VICTO IAN INDUSTRY

Britain was the first country in the world to industrialise and our four featured cities were at the heart of this revolution.

Breakneck industrialisation led to a population explosion in these cities – growing sixfold over the nineteenth century – with chaotic urbanisation, few green spaces, little civic structure and extremes of wealth and squalor. The Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain (1842) pointed out that a typical country farmer lived twice as long (forty-one years) as a city shopkeeper (twenty years).

But from about this time a group of reformers begun to emerge, philanthropists and politicians who wanted to improve the lot of the city dweller through better sanitation and the provision of open spaces (or a city’s ‘green lungs’ as they were already being referred to, a term coined by William Pitt the Elder).

These men (the likes of Chamberlain in Birmingham, Baines in Leeds, Roebuck in Sheffield and Engels in Manchester) ‘did not argue on the defensive’, according to historian Asa Briggs. ‘They persistently carried the attack into the countryside, comparing contemptuously the passive with the active, the idlers with the workers, the landlords with the businessmen, the voluntary initiative of the city with the “torpor” and “monotony” of the village, and urban freedom with rustic “feudalism”.’

Non-conformism played a huge role in helping to transform cities. Non-conformists were behind many of the institutional initiatives of the nineteenth century – schools, libraries, parks and cemeteries. Furthermore, they were instrumental in campaigning for social and political reform that has subsequently formed the bedrock of modern civil liberties. You will see many fruits of their endeavours on our walks.

Today these cities are full of vitality and remain at the forefront of education and new service-based industries.

A CAN-DO ATTITUDE – ‘APPLY YOURSELF AND YOU WILL SUCCEED’

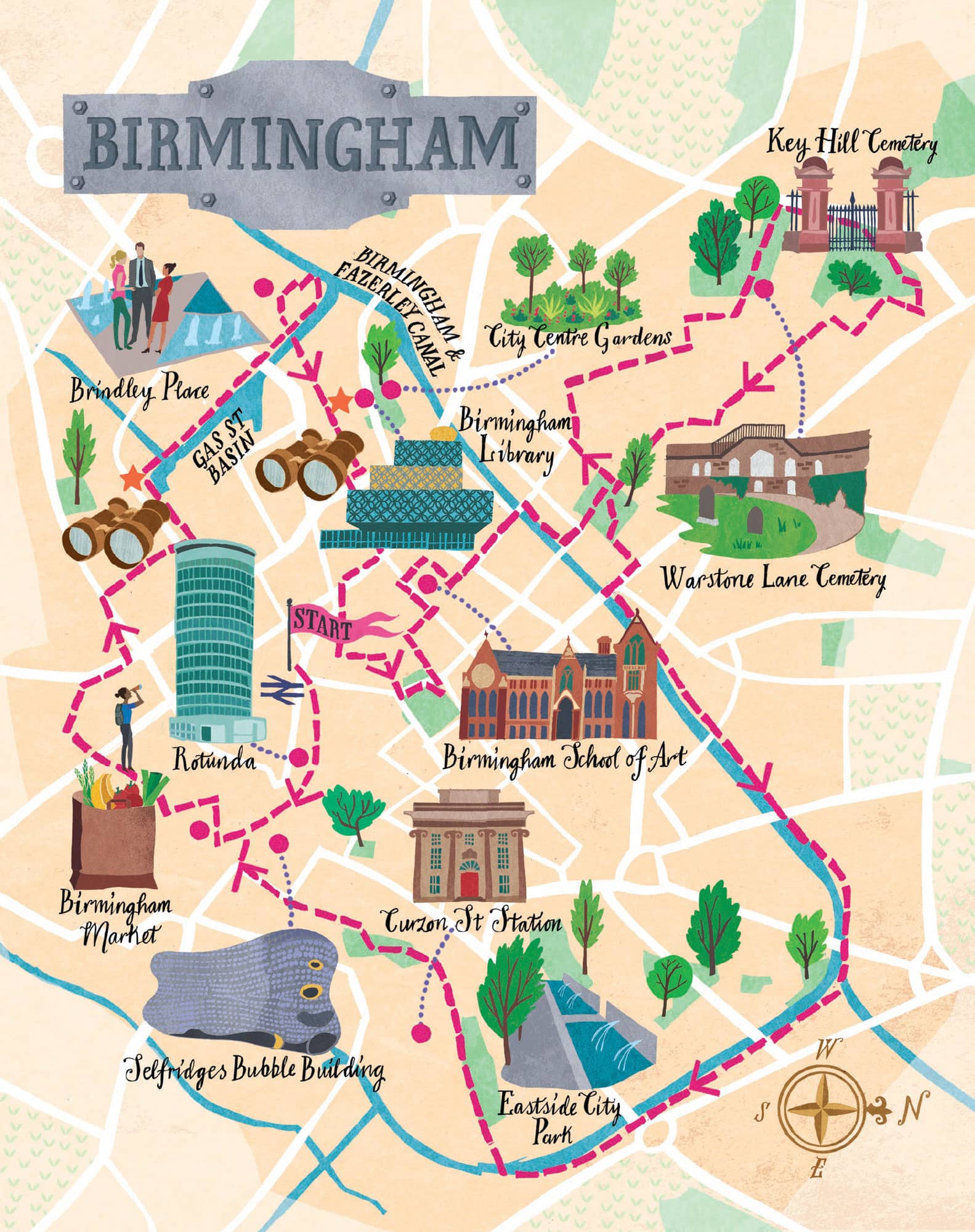

Birmingham

Birmingham was the epitome of the great city brought low by post-war planning that favoured the car and the shopping centre. The good news is that in the last decade Birmingham has managed to reverse many of its worst mistakes and a new, more walkable city is emerging from the rubble.

Birmingham’s early history is that of a remote and marginal area. It lay on the upland Birmingham Plateau and within the densely wooded and sparsely populated Forest of Arden. A medium-sized market town during the medieval period, it only began to gain commercial significance in the sixteenth century with the manufacture of iron goods.

Its key drawback was that it had no navigable river, and it wasn’t until the canals arrived that economic growth could take off. Within forty years the city was at the hub of the country’s canal networks and at the forefront of worldwide advances in science, technology and economic development. By 1791 it was being hailed as ‘the first manufacturing town in the world’. It had a distinctive economic profile, with thousands of small workshops practising a wide variety of specialised and highly skilled trades, encouraging exceptional levels of creativity and innovation.

The city also rose to national political prominence in the campaign for political reform, with Thomas Attwood and the Birmingham Political Union bringing the country to the brink of civil war during the Days of May that preceded the passing of the 1832 Great Reform Act. The Union’s meetings on Newhall Hill were the largest political assemblies Britain had ever seen.

The process of rebuilding after the bomb damage of the Second World War was led by the pragmatic Sir Herbert Manzoni, the City Engineer. His priorities were rehousing, civic redevelopment and sorting out traffic congestion. What he oversaw was to have a profound effect on the image of Birmingham in subsequent decades, with the mix of concrete ring roads, shopping centres and tower blocks giving the city its ‘concrete jungle’ tag.

By the 1980s the council and its planners finally realised that all was not well; and they set about improving the ‘liveability’ of the city, making it more appealing and ‘connected’ once again.

THE WALK

From the moment we step off the train, encapsulated by a gleaming new station full of light and space, we appreciate that Birmingham has been transformed. So very different from the grim 1960s warren of the old New Street station, deserved winner of the ugliest building in Britain award back in the day.

And the landmark Rotunda (1965) is a triumph of 1960s architecture brushed up for the twenty-first century. Listed Grade II, it has recently had the Urban Splash treatment, being converted from an office block into luxury apartments. And it’s a bit of a rarity in Birmingham, a building that has been re-purposed rather than knocked down and started from scratch.

As we approach the Bullring, we realise that things are really not the same at all – where I recall only a decade ago acres of concrete, impersonality and dull chains, now there are delightful walking spaces, punctuated by trees, statues, steps and water features; and then suddenly, on our left, the visual raucousness of the Selfridges (2003) ‘bubble wrap’ building.

Walking past St Martin’s, we reach the bustling Birmingham Market area. There have been markets here since the Middle Ages, and we feel sure that the liveliness of the traders and the breadth of food and non-food products today is as strong as it always was. A real joy of a market.

We walk under Holloway Circus past the rather incongruously situated Chinese pagoda. Wing Yip gave this pagoda to Birmingham as a gesture of thanks to the city for providing him with a home. He had arrived by boat from Hong Kong in 1959 at the age of nineteen with just £10 in his pocket. He opened a grocery store in Birmingham and, from these small beginnings, built a food empire that now supplies more than 2,000 Chinese restaurants around the country. Brummies, whether born and bred or incomers, seem to share a strong work ethic.

The Singers Hill Synagogue (1856) has played an important part in the lives of the Jewish community in Birmingham. There has been a Jewish community here since the thirteenth century.

The Mailbox is a good example of the building and rebuilding that has taken place in Birmingham over the decades. When it opened in 1970 as the Royal Mail sorting office, it was the largest mechanised sorting office in the country. Canalside wharves were demolished to make way for it and an underground tunnel connected it to New Street station. The building re-opened in 2000 as an upmarket development of offices, shops and restaurants.

The 25-storey Cube (2010), which we come to next, was designed by Birmingham-born Ken Shuttleworth, who co-designed London’s Gherkin building: ‘The cladding for me tries to reflect the heavy industries of Birmingham which I remember as a kid, the metal plate works and the car plants – and the inside is very crystalline, all glass; that to me is like the jewellery side of Birmingham, the light bulbs and delicate stuff – it tries to reflect the essence of Birmingham in the building itself.’

And now we reach the part of the canal where the vast majority of people who walk alongside the water are to be found, along the half-mile or so around Gas Street Basin, the centre of the network; now all beautifully restored, still carrying narrowboats and replete with restaurants and bars.

The Rotunda is a triumph of 1960s architecture brushed up for the twenty-first century

The Cathedral Church of St Philip is ‘a most subtle example of the elusive English Baroque’

Formerly derelict, the Brindleyplace development follows a Terry Farrell masterplan

‘It is an honour for me to be here in Birmingham, the beating heart of England.’ MALALA YOUSAFZAI

Brindleyplace’s central square is an agreeable open space with well-tended lawns and trees. Named after the eighteenth-century canal engineer, James Brindley, this district used to be a warren of factories but had lain derelict for many years. If you’re not into post-modern architecture (the overall master plan was laid out by Terry Farrell), you probably won’t warm to these buildings – they seem to lack a sense of time and place – but at least in terms of walkability, dwell time and community space the development is undoubtedly a success.

Next, we sweep over the canal footbridge, through the rather disjointed ICC building and out into the impressive Centenary Square, renamed in 1989 to commemorate the centenary of Birmingham achieving city status. Now we are in front of the new Birmingham Library (2013), designed by Dutch architect Francine Houben. In a similar way to the Cube, the exterior’s interlacing rings are intended to reflect the city’s canals and tunnels. ‘We see the circle as a motif of the city,’ Houben explains. ‘The façade recalls the industrial gasometers as well as the history of the jewellery trade here.’ The best bit for us is that we can do a ‘vertical walk’ through the library, ably assisted by a scintillating array of escalators. At the top, we gaze out from the Skyline Viewpoint, across the city and towards the many surrounding hills.

And then we relax for a few minutes in the City Centre Gardens (0.8 hectares, 2 acres), hidden away behind the library; attractive, well-planted, old-fashioned gardens that seem to be little known or visited.

Entering Chamberlain Square, the first building that grabs our attention is the ‘perfect and aloof’ Birmingham Town Hall (1834) atop its tall, rusticated podium. It was the first of the monumental town halls that would come to characterise the cities of Victorian England, and also the first significant work of the nineteenth century revival of Roman architecture, a style chosen here in the context of the highly charged radicalism of 1830s Birmingham with its republican associations.

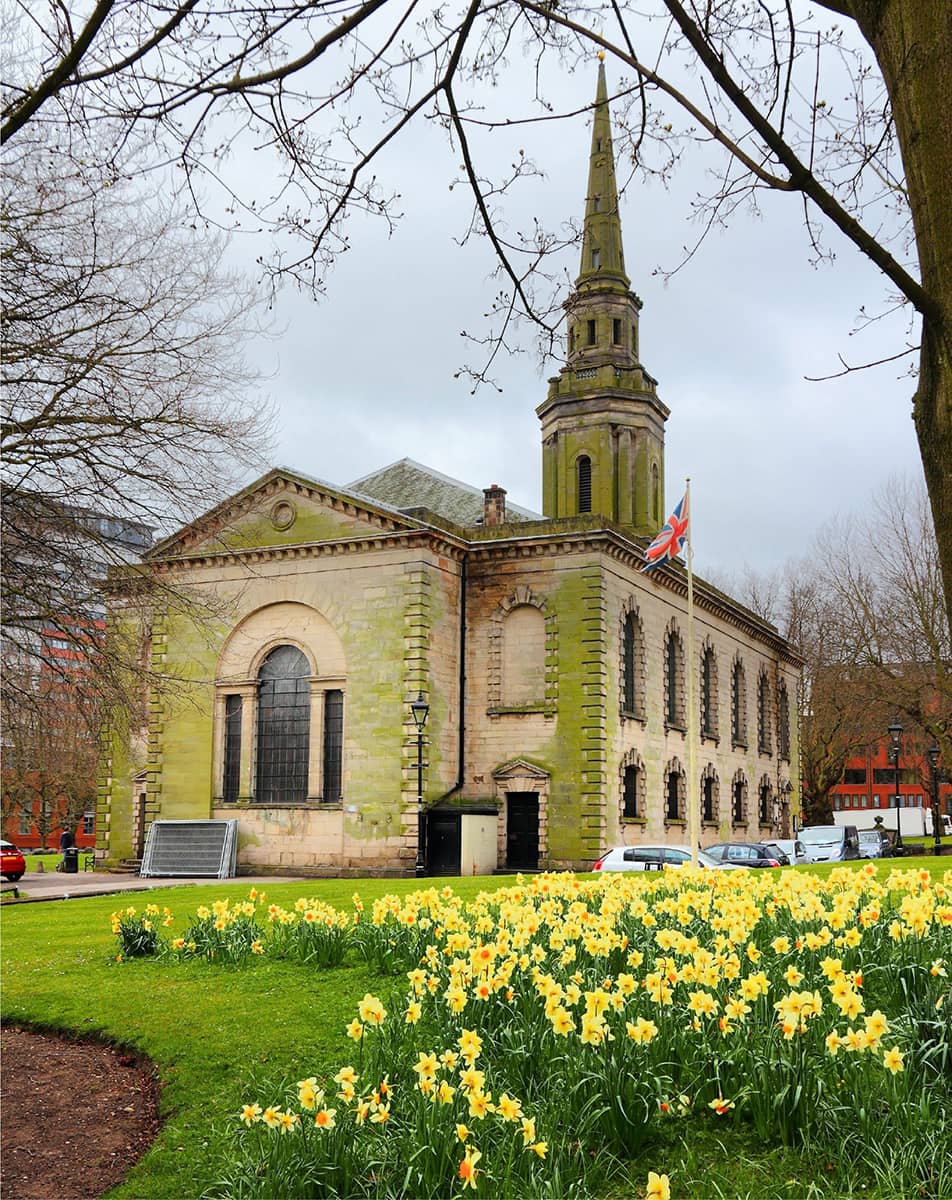

Now we reach the Cathedral Church of St Philip (1715) and its churchyard, a swathe of green in the middle of the city; in Alexandra Wedgwood’s words, ‘a most subtle example of the elusive English Baroque’. In 1884 it was enlarged in anticipation of its becoming a cathedral, which it did in 1905. At this time four stained glass windows were designed by Edward Burne-Jones, made by Morris & Company and installed in the chancel and at the west end.

We love Hudson’s Coffee House (1900) at 122 Colmore Row, designed in the Arts and Crafts style. Pevsner describes it as ‘one of the most original buildings of its date in England’. There are also several good buildings in upper Newhall Street, including the former Bell Edison Telephone Exchange (1896) on the corner of Edmund Street – a gorgeous terracotta building with beautifully decorated metal gates in the archway.

‘Birmingham, where they made useful things and made them well.’ LEE CHILD

Next, we take a little detour down Edmund Street towards the Bridge of Sighs to reach my favourite Victorian Birmingham building of them all, the Birmingham School of Art (1885), the first Municipal School of Art. Its Venetian style and naturalistic decoration are much influenced by John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice.

Morris and Burne-Jones had originally intended to join the priesthood, but in 1855, returning to Burne-Jones’s house in Bennett’s Hill after touring the cathedrals of Northern France, they decided instead to pursue careers in the visual arts, Burne-Jones resolving to become a painter and Morris an architect. The following day they discovered a copy of Malory’s Morte d ’Arthur in a Birmingham bookshop, which was to be one of their great inspirational works. They formed a group of fellow believers that became known as the Birmingham Set.

Arts and Crafts practitioners in Britain were critical of the government system of art education which was based on design in the abstract with little teaching of practical craft. This lack of craft training also caused concern in industrial and official circles, and in 1884 a Royal Commission recommended that art education should pay more attention to the suitability of design to the material in which it was to be executed. The first school to make this change was the Birmingham School of Arts and Crafts, a tradition which it carries on to this day.

Once across the ‘concrete collar’ of the ring road, we find ourselves in the attractive and unpretentious Jewellery Quarter. Birmingham’s Assay Office (1773) is still the busiest in the world today, hallmarking around twelve million items a year. The Jewellery Quarter has Europe’s greatest concentration of businesses involved in the jewellery trade and produces around half of all the jewellery made in the UK, employing over 6,000 skilled craftsmen; each workshop typically small-scale, employing between five and fifty people. In other words, Birmingham is still doing what it has always done so well, making specialised items in workshops.

The Birmingham and Fazeley Canal, a short stretch of which we take at this point, plunges down here through floodlit archways, undercrofts and narrow tunnels. It is an atmospheric link to the past in the middle of a modern city. In its industrial heyday, this Farmer’s Bridge Flight was a hectic place, kept open day and night, and lit by gas during the hours of darkness. There were said to be nearly seventy steam engines and more than 120 wharfs and works along the banks of the canal between here and Aston.

St Paul’s Square, which we approach next, was created in the late 1770s; it started out as an elegant and desirable residential location, but by the end of the nineteenth century had largely been taken over by workshops and factories, with the fronts of some buildings being pulled down to make way for shop fronts or factory entrances. The well-proportioned St Paul’s Church (1779) was the church of Birmingham’s early manufacturers and merchants – the engineers Matthew Boulton and James Watt had their own pews here.

The Arts and Crafts Birmingham School of Art is my favourite Victorian building in Birmingham

The restoration of the Birmingham canal system for leisure has been a planning triumph

The engineers Matthew Boulton and James Watt had their own pews at St Paul’s Church

‘Key Hill Cemetery is the most interesting place in the world to a Birmingham man.’ JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN

At the top of Vittoria Street, we admire the Birmingham School of Jewellery (1890). The Birmingham Jewellers and Silversmiths Association took the lead role in setting up the school, with the aim of promoting ‘art and technical education’ among apprentice jewellers. Take a look to see if there is an exhibition on: the students’ work is often displayed.

The splendid Chamberlain Iron Clock, which serves as a landmark for the Jewellery Quarter, was presented to local MP Joseph Chamberlain by his constituents in 1903. The Rose Villa Tavern, just behind it, has fine 1920s tiling and stained glass. After a quick refreshment here, we stroll down through the Warstone Lane Cemetery (1847). A major feature is the two tiers of catacombs, whose unhealthy vapours led to the Birmingham Cemeteries Act which required that noninterred coffins should be sealed with lead or pitch. Among several prominent Birmingham people buried here are John Baskerville, inventor of the eponymous typeface.

We trudge briefly alongside a dual carriageway and quickly escape through a pair of massive stone gateposts into the Key Hill Cemetery. This cemetery was set up in 1836 by a group of non-conformist businessmen concerned that free-church ministers were prevented from officiating at burial ceremonies in Church of England churches, and to meet the much-needed requirement for burial space.

We found out more about the cemetery from Margaret, a Friend of Key Hill Cemetery, one of those who had taken on the onerous, perhaps impossible, task of holding back nature; when we met her, she was in the process of unearthing some headstones that had been lost in the undergrowth. Notable burials include John Skirrow Wright, the inventor of the Postal Order; just beyond him, Alfred Bird, inventor of eggless custard; and squeezed between them, Joseph Gillott, a pen maker. Then we move on to the Chamberlain family headstones (just in front of the catacombs, on the left-hand end) and see what an extended and established family the Chamberlains had been in Birmingham. Next, we head along the base of the catacombs and see the headstone of scales manufacturer Thomas Avery (hard to say how much it weighed) and then Joseph Tangye, who helped launch Brunel’s steamship SS Great Eastern.

The splendid Chamberlain Iron Clock serves as a landmark for the Jewellery Quarter

We finally drag ourselves away from these fascinating histories and exit through the equally imposing gates on the north side; turning up Key Hill Drive, and then through an enclosed passage, at the end of which we are brought back with a jolt into the Jewellery Quarter.

We traverse St Paul’s Square again and re-join the canal at Livery Street; heading along it until we reach the Aston Junction, where the Digbeth Branch Canal terminates and meets the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal. The Spaghetti Junction of the nineteenth century, today it is mainly frequented by cyclists and the odd narrowboat.

Eastside City Park (2.7 hectares, 6.8 acres) is an urban park located alongside the Thinktank Birmingham Science Museum, on our way back from the canal to the city centre. Opened in 2012, it was the first new city-centre park in Birmingham created for more than 130 years. A sign hopefully that once again we understand the vital importance of green spaces within cities.

Directly to the south of the park is a space that looks ominously open, ready for ‘redevelopment’ as the HS2 terminus plonked alongside the new park. The good news is that the Grade I Curzon Street station (1838), the original terminus of both the London and Birmingham Railway and the Grand Junction Railway, hangs on doggedly to its site and will be a feature of the new station – a symbol hopefully of how much better Birmingham has become at mixing old and new.

The proposed HS2 terminal is a timely reminder as we approach the end of our walk of how vital transport communications are to the landlocked Birmingham; and that this could once again give it a massive advantage as it battles to remain ‘Britain’s second city.’

THE ORIGINAL NORTHERN POWERHOUSE

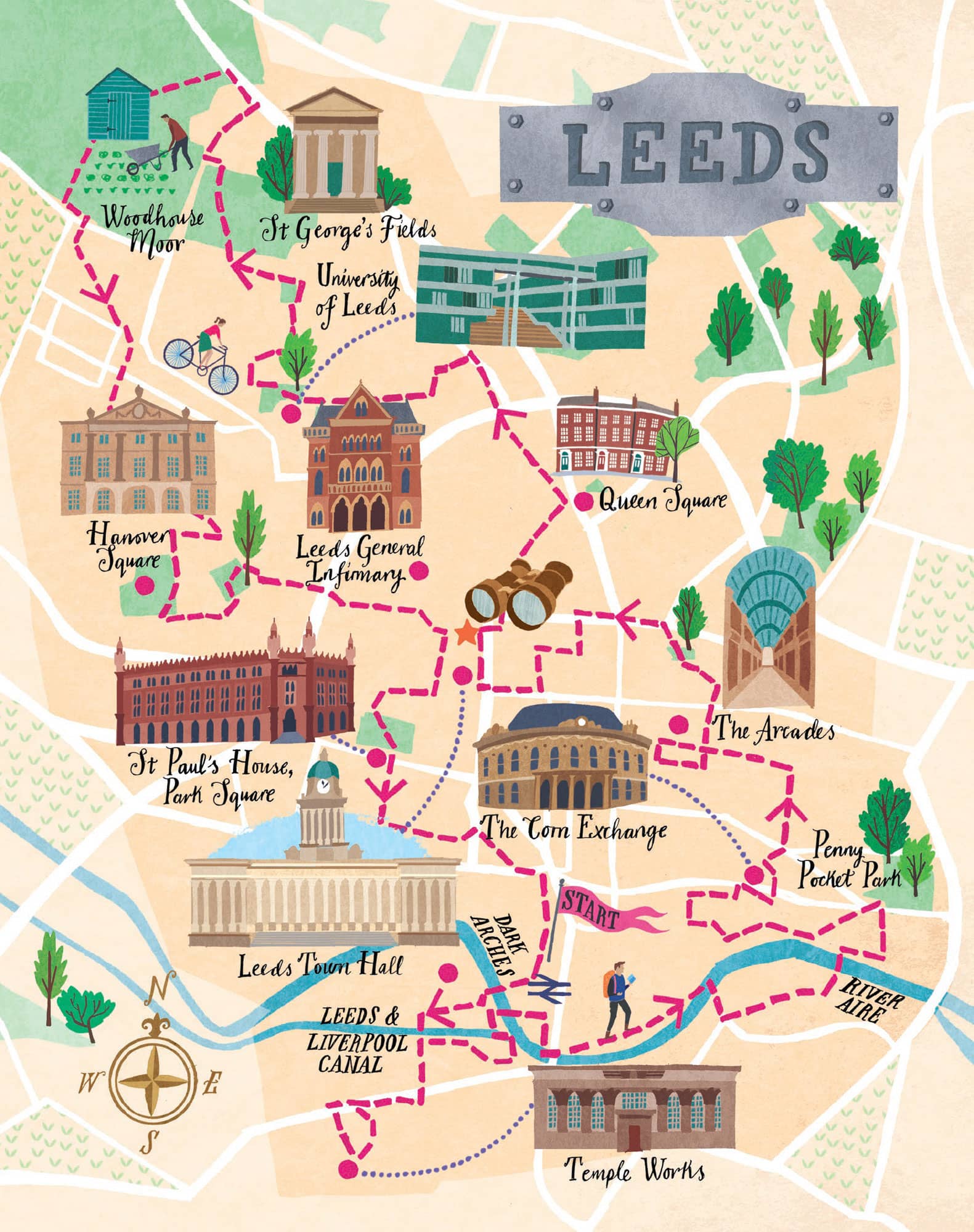

Leeds

Leeds is a city of industry and enterprise but also a very human-scaled town – this walk takes you through the old industrial areas, the retail district, the civic centre and the universities.

From being a compact market town in the valley of the River Aire in the sixteenth century, Leeds expanded and absorbed the surrounding villages as the industrial revolution swept all before it. But it didn’t expand at the helter-skelter speed of a city like Manchester, and this is reflected in a built environment that sits midway between a solid regional town and a booming city.

Leeds really came of age as a great city in the second half of the nineteenth century. The new Town Hall, admired throughout the Empire and a model for numerous other civic buildings, was opened by Queen Victoria in 1854.

In the 1920s, Leeds also became one of the first cities outside London to start to plan the way it was laid out rather than letting things happen willy-nilly. The Headrow was created as an east-west link between Mabgate and the Town Hall to relieve traffic congestion, to create a ‘planned’ civic route and get rid of slum housing; and the Outer Ring Road was also started.

Sadly, in common with most UK cities, it suffered much damage from the motor car in the 1960s, especially through the construction of the Inner Ring Road that severed the city centre from the university. But from the 1970s, things started to improve again, thanks to the leadership of John Thorp, City Architect from 1970 to 2010, widely lauded as the man who shaped modern Leeds. His philosophy was to examine and understand what already existed, looking for ways to improve or enhance it rather than sweep things away and bring in the new. He called the exercise ‘urban dentistry’.

In 2017 The Times voted Leeds as the number one cultural place to live in Britain, and in the same year Lonely Planet ranked it in the Top 10 best places in Europe to visit.

THE WALK

The New Station (1869) was built on arches that span the River Aire, Neville Street and Swinegate. Over eighteen million bricks were used during their construction – and the arches underneath became known as the Dark Arches. They have a cavernous and eerie feeling about them that takes you back in time – you half expect to bump into a Dickens character with a lantern around the next corner.

We cross the Hol Beck stream, which used to take a meandering path across the flood plain but now flows along a rather uninspiring culvert. Its waters were originally believed to have spa properties, but were then instead used to power the many mills that were built around here. On the other side, Holbeck Urban Village is a conservation area where many nineteenth-century industrial buildings survive in an unaltered group within the original street pattern.

Tower Works (1919) used to be a factory making steel pins for carding and combing in the textile industry. The design of its three extraction towers was heavily influenced by the owner’s love of Italian architecture and art. The largest and most ornate tower is based on Giotto’s Campanile in Florence; the smaller after the Torre dei Lamberti in Verona; and a third plain tower represents a Tuscan tower house.

As we head up Marshall Street, so we are confronted by what appears to be an Egyptian temple. This was the office building of the Temple Works (1841), built in the style of the Temple of Horus at Edfu by John Marshall who, in common with many other well-to-do gentry of the era, had a fascination for Egyptology and would also have been aware that flax, the source of his wealth, originally came from Egypt. When it was completed, it was one of the largest factories in the world, with two acres of factory floor employing over 2,000 workers and utilising 7,000 steam-powered spindles.

A curious feature of the building is that sheep used to graze on the grass-covered roof with its sixty-five conical skylights. The reason to have grass on the roof was to wick the moisture from the air to help retain the humidity in the flax mill, thus preventing the linen thread from becoming dried out and unmanageable.

Leeds Bridge (1879) is a rather fine Victorian cast-iron bridge. The east side bears the arms of the Corporation of Leeds (crowned owls and fleece). The western side has the names of civic dignitaries on a plaque. This was the original centre of Leeds and there has been a bridge here since medieval times and before that a ferry.

There has been a church on the site of Leeds Minster (St Peter’s) since the seventh century, but the one we see today is early Victorian Gothic (1841), and at the time the largest church built in England since St Paul’s. More importantly, it was the first great ‘town church’, intended to minister to the increasingly disillusioned working classes of the Industrial Revolution.

Penny Pocket Park (0.9 hectares, 2.2 acres) was once part of the old graveyard. It had stopped being used for burials by the 1830s as, like most urban churchyards, it was overflowing; a new cemetery was laid out in St George’s Field, where we walk later. But when the construction of the New Station began in 1866, it became clear that the route to Selby would need to pass through the old graveyard. It was agreed that the railway would be built on a solid embankment, with the gravestones on a slope, which makes for a rather curious sight.

Leeds is justly famous for its splendid shopping arcades

The former Corn Exchange has a Pantheon-style roof

The east side of Leeds Bridge bears the arms of the Corporation of Leeds

‘It always seems odd to come back to Leeds and to see people having wine with their meal and eating avocado pears. You want something on toast; you don’t want an avocado pear. This is Leeds!’ ALAN BENNETT

The Calls area, along with neighbouring Clarence Dock, served as docks on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the Aire and Calder Navigation throughout the Industrial Revolution and the early twentieth century. Today, many of the old warehouses have been renovated into pubs and restaurants, and if you’re feeling like refreshments this is a good place to pause.

Queen’s Court is an eighteenth-century house built for wealthy wool merchants; and a bit further along is Lambert’s Yard (1600), which boasts Leeds’ oldest surviving timber frame building.

Then on to one of Leeds’ most fabulous and unusual buildings, the Corn Exchange (1863), designed by Leeds’ favourite architect Cuthbert Brodrick, best known for Leeds Town Hall. He took as his model the Halle au Blé in Paris, built in the 1760s, but we can’t help but be reminded of the Royal Albert Hall.

Now we really are in the commercial heart of the city, and next up is Kirkgate Market, the largest covered market in Europe. It first opened in 1822 as an open-air market, and between 1850 and 1875 the first covered sections were added. In 1884, it was the founding location of Marks & Spencer which opened here as a penny bazaar.

The 1904 hall is the most ornate of the halls and is situated at the front, the route we take. It has a grand Flemish-style frontage with Art Nouveau details – shop fronts below, offices above and an extravagant skyline of towers, turrets and chimneys. Behind this amazing façade is an even more striking market hall with clustered cast-iron Corinthian columns supporting a central octagon. Somehow, this old-fashioned market has survived the onset of out-of-town malls and is full of life, hosting 800 stalls and typically having more than 100,000 visitors on a Saturday.

The Arcades are one of Leeds’ great joys, bustling and busy with shoppers. They were built around 1900 and designed in ebullient style by the theatre architect Frank Matcham. The exteriors are mainly of faïence from the Burmantofts Pottery, and the interiors contain several mosaics and plentiful use of marble. They were built to appeal to the affluent middle-class as a safe and clement place away from the hustle and bustle of the grimy streets. The fashion for arcades spread right across the country during this period.

St John’s (1634) is the oldest church in the city, built at a turbulent time when very few churches were constructed. The glory of the church lies in its magnificent Jacobean fittings, particularly the superb carved wooden screen.

Merrion Gardens (0.3 hectares, 0.7 acres) was originally laid out as a memorial to Thomas Wade who, in 1530, left a will that stipulated that the money be used to benefit the people of Leeds. Often full of lunch-breakers relaxing in the sunshine, it seems his money was well spent.

Next, we walk past the Leeds Art Gallery and look ahead of us to see the Leeds Town Hall (1853), Cuthbert Brodrick’s most famous work, and opened in great pomp and ceremony by Queen Victoria. It became a model for civic buildings across Britain and the British Empire.

Millennium Square is one of those ‘prairie’ squares which has been left ‘intentionally blank’ so that lots of events, festivals and fairs can take place there; but when there is nothing going on, it looks rather … empty. It was Leeds’ flagship redevelopment project to mark the year 2000. Just to the south are the pocket-sized Nelson Mandela Gardens.

Leeds Civic Hall (1933) is the work of Vincent Harris, best known for his work on the Exeter University campus (see our Exeter walk). This was in the depths of the Great Recession and the building was used as a piece of Keynesian job creation to stimulate the economy. I love the golden owl sculptures, the emblem of Leeds. It’s surprising to discover that they were in fact added only in 2000 by John Thorp, the much-respected City Architect, based on a pair of originals on the roof.

Before we head to the two universities, we can’t resist a short ‘green space’ diversion to the close-by Georgian Queen Square, built between 1806 and 1822, each house originally having access to warehouses and workshops at the rear. Late-nineteenth-century gas lamp posts with fluted shafts complete the scene. It is an architectural oasis in this part of town, but that doesn’t detract from its charm and tranquillity.

The university campuses

The impressive Broadcasting Tower (2009) on the Leeds Beckett campus is clad in weathering Corten steel, which intentionally makes it look as if it is rusting away (the Angel of the North is made of the same material). I love this building.

The University of Leeds campus is, in the words of Maurice Beresford, ‘a free open-air museum of architectural and social history’. It comprises a mixture of Georgian, Gothic Revival, Art Deco, Brutalist, Postmodern and eco-buildings, making it one of the most architecturally diverse university campuses anywhere in the country.

In the heart of the campus, Chancellor’s Court is a little green haven. Its architects likened it to the great Oxbridge quadrangles, but to my mind, it has more life, intimacy and interest. It is beautifully landscaped with trees and plants dotted around the square and two huge rock features.

As we stroll uphill past the Edward Boyle Library, we soon reach the old heart of the university, Alfred Waterhouse’s wonderful Great Hall of 1894. Then we head left into St George’s Fields (3.8 hectares, 9.3 acres), which served as Leeds’ General Cemetery from 1835, when St John’s Churchyard became full. There is an elegant Greek Revival Gatehouse and non-denominational temple. Again, another lovely tranquil spot much used by students.

The Leeds Civic Hall was built in the 1930s as part of a Keynesian make-work scheme

These allotments on Woodhouse Moor were started to support the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign

Woodhouse Square was laid out in the 1840s as part of a gentrification scheme

‘People do not realise that many of my works are done in urban places. I was brought up on the edge of Leeds, five miles from the city centre - on one side were fields and on the other, the city.’ ANDY GOLDSWORTHY

Woodhouse Moor (26 hectares, 64 acres) is now a park, but it wasn’t always so; it was once part of a much larger moor of the same name. High above Leeds, it has been a military rallying point, and Rampart Road (on the north-east side) is named after the ramparts which were once there. During the English Civil War, Parliamentary forces led by Thomas Fairfax massed on Woodhouse Moor before taking Leeds from the Royalists. In the nineteenth century there started to be ‘encroachments’ upon the moor; parts of the land were being parcelled off for development, and rumours circulated that a substantial section might be given over to the army as an encampment. A grassroots campaign in support of a public park gathered momentum and in 1857 the park was acquired by the council to improve public health in the city. It has often been referred to as ‘the lungs of Leeds’. By the end of the nineteenth century, the moor was used for a wide variety of purposes, including sport, musical concerts and political meetings. The allotments that we pass on our right, incidentally, are survivors from the Second World War, when the park was put to productive wartime use growing vegetables.

We head right up the cobbled Kendal Lane, which had been an ancient pre-turnpike road that climbed the hill towards Great Woodhouse Moor. Behind the brick wall on our left is Claremont House (1772), from whose grounds Hanover Square was subsequently created.

Continuing along Kendal Lane, we soon spot Hanover Square down the slope to our left. First, though, we pass the impressive Denison Hall (1786) which was built in just 101 days according to the blue plaque! However, it proved a difficult house to sell as, in the words of the Leeds Guide of 1806, it was ‘too large for a man of moderate fortune, and too near the town to be relished by a country gentleman’. In 1823, Hanover Square was created in the extensive gardens of the house with the hall at the north side, in an attempt to bring harmony and make a buck or two. But it was never fully realised, simply because the developers underestimated the reluctance of well-to-do families to live so close to industry (they mostly preferred the leafy Headingley).

The Leeds General Infirmary, like St Pancras station, was designed by George Gilbert Scott

Park Square is Leeds’ green gem

Woodhouse Square was laid out in the 1840s by John Atkinson with a similar intention, but likewise was never fully completed. The sloping central garden became a public park in 1905.

For the last leg of our walk, we cross back over the ring road to be greeted by one of the most scrumptious buildings in Leeds, the old Leeds General Infirmary (1869). And yes, if it conjures up St Pancras station in your mind there is a reason … it is by the same architect, George Gilbert Scott, and dates from the same period.

Park Square was laid out in 1788. It is the most attractive piece of green space in the city centre, so we pause and enjoy it. On the south side is St Paul’s House (1878), built by Thomas Ambler in an ornate Hispano-Moorish style as a warehouse and cloth cutting works, complete with minarets. So much more appealing than your typical warehouse or factory today.

Bank House (1969) at the junction with King Street is an architecturally adventurous example of the Bank of England’s 1960s building program, designed by BDP architects as an inverted ziggurat in grey granite. What appear to be balconies on the first floor are actually remnants of the 1960s plan to connect the whole city via a network of elevated pedestrian skywalks that (fortunately in my opinion) never materialised.

Just on our right at this point is the sumptuous Hotel Metropole (1897), designed in what Pevsner describes as ‘undisciplined French Loire taste’. You’ll understand what he means when you see it! Inside, giant columns and a bronze-panelled staircase evoke the extravagance of late Victorian Leeds.

City Square was laid out from 1893 in grand style to celebrate the granting of city status. The Old Post Office (1896) was built by Sir Henry Tanner and was Leeds’ largest post office and also served as the city’s telephone exchange. The Queens Hotel (1930s) has played host to many famous guests including Laurel and Hardy.

Going back through the station, we see perhaps the best bit of it – the stylish 1938 Art Deco North Concourse with wide concrete arch crossbeams.

‘WHAT MANCHESTER DOES TODAY, THE REST OF THE WORLD DOES TOMORROW’

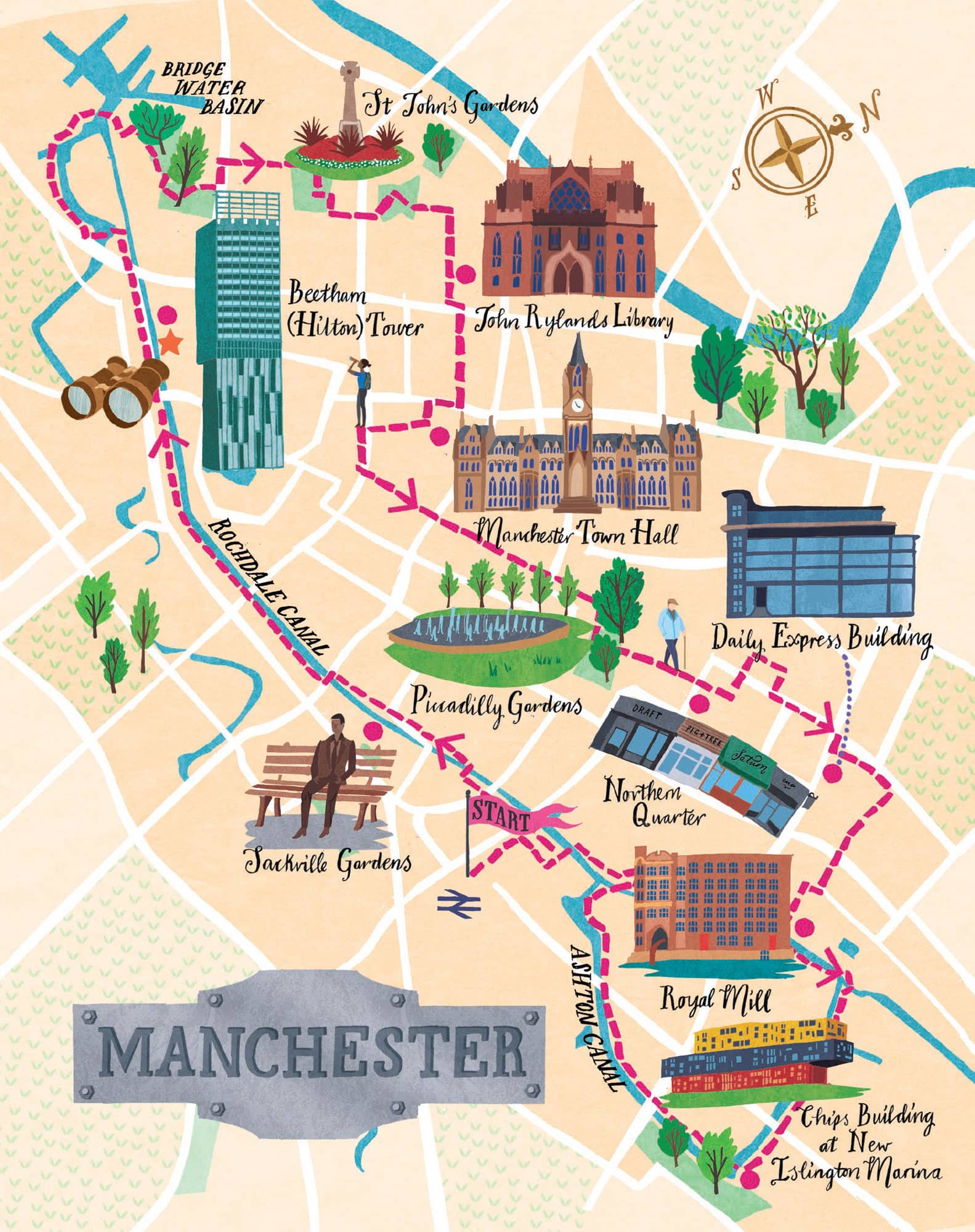

Manchester

There is more social and cultural history per square inch of a walk in Manchester than in just about any other city – but we have to rely on the canal to provide our ‘greenway’.

Manchester lies in a bowl-shaped land area bordered to the north and east by the Pennines, and to the south by the Cheshire Plain. This low-lying city is on the confluence of three rivers – the Irwell, the Medlock and the Mersey; the latter of which, via the Manchester Ship Canal, gives access to the sea. Its geographic features were highly influential in its early development as the world’s first industrial city – its climate, proximity to a seaport, the availability of water power and its nearby coal reserves.

Manchester perhaps more than anywhere else is a product of the Industrial Revolution and is widely regarded as the first modern, industrial city. It is synonymous with warehouses, railway viaducts, cotton mills and canals – remnants of a past when the city principally produced and traded goods. Manchester has minimal Georgian or medieval architecture, but a vast array of nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings.

Cotton made Manchester and, in Asa Briggs’ words, it was the ‘shock city of the industrial revolution’ – witnessing unplanned urbanisation, a focus on money-making, extremes of wealth and squalor, an exploding population, little civic structure until the mid-nineteenth century but at the same time formative social values. It was always perceived as a ‘modern city’ and full of vitality – qualities which it exhibits just as strongly today.

Manchester was also a bastion of radicalism and non-conformism. It was here in 1819 that the Peterloo Massacre occurred among a large crowd campaigning for better parliamentary representation. And it was the city where Engels met Marx in 1845 and started to write the Communist Manifesto.

Today, Manchester is rated as one of the UK’s most creative cities, and this walk makes it evident why, passing by art galleries and eclectic independent shops and food outlets: buzz and creativity fill every corner.

THE WALK

We set out from Manchester Piccadilly station (1842) and just before the Dale Street bridge we drop down right to join the Rochdale Canal (1804) at Lock 85. The canal has great charm and intrigue as it passes right through the heart of the city, under buildings on huge concrete stilts, in a part known as the Undercroft. We feel like urban invaders stealing up unannounced on the city. But there are quite a few people who sleep here rough, so you probably don’t want to be on your own or walking through in the dark. The nine locks between here and the Bridgewater Basin are known as the ‘Rochdale Nine’ and they follow in fairly quick succession one after the other.

Coming out of the Undercroft, we find ourselves in the Gay Village quarter. With the decline of the canal, the area became a well-known ‘red light’ district and also a place for gay men to meet clandestinely. The turning point to putting the area on the map was the opening of Manto in 1990, an openly gay bar with large plate glass windows that declared no-one was trying to hide anymore.

On the south side of the canal we pause a moment in Sackville Gardens (0.5 hectares, 1.2 acres), which has a memorial to Alan Turing, sitting on a bench. The cast bronze bench carries the motto ‘Founder of Computer Science’ as it might appear if encoded by an Enigma machine: ‘IEKYF RQMSI ADXUO KVKZC GUBJ’ (although arguably it should change every day!). The park was chosen because, according to one pundit, ‘It’s got the university science buildings where he worked after the war on one side, and all the gay bars on the other.’

The Beetham Tower (2006) is a landmark forty-seven-storey mixed-use skyscraper, described as ‘the UK’s only proper skyscraper outside London’. In a short space of time, it has become an iconic building, featured in the opening titles of several television programmes, including Coronation Street.

After Deansgate, we reach Castlefield. History books are often wont to say that the arrival of the Bridgewater Canal here in 1761, linking the Duke of Bridgewater’s mines at Worsley to the centre of the city, marked the start of the Industrial Revolution, halving the price of coal and making steam power commercially viable.

We follow the basin round to the gleaming white sickle-shaped Merchant’s Bridge (1995) that spans the main canal basin opposite Barca Bar. Then we head under the railway lines and take the next right to the Roman Fort of Mamucium, established around AD 79. The fort was sited on a sandstone bluff near the confluence of the Medlock and Irwell rivers in a naturally defensible position.

Up next is the Museum of Science and Industry. Among many interesting exhibits, it incorporates the world’s first railway station, Manchester Liverpool Road (1830). Apparently, the railway was so keen to attract genteel travellers that it offered flat trucks on which private coaches could be loaded, occupants, horses and all.

I like the little park we wander into next – St John’s Gardens (0.6 hectares, 1.5 acres) – which is one of very few green spaces in the city centre. And even that’s really more by mishap than design, as this was formerly the site of St John’s Church (1769), demolished in 1931 after a long period of neglect. Today a stone cross stands in the gardens to commemorate the church and the 22,000 souls that lie buried in the graveyard. Among them is John Owens, founder of Owens’ College, the forerunner to the University of Manchester.

We leave the gardens by what was the original gate to the church. Opposite we see St John Street, in which the majority of the houses are listed – it is the only Georgian part of the city that still survives – occupied now by solicitors, accountants and medics.

Walking up Byrom Street, we pass the Cobden House (1770s) on our left. This was originally the home of Richard Cobden, prominent entrepreneur, politician and member of the Anti-Corn Law League. It was bought by John Owens in 1851 to fund the establishment of Owens College, which was on this site until 1873 when it moved to a new home on Oxford Road, today the University of Manchester.

Now we enter one of the newest parts of the city, Spinningfields, which was re-developed in the 2000s as a business, retail and residential area. We stroll through Hardman Square (0.5 hectares, 1.2 acres), and soon our eyes alight upon one of Manchester’s finest modern buildings, the Manchester Civil Justice Centre (2007), named one of the ‘Best British Buildings of the twenty-first century’ by Blueprint magazine.

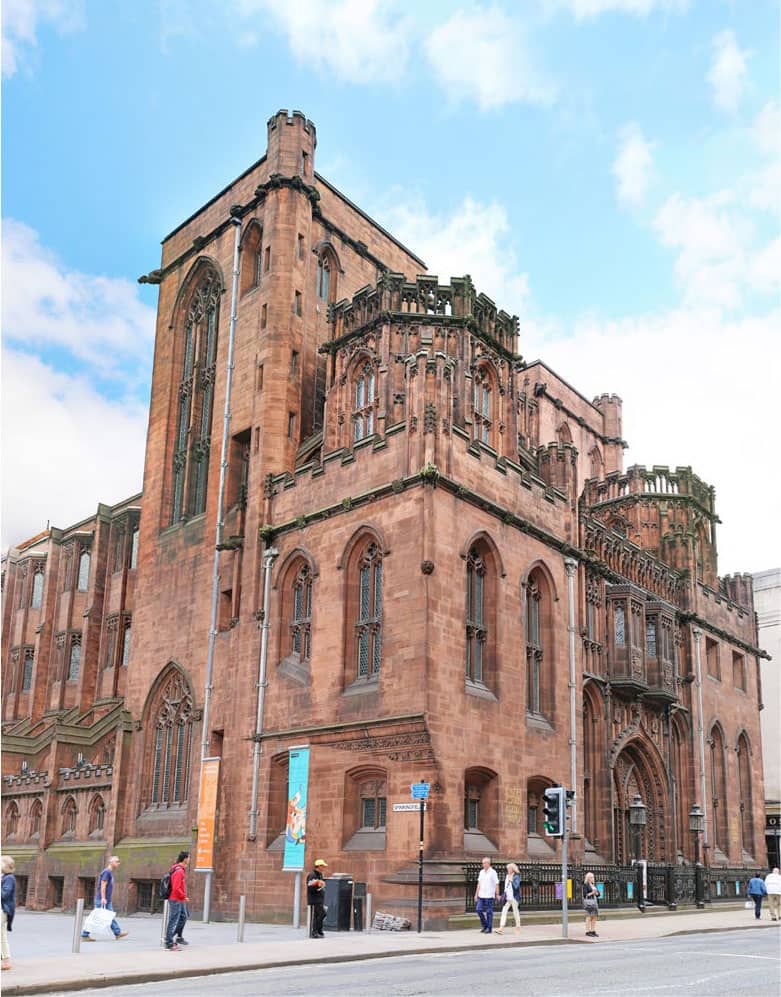

The John Rylands Library (1900) is one of Manchester’s great late-Victorian neo-Gothic buildings, full of Arts & Crafts touches. It was designed by Basil Champneys, best known for his work designing Oxbridge colleges. Inside, it looks like a cathedral filled with books, and houses one of the world’s finest collections of rare books and manuscripts, including a first edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. John Ryland was one of the wealthiest and most successful Manchester cotton barons of his era.

We head down the pedestrianised Brazennose Street, past the Lincoln statue, arriving at the grandeur of Albert Square and the iconic Manchester Town Hall (1877) looming large in front of us. Designed by Sir Alfred Waterhouse, it’s one of the finest examples of Gothic Revival architecture in the world.

Facing St Peter’s Square, the Manchester Central Library (1934) was designed by Vincent Harris. The form of the building, a columned portico attached to a rotunda-domed structure, is loosely derived from the Pantheon in Rome. It was the successor to the Manchester Free Library (1852), the first ever public lending and reference library in the country. Alongside the library is the grand Midland Hotel (1903), designed by Charles Trubshaw in a highly individualistic Edwardian Baroque style. The Free Trade Hall (1856) – now the Radisson Blu Hotel – in Peter Street was an important meeting place in the long campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws.

St Peter’s Square was the scene of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre when cavalry charged into a crowd of nearly 80,000 that had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation. Fifteen people were killed, and many hundreds injured. On the far side of the square, alongside the tram route, is the Manchester Art Gallery (1824), built by Charles Barry in the Greek neoclassical style. The gallery has a good collection of Victorian art, especially the Pre-Raphaelites and Victorian decorative arts.

The Museum of Science & Industry very much merits a visit

St Peter’s Square was the scene of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre

The John Rylands Library is one of Manchester’s great late-Victorian buildings

The Daily Express Building was an inspiration to the young Norman Foster

The Northern Quarter is a Mecca for independent, quirky shops, bars, and cafés

‘Manchester is in the south of the north of England. Its spirit has a contrariness in it.’ JEANETTE WINTERSON

Piccadilly Gardens (0.8 hectares, 1.9 acres), in many people’s eyes the ‘heart of the city’, started life, like almost all the open space in the city centre, as reclaimed land. It ended up being the largest green space in the city centre, originally looking very much like a traditional city park with flower borders and wooden benches. In 2002, however, it was reconfigured with a water feature and concrete pavilion by Japanese architect Tadao Ando. The pavilion wall is soon to be removed – people never warmed to it and it became known as ‘Manchester’s Berlin Wall’. While the space works admirably as a place of congregation, market stalls and as a transport hub, I miss the traditional flower borders and it lacks a sense of repose.

Incredible as it might seem walking through it today, in the 1840s the Northern Quarter was the centre of one of the most significant economic changes in history, with the Industrial Revolution at full throttle and Manchester taking its place as the world capital of the textile industry. It was the spot where Manchester’s first cotton mill was opened by Richard Arkwright in 1783. Within seventy years, there were 108 mills in this central area.

Today the Northern Quarter is a mecca for independent, quirky shops, bars, and cafés … and a magnet for alternative and bohemian culture. We take a look round the Richard Goodall Gallery, one of the UK’s largest commercial galleries; and further along Oak Street, we discover the Manchester Craft and Design Centre, formerly a Victorian fish and poultry market.

Emerging from the Northern Quarter and crossing the busy Great Ancoats Street, we marvel at the Daily Express Building (1939), designed by engineer Sir Owen Williams in Futurist Art Deco style, with horizontal lines and curved corners, clad in a combination of opaque and vitrolite glass. It was considered highly radical at the time and incorporated curtain walling, an emerging technology. Norman Foster admired it very much in his youth and now lists it as one of his top five favourite buildings in the world.

As we head down Cornell Street, so we enter the Ancoats quarter. We are puzzled by the name of a street – Anita Street – which seems out of place with the other street names here. Anita Street, it turns out, was originally called Sanitary Street, part of a project by the Sanitary Committee of the Corporation in the 1890s to improve the quality of housing and hygiene. The ‘S’ and ‘ry’ were discretely dumped in the 1960s when ‘sanitary’ became less a badge of honour and more a taint of municipalism.

Our source of this information was Toni, a talkative local of Italian descent; he also describes to us how, when he had been born here the area was still known as ‘Little Italy’ and was full of Italian families, many of whom were in the ice cream trade, which they then dominated in the city. At its peak, the population of Italians in Little Italy was over 2,000.

The ‘Chips’ building was inspired by … chips!

The canal system is a big feature of this city, seen here with the iconic Beetham Tower

Canal Street is the centre of the Gay Village quarter

Ancoats at the height of the Industrial Revolution boasted the biggest concentration of mills anywhere in Europe. Royal Mill (1912) is one of many restored mills that collectively comprise the best and most-complete surviving examples of early large-scale factories concentrated in one area. We wave goodbye to Toni on the ‘Ponte Vecchio’ bridge as he calls it (notice its shape) and then head east along the southern side of the Rochdale Canal.

The New Islington Marina comes up soon on our right, including a new public eco-park called Cotton Field. It consists of a new body of water, a boardwalk, an ‘urban beach’ and distinctive islands. Extensive planting includes an orchard island, a grove of Scots pines, and wildflowers and reed beds. Just to the south of here is the New Islington Project, developed by Urban Splash, which includes the famous Chips (2009) development. Will Alsop, the architect, offered the following honest assessment of his inspiration: ‘My inspiration was chips! Three fat ones to be precise, stacked on top of each other.’ This building is pure fun.

On our way back along the Ashton Canal we cross the Store Street Aqueduct (1798), built by Benjamin Outram on a skew of forty-five degrees across Store Street, and believed to be the first major aqueduct of its kind in Great Britain and the oldest still in use today. We re-join the Rochdale Canal at Piccadilly Basin.

Dale Street Warehouse (1806), on the north side of the Rochdale Canal, is the only stone-built canal warehouse in Manchester, using Pennine Millstone Grit stone brought down from the moors. It has four shipping arches at ground level that once opened onto the water of the canal, so goods could be loaded and deposited. We walk through the Archway of the Bridgewater Basin and turn left along Dale Street to complete our walk.

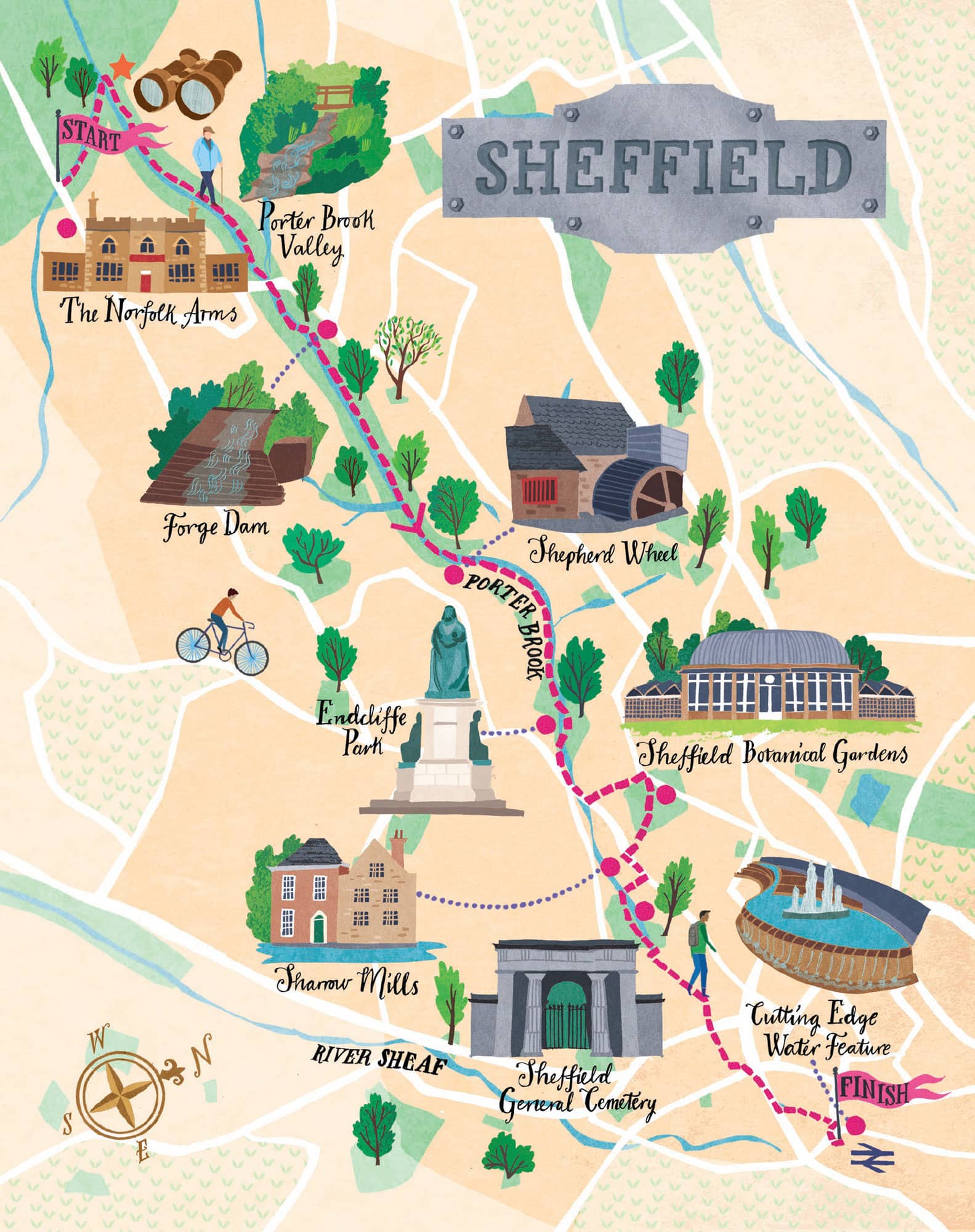

SHEFFIELD’S LIFEBLOOD THRUSTING LIKE A BLADE INTO THE CITY

Sheffield

This is a simply unbelievable walk that propels you onwards and downwards from the ruggedness of the moors to the heart of Sheffield in six gripping miles of stream-side rambling and culvert hugging.

The city nestles in a natural amphitheatre created by seven hills and the confluence of five rivers: The Don and its four tributaries the Sheaf, Rivelin, Loxley and Porter. Consequently, much of the city is built on hillsides with views into the city centre or out towards the countryside. Nearly two-thirds of Sheffield’s entire area is green space, and a third of the city lies within the Peak District National Park. There are more than eighty-eight parks and 170 woodlands and over two million trees, giving Sheffield the highest ratio of trees to people of any city in Europe.

The villages around Sheffield were established as centres of industry and commerce well before the onset of the Industrial Revolution, utilising the fast-flowing rivers and streams that brought water down from the Peak District. The valleys through which these flowed were ideally suited for man-made dams that could be used to power water mills, the remains of several of which we see on this walk. This facilitated Sheffield’s move into cutlery and steel production, in which it became pre-eminent in the nineteenth century as a result of Benjamin Huntsman’s invention of the crucible technique for making exceptionally high-quality steel, which for decades gave Sheffield the edge over other steel-producing cities.

The city centre lies where these rivers and valleys meet. The city has expanded out along and up the valleys and over the hills between, creating leafy neighbourhoods and suburbs within easy reach of the city centre. Each valley that stretches out from the city centre has its own character, from the densely industrial Don Valley in the north-east, to the green and cosmopolitan residential streets around the Ecclesall Road on the Porter Valley to the south-west.

THE WALK

The moment we get into the taxi at Sheffield station on our way up the hill, we are reminded that we are in a city famous for its music. As we pull away from the rank the light flashes on in the door – ‘Red Light Indicates Doors are Secure’ – the name of a favourite Arctic Monkeys song.

The incredible thing about Sheffield is how quickly we get out of it, which is even more surprising if you consider it’s one of the largest cities in the UK. Within five minutes, we are on the Ringinglow Road and the ancient taxi is labouring up the hill like a shire horse, one minute huffing past Victorian mansions and the very next chugging past sheep and a traditional Peak District Farm, complete with sheepdogs and untidy yard.

We alight at the Norfolk Arms, an old coaching inn which is now a popular place for walkers to stay to explore the Peak District National Park on its doorstep. We, however, set out north east along the Fulwood Lane to the head of the Porter Brook Valley.

The Porter Brook derives its name from its brownish colour, similar to the colour of Porter beer, a discolouration obtained as it passes over iron-ore deposits. Like the other rivers in Sheffield, the Porter Brook is ideally suited for providing water power, as the final section falls some 135 metres in a little over 2.5 km. This enabled dams to be constructed reasonably close together, without the outflow from one mill being restricted by the next downstream dam.

By 1740 Sheffield had become the most extensive user of water-power in Britain. Ninety mills had been built, two-thirds of them for grinding. In the Porter Valley alone twenty-one mill dams served nineteen water-wheels, mostly used for grinding corn, operating forge-hammers and rolling mills, grinding knives and the various types of blades that made Sheffield famous.

Nowadays, of course, the Porter Brook’s role has changed – it is used to expend energy rather than harness it. During our steady descent, we pass many people walking, jogging or cycling; for the Porter Brook is truly a city escape nowadays, offering the rural idyll of a small, fast-flowing stream in a narrow, verdant valley.

The first such spot we came to is Forge Dam (1765) which was used for the production of saws. Today the café is a popular spot for Sheffield families walking up the valley or bringing their toddlers to play in the playground here.

Next, we come to the Shepherd Wheel, which first started generating power way back in the 1550s, became derelict and was then lovingly restored by the Friends of the Porter Valley, who have reopened it as a working museum. We are left spellbound watching the water feed into the mill wheel, turning the axles, the crown wheel, the pinions, the drums, the belts, the lion shaft, all finally connecting up with the grind stones. The atmosphere today is mellow, with the soft and agreeable rumbling of the wheels; but during its working life there would have been all sorts of health and safety risks, from silicosis to exploding grindstones, making it a very hazardous place to work

We continue down to Endcliffe Park (15 hectares, 37 acres), a delightful space opened in 1887 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Near the entrance is a statue of her and midway up the path towards Whiteley Woods is an obelisk also in her honour. The park was laid out by William Goldring, a nationally acclaimed park designer, who was responsible for work on nearly 700 different garden landscape projects across England and was in charge of the Herbaceous Department at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew.

The Sheffield Botanical Gardens are a delightful spot for a wander

The inscriptions at Sheffield General Cemetery reveal so much about Sheffield’s past citizens

‘Sheffield is the greenest city in the EU, by a long chalk. We’ve got two and a half million trees, 250 parks and wetlands and a third of the city is in the Peak District.’ RICHARD HAWLEY

From the Ecclesall Roundabout onwards into the city, the character of the Porter Brook changes substantially as it plays second fiddle to the urban landscape. It becomes confined and increasingly culverted as it heads towards the city centre. If you enjoy topographical detective work, you will relish the search for it.

The 1830s saw a wave of philanthropic activity in this part of Sheffield, as newly wealthy non-conformist industrialists sought to make their mark on the rapidly expanding city. Outside the conservative, Anglican, land-owning establishment, these non-conformists were cementing their positions in society. One of the most notable was the Wilson family of Sharrow Mills, just along the road from here. They had bought more land in the valley than they needed for their business and sold some of it to help create the Botanical Gardens and the General Cemetery.

The Sheffield Botanical Gardens (7.7 hectares, 19 acres) was opened in 1836. Designed by Robert Marnock, in the Gardenesque style, the site now has fifteen different garden areas featuring collections of plants from all over the world, and impressive curvilinear glass pavilions.

Leaving by the south-east (Thompson Road) exit, we can just glimpse Sharrow Mills at the end of Snuff Mill Lane (no access), which has been producing snuff since the 1730s and is still in operation today! And perhaps most amazingly, a descendant of the founding Wilson is still running it (seven generations later).

Next, we enter the Sheffield General Cemetery (5.5 hectares, 13.6 acres) through the somewhat dilapidated Egyptian-style gatehouse which lies directly over the Porter Brook, giving the crossing of this boundary a more mythological feel.

The cemetery was also opened in 1836, in what was then countryside. The graveyards in the city centre were overflowing and there was an urgent need to find more space. The cemetery was intended to be a place where people could be buried in a way that reflected their earthly wealth and status, and it became established as the principal burial ground in Victorian Sheffield, containing 87,000 graves.

But it was also intended as a place for the living. It has sweeping vistas and inspiring architecture – the grand scheme celebrated designer Robert Marnock’s attitudes towards life. The cemetery was one of the first in Britain to promote this type of landscape, with the explicit purpose of creating an uplifting outlook, in which people could contemplate the beauty and tranquillity of their surroundings.

The Corbusier-inspired Park Hill estate, the Victorian station and the Cutting Edge water feature

‘The best thing about Sheffield music is that it’s DIY, it’s participatory, it’s democratic, anyone can put a gig on.’ PETE GREEN

The cemetery is the resting place of many important figures in Sheffield history such as Mark Firth, the steel manufacturer, and Samuel Holberry, the Chartist. It was closed for burials in 1978 and is now a local nature reserve.

We get three significant final glimpses of the brook as it becomes more culverted, modified and neglected. To the citizens of Sheffield, the Porter Brook is a hidden, forgotten stream, hard to recognise from its natural beginnings in the countryside (where we were only a couple of hours earlier), seemingly devoid of life and interest, a place that attracts rubbish and pollution. It is only really noticed when it floods occasionally.

Our last sightings: as we pass down Mary Street, just to the left of the road, with a view across a deserted car park and a derelict cutlery factory. Then going under the road in Matilda Street, and finally just alongside the car park on the south side of the station, before it finally enters a culvert.

How many people have stood on Platform 5 of the station, not realising that Sheffield’s Porter Brook joins with the flow of the River Sheaf in the darkness below, in a culvert called the Megatron. The station is elevated above the water on stone Victorian pillars, and the culvert is so large and impressive that it has featured on a list of most impressive caves in the world.

And so, our journey ends at the Cutting Edge water feature at the station entrance – the flow of which, at least in my mind, is that of the Porter Brook which passes so close by. What a totally satisfactory completion of our journey.