French

Francophone populations, though usually neglected in recounting the history and development of the South, have nonetheless played a prominent role, exemplifying ethnic-racial complexities. The first settlers in North America seeking refuge for religious reasons were not the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock in 1620, but French Huguenots in 1562 at coastal Charlefort (sometimes also called Charlesfort), located in what is now South Carolina. Because of privation and Spanish aggression, the settlement at Charlefort did not last long, but toward the end of the 17th century hundreds more Huguenots became part of the founding population of South Carolina, especially in Charleston. Many of their progeny grew wealthy, and indeed for a time Charleston rivaled every other colonial city on the Atlantic Coast for affluence, because of the extensive development of slave-based rice plantations. Despite sporadic testimonies of the subsequent survival of French, it appears that these prominent Huguenots (the most famous among them being “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion) assimilated rather quickly to the English language that predominated in the surrounding colonial setting. Much more for the sake of tradition than for linguistic necessity, the Huguenot Church at the corner of Church and Queen streets in Charleston still conducts an occasional service in French according to the 18th-century liturgy of les Eglises de la Principauté de Neuchâtel et Valangin.

Though Charleston is unrivaled in Old South tradition, its French Quarter cannot contend with the French Quarter of New Orleans, La., as the leading French-related cultural icon of the South. Indeed, the best-known and longest-surviving Francophone population in the South—and, until recently, the largest—has been located in Louisiana and its environs since the early 18th century. Robert Cavelier de La Salle descended the Mississippi from New France to its mouth in 1682 and claimed the entire Mississippi Valley and its tributaries for Louis XIV of France (hence, la Louisiane). Soon after, French settlements, or posts, were founded at Biloxi (1699), Mobile (1701), Natchitoches (1714), and La Nouvelle Orléans (1718). The varieties of French from the founding of Louisiana up to the present time form a complex picture, much of which is still speculative. Records clearly attest that French was the language of the colonial administrators, and some form of “popular French” was certainly in wide use. However, French was probably not the first language of many early colonists, who would have spoken a regional patois of France or who were often recruited from Germany or Switzerland. Moreover, communication with early indigenous peoples took place through a regional lingua franca, Mobilian Jargon, which served as a trade language and the language of diplomacy rather than French. It is noteworthy that very few French borrowings penetrated into the indigenous languages of the Southeast, such as the language of the Choctaw, with whom the French had a strong and long-standing military alliance.

The largest single population of French speakers to arrive in Louisiana during the colonial period did not come directly from France. French colonists who left the west central provinces of France and arrived in the early 17th century in Acadia (modern Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) were expelled from there by the British in 1755. Between 1765 and 1785, approximately 3,000 of them migrated to Louisiana (under Spanish administration from 1763) and occupied arable land principally along the bayous of southeastern Louisiana and the prairies of south-central Louisiana. This prolific population was destined to become the standard-bearer for maintaining French in Louisiana to the present day.

During the Spanish administration, the plantation economy of Louisiana began to blossom, dramatically affecting the French language there. On the one hand, the massive importation of slaves, coming directly from West Africa for the most part, apparently led to the formation of a French-based Creole language. Theories vary as to the genesis of Louisiana Creole, as it is usually referred to by scholars. The debate surrounding the origin of creole languages is complex, but, at the risk of oversimplifying, the two poles of opposition can be summed up here. Some scholars contend that creole languages were spontaneously generated on (large) plantations where slaves were linguistically heterogeneous and did not share a common tongue. According to this view, the structural parallels among creole languages are because of either linguistic universals or the interaction of a particular set of African and European languages. Others contend that most creole languages are simply daughter dialects of a pidgin associated with the slave trade, and though the lexicon can vary from one site to another owing to different vocabulary replacement, their basic structure remains the same. Regardless, Louisiana Creole became the native mode of communication within the slave population of Louisiana. Very frequently it was also the first language of the slave masters’ children, who were typically raised by domestic bondservants.

In tandem with this, the wealth of what was then known as the Creole society grew. Creole society is not to be confused with the entire population of Louisiana Creole speakers but is composed rather of the affluent European-origin planter class and also of mostly biracial Creoles of Color who held considerable social standing during the Spanish administration, sometimes being plantation owners themselves. Their considerable resources allowed for widespread schooling among Creoles and the resultant acquisition of the evolving prestige French of France, by virtue of boarding schools in France and Louisiana or by private tutoring. Referred to as Plantation Society French in recent scholarship, this brand of French has all but disappeared, in part because of the ruin of Creole society in the aftermath of the Civil War and the resultant severing of ties with France and in part because of the rather swift acquisition of English (even before the Civil War) by members of Creole society. English became economically and socially important under the new American administration, which brought a massive influx of Anglophones, both free and slave, into Louisiana after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Not all newcomers after 1803 were English speakers, however. Prior to the Civil War, the affluence of Louisiana attracted additional Francophone immigrants, often educated, whose ranks were swelled by defeated Bonapartistes banished from France and by planters (with their creolophone slaves in tow) fleeing the successful slave revolt in Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). Not all of the 19th-century newcomers settled in Louisiana: a group of Bonapartiste exiles founded Demopolis (in Alabama) in 1817, just prior to statehood.

Dependent on wealth generated by the plantation system and vulnerable to competition with the English for maintaining socioeconomic standing, once-prestigious Plantation Society French disappeared from use rather quickly. The vast majority of the agrarian, lower-class Acadian (or “Cajun”) population worked small farms and did not operate plantations (though some Acadians did gentrify and merge with creole society). Their autonomy and relative isolation led to a greater longevity for Cajun French. Significant numbers of immigrants (German, Irish, Italian, for example) in some places even assimilated to the use of Cajun French for a time. Meanwhile, Louisiana Creole was undergoing its demise, ultimately because of the breakup of the plantation system itself, but even before that because of the immense influx of Anglophone slaves during the 19th century when the importation of foreign slaves was prohibited, leading to massive importation of slaves from states farther east to meet the demand in booming Louisiana. Nevertheless, the social isolation of its speakers led Louisiana Creole to fare better than Plantation Society French, and today approximately 4,500 mostly elderly speakers remain, with the largest concentrations in Point Coupee and St. Martin parishes.

Acadiana, the 22-parish area where most Cajun French speakers still live, can be roughly described as a triangle whose apex is in Avoyelles Parish in the center of the state and whose base extends along the coast from eastern Texas to the Mississippi border. The Cajun French spoken there did not begin its demise until the 20th century, with the advent of compulsory schooling in English in 1916. This factor, coupled with better state infrastructure and accelerated exposure to mass media, eroded the social isolation of the Cajun population and led inexorably to assimilation to the English standard by younger ethnic Cajuns. Despite an important resurgence in Cajun pride since the late 1960s (the “Cajun Renaissance”) and attempts to bolster French in Louisiana, only the smallest fraction of children are now acquiring fluency in any variety of French. The few thousand who do so are not acquiring it in natural linguistic communities but primarily in French immersion programs in the public schools (introduced in 1968 when the state created the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana, CODOFIL, to reclaim French and promote bilingualism). Nevertheless, the Cajun Renaissance has spawned preservationist tendencies in some households, has resulted in a modicum of literary production by Cajun poets, playwrights, and storytellers, and is linked to the resurgence in popularity of Cajun music. Authenticity demands that Cajun musicians perform pieces in French and that even young songsmiths compose a portion of their newest lyrics in Cajun French.

Census figures for 2000 indicate a Francophone population of 194,100 for Louisiana. Even adding the creolophone population (4,685 in 2000) to that figure, the total fell far short of the combined French-speaking and creolophone populations of Florida in 2000 (125,650 + 211,950 = 337,600). Though European immigrants must also be taken into consideration, Florida is the new front-runner in the South, primarily because of its large number of French Canadian “snowbirds” and recent Haitian refugees. The Canadians, though elderly, represent a sustainable population as long as Florida remains an attractive retirement location, whereas the mostly elderly Francophone population of Louisiana is not self-replacing, except in a very small minority of cases where grandchildren are being reintroduced to French in a conscious attempt to preserve a linguistic legacy.

A description of the salient features of Cajun French and Louisiana Creole must take into account archaisms harking back to the French of the colonizers as well as innovations resulting from isolation and contact with other languages, especially English. For example, in various vocabulary items such as haut ‘high’ and happer ‘to seize’, both Cajun French and Louisiana Creole preserve the archaic pronunciation of the initial h, whereas the initial h has fallen silent in the contemporary French of France. At the grammatical level, both Cajun French and Louisiana Creole preserve the progressive modal après (sometimes apé or ap) of western regional France, denoting an ongoing action—for example, je sus après jongler ‘I’m thinking’ (Cajun French) or m’apé fatigué ‘I’m getting tired’ (Louisiana Creole). This usage is entirely absent in the standard French of France. Concerning innovations, historic contact with indigenous languages has enriched the vocabularies of French dialects in Louisiana with words such as chaoui ‘raccoon’ and bayou (subsequently borrowed into English). Contact with dominant English has had a profound impact on both Cajun French and Louisiana Creole. Assimilated borrowings are easy to find (récorder ‘to record’), but because of near-universal bilingualism among Cajun French speakers and creolophones in Louisiana, it is even more common to hear the insertion of English vocabulary items into French or creole conversation: j’ai RIDE dessus le BIKE ‘I rode the bike.’ Imitative calques of English phrasing are also common, as in the case of a Cajun radio announcer reciting the standard expression apporté à vous-aut’ par ‘brought to you by.’

Though overlapping vocabularies are extensive, Louisiana Creole is distinct from Cajun French in a variety of ways. Of particular note in Louisiana Creole are a different system of pronouns, more frequent use of nouns that have permanently incorporated part or all of what were once preceding French articles, placement of the definite article after its noun, absence of linking verbs, absence of inflection on main verbs, and use of various particles to indicate tense. Compare the Louisiana Creole sentence yé té lave zonyon-yé ‘they washed the onions’ with ils ont lavé les oignons in Cajun French.

English in Louisiana dethroned Plantation Society French as the most highly valued idiom and may have temporarily protected nonstandard Louisiana Creole and Cajun French from absorption by prestigious standard French (such was the demise of patois and regional French in France). However, today English has become a formidable competitor, with the imminent prospect of supplanting all traditional varieties of Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole in the region where both thrived for over two-and-a-half centuries. Yet despite the demise of French as a first language in Louisiana, its influence remains noticeable in the spoken English of the region. Even in New Orleans, where the transition from French to English as the language of everyday communication has long been complete, vestiges of French can be found in colloquial calques such as get down ‘get out’ (of a vehicle) and borrowings such as banquette ‘sidewalk,’ parrain ‘godfather,’ and beignet (type of fried dough). This phenomenon is even more common in rural Cajun communities, where one hears French borrowings in remarks such as we were so honte (that is, ‘embarrassed’) and I have the envie (that is, ‘the desire’) for rice and gravy. Less common but still used are structural calques from French: Your hair’s too long. You need to cut ’em (hair as plural, corresponding in use to les cheveux) or That makes forty years we married (calqued from ça fait quarante ans qu’on est marié).

English is not the only force arrayed against the survival of French in Louisiana. In Plaquemines Parish, Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, decimated one of the few remaining non-Cajun Francophone enclaves, and ecological degradation, such as that which augmented the devastating effects of the storm, is contributing to the breakup of some of the more isolated Francophone communities (who mostly self-identify as Houma Indians) in Terrebonne Parish, where French has been best preserved among younger speakers.

MICHAEL D. PICONE

University of Alabama

AMANDA LAFLEUR

Louisiana State University

Barry Jean Ancelet, Cajun and Creole Folktales: The French Oral Tradition of South Louisiana (1994); Carl A. Brasseaux, French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana (2005); Marilyn J. Conwell and Alphonse Juilland, Louisiana French Grammar (1963); Thomas A. Klingler, If I Could Turn My Tongue Like That: TheCreole Language of Pointe Coupee, Louisiana (2003); Kevin J. Rottet, Language Shift in the Coastal Marshes of Louisiana (2001); Albert Valdman, ed., French and Creole in Louisiana (1997).

Hurston, Zora Neale

(ca. 1901–1960) WRITER AND FOLKLORIST.

Born in either 1891 or 1901—the latter is normally given as the date of birth but recent studies suggest an earlier date—in the all-black town of Eatonville, Fla., Zora Neale Hurston became a distinguished novelist, folklorist, and anthropologist. She was next to the youngest of eight children, born the daughter of a Baptist minister who was mayor of Eatonville. Her mother died when Hurston was 9, and she left home at 14 to join a traveling show. She later attended Howard University, where she studied under Alain Locke and Lorenzo Dow Turner, and she earned an A.B. degree from Barnard College in 1928, working with Franz Boas. She became a well-known figure among the New York intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance in the mid-1920s and then devoted the years 1927 to 1932 to field research in Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and the Bahamas. Mules and Men (1935) was a collection of black music, games, oral lore, and religious practices. Tell My Horse (1938) was a similar collection of folklore from Jamaica and Haiti.

Hurston published four novels—Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934), Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939), and Seraph on the Sewanee (1948). Her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, appeared in 1948. Married and divorced twice, she worked for the WPA Federal Theatre Project in New York (1935–36) and for the Federal Writers’ Project in Florida (1938). She taught briefly at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Fla. (1934), and at North Carolina College in Durham (1939), and she received Rosenwald and Guggenheim fellowships (1934, 1936–37).

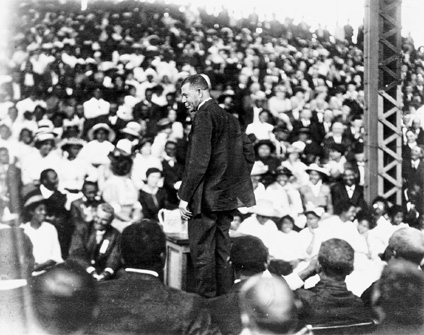

Zora Neale Hurston, a distinguished novelist, folklorist, and anthropologist who was noteworthy for her portrayal of the strength of black life in the South. (Photo by Carl Van Vechten, 1938)

In her essay “The Pet Negro System,” Hurston assured her readers that not all black southerners fit the illiterate sharecropper stereotype fostered by the northern media. She pointed to the seldom-noted black professionals who, like herself, remained in the South because they liked some things about it. Most educated blacks, Hurston insisted, preferred not to live up North because they came to realize that there was “segregation and discrimination up there, too, with none of the human touches of the South.” One of the “human touches” to which Hurston referred was the “pet Negro system” itself, a southern practice that afforded special privileges to blacks who met standards set by their white benefactors. The system survived, she said, because it reinforced the white southerner’s sense of superiority. Clearly, it was not a desirable substitute for social, economic, and political equality, but Hurston’s portrayal of the system indicated her affirmative attitude toward the region, despite its dubious customs.

Hurston had faith in individual initiative, confidence in the strength of black culture, and strong trust in the ultimate goodwill of southern white people, all of which influenced her perceptions of significant racial issues. When she saw blacks suffering hardships, she refused to acknowledge that racism was a major contributing factor, probably because she never let racism stop her. Hurston’s biographer, Robert E. Hemenway, notes that “in her later life she came to interpret all attempts to emphasize black suffering . . . as the politics of deprivation, implying a tragedy of color in Afro-American life.”

After working for years as a maid in Miami, Hurston suffered a stroke in early 1959 and, alone and indigent, died in the Saint Lucie County Welfare Home, Fort Pierce, Fla., on 28 January 1960. Alice Walker led a “rediscovery” of Hurston, whose works have become inspiration for black women writers.

ELVIN HOLT

University of Kentucky

Valerie Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston (2002); Robert E. Hemenway, Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (1977); Zora Neale Hurston, I Love Myself, ed. Alice Walker (1979); Carla Kaplan, ed., Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (2002); Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983).

Japanese American Incarceration during World War II

Following decades of racial prejudice, combined with economic envy and sexual anxiety over miscegenation and nationality, 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II were indiscriminately subjected to eviction from their homes, expulsion from the West Coast, detention in 16 makeshift compounds, and then concentration into 10 longer-term camps. Empowered by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 of 19 February 1942, military and civilian officials carried out these constitutionally dubious procedures with guns and euphemism. The forced migrations were called, in turn, “evacuation,” implying rescue; “removal,” suggesting it was voluntary; “assembly,” a purported freedom; and “relocation,” a mere transfer.

However, after a grueling four-day train journey, blinds down, Americans of Japanese descent arriving at the two camps in southeast Arkansas expected no relief. Disembarking, they saw guard towers, barbed wire fencing, and—at both camps—nearly a square mile of barracks. Previously referred to by their dehumanizing family numbers, attached to clothing and suitcases, they now would be known by their three-part address: block and building number and the letter of their one-room apartment, none more than 20 by 24 feet. Ever after, Japanese Americans would remember where they or their ancestors had been incarcerated during the war. Here, near the banks of the Mississippi, in rural Chicot and Desha counties, respectively, it was the Jerome and Rohwer camps.

With peak populations of 8,500 each, Jerome and Rohwer brought together captives from southern California and the Central Valley, along with white staffers, mostly Arkansans. They worked side by side in similar jobs, as teachers and legal professionals, for example, but at a fraction of the pay for the former. Still, Japanese American women, less tied to onerous domestic duties, worked at the same rates as Japanese American men, enjoying unexpected autonomy. Most jobs were voluntary, though boys and men were forced into hazardous logging and woodcutting operations for winter fuel, resulting in dozens of injuries and at least three deaths. Labor unrest was characterized by strikes and harsh administration crackdowns, especially at Jerome. Inmates were targeted for indoctrination, through so-called Americanization campaigns in the schools and adult classes. The largely Buddhist population endured aggressive Protestant revivals.

English-speaking Christians gained special privileges, including greater freedom of movement. Leave was selectively granted for temporary work contracts outside the camps and for college education. Japanese Americans enrolled at otherwise segregated southern campuses, including elite private universities such as Emory, Rice, Tulane, and Vanderbilt and flagship state universities in Florida, North Carolina, and Texas, among others. From all 10 camps and from the Territory of Hawaii, thousands volunteered—more were later drafted—for military service in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which trained at Camp Shelby in Mississippi. Though segregated into their own units and barracks, the 442nd competed in “white” rather than “colored” sports leagues, at Shelby and across the South. Generally under local biracial structures of Jim Crow, authorities encouraged soldiers, students, contract laborers, and day-pass holders to use white facilities and to frequent white establishments. Many of these establishments turned them away.

At the same time, officials conspired to delimit Japanese American interaction with whites and with blacks. Interracial dating and marriage were particularly proscribed, and given the segregation of USO clubs around Camp Shelby, Japanese American women at Jerome and Rohwer were regularly bussed 250 miles for dances with the 442nd. Leave was denied to inmates with job offers from black schools and businesses. When black agricultural workers took collective action against local planters, these labor hotspots were declared off-limits to Japanese Americans. Though sometimes joining African Americans, as a matter of principle, in the back of the bus, Japanese Americans more commonly sought and occasionally secured the benefits of higher status, even blacking up with their white captors for camp minstrel shows.

When government agencies finally attempted to ascertain individual allegiance, rather than assuming collective guilt, Japanese American discontent hardened. Across all 10 camps in the West and the South, an ill-conceived, ill-administered loyalty questionnaire both confounded and enraged prisoners. And at higher percentages than at any other camp, Jerome protesters were reassigned to the Tule Lake camp in California, reconfigured as an isolation center. Among them was Tokio Yamane, who in sworn testimony to Congress described officers torturing him and others there. Yamane and hundreds more renounced their American citizenship and moved to Japan. No Japanese American was ever convicted of espionage.

Though resilient and productive, growing almost all their own food and sourcing other essentials through an innovative system of cooperative stores, Japanese Americans in Arkansas experienced yet another wrenching upheaval. Called “resettlement” by authorities, the closing of the camps involved a calculated dispersal of Japanese Americans in order to break up prewar ethnic enclaves: a massive population redistribution from west to east. Arkansas inmates proposed converting Jerome and Rohwer into agrarian cooperative colonies, given their marked improvements to local infrastructure. Instead, the government sold it all and kicked them out. Just as early in the incarceration a despairing John Yoshida committed suicide at the railroad tracks near Jerome—haunting photos of his decapitated body lingering in the archives—so too in the wake of Hiroshima, ancestral prefecture to the largest number of Japanese Americans, did Julia Dakuzaku take her life after release from Arkansas.

The most cynical euphemism of all, persisting to this day, “internment” is a concept recognized in international law for the wartime detention of “enemy aliens,” citizens of combatant nations. The vast majority—over 70 percent—of the 120,000 people imprisoned in American concentration camps were birthright U.S. citizens; the remaining 30 percent were decades-long residents who were forbidden naturalization. Though these Americans of Japanese descent advocated for and eventually won restitution as partial recompense for loss of income and property, the United States has never accepted responsibility for loss of life.

JOHN HOWARD

King’s College London

Roger Daniels, in Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century, ed. Louis Fiset and Gail M. Nomura (2005); John Howard, Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow (2008); Emily Roxworthy and Amit Chourasia, Drama in the Delta: Digitally Reenacting Civil Rights Performances at Arkansas’ Wartime Camps for Japanese Americans, www.dramainthedelta.com; Jason Morgan Ward, Journal of Southern History (February 2007).

Jazz

Jazz can be defined by its musical elements, such as improvisation, syncopation, blue notes, cyclical forms, and rhythmic contrasts, but also through its place in the social, economic, and cultural history of the United States. The subject of its racial identity has proved particularly thorny for musicians, critics, and audiences, for despite the diversity of jazz styles and performers, it is rooted in African American musical traditions at the turn of the 20th century. The tension between its aesthetic breadth and racial specificity has long animated debates regarding ownership, politics, and history. Rather than simplifying matters, its New Orleans origins demonstrate that the birth of jazz was enmeshed in the historical development of modern African American identity and culture.

Among the most prosperous and populous cities in the antebellum South—central to both international commerce and the domestic slave trade—19th-century New Orleans was musically and culturally rich. Contemporaries noted with wonder the proliferation of opera houses, orchestras, parades, and carnivals, as well as the slaves and free blacks who gathered at Congo Square on Sundays to dance and perform. With the end of American slavery, waves of freedpeople left the rural South. They brought with them African-influenced musical traditions, including spirituals and field songs as well as instrumental bands and arrangements formed in the lower Mississippi Delta. By the end of the 19th century, the city was an amalgam of English, French, and Spanish cultures, but its structure was soon transformed in the wake of Jim Crow racial codes spreading throughout the South. Caribbean Creoles, or gens de couleur, had previously held significant political and economic power as an intermediate group between white Europeans and blacks. However, with the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy decision to uphold the separate-but-equal statute, the situation changed. Longtime Creole residents and recent black migrants, who continued to enter the city in ever-greater numbers seeking employment, found themselves on the same side of a stricter color line.

While Jim Crow was racially redefining many of its pioneers and performers, the musical components of jazz came together in New Orleans. It is difficult to know what early jazz sounded like without recorded documentation, but scholars believe that fundamental transformations in the form and instrumentation of popular music occurred between 1900 and 1910. Hoping to fill a dance hall, attract a crowd, or enliven a march, Uptown blacks and Downtown Creole musicians crossed previous social and geographic divides. They found new techniques and instrumentations in the various quarters of New Orleans and transformed well-known arrangements and popular songs by syncopating instrumental parts, improvising melodies over marchlike rhythms, and adding melodic strains and blue notes. Musicians drew on a diverse repertory, which included ragtime, marches, blues, popular songs, dance music, Spanish Caribbean music, and spirituals. They played in brass bands and in smaller ensembles made up of a rhythm section—drums, piano, banjo, bass, tuba—and a lead section, which could include a clarinet, trumpet, cornet, or trombone. While this new sound was associated with saloons in the red-light district of Storyville, groups like the Golden Rule and the Eagle played at store openings, parades, picnics, funerals, and balls. Bandleaders such as Buddy Bolden, Manuel Perez, Nick LaRocca, and Kid Ory cultivated a dense and competitive musical environment that circulated new rhythmic and melodic styles. Many of the soloists known for the New Orleans jazz style, like Joe “King” Oliver, Bunk Johnson, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and Sidney Bechet, trained within an all-male environment that valued individual technique as well as ensemble arrangements and fraternal support.

Through itinerant musicians and expanding transportation networks, many of the identifiable musical precedents of jazz continued to develop on their own beyond New Orleans. In St. Louis, ragtime and blues formed the root of a distinctive boogie-woogie piano-playing style. Meanwhile, the Kansas City style achieved national recognition through musicians like Count Basie and Mary Lou Williams. The development of jazz was further aided by the large-scale migration of African Americans that began at the turn of the century. Like other black Americans who left the South, jazz musicians sought work in Chicago, New York, and California, where they found new audiences but maintained southern professional networks. The migration was accompanied by major advances in radio and recording technology that in turn made jazz a national and international music. White New Orleans musicians in the Original Dixieland Jazz Band made the first jazz recordings, but soon black southerners, including Oliver and Armstrong, were putting out records and touring Europe. As jazz gained global recognition, the American South remained an important cultural symbol. Jazz enthusiasts in the 1920s flocked to New York’s Cotton Club and Chicago’s Plantation Club, where racial stereotypes of the South were reproduced for urban audiences in the North. In the 1930s, the revival of the Dixieland style represented authenticity in the face of the rising popularity of big band arrangements. The South also remained politically important for many musicians. A wide range of performers supported the southern civil rights movement by fund-raising for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), speaking out against civil rights abuses, and creating music, like Max Roach’s 1960 We Insist! The Freedom Now Suite. From its origins to contemporary efforts at preservation, the South has been a site of opportunity and struggle for jazz musicians, shaping the roots of this racially defined yet culturally cosmopolitan music.

CELESTE DAY MOORE

University of Chicago

David Ake, Jazz Cultures (2002); Sidney Bechet, Treat It Gentle (1960); Charles B. Hersch, Subversive Sounds: Race and the Birth of Jazz in New Orleans (2007); William H. Kenney, Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History, 1904–1930 (1993); Ingrid Monson, Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Call Out to Jazz and Africa (2007); Jelly Roll Morton, Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax (1938); Burton Peretti, The Creation of Jazz: Music, Race, and Culture in Urban America (1992); Eric Porter, What Is This Thing Called Jazz? African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists (2002).

King, Martin Luther, Jr.

(1929–1968) CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER.

Born into a middle-class black family in Atlanta, Ga., on 15 January 1929, Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as the key figure in the civil rights crusade that transformed the American South in the 1950s and 1960s. As a student at Atlanta’s Morehouse College (1944–48), he majored in sociology and developed an intense interest in the behavior of social groups and the economic and cultural arrangements of southern society. King’s education continued at Crozer Theological Seminary (1948–51) and Boston University (1951–55), where he studied trends in liberal Christian theology, philosophy, and ethics, while also engaging in an intellectual quest for a method to eliminate social evil. With a seminary degree and a Ph.D. from Boston, King lived remarkably free of material concerns and personified the intellectual-activist type that constituted the principal model for W. E. B. Du Bois’s talented-tenth leadership theory.

Although mindful of how poverty and economic injustice victimized both races in the South in his time, King understood the social stratification of the region largely in terms of the basic distinctions between powerful whites and powerless Negroes. Framing the struggle as essentially a clash between loveless power and powerless love, King rose to prominence in the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955–56, and he and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) later led nonviolent direct-action campaigns for equal rights and social justice in Albany, Birmingham, St. Augustine, Selma, and other southern towns. King’s celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington on 28 August 1963 firmly established him as the most powerful leader of the black freedom struggle.

After receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, King moved toward a more enlightened and explicit globalism. Convinced that the struggle for basic civil and/or constitutional rights had been won with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he turned more consciously toward economic justice and international peace issues. He saw the interconnectedness of racial oppression, class exploitation, and militarism and moved beyond integrated buses, lunch counters, and schools for blacks to highlight the need for basic structural changes within the capitalistic system. He recognized that economic justice was a more complex and costlier matter than civil rights and that poverty and economic powerlessness afflicted both people of color and whites. He prophetically critiqued the wealth and power of the white American elites and chided the black middle class for its neglect of and indifference toward what he labeled “the least of these.” King also fought for the elimination of slum conditions in Chicago in 1965–66, launched a Poor People’s Campaign in 1967, and participated in the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike in early 1968. His attacks on capitalism, his call for a radical redistribution of economic power, his assault on poverty and economic injustice in the so-called Third World, and his cry against his nation’s misadventure in Vietnam were all aimed at the same structures of systemic social evil. King framed his vision in terms of the metaphors of “New South,” “American Dream,” and “World House,” all of which embodied what he considered the highest human and ethical ideal, namely, the beloved community, or a completely integrated society and world based on love, justice, human dignity, and peace.

Martin Luther King Jr. (in hat) and Stokely Carmichael (right) during civil rights march in Coldwater, Miss., 1966 (Ernest C. Withers, photographer, Memphis, Tenn.)

King’s broadened social vision can be understood in terms of democratic socialism and the tactics of massive civil disobedience and nonviolent sabotage that he thought would be required to achieve this ideal. While traveling to Oslo, Norway, to receive the Nobel Prize, he saw democratic socialism at work in the Scandinavian countries. In King’s estimation, democratic socialism, which he considered more consistent with the Christian ethic than either capitalism or communism, would allow for the nationalization of basic industries, massive federal expenditures to enhance city centers and to provide employment for residents, a guaranteed income for every adult citizen, and universal education and health care, thus amounting to the kind of sweeping economic and structural changes essential for the creation of a more just, inclusive, and peaceful society.

King was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., on 4 April 1968, weeks before his planned Poor People’s Campaign was launched. Economic justice and international peace remain as the core issues in his unfinished holy crusade. In the half century since his death, some conservative forces have increasingly sought to use him as a kind of sacred aura for their own political ends, particularly in their attacks on affirmative action, immigration, reparations, and government spending for social programs.

LEWIS V. BALDWIN

Vanderbilt University

Lewis V. Baldwin, The Voice of Conscience: The Church in the Mind of Martin Luther King, Jr. (2010); Clayborne Carson, ed., The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1998); Kenneth L. Smith, Journal of Ecumenical Studies (Spring 1989); William D. Watley, Roots of Resistance: The Nonviolent Ethic of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1985).

Ku Klux Klan, Civil Rights Era to the Present

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) is the oldest documented white supremacist group in the United States. Historically, the KKK precipitated, engaged in, and supported numerous acts of intimidation and violence in the South. Bombings, murders, assaults, and other violent acts were sanctioned by the social norms of southern culture during a time in which KKK members were also employed in positions of power (for example, as sheriffs and judges). Their place in society contributed to the disproportionate enforcement, prosecution, and sentencing of whites who antagonized and victimized blacks and others in the South. Although the first two waves of KKK members benefited from a cohesive unit of organization, members of the third wave arose from dozens of independent groups that utilized the KKK moniker during the 1960s in resistance to the civil rights movement.

The rise of black freedom struggles in the 1950s provoked a massive resistance on the part of southern whites. The KKK reemerged as the most violent expression of this resistance. KKK members were implicated in a series of incidents, including the 1963 church bombing that killed four young girls, the 1963 assassination of NAACP organizer Medgar Evers, and the 1964 murder of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Miss. The nationwide media coverage of the aftermath of these violent incidents contributed to the KKKYou need to cuts increasingly unfavorable image outside the South.

During the 1970s and 1980s, racially motivated acts of violence perpetrated by KKK members did not cease entirely. For instance, in 1979, in what came to be known as the Greensboro Massacre, KKK members (in collaboration with Nazi Party members) murdered five protesters at an anti-Klan rally in Greensboro, N.C. In 1980, four older black women were shot after a KKK initiation rally in Chattanooga, Tenn. In 1981, Michael Donald became the last documented lynching in Alabama. Unlike earlier incidences in which cases were dismissed or offenders were acquitted by all-white juries, the perpetrators of these acts were criminally prosecuted for their crimes. In some instances, KKK organizations faced civil opposition, resulting in their financial collapse (for example, United Klans of America and Imperial Klans of America). The Southern Poverty Law Center’s founder, Morris Dees, led civil cases against these groups, and the U.S. government increased its oversight. These factors made it increasingly unacceptable for the KKK to resort to violence as a means to further its political agenda.

Today the Southern Poverty Law Center estimates that thousands of KKK members are split among at least 186 KKK chapters. These fragmented factions have been weakened by “internal conflicts, court cases, and government infiltration.” However, they still disseminate hate against blacks, Jews, Latinos, immigrants, homosexuals, and Catholics. Instead of violence, some of today’s KKK organizations focus on collective political action by participating in and restructuring the government. Others focus on marketing strategies in order to appeal to mainstream America, with the intention of increasing recruitment and disseminating their ideology to a wider audience. Although violent acts, like the 2008 murder of a woman in Louisiana after a failed KKK initiation, do still randomly occur, violence is no longer considered a socially accepted means to achieving white hegemony in the South.

STACIA GILLIARD-MATTHEWS

West Virginia University

Josh Adams and Vincent Roscigno, Social Forces (December 2005); Chip Berlet and Stanislav Vysotsky, Journal of Political and Military Sociology (Summer 2006); David Chalmers, Backfire: How the Ku Klux Klan Helped the Civil Rights Movement (2005), Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan (1987); David Holthouse, The Year in Hate (2009); Diane McWhorter, Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution (2001); Pete Simi and Robert Futrell, American Swastika: Inside the White Power Movement’s Hidden Spaces of Hate (2010).

Ku Klux Klan, Reconstruction-Era

The Ku Klux Klan was the name popularly given to hundreds of loosely connected vigilante groups that emerged in the early Reconstruction era in locations throughout the South. These groups used violence and threats, primarily against freedpeople, local white Republicans, immigrants from the North, and agents of the federal government, to gain political, social, cultural, and economic benefits in the wake of the war. Although some prominent figures attempted to organize the Klan and use it as political tool, the Klan was never effectively centralized. Klan groups proliferated rapidly in 1868 and saw a second peak in 1870–71. The Klan movement was in decline by late 1871 and had almost disappeared by the end of 1872.

The first group to call itself the Ku Klux Klan began in Pulaski, Tenn., probably in summer 1866. The six original members were young, small-town professionals and Confederate veterans. This group was at first fundamentally a social club. Members performed music and organized entertainments. Significantly, they also introduced a particularly elaborate version of the rituals and costumes common to fraternal associations.

As the Pulaski Klan spread, local elites became interested in its potential as a political organization in opposition to the government of Gov. William Gannaway Brownlow. In an April 1867 meeting in nearby Nashville, they produced a governing document called the Prescript. The Prescript described the Klan as a political organization opposed to black enfranchisement and in favor of southern autonomy and the strengthening of white political power. It also detailed a complex and rigidly hierarchical organization. At this time, Nathan Bedford Forrest was probably chosen as the Klan’s first Grand Wizard. Other prominent men like Albert Pike, Matthew Galloway, and John B. Gordon joined around this time and used their influence to spread the organization.

The tightly organized, politically focused regional Klan envisioned by the Prescript never materialized. Each state faced substantially different political situations, making coordination difficult; Klan groups had few effective ways to organize or communicate; and the federal government soon became aware of the Klan and worked to suppress it. The Tennessee leaders disbanded the group in 1869. Klan activity persisted, and even increased, after this disbandment, but the disbandment spelled the end of the attempt to centralize the Klan.

The Klan, instead, became an amorphous movement that included a range of clandestine groups in many parts of the South that exploited postwar political, social, and economic disorganization for various ends. Each group had its own composition, goals, and tactics. Some had political goals, such as intimidating Republican voters, politicians, and local government officials. Others hoped to prevent the establishment of schools for freedpeople. Some styled themselves after western lynch mobs and portrayed themselves as protecting the weak and punishing crime and immorality. Some were conventional criminal gangs using a Klan identity to escape detection or punishment for theft, illegal distilling, rape, or other violent and sadistic acts. Others apparently had economic goals, such as driving away freedpeople competing with them as laborers or tenants, terrifying workers into compliance, or forcing tenants to abandon their crops, animals, or improvements. Still others engaged in Klan violence to settle personal disputes involving land use, social status, feuds, or sexual competition.

Perpetrators of Klan violence varied from place to place. Some Klan groups consisted largely of privileged, though temporarily dispossessed, southern elites, who rode horses and wore extravagant costumes. Other, probably most, Klan groups consisted of poor whites. Many Klan groups, for instance, too poor to own horses, committed their attacks while riding mules or going on foot and either did not disguise themselves or simply covered their faces with cheap materials like painted burlap sacks or squirrel skins.

Klan tactics differed as much as did membership and apparent motives. Some Klan groups were largely performative, parading through the streets and leaving cryptic messages about town. Most, however, brought intimidation and/or violence against specific targets. Even when they were pursuing goals that were not primarily political, their victims were almost always Republicans and were usually freedpeople. By targeting these groups, Klansmen frequently gained broad support among local Democratic whites. The most common form that intimidation and violence took was the nighttime visit, in which a group of Klansmen would descend upon the home of their victim and either force their way in or demand that their victim come outside. Klan visits frequently involved property theft from victims, whether the Klansmen were “confiscating” firearms or simply stealing money, food, or household goods. Some Klansmen threatened their targets, requiring that they renounce a political party, leave town, or otherwise change their behavior. Other Klan groups whipped their victims. A number of Klan attacks were sexual in nature: Klansmen raped victims, whipped them while naked, forced them to perform humiliating sexual acts, or castrated them.

Klansmen sometimes killed their victims. Because of the weak and disorganized nature of local government at the time and because of the difficulty in defining which attacks should count as Klan attacks, it is impossible to get reliable numbers on how many people the Klan killed, but the number is at least several hundred. In most cases, Klansmen killed victims execution style, by either shooting or hanging them. Klansmen shot others while they were attempting to escape. Klan groups killed some victims, particularly those who were politically connected, through ambush. Additionally, Klan groups committed some larger collective murders, such as the abduction and killing of ten freedmen in Union County, S.C., in spring 1871.

Freedpeople and white Republicans often attempted, sometimes with success, to prevent or resist Klan threats and violence. Those anticipating attack fled to nearby cities for safety or “laid out,” spending the night out of doors in their fields. Others gathered friends and family, or, in South Carolina, black militiamen, to stand guard for them. At the same time, Republican leaders and local agents of the federal government gathered information about Klan activity and plans and sent it urgently to state and federal officials, in the hope of gaining protection. Klan survivors and witnesses often agreed to testify to state or federal committees, even at grave personal risk. In the face of threatened violence at election time, Republicans tried various strategies, such as approaching the polls in groups. Faced with an attack, some who had managed to arm themselves met approaching Klansmen with gunfire. Unarmed victims sometimes used household implements as weapons. Others attempted to reason or plea with their captors; frequently, they recognized some of their attackers and directly called upon their protection.

The federal government, convinced that local and state efforts were ineffective, took several steps to suppress the Klan but could intervene only when Klan violence had a political nature. Congress passed a series of bills popularly referred to as the Enforcement Acts, intended to enforce the voting rights granted to freedmen under the Fifteenth Amendment. The first, passed on 31 May 1870, then strengthened and supplemented by another act passed on 28 February 1871, made it a federal crime for individuals to conspire or wear disguise to deprive citizens of their constitutional rights and set up federal mechanisms for the arrest, prosecution, and trials of accused offenders. The most controversial, popularly called the Ku Klux Force Act, which was passed on 20 April 1871, gave the president the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and to send federal troops to areas incapable of controlling Klan violence, even without the invitation of a governor. It also made punishable by federal law several common forms of political Klan behavior and forbade Klansmen from serving on juries. President Ulysses S. Grant took limited advantage of this legislation, sending small numbers of troops to some of the hardest-hit areas. South Carolina became the focus of federal Klan enforcement: Grant suspended habeas corpus briefly in nine counties, federal marshals and troops made hundreds of arrests, and the federal district court began a high-profile series of trials of accused Klan leaders in fall 1871.

The Ku Klux Klan was significant in federal politics, particularly during the Johnson impeachment and in the federal elections of 1868 and 1872. The Klan first emerged to national notice during the impeachment trials, as Johnson’s opponents attempted to associate him with the Klan. In the election of 1868, supporters of Ulysses S. Grant, the Republican candidate, labeled supporters of Democrat Horatio Seymour as the “Ku-Klux Democracy.” Though the election of 1872 occurred after the Klan’s decline, the Klan was even more central to it than to the election of 1868. Grant’s supporters attempted to tie Horace Greeley, the Liberal Republican and Democratic candidate, to the Klan, claiming that a vote for Greeley was a vote for Klan resurgence. Greeley’s supporters claimed that Grant was using the Klan as a “bugbear” and that Klan suppression was a pretext for unconstitutionally increasing the reach of federal power.

In the months after winning reelection, Grant stopped federal Klan arrests and trials and quietly released those dozens of men who had been committed to federal prison as Klansmen. Besides some interest surrounding the publication of Albion Tourgée’s 1879 Klan-themed novel, A Fool’s Errand, the Ku Klux Klan would not be significant in American social and political life, or even in cultural representation, until its 20th-century revival.

ELAINE FRANTZ PARSONS

Duquesne University

Steven Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (2003); Kwando Kinshasa, Black Resistance to the Ku Klux Klan in the Wake of the Civil War(2006); Scott Reynolds Nelson, Iron Confederacies: Southern Railways, Klan Violence, and Reconstruction (1999); Mitchell Snay, Fenians, Freedmen, and Southern Whites (2007); Allen Trelease, White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (1971); Xi Wang, The Trial of Democracy: Black Suffrage and Northern Republicans, 1860–1910 (1997); Lou Faulkner Williams, The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials, 1871–1872 (1996).

Ku Klux Klan, Second (1915–1944)

The Ku Klux Klan was never more powerful than it was in the 1920s. At that time, it thrived as a nativist and racist organization, championing the rights and superiority of white Protestant Americans. Unlike the first Klan of the Reconstruction era, the second Klan was a nationwide movement. At its height, it boasted 5 million members in 4,000 local chapters across the country, although some historians contend that it never had more than 1.5 million active members at any one time. The Klan’s main appeal was its promise to restore what it deemed traditional values in the face of the transformations of modern society, and it was most popular in communities where it acted in support of moral reform. Klansmen opposed the social and political advancement of blacks, Jews, and Catholics, but they also virulently attacked bootleggers, drinkers, gamblers, adulterers, fornicators, and others who they believed had flouted Protestant moral codes.

Although the Klan was strongest in the Midwest, in states like Indiana and Illinois, where it peddled its slogan of “100% Americanism” to great effect, it was still in many ways a distinctly southern organization. William Simmons, a former Methodist preacher from Alabama, reestablished the Klan in an elaborate ceremony atop Stone Mountain, just outside of Atlanta, Ga., on Thanksgiving Day in 1915. Even as the organization spread across the country, its leadership and base of operations remained in Atlanta. Moreover, Klansmen regularly engaged in rituals and rhetoric that drew upon southern traditions from the Reconstruction Klan and Lost Cause mythology to enact their nationalistic agenda.

Klans throughout the country held public rallies, staged parades, and engaged in various political activities, mostly attempting to influence political leaders to adopt Klan positions. Klansmen tended to be solid, churchgoing middle- and working-class men who were concerned about the loss of traditional white, patriarchal power in the face of urbanization, immigration, black migration, feminism, and the cracking of Victorian morality. As much as they expressed contempt toward those at the bottom of the social ladder, they railed against the excesses of Wall Street and Hollywood, leading one historian to characterize their politics as a kind of “reactionary populism.”

In wanting to present itself as a mainstream movement that stood for law and order, the Klan, as an organization, prohibited and disavowed acts of violence. That did not stop individual Klansmen, in full Klan regalia, from committing numerous acts of terror and violence, especially in southern states. Klansmen whipped and tortured blacks who transgressed Jim Crow racial codes, but they also targeted whites who had violated moral codes. They engaged in threats, beatings, and tarring and featherings to humiliate their victims. During the 1920s, probably over 1,000 violent assaults took place in Texas and Oklahoma alone, and over 100 assaults each in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. In 1921, the New York World published a three-week serial exposé on the Klan, highlighting its moneymaking scams, its radical propaganda, and its violence. The articles led to a congressional hearing on the organization, which ended abruptly with no conclusion.

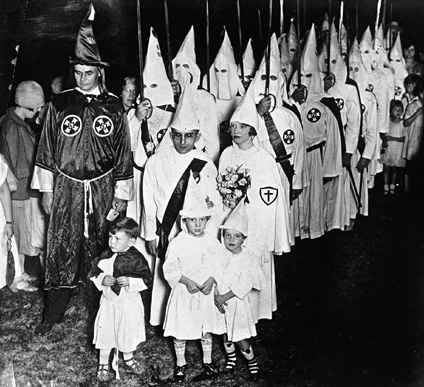

Ku Klux Klan members with children, ca. 1912–30 (Library of Congress [LC-DIG-npcc-27617], Washington, D.C.)

Although the Klan supported traditional gender roles, white women received their own recognition in the formation of the Women’s Ku Klux Klan in 1915. Implemented as a separate organization, the Women’s Ku Klux Klan bound itself to the Klan’s ideals but remained independent of the men’s organization. As Klanswomen, members marched in parades, organized community events, and recruited new Klan members—primarily children. As it grew in numbers and visibility, the Klan expanded to include its youth. In 1923, the Klan voted to create two auxiliaries, the Junior Ku Klux Klan for adolescent boys and the Tri-K-Klub for teenage girls. The Junior Klan sought to promote the principles of the Ku Klux Klan in preparation for adult male membership. The Tri-K-Klub, under the umbrella of the Women’s Ku Klux Klan, taught girls the ideals the Klan desired in wives and mothers, such as racial purity, cheerfulness, and determination.

In the late 1920s, the Klan’s power began to wane and its membership declined. After the 1921 hearings, mainstream newspapers and the black press increased their reportage of Klan violence, and the NAACP began its own documentation of Klan terror. In addition, a number of prominent Klan leaders were caught in embarrassing scandals, exposing the hypocrisy of the organization. Finally, the Klan’s insistence that its movement was democratic and patriotic began to appear contradictory. For some, the Klan in America began to resemble the rising fascism in Europe, a perception only furthered by the increasing radicalism of Klan leaders. By 1930, the national Klan movement had gradually retreated into the South, where the economic crises of the Great Depression further weakened the organization. In that year, it claimed barely 50,000 members. In 1944, the Internal Revenue Service presented the Second Ku Klux Klan with a bill for $685,000 in unpaid taxes. Unable to pay, the Imperial Wizard on 23 April 1944 revoked the charters and disbanded all Klaverns of the Klan.

KRIS DUROCHER

Morehead State University

AMY LOUISE WOOD

Illinois State University

Charles C. Alexander, The Ku Klux Klan in the Southwest (1965); Kathleen M. Blee, Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s (1991); David Chalmers, Backfire: How the Ku Klux Klan Helped the Civil Rights Movement (2003); Kenneth T. Jackson, The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930 (1967); Nancy K. MacLean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan (1995); Wyn Craig Wade, The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America (1997).

Mardi Gras Indians

The Black Mardi Gras Indians are African Americans (some of whom claim American Indian ancestry) who perform a colorful, elaborate, and symbol-laden ritual drama on the streets of New Orleans. Their dynamic street performances feature characters that play specific roles, polyrhythmic percussion and creolized music texts, and artistic suit assemblages that reflect ritual influences from both Indian America and West Africa. With roots stretching back to the 18th century, this unique tradition has given rise to a rich array of customs and artistic forms and continues to testify to the historical affinity of the region’s Indians and African Americans.

New Orleans hosts two Mardi Gras every year. One is the highly commercialized celebration planned for the aristocratic krews, with their carnival balls and float parades. The other is the walking and masking festival that includes Baby Dolls, Skeleton Men, and the Mardi Gras Indians. Each celebration features unique traditions that are deeply rooted in a distinctive culture and environment.

The Black Mardi Gras Indians draw upon American Indian, West African, and Caribbean motifs and theatrics to create a unique creolized folk ritual. In Louisiana, these three cultural groups came together during the French and Spanish colonial periods. Indians were African Americans’ first allies in resisting European enslavement and general labor oppression; and they too were often enslaved. The shared experience of bondage led to many intermarriages between West Africans and Indians, yielding a legacy of mixed ancestry that is still evident among many Mardi Gras Indians hundreds of years later. Such ancestry, however, has never been a criteria for joining the Indian “tribes” or “gangs.” Wearing and performing the Indian mask has instead long served as a means of escape and a way to resist and protest the white hegemony that has so long defined Jim Crow New Orleans.

No one knows exactly when the Mardi Gras Indian tradition started, but it was first documented in the late 1700s. Its early years were marked by fierce rivalries between African American “tribes” from New Orleans’s Uptown and Downtown districts, with the masked marchers carrying weapons and attacking their “tribal” adversaries. In recent decades, the resolution of these territorial rivalries has shifted from a physical to an aesthetic plane.

In today’s New Orleans, neighborhood tribes—dressed in elaborately beaded and feather-laden costumes—display their dazzling artistry every year on Mardi Gras Day, St. Joseph’s Day (March 19), and Super Sunday (the third Sunday in March). The colorfully costumed Indians parade from house to house and bar to bar, singing call-and-response songs and boasting chants to the exuberant accompaniment of drums, tambourines, and ad hoc instruments. Alongside of and behind the procession, “second liners”—relatives, friends, and neighborhood supporters—strut, dance, and sing along. When the group meets an opposing tribe, the street is filled with dancing and general “showing off,” as the costumed participants proudly display their masques, hand signals, and tribal gestures, exhibiting a shared pride in “suiting up as Indian.” This street theater—with its percussive rhythms, creolized song texts, boasting chants, and colorful feather and bead explosions—reflects Indianness through an African-based lens of celebration and ritual.

The most obviously “Indian” element of these performances is the full-body masque worn by tribe members, replete with a feather crown and detailed beadwork that typically depicts Native American themes. Though clearly a tribute to Native American culture, these elaborate costumes also show an overt connection to West African assemblage styles and beading techniques. Most of the patchwork scenes depicting Native Americans are flat and show warriors in battle or other stereotypically “Indian” scenes. Among Downtown tribes, however, the beaded images are more varied and often break into sculptural relief. Rather than conveying Native American themes, they offer Japanese pagodas, aquatic scenes, Egyptian regalia, and whatever other images their creators can imagine and then craft. Constructed anew each year, each suit testifies to countless painstaking hours on the part of the Indian who wears it in Mardi Gras.

The Wild Tchoupitoulas in Les Blank’s film Always for Pleasure, 1978 (Michael P. Smith, photographer, Brazos Films/Arhoolie Records, Los Cerrito, Calif.)

The Mardi Gras Indians’ lavish outfits and spirited performances also reveal a distinct social hierarchy within each tribe, with different positions—chief, spy boy, flag boy, and wild man, in descending order of status—presenting themselves differently and filling particular roles in the unfolding performance. Many tribes now also crown their own queens, reprising and reinvigorating a role that was less prominent in the early, more violent years.

The unique tradition of the Mardi Gras Indians has given rise to an array of distinctive artistic forms and shared customs. At the same time, this tradition displays strong ancestral ties to West Africa and testifies to the historical affinity of Indians and Africans, two groups that played leading roles in the creolization of New Orleans. In essence, the Mardi Gras Indians’ ritual performances speak to the need to celebrate life and death in all of their splendor and to address power and enact resistance through masking and dramatic street theater.

JOYCE MARIE JACKSON

Louisiana State University

Joyce Marie Jackson and Fehintola Mosadomi, in Orisha: Yoruba Gods and Spiritual Identity, ed. Toyin Falola (2005); Maurice M. Martinez and James E. Hinton, The Black Indians of New Orleans (film, 1976); Michael P. Smith, Mardi Gras Indians (1994).

Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Celebrated on the third Monday in January, the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday honors the civil rights leader and has special meaning in the South where he was born and where his triumphs and the tragedy of his assassination took place. Michigan congressman John Conyers introduced the legislation to support the holiday shortly after King’s death, but Congress did not pass it until over a decade later, after a national promotional campaign led by Atlanta’s King Center, which overcame opposition led by North Carolina senators John East and Jesse Helms. President Ronald Reagan signed the King Holiday law in 1983. President Bill Clinton signed the King Holiday and Service Act in 1994, which honored King’s legacy by encouraging public service work on his holiday. Some southern states did not officially recognize the holiday as a paid one for state employees at first, and some combined it with commemoration of Confederate heroes, especially Robert E. Lee, whose 19 January birthday was near King’s actual birthday of 15 January. Some southern whites still use the holiday ironically to honor Civil War heroes, but in 2000 South Carolina became the last southern state to officially recognize the King Holiday as a paid state holiday for employees, giving it official legitimacy.

The King Holiday has had spiritual, political, and commercial significance. Martin Dennison notes that “this holiday reverentially recalls ‘St. Martin Luther King.’” King led a social movement, with profound political impact in the South, but he was a religious figure as well. While leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the mid-1950s, he became known as Alabama’s Modern Moses, and his assassination in April 1968, shortly after Palm Sunday, evoked the religious language of martyrdom. King Holiday commemorations often occur in black churches, with homilies, prayers, and religious music making the day one on the South’s sacred calendar.

The holiday has also had political meanings. On 17 January 1998, in the 30th year after King’s death, 50 Indiana Klansmen staged a rally in Memphis, the site of King’s assassination. A crowd of 12,000 black and white civil rights supporters gathered in response, with a few young gang members resorting to violence, tarnishing King’s nonviolent legacy. More important, peaceful rallies occurred throughout the city, affirming King’s contributions. In January 2000, the King Holiday became the focus for advocates of the Confederate battle flag atop the South Carolina state capitol, but counter demonstrators rallied to remove the flag, which state legislators authorized later that year.

The King Holiday is widely honored now, partly as a day of rest and commercialization. King Holiday sales market much American produce far removed from civil rights, but this represents a normalization of the day in typical American fashion and its wide acceptance. Critics suggest its commercialization trivializes the holiday’s meaning. The day continues, though, to include projects celebrating social justice, racial reconciliation, tolerance, nonviolence, and the special place of African Americans in the nation’s democratic heritage. Southern churches, community centers, arts centers, public schools, town halls, and other public facilities host these activities, recognizing the centrality of African Americans to the region’s historical memory. On 19 January 2009, the King Holiday included more than 13,000 service projects.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Martin Dennison, Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar (2002).

Mason-Dixon Line

“An artificial line . . . and yet more unalterable than if nature had made it for it limits the sovereignty of four states, each of whom is tenacious of its particular systems of law as of its soil. It is the boundary of empire.”

Writing his history of the Mason-Dixon Line in 1857, James Veech reflected the well-founded anxieties of the day—the fear that the horizontal fault between slave and free territory was about to become an open breach. Although the Mason-Dixon Line was long associated with the division between free and slave states, slavery existed on both its sides when it was first drawn. To settle a long-standing boundary dispute arising from ambiguous colonial charters, the Calvert and Penn families chose English astronomers Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to survey the territory. After four years of work (1763–67), they fixed the common boundary of Maryland and Pennsylvania at 39°43’17.6” north latitude, marking their line at every fifth mile with stones bearing the arms of the Penn family on one side and the Calvert crest on the other. Halted in their westward survey by the presence of hostile Indians, their work was concluded in 1784 by a new team, which included David Rittenhouse, Andrew Ellicott, and Benjamin Banneker.

In 1820, the Missouri Compromise temporarily readjusted the fragile tacit balance between slave and free territory and extended the Mason-Dixon Line to include the 36th parallel. By that date, all states north of the line had abolished slavery, and the acceptance of the line as the symbolic division both politically and socially between North and South was firmly established.

The Mason-Dixon Line has been a source of many idiomatic expressions and popular images. Slogans (“Hang your wash to dry on the Mason-Dixon Line”) originated with early antislavery agitation; variations on the theme (Smith and Wesson line) and novel applications (the logo for a cross-country trucking firm) are contemporary phenomena. A popular shorthand for a sometimes mythic, sometimes very real regional distinction, the term “Mason-Dixon Line” continues to be used, and its meaning is immediately comprehended.

ELIZABETH M. MAKOWSKI

University of Mississippi

Journals of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon (1969); John H. B. Latrobe, History of Mason and Dixon’s Line (1855); James Veech, ed., Mason and Dixon’s Line: A History (1857).

Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike

The subject of two award-winning documentary films—At the River I Stand and I Am a Man: From Memphis, a Lesson in Life—at least one play, and several books, the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike has become emblematic of the universal struggle for dignity and respect by downtrodden people. Its iconic slogan—“I AM a Man!”—has been appropriated by labor struggles in the United States and internationally. And its memory is renewed every year on 4 April—the eve of a planned march in support of the sanitation workers and the date of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

In February 1968, nearly 1,300 sanitation workers walked off their jobs in a strike for collective bargaining rights that would ultimately represent a pivotal moment in which the labor movement, the antipoverty movement, and the black freedom movement coalesced. The quest for union recognition could hardly have been more dramatic. African American workers with wages so low that their families qualified for food stamps, with neither sick pay nor disability insurance, whose families lived in the very poorest neighborhoods in the city, confronted a segregationist mayor and city administration determined to deny them union recognition. The garbage men had been attempting to win union recognition since 1960, but their dramatic walkout on 12 February was precipitated by the deaths of two coworkers who were crushed inside a garbage truck while waiting out a rainstorm (an electrical malfunction tripped the mashing mechanism). The striking sanitation workers, who had joined Local 1733 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, risked instant dismissal; federal law did not accord municipal employees the protections it extended to private-sector workers.

What began as a strike transformed into a mass community movement two weeks later after city police officers sprayed the workers and their supporters, including African American ministers, with mace. Even the most well-heeled among them determined that the struggle for dignity and respect was not only for the poorest and most maligned but for all African Americans. Although the gendered slogan may seem relevant only to men, women—especially the factory workers and welfare rights activists who became the backbone of the support movement—saw in it a struggle against not only the racist indignities suffered by the men but also those confronted by black women.

When King arrived on 18 March to address a mass meeting, he was stunned at the turnout of 15,000. “Now, you are doing something else here!” he declared. “You are highlighting the economic issue. You are going beyond purely civil rights to the question of human rights.” For King, the struggle for human rights was about power: “Let it be known everywhere that along with wages and all of the other securities that you are struggling for, you’re also struggling for the right to organize and be recognized. This is the way to gain power—power is the ability to achieve purpose. Power is the ability to effect change.”

That struggle for power, born out of a quest for justice among black workers earning starvation wages and facing racist indignities on a daily basis, continues to have meaning today.

LAURIE B. GREEN

University of Texas at Austin

Laurie B. Green, Battling the Plantation Mentality: Memphis and the Black Freedom Struggle (2007); Martin Luther King Jr., in All Labor Has Dignity, ed. Michael K. Honey (2011).

Migrant Workers

Migrant workers for agriculture, forestry, and fisheries emerged as distinct social classes during the period following the Civil War, when migrant crews seasonally supplemented the work of sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and debt peons. During the first decades of the 20th century, the demand for migrant workers grew with the increase in fruit and vegetable production along the Eastern Seaboard to supply urban markets, resulting in the development of southern- and Caribbean-based crews of African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Puerto Ricans. African Americans and Puerto Ricans, based primarily in Florida and Puerto Rico, supplied labor to farms, forests, and seafood plants as far north as Maine, while Mexican Americans, based in south Texas, supplied labor across the Midwest and Great Plains. World War II drew many of these migrant workers out of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries and into the defense industry, stimulating the U.S. federal government to develop a class of migrant workers that could supply wartime food needs. By constructing labor camps and creating guest-worker programs to access foreign labor, federal officials assisted with recruiting and transporting migrant labor. Following the war, the U.S. government relinquished control of the migrant labor supply to grower associations and labor contractors.

Southern migrant labor began shifting from primarily domestic to primarily international supply regions during the 1960s and 1970s, creating an underclass of largely undocumented migrant workers from Mexico and Central America, which continues today. Within the migrant labor force, upward mobility is limited to workers who can become labor contractors or supervisors, and the majority remain confined to class positions that provide relatively low annual incomes—30 percent of all farmworkers have family incomes below federally established poverty levels. When undocumented, paid by the piece rather than hourly, and working for labor contractors rather than directly for companies, migrant labor’s relationship to capital has been stripped of worker protections in the form of guaranteed minimum wages, unemployment insurance, and health and safety standards. These conditions lead to high annual labor turnover rates, with 16 percent of all those surveyed in the National Agricultural Worker Survey reporting that they plan to work in agriculture for fewer than two or three years. High labor turnover has also led many southern employers of seasonal workers to embrace guest-worker programs. From 1943 to 1992, Florida sugar producers brought over 8,000 workers from the Caribbean annually, and today mid-Atlantic tobacco growers, forestry companies, and seafood processors utilize several thousand guest workers from Mexico under temporary contracts.

Mexican carrot worker, Edinburg (vicinity), Tex., 1939 (Russell Lee, photographer, USDA Historic Photos Collection [LC-USF33-011974-M3 (P&P)], Washington, D.C.)

In response to conditions of economic hardship facing migrant workers, several federal programs and networks of advocacy organizations have developed to provide migrant workers with legal services, food and medical assistance, education, job training, and other services. For many years, these organizations acted on behalf of migrant workers in lieu of collective bargaining. In North Carolina, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee, after a prolonged boycott of Mt. Olive Pickles, signed a union agreement with the North Carolina Growers’ Association, while the Coalition of Immokalee Workers forced a piece-rate increase in Florida’s tomato fields by organizing farmworkers and boycotting Taco Bell and other large buyers of Florida tomatoes. Similar collective bargaining successes have not been achieved by migrant forestry or seafood workers, most of whom are temporary foreign guest workers carrying H-2B visas.