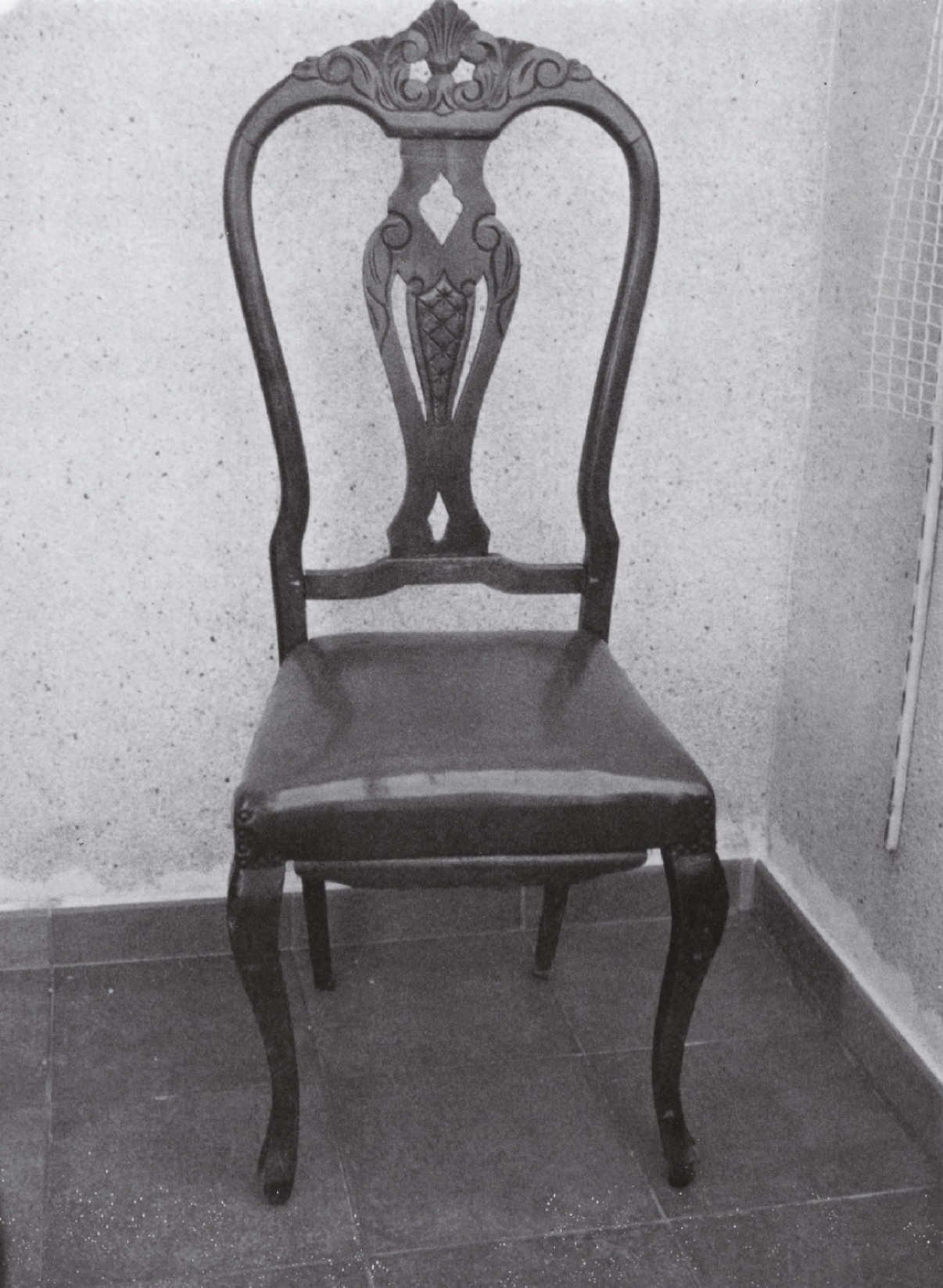

Roberto Bolaño’s chair, Blanes, Spain

Changing Channels

I CLIMB THE STAIRS to my room with its lone skylight, a worktable, a bed, my brother’s Navy flag, bundled and tied by his own hand, and a small armchair draped in threadbare linen set back in the corner by the window. I shed my coat, time to get on with it. I have a fine desk but I prefer to work from my bed, as if I’m a convalescent in a Robert Louis Stevenson poem. An optimistic zombie propped by pillows, producing pages of somnambulistic fruit—not quite ripe or overripe. Occasionally I write directly into my small laptop, sheepishly glancing over to the shelf where my typewriter with its antiquated ribbon sits next to an obsolete Brother word processor. A nagging allegiance prevents me from scrapping either of them. Then there are the scores of notebooks, their contents calling—confession, revelation, endless variations of the same paragraph—and piles of napkins scrawled with incomprehensible rants. Dried-out ink bottles, encrusted nibs, cartridges for pens long gone, mechanical pencils emptied of lead. Writer’s debris.

I skip Thanksgiving, dragging my malaise through December, with a prolonged period of enforced solitude, though sadly without crystalline effect. In the mornings I feed the cats, mutely gather my things, and then make my way across Sixth Avenue to Café ’Ino, sitting at my usual table in the corner drinking coffee, pretending to write, or writing in earnest, with more or less the same questionable results. I avoid social commitments and aggressively arrange to spend the holidays alone. On Christmas Eve I present the cats with catnip-enhanced mice toys and exit aimlessly into the vacant night, finally landing near the Chelsea Hotel at a movie theater offering a late showing of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. I buy my ticket and a large black coffee and a bag of organic popcorn at the corner deli, and then settle in my seat in the back of the theater. Just me and a score of slackers, comfortably isolated from the world, attaining our own brand of holiday well-being, no gifts, no Christ child, no tinsel or mistletoe, only a sense of complete freedom. I liked the looks of the movie. I had already seen the Swedish version without subtitles but hadn’t read the books, so now I would be able to piece together the plot and lose myself in the bleak Swedish landscape.

It was after midnight when I walked home. It was a relatively mild night and I felt an overriding sense of calm that slowly bled into a desire to be home in my own bed. There were few signs of Christmas on my empty street, just some stray tinsel embedded in the wet leaves. I said goodnight to the cats stretched out on the couch, and as I headed upstairs to my room, Cairo, an Abyssinian runt with a coat the color of the pyramids, followed at my heels. There I unlocked a glass cabinet and carefully unwrapped a Flemish crèche consisting of Mary and Joseph, two oxen, and a babe in his cradle, and arranged them on the top of my bookcase. Carved from bone, they had developed a golden patina through two centuries of age. How sad, I thought, admiring the oxen, that they are only displayed at Christmastide. I wished the babe a happy birthday and removed the books and papers from my bed, brushed my teeth, turned down the coverlet, and let Cairo sleep on my stomach.

New Year’s Eve was pretty much the same story with no particular resolution. As thousands of drunken revelers disbursed in Times Square, my little Abyssinian circled the floor with me as I paced, wrestling with a poem I was aiming to finish to usher in the New Year, in homage to the great Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño. In reading his Amulet I noted a passing reference to the hecatomb—an ancient ritualistic slaughter of one hundred oxen. I decided to write a hecatomb for him—a hundred-line poem. It was to be a way to thank him for spending the last stretch of his brief life racing to finish his masterpiece, 2666. If only he could have been given special dispensation, been allowed to live. For 2666 seemed set up to go on forever, as long as he wished to write. Such a sad portion of injustice served to beautiful Bolaño, to die at the height of his powers at fifty years old. The loss of him and his unwritten denying us at least one secret of the world.

As the last hours of the year ticked away I wrote and rewrote then recited the lines aloud. But as the ball dropped in Times Square I realized I had written 101 lines by mistake and couldn’t face figuring which one to sacrifice. It also occurred to me that I was inadvertently invoking the slaughter of the kin of the glowing bone oxen watching over the Christ child in the crèche on my bookcase. Did it matter the ritual was in word only? Did it matter my oxen were carved in bone? After a few minutes of looping rumination I temporarily laid aside my hecatomb and switched over to a movie. While watching The Gospel According to Saint Matthew, I noticed that Pasolini’s young Mary resembled the equally young Kristen Stewart. I placed it on pause and made a cup of Nescafé, slipped on a hoodie, and went outside and sat on my stoop. It was a cold, clear night. A few drunken kids, probably from New Jersey, called out to me.

—What the fuck time is it?

—Time to puke, I answered.

—Don’t say that around her, she’s been doing it all night.

She was a barefoot redhead wearing a sequined minidress.

—Where’s her coat? Should I get her a sweater?

—She’s all right.

—Well, happy New Year.

—Did it happen yet?

—Yeah, about forty-eight minutes ago.

They hastily disappeared around the corner, leaving a deflating silver balloon hovering above the sidewalk. I walked over to rescue it just as it limply touched ground.

—That about sums it up, I said aloud.

Snow. Just enough snow to scrape off my boots. Donning my black coat and watch cap, I trudge across Sixth Avenue like a faithful postman, delivering myself daily before the orange awning of Café ’Ino. As I labor yet again on variations of the hecatomb poem for Bolaño, my morning sojourn lengthens well into the afternoon. I order Tuscan bean soup, brown bread with olive oil, and more black coffee. I count the lines of the envisioned one-hundred-line poem, now three lines shy. Ninety-seven clues but nothing solved, another cold-case poem.

I should get out of here, I am thinking, out of the city. But where would I go that I would not drag my seemingly incurable lethargy along with me, like the worn canvas sack of an angst-driven teenage hockey player? And what would become of my mornings in my little corner and my late nights scanning the TV channels with an obstinate channel changer that needed to be tapped several times into awareness?

—I changed your batteries, I say pleadingly, so change the damn channel.

—Aren’t you supposed to be working?

—I’m watching my crime shows, I murmur unapologetically, not a trifling thing. Yesterday’s poets are today’s detectives. They spend a life sniffing out the hundredth line, wrapping up a case, and limping exhausted into the sunset. They entertain and sustain me. Linden and Holder. Goren and Eames. Horatio Caine. I walk with them, adopt their ways, suffer their failures, and consider their movements long after an episode ends, whether in real time or rerun.

The haughtiness of a small handheld device! Perhaps I should be concerned as to why I have conversations with inanimate objects. But as it has been part of my waking life since I was a child I have no problem with that. What really bothers me is why I have spring fever in January. Why the coils of my brain seem dusted with a vortex of pollens. Sighing, I meander around my room scanning for cherished things to make certain they haven’t been drawn into that half-dimensional place where things just disappear. Things beyond socks or glasses: Kevin Shields’s EBow, a snapshot of a sleepy-faced Fred, a Burmese offering bowl, Margot Fonteyn’s ballet slippers, a misshapen clay giraffe formed by my daughter’s hands. I pause before my father’s chair.

My father sat at his desk, in this chair, for decades, writing checks, filling out tax forms, and working fervently on his own system for handicapping horses. Bundles of The Morning Telegraph were stacked against the wall. A journal wrapped in jeweler’s cloth, noting wins and losses from imaginary bets, kept in the left-hand drawer. No one dared touch it. He never spoke about his system but he labored over it religiously. He was neither a betting man nor had the resources to bet. He was a factory man with a mathematical curiosity, handicapping heaven, searching for patterns, and a portal of probability opening up onto the meaning of life.

I admired my father from a distance. He seemed dreamily estranged from our domestic life. He was kind and open-minded, having an inner elegance that set him apart from our neighbors. Yet he never placed himself above them. He was a decent man who did his job. A runner when young, a superb athlete and acrobat. In World War II he was stationed in the jungles of New Guinea and the Philippines. Though he opposed violence he was a patriotic soldier, but the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki broke his heart and he mourned the cruelty and weakness of our material society.

My father worked the night shift. He slept in the day and left while we were at school and returned late at night when we were sleeping. On the weekends we were obliged to give him some privacy as he had little time for himself. He would sit in his favorite chair watching baseball with the family Bible on his lap. He often read passages aloud attempting to provoke discussion. Question everything, he would tell us. Through the seasons he dressed in a black sweatshirt, worn dark pants rolled up to his calves, and moccasins. He was never without moccasins, as my sister, my brother, and I would save our coins throughout the year to buy him a new pair every Christmas. In his last years he fed the birds so consistently, in all manner of weather, that they came to him when he called, alighting upon his shoulders.

When he died I inherited his desk and chair. Inside the desk was a cigar box containing canceled checks, nail clippers, a broken Timex watch, and a yellowed newspaper cutting of my beaming self in 1959, being awarded third prize in a national safety-poster contest. I still keep the box in the top right-hand drawer. His sturdy wooden chair that my mother irreverently decorated with decals of burnished roses is against the wall facing my bed. A cigarette burn scarring the seat gives the chair a feel of life. I run my finger over the burn, conjuring his soft pack of Camel straights. The same brand John Wayne smoked, with the golden dromedary and palm tree silhouette on the pack, evoking exotic places and the French Foreign Legion.

You should sit on me, his chair urges, but I can’t bring myself to do it. We were never allowed to sit at my father’s desk, so I don’t use his chair, just keep it near. I did once sit in the chair of Roberto Bolaño when visiting his family’s home in the seacoast town of Blanes, in northeast Spain. I immediately regretted it. I had taken four pictures of it, a simple chair that he superstitiously carried with him from one dwelling place to another. It was his writing chair. Did I think that sitting in it would make me a better writer? With a shiver of self-admonishment, I wipe dust from the glass protecting my Polaroid of that same chair.

I go downstairs, then carry two full boxes back to my room and dump the contents onto my bed. Time to face up to the last mail of the year. First I sift through brochures for such things like time-sharing condos in Jupiter Beach, unique and lucrative methods of senior-citizen investing, and full-color illustrated packets on how to cash in my frequent-flier miles for exciting gifts. All left unopened for the recycle bin yet producing a pang of guilt, considering the amount of trees necessary to churn out this mound of unsolicited crap. On the other hand there are some good catalogues offering nineteenth-century German manuscripts, memorabilia of the Beat generation, and rolls of vintage Belgium linen to stack by the toilet for future diversion. I saunter past my coffeemaker that sits like a huddled monk on a small metal cabinet storing my porcelain cups. Patting its head, avoiding eye contact with the typewriter and channel changer, I reflect on how some inanimate objects are so much nicer than others.

Clouds move past the sun. A milky light pervades the skylight and spreads into my room. I have a vague sense of being summoned. Something is calling to me, so I stay very still, like Detective Sarah Linden, in the opening credits of The Killing, on the edge of a marsh at twilight. I slowly advance toward my desk and lift the top. I don’t open it very often, as some precious things hold memories too painful to revisit. Thankfully I need not look inside, as my hand knows the size, texture, and location of each object it contains. Reaching beneath my one childhood dress, I remove a small metal box with tiny perforated holes in the cover. I take a deep breath before I open it, as I harbor the irrational fear that the sacred contents may dissipate when confronted with a sudden onrush of air. But no, everything is intact. Four small hooks, three feathered fishing lures, and another composed of soft purple transparent rubber, like a Juicy Fruit or a Swedish Fish, shaped like a comma with a spiraled tail.

—Hello, Curly, I whisper, and am instantly gladdened.

I lightly tap him with my fingertip. I feel the warmth of recognition, memories of time spent fishing with Fred in a rowboat on Lake Ann in northern Michigan. Fred taught me to cast and gave me a portable Shakespeare rod whose parts fit like arrows in a carrying case shaped like a quiver. Fred was a graceful and patient caster with an arsenal of lures, bait, and weights. I had my archer rod and this same little box holding Curly—my secret ally. My little lure! How could I have forgotten our hours of sweet divination? How well he served me when cast into unfathomable waters, performing his persuasive tango with slippery bass that I later scaled and panfried for Fred.

The king is dead, no fishing today.

Gently placing Curly back in my desk, I tackle my mail with new resolve—bills, petitions, invitations for gala events past, imminent jury duty. Then I swiftly set aside one item of particular interest—a plain brown envelope stamped and sealed with wax with the raised letters CDC. I hurry to a locked cabinet, choosing a slim bone-handled letter opener, the only proper way to open a precious piece of correspondence from the Continental Drift Club. The envelope contains a small red card with the number twenty-three stenciled in black and a handwritten invitation to deliver a talk of my choosing at the semi-annual convention to take place in mid-January in Berlin.

I experience a wealth of excitement, but I have no time to lose, as the letter is dated some weeks ago. I hastily write a response in the affirmative, then rummage through my desk for a sheet of stamps, grab my cap and coat, and drop the letter into the mailbox. Then I cross over Sixth Avenue to ’Ino. It is late afternoon and the café is empty. At my table I attempt to write a list of items to take on my journey but am immersed in a particular reverie taking me back through a handful of years through the cities of Bremen, Reykjavík, Jena, and soon Berlin, to meet again with the brethren of the Continental Drift Club.

Formed in the early 1980s by a Danish meteorologist, the CDC is an obscure society serving as an independent branch of the earth-science community. Twenty-seven members, scattered across the hemispheres, have pledged their dedication to the perpetuation of remembrance, specifically in regard to Alfred Wegener, who pioneered the theory of continental drift. The bylaws require discretion, attendance at the biannual conferences, a certain amount of applicable fieldwork, and a reasonable passion for the club’s reading list. All are expected to keep abreast of the activities of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, in the city of Bremerhaven in Lower Saxony.

I was granted membership into the CDC quite by accident. On the whole, members are primarily mathematicians, geologists, and theologians and are identified not by name but by a given number. I had written several letters to the Alfred Wegener Institute searching for a living heir in hopes of obtaining permission to photograph the great explorer’s boots. One of my letters was forwarded to the secretary of the Continental Drift Club, and after a flurry of correspondence I was invited to attend their 2005 conference in Bremen, which coincided with the 125th anniversary of the great geoscientist’s birth and thus the seventy-fifth of his death. I attended their panel discussions, a special screening at City 46 of Research and Adventure on the Ice, a documentary series containing rare footage of Wegener’s 1929 and 1930 expeditions, and joined them for a private tour of the AWI facilities in nearby Bremerhaven. I am certain I didn’t quite meet their criteria, but I suspect that after some deliberation they welcomed me due to my abundance of romantic enthusiasm. I became an official member in 2006, and was given the number twenty-three.

In 2007 we convened in Reykjavík, the largest city in Iceland. There was tremendous excitement, as that year certain members had planned to continue to Greenland for a CDC spinoff expedition. They formed a search party hoping to locate the cross that was placed in Wegener’s memory in 1931 by his brother, Kurt. It had been constructed with iron rods some twenty feet high, marking his resting place, approximately 120 miles from the western edge of the Eismitte encampment where his companions last saw him. At the time its whereabouts were unknown. I wished I could go, as I knew the great cross, were it found, would inspire a remarkable photograph, but I hadn’t the constitution required for such an endeavor. Yet I did stay on in Iceland, as Number Eighteen, a thoroughly robust Icelandic Grandmaster, surprised me by asking me to preside in his stead over a highly anticipated local chess match. My doing so would enable him to join the search party into the Greenland interior. In exchange I was promised three nights in the Hótel Borg and permission to photograph the table used in the 1972 chess match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky, currently languishing in the basement of a local government facility. I was a bit wary about the idea of monitoring the match, seeing as my love of chess was purely aesthetic. But the opportunity to photograph the holy grail of modern chess was consolation enough for staying behind.

The following afternoon I arrived with my Polaroid camera just as the table was unceremoniously delivered to the tournament hall. It was quite modest in appearance but had been signed by the two great chess players. As it turned out my duties were actually quite light; it was a junior tournament and I was merely a figurehead. The winner of the match was a thirteen-year-old girl with golden hair. Our group was photographed, after which I was given fifteen minutes to shoot the table, unfortunately bathed in fluorescent light, anything but photogenic. Our picture fared much better and graced the cover of the morning newspaper, the famed table in the foreground. After breakfast I went to the countryside with an old friend and we rode sturdy Icelandic ponies. His was white and mine was black, like two knights on a chessboard.

When I returned I received a call from a man identifying himself as Bobby Fischer’s bodyguard. He had been charged with arranging a midnight meeting between Mr. Fischer and myself in the closed dining room of the Hótel Borg. I was to bring my bodyguard, and would not be permitted to bring up the subject of chess. I consented to the meeting and then crossed the square to the Club NASA where I recruited their head technician, a trustworthy fellow called Skills, to stand as my so-called bodyguard.

Bobby Fischer arrived at midnight in a dark hooded parka. Skills also wore a hooded parka. Bobby’s bodyguard towered over us all. He waited with Skills outside the dining room. Bobby chose a corner table and we sat face-to-face. He began testing me immediately by issuing a string of obscene and racially repellent references that morphed into paranoiac conspiracy rants.

—Look, you’re wasting your time, I said. I can be just as repellent as you, only about different subjects.

He sat staring at me in silence, when finally he dropped his hood.

—Do you know any Buddy Holly songs? he asked.

For the next few hours we sat there singing songs. Sometimes separately, often together, remembering about half the lyrics. At one point he attempted a chorus of “Big Girls Don’t Cry” in falsetto and his bodyguard burst in excitedly.

—Is everything all right, sir?

—Yes, Bobby said.

—I thought I heard something strange.

—I was singing.

—Singing?

—Yes, singing.

And that was my meeting with Bobby Fischer, one of the greatest chess players of the twentieth century. He drew up his hood and left just before first light. I remained until the servers arrived to prepare the breakfast buffet. As I sat across from his chair I envisioned members of the Continental Drift Club still sleeping in their beds, or unable to sleep, filled with emotional expectation. In a few hours they would rise and embark into the icy Greenland interior in search of memory in the form of the great cross. It occurred to me, as the heavy curtains were opened and the morning light flooded the small dining area, that without a doubt we sometimes eclipse our own dreams with reality.