Café ’Ino

FOUR CEILING FANS spinning overhead.

The Café ’Ino is empty save for the Mexican cook and a kid named Zak who sets me up with my usual order of brown toast, a small dish of olive oil, and black coffee. I huddle in my corner, still wearing my coat and watch cap. It’s 9 a.m. I’m the first one here. Bedford Street as the city awakens. My table, flanked by the coffee machine and the front window, affords me a sense of privacy, where I withdraw into my own atmosphere.

The end of November. The small café feels chilly. So why are the fans turning? Maybe if I stare at them long enough my mind will turn as well.

It’s not so easy writing about nothing.

I can hear the sound of the cowpoke’s slow and authoritative drawl. I scribble his phrase on my napkin. How can a fellow get your goat in a dream and then have the grit to linger? I feel a need to contradict him, not just a quick retort but with action. I look down at my hands. I’m sure I could write endlessly about nothing. If only I had nothing to say.

After a time Zak places a fresh cup before me.

—This is the last time I’ll be serving you, he says solemnly.

He makes the best coffee around, so I am sad to hear.

—Why? Are you going somewhere?

—I’m going to open a beach café on the boardwalk in Rockaway Beach.

—A beach café! What do you know, a beach café!

I stretch my legs and watch as Zak performs his morning tasks. He could not have known that I once harbored a dream of having a café of my own. I suppose it began with reading of the café life of the Beats, surrealists, and French symbolist poets. There were no cafés where I grew up but they existed within my books and flourished in my daydreams. In 1965 I had come to New York City from South Jersey just to roam around, and nothing seemed more romantic than just to sit and write poetry in a Greenwich Village café. I finally got the courage to enter Caffè Dante on MacDougal Street. Unable to afford a meal, I just drank coffee, but no one seemed to mind. The walls were covered with printed murals of the city of Florence and scenes from The Divine Comedy. The same scenes remain to this day, discolored by decades of cigarette smoke.

In 1973 I moved into an airy whitewashed room with a small kitchen on that same street, just two short blocks from Caffè Dante. I could crawl out the front window and sit on the fire escape at night and clock the action that flowed through the Kettle of Fish, one of Jack Kerouac’s frequented bars. There was a small stall around the corner on Bleecker Street where a young Moroccan sold fresh rolls, anchovies packed in salt, and bunches of fresh mint. I would rise early and buy supplies. I’d boil water and pour it into a teapot stuffed with mint and spend the afternoons drinking tea, smoking bits of hashish, and rereading the tales of Mohammed Mrabet and Isabelle Eberhardt.

Café ’Ino didn’t exist back then. I would sit by a low window in Caffè Dante that looked out into the corner of a small alley, reading Mrabet’s The Beach Café. A young fish-seller named Driss meets a reclusive, uncongenial codger who has a so-called café with only one table and one chair on a rocky stretch of shore near Tangier. The slow-moving atmosphere surrounding the café so captivated me that I desired nothing more than to dwell within it. Like Driss, I dreamed of opening a place of my own. I thought about it so much I could almost enter it: the Café Nerval, a small haven where poets and travelers might find the simplicity of asylum.

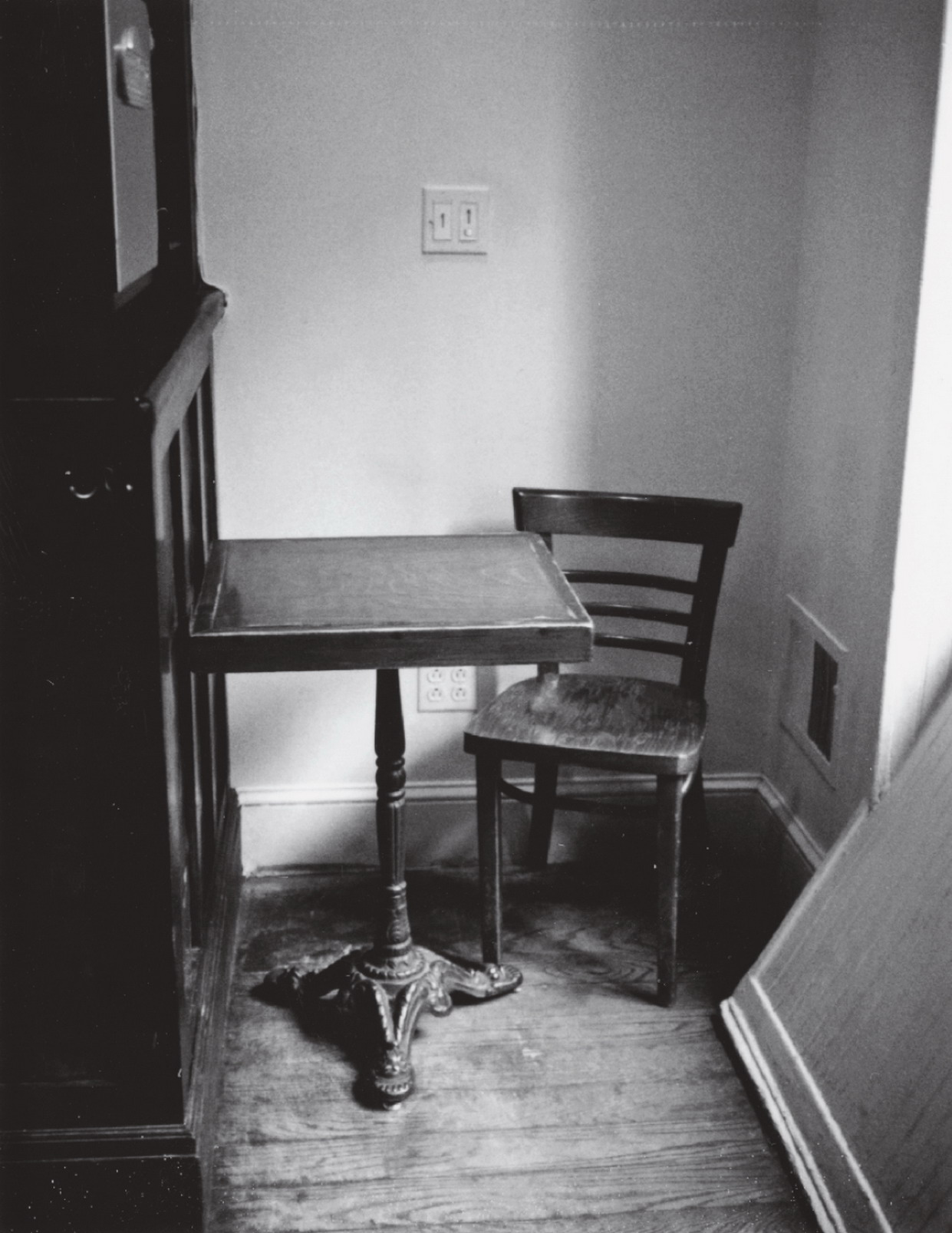

I imagined threadbare Persian rugs on wide-planked floors, two long wood tables with benches, a few smaller tables, and an oven for baking bread. Every morning I would wipe down the tables with aromatic tea like they do in Chinatown. No music no menus. Just silence black coffee olive oil fresh mint brown bread. Photographs adorning the walls: a melancholic portrait of the café’s namesake, and a smaller image of the forlorn poet Paul Verlaine in his overcoat, slumped before a glass of absinthe.

In 1978 I came into a little money and was able to pay a security deposit toward the lease of a one-story building on East Tenth Street. It had once been a beauty parlor but stood empty save for three white ceiling fans and a few folding chairs. My brother, Todd, supervised repairs and we whitewashed the walls and waxed the wood floors. Two wide skylights flooded the space with light. I spent several days sitting beneath them at a card table, drinking deli coffee and plotting my next move. I would need funds for a new toilet and a coffee machine and yards of white muslin to drape the windows. Practical things that usually receded into the music of my imagination.

In the end I was obliged to abandon my café. Two years before, I had met the musician Fred Sonic Smith in Detroit. It was an unexpected encounter that slowly altered the course of my life. My yearning for him permeated everything—my poems, my songs, my heart. We endured a parallel existence, shuttling back and forth between New York and Detroit, brief rendezvous that always ended in wrenching separations. Just as I was mapping out where to install a sink and a coffee machine, Fred implored me to come and live with him in Detroit. Nothing seemed more vital than to join my love, whom I was destined to marry. Saying good-bye to New York City and the aspirations it contained, I packed what was most precious and left all else behind—in the wake, forfeiting my deposit and my café. I didn’t mind. The solitary hours I’d spent drinking coffee at the card table, awash in the radiance of my café dream, were enough for me.

Some months before our first wedding anniversary Fred told me that if I promised to give him a child he would first take me anywhere in the world. Without hesitation I chose Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, a border town in northwest French Guiana, on the North Atlantic coast of South America. I had long wished to see the remains of the French penal colony where hard-core criminals were once shipped before being transferred to Devil’s Island. In The Thief’s Journal Jean Genet had written of Saint-Laurent as hallowed ground and of the inmates incarcerated there with devotional empathy. In his Journal he wrote of a hierarchy of inviolable criminality, a manly saintliness that flowered at its crown in the terrible reaches of French Guiana. He had ascended the ladder toward them: reform school, petty thief, and three-time loser; but as he was sentenced the prison he’d held in such reverence was closed, deemed inhumane, and the last living inmates were returned to France. Genet served his time in Fresnes Prison, bitterly lamenting that he would never attain the grandeur that he aspired to. Devastated, he wrote: I am shorn of my infamy.

Genet was imprisoned too late to join the brotherhood he had immortalized in his work. He was left outside the prison walls like the lame boy in Hamelin who was denied entrance into a child’s paradise because he arrived too late to enter its doors.

At seventy, he was reportedly in poor health and most likely would never go there himself. I envisioned bringing him its earth and stone. Though often amused by my quixotic notions, Fred did not make light of this self-imposed task. He agreed without argument. I wrote William Burroughs, whom I had known since my early twenties. Close to Genet and possessing his own romantic sensibility, William promised to assist me in delivering the stones at the proper time.

Preparing for our trip Fred and I spent our days in the Detroit Public Library studying the history of Suriname and French Guiana. We looked forward to exploring a place neither of us had been, and we mapped the first stages of our journey: the only available route was a commercial flight to Miami, then a local airline to take us through Barbados, Grenada, and Haiti, finally disembarking in Suriname. We would have to find our way to a river town outside the capital city and once there hire a boat to cross the Maroni River into French Guiana. We plotted our steps late into the night. Fred bought maps, khaki clothing, traveler’s checks, and a compass; cut his long, lank hair; and bought a French dictionary. When he embraced an idea he looked at things from every angle. He did not read Genet, however. He left that up to me.

Fred and I flew on a Sunday to Miami and stayed for two nights in a roadside motel called Mr. Tony’s. There was a small black-and-white television bolted near the low ceiling that worked by inserting quarters. We ate red beans and yellow rice in Little Havana and visited Crocodile World. The short stay readied us for the extreme heat we were about to face. Our trip was a lengthy process, as all passengers were obliged to deplane in Grenada and Haiti while the hold was searched for smuggled goods. We finally landed in Suriname at dawn; a handful of young soldiers armed with automatic weapons waited as we were herded into a bus that transported us to a vetted hotel. The first anniversary of a military coup that overthrew the democratic government on February 25, 1980, was looming: an anniversary only a few days before our own. We were the only Americans around and they assured us we were under their protection.

After we spent a few days bending in the heat of the capital city of Paramaribo, a guide drove us 150 kilometers to the town of Albina on the west bank of the river bordering French Guiana. The pink sky was veined in lightning. Our guide found a young boy who agreed to take us across the Maroni River by pirogue, a long, dugout canoe. Packed prudently, our bags were quite manageable. We pushed off in a light rain that swiftly escalated into a torrential downpour. The boy handed me an umbrella and warned us not to trail our fingers in the water surrounding the low-slung wooden boat. I suddenly noticed the river teeming with tiny black fish. Piranha! He laughed as I quickly withdrew my hand.

In an hour or so the boy dropped us off at the foot of a muddy embankment. He dragged his pirogue onto land and joined some workers taking cover beneath a length of black oilcloth stretched over four wooden posts. They seemed amused by our momentary confusion and pointed us in the direction of the main road. As we struggled up a slippery knoll, the calypso beat of Mighty Swallow’s “Soca Dance” wafting from a boom box was all but drowned by the insistent rain. Completely drenched we tramped through the empty town, finally taking cover in what seemed to be the only existing bar. The bartender served me coffee and Fred had a beer. Two men were drinking calvados. The afternoon slipped by as I consumed several cups of coffee while Fred engaged in a broken French-English conversation with a leathery-skinned fellow who presided over the nearby turtle reserves. As the rains subsided, the owner of the local hotel appeared offering his services. Then a younger, sulkier version emerged to take our bags, and we followed them along a muddied trail down a hill to our new lodgings. We had not even booked a hotel and yet a room awaited us.

The Hôtel Galibi was spartan yet comfortable. A small bottle of watered-down cognac and two plastic cups were set on the dresser. Spent, we slept, even as the returning rain beat relentlessly upon the corrugated tin roof. There were bowls of coffee waiting for us when we awoke. The morning sun was strong. I left our clothes to dry on the patio. There was a small chameleon melting into the khaki color of Fred’s shirt. I spread the contents of our pockets on a small table. A wilting map, damp receipts, dismembered fruits, Fred’s ever-present guitar picks.

Around noon a cement worker drove us outside the ruins of the Saint-Laurent prison. There were a few stray chickens scratching in the dirt and an overturned bicycle, but no one seemed to be around. Our driver entered with us through a low stone archway and then just slipped away. The compound had the air of a tragically defunct boomtown—one that had mined the souls and shipped their husks to Devil’s Island. Fred and I moved about in alchemical silence, mindful not to disturb the reigning spirits.

In search of the right stones I entered the solitary cells, examining the faded graffiti tattooing the walls. Hairy balls, cocks with wings, the prime organ of Genet’s angels. Not here, I thought, not yet. I looked around for Fred. He had maneuvered through the high grasses and overgrown palms, finding a small graveyard. I saw him paused before a headstone that read Son your mother is praying for you. He stood there for a long time looking up at the sky. I left him alone and inspected the outbuildings, finally choosing the earthen floor of the mass cell to gather the stones. It was a dank place the size of a small airplane hangar. Heavy, rusted chains were anchored into the walls illuminated by slim shafts of light. Yet there was still some scent of life: manure, earth, and an array of scuttling beetles.

I dug a few inches seeking stones that might have been pressed by the hard-calloused feet of the inmates or the soles of heavy boots worn by the guards. I carefully chose three and put them in an oversized Gitanes matchbox, leaving the bits of earth clinging to them intact. Fred offered his handkerchief to wipe the dirt from my hands, and then shaking it out he made a little sack for the matchbox. He placed it in my hands, the first step toward placing them in the hands of Genet.

We didn’t stay long in Saint-Laurent. We went seaside but the turtle reserves were off-limits, as they were spawning. Fred spent a lot of time in the bar, talking to the fellows. Despite the heat, Fred wore a shirt and a tie. The men seemed to respect him, regarding him without irony. He had that effect on other men. I was content just sitting on a crate outside the bar staring down an empty street I had never seen and might never see again. Prisoners once were paraded on this same stretch. I closed my eyes, imagining them dragging their chains in the intense heat, cruel entertainment for the few inhabitants of a dusty, forsaken town.

As I walked from the bar to the hotel I saw no dogs or children at play and no women. For the most part I kept to myself. Occasionally I caught glimpses of the maid, a barefoot girl with long, dark hair, scurrying about the hotel. She smiled and gestured but spoke no English, always in motion. She tidied our room and took our clothes from the patio, then washed and pressed them. In gratitude I gave her one of my bracelets, a gold chain with a four-leaf clover, which I spotted dangling from her wrist as we departed.

There were no trains in French Guiana, no rail service at all. The fellow from the bar had found us a driver, who carried himself like an extra in The Harder They Come. He wore aviator sunglasses, cocked cap, and a leopard-print shirt. We arranged a price and he agreed to drive us the 268 kilometers to Cayenne. He drove a beat-up tan Peugeot and insisted our bags stay with him in the front seat as chickens were normally transported in the trunk. We drove along Route Nationale through the continuing rains interrupted by fleeting sun, listening to reggae songs on a station riddled with static. When the signal was lost the driver switched to a cassette by a band called Queen Cement.

Every once in a while I untied the handkerchief to look at the Gitanes matchbox with its silhouette of a Gypsy posturing with her tambourine in a swirl of indigo-tinged smoke. But I did not open it. I pictured a small yet triumphal moment passing the stones to Genet. Fred held my hand as we wordlessly wound through dense forests, and passed short, sturdy Amerindians with broad shoulders, balancing iguanas squarely on their heads. We traveled through tiny communes like Tonate that had just a few houses and one six-foot crucifix. We asked the driver to stop. He got out and examined his tires. Fred took a photograph of the sign that read Tonate. Population 9, and I said a little prayer.

We were unfettered by any particular desire or expectation. The primary mission accomplished, we had no ultimate destination, no hotel reservations; we were free. But as we approached Kourou we sensed a shift. We were entering a military zone and hit a checkpoint. The driver’s identity card was inspected and after an interminable stretch of silence we were ordered to get out of the car. Two officers searched the front and back seats, finding a switchblade with a broken spring in the glove box. That can’t be so bad, I thought, but as they knocked on the back of the trunk our driver became markedly agitated. Dead chickens? Maybe drugs. They circled around the car, and then asked him for the keys. He threw them in a shallow ravine and bolted but was swiftly wrestled to the ground. I glanced sidelong at Fred. He’d had trouble with the law as a young man and had always been wary of authority. He betrayed no emotion and I followed his lead.

They opened the trunk of the car. Inside was a man who looked to be in his early thirties curled up like a slug in a rusting conch shell. He seemed terrified as they poked him with a rifle and ordered him to get out. We were all herded to the police headquarters, put in separate rooms, and interrogated in French. I knew enough to answer their simplest questions, and Fred, installed in another room, conversed in bits of barroom French. Suddenly the commander arrived and we were brought before him. He was barrel-chested with dark, sad eyes and a thick mustache that dominated his careworn face browned by sun. Fred quickly took stock of things. I slipped into the role of compliant female, for in this obscure annex of the Foreign Legion it was definitely a man’s world. I watched silently as the human contraband, stripped and shackled, was led away. Fred was ordered into the commander’s office. He turned and looked at me. Stay calm was the message telegraphed from his pale blue eyes.

An officer brought in our bags, and another wearing white gloves went through everything. I sat there holding the handkerchief sack. I was relieved I was not asked to surrender it, for as an object it had already manifested a sacredness second only to my wedding ring. I sensed no danger but counseled myself to hold my tongue. An interrogator brought me a black coffee on an oval tray with an inlay of a blue butterfly and entered the commander’s office. I could see Fred’s profile. After a time they all came out. They seemed in amiable spirits. The commander gave Fred a manly embrace and we were placed in a private car. Neither of us said a word as we pulled into the capital city of Cayenne, situated on the banks of the estuary of the Cayenne River. Fred had the address of a hotel given to him by the commander. We were dropped off at the foot of a hill, the end of the line. It’s somewhere up there, he motioned, and we carried our bags up the stone steps that led to the path to our next dwelling place.

—What did you two talk about? I asked.

—I really can’t say for sure, he only spoke French.

—How did you communicate?

—Cognac.

Fred seemed deep in thought.

—I know that you are concerned about the fate of the driver, he said, but it’s out of our hands. He placed us in real jeopardy and in the end my concern was for you.

—Oh, I wasn’t afraid.

—Yes, he said, that’s why I was concerned.

The hotel was to our liking. We drank French brandy from a paper sack and slept wrapped in layers of mosquito netting. There was no glass in the windows—neither in our hotel nor in the houses below. No air conditioners, just the wind and sporadic rain providing relief from the heat and dust. We listened to the Coltrane-like cries of simultaneous saxophones wafting from the cement tenements. In the morning we explored Cayenne. The town square was more of a trapezoid, tiled black-and-white and framed with high palms. It was Carnival time, unbeknownst to us, and the city was all but deserted. The city hall, a nineteenth-century whitewashed French colonial, was closed for the holiday. We were drawn to a seemingly abandoned church. When we opened the gate, rust came off on our hands. We dropped coins into an old Chock Full O’ Nuts can with the slogan The Heavenly Coffee placed at the entrance for donations. Dust mites dispersed in beams of light then formed a halo above an angel of glowing alabaster; icons of saints were trapped behind fallen debris, rendered unrecognizable under layers of dark lacquer.

All things seemed to flow in slow motion. Although strangers we moved about unnoticed. Men haggled over a price for a live iguana with a long, slapping tail. Overcrowded ferries departed for Devil’s Island. Calypso music poured from a mammoth disco in the shape of an armadillo. There were a few small souvenir stands with identical fare: thin, red blankets made in China and metallic blue raincoats. But mostly there were lighters, all kinds of lighters, with images of parrots, spaceships, and men of the Foreign Legion. There was nothing much to keep one there and we thought of applying for a visa to Brazil, having our pictures taken by a mysterious Chinaman called Dr. Lam. His studio was filled with large-format cameras, broken tripods, and rows of herbal remedies in large glass vials. We picked up our visa pictures yet we stayed in Cayenne until our anniversary as if bewitched.

On the last Sunday of our journey, women in bright dresses and men in top hats were celebrating the end of Carnival. Following their makeshift parade on foot, we ended up at Rémire-Montjoly, a commune southeast of the city. The revelers dispersed. Rémire was fairly uninhabited and Fred and I stood mesmerized by the emptiness of the long, sweeping beaches. It was a perfect day for our anniversary and I couldn’t help thinking it was the perfect spot for a beach café. Fred went on before me, whistling to a black dog somewhat up ahead. There was no sign of his master. Fred threw a stick into the water and the dog fetched it. I knelt down in the sand and sketched out plans for an imaginary café with my finger.

An unwinding spool of obscure angles, a glass of tea, an opened journal, and a round metal table balanced with an empty matchbook. Cafés. Le Rouquet in Paris, Café Josephinum in Vienna, Bluebird Coffeeshop in Amsterdam, Ice Café in Sydney, Café Aquí in Tucson, Wow Café at Point Loma, Caffe Trieste in North Beach, Caffè del Professore in Naples, Café Uroxen in Uppsala, Lula Cafe in Logan Square, Lion Cafe in Shibuya, and Café Zoo in the Berlin train station.

The café I’ll never realize, the cafés I’ll never know. As if reading my mind, Zak wordlessly brings me a fresh cup.

—When will your café open? I ask him.

—When the weather changes, hopefully early spring. A couple of buddies and me. We have to get some things together, and we need a little more capital to buy some equipment.

I ask him how much, offer to invest.

—Are you sure, he asks, somewhat surprised, for in truth we don’t know each other very well, complicit solely through our daily coffee ritual.

—Yeah, I’m sure. I once thought about having a café of my own.

—You’ll have free coffee for the rest of your life.

— God willing, I say.

I sit before Zak’s peerless coffee. Overhead the fans spin, feigning the four directions of a traversing weather vane. High winds, cold rain, or the threat of rain; a looming continuum of calamitous skies that subtly permeate my entire being. Without noticing, I slip into a light yet lingering malaise. Not a depression, more like a fascination for melancholia, which I turn in my hand as if it were a small planet, streaked in shadow, impossibly blue.