.” “Oh!,” the servant replies, “it won’t hurt me, Missy. I’m like Coates Black Thread. Da Color won’t come off by wetting.”

In the late 19th century, black-figured items became profitable commodities themselves. Mammy and the “pickaninny” dolls, jolly-nigger banks, big-lipped and black-faced cookie jars and spoon rests, and other similar products flooded the market. An Aunt Jemima rag doll cost one trademark from the mix’s packaging plus five cents. The company bragged in its advertisements that “literally every city child owned one.” Not all white children could have a black servant, but all but the poorest could have their very own pancake mammies.

As magazine advertising expanded and incorporated visual imagery, it too made use of the minstrel-influenced images popular on trade cards. An 1895 Onyx Black Hosiery ad in the Ladies Home Journal depicted a crowd of pickaninnies with the caption “Onyx Blacks—We never change color.” Soap advertisements in particular used minstrel images and white racial fantasies to explain how their products worked rather than to simply attract attention. In the late 19th century, Kirkman’s Wonder Soap featured a mammy and two small boys to advertise its product. The mammy wears a head rag and stands over a washtub. One of her hands helps a naked black boy into the water on the right while her other hand holds a bar of white soap above a naked white boy getting out on the left. The copy describes “two little nigger boys” who hate to bathe. Only Kirkman’s soap was strong enough to perform miracles: “Sweet and clean her sons became—It’s true, as I’m a workman—And both are now completely white. Washed by this soap of Kirkman.”

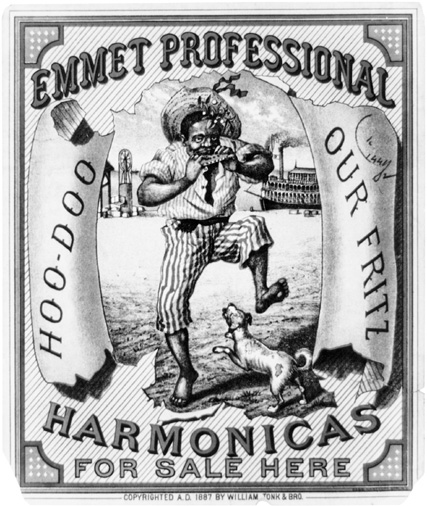

A stereotypical advertisement showing an African American man playing the harmonica, ca. 1887 (Library of Congress [LC-USZ62-87637], Washington, D.C.)

As advertising became more sophisticated in the early 20th century, “spokes-servant” ads became increasingly popular. These ads used and extended the theme of black racialized subservience, as branded characters like Aunt Jemima worked for the company and the company’s products worked for the consumer. In this way, these ads elided the service of the product with the service of the black figures promoting it. Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix magazine advertisements used this strategy and featured the mammy figure cooking her southern specialties, including pancakes, and serving up “Old South” hospitality everywhere she went. “I’se in town, honey,” she usually said, ready to serve white folks everywhere. The Gold Dust Twins, two pickaninny characters who promoted Gold Dust All Purpose Washing Powder and who were almost as famous as Aunt Jemima, appeared on a 1910 billboard. Foot-high letters announced: “Roosevelt Scoured Africa. The Gold Dust Twins Scour America.” The light within the image focused the consumer’s eye first on the towering and golden figure of Teddy Roosevelt, toward which an equally large and glowing figure of Uncle Sam in the left foreground reaches out a hand in honor. The smaller twins follow Roosevelt, carrying his bags, his gun, and a huge tiger carcass and playing the roles of housecleaning black servants and African porters. Gold Dust, through the twins, could do the work at home that Roosevelt had performed overseas.

In the 20th century, advertising perpetuated and extended the reach of minstrelsy’s black images, even as the traditional black-faced theatrical form increasingly survived as a form of popular theater. Aided by popular entertainment forms—vaudeville, radio, and later television—that it supported, advertising helped lodge minstrelsy’s racist fantasies deep within American popular culture.

GRACE ELIZABETH HALE

University of Virginia

Kenneth Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectables and American Stereotyping (1994); Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (1999); Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in an Imagined South (2003); Juliann Sivulka, Stronger Than Dirt: A Cultural History of Advertising Personal Hygiene in America, 1875–1940 (2001); Patricia A. Turner, Ceramic Uncles and Celluloid Mammies: Black Images and Their Influence on Culture (1994).

African American Landowners

Landownership gave African Americans a measure of economic security and greater independence from white control. Farm owners were their own bosses. They set their hours, controlled labor within their families, selected and marketed their own crops, and exerted a great deal of control over the education of their own children. Additionally, on their farms they were somewhat insulated from the humiliations of Jim Crow culture. Accordingly, from emancipation until the Great Migration, landownership was the goal most black families sought in order to fashion for themselves a meaningful freedom. After the federal government failed to supply Reconstruction-era blacks with the promised “40 acres and a mule,” they made significant progress on their own, despite widespread white hostility and prolonged agricultural depressions. By 1870, only 5 percent of all black families had achieved this goal; by 1910, a quarter of black southern families had done so.

Some African Americans became free and began purchasing land soon after they first arrived in North America as slaves in the early 1600s. But as the transatlantic slave trade brought increasing numbers of Africans into bondage, whites passed restrictive new laws to maintain them in a dependent position. As a result, the numbers of black farm owners grew very slowly. By the 19th century, two subregional patterns had evolved. Before the Civil War, few African Americans had obtained their freedom in the Deep South, but those who did frequently amassed property. While few in number, they constituted three-fourths of the South’s affluent free people of color (those who had more than $2,000 worth of property). They tended to be the descendants of whites, often receiving land and education through these family ties. They saw themselves as a separate “mulatto elite” and tended to identify with whites more than with blacks. This pattern was especially marked in Louisiana, where Spanish and French customs of interracial marriage and concubinage held sway.

Conversely, most free people of color lived in the Upper South, but few of these owned land before 1830. They had gained their freedom in a general wave of manumission that swept the region in the decades following the American Revolution. Most had not been related to their previous masters and did not derive long-term advantages from kinship ties with whites. Relatively few were literate or employed in skilled occupations. Those who did acquire land held only small parcels. Unlike African American landowners in the Deep South, those in the Upper South did not conceive of themselves as a separate “brown” society. Instead, they maintained social ties and intermarried with poorer blacks and slaves. Only 1 in 14 became slave owners, whereas fully a quarter of free people of color in the Deep South did so.

In the 1830s, regional patterns began to reverse. African American landowners in the Deep South lost ground, or at best merely held on as a group. At the same time, by their second generation after manumission, free people of color in the Upper South began to work their way into the skilled trades and professions and began to purchase land, matching the total property owned in the Deep South by 1860. When general emancipation came, they accelerated this trend. Although their holdings were usually modest in size, they made extraordinary progress.

African American farm ownership peaked from 1910 to 1920 at one-quarter of black farm families. This achievement was far from evenly distributed, as 44 percent of farmers in the Upper South came to own land, whereas only 19 percent did so in the Deep South. Generally, the sparser African American population was in a state, the easier a path black farmers found to landownership. In Georgia, only 13 percent of black farmers owned their own land; in Alabama and Mississippi, 15 percent; in Louisiana, 19 percent; in South Carolina, 21 percent; in Arkansas, 23 percent; in Tennessee, 28 percent; in Texas, 30 percent; in North Carolina, 32 percent; in Florida, 50 percent; in Kentucky, 51 percent; and in Virginia, 67 percent.

Many of these black farm owners were scattered and isolated among white farmers. But in many places, such as Texas and Mississippi, they settled in freedom colonies—all-black communities that provided most of the basic needs of their members. In these settlements, they frequently had their own churches, schools, lodges, and businesses. Although they did not farm on a large scale, with aid from black county extension agents they raised enough of their own food to avoid debt. Their relative economic independence gave them greater control over their lives than that enjoyed by black tenants. For example, when civil rights workers registered rural African Americans to vote during the 1960s, they frequently stayed in the homes of black farm owners.

Black farm owners have declined in number continuously from the 1920s to the present. Many lost their land owing to the general difficulties afflicting small farmers: the boll weevil and the lower prices and higher costs brought by an industrializing, globalizing economy. Other families sold their land when their young people began to identify farming with the exploitation of slavery and sharecropping and turned increasingly away from their parents’ farms and toward urban occupations. Still others lost their farms because of the liabilities of racism, in particular, difficulty in gaining equitable aid from banks and government agencies. For many decades, local administrators of USDA farm loan agencies denied loans to African American farmers, while giving them to comparable white farmers. In other cases, these agencies extended loans that were too small or too late to be useful. To seek compensation for this pattern of discrimination, thousands of black farmers brought a class-action lawsuit against the USDA, in Pigford v. Glickman. In 1999, a Washington, D.C., district court found for the plaintiffs and called for damages to be paid, which have amounted to nearly 1 billion dollars, the largest class-action civil rights settlement in U.S. history. Suit brought by an additional 60,000 late filers may bring the full settlement to over 2 billion dollars.

MARK SCHULTZ

Lewis University

W. E. B. Du Bois, U.S. Department of Labor Bulletin (July 1901); Melvin Patrick Ely, Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (2005); Peggy G. Hargis and Mark R. Schultz, Agricultural History (Spring 1998); Leo McGee and Robert Boone, The Black Rural Landowner: Endangered Species (1979); Gary B. Mills, The Forgotten People: Cane River’s Creoles of Color (1977); Debra Reid, Reaping a Greater Harvest: African Americans, the Extension Service, and Rural Reform in Jim Crow Texas (2007); Debra Reid and Evan Bennett, eds., Beyond Forty Acres and a Mule: African American Farmers since Reconstruction (2012); Loren Schweninger, Black Property Owners in the South, 1790–1915 (1990); Thad Sitton and James H. Conrad, Freedom Colonies: Independent Black Texans in the Time of Jim Crow (2005).

African Influences

In 1935, Melville J. Herskovits asked in the pages of the New Republic, “What has Africa given America?” In his answer, a radical response for the time, he briefly mentioned the influence of blacks on American music, language, manners, and foodways. He found most of his examples, however, in the South. Eighty years later, the answer to this question could be longer, perhaps less radical, but still surprising to many. Much of what people of African descent brought to the United States since 1619 has become so familiar to the general population, particularly in the South, that the black origins of specific customs and forms of expression have become blurred or forgotten altogether.

Consider, for example, the banjo. Not only is the instrument itself of African origin but so is its name. Although the banjo is encountered today chiefly in bluegrass ensembles, where it is considered an instrument of the Appalachians, it was first played by slaves on Tidewater plantations in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was only taken up into the Piedmont and the mountains during the 19th century by blacks working on railroad gangs. Although the contemporary banjo is physically quite different from its Afro-American folk antecedent, it nonetheless retains the unique sounds of its ringing high drone string and its drum head. These are the acoustic reminders of the instrument’s African origins.

Linguists have noted that southern speech carries a remarkable load of African vocabulary. This assertion is all the more remarkable when we recall that white southerners have often claimed to have little interaction with blacks. Some regional words have murky origins, but there is no controversy for such terms as boogie, gumbo, tote, benne, goober, cooter, okra, jazz, mumbo-jumbo, hoodoo, mojo, cush, and the affirmative and negative expressions “uh-huh” and “unh-uh.” All are traceable to African languages and usages. The term “guinea” is used as an adjective for a number of plants and animals that were imported long ago from Africa. Guinea hens, guinea worms, guinea grass, and guinea corn, now found throughout the South, are rarely thought of as exceptional, even though their names directly indicate their exotic African origins.

Beyond basic words, blacks have created works of oral literature that have become favorite elements of southern folklore. Within the whole cycle of folktales with animal tricksters—those put into written form by Joel Chandler Harris and others—some may be indigenous to American Indians and some may have European analogies, but most appear to have entered the United States from Africa and the West Indies. The warnings they provide concerning the need for clever judgment and social solidarity are lessons taken to heart by both whites and blacks. The legacy of artful language in Afro-American culture is manifested further in other types of performance such as the sermon, the toast, and contests of ritual insult. For people who are denied social and economic power, verbal power provides important compensation. This is why men of words in the black community—the good talkers—are highly esteemed. The southern oratorical style has generally been noted as distinctive because of its pacing, imagery, and the demeanor of the speaker. Some of these traits, heard in speeches and sermons, are owed to black men of words who of necessity refined much of what is today accepted as standard southern “speechifying” into a very dramatic practice.

In the area of material culture, blacks were long assumed to have made few contributions to southern life, but such an assessment is certainly in error. There have, over the last four centuries, existed distinctive traditions for Afro-American basketry, pottery, quilting, blacksmithing, boatbuilding, woodcarving, carpentry, and graveyard decoration. These achievements have gone unrecognized and unacknowledged. Take, for example, the shotgun house. Several million of these structures can be found all across the South, and some are now lived in by whites, although shotgun houses are generally associated with black neighborhoods. The first of these distinctive houses with their narrow shapes and gable entrances were built in New Orleans at the beginning of the 19th century by free people of color who were escaping the political revolution in Haiti. In the Caribbean, such houses are used in both towns and the countryside; they were once used as slave quarters. Given its history, the design of the shotgun house should be understood as somewhat determined by African architectural concepts as well as Caribbean Indian and French colonial influences. Contemporary southern shotgun houses represent the last phase of an architectural evolution initiated in Africa and modified in the West Indies and now in many southern locales dominating the cultural landscape.

The cultural expressions of the southern black population are integral to the regional experience. Although the South could still exist without banjos, Brer Rabbit, goobers, and shotgun houses, it would certainly be less interesting. The black elements of southern culture make the region more distinctive.

JOHN MICHAEL VLACH

George Washington University

J. L. Dillard, Black English (1972); Dena J. Epstein, Ethnomusicology (September 1975); Melville J. Herskovits, New Republic, 4 September 1935; Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (1983); John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (1978), Pioneer America (January 1976).

Agriculture, Race, and Transnational Labor

The plantation economy that dominated the American South through the colonial and early national periods sharply defined labor and race relations in the region. Millions of African and African American slaves toiled in the tobacco, cotton, sugar, and rice fields, fueling a highly profitable cash crop economy dependent on the subjugation of their labor. The powerful labor system upon which the plantation economy was built collapsed with the advent of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Soon after, southern planters, hoping to rebuild their political and financial power, complained about the unreliability and inefficiency of newly freed black labor. Despite planters’ efforts to stabilize and immobilize black farmworkers through a system of farm tenancy, many African Americans searched for better opportunities through migration.

As the southern agricultural economy transformed in the late 19th century, the concern over a steady labor supply became more serious. America’s Industrial Revolution fostered new urban markets with growing populations requiring food and factories demanding raw materials. The development of refrigerated railway cars and the application of new machinery to agricultural production further incentivized the expansion of large-scale, capitalized farms in the South. With increasing numbers of African Americans leaving in search of better economic opportunities and social conditions, planters were left to search for alternatives to meet their growing labor needs. The Great Migration resulted in an exodus of about 500,000 black southerners between 1910 and 1920 alone. To meet these needs, planters relied increasingly on seasonal migrants, who could provide flexible and inexpensive labor.

Texas had long depended on the transnational migration of Mexican farmworkers, who after 1910 (the start of the Mexican Revolution) began arriving in greater numbers. During the same decade that black southerners left the countryside at growing rates, more than 185,000 Mexicans entered the United States in search of work. The availability of Mexican laborers facilitated Texas’s transformation from a plantation and ranching economy into commercial agribusiness. Between 1900 and 1920, the number of cultivated acres on Texas farms grew from 15 million to 25 million. By this time, central Texas was the nation’s leading cotton-producing region and south Texas was dominant in the truck farming of vegetables and citrus fruit. The system of agribusiness based on inexpensive, migrant, and mostly noncitizen labor that existed in Texas by World War I would soon spread across the South, pushing the region to follow a new model of farm labor relations.

While the presence of a large transnational labor force distinguished Texas from the rest of the American South in the early 20th century, other regions experimented with the use of immigrant labor following the Civil War. Several states sought to use immigration to revive agribusiness and resolve enduring political tensions. A study of South Carolina during Reconstruction shows that there was much discussion on the question of transnational labor. According to historian R. H. Woody, state leaders believed that “the West had been made powerful and prosperous through immigration, and this same factor would increase the wealth and property values of South Carolina.” Labor recruiters were sent to Germany and the Scandinavian countries to lure workers to the New South. Some South Carolinians warned that “a day laborer could not compete with the Negro in the service of the former slave-owner, or in the cultivation of southern staples.” To a large extent, such skeptics were right. Most of the immigrants who came to the region during the late 19th century complained about the poor climate, disorderly society, and lack of real economic opportunities.

Louisiana had more success employing immigrant farmworkers at the turn of the century. At this time, most of the sugar cultivated in the continental United States grew in the southeast and south-central areas of Louisiana. After the 1880s, Italian immigrants were recruited as replacements for low-wage, mostly unskilled black labor. The seasonal influx of Italian workers ranged from 30,000 to 80,000. Most came from established enclaves in New Orleans that worked around the citrus fruit trade, while others migrated from Chicago and New York. Like most states seeking an immigrant workforce, Louisiana established immigration and homestead associations to encourage Italian immigration. Soon after, a successful transnational system was in place, with workers arriving directly to the cane fields at grinding time and returning to Italy immediately after. This cyclical pattern allowed Louisiana’s sugar parishes to thrive. It was not until economic depression hit the sugar industry in the early 1900s that Italians left the sugar fields searching for better wages. During World War I and shortly after, restrictive federal immigration policies also served to limit Italian immigration.

The Reconstruction period also saw the arrival of Chinese labor to the Mississippi Delta. In 1869, southern growers organized the Arkansas River Valley Emigration Company, whose purpose it was to attract large numbers of Chinese laborers for the cultivation of cotton. According to historian John Thornell, labor recruiters were sent to Hong Kong in search of willing migrants, and eventually two ships arrived in New Orleans in 1870 with about 400 Chinese workers. Members of this group arrived in the Delta to work specifically in agriculture. Like their Italian counterparts, they considered themselves sojourners, expecting to return to their homeland once they had secured enough money to support their families. While their expectations were hopeful, their experiences as farmworkers were mostly unsuccessful. Exploitative labor conditions on cotton farms, which included terribly low wages for extremely physically demanding work, encouraged most Chinese migrants to reconsider their arrangements. Those that did not return to China walked off the farms to find better opportunities. Many became small business owners and opened grocery stores that catered to black farmworkers. The Chinese immigrant community could have flourished had it not been for the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

Mexican migrants began arriving in the Mississippi Delta shortly after growers experimented with hiring Chinese workers. As historian Julie Weise explains, Mexicans were working in the state’s lumber industry as early as 1908 as replacements for black workers who left for cities in the North and West as part of the Great Migration. During the period from 1917 to 1921, a federal guest-worker program attracted some 51,000 Mexicans to help meet World War I labor demands, mainly in agriculture. Most of the migrants who arrived in Mississippi came from north-central Mexico and were recruited at the Texas border by labor agents working for southern cotton growers. By the mid-1920s, Mexican workers realized that they could earn more picking cotton in the American South than elsewhere in the country, including Texas and California. In 1925, a peak period in the migratory flow, some 500,000 Mexicans could be found picking cotton throughout the region. Not all of the Mexican workers were transnational migrants, however. A 1930 census figure taken in the Delta’s Bolivar County revealed that one in every six Mexican farmworkers had actually been born in Texas. Few Mexican farmworkers stayed in the Delta after December, when the cotton-picking season ended. Most chose to follow the migratory route back to Texas, up north, or to Mexico.

The impermanent character of the transnational labor that came to the South after the Civil War allowed southerners to avoid altering the racial division of labor that existed in the region. Southern planters simply tried to replace African American slaves (or newly empowered black workers) with an alternative source of exploited labor to sustain productivity on their farms. In the 1930s, for example, the use of Mexican labor in the Delta would serve to undermine the solidarity black workers were building through the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. In this way, the use of transnational labor was not just a response to black out-migration but also a means to undermine domestic workers’ coalitions.

Despite their diverse origins, the Italian, Chinese, Mexican, and even German immigrants that first came to the South as farmworkers were inserted (often uncomfortably) into the existing black-white racial dyad. Their labor status alongside low-wage African American workers—at times also cohabitating, intermarrying, and organizing with blacks—tainted these migrants racially in the eyes of white society. Those that actively sought acceptance as whites by attending white schools and churches, challenging segregation in court, or elevating their class status, encountered significant barriers in transgressing the color line. For Mexican migrants, according to Weise, it was the actions of the Mexican Consulate that eventually helped them gain some of the privileges of whiteness.

The influx of immigrant labor to the South slowed during much of the mid-1920s and 1930s as the nation experienced a severe economic depression that fueled nativist sentiment and policies. It was not until the 1940s, with mounting World War II labor demands, that growers again clamored for a transnational farmworker program. The Bracero program consisted of a series of bilateral agreements between the U.S. and Mexican governments that lasted from 1942 to 1964. Over the duration of the program, more than 4.5 million Mexican farmworkers were contracted (often more than once) to work in the United States. In negotiations over the stipulations of the agreement, the Mexican government addressed the problem of racial discrimination many of its nationals experienced as U.S. workers. Several states, including Texas, Arkansas, and Mississippi, were blacklisted from participating in the program until they could guarantee better labor and living conditions, including an end to the racial prejudice Mexicans encountered.

The British West Indies Labor Program was modeled after the Mexican agreement to meet farm labor demands on the East Coast. Approximately 66,000 workers, mostly from Jamaica and the Bahamas, participated in the program from 1943 to 1947. According to historian Cindy Hahamovitch, the secretary of state for the British colonies attempted, much like Mexican officials, to regulate the discriminatory conditions workers encountered by discouraging migrants from working south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Even so, Florida growers were determined to secure guest workers and ultimately received some of the largest numbers.

The cycles of migration created by such guest-worker programs had a long-lasting affect in establishing a more permanent and visible presence of migrants in the South. Since the 1960s, particularly as African Americans gained access to industrial and service-sector jobs, the regional workforce has undergone what many describe as a “steady process of Latinization.” Caribbean guest workers continue to migrate under the H-2A temporary worker program, but the rate of employment among Latino farmworkers far outnumbers any other group. Unlike past migrations, Mexican (and to a lesser extent Central American) immigrants have been arriving in the South and then settling. Since 1990, eight out of the top ten “states with fastest growing nonmetro Hispanic populations,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, are located in the American South.

As Latino immigrants settle in the South, local communities are faced with the challenge of integrating them beyond their roles as migratory workers. This adjustment has led to anti-immigrant hostility and the escalation of racial tension. Recently, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina passed anti-immigrant legislation under the guise of protecting Americans’ jobs. A notable concern among nativists has also been the dilution of southern culture and values, resembling the immigration debates that occurred shortly after the Civil War. Growers generally do not support such legislation, knowing that it will undermine the current system, which provides them with cheap and vulnerable workers. Immigrant farmworkers are organizing in remarkable ways to contest the structural violence and exploitative conditions that too closely resemble the postbellum era. For example, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, an organization of mainly Latino, Mayan Indian, and Haitian immigrants, offers a source of promise that the existing system of agribusiness can be reformed for the better. Over time, transnational workers have disrupted the traditional structure of labor and race relations, forging a new American South.

VERÓNICA MARTÍNEZ MATSUDA

Cornell University

Neil Foley, The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (1997); Cindy Hahamovitch, The Fruits of Their Labor: Atlantic Coast Farmworkers and the Making of Migrant Poverty, 1870–1945 (1997); William Kandel and John Cromartie, New Patterns of Hispanic Settlement in Rural America (2004); James W. Loewen, The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White (1971); Mary E. Odem and Elaine Lacy, eds., Latino Immigrants and the Transformation of the U.S. South (2009); Vincenza Scarpaci, Italian Immigrants in Louisiana’s Sugar Parishes: Recruitment, Labor Conditions, and Community Relations, 1880–1910 (1980); John Thornell, Chinese America: History and Perspectives (2003); Julie M. Weise, American Quarterly (September 2008); R. H. Woody, Mississippi Valley Historical Review (September 1931).

Asian American Narratives between Black and White

How did Jim Crow culture view Asian Americans, those who did not fit into a system predicated on the distinction between “colored” and white? Asian American narratives about racial segregation in the South reveal more than one answer to the question where did the Asian sit on the segregated bus? In doing so, they offer important insights into the ways in which racial hierarchies were enforced in southern culture.

Interned with other Japanese Americans in Arkansas during World War II, Mary Tsukamoto recounts that her first trip out of camp, a bus ride to Jackson, Miss., in 1943, offered a shocking view of racial discrimination: “We could not believe the bus driver’s tone of voice as he ordered black passengers to stand at the back of the bus.” In contrast, the white driver gestured her to the front. “We were relieved but had strange feelings,” she writes. “Apparently we were not ‘colored.’”

Tsukamoto’s dilemma—front or back?—goes largely unnoticed in depictions of segregation-era history. The fact that Mary is designated “not ‘colored’” here belies the fact that she is also a victim of racial discrimination: she is a prisoner of war on temporary furlough from the “segregation” of a concentration camp. The story reveals complex issues surrounding the indeterminate racial status of Asian Americans between black and white. In 1930, sociologist Max Handman noted that American society had “no social technique for handling partly colored races.” As a metaphor, the “color line” does not allow for a middle space. One Chinese American woman living in Mississippi stated, “Delta whites think there are only two races in the world and do not know what to do with the Chinese.” Similarly, the Korean protagonist of Susan Choi’s novel The Foreign Student, set in Sewanee, Tenn., in the 1950s, reflects upon the locals’ reaction to him: “They don’t know what to make me.” The Asian’s racial status became subject to interpretation.

Asian Americans have often been positioned in American culture as vehicles for affirming racial progress; they are continually represented as the “model minority,” as proof that systemic racial barriers do not exist. Yet segregation affected Asians in the South as well as African Americans; while neither white nor black, they were not immune to the racial hierarchies enforced in southern culture. Asian American novels, ethnographies, oral histories, and memoirs about the South provide intriguing accounts of the ways in which interstitial individuals became written into the region’s prevailing racial codes. These narratives reveal what it means to inhabit an in-between space, what it means to be, in Handman’s words, “partly colored.” While this emerging body of letters contributes to a reevaluation of the transnational aspects of southern literature by highlighting global migration to the South, Asian American literature here, like African American literature, also testifies to the effects of white supremacy, offering a powerful—if at times ambiguous—critique of social injustice.

Some accounts of Asian American experiences with segregation and its legacy simultaneously document unjust racial treatment and, curiously, deny unjust treatment. Reflecting on his fieldwork in Georgia and Tennessee in the 1960s, Korean anthropologist Choong Soon Kim poses the question “Had a proverbial ‘southern hospitality’ been extended to Asians?” Throughout his ethnographic writing, Kim affirms that it has. In An Asian Anthropologist in the South: Field Experiences with Blacks, Indians, and Whites, he assures his readers that despite witnessing racial discrimination against African Americans, he himself does not experience it while living in the South. Yet he also confesses that white people have, upon occasion, refused to shake his hand. Kim writes, “These incidents should not be interpreted in terms of racial discrimination. Such curiosities in relation to foreigners are rather natural.” Kim’s analysis of his own treatment points to the unreliability of autobiographical narratives: He has been snubbed because of his race but dismisses the discourtesy and its implications. His contradictory testimony unveils the ways in which individuals rationalize a loss of social status, highlighting the psychic violence that is part of segregation’s legacy. The Asian American’s depiction of racial hierarchy requires reading in-between the lines of the narrative.

Segregation-era oral histories and memoirs reveal that individuals will resist the implication that they are inferior because of their race or skin color. For example, Ved Mehta’s account of his 1950s residence at a school for the blind in Arkansas reveals very little about what it means to be South Asian in a “whites only” institution. Rather, his memoir, Sound-Shadows of the New World (1985), asks us to consider another form of integration—the mobility of the blind in a sighted world. In spite of the fact that Mehta has deliberately downplayed his Indian cultural difference at school, he is moved out of the boys’ dormitory and into a converted broom closet. The move is represented as an administrative concession to Ved, a privilege granted to him alone. As the white director suggests, “You want a place where you can shut the door and be by yourself, keep on with your typing and reading, listen to Indian music and think of home. Am I right?” Whether he understands this separation to be anything other than voluntary goes unremarked. Why is Mehta singled out for “special” treatment? Does the separation represent a concession to time and place, one whose motive remains veiled even to the author?

An Asian in the South, Mehta is, in Handman’s terms, only “partly colored”: The move within the white school away from white boys may be interpreted either as a privilege or in deference to segregation. As in contradictory anecdotal evidence of Asians traveling in the South, he is not quite white. What is telling is that Mehta refuses to allow southern norms to impact his own self-conception, preferring to see himself as simply a brown-skinned human being whose worth remains intact. In his eyes, he is not a “darky,” not a “Negro.” Asian American literature nevertheless reveals that the entrenched customs of the South implicate these migrants, Kim and Mehta, even as they themselves are only partially aware of it. If these memoirs refuse to document the effects of racism in overt ways, they nevertheless contribute to an understanding of southern race relations by testifying to the individual’s attempts to resist racism’s dehumanizing effects.

As in the most popular depiction of Asians in the South, Mira Nair’s 1991 film, Mississippi Masala, Asian American literature denormalizes racial separation in the United States through global parallels. For example, Susan Choi’s novel The Foreign Student (1998) offers a meditation on the artificiality of divisions in its dual settings: Korea and Tennessee in the 1950s. The demilitarized zone at the 38th parallel, the imaginary line that divided the Korean peninsula into north and south as a result of civil war, finds its analog in the Mason-Dixon Line. The novel’s Korean protagonist, Chang, comes to occupy a racial DMZ, finding himself “foreign” to American racial politics at the University of the South.

The novel thus highlights a dynamic reflected in anecdotal accounts of Asian experiences with segregation: the Asian American becomes an object of intense local scrutiny and interpretation, particularly as Chang begins a relationship with a white woman. Choi describes reaction to the interracial couple as “unremitting scrutiny, disguised as politeness,” and as the “tension of careful indifference . . . and steady observation.” There is no communally agreed-upon response to the Asian’s unwitting crossing of the color line’s sexual taboo—because he is not black, their outings avoid overt hostility and confrontation, but because he is not white, surveillance is uncensored and undisguised. The novel establishes a tone of impending menace reflective of author David Mura’s speculation about Japanese Americans interned in Arkansas: “There was an unspoken message all about them in the camps, especially in the South: Things are bad now, but they could be worse. We aren’t lynching your kind. Yet.” The gray zone of Jim Crow culture that the Asian inhabits is depicted as both similar to and distinct from that experienced by African Americans; the novel intimates that suspended evaluation and punitive action are contingent upon unspoken rules.

Abraham Verghese’s My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story of a Town and Its People in the Age of AIDS also represents an Asian American’s search for home in the South. Like Choi’s work, it calls upon the condition of postcolonial exile to comment on segregation—here based not only on racial division but also on lines drawn between illness and health. An immigrant of South Asian ancestry, Verghese is an infectious disease specialist who was treating individuals infected with HIV in rural Tennessee in the mid-1980s. In defiance of southern stereotyping, the doctor was readily embraced by the white population as a fellow “good ole boy.” Yet as his practice with AIDS patients grows and he encounters increasing ostracism in the community, Verghese experiences his pariah status as racial alienation: “Was there some place in this country where I could walk around anonymously, where I could blend in completely with a community, be undistinguished by appearance, accent or speech?” The doctor’s own difference becomes “outed” via proximity to the presumed medical and sexual deviances of those he treats, linking the memoir’s representation of race to sexuality.

My Own Country’s significance to southern literature lies in its highlighting alternative forms of caste making in ways that complicate community division based on race. In doing so, it also refigures lines of connection away from the identity categories that have traditionally configured southern communities. The Asian American finds a contingent home in the South by forging meaningful connections with other “migrants,” in this case, white gay men who have returned home to Tennessee. The literature shows that being an outsider can provoke new forms of community.

The addition of Asian American writing to the southern canon does not simply contribute uncritically to notions of a multicultural New South. It can expand the global reach of regionalism by provoking questions about citizenship, diaspora, migration, acculturation, and transnationalism. But as significant, these narratives offer a potentially reorienting perspective on the dynamics at the heart of southern literature: racial politics between black and white. In this sense, authors such as H. T. Tsiang, V. S. Naipaul, Cynthia Kadohata, Lan Cao, Elena Tajima Creef, Patsy Rekdal, Abraham Verghese, Ved Mehta, Patti Duncan, Ha Jin, Susan Choi, Choong Soon Kim, and M. Evelina Galang who set prose narratives in the region are not “foreign” to southern letters. They too offer a critique of American racial politics, forcing a reconsideration of what it means to be “at home” in the South. The impact of white supremacy on Asian Americans might lack the immediacy of James Baldwin’s recognition that, as a black man, he is “among a people whose culture controls me, has even, in a sense, created me.” Nevertheless, southern Asian American literature offers insight into the complexities of social power, belonging, and denial.

Asian American narratives ask us to consider the arbitrary division between blacks and whites from the perspective of those whose place across the color line was indeterminate and often fluid. These postsegregation-era texts establish the interstitial as a site of cultural discipline, but they also give it an alternative political valence. The anomaly of the Asian in the South might be reconceived as a useful site of alienation from entrenched race relations, an estrangement that provides the space for questioning norms of racial etiquette, habit, and expectation. In this sense, the racial in-between pushes us to think beyond the lines drawn by color that constitute segregation’s ongoing legacy.

LESLIE BOW

University of Wisconsin at Madison

Brewton Berry, Almost White (1963); Edna Bonacich, American Sociological Review (October 1973); Leslie Bow, “Partly Colored”: Asian Americans and Racial Anomaly in the Segregated South (2010); Lan Cao, Monkey Bridge (1997); Susan Choi, The Foreign Student (1998); Lucy M. Cohen, Chinese in the Post–Civil War South: A People without a History (1984); Elena Tajima Creef, North Carolina Literary Review (2005); Max Sylvius Handman, American Journal of Sociology (1930); Cynthia Kadohata, kira-kira (2004); Choong Soon Kim, An Asian Anthropologist in the South: Field Experiences with Blacks, Indians, and Whites (1977), in Cultural Diversity in the U.S. South: Anthropological Contributions to a Region in Transition, ed. Carole E. Hill and Patricia D. Beaver (1998); James W. Loewen, The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White (1972); Ved Mehta, Sound-Shadows of the New World (1985); David Mura, in Under Western Eyes: Personal Essays from Asian America, ed. Garrett Hungo (1995); V. S. Naipaul, A Turn in the South (1989); Robert Seto Quan, Lotus among the Magnolias: The Mississippi Chinese (1982); Mary Tsukamoto and Elizabeth Pinkerton, We the People: A Story of Internment in America (1987); Abraham Verghese, My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story of a Town and Its People in the Age of AIDS (1994).

Asians, Mexicans, Interracialism, and Racial Ambiguities

Although Chinese men first arrived in the Spanish borderlands during the 16th century, they began arriving in northern Mexico in greater numbers after formal exclusion from the United States in 1882. Owing to gender norms in China and gendered exclusionary policy in the United States, Chinese migrations to the Americas were overwhelmingly male. Some men, intent on crossing the northern border surreptitiously, simply passed through Mexico. Others found opportunities in the burgeoning border economy and settled in local communities. Becoming both laborers and businessmen, Chinese in the latter group in particular formed romantic unions with local women. Anti-Chinese campaigns that emerged during the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and peaked with the Great Depression targeted Mexican-Chinese unions as damaging to the Mexican race and nation. Ultimately, the northwestern states of Sonora and Sinaloa drove out the vast majority of Chinese. Whether by choice or by force, their Mexican-origin families often accompanied them out of Mexico. Some passed through U.S. territory as “refugees” before beginning their lives anew in Guangdong Province in southeastern China.