Bison, Zoologischer Garten, Berlin

Animal Crackers

I WAS LATE getting to Café ’Ino. My table in the corner was taken and a petulant possessiveness provoked me to go into the bathroom and wait it out. The bathroom was narrow and candlelit with a few fresh flowers in a small vase resting atop the toilet tank. Like a tiny Mexican chapel, one that you could piss in without feeling blasphemous. I left the door unlocked in case someone was in genuine need, waited for about ten minutes, and exited just as my table was freed. I wiped off the surface and ordered black coffee, brown toast, and olive oil. I wrote some notes on paper napkins for my forthcoming talk, then sat daydreaming about the angels in Wings of Desire. How wonderful it would be to meet an angel, I mused, but then I immediately realized I already had. Not an archangel like Saint Michael, but my human angel from Detroit, wearing an overcoat and no hat, with lank brown hair and eyes the color of water.

My travel to Germany was uneventful save that a security agent at the Newark Liberty Airport did not recognize my 1967 Polaroid as a camera and several minutes were wasted swiping it for explosive traces and sniffing the mute air within its bellows. A generic female voice repeated the same monotone instructions throughout the airport. Report suspicious behavior. Report suspicious behavior. As I approached the gate another woman’s voice superimposed over hers.

—We are a nation of spies, she cried, all spying on one another. We used to help one another! We used to be kind!

She was carrying a faded tapestry duffel bag. She had a dusty appearance, as if she had emerged from the bowels of a foundry. When she set down her bag and walked away, passersby seemed visibly disturbed.

On the plane I watched consecutive episodes of the Danish crime drama Forbrydelsen, the blueprint for the American series The Killing. Detective Sarah Lund is the Danish prototype of Detective Sarah Linden. Both are singular women, both wear Fair Isle ski sweaters. Lund’s are formfitting. Linden’s are dumpy, but she wears hers as a moral vest. Lund is driven by ambition. Linden’s obsessional nature is kin to her humanity. I feel her devotion to each terrible mission, the complexity of her vows, her need for solitary runs through the high grass of marshy fields. I sleepily track Lund in subtitle but my subconscious mind seeks out Linden, for even as a character in a television series she is dearer to me than most people. I wait for her every week, quietly fearing the day when The Killing will come to a finish and I will never see her again.

I follow Sarah Lund yet dream of Sarah Linden. I awake as Forbrydelsen abruptly ends and stare blankly at the screen of my personal player before passing unconscious into an incident room where a stream of briefings stakeouts and strange arcs empty into the rude smoke of isolation.

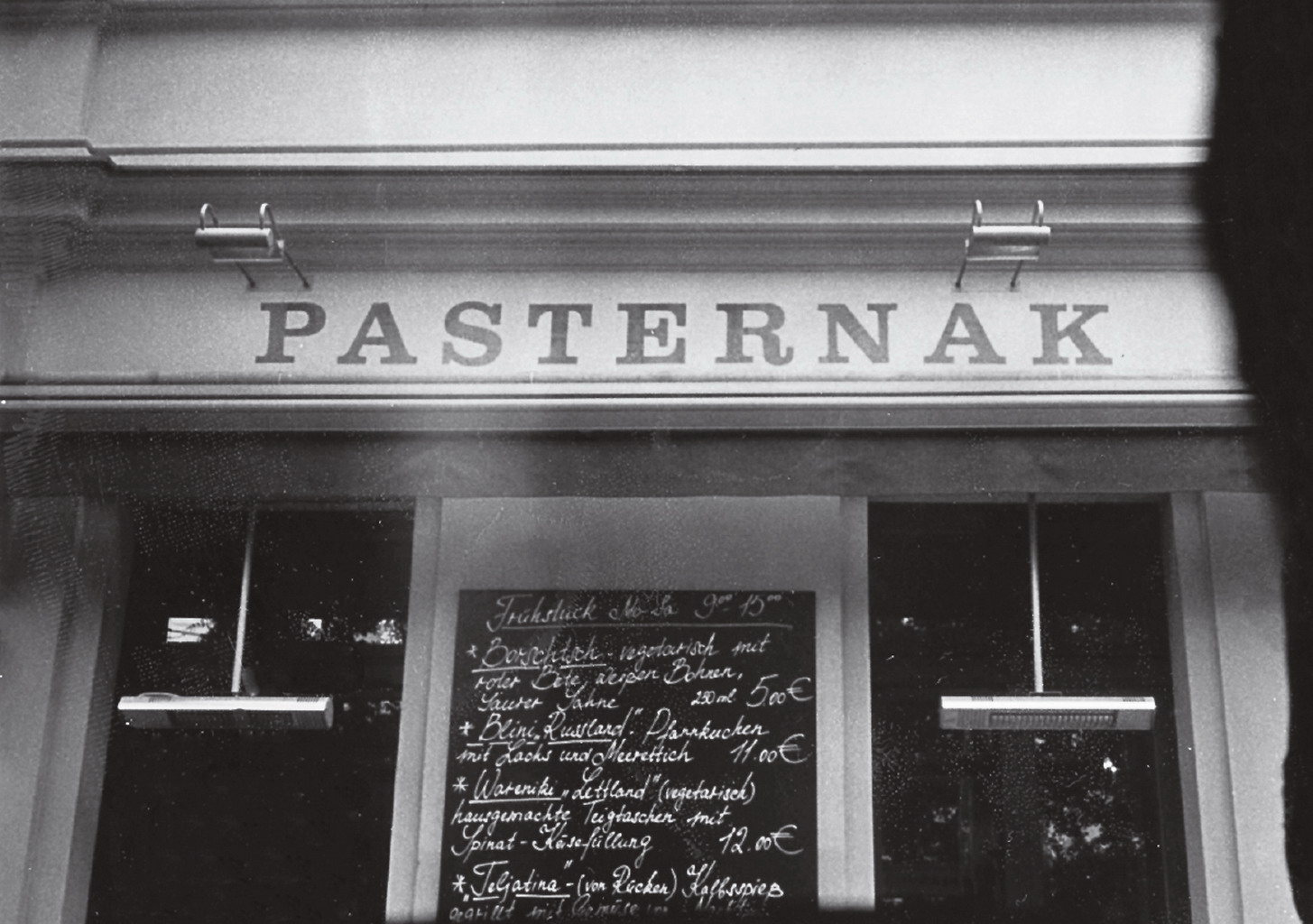

MY BERLIN HOTEL was in a renovated Bauhaus structure in the Mitte district of the former East Berlin. It had everything I needed and was in close proximity to the Pasternak café, which I discovered on a walk during a previous visit, at the height of an obsession with Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I dropped my bags in my room and went directly to the café. The proprietress greeted me warmly and I sat at my same table beneath a photograph of Bulgakov. As before, I was taken by the Pasternak’s old-world charm. The faded blue walls were dressed in photographs of the beloved Russian poets Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Mayakovsky. On the wide windowsill to my right sat an old Russian typewriter with its round Cyrillic keys, a perfect mate for my lonely Remington. I ordered the Happy Tsar—black sturgeon caviar served with a small shot of vodka and a glass of black coffee. Contented, I sat for quite a while mapping my talk on paper napkins, and then strolled the small park with the city’s oldest water tower rising from its center.

On the morning of my lecture I rose early and had coffee, watermelon juice, and brown toast in my room. I hadn’t wholly mapped out my talk, leaving a section open for improvisation and the whims of fate. I crossed the wide thoroughfare to the left of the hotel and passed through an ivy-covered gate, hoping to meditate on the coming event in the small church of St. Marien and St. Nikolai. The church was locked, but I found a secluded enclave with a statue of a boy reaching for a rose at the foot of the Madonna. Both possessed an enviable expressiveness, their marble skin worn by time and weather. I took several photographs of the boy and then returned to my room, curling up in a dark velvet armchair, drifting into a small patch of dreamless sleep.

At six I was spirited to a small lecture hall in a nearby location, like Holly Martins in The Third Man. There was nothing to distinguish our postwar meeting hall from others scattered around the former East Berlin. All twenty-seven CDC members were in attendance and the room vibrated with an air of expectancy. The proceedings opened with our theme song, a light, melancholic melody played on accordion by its composer, Number Seven, a gravedigger from the Umbrian town of Gubbio, where Saint Francis tamed the wolves. Number Seven was neither scholar nor trained musician but had the enviable distinction of being a distant relative of one of Wegener’s original team.

Our moderator delivered his opening remarks, quoting from Friedrich Schiller’s The Favor of the Moment: Once more, then, we meet / In the circles of yore.

He spoke at length concerning issues under current watch by the Alfred Wegener Institute, particularly the troubling decline of the breadth of the arctic ice sheets. After a while I felt my mind wandering and enviously glanced sidelong at my fellow members, most of whom appeared positively riveted. As he droned on I predictably drifted, weaving a tragic tale: a girl in a sealskin coat watches helplessly as the surface of the ice cracks and cruelly separates her from her Prince Charming. She falls to her knees as he floats away. The compromised ice sheet tilts and he sinks into the Arctic Sea on the back of his faltering white Icelandic pony.

Our secretary presented the minutes of our last gathering in Jena, then cheerily announced the forthcoming AWI species of the month: Sargassum muticum—a brown Japanese seaweed distinguished by the way it drifts with the ocean currents. She also noted that our request to partner with the AWI and develop their species of the month into a full-color calendar was denied, which elicited a collective groan from the calendar enthusiasts. Next we were treated with a brief slide show of Number Nine’s color landscape photography of the sites last visited by the CDC in eastern Germany, which sparked a proposal of using such images for a whole different calendar. I noticed my palms were sweating and without thinking wiped them dry with my napkin notes.

Finally, after a meandering introduction, I was invited to the podium. My talk was unfortunately introduced as The Lost Moments of Alfred Wegener. I explained that the title was actually the last, not the lost, moments, which led to a flurry of semantic bloodletting. I stood there facing the brethren with my limp stack of napkins as they laid out all the reasons why it should be one title as opposed to the other. Mercifully our moderator called them to order.

A hush fell over the room. I looked over toward the stoic portrait of Alfred Wegener for a bit of strength. I recounted the events leading to his last days: With a heavy heart but scientific resolve the great polar researcher left his beloved home in the spring of 1930 to lead a grueling, unprecedented scientific expedition into Greenland. His mission was to collect the necessary scientific data to prove his revolutionary hypothesis that the continents as we know them were formerly one great landmass that had broken apart and drifted to their present location. His theory was not only dismissed by the scientific community but ridiculed. And it was to be the research from this historic but ill-fated expedition that would eventually redeem him.

The weather was exceedingly harsh in late October of 1930. Hoarfrost formed like starry ferns on the cavern ceiling of their outpost. Alfred Wegener stepped out into the black night. He examined his conscience, assessing the situation in which his loyal colleagues had been drawn. Counting himself and a loyal Inuit guide named Rasmus Villumsen, there were five men, and the Eismitte station was low on food and supplies. Fritz Loewe, whom he deemed his equal in knowledge and leadership, had several frostbitten toes and could no longer stand. It was a 250-mile walk to the next supply station. Wegener reasoned that Villumsen and he were the sturdiest among them and most likely to survive the long trek and decided to leave on All Saints’ Day.

At dawn on November 1, his fiftieth birthday, he placed his precious notebook inside his coat and optimistically set forth with his team of dogs and Inuit guide. He felt his own strength and the righteousness of his mission. But before long the clear weather shifted as the pair moved through a blistering whirlwind. Snowdrifts followed one another in waves. It was a spectacular vortex of swirling light. White way, white sea, white sky. What could be fairer than such a sight? The face of his wife framed in an immaculate oval of ice? He had given his heart twice, first to her and then to science. Alfred Wegener dropped to his knees. What did he then see? What images might he have projected upon God’s arctic canvas?

My dramatic sense of unity with Wegener was such that I failed to notice a burgeoning disruption. An argument suddenly broke out concerning the validity of my premise.

—He didn’t stumble in the snow.

—He died in his sleep.

—There’s no real proof of that.

—His guide laid him to rest.

—That is conjecture.

—It’s all conjecture.

—It’s not a premise but a prognosis.

—You can’t project such a thing.

—This isn’t science, it’s poetry!

I thought for a moment. What is mathematic and scientific theory but projection? I felt like a straw sinking in Berlin’s River Spree.

What a disaster. Possibly the most antagonistic CDC talk to date.

—Here, here, said our moderator, I think it’s time to call an intermission; perhaps a drink is in order.

—But shouldn’t we hear the end of Twenty-three’s talk? It was the compassionate gravedigger speaking.

I noticed some of the members were already gravitating toward the refreshments and I quickly gained my composure. In measured tones to stake their attention:

—I suppose, I said, that we could let it stand that the last moments of Alfred Wegener have been lost.

Their hearty laughter far surpassed any private hopes of entertaining this endearingly stodgy bunch. All stood as I hastily crammed my scrawled napkins into my pocket and we adjourned to a large drawing room. Each of us had a glass of sherry while our moderator made some closing remarks. Then, as customary, our minister issued a prayer, ending in a moment of silent remembrance.

There were three vans to shuttle the members to their various hotels. As everyone left, the secretary asked me to sign the register.

—Could you give me a copy of your lecture so that I may at least attach it to the minutes? The opening remarks were lovely.

—There actually isn’t anything written, I said.

—But your words, where were they to come from?

— I was sure to pluck them from the air.

She looked at me quite hard and said, Well, then, you must dip back into the air and retrieve something that I can insert into the minutes.

—Well, I do have some notes, I said, feeling for the napkins.

I had never had much conversation with our secretary. She was a widow from Liverpool, consistently dressed in a gray gabardine suit and flowered blouse. Her coat was of brown boiled wool, topped with a matching brown felt hat with an actual hatpin.

—I have an idea, I said. Come with me to the Pasternak café. We can sit at my favorite table beneath a photograph of Mikhail Bulgakov. Then I can tell you what I might have said and you can write it down.

—Bulgakov! Splendid! The vodkas are on me.

—You know, she added, standing before a large photograph of Wegener that was set on an easel, there is a resemblance between these two men.

—Maybe Bulgakov was a bit more handsome.

—And what a writer!

—A master.

—Yes, a master.

I stayed in Berlin a few more days, revisiting places where I had already been, taking pictures I had already shot. I had breakfast at the Café Zoo in the old train station. I was the only customer and sat watching a worker scrape the familiar black silhouette of a camel off the heavy glass door, which aroused my suspicion. Renovation? Closing? I paid my check as if in farewell and crossed the road to the Zoological Garden, entering through the Elephant Gate. I stood before them, somewhat comforted by their solid presence. Two elephants, skillfully carved from Elbe sandstone toward the end of the nineteenth century, kneeling peacefully, supporting two great columns joined by a brightly painted curved roof. A bit of India, a bit of Chinatown, welcoming the astonished visitor.

The zoo was also empty, absent of tourists or the usual schoolchildren. My breath materialized before me and I buttoned my coat. There were some animals about and large birds with tagged wings. A sudden haze drifted over the area. I could just make out giraffes necking between the bare trees, flamingos mating in the snow. Appearing from an unexpected American mist were log cabins, totem poles, bison in Berlin. Wisent immobile shapes like the toys of a child giant. Toys to deftly pluck up like animal crackers and deposit safely into a crate decorated with friezes of bright circus trains carrying aardvarks, dodos, swift dromedaries, baby elephants, and plastic dinosaurs. A box of mixed metaphors.

I asked around if Café Zoo was closing. No one seemed aware that it still existed. The new central train station downgraded the once important Zoo Station, now a regional railway station. Conversations switched to progress. Somewhere in the back of my mind was the whereabouts of an old Café Zoo receipt with the image of the black camel. I was tired. I had a light dinner at my hotel. There was an episode of Law & Order: Criminal Intent dubbed in German on the television. I turned down the sound and fell asleep with my coat on.

On my last morning I walked to the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, with its block-long bullet-riddled walls, a bleak souvenir of World War II. Passing through the portal of angels, one can easily locate where Bertolt Brecht is buried. I noticed that some of the bullet holes had been filled in with white plaster since my last visit. The temperature was dropping and a light snow was falling. I sat before Brecht’s grave and hummed the lullaby Mother Courage sings over the body of her daughter. I sat as the snow fell, imagining Brecht writing his play. Man gives us war. A mother profits from it and pays with her children; they fall one by one like wooden pins at the end of a bowling alley.

As I was leaving I took a photograph of one of the guardian angels. The bellows of my camera were wet with snow and somewhat crushed on the left side, which resulted in a black crescent blotting a portion of the wing. I took another of the wing in close-up. I envisioned printing it much larger on matte paper, and then I would write the words of the lullaby on its white curve. I wondered if these words caused Brecht to weep as he wrung the heart of the mother who was not as heartless as she would lead us to believe. I slipped the photographs into my pocket. My mother was real and her son was real. When he died she buried him. Now she is dead. Mother Courage and her children, my mother and her son. They are all stories now.

Guardian angel, Dorotheenstadt Cemetery

THOUGH RELUCTANT to go home I packed my things and flew to London to make my connection. My flight back to New York was delayed, which I took as a sign. I stood before the departure board and a further delay was posted. Impulsively I rebooked my ticket, took the Heathrow Express to Paddington Station, and from there I took a cab to Covent Garden and checked into a small favored hotel to watch detective shows.

My room was bright and cozy with a small terrace overlooking the London rooftops. I ordered tea and opened my journal, then immediately closed it. I am not here to work, I told myself, but to watch ITV3 mystery dramas, one after another late into the night. I had done this a few years before in the same hotel while ill; delirious nights dominated by a procession of clinically depressed, bad-tempered, heavy-drinking, opera-loving detective inspectors.

To warm up for the evening I watched a vintage episode of The Saint, delighted to follow Simon Templar in his white Volvo, tooling the dark recesses of London and as usual saving the world from imminent disaster. This time with a naïve platinum blonde in a pale cardigan and straight skirt, searching for her uncle—a brilliant professor of biochemistry—who has been kidnapped and is in the clutches of an equally brilliant though malevolent nuclear scientist. It was still early so after a second episode of The Saint, with an entirely different blonde in distress, I walked over to Charing Cross Road and roamed the bookstores. I bought a first edition of Sylvia Plath’s Winter Trees and a copy of Ibsen’s plays. I wound up reading The Master Builder until late afternoon before the fireplace in the hotel library. It was a bit warm and I was nodding off when a man in a tweed overcoat tapped my shoulder, asking if I might be the journalist he was supposed to be meeting.

—No, sorry.

—Reading Ibsen?

—Yes, The Master Builder.

—Hmmm, lovely play but fraught with symbolism.

—I hadn’t noticed, I said.

He stood before the fire for a moment then shook his head and left. Personally, I’m not much for symbolism. I never get it. Why can’t things be just as they are? I never thought to psychoanalyze Seymour Glass or sought to break down “Desolation Row.” I just wanted to get lost, become one with somewhere else, slip a wreath on a steeple top solely because I wished it.

Returning to my room, I bundled up and had tea on the balcony. Then I settled in, giving myself over to the likes of Morse, Lewis, Frost, Wycliffe, and Whitechapel—detective inspectors whose moodiness and obsessive natures mirrored my own. When they had a chop, I ordered same from room service. If they had a drink, I consulted the minibar. I adopted their manner whether entirely engrossed or dispassionately disconnected.

In between shows were upcoming scenes from the highly anticipated Cracker marathon, to be aired on ITV3 the following Tuesday. Though Cracker wasn’t the standard detective show it stands among my favorites. Robbie Coltrane portrays Fitz, the foul-mouthed, chain-smoking, and brilliantly erratic, overweight criminal psychologist. The show was discontinued some time ago, akin to the character’s hard luck, and as it’s rarely aired, the opportunity of twenty-four hours of Cracker was pretty tempting. I deliberated on staying a few more days, but how crazy would that be? No crazier than coming here in the first place, my conscience pipes. I content myself with the generous clips, so relentlessly promoted that I am actually able to piece together a projection of an entire episode.

During a break between Detective Frost and Whitechapel, I decided to have a farewell glass of port in the honesty bar adjacent to the library. Standing by the elevator I suddenly felt a presence beside me. We turned at the same moment and stared at one another. I was stunned to find Robbie Coltrane, as if I’d willed him, some days ahead of the Cracker marathon.

—I’ve been waiting for you all week, I said impetuously.

—Here I am, he laughed.

I was so taken aback that I failed to join him in the elevator and promptly returned to my room, which seemed subtly yet utterly transformed, as if I had been drawn into the parallel quarters of a proper tea-drinking genie.

—Can you imagine the odds of such an encounter? I say to my floral bedspread.

—All things considered, odds-on favorite. But you really should have conjured John Barrymore.

A worthy suggestion but I had no desire to encourage a continuing dialogue. Unlike a channel changer it’s literally impossible to turn off a floral bedspread.

I consulted the minibar and settled on elderberry water and sweet-and-salty popcorn. I hesitated to turn the television back on, as I was certain I would be met with a close-up of Fitz’s face in a dark alcoholic stupor. I wondered if Robbie Coltrane was hitting the honesty bar. I actually thought of going down and peeking but instead rearranged my belongings that were haphazardly stuffed in my small suitcase. In my haste I pricked my finger and was astonished to find the pearl-studded hatpin of the secretary of the CDC lodged between my tee shirts and sweaters. It was the color of iridescent ash and misshapen—more teardrop than pearl. I turned it in the lamplight then wrapped it in a small linen handkerchief embroidered with forget-me-nots, a present from my daughter.

I went over our last exchange outside the Pasternak. We’d had a few shots of vodka. I couldn’t remember anything about a hatpin.

—Where do you think the compass points for our next meeting? I asked.

She seemed evasive and I thought it best not to press. She rummaged through her purse and gave me a hand-colored photograph of the club’s namesake. It was the size and shape of a holy card.

—Why do you think we gather in remembrance of Mr. Wegener? I asked.

—Why, for Mrs. Wegener, she answered without hesitation.

As if it had followed me from Berlin a heavy mist descended on Monmouth Street. From my small terrace I caught the moment when drapes of cloud dropped upon the ground. I had never seen such a thing and lamented I was without film for my camera. On the other hand I was able to experience the moment completely unburdened. I put on my overcoat and turned and said good-bye to my room. Downstairs I had black coffee, kippers, and brown toast in the breakfast room. My car was waiting. My driver was wearing sunglasses.

The mist grew heavier, a full-blown fog, enveloping all we passed. What if it suddenly lifted and everything was gone? The column of Lord Nelson, the Kensington Gardens, the looming Ferris wheel by the river, and the forest on the heath. All disappearing into the silvered atmosphere of an interminable fairy tale. The journey to the airport seemed endless. The outlines of bare trees faintly visible like an illustration from an English storybook. Their naked arms drew across other landscapes: Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and the avenue of plane trees on Jesus Green. The Zentralfriedhof in Vienna where Harry Lime was interred and the Montparnasse cemetery where penciled trees line the paths from grave to grave. Plane trees with pom-poms, dried brown seedpods, swinging ghosts of Christmas ornaments. One could well imagine a former century when a young Scotsman dwelled in such an atmosphere of dropping clouds and shimmering mists and gave it the name of Neverland.

My driver let out a deep sigh. I wondered if my flight would be delayed, but it didn’t matter. No one knew where I was. No one was expecting me. I didn’t mind slowly crawling through the fog in an English cab, black as my coat, flanked by the shivering outline of trees, as if hastily sketched by the posthumous hand of Arthur Rackham.