The Flea Draws Blood

BY THE TIME I got back to New York I had forgotten why I’d left. I attempted to resume my daily routine but was waylaid by an unusually oppressive bout of jet lag. A thick torpor coupled with a surprisingly internal luminosity gave me the impression I had been overcome with a numinous malady transmitted by the Berlin and London fog. My dreams were like outtakes from Spellbound: liquefying columns, straining saplings, and irreducible theorems turning in a swirl of heart-stopping weather. Recognizing the poetic possibilities of this temporary affliction I attempt to rein something in, treading my internal haze in search of elemental creatures or the hare of a wild religion. Instead I am greeted with shuffling face cards with no faces mouthing nothing worth preserving and certainly no cowpoke spinning loopholes. No luck at all. My hands are as empty as the pages of my journal. It’s not so easy writing about nothing. Words caught from a voice-over in a dream more compelling than life. It’s not so easy writing about nothing: I scratch them over and over onto a white wall with a chunk of red chalk.

Sundown, I feed the cats their evening meal, slide on my coat, and wait at the corner for the light to change. Streets are empty, a few cars: red, blue, and a yellow taxi, primary colors saturated by the last of the cold-filtered light. Phrases swoop in on me as if skywritten by tiny biplanes. Replenish your marrow. Have your pockets ready. Wait for the slow burn. Gumshoe phrases bringing to mind the low side-mouthed tones of William Burroughs. Crossing over I wonder how William would decipher the language of my current disposition. There was a time when I could simply pick up the phone and ask him, but now I must summon him in other ways.

’Ino is empty, as I am ahead of the evening rush. It’s not my usual hour but I sit at my same table and have white bean soup and black coffee. Thinking to write something of William I open my notebook, but a pageant of scenes and the faces that inhabited them is quietly paralyzing; couriers of wisdom I was privileged to break bread with. Gone Beats that once ushered my generation into a cultural revolution, though it is William’s distinctive voice that speaks to me now. I can hear him elucidating on the Central Intelligence Agency’s insidious pervasion of our daily life or the perfect bait for catching walleyed pike in Minnesota.

I last saw him in Lawrence, Kansas. He lived in a modest house, with his cats, his books, a shotgun, and a portable wooden medicine cabinet locked away. He sat at his typewriter; the one with the ribbon so used up that sometimes only impressions of words made it to the page. He had a miniature pond with darting red fish and tin cans set up in his backyard. He enjoyed a little target practice and was still a great shot. I purposely left my camera in its sack and stood quietly observing as he took aim. He was somewhat dried and bent, yet he was beautiful. I looked at the bed where he slept and watched the curtains on his window move ever so slightly. Before I said good-bye we stood together before a print of William Blake’s miniature of The Ghost of a Flea. It was an image of a reptilian being with a curved yet powerful spine enhanced with scales of gold.

—That’s how I feel, he said.

I was buttoning my coat. I wanted to ask why but I didn’t say anything.

The ghost of a flea. What was William telling me? My coffee cold, I gesture for another, sketching possible answers then abruptly crossing them out. Instead I opt to follow William’s shadow snaking a winding medina bathed in flickering images of freestanding arthropods. William the exterminator, drawn to a singular insect whose consciousness is so highly concentrated that it conquers his own.

The flea draws blood, depositing it as well. But this is no ordinary blood. What the pathologist calls blood is also a substance of release. A pathologist examines it in a scientific way, but what of the writer, the visualization detective, who sees not only blood but the spattering of words? Oh, the activity in that blood, and the observations lost to God. But what would God do with them? Would they be filed away in some hallowed library? Volumes illustrated with obscure shots taken with a dusty box camera. A revolving system of stills indistinct yet familiar projecting in all directions: a fading drummer boy in white costume, sepia stations, starched shirts, bits of whimsy, rolls of faded scarlet, close-ups of doughboys laid out on the damp earth curling like phosphorescent leaves around the stem of a Chinese pipe.

The boy in white costume. Where did he come from? I didn’t make him up but referenced something. Forgoing a third coffee I close my notes on William, leave some money on the table, and head back home. The answer is in a book somewhere, in my own blessed library. Still in my coat I revisit my book piles, trying not to be sidetracked nor lured into another dimension. I pretend not to notice After-Dinner Declarations by Nicanor Parra or Auden’s Letters from Iceland. I momentarily open Jim Carroll’s The Petting Zoo, essential to anyone in search of concrete delirium, then immediately close it. Sorry, I tell them all, I can’t revisit you now, it’s time to reel myself in.

As I unearth After Nature by W. G. Sebald it occurs to me that the image of the boy in white is on the cover of his Austerlitz. Uniquely haunting, it drew me to the book and thus introduced me to Sebald. Mystery solved, I abandon my search and eagerly open After Nature. At one time the three lengthy poems in this slim volume had such a profound effect on me that I could hardly bear to read them. Scarcely would I enter their world before I’d be transported to a myriad of other worlds. Evidences of such transports are crammed onto the endpapers as well as a declaration I once had the hubris to scrawl in a margin—I may not know what is in your mind, but I know how your mind works.

Max Sebald! He squats on the damp earth and examines a curved stick. An old man’s staff or a humble branch turned with the saliva of a faithful dog? He sees, not with eyes, and yet he sees. He recognizes voices within silence, history within negative space. He conjures ancestors who are not ancestors, with such precision that the gilded threads of an embroidered sleeve are as familiar as his own dusty trousers.

Images hang to dry on a line that stretches around an enormous globe: the reverse of the Ghent altarpiece, a single leaf torn from a wondrous book illustrating an extinct yet glorious fern, a goatskin map of the Gotthard Pass, the coat of a slaughtered fox. He lays out the world in 1527. He gives us a man—the painter Matthias Grünewald. The son, the sacrifice, the great works. We believe it will go on forever, then an abrupt tearing of time, the death of everything. The painter, the son, the strokes all recede, without music, without fanfare, only a sudden and distinct absence of color.

What a drug this little book is; to imbibe it is to find oneself presuming his process. I read and feel that same compulsion; the desire to possess what he has written, which can only be subdued by writing something myself. It is not mere envy but a delusional quickening in the blood. Soon abstracted, the book slips off my lap and I am off, diverted by the calloused heels of a young lad delivering loaves.

He bows his head. As an apprentice to his father, his destiny is decided and there is nothing to do but follow. He bakes bread but dreams of music. One night he rises as his father sleeps. He wraps a loaf and throws it in a sack and steals his father’s boots. Ecstatically he distances himself from his village. He crosses the wide plains, winds through Hindu forests, and scales the white peaks. He journeys until he collapses half starved in a square where a benevolent widow of a famed violinist rescues him. She tends to him and slowly he regains his health. In gratitude he makes himself useful. One evening the young man watches her as she sleeps. He senses her husband’s priceless violin buried in the pit of her memory. Deeply coveting it he picks the lock of her dreams with her own hairpin. He finds the concealed case and triumphantly holds the glowing instrument in his two hands.

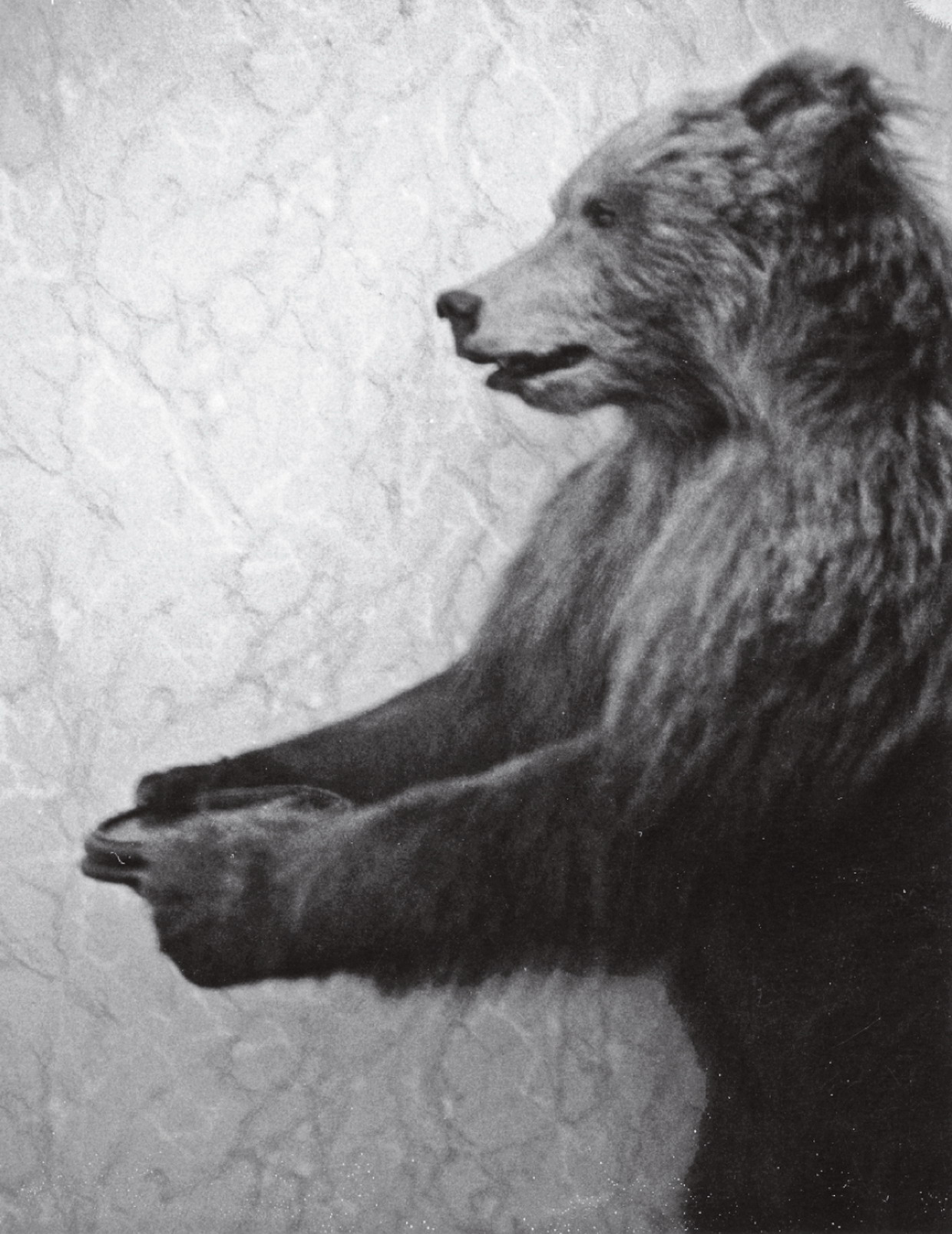

I place After Nature back on the shelf, safely among the many portals of the world. They float through these pages often without explanation. Writers and their process. Writers and their books. I cannot assume the reader will be familiar with them all, but in the end is the reader familiar with me? Does the reader wish to be so? I can only hope, as I offer my world on a platter filled with allusions. As one held by the stuffed bear in Tolstoy’s house, an oval platter that was once overflowing with the names of callers, infamous and obscure, small cartes de visite, many among the many.

Tolstoy’s bear, Moscow