DESIGNED FOR PLEASURE

Cities designed for pleasure offer a more light-hearted way of life, new social interactions, a recharging of the batteries; they offer a change from the same old, same old … a place to start over, to discover yourself …

‘Whatever your flavour, you’ll find it in Brighton’, says the Lonely Planet guide. In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen observes: ‘They arrived in Bath. Catherine was all eager delight; her eyes were here, there, everywhere. She was come to be happy, and she felt happy already.’

Bath and Brighton are our very own Las Vegases; both exploding in population from tiny bases, Bath growing twelvefold in the eighteenth century and Brighton seventeenfold in the nineteenth, faster than any other English cities. Their growth was fuelled by Georgian building booms, as intense in their way as the expansion of Las Vegas since the 1960s.

SO, WHAT SHOULD YOU LOOK OUT FOR IN A CITY DESIGNED FOR PLEASURE?

1. A ‘creation myth’ – in both cases, spa waters with special properties.

2. A ‘master of ceremonies’ to create social cachet for the place – Beau Nash in Bath, the Prince Regent in Brighton.

3. Promenades designed for social interaction – the Esplanade in Brighton, the paths, squares and parks of Bath.

4. Pleasure gardens – Sydney Gardens in Bath, St Ann’s Well Gardens in Brighton; and, of course, the piers.

5. Many places of entertainment – theatres, vaudeville, racecourses, festivals.

6. Gorgeous Georgian areas, driven by the ‘building aristocracy’ – the Woods in Bath, the Wilds in Brighton.

7. Railway stations that arrive in great curving sweeps. After all, visitors have always been the raison d’être of the pleasure cities.

SO MUCH PERFECTION IN A ‘HOLLOW OF THE HILLS’

Bath

Bath is unlike any other British city, all planned perfection around a single glorious era of leisure and intrigue, with none of the ‘edginess’ usually associated with the urban scene.

Bath has a striking setting in a ‘hollow of the hills’, with the River Avon running through its heart. From many vantage points on the surrounding hills you get excellent panoramas across the city; and from many points within the city you can look straight out along a street and up into the countryside; always a great joy in a smaller city, a glimpse of the country beyond the urban landscape. Almost all the open land on slopes around the city is specially protected to retain the mixture of woodland and meadows, and this contributes greatly to Bath’s immense charm. And the city is small-scale: you can walk out of the city from Bath Abbey to Bathwick Meadows in little more than fifteen minutes.

The city’s fame was assured by a unique natural asset – very hot water bubbling up from the ground as geothermal springs. The Romans built baths and a temple here. In the seventeenth century, claims were made for the curative properties of water from these springs, and Bath became famous as a spa town in the Georgian era.

Unlike so many British cities, Bath is emphatically not a Victorian-inspired or Victorian-looking city. Whilst Bath only doubled in size during the nineteenth century, neighbouring Bristol grew fivefold and became the dominant economic force in the region, whilst Bath’s fashionability faded.

In 1987, the recognition of Bath’s glorious architectural heritage was confirmed when UNESCO awarded the whole city World Heritage status – one of only two cities in the world to be designated in its entirety, the other being Venice.

Today, tourism and professional services underpin the city’s employment. More than one million visitors stay and there are four million visits each year. It has become a fashionable ‘lifestyle haven’ for publishers, software programmers, lawyers and accountants.

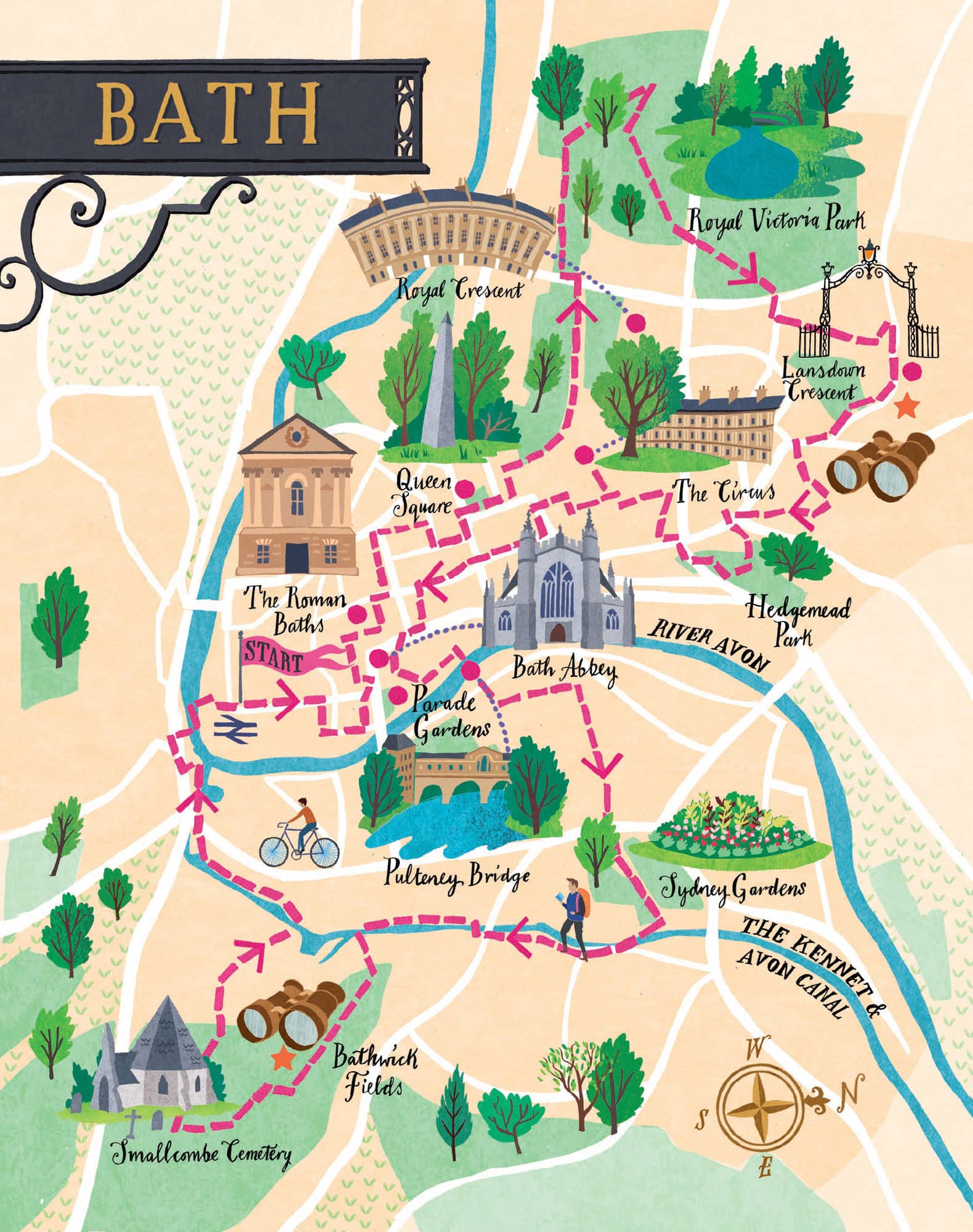

THE WALK

We alight at the delightful Bath Spa station (1840), designed by Brunel; but setting out on our walk we find ourselves having to skirt around the rather unedifying neo-Georgian shopping centre before reaching the undiluted Georgian joy of the city.

The Bath of our imagination soon becomes a reality as we reach South Parade, Duke Street, North Parade and Pierrepont Street. Almost all the houses on these streets, dating back to the 1740s, are Grade I listed.

The Roman Baths date back to AD 60 when the Romans constructed a temple to Sulis on the site, and the bathing complex was gradually built up over the next 300 years. The Baths themselves are now below the current street level and the spring is housed in eighteenth-century buildings. Bath Abbey was a former Benedictine monastery, founded in the seventh century, reconstructed in the twelfth century and subject to major restoration by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the 1860s. The abbey is one of the best examples of Perpendicular Gothic architecture in the region, with a particularly fine vault ceiling.

The Grand Pump Room, built by Thomas Baldwin, was the centre of Bath’s social scene at the start of the nineteenth century. In Jane Austen’s words, ‘Every creature in Bath was to be seen in the room at different periods of the fashionable hours.’ On arrival in the city, you were expected to write your name, address and the length of your stay in ‘the Register’. Everything ‘Society’ needed to know about you could be gleaned from these inputs, an early version of Facebook.

Queen Square is the first element in ‘the most important architectural sequence in Bath’, which includes the Circus and the Royal Crescent. It was the first speculative development by the architect John Wood the Elder, who later lived in a house on the south side of the square, apparently with the best view (builders always seem to wangle the best houses).

He understood that polite society enjoyed parading, and in order to do that he provided wide streets, with raised pavements, and a thoughtfully designed central garden in Queen Square. From the square, we take the Gravel Walk; this is the secluded, gently rising walk that Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot take in Persuasion when they are finally reconciled. And it’s not too fanciful to say it has a peace and auspiciousness about it that promotes calm and harmony.

The Royal Crescent (1774) takes our breath away, the acme of architectural beauty, with its ha-ha wall emphasising its ‘rus in urbe’ ambitions. It has the ‘definitive’ Georgian crescent feel about it and does it better than anywhere else. But all is not what it seems; whilst Wood designed the great curved façade of what appear to be about thirty houses, with Ionic columns on a rusticated ground floor, that was the extent of his input. Each purchaser then bought a certain length of the façade, and employed their own architect to build a house to their own specifications behind it. A perfect way to combine overall uniformity with individual flexibility.

‘Bath is the worst of all places for getting any work done.’ WILLIAM WILBERFORCE

Royal Victoria Park (23 hectares, 57 acres) is a beautiful expanse of green parkland. Originally an arboretum, the park dates back to 1829 and is named after Queen Victoria, who officially opened it in 1830 at the age of eleven. During her visit, it is said that a local resident commented on the thickness of her ankles. The observation was duly reported to the princess, causing her to shun the city for the duration of her reign. The only time she passed through again was by train from Bristol to London, when she reportedly kept the blinds in her carriage firmly drawn. Bath didn’t quite give up on Victoria, though. The three-sided Obelisk of the Victoria Majority Monument was erected in 1837 to honour the princess’s eighteenth birthday.

The Botanical Gardens were formed in the north-west area of the park in 1887. They contain a fine collection of plants that thrive on limestone, the same strata that are so amenable to the hot springs.

Jane Austen may have taken this very same sneaky route that we take up Park Street to avoid the throngs, as she loved walking to relax and have time on her own (notably to Lansdown, the route we are taking). She writes about her Bath walks often in her letters: ‘The pleasure of walking and breathing fresh air is enough for me, and in fine weather, I am out more than half my time.’

We are so pleased with our little ‘snicket’ up the hill as it comes out in front of the stupendous Lansdown Crescent, laid out in the late 1780s by John Palmer. The sheep spending part of the year in the field beneath the crescent belong to farmer Douglas Creed from Kelston. He began using the field in the early 1990s, so is very familiar with the practicalities of the site. He prefers to mate his sheep relatively late so that lambs are born after the worst of the winter is over. He also needs to wait until the lambs are of sufficient size not to be able to squeeze through the railings into Lansdown Crescent and face danger from passing traffic.

Cutting across east we reach the steep Hedgemead Park (2 hectares, 5 acres). Unusually for a park, it came about by an accident rather than years of community petitioning, when in 1889 the houses below Camden Crescent collapsed due to a landslide. The layout of the paths and terrain were engineered to prevent the possibility of future landslides.

The Circus (1768) consists of three long, curved terraces designed to form a circular space intended for civic functions and games. The inspiration was the Colosseum in Rome and, like the Colosseum, the three façades have a different order of architecture on each floor: Doric on the ground level, Ionic on the middle floor, and finishing with Corinthian on the upper floor, the style of the building thus becoming progressively more ornate as it rises.

The Assembly Rooms (1769) formed the hub of fashionable Georgian society in the city, the venue being described as ‘the most noble and elegant of any in the kingdom’. People would gather in the rooms in the evening for balls and other public functions, or simply to play cards. Mothers and chaperones bringing their daughters to Bath for the social season, hoping to marry them off to a suitable husband, would take their charge to such events where one might meet all the eligible men currently in the city.

The obelisk in Queen Square was erected by Beau Nash in honour of Frederick, Prince of Wales

Royal Victoria Park has many secluded spots to relax in

The Royal Crescent encircles a beautiful open green space

Pulteney Bridge in its full majesty

The Corridor (1825) is one of the oldest shopping malls in the country. Customers were originally serenaded in galleries overhead, which are still there, a step up from piped muzak! It has perhaps seen better days shopping-wise but makes an interesting cut-through, coming out in front of the Guildhall, built in the 1770s by Thomas Baldwin.

Parade Gardens (1 hectare, 2.5 acres) is worth visiting for the views across the river and especially the view upstream to Pulteney Bridge. The bandstand is in that rarely found Bath architectural style, the not-Georgian. It dates back to 1925, replacing an earlier nineteenth-century version. The large building overlooking the Parade Gardens from Grand Parade is The Empire, built in 1898 as a hotel. The interesting rooftop, depicting cottages, a townhouse, a manor house with Dutch-style gable and a castle is said to have represented the different classes of Victorian customer who were all welcome to use the hotel!

Pulteney Bridge (1774) is one of the defining landmarks of Bath, built to connect the city to the new Georgian town of Bathwick. Designed by Robert Adam in Palladian style, it is exceptional in having shops built across its full span on both sides. Laura Place is named after Henrietta Laura Pulteney, whose father owned the Bathwick Estate, which comprises four streets joined on the diagonals of Laura Place. Pevsner describes it as ‘one of the most impressive of all Neoclassical urban set pieces in Britain’.

Then we head left and up through Henrietta Park (2.8 hectares, 7 acres), laid out to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria of 1897 (it seems they didn’t give up on her). We relax for a while in the Garden of Remembrance, a particularly tranquil spot.

Sydney Gardens (4 hectares, 9.9 acres) was created in the 1790s as a commercial pleasure grounds, in the tradition of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. The Sydney Hotel, now the Holburne Museum, was built in 1796 as a casino and gateway to the gardens. It was entered through archways that took you first into a foyer and then through gauze curtains decorated with Apollo strumming his lyre, into a landscape of pure pleasure. Musicians played on the terrace above so that the visitor entered a magical scene of supper boxes, entertainments, masques, follies and numerous places of assignation. The gardens themselves included a labyrinth, grotto, sham castle and an artificial rural scene with moving figures powered by a clockwork mechanism. As Jane Austen remarked: ‘It would be very pleasant to be near Sidney Gardens! – we might go into the Labyrinth every day.’

The Kennet and Avon Canal passes through the gardens via two short tunnels and under two cast-iron footbridges dating from 1800. There is also an iron footbridge over the railway which was designed by Brunel and built in 1840. Cleveland House is one of the treasures of the canal. Built by the Duke of Cleveland as the headquarters for the canal company, it was built half on land and half over the canal, and had a magnificent two-storey boardroom over the canal, with a trap-door in the tunnel roof that was used to pass paperwork between clerks above and bargees below.

Canals provide a nature corridor through cities. David Goode, in Nature in Towns and Cities, writes about this particular stretch: ‘The lock gates are colonised by a tangle of water-loving plants including gypsywort, skullcap, pendulous sedge and wild angelica, with a profusion of liverworts covering the woodwork at the lower levels. One heron, oblivious to passers-by, has learnt to wait patiently by the lock gates where it catches small fish carried through the leaky gates.’

The Roman Baths date back to AD 60 when there was a temple to Sulis on the site

The Kennet and Avon Canal is not to be missed on a visit to Bath

The National Trust acquired Bathwick Fields (9.3 hectares, 23.7 acres) in 1984 with funds raised by the council and local people keen to see this meadowland preserved. From the top field, we marvel at a truly iconic view across Bath, from Beechen Cliff on our left to Lansdown Hill on our right, taking in views that have defined Bath since Georgian times.

The Smallcombe Cemetery (1.9 hectares, 4.7 acres), just south of Bathwick Fields, was opened in 1856. Population expansion had seen the Parish of Bathwick overwhelmed by demands for burials outside the city. At only £3, a ‘decent burial’ was affordable to most so artisans as well as aristocrats are buried here. Smallcombe remains the semi-wild, tranquil garden described when it opened as ‘secluded and even picturesque, a beautiful spot, commanding a fine view of the city’ and today is lovingly looked after by the Smallcombe Garden Cemetery Conservation Group.

For the final stretch, we return to the delights of the canal. Pumphouse Chimney was built in an ornate style as the wealthy residents on Bathwick Hill did not want to overlook an industrial-style chimney (how very Bath …). And then back over Halfpenny (Widcombe) Bridge. An earlier, wooden version of this footbridge had collapsed, tumbling dozens of people into the river. It was re-built in metal in the late 1870s and charged a halfpenny toll to recoup the building costs, hence its name. But don’t worry, you won’t need a halfpenny these days, and the structure looks robust. You will soon be delivered back safely to Bath Spa where our journey began.

LIBERATING, PROGRESSIVE, DESIGNED FOR PLEASURE

Brighton

This walk is a revelation – lots of green space, a bracing walk along the seafront, myriad intriguing lanes and buzzing city life.

The mainstay of Brighton’s economy for the first 700 years of its existence was fishing. Open land called the Hempshares, the site of the present Lanes, provided hemp for ropes; sails were made from flax grown in Hove; and boats were kept on the open land which became Old Steine. By the late sixteenth century Brighton’s eighty-boat fleet was the largest in southern England and employed 400 men.

But it was not until the early eighteenth century, with the population still only standing at 2,000, that the town began to grow in ambition. The contemporary fad for drinking and bathing in seawater as a cure for illnesses was encouraged by Dr Richard Russell who sent many patients to ‘take the cure’ in the sea at Brighton, published a popular treatise on the subject and moved to the town soon afterwards to cash in on the fashion.

From 1780, development of the Georgian terraces got underway, and the town was transformed from the ‘Cinderella’ of a fishing village (at that time called Brighthelmston) into the ‘fairy princess’ of a fashionable resort, with a name simplification to Brighton for good measure. The growth of the town was further spurred on by the patronage of the Prince Regent (later George IV) after his first visit in 1783. He spent much of his leisure time in the town and constructed the Royal Pavilion as a place for escape and indulgence.

Another spur to growth was the arrival of the London and Brighton Railway in 1841, which brought the town within reach of day-trippers from London. Today Brighton attracts over 8.5 million visitors annually and its tourism industry employs 20,000 people. But the city is also part of the digital economy – over 500 new media businesses have been founded in Brighton in the last decade.

N.B.: Brighton has about 400 restaurants, apparently more per head than anywhere else in the UK. This might well slow down your walk!

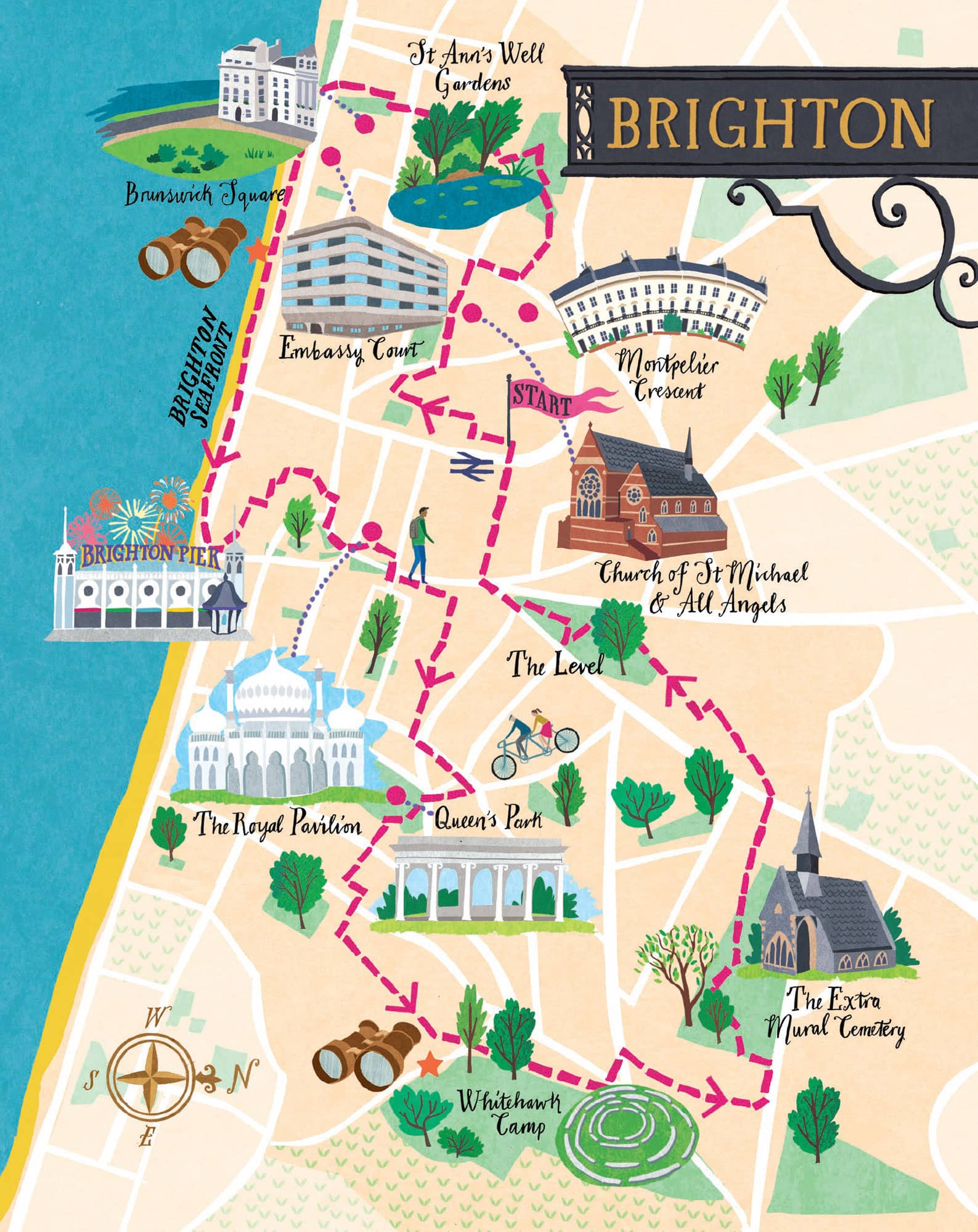

THE WALK

We emerge from our train into the beautiful engine shed of Brighton station (1841) in high spirits. The train to the coast from London has been a revelation, groups of friends spread across the seats chatting nineteen to the dozen, romantic couples of all ages and persuasions, parents with their young children, all with one thing in common – they are coming down to Brighton to have fun, as of course are we, tucked quietly into the corner of the carriage as all good urban ramblers should be.

Our route takes us up a steep slope and then along Camden Terrace, a narrow twitten (Sussex dialect for ‘passage’), emerging at St Nicholas’s Church (fourteenth century), a lovely little green spot. Situated on high ground, it is the oldest surviving building in Brighton, albeit much modified by Victorian improvers.

The first extension to the churchyard was built in 1824, across Church Street to the north. This has been converted into a playground. But the most significant change came in 1841 when land to the west of Dyke Road was acquired and used to form a much larger burial ground, containing a series of vaults. We take a quick detour through it. Then we head along Vine Place, our second twitten of the day, which gives access to the tiny one-storey cottages that were the original mill-workers’ cottages to Clifton Windmill. This windmill has gone but the miller’s house, Rose Cottage, is still here.

On our right, as we walk along Victoria Road, the Church of St Michael and All Angels (1862 and 1893) looms large, built to serve the affluent local community. According to its Grade I listing, ‘the architectural quality of both buildings and of their fittings, and the range and quality of the stained glass, make this a building of outstanding importance’. Most notably, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was closely involved with the decoration of the interior.

We positively drool as we peer down Montpelier Terrace at the beautiful 1840s stucco-clad terraced houses and villas, all beautifully maintained. The architectural partnership of Amon Wilds, his son Amon Henry Wilds and Charles Busby – the most important architects in Regency-era Brighton and Hove – were the driving force behind almost the entire Montpelier development, building nearly 4,000 new houses in the Regency style, quite some achievement.

The ultimate showpiece in these parts is Montpelier Crescent (1840s), envisaged to have a sight of the South Downs; but within ten years, the downland vista had been obscured by the construction of Vernon Terrace opposite. Never mind. There are still many things to enjoy about the crescent, not least the generous green space out in front.

Next, we come to the quaint St Ann’s Well Gardens (5.3 hectares, 13 acres), the spot where Brighton’s status as a health spa was born. It was Dr Richard Russell who first made St Ann’s Well famous by sending some of his clients to drink the water from a spring here. The Chalybeate (iron) spring became known as one of the finest natural springs in the whole of Europe. However, the distance of the spa from the centre of Brighton, competition from other facilities, and a slow decline in the flow of the spring led to the spa’s declining popularity, and it eventually closed.

Brunswick Square has Regency architecture on three sides – and on the fourth side the sea!

The Orient comes to Brighton in the exotic shapes of the Brighton Pavilion

‘Brighton comprises every possibility of earthly happiness.’ JANE AUSTEN

The gardens were subsequently taken over by George Albert Smith and he re-named them the St Anne’s Well Pleasure Gardens. The gardens included novelties such as demonstrations of hot air ballooning and parachute jumps, a monkey house, a fortune teller and a hermit living in a cave. There is no sign of the hermit as we pass through, but the park is full of people relaxing, chatting and generally being contented.

We saunter down through the wonderful green expanse of Brunswick Square – what more could you wish for than a beautiful garden to relax in, three sides of perfect Regency architecture, and on the fourth side the sea!

Embassy Court (1935) is an eleven-storey block of luxury Art Deco Modernist apartments, which were originally let to wealthy residents, including Max Miller and Terence Rattigan. Features such as enclosed balconies and England’s first penthouse suites made the building one of the most desirable and sought-after addresses in the country. The Modernist layout provided for levels of comfort and amenity that were exceptional for their day, including under-floor central heating, constant hot water, built-in electric fires and fitted kitchens with integral cookers and fridges. These were almost unheard-of innovations at the time.

Now we are on the true ‘tourist’ part of the trail, poking into the shops of West Pier Arches Creative Quarter, peering up as we pass the i360 observation tower (highly recommended for an all-round bird’s eye view), taking a step back in history at the Brighton Fishing Museum.

Brighton’s first pier was the Old Chain Pier (1823), used as a landing stage for cross-Channel passenger ships. Realising its commercial value, the owners began charging an entry fee of 2d and set up kiosks selling souvenirs as well as entertainment stalls. The Chain Pier was struck by many storms and eventually replaced by the Brighton Marine Palace & Pier (1899), which is what we see today, bustling in every corner with energy and pleasure.

Old Steine Gardens (1 hectare, 2.5 acres) was originally a natural drainage point, where the Wellesbourne River (now underground) met the sea. Local fishermen stored their boats and dried their nets here. In the late nineteenth century, as part of ongoing ‘improvements’, the area was drained and enclosed, and visitors began to use the Steine to promenade.

‘The beautiful thing about Brighton is that you can buy your lover a pair of knickers at Victoria station and have them off again at the Grand Hotel in less than two hours.’ KEITH WATERHOUSE

The Royal Pavilion (1787–1822) is a former royal residence. It was built in three stages, as a seaside retreat for George, Prince of Wales, who became the Prince Regent in 1811. The designer John Nash redesigned and greatly extended the Pavilion, and it is his work that can be seen today. The palace has an Indo-Islamic appearance on the outside, whilst the fanciful interior design is influenced by both Chinese and Indian fashion.

The seaside town had become fashionable through the residence of George’s uncle, Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland, whose tastes for cuisine, gaming, the theatre and fast living the young prince shared. And rather conveniently, his physician advised him that the sea water would be beneficial for his gout. The Royal Pavilion became his playground.

Next, we snake up Victoria Gardens (2 hectares, 4.9 acres), heading north along the line of the old river, at the bottom of a valley, steeper to the east than the west. We clamber up a steep flight of steps to Richmond Heights, which affords views back to the centre of the city.

We are heading for Queen’s Park (6.5 hectares, 16.1 acres), opened to the public in 1890. In the 1830s, Thomas Attree had acquired land to build a residential park surrounded by detached villas, inspired by Regent’s Park in London. Whilst the park itself materialised, with access by subscription, very little of the development did, other than an Italianate villa, which no longer exists. All that is left today, at the top of Tower Road, is the ‘Pepper Pot’ (1830), but no-one seems quite sure what it was originally for.

From the park, we take the exit immediately to the right of the tennis courts and head down Evelyn Terrace and then Bute Street, at the end of which we take some steps up to Whitehawk Hill. The hill is an ancient habitat designated a Local Nature Reserve, with areas of species-rich chalk grassland. From the top, we gaze down over the city and the sea, and can just make out the Isle of Wight, more than 65 km west.

The very first settlement in the Brighton area was here at Whitehawk Camp, directly opposite today’s racecourse stands, dating back to the Neolithic period. Archaeologists have found numerous burial mounds, tools and bones, suggesting it was a place of some importance.

Brighton Racecourse staged its first race in 1783; and according to legend, George IV, when still Prince Regent, invented hurdle racing nearby whilst out riding with aristocratic friends. They found some sheep pens which they proceeded to jump for a bit of fun. The racecourse was home for a while to top-class racing and was attended by fashionable society, but it drifted out of fashion when the prince and his friends lost interest. The course began to thrive again, however, with the arrival of the railway, which enabled London punters to have a day out at the races by the seaside.

Taking the tunnel under the racecourse, we come out into the patchwork-quilt landscape of Tenantry Down Allotments. The land was purchased by the council in the 1880s and has been used for allotments ever since.

Looking along the colourful Hendon Street towards Whitehawk Hill

Book yourself tickets on the i360 for incomparable panoramas

St Peter’s Church is a Charles Barry creation

The North Laines have a cornucopia of indie shops

The Extra Mural Cemetery (1851) occupies one of the most delightful spots in the whole of Brighton: a sheltered, gently sloping, well-wooded area of downland between two much steeper hills. As early as 1880, its potential as a green space as well as a burial ground was recognised when J.G. Bishop published a walking guide called Strolls in the Brighton Extra Mural Cemetery. What he first discovered, we experience too – the cemetery is a delight to walk through – headstones, more elaborate and ornate tombs and a Gothic Revival chapel, all within a leafy landscape of studied neglect.

Now we’re on the final leg of our journey. The Level (6.4 hectares, 15.7 acres) used to be open grassland, with two streams, the Wellesbourne and the Springbourne, converging here. Cricket was played here from the mid-eighteenth century, until 1822 when the space was formally laid out. It has recently been extensively restored, with a skatepark and children’s play area.

We stop at the Open Market, just to the west of The Level, reached through a multicoloured and inviting archway, for a snack and a drink. The original market, which had been on The Level itself, dates back to the 1880s when barrow boys began selling fruit and vegetables.

St Peter’s Church (1828), by Sir Charles Barry, is a fine example of the pre-Victorian Gothic Revival style. It was the parish church of Brighton from 1873 to 2007 and is sometimes unofficially referred to as ‘Brighton’s Cathedral’.

Finally, we head up Trafalgar Street to the North Laines, with the quaint mid-nineteenth-century Pelham Square on our left. ‘Laine’ is a Sussex dialect term for an open tract of land at the base of the Downs.

Ken Fines was Borough Planning Officer for Brighton in the 1970s. He is credited with having saved the North Laines area from extensive redevelopment that could have seen existing buildings being replaced by new high-rise buildings, a flyover and a large car park. An early pioneer for interesting, walkable, independent space in cities, I take my hat off to him. Today it is buzzing and full of indies, cafés and bars.