Music, Recordings

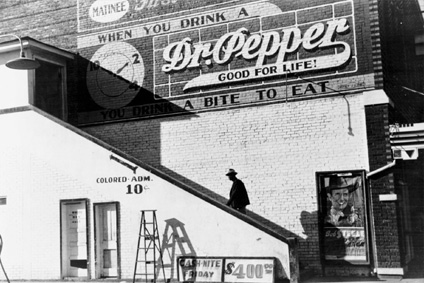

Blues and country, jazz and pop, hip-hop and indie rock: it is difficult to talk about the history, the sound, and the meaning of southern music without invoking racial categories. It can appear as if the region is home to separate black and white musical traditions, reaching back across the Atlantic to Europe and Africa and continuing through the contemporary country and R&B charts. Forays across the musical color line—from Elvis’s boogie and Stevie Ray Vaughan’s blues to the country music of black artists such as Ray Charles and Charlie Pride—can appear transgressive, the exceptions that prove the rule of historical relationship between music and race in the South. Far from indelible, however, the racial music categories of the 20th century can largely be traced back to the twin emergence of southern segregation and the phonograph industry.

Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in the year of the Compromise of 1877. The commercial market for musical recordings matured alongside white southerners’ development of a legal system of racial segregation. The commercial recording industry maintained a complex relationship with Jim Crow segregation, which echoed throughout the 20th century and beyond.

Some music had developed racial connotations before the advent of sound recording, of course. People of African descent in slavery and freedom had used music—from the spirituals and the ring shout to field hollers and the additive rhythms of Congo Square in New Orleans—to forge a collective identity, to signify a common history, or to express a shared condition. White southerners likewise used music—including European-derived art music and, beginning in the 1830s, blackface minstrelsy—to express an ever-changing white identity. Yet black and white southerners never limited themselves to making or enjoying music that expressed their own racial identities, no matter how important and vibrant those traditions were. Southerners partook of the vast array of music available to them, and they did so for a variety of reasons, including to express themselves, to imagine themselves part of a larger, perhaps better world, or simply to feel pleasure. Southerners’ musical lives were never constrained by the racial categories that have come to represent them.

The advent and spread of phonograph recordings changed the ways in which many understood the relationship between music and race. Records enabled the separation of music from musicians. Disembodied sounds floated free from their source. Ultimately, this separation led many commentators and consumers to ascribe racial and regional identities to sounds themselves rather than to the people who made them. In the early years of the phonograph business, a time when black performers largely were barred from recording, this division facilitated a thriving market for white performers’ renditions of what they claimed to be “Negro” music. The industry promoted minstrel ditties, spirituals, and blues recorded by white singers as genuine black music. Black artists successfully challenged industry segregation and minstrelsy in the 1920s by insisting on the correspondence between racial sounds and racial bodies. Black music was made best by black people.

The resulting “race records” market was a boon to African American artists and consumers. For the first time, music by black Americans was widely commercially available on record. At the same time, however, the new configuration reversed previous conceptions of the relationship between race and music. Phonograph companies insisted that African American performers only record what the industry considered to be black music. This resulted in wonderful and important blues and jazz recordings, but black artists often were barred from recording other parts of their repertoires, such as pop songs, Broadway hits, classical selections, or folk songs. A similar process occurred with the marketing of white southern recording artists. Long engaged with the wide variety of music echoing through the nation, they were marketed as “hillbilly” or “old-time” singers.

The segregated marketing of “race” and “hillbilly” music did little to represent the vibrant, complex, interregional everyday world of southern music. It did, however, correspond to the new concepts of racial distance and separation that white citizens were promoting in the Jim Crow South. It also provided the template for categorizing and marketing southern music according to race for the rest of the 20th century.

KARL HAGSTROM MILLER

University of Texas at Austin

Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop in the Age of Jim Crow (2010); Tony Russell, Blacks, Whites, and Blues (1970); Elijah Wald, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (2004).

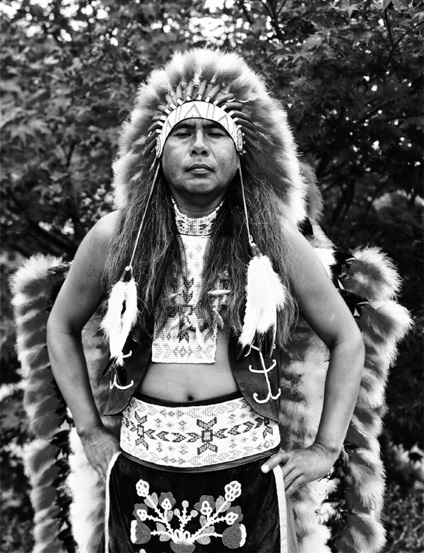

Native American Removal, 1800–1840

When the invention of the cotton gin made upland cotton a viable cash crop for thousands of Upcountry settlers, Georgia and the territory that became the states of Mississippi and Alabama were home to 32,800 first people, 53,400 free people, and 30,000 enslaved people. By 1840, when the first postremoval censuses were taken, the same region was home to 922,000 free people and 737,000 enslaved people. Census takers failed to note any remaining Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws because nearly all of them had been expelled from the region during the previous decade.

Why would state and federal governments forcibly expel people whose ancestors had inhabited the land for millennia? President Andrew Jackson had advocated removal since his days as the commander of the Tennessee militia in the Creek Civil War and cited the threat that so-called Indians posed to settler society as well as the incompatibility of the two cultures. Rather than await what everyone expected to be their inevitable extinction, Jackson believed that the federal government had to remove the indigenous people to the West where they could perpetuate their “race.” Despite considerable opposition to the proposal in both houses, Jackson garnered enough congressional support to see the measure pass, and he signed the Indian Removal Act on 29 May 1830.

Choctaws were the first to experience removal under the auspices of the Indian Removal Act, and subsequent treaties with the Creeks in 1832, the Chickasaws in 1834, and the Cherokees in 1835 secured the removal of those nations and the cession of their land. All told, the federal and state governments expelled just more than 50,000 people from their homelands, some in chains, others at gunpoint, and acquired almost 30 million acres of land for settlement, taxation, and development. In the ongoing construction of a society whose citizens saw the world in terms of white freedom and black slavery, there was simply no place for “Indians.”

The federal government kept no systematic records of the removals, so it is difficult to ascertain how many people died. Perhaps a third of removed Choctaws perished, while the tally of 4,000 Cherokee deaths on the Trail of Tears, one quarter of the total number of Cherokees removed, is a likely estimate. Perhaps 10,000 Cherokees who would have lived or been born had removal not occurred were wiped from the face of the earth. Such death tolls must also be understood in the context of the loss of land. Indeed, for Choctaws, separation from their homeland meant for them death, and Choctaw conceptions of the West as a place where spirits were lost only compounded their misery, sense of loss, and despair for the future. One of their leaders, a man named George Washington Harkins, understood all of this. As he departed his homeland, his mother earth, on a steamer bound for Fort Smith, Ark., he mourned the total destruction of his people’s world. “We found ourselves,” he wrote from the ship’s railing, “like a benighted stranger, following false guides until surrounded by fire and water—the fire is certain destruction, and a feeble hope was left of escaping by water.”

For the Mississippi House Indian committee, however, the removals, the deaths, and the despair augured a new beginning, “the dawn of an era . . . when . . . this state would emerge from obscurity, and justifiably assume an equal character with her sister states of the Union.” Indeed, to the United States, the removals were a triumph. Land had been opened for settlement, the “Indians” had been saved, and the unrelenting expansion into the West could continue unabated. But what did the South lose with the removals? Were the removals acts of ethnic cleansing akin to what happened in the Balkans in the late 20th century? And why are not “Indians” remembered in the same way that the slaves and planters of the early 19th century South are? Is it because they were removed from our memories as well? Such questions suggest that even today we have failed to come to grips with what removal meant to the South then and what it means to the South today.

JAMES TAYLOR CARSON

Queens University

Donna Akers, American Indian Culture and Research Journal (1999); James Taylor Carson, Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal (1999); Michael D. Green, Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis (1982); Lucy Maddox, Removals: Nineteenth-Century American Literature and the Politics of Indian Affairs (1991); Ronald Satz, American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era (1975); Russell Thornton, in Cherokee Removal: Before and After, ed. William L. Anderson (1991).

Native Americans and African Americans

Native peoples in the South and African newcomers to North America first encountered one another at least by the early 16th century when Africans traveled through the indigenous Southeast with Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto. De Soto’s ruthless 1539–40 expedition in which he pillaged for gold and Indian slaves included more than 600 soldiers, some of whom were enslaved blacks. In the wealthy Mississippian chiefdom of Cofitachequi (present-day South Carolina), the de Soto party met a woman chief known thereafter as “the Lady of Cofitachequi.” Draped in a fine white fabric, the Lady was carried on a litter and transported in a decorative canoe by slaves from another indigenous group. De Soto and his men plundered pearls, desecrated the temple, and took the Lady captive. She escaped into the woods with a cache of recovered pearls and later encountered a group of enslaved, Spanish-speaking soldiers who had also stolen away from de Soto’s party. The Lady of Cofitachequi partnered with a black man from this group in perhaps the first recorded example of Native American and African (American) marriage. The layered context of their coupling—European invasion, greed, violence, multinational slavery, and the quest for freedom and belonging—would also influence Native American and black relations to come.

A century after this encounter, hundreds of “charter generation” Africans arrived on slave ships to labor in European colonies. When Africans first appeared at the side of Europeans on Atlantic shorelines or in newly established frontier settlements in Virginia or Carolina, speaking European languages and wearing European clothing, they would have been grouped with Europeans by Native American observers who drew lines of distinction around cultural practice rather than race. Not until the early 1700s for tribes that traded most heavily with Europeans, and the late 1700s for geographically isolated tribes, did Native people witness and absorb the organizing principle of racialized chattel slavery. As the English held a growing number of dark-skinned Africans in permanent and inheritable chattel bondage, Native people could not help but recognize race as a marker of difference that mattered.

Concurrent with the importation of black slaves was the rise of an Indian slave trade in the middle and late 1600s. Southern Indians had long taken captive members of enemy Native groups and kept those who were not adopted or ritually murdered as slaves. However, the scale and purpose of Indian slavery shifted as European colonists sought capital to finance plantations through the sale of human beings, as well as an inexpensive labor force with which to derive value from usurped Native lands. European planters incentivized and coerced Indians to sell captives taken in intertribal conflicts. In order to ensure their supply of highly valued trade goods and to protect their own communities from attack, groups like the Westos and the Chickasaws engaged in slaving raids to provide captives to the English. As the European quest for slaves mushroomed, the Indian slave trade enveloped most southern nations, catapulting them into excessive intergroup conflict, population loss, forced migration, and retrenchment as confederacies. At the same time that an African diaspora was being forged through the dispersal of enslaved blacks, an “American diaspora” was being shaped through the dispersal of enslaved Native Americans.

Many of these Indian slaves were sold to the Caribbean, Europe, and New England; some were sold to the Upper South, and the minority was retained in the Lower South. Charles Town was the main location for the sale of both black and Indian slaves, who stood on the same auction blocks and traversed the Atlantic on the same ships. As blacks and Indians were both ensnared in the changing dynamics of human slavery, the merger of lives, communities, and cultures followed. Intermarriage between blacks and American Indians took place on southern plantations, as evidenced by descriptions of mixed-race runaway slaves in colonial newspaper advertisements. In addition to intermarriage, shared circumstances of enslavement led to the exchange and re-creation of cultural forms. African concepts of place, holistic spirituality, respect for ancestors, and the oral tradition corresponded with Native American notions, thereby facilitating this process. Cultural practices that reflect black and Native comingling in the South include a corn-based Indian diet that influenced black “soul food,” the augmentation of black women’s basket-weaving skills with Native patterns and plant preferences, black men’s dugout canoe building learned from Indian companions, cross-cultural influences in Colonoware pottery recovered by archaeologists in Indian towns and on Virginia and South Carolina plantations, plant use as herbal medicines and gourd use as containers, and trickster rabbit story traditions that share character, theme, and plot connections.

Small but noteworthy numbers of free and runaway blacks moved through Native communities in the 1700s. They did so at first as cultural and familial outsiders. Because blacks lacked kinship ties, they were treated as foreigners and held at a distance until or unless they established connections. Such ties were most successfully based in kinship relationships through intermarriage or adoption into Native clans. However, Africans without demonstrable links to Native communities could face suspicion, exclusion, and harsh treatment, as did any uninvited outsider. While one “Negro Fellow” who sought to trade with the Catawbas was met with anger in the 1750s, another “free Negro . . . live[d] among the Catawbas, and [was] received by them as a Catawba, that [spoke] both their language and English, very well.” In these early years of black and Native interaction, race was not a distinguishable factor. Native people instead determined how they would relate to Africans on a case-by-case basis, depending on circumstance, cultural dictates, and mutual need. Blacks seeking free spaces and better lives would also have assessed the Native people they encountered with discernment.

Native slavery decreased after 1720 and was gradually outlawed in the southern colonies by the mid- to late 1700s. But even as the Indian slave trade faded and the importation of Africans skyrocketed, Native people remained aware of the threat of the Euro-Americans’ expanding race-based plantation regime. Witnesses to and previous victims of the brutality of chattel slavery reserved for dark-skinned peoples, Native Americans feared the continuing seizure of their lands and also being grouped with “a great ‘colored’ underclass.” The major southern tribes that survived the “shatter zone” of the Indian slave trade and consolidated their peoples—the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws—began to draw their own color lines and practice race slavery by the turn of the 19th century.

The outcome of the American Revolutionary War, in which the major southern tribes had aided the British, placed increased pressure on these nations to adopt white American ways of life, including race slavery. As U.S. representatives pushed “civilization” and urged Indian men to give up hunting and turn to agriculture, they also modeled and encouraged black slave ownership. The first treaties negotiated with the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws after the war took place on the Hopewell plantation of Brig. Gen. Andrew Pickens in 1785–86. With black slaves in the background presenting a cautionary contrast, Indians were assured that the Continental Congress would promote their welfare “regardless of any distinction of colour.” After the Hopewell treaties had secured large land cessions, Benjamin Hawkins, U.S. agent for southern Indian affairs, developed a model plantation complete with black slaves.

By the early 1800s, minorities within the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek nations held black slaves on small farms and large plantations. Native slaveholders sometimes inherited blacks from white fathers, held blacks taken in the Revolutionary War, and traded for blacks in Indian towns and southern cities. Native governments sanctioned slavery and black political exclusion, and prohibitions against intermarriage developed in the Cherokee and Creek nations in the 1820s. Nevertheless, intimate relations across the color line persisted in slaveholding Indian nations. Some of these couplings were engaged in by choice; others were coerced or forced. The experience of blacks owned by Indians differed depending on circumstance but in many ways echoed that of slaves in the white South. Blacks enslaved by Native people resisted in various ways, including escape. Those who remained in Indian bondage learned Native languages, prepared Indian foods, and wore Indian dress. Native slaveholders’ dependence on black slaves’ linguistic and interpretive skills in missionary, trading, and treaty negotiation contexts is widely documented and distinguishes black slavery in Indian locales.

Among the large slaveholding tribes, the Seminoles were exceptional. They were themselves a nation made up of survivors—runaways and refugees of various Indian groups, particularly Creek minorities. Rather than adopting chattel slavery, Seminoles created a system that borrowed from older Native chiefdom models of central and dependent towns. Aware of the uniqueness of Seminole views, black slaves fled to Florida and established towns of their own within Seminole territory. With an estimated population of 800 in 1822, Seminole maroon communities thrived, paying a required tribute in crops to powerful Seminole towns. While black Seminoles were not formally free, they lived lives characterized by relative autonomy and mobility. Interracial marriage between blacks and Seminoles occurred but was not the norm, as social life focused within rather than across the settlements. Black headmen emerged not only as leaders of black Seminole towns but also as go-betweens, and black male interpreters served in diplomatic talks between the Seminoles and the United States. In the First and Second Seminole Wars (1817–18, 1835–42), waged with the United States over Florida lands, black Seminoles fought alongside Seminoles, who in turn protected them from being returned to slavery in the states. Maj. Gen. Thomas Jesup’s warning to the secretary of war—“The two races, the negro and the Indian, are rapidly approximating; they are identified in interests and feeling”—captured the strength of the alliance as well as the anxiety it caused. The alliance faltered, however, when Jesup offered freedom to black Seminoles if they abandoned the resistance movement and immigrated to Indian Territory. After Seminole removal, bands of Seminoles and black Seminoles led by former warriors Wildcat and John Cavallo (Horse) continued the alliance and departed Indian Territory for Mexico together. However, relations as a whole deteriorated in the West, and the interdependent chiefdom system was not restored.

Following the Indian removal period of the 1830s and 1840s, Native Americans and African Americans in the South came into significant contact at Hampton Institute in Virginia. A black industrial school by design, Hampton became a biracial institution and an early site of government-funded education for Indians at the start of the boarding-school era. Indians first entered Hampton in 1878, 10 years after the school’s founding, when Capt. Richard Henry Pratt transported Plains tribes prisoners of war to study under the directorship of Hampton founder Samuel Chapman Armstrong. The goal of educating Native students at Hampton was civilizational and industrial training, as Indians were expected to learn habits of white society that would enable their cultural transformation and eventual assimilation. In 1879, when Hampton launched its Indian Program, Native students studied alongside blacks in a regimented, semisegregated setting that encouraged racial comparison and competition. School administrators imagined black students as willing workers because of the legacy of slavery, while they pictured Indians as wild, proud, and hostile to whites. Placed higher on a projected scale of civilization, black students were expected to set an example of good cheer and hard work for Indians. Notions about black and Indian students at Hampton fluctuated, however, with each group being shifted on an ideological hierarchy of races. The Hampton Indian program ended in 1922, in large part owing to the loss of congressional funding in 1912 and a growing inability to recruit Indian students to attend a predominantly black institution at a low point in African American history.

Native American and African American interrelated cultural lives have been rich, complex, and varied. Brought together in the 1500s by European exploration, colonization, and slavery, thousands of Native Americans and African Americans came into intimate contact by circumscribed choice as well as duress. They forged familial, cultural, and political connections and engaged in intergroup conflicts that continue to reverberate. Together with whites, blacks and Indians were important, if often unwilling, partners in the forging of a new southern world.

TIYA MILES

University of Michigan

Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (1998); Kathryn E. Holland Braund, Deerskins and Duffels: Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815 (1993); Jonathan Brennan, ed., When Brer Rabbit Meets Coyote: African–Native American Literature (2003); Chester B. Depratter, in The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521–1704, ed. Charles Hudson and Carmen Chaves Tesser (1994); Robbie Ethridge and Sheri M. Shuck-Hall, eds., Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South (2009); Jack D. Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples (1993); Thomas Foster, ed., The Collected Works of Benjamin Hawkins, 1796–1810 (2003); Alan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717 (2002), ed., Indian Slavery in Colonial America (2009); Charles Hudson, Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms (1997), The Southeastern Indians (1976); Barbara Krauthamer, in New Studies in the History of American Slavery, ed. Edward E. Baptist and Stephanie M. H. Camp (2006); Almon Wheeler Lauber, Indian Slavery in Colonial Times within the Present Limits of the United States (1970); Donal F. Lindsey, Indians at Hampton Institute, 1877–1923 (1995); James H. Merrell, Journal of Southern History (August 1984); Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (2010), Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (2005); Patrick Minges, Black Indian Slave Narratives (2004); Kevin Mulroy, Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas (1993); Celia Naylor, African Cherokees in Indian Territory: From Chattel to Citizens (2007); Greg O’Brien, ed., Pre-removal Choctaw History: Exploring New Paths (2008); Theda Perdue, Ethnohistory (Fall 2004), Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540–1866 (1979); Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, eds., The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southeast (2001); Kenneth W. Porter, The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People (1996); Claudio Saunt, Black, White, and Indian: Race and the Unmaking of an American Family (2005), in Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America, ed. James F. Brooks (2002); Claudio Saunt et al., Ethnohistory (Spring 2006); Theresa A. Singleton, ed., I, Too, Am America: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life (1999); Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (2010); Gabrielle Tayac, in Documents of United States Indian Policy, ed. Francis Paul Prucha (1975; 1990), ed., IndiVisible: African–Native American Lives (2009); Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (1974); J. Leitch Wright, The Only Land They Knew: The Tragic Story of the American Indians in the Old South (1981); Gary Zellar, African Creeks: Estelvste and the Creek Nation (2007).

Pacific Worlds and the South

Often depicted as isolated and xenophobic, at least in relation to other parts of the United States, the American South at first glance appears to have little relevance to lands and peoples across the Pacific. But the South’s transpacific connections run deep. And it is through those connections forged by empire and capital that Asians have arrived in the South (and the Americas in general). Indeed, within the field of Asian American Studies, the South is where that history first took root. When the Spanish claimed the Americas and the Philippines in the 16th century, they envisioned and pursued an imperial world of mercantile capitalism, including the galleon trade plying between Manila and Acapulco. It was not uncommon for Filipino sailors, who had been impressed to work on the galleons, to jump ship in Mexico. Possibly as early as the 1760s, when the Spanish Crown ruled over Louisiana, some of these sailors sought refuge in St. Bernard Parish, establishing perhaps the oldest Asian American community in the present United States.

As the example of Louisiana’s Manilamen, as they would be called, suggests, the South was not always what it has become (or, more precisely, what it has come to represent)—a region within the United States, usually defined by its distinctly biracial (black-white) history. The Spanish, French, British, and American empires have laid claims to different parts of southeastern North America, making it, at varying points, the northern, eastern, western, or southern node in wider imperial formations. (Our geohistorical groundings would become more unsettled if we were to include the perspectives of American Indians.) Exploring how and why Asians have come to call the South home, if only temporarily at times, compels us to contend with these larger histories, to see the South’s imbrication in national and global developments that were never simply black and white, North and South, or West and East.

New Orleans, the Old South’s leading port city, and the surrounding sugar parishes constituted the southern hub of ideas and movements concerning Asia and Asians in the 19th century. For proslavery ideologues like J. D. B. De Bow, Asia and Asians were very much at the heart of struggles over American slavery. Observing the transport of thousands of indentured Asian workers to British, Spanish, and French colonies of the Caribbean in the 1840s and 1850s, the influential journalist of New Orleans denounced what he saw as the hypocrisy of abolitionism. “The civilized and powerful races of the earth have discovered that the degraded, barbarous, and weak races may be induced voluntarily to reduce themselves to a slavery more cruel than any that has yet disgraced the earth,” De Bow concluded, “and that humanity may compound with its conscience, by pleading that the act is one of free will.” If condemning their Caribbean neighbors’ resort to Asian workers helped to justify American slavery, the Civil War and its aftermath drew southern planters’ eyes increasingly to Asia and the Caribbean. “Those pent-up millions of Asia want room, want food, want the opportunity to work,” a southern champion of Chinese labor argued in 1868; “we, in the Valley of the Mississippi, want labor; we must have it; we have farms for millions, work for tens of millions.”

With the onset of Radical Reconstruction, southern planters’ fascination with Asian workers as a potential alternative to black labor reached a feverish pitch, enough to generate a mass regional convention in Memphis, Tenn., in July 1869. In both the South and the Caribbean, a leading organizer of the meeting stated, “experience taught that the great staples could not be produced by voluntary labor, but under coerced labor systematized and overlooked by intelligence . . . labor that the owner of the soil can control.” He and many of the delegates clamored openly for a new form of slavery, labor “which you can control and manage to some extent as of old.” With discussions on labor conditions in the Caribbean, Hawaii, California, and elsewhere, the Memphis convention also conveyed the New South’s worldly (and imperial) ambitions. Its delegates resolved to form the Mississippi Valley Immigration Labor Company to bring “into the country the largest number of Chinese agricultural laborers in the shortest possible time,” with an invitation to “capitalists and planters” everywhere to purchase stocks. It was a resolution and a movement simultaneously to revive slavery and to modernize the South.

Such brash talk of recruiting “coerced” workers from Asia generated vehement opposition from two seemingly dissimilar sources, reflective of intensifying battles over Reconstruction and Chinese migration. Fearful of southern white designs to thwart recent political advances, prominent abolitionists and Republicans objected to what Frederick Douglass called “the selfish inventions and dreams of men!” Immediately after the Memphis convention, Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell instructed the New Orleans collector of customs “to use all vigilance in the suppression of this new modification of the Slave Trade.” The growing ranks of dispossessed whites in the South likewise rejected the prospect of Asian workers flooding the region, not for humanity’s sake but for their own salvation. “We will have again a fat and pampered aristocracy, worse than it ever was, and far more haughty and overbearing,” an antiplanter editorial declared. “It will then be ‘how many Coolies does he work?’ instead of ‘how many negroes does he own?’ so commonly used ante bellum.” Echoing anti-Chinese rancor on the Pacific Coast, many southern whites articulated and translated their critique of monopoly capital in racial terms.

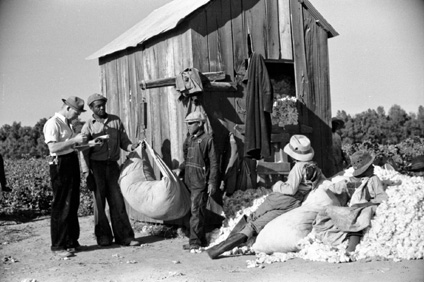

These local, national, and global forces firmly linked Asian workers with slavery in American culture and, in turn, steered thousands of Chinese migrants to the South, especially Louisiana, in the 1860s and 1870s. Largely restricted to the richest planters, who could afford the high costs of recruitment and shipment, a coterie of southerners, targets of fanfare and optimism as much as of chagrin and scorn, pursued Chinese workers on imperial routes crisscrossing the globe—from Cuba, China, Martinique, and, increasingly after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, California. “Physically they are fine specimens, bright and intelligent,” the New Orleans Times rejoiced, “and coming, as they do, from the low districts of China, within the tropics, there is nothing to be apprehended on the score of climate.” But Chinese migrants failed to solve planters’ labor “problems,” for they behaved no differently than black workers. Planter after planter drew the same conclusion—the Chinese were “fond of changing about, run away worse than negroes, and . . . leave as soon as anybody offers them higher wages,” as a newspaper put it—even as they ironically and continually lured Chinese workers away from their neighbors’ estates, with the hope of stabilizing their labor force.

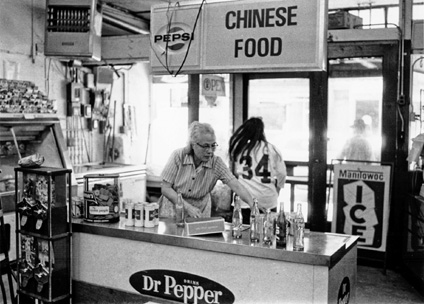

As Chinese workers ran away to various plantations, to small towns and larger cities, and to California and elsewhere, they seemed to vanish from the South as fast as they had appeared. Outside the public eye, however, many Chinese migrants formed families and communities, with one another and with local peoples. They made the South their home. In Natchitoches Parish, La., for example, Chinese men established families with black, white, Creole, and American Indian women, whose progeny have continued to recognize (and at times vehemently deny) their Chinese ancestry for generations. U.S. census records failed to capture their diverse histories though. In 1880, the multiracial children of Chinese migrants were categorized as “Chinese,” but within two decades, amid the onslaught of Jim Crow laws, those same individuals were reclassified as either “black” or “white.” Later on, some embraced their “Mexican” identity, a classification that enabled them to straddle the hardening color line. In contrast to their forebears, who were in demand as plantation workers precisely because they were neither black nor white, most descendants of Chinese migrants were compelled to identify as either black or white in the 20th century.

As in other regions of the United States, Asian Americans in general had no choice in racial matters. The state decided for them. Born and raised in the segregated world of Mississippi, Martha Lum and her parents attempted to enroll her in the all-white Rosedale Consolidated High School in 1924. Readily admitting that their client was not white, Lum’s lawyers simultaneously insisted that she was not “colored,” which, they argued, had been defined historically as persons with “negro blood.” Placing the “Mongolian” apart from the “colored” and next to the “Caucasian,” Lum’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court rested on doubling (and troubling) claims of racial discrimination. “The white race may not legally expose the yellow race to a danger that the dominant race recognizes and, by the same laws, guards itself against,” Lum’s lawyers pleaded. “This is discrimination.” The highest courts of Mississippi and then the United States disagreed. Upholding Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and other legal precedents on racial exclusion and segregation, they ruled that Lum “may attend the colored public schools of her district, or, if she does not so desire, she may go to a private school.” She was indeed “colored.”

U.S. military campaigns across the Pacific, which began in the 19th century and proliferated in the 20th century, have driven new waves of Asians to the South. In the wake of U.S. entry into World War II, the federal government rounded up Japanese Americans living along the Pacific Coast and ordered them at gunpoint to embark on a trail of dispossession and misery eastward. Tens of thousands of them ended up in the South, incarcerated in concentration camps (in Rohwer and Jerome) in Arkansas and internment camps in Texas and Louisiana and inducted into a segregated military unit in Mississippi. “Being at Rohwer was just a lonely feeling that I can’t explain,” recalled Miyo Senzaki. “You couldn’t run anywhere. It was scary because there was no end to it. You could run and run and run but where are you to go? . . . We felt like prisoners.” Though victims of segregation before World War II, for many Japanese Americans, including the legendary activist Yuri Kochiyama, it was in Arkansas and Mississippi that they awakened to a new political consciousness, a new awareness of white supremacy’s reach and depth. Jim Crow in the concentrations camps, in the military, and in the surrounding southern landscape ruled their lives.

Three decades later, U.S. military intervention in Southeast Asia drove thousands of refugees to the South, a flow of Asian migrations created by the colossal U.S. military industrial complex and the living legacies of Spanish, Portuguese, and French colonialisms. Among the first to arrive in 1975 were Vietnamese Catholics, whose religious lineage dates back to Spanish and Portuguese colonizers of the 16th century and French colonial rule beginning in the 19th century. Deemed collaborators of French rule and then of the U.S. military by the Communist leaders of Vietnam, Vietnamese Catholics sought refuge for decades, first in southern Vietnam (after the decisive defeat of French troops in 1954) and then in the United States and elsewhere (upon the “fall” of Saigon in 1975). These refugees were first flown to Guam and the Philippines and then to four military bases on the U.S. mainland, including Camp Chafee in Arkansas and Elgin Air Force Base in Florida, from which volunteer organizations sponsored them for resettlement across the United States. Thousands of Vietnamese refugees accepted an open invitation from the head of the New Orleans archdiocese, finding a refuge, a new home, in a Catholic city, not far from where the Manilamen had landed two centuries earlier.

Vietnamese refugees and their families were among those devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, a storm that pushed race to the fore of U.S. politics, albeit framed almost universally in black and white. Largely below the media radar, racial dynamics in the Village de L’Est neighborhood of New Orleans were radically different. With mass white flight since the 1960s, it was a neighborhood made up almost completely of blacks and Vietnamese. In Katrina’s aftermath, both Vietnamese and black residents returned much earlier and in larger numbers than anticipated or desired by city, state, and federal officials. Almost immediately upon their return, they encountered a new threat nearby, in the form of a makeshift landfill ordered into existence by Mayor C. Ray Nagin. With support from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Martin Luther King Jr.’s organization, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and other civil rights groups, local residents mobilized successfully to shut it down. “The landfill struggle, everything we’re fighting for out here—this is about the Vietnamese and the blacks together,” a Vietnamese American organizer stated. Village de L’Est is a neighborhood not devoid of racial tensions and conflicts, but, like many rural and urban pockets across the South today, it is a place of complex memories and histories, a place that growing numbers of Asian Americans are calling home.

MOON-HO JUNG

University of Washington

Leslie Bow, Partly Colored: Asian Americans and Racial Anomaly in the Segregated South (2010); Sucheng Chan, Asian Americans: An Interpretive History (1991); Lucy M. Cohen, Chinese in the Post–Civil War South: A People without a History (1984); Marina E. Espina, Filipinos in Louisiana (1988); Diane C. Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (2005); Gong Lum et al. v. Rice et al., 275 U.S. 78 (1927); Moon-Ho Jung, Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation (2006); Karen J. Leong et al., Journal of American History (December 2007); Gary Y. Okihiro, Margins and Mainstreams: Asians in American History and Culture (1994); Rice et al. v. Gong Lum et al., 139 Mississippi 760 (1925); Eric Tang, American Quarterly (March 2011); John Tateishi, ed., And Justice for All: An Oral History of Japanese American Detention Camps (1999).

Racial Terror and Citizenship

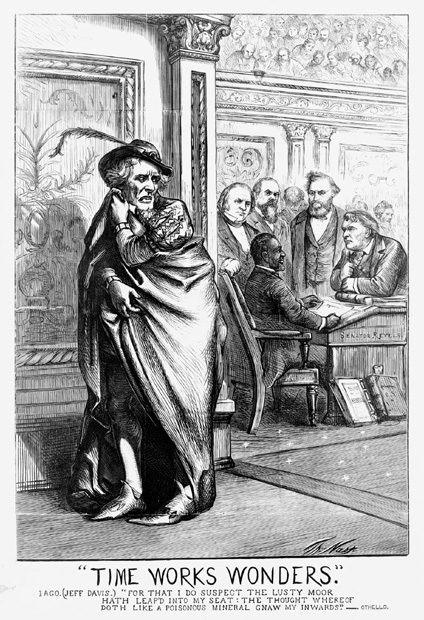

“There is a perfect reign of terror existing in the several counties, so much so that I cannot do justice to the subject,” wrote an official with the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in 1866. The phrase this superintendent chose to characterize the late-night home invasions, plunder, murder, and rape being carried out by a vigilante gang of white men against former slaves in his region of Tennessee—“a perfect reign of terror”—appeared repeatedly in official descriptions of similar white-on-black violence that occurred across the South after the Civil War. This violence was generally well planned and carried a clear political message: regardless of their new status as free people, African Americans would not be permitted to exercise the rights of citizenship. It also initiated patterns of racial and political violence that endured across the South well into the 20th century.

During Reconstruction, former slaves seized opportunities for political participation, while the federal government—through legislation and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments—recognized them as citizens and guaranteed the right to vote without regard to race. Active black citizenship, though, upended a southern antebellum political culture wherein a voice in public affairs had been the exclusive privilege of white men. Black male suffrage threatened not only white men’s control over politics but also the significance of their whiteness, which had previously depended on a clear distinction between white “freemen” and black slaves. Violent white reactions to the challenges posed by emancipation began immediately after the war, when bands of white men roamed rural areas of the South, disarming black Union soldiers, stealing freedpeople’s property, and threatening and often killing black community leaders. The “reign of terror” also included “riots”—in fact, premeditated massacres of freedpeople—in cities such as Memphis and New Orleans. It was repeated scenes of such violence in the former Confederacy that convinced many northern white Republicans to support federal protection of black rights in the South, and specifically suffrage. Yet as the resultant federal law took effect in the late 1860s, white-on-black violence only spread into widening realms.

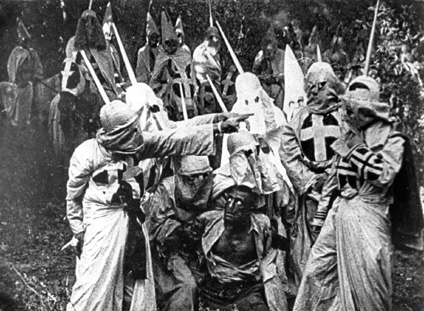

At this time, vigilante gangs began wearing disguises and calling themselves the Ku Klux Klan. The Reconstruction-era Klan, though, was far less a centralized organization than a label used by disparate white gangs across the South who sought the anonymity offered by Klan-style practices. Attacks by these disguised bands followed a common pattern. Late at night, masked men surrounded freedpeople’s homes, dragged their victims outside, plundered their belongings, and stripped, beat, whipped, raped, or murdered them. White vigilantes also subjected many to scenes of racial and sexual submission. Through their words and deeds, assailants compelled their victims to enact a return to a pre-emancipation racial order, that is, one in which black men were rendered incapable of protecting their families and black women were obliged to provide white men with sex on demand. In effect, assailants attempted to impose upon black men and women their putative unsuitability for citizenship by forcing them to perform dishonorable masculine and feminine roles.

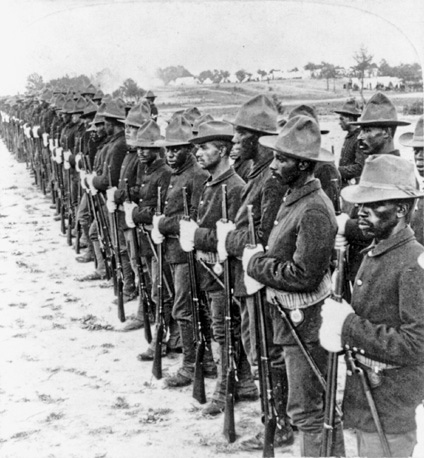

Many African Americans responded to Klanlike attacks by participating in local militias to protect their communities from violence. Especially in rural areas where African Americans were in the minority, though, the power of terrorist gangs frequently overwhelmed local law enforcement. Indeed, some gangs included police officials as members. Some Reconstruction-era governors imposed martial law to put down the Klan, but in most states only federal action was effective in stopping the violence. In 1870–71, the Enforcement Acts made violence or intimidation with the intent of impeding voting a federal offense, allowing the federal government to oversee elections and to arrest Klan members. Under these acts, hundreds were prosecuted. Although few served significant jail time, Klanlike vigilante terrorist groups were effectively ended for the time being. Suppressing the violence led to an impressive expansion of black political participation between 1872 and 1874.

This high point in black political power, though, also marked the beginning of the next round of terrorist violence in the South, as armed auxiliaries of the Democratic Party mounted new campaigns to push African Americans out of the political process. African Americans organized in self-defense but were usually out-armed and out-numbered, and hundreds were killed in clashes during the mid-1870s. In summer 1876, a federal official again used the familiar phrase “a perfect reign of terror” to describe the violence in one region of South Carolina. But this time attackers operated in the open, emboldened by an apparent federal retreat from backing African Americans’ rights in the South. This retreat was evident when, in United States v. Cruikshank et al. (1876), the Supreme Court overturned convictions under the Enforcement Acts, arguing that the federal government had authority only over actions taken by states, not individuals. Thereafter, the power to police vigilante violence returned to state governments, which were now all under Democratic control and often complicit in terror.

With the alliance between African Americans and northern white political leaders that had made possible the Reconstruction era’s dramatic revolution in citizenship now ended, the threat of violence rather than the force of law would regulate the exercise of political power in the South for decades to come. Not until the 1960s did renewed federal attention drive white terror underground, from where assailants nonetheless carried out plans to bomb black churches and to kidnap and murder civil rights activists. White violence thus effectively barred African Americans from the citizenship they had sought, and had momentarily enjoyed, after emancipation until the civil rights movement’s successes a century later.

HANNAH ROSEN

University of Michigan

Jane Dailey, Before Jim Crow: The Politics of Race in Postemancipation Virginia (2000); Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution (1988); Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 (1996); Steven Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (2003); Stephen Kantrowitz, Ben Tillman and the Reconstruction of White Supremacy (2000); Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (2009); Allen W. Trelease, White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (1971).

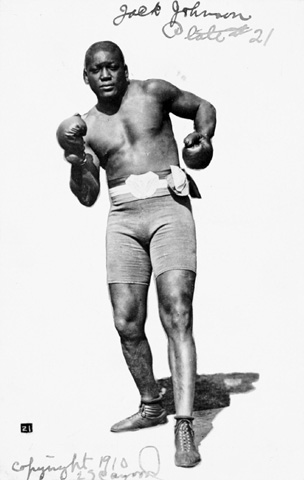

Racial Uplift

Racial uplift is an African American ideology that had its greatest impact in response to the increasing oppression blacks faced between 1880 and World War I. Earlier versions of its concern for achieving social respectability in the eyes of whites appeared in the North before the Civil War, among free blacks trying to claim their rights. The end of slavery and the gaining of freedom for southern slaves led to an optimistic period for African Americans during Reconstruction. But the frustration that came afterward with Jim Crow segregation laws, disfranchisement, economic marginalization, bigoted and crude representations in American culture, and racial violence led to a variety of efforts to counter white racism, with leaders advocating for public protest, migration, industrial education, or higher education. In this context, the black middle class embraced the idea of uplift, a belief that advocates who called themselves the “better classes” should nurture black respectability as a way toward social advancement. This outlook called for black elites to assume responsibility for working with the black masses to encourage them to follow middle-class values of temperance, hard work, thrift, perseverance, and Victorian-era sexual self-restraint. The expectation was that as most blacks came to practice middle-class virtues, they would earn the esteem of white America.

The ideology countered antiblack stereotypes by stressing class differences among African Americans, with black elites the symbols of racial progress. Its advocates demanded recognition by white elites of the role of black elites as torchbearers for “civilization” and “progress.” This approach encouraged intraracial class tensions and overlooked the deeply racialized categories of civilization and progress in the age of empire and the “white man’s burden.” By endorsing the idea of backward black masses, racial uplift ironically seemed to endorse the white racist representations of blacks. In the realm of culture, racial uplift endorsed Western European forms of music. The Fisk Jubilee Singers, for example, converted the folk spirituals of slavery into a choral style that would appeal to white audiences as they toured the nation and Europe itself. Black middle classes disliked, in turn, the raw emotions of blues music and black gospel music, seeing them as survivals from a primitive age of black culture. Black elites did not appreciate ways that black folk culture offered individual psychological resources and communal social class cohesion to counter the trauma of white racism.

The ideology was firmly patriarchal in its assumption that male-headed families should be the norm, with male authority sometimes taken for granted, although black women leaders often challenged this latter assumption. African American women, in fact, were among the chief advocates for racial uplift and were responsible for some of its greatest achievements. The black Baptist Women’s Convention Movement drew from an emergent middle class in the late 19th century of school administrators, journalists, businesswomen, and social reformers that served an all-black community in the age of Jim Crow. Black religious women promoted bourgeois ideals as missionaries, teachers, and sometimes just as influential wives of ministers, all of which made them conveyers of culture to the larger black community. They also vocally attacked the nation’s failure to live up to its ideals. One of the most prominent Black Baptist women leaders was Nannie Burroughs, who was the first president of the National Baptist Convention’s National Training School for Women and Girls. She had introduced the idea for the school to the Women’s Convention and stoked enthusiasm for it. “This is going to be the ‘national dream’ realized,” she wrote, insisting that “a million women in our churches will make us have it.” The convention’s interest in the welfare of the working poor and its interest in employment possibilities after graduation led to founding the institution as an industrial school rather than a liberal arts college. Its motto was “Work. Support thyself. To thine own powers appeal.” The school’s founders saw productive labor as contributing to individual self-help and responsibility, but it also encouraged “race work,” pride in racial identity and responsibility for the collective black community.

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) became a prime organizational context for African American women to promote the middle-class ideals of uplift. The image of the drunken husband and father had no innate racial component, but black women reformers saw how whites often represented that figure as a black man. They argued that alcohol had a pernicious effect not only on families but on the black community in general. They used the WCTU to show that black leaders were witnessing for temperance with dignity and industriousness, and that not all blacks failed to achieve this particular middle-class ideal. Working for temperance brought black women uplifters into collaborative work with white women, in a conspicuous example of interracial cooperation for the time period. White women saw black women, though, as junior partners in the collaboration, working in a segregated institution and reporting to white women. At a time when some African Americans were still able to vote, white women recognized the potential for recruiting black voters in temperance elections, encouraging this cross–racial line cooperation. Black women reformers had long worked through churches for temperance reform and resented the often-patronizing attitudes of white women. Still, black women saw in the WCTU the opportunity to build a Christian community that might serve as a model for interracial cooperation on other fronts, which could aid very tangibly the social needs of the black masses.

Black ministers were also among the most important and successful advocates for racial uplift. The ideology had roots in the communal religious activities of the slave community before the Civil War, and the New Testament ideal of community offered a specifically religious theology supporting the concept. The Christian image of the shepherd inspired black ministers as they rose in denominational hierarchies, and they affirmed the need to care for less-fortunate blacks and to inculcate the Protestant work ethic as an illustration of racial uplift ideals. The National Baptist Convention (NBC) supported both industrial education and higher education as vehicles for middle-class black aspirations, and both Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois were often in attendance at the convention’s activities. Black religious leadership of the era often reflected a Gilded Age success formula. Thomas Fuller, for example, the minister of a large Nashville congregation at the turn of the 20th century, preached a popular sermon, “Work Is the Law of Life,” which projected an optimistic, self-help philosophy encouraging his hearers to success through hard work. Another black minister, Elias Camp Morris, was the first president of the NBC, beginning in 1895, and remained its leader for a quarter of a century. He urged blacks to support “the business side of the race” by patronizing black-owned businesses. He urged that there be no let-up “of our efforts to become taxpayers, owners of homes, and constructive builders of our own fortunes.”

Although the racial uplift ideology had its limitations, it counted many solid achievements in terms of social improvements for African Americans at a time regarded as the nadir for black life in the South and the nation. Advocates worked through schools and colleges, civic and fraternal organizations, Social Gospel churches, settlement houses, newspapers, and trade unions to improve the life of black communities. The ideology failed, though, in its assumption that embracing middle-class values would overcome the disadvantages from American society’s racist structures that stacked the deck against those very middle-class aspirations of African Americans.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Kevin Gaines, Uplifting the Race: Black Middle-Class Ideology and Leadership in the United States since 1890 (1996); Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (1994); Angela Hornsby-Gutting, Black Manhood and Community Building in North Carolina, 1900–1930 (2009); Karen Ann Johnson, Uplifting the Women and the Race: The Educational Philosophies and Social Activism of Anna Julia Cooper and Nannie Helen Burroughs (2000); Edward Wheeler, Uplifting the Race: The Black Minister in the New South, 1865–1920 (1986).

Religion, Black

The religious life of the majority of black southerners originated in both traditional African religions and Anglo-Protestant evangelicalism. The influence of Africa was more muted in the United States than in Latin America, where African-derived theology and ritual were institutionalized in the communities of Brazilian Candomblé, Haitian Voodoo, and Cuban Santeria. Nevertheless, in the United States, as in Latin America, slaves did transmit to their descendants styles of worship, funeral customs, magical ritual, and medicinal practice based upon the religious systems of West and Central African societies.

Although some slaves in Maryland and Louisiana were baptized as Catholics, most had no contact with Catholicism and were first converted to Christianity in large numbers under the preaching of Baptist and Methodist revivalists in the late 18th century. The attractiveness of the evangelical revivals for slaves was due to several factors: the emotional behavior of revivalists encouraged the type of religious ecstasy similar to the danced religions of Africa; the antislavery stance taken by some Baptists and Methodists encouraged slaves to identify evangelicalism with emancipation; blacks actively participated in evangelical meetings and cofounded churches with white evangelicals; and evangelical churches licensed black men to preach.

By the 1780s, pioneer black preachers had already begun to minister to their own people in the South, and as time went on, black congregations, mainly Baptist in denomination, increased in size and in number, despite occasional harassment and proscription by the authorities. However, the majority of slaves in the antebellum South attended church, if at all, with whites.

Institutional church life was not the whole of religion for slaves. An “invisible institution” of secret and often forbidden religious meetings thrived in the slave quarters. Here slaves countered the slaveholding gospel of the master class with their own version of Christianity in which slavery and slaveholding stood condemned by God. Slaves took the biblical story of Exodus and applied it to their own history, asserting that they, like the children of Israel, would be liberated from bondage. In the experience of conversion, individual slaves affirmed their personal dignity and self-worth. In the ministry, black men exercised authority and achieved status nowhere else available to them. Melding African and Western European traditions, the slaves created a religion of great vitality.

Complementing Christianity in the quarters was conjure, a sophisticated combination of African herbal medicine and magic. Based on the belief that illness and misfortune have personal as well as impersonal causes, conjure offered frequently successful therapy for the mental and physical ills of generations of African Americans and simultaneously served as a system for venting social tension and resolving conflict.

The Civil War, emancipation, and Reconstruction wrought an institutional transformation of black churches in the South. Northern denominations—black as well as white—sent aid to the freedmen and missionaries to educate and bring them to church. Freedmen, eager to learn to read and write, flocked to schools set up by the American Missionary Association and other freedmen’s aid societies. These freedmen’s schools laid the foundation for major black colleges and universities such as Fisk, Morehouse, Dillard, and others. Eager to exercise autonomy, freedmen swarmed out of white churches and organized their own. Some affiliated with black denominations of northern origin; others formed their own southern associations.

Black ministers actively campaigned in Reconstruction politics and in some cases were elected to positions of influence and power. Richard H. Cain, for example, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from North Carolina and Hiram R. Revels was elected to the Senate from Mississippi. With the failure of Reconstruction and the disfranchisement of black southerners, the church once again became the sole forum for black politics, as well as the economic, social, and educational center of black communities across the South.

By the end of the century, black church membership stood at an astounding 2.7 million out of a population of 8.3 million. Most numerous were the Baptists, who succeeded in 1895 in creating a National Baptist Convention, followed numerically by the black Methodists, as institutionalized in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, both founded in the North early in the century, and the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, formed by an amicable withdrawal from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, in 1870.

Though too poor to mount a full-fledged missionary campaign, the black churches turned to evangelization of Africa as a challenge to Afro-American Christian identity. The first black missionaries, David George and George Liele, had sailed during the Revolution, George to Nova Scotia and then to Sierra Leone, Liele to Jamaica. Daniel Coker followed in 1820 and Lott Carey and Colin Teague in 1821. But in the 1870s and 1880s, the mission to Africa seemed all the more urgent. As race relations worsened, as lynching mounted in frequency, as racism was legislated in Jim Crow statutes, emigration appeared to black clergy like Henry McNeal Turner to be the only solution. Others saw the redemption of Africa as the divinely appointed destiny of black Americans, God’s plan for drawing good out of the evil of slavery and oppression.

Connections between southern black churches and northern ones developed as blacks from the South migrated or escaped north and as northern missionaries came to the South after the Civil War. Several southern blacks assumed positions of leadership in northern churches. Josiah Bishop, a Baptist preacher from Virginia, became pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, and Daniel Alexander Payne and Morris Brown, both of Charleston, became bishops of the AME Church. Beginning in the 1890s and increasing after the turn of the century, rural southern blacks migrated in larger and larger numbers to the cities of the North. Frequently, their ministers traveled with them and transplanted, often in storefront or house churches, congregations from the South.

In the cities, southern as well as northern, black migrants encountered new religious options that attracted some adherents from the traditional churches. Catholicism, through the influence of parochial schools, began attracting significant numbers of blacks in the 20th century. Black Muslims and Jews developed new religioracial identities for African Americans disillusioned with Christianity. The Holiness and Pentecostal churches stressed the experiential and ecstatic dimensions of worship while preaching the necessity of sanctification and the blessings of the Spirit. They also facilitated the development of gospel music by allowing the use of instruments and secular tunes in church services.

Though urbanization and secularization led to criticism of black religion as accommodationist and compensatory, the church remained the most important and effective public institution in southern black life. The religious culture of the black folk was celebrated by intellectuals like W. E. B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, who acclaimed the artistry of the slave spirituals and black preaching.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, the civil rights movement drew heavily upon the institutional and ethical resources of the black churches across the South. Martin Luther King Jr. brought to the attention of the nation and the world the moral tradition of black religion. Today, black religion is more pluralistic than ever. Most African Americans continue to worship in predominantly black denominations, although they also form identifiable caucuses with biracial denominations. Black liberation theology associated with southern-born writers like James Cone and Pauli Murray has been an influence on some of the faithful for decades. Roman Catholics and Muslims include significant communities of African Americans in the South. Black religious leaders and laypeople continue to work for racial justice and to cooperate in racial reconciliation efforts in the South. Churches remain important political organizing sites and encourage political participation among their members. Although the church is no longer the only institution that blacks control, it still exerts considerable power in black communities.

ALBERT J. RABOTEAU

Princeton University

Hans A. Baer, The Black Spiritual Movement: A Religious Response to Racism (1984); Yvonne Chireau, Black Magic: Dimensions of the Supernatural in African American Religion (2000); James Cone, For My People: Black Theology and the Black Church (1984); W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903); Sylvia R. Frey and Betty Wood, Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830 (1998); Samuel S. Hill, ed., Religion in the Southern States: A Historical Study (1983); C. Eric Lincoln, ed., The Black Experience in Religion (1974); Donald G. Mathews, Religion in the Old South (1977); William E. Montgomery, Under Their Own Vine and Fig Tree: The African American Church in the South, 1865–1900 (1993); Albert J. Raboteau, Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans (1999), Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (1978); Clarence Walker, A Rock in a Weary Land: The African Methodist Episcopal Church during the Civil War and Reconstruction (1982); James M. Washington, Frustrated Fellowship: The Black Baptist Quest for Social Power (1986); Joseph R. Washington, Black Religion: The Negro and Christianity in the United States (1964).

Religion, Latino

Specific forms of Latino Catholicism have a long historical trajectory in the geographic extremes of the South, but in the past decade Latino religion has become increasingly pervasive and varied throughout the region. Tejano (Mexican Texan) religion dates back to Mexico’s ceding of Texas to the United States, which was completed with the Compromise of 1850. In the late 19th century, mestizos in the region, whose indigenous ancestors had been evangelized by Franciscans during Spanish military expeditions, identified as Catholic but had tenuous ties to the institutional church. As the U.S. Catholic Church assumed ecclesiastical control of the region, many factors hindered Tejano participation in the church: only a handful of functioning parishes already existed in the region; Tejanos had a long history of anticlericalism, which resulted from the Catholic Church’s alignment with Spain against Mexican independence; and as Anglo-American clergy arrived in Texas, most brought with them a strong bias against Mexican Texans, with a few notable exceptions (such as the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who worked extensively with Tejanos in the south Texas borderlands). Nevertheless, many Tejanos practiced a vibrant home-centered religion that revolved around devotions to Mary and the saints, as well as a range of syncretic practices such as curanderismo, a blend of Catholicism with ancient Mesoamerican healing rites that continues to thrive among Mexicans in the South.

Between 1910 and 1940, Tejanos were joined by hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants, who had been pushed from the interior of Mexico by the Mexican Revolution (1910–19) and the Cristero Rebellion (1926–29). The new Mexican government’s persecution of the Catholic Church and popular revolts in support of the clergy resulted in the exile of Catholic faithful, nuns, and priests. Once in Texas, these exiles worked together to build their own churches, parochial schools, and service centers. Nevertheless, many remained underserved by Catholic diocesan structures, which remained focused on “Anglo” (non-Mexican) Catholics. In some regions of Texas, religious (order) priests were given the responsibility of ministering to Mexicans in separate churches. In 1954, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate constructed a large shrine in the Lower Rio Grande Valley to honor the Virgin of San Juan, to whom many Mexican immigrants in the area had a powerful devotion. Currently, almost 1 million visitors pass through the doors of the Shrine of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle annually, making it the most visited Catholic pilgrimage destination in the United States.

As Texas was beginning its secession from Mexico, another form of Latino popular religiosity was establishing a presence in the South: that of Cuban immigrants to Florida. The first Florida Cuban communities formed in Key West in 1831 and Ybor City, Tampa, in 1886. Both of these communities were made up of cigar makers and their families, who were supporters of Cuban independence from Spain and of José Martí’s Partido Revolucionario Cubano. As in Mexico, support of the revolution was generally accompanied by a strong dose of anticlericalism, since the Cuban Catholic Church aligned with Spanish colonial powers. Nevertheless, Ybor City’s first Catholic church was established by a Jesuit priest in 1890, and a second Cuban parish opened in 1922. Although the Catholic Church was widely regarded as a weak and relatively insignificant institution in Ybor City, some evidence exists that home-based popular religiosity and African-based syncretic religious practices thrived there.

In 1961, as a result of the Cuban Revolution, two-thirds of the Catholic clergy of Cuba were evicted, and they were accompanied by almost 80,000 anti-Communist exiles. These exiles, and hundreds of thousands more in the years to come, took refuge in the primarily Protestant, typically southern city of Miami. With the help of exiled clergy, they quickly set about re-creating some of their religious institutions, including numerous Catholic schools and student associations, in Miami. Unlike their Mexican counterparts in Texas earlier in the century, they also encountered a Catholic diocese that was eager to assist them, provided a wide range of material resources, and expected them to rapidly and fully assimilate into already existing “American” parishes. In 1966, perhaps to temper well-documented Cuban Catholic resistance to this plan for assimilation, the bishop of Miami established a shrine for Our Lady of Charity, Cuba’s patroness. This sacred site annually attracts hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, making it the sixth-largest Catholic pilgrimage site in the United States.

Currently, the south Florida Shrine of Our Lady of Charity and the south Texas Shrine of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle anchor Latino religion in the South. Both popular pilgrimage destinations juxtapose Cuban or Mexican nationalism with tensions between heterodox and orthodox Catholicism, since they are inevitably sites for practices associated with Santeria and curanderismo, respectively. Santeria has steadily grown in popularity in Miami as a result of both the Mariel boatlift in the early 1980s, which brought proportionally more practitioners of Afro-Cuban religions than earlier migrations, and U.S. Supreme Court proceedings of 1993, which increased the status and publicity of Santeria in the United States. Such practices receive strong disapproval and are often dismissed as “superstition” or worse by the Catholic hierarchy, which uses the popular shrines to evangelize Latinos, encouraging them to practice a more orthodox and church-centered Catholicism.

In the past decade, the exponential growth of the Latino population in the traditional Bible Belt has meant that Latino religion is no longer confined to the South’s geographic extremes. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, six of the seven states that have experienced a more than 200 percent increase in Hispanic population since 1990 are located in the historically “Baptist South” (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas). Two of the states in which this increase has been most profound are Georgia and North Carolina, where the foreign-born population has exploded as a result of changing migration patterns of Mexicans and the increasing presence of immigrants from throughout Central and South America, particularly Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Colombia, and Peru. What constitutes contemporary “Latino religion” in these states is, in fact, the religion of very recent Latin American immigrants, most of whom are young, mobile, and undocumented residents of the United States. Many can also be characterized as transmigrants, because they maintain close ties to their places of origin. Such ties are often religiously mediated through Catholic activities like feast-day celebrations for local, regional, and national saints or through the connections that evangelical and Pentecostal churches have to parent organizations in their members’ places of origin.

As they reshape the religious contours of these southern states, new immigrants radically impact the presence and role of the Catholic Church, change the traditional mission fields for established Protestant churches, and introduce a range of new religious practices and organizations. Georgia and North Carolina are home to four of the six Catholic dioceses in the United States with the fastest-growing Hispanic membership (Charlotte, Atlanta, Raleigh, and Savannah). Currently, 46 percent of the churches in the Archdiocese of Atlanta offer Spanish masses, and the Diocese of Raleigh offers such masses in 61 percent of its churches. Beyond offering mass, the Catholic Church is struggling to respond appropriately to these newcomers and defend against what it perceives to be the dangerous lure of Pentecostal and evangelical churches. The most popular strategies used by the Catholic Church to be more inviting to Latinos and counteract the appeal of Protestant churches are to offer a broad range of social services and to establish charismatic worship groups.

There are two primary sources of Latino Protestant congregations in the South. The first, and less prevalent, type results from a perceptible shift in the home mission field of well-established denominations. An association of Hispanic Baptists in Georgia, for instance, now includes more than 70 congregations, many of which are associated with the Southern Baptist Convention. In Georgia and North Carolina, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Methodists, and Presbyterians have all worked to establish Latino congregations, often recruiting Latino clergy from other parts of the United States, but they have been less successful than their Baptist counterparts. Baptist churches offer less arduous routes to both ordination and the formation of new congregations, and non-Catholic Latino churches in the South appear more likely to thrive when they are independent and pastored by Latino newcomers. The second, and more prevalent, type of Latino Protestant congregation in the region is an extremely heterogeneous collection of small evangelical and Pentecostal groups that are unaffiliated with an established denomination in the region and pastored by Latin American immigrants. Interestingly, some such churches, such as Iglesia de Cristo Ministerios Elim, or La Luz del Mundo, have been brought with migrants from Guatemala and Mexico, respectively, to the South.

Home-based popular Catholicism continues to be the most pervasive (and varied) form of Latino religiosity in the South. Most recent Latin American immigrants to the region, like their predecessors, practice a religion that does not necessitate regular participation in particular churches. However, for many immigrants, religious organizations have assumed another kind of responsibility. In many parts of the South, Latino immigrants have sometimes arrived in unwelcoming, predominantly white destinations. Even when not resistant to their presence, southern cities and towns offer few, if any, services, advocacy groups, or even public gathering places for Latinos. In some such places, churches fill all of these roles, becoming sites for the defense and protection of undocumented immigrants, in particular. As they strive to provide much more than spiritual assistance to a minority group experiencing persecution and discrimination, these Latino religious organizations follow a route paved by African Americans in the South, along which churches become, for marginalized groups, centers of economic, social, educational, and political life.

MARIE FRIEDMANN MARQUARDT

Emory University

Gilberto M. Hinojosa, in Mexican Americans and the Catholic Church, 1900–1965, ed. Jay P. Dolan and Gilberto M. Hinojosa (1994); James Talmadge Moore, Through Fire and Flood: The Catholic Church in Frontier Texas, 1836–1900 (1992); Lisandro Pérez, in Puerto Rican and Cuban Catholics in the U.S., 1900–1965, ed. Jay P. Dolan and Jaime R. Vidal (1994); Thomas A. Tweed, Our Lady of the Exile: Diasporic Religion at a Cuban Catholic Shrine in Miami (1997), Southern Cultures (Summer 2002); Manuel A. Vasquez and Marie Friedmann Marquardt, Globalizing the Sacred: Religion across the Americas (2003); Martha Woodson Rees and T. Danyael Miller, Quienes Somos? Que Necesitamos? Needs Assessment of Hispanics in the Archdiocese of Atlanta (25 March 2002).

Religion, Native American

For millennia, religious practices enabled Native Americans in the Southeast to maintain or restore vital balances disrupted by human action or the actions of other living beings. Across the Southeast, Native Americans perceived spiritual values and meanings in a wide range of activities, events, and phenomena. They found holiness in a comet’s sweep across the sky, the earth’s rumbling in a quake, turbulence in a river, and the flight of a bird. Their dreams foretold the future, warning of impending sickness and death, or, more auspiciously, a successful hunt. Their systems of belief and morality shaped how they understood weather, birth, courtship, healing, death, horticulture, warfare, and diplomacy. Their pottery, baskets, clothing, jewelry, stories, place-names, art, and architecture invoked creation stories, mythic beings, and cosmic symbols. Their sacred sites, holy times, and festivals embodied their distinctive spiritual orientations toward the world.

Embedded so deeply in daily life and diffused so widely across so many activities, Native American religions were very influential, but ironically, they were to some extent invisible as religion. Many Native peoples did not think of religion as a separate thing or coin a word to name it. On the other hand, if there was not a well-bounded or tightly circumscribed phenomenon called “religion” in ancestral Native America, there were among many peoples special ceremonies, sacred buildings, and ritual specialists that stood out, possessed special names, and evoked extraordinary treatment. This was especially the case in nonegalitarian social formations, such as the Mississippian society that flourished 1,000 years ago along that river and to the east.