Germantown, Pennsylvania, spring 1954

The Well

IT SNOWED on Saint Patrick’s Day, causing a snag in the annual parade. I lay in bed and watched the snow swirl above the skylight. Saint Paddy’s Day—my namesake day, as my father always said. I could hear the tones of his sonorous voice melding with the snowflakes, coaxing me to rise from my sickbed.

—Come, Patricia, it’s your day. The fever’s passed.

I had spent the first months of 1954 cosseted in the atmosphere of the child convalescent. I was the only child registered in the Philadelphia area with full-blown scarlet fever. My younger siblings held somber vigilance behind my door draped in quarantine yellow. Often I would open my eyes and see the edges of their little brown shoes. Winter was passing and I as their leader had not been able to go out and supervise the building of snow forts or strategize maneuvers over the homemade maps of our child wars.

—Today is your day. We’re going outside.

It was a sunny day with mild winds. My mother laid out my clothes. Some of my hair had fallen out due to a string of high fevers and I’d lost weight from my already lanky frame. I remember a navy-blue watch cap, like the kind fishermen wore, and orange socks in respect for our Protestant grandfather.

My father crouched down several feet away encouraging me to walk.

My siblings willed me on as I plodded unsteadily toward him. Initially weak, my strength and speed returned and I was soon racing ahead of the neighborhood children, long-legged and free.

My brother and sister and I were born in consecutive years after the end of World War II. I was the eldest, and I scripted our play, creating scenarios that they entered wholeheartedly. My brother, Todd, was our faithful knight. My sister Linda served as our confidante and nurse, wrapping our wounds with strips of old linens. Our cardboard shields were covered in aluminum foil and embellished with the cross of Malta, our missions blessed by angels.

We were good children, but our natural curiosity often got us into scrapes. If we were caught tangling with a rival gang or crossing a forbidden thoroughfare, our mother would place us together in one small bedroom, cautioning us not to make a single sound. We appeared to dutifully accept our sentence, but as soon as the door closed we quickly regrouped in perfect silence. There were two small beds and a wide oak bureau with double drawers adorned with carved acorns and large knobs. We would sit in a row before the bureau and I would whisper a code word, signaling our course. Solemnly we would turn the knobs, entering our three-way portal to adventure. I held the lantern high and we scurried aboard our ship, our untroubled world, as children will. Charting new splendors, we played our Game of Knobs, braving new enemies or revisiting moonlit forests opening onto hallowed ground with burnished fountains and remains of castles we had come to know. We played in rapt silence until our mother released us and sent us off to sleep.

It was still snowing; I had to will myself to rise. Perhaps my present malaise is akin to that childhood convalescence, which drew me to bed where I slowly recuperated, read my books, scribbled my first little stories. My malaise. It was time to draw my paper sword, time to cut it to the ground. If my brother were still alive he would surely press me into action.

I went downstairs, eyeing rows of books, despairing of what to choose. A prima donna in the bowels of a wardrobe dripping with dresses, but with nothing to wear. How could I have nothing to read? Perhaps it wasn’t a lack of a book but a lack of obsession. I placed my hand on a familiar spine of green cloth with the gilt title The Little Lame Prince, a favorite of mine as a child—Miss Mulock’s tale of a beautiful young prince whose legs were paralyzed as an infant from a neglectful accident. He is heartlessly locked away in a solitary tower until his true fairy godmother brings him a marvelous traveling cloak that can take him anywhere he wishes. It was a difficult book to find and I never had a copy of my own, and so I read and reread a deteriorating library copy. Then, in the winter of 1993, I received an early birthday gift from my mother along with some Christmas packages. It was to be a difficult winter. Fred was ill and I was plagued with a vague sense of trepidation. I woke up and it was 4 a.m. Everyone was sleeping. I tiptoed down the stairs and unwrapped the package. It was a bright 1909 edition of The Little Lame Prince. She had written we don’t need words on the title page in her then-shaky hand.

I slipped it from the shelf, opening to her inscription. Her familiar writing filled me with longing that was also comforting. Mommy, I said aloud, and I thought of her suddenly stopping what she was doing, often in the center of the kitchen, and invoking her own mother whom she lost when she was eleven years old. How is it that we never completely comprehend our love for someone until they’re gone? I took the book upstairs into my room and placed it with the books that had been hers: Anne of Green Gables. Daddy-Long-Legs. A Girl of the Limberlost. Oh, to be reborn within the pages of a book.

The snow continued to fall. On impulse I bundled up and went out to greet it. I walked east to St. Mark’s Bookshop, where I roamed the aisles, randomly selecting, feeling papers, and examining fonts, praying for a perfect opening line. Dispirited I went to the M section, hoping that Henning Mankell had furthered the adventures of my favorite detective, Kurt Wallander. Sadly I had read them all, but in lingering in the M section I was fortuitously drawn into the interdimensional world of Haruki Murakami.

I had never read Murakami. I had spent the past two years reading and deconstructing Bolaño’s 2666—swept back to front and from every angle. Before 2666, The Master and Margarita had eclipsed all else, and before reading all of Bulgakov there was an exhausting romance with everything Wittgenstein, including fitful attempts to break down his equation. I can’t say I ever succeeded, but the process led me to a possible answer to the Mad Hatter’s riddle: Why is a raven like a writing desk? I pictured the classroom in my country school in Germantown, Pennsylvania. We still had penmanship classes with real ink bottles and wooden dip pens with metal nibs. The raven and the writing desk? It was the ink. I am sure of it.

I opened a book called A Wild Sheep Chase, chosen for its intriguing title. A phrase caught my eye—a maze of narrow streets and drainage canals. I bought it immediately, a sheep-shaped cracker to dunk in my cocoa. Then I walked to nearby Soba-ya and ordered cold buckwheat noodles with yam and began to read. I was so taken by Sheep Chase that I stayed for over two hours, reading over a cup of sake. I could feel my blue-Jell-O funk melting at the edges.

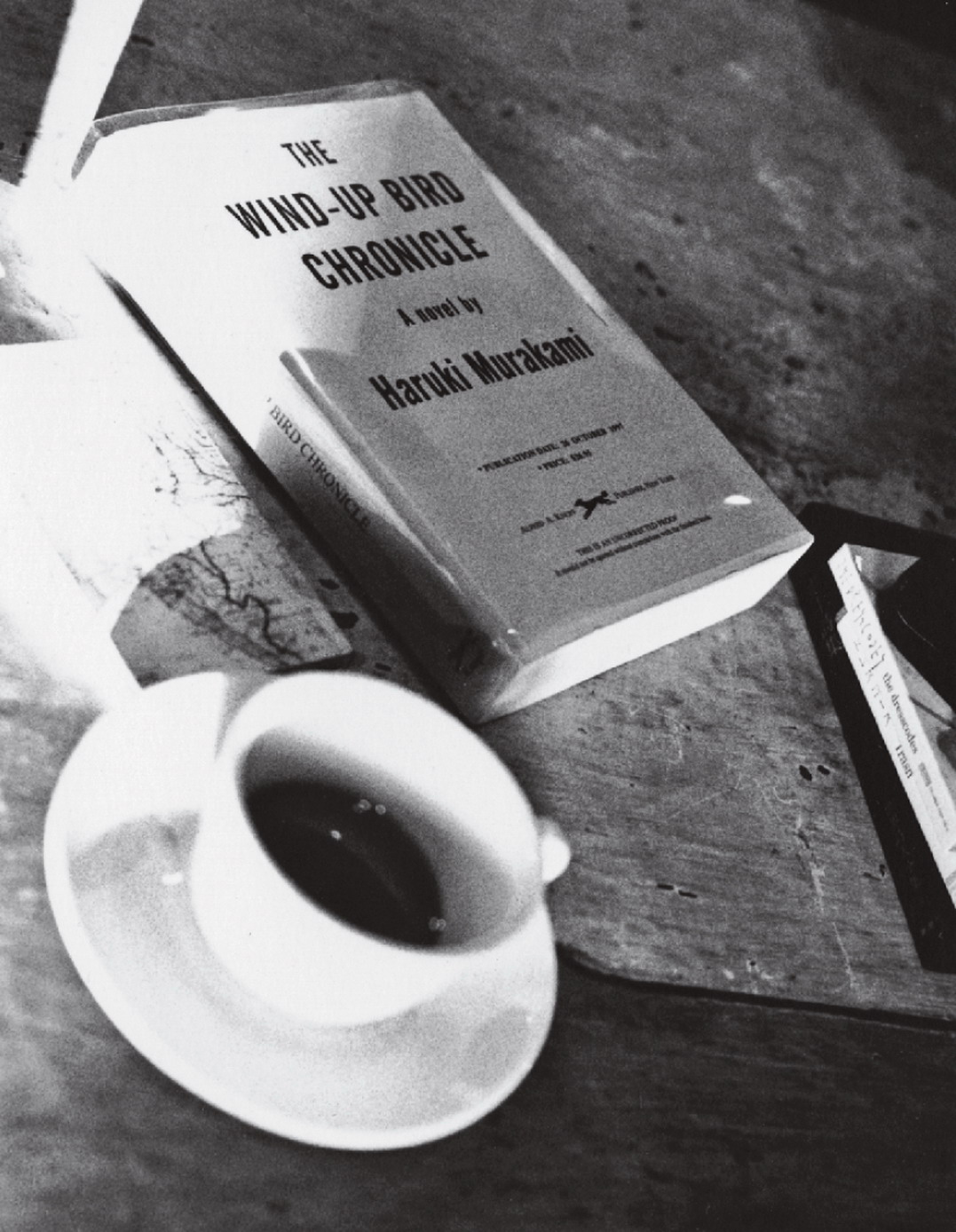

In the weeks to come I would sit at my corner table reading nothing but Murakami. I’d come up for air just long enough to go to the bathroom or order another coffee. Dance Dance Dance and Kafka on the Shore swiftly followed Sheep Chase. And then, fatally, I began The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. That was the one that did me in, setting in motion an unstoppable trajectory, like a meteor hurtling toward a barren and entirely innocent sector of earth.

There are two kinds of masterpieces. There are the classic works monstrous and divine like Moby-Dick or Wuthering Heights or Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus. And then there is the type wherein the writer seems to infuse living energy into words as the reader is spun, wrung, and hung out to dry. Devastating books. Like 2666 or The Master and Margarita. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is such a book. I finished it and was immediately obliged to reread it. For one thing I did not wish to exit its atmosphere. But also, the ghost of a phrase was eating at me. Something that untied a neat knot and let the frayed edges brush against my cheek as I slept. It had to do with the fate of a certain property described by Murakami in the opening chapter.

The narrator is searching for his lost cat near his apartment in the Setagaya ward of the Tokyo prefecture. He makes his way through a narrow alley, winding up at the so-called Miyawaki place—an abandoned house on an overgrown lot, with a paltry bird sculpture and an obsolescent well. There is no indication that he is about to become so wrapped up that it will eclipse all else, and discover within the well an entrance into a parallel world. He is just looking for his cat, but as he is drawn into the murky atmosphere of the Miyawaki place, I was as well. So much so that I could think of little else and would have gladly bribed Murakami to write me a lengthy subchapter exclusively devoted to it. Of course it was impossible to be appeased by writing my own such chapter; it would be mere speculative fiction. Only Murakami could accurately describe every blade of grass in that wretched place. My preoccupation with the property had so completely taken me over that I became possessed with the idea to see it for myself.

I carefully sifted through the last chapters for the passage. Had the phrase indicated that the property would be sold? I finally located the answer in chapter 37. Several phrases beginning with the chilling words: We’ll be getting rid of this place soon. It would indeed be sold and the well filled and sealed. I had somehow skimmed past this fact and would have missed it entirely had it not been for a sense of something wriggling in my memory like a twist of animated string. I was somewhat shaken, for I had projected that the narrator would make it his home, becoming guardian of the well and its portal. I had already reconciled myself to the surreptitious removal of the anonymous bird sculpture that I had grown attached to. It was suddenly gone without explanation and nothing mentioned anywhere of its whereabouts.

I have always hated loose ends. Dangling phrases, unopened packages, or a character that inexplicably disappears, like a lone sheet on a clothesline before a vague storm, left to flap in the wind until that same wind carries it away to become the skin of a ghost or a child’s tent. If I read a book or see a film and some seemingly insignificant thing is left unresolved, I can get remarkably unsettled, going back and forth and looking for clues or wishing I had a number to call or that I could write someone a letter. Not to complain, but just to request clarification or to answer a few questions, so I can concentrate on other things.

There were pigeons moving around above the skylight. I wondered what the wind-up bird looked like. I could picture the bird sculpture, stone indistinctive, poised to fly, but I had no clue about the wind-up bird. Did it possess a tiny bird heart? A hidden spring composed of an unknown alloy? I paced about. Images of other automated birds such as the Die Zwitscher-Maschine of Paul Klee and the mechanical nightingale of the emperor of China came to mind but posed no insight into comprehending the key to the wind-up bird. Normally this would have been the detail of the book that would have intrigued me, but it was overshadowed by my irrational obsession with the ill-fated Miyawaki place, so I stored away that particular rumination for another time.

I sat in my bed watching back-to-back episodes of CSI: Miami led by the stoical Horatio Caine. I momentarily nodded off, not quite asleep, neither here nor there, sliding into that mystically nauseating area in between. Perhaps I could worm my way to the outpost of the cowpoke. If I did I would suspend sarcasm and just listen as if in answer. I saw his boots. I crouched down to see what kind of spurs he had. If they were golden I could be sure he’d traveled far, maybe as far as China. He was swatting an extremely large horsefly. He was about to say something, I could tell. I was squatting low and saw his spurs were nickel with a series of numbers engraved on the outer curve, which I thought may be a possible sequence for a winning lottery ticket. He yawned and stretched out his legs.

—There are actually three kinds of masterpieces, was all he said.

I jumped up, grabbed my black coat and copy of Wind-Up Bird, and headed to Café ’Ino. It was later than usual, happily empty, but a handwritten sign saying Out of Order was taped to the coffee machine. A small blow, but I stayed anyway. I played a game of randomly opening the book, hoping to come across some allusion to the property, like choosing a card from a tarot deck that reflects your current state of mind. Then I amused myself by making lists on its blank endpapers. Two kinds of masterpieces, then I started on the third kind—as dictated by the know-it-all cowpoke. I wrote lists of possibilities, adding, subtracting, and relocating masterpieces like a mad clerk in a subterranean reading room.

Lists. Small anchors in the swirl of transmitted waves, reverie, and saxophone solos. A laundry list of lists actually retrieved in the laundry. Another in the family Bible dated 1955—the best books I ever read: A Dog of Flanders. The Prince and the Pauper. The Blue Bird. Five Little Peppers and How They Grew. And what about Little Women or A Tree Grows in Brooklyn? And what about Through the Looking-Glass or The Glass Bead Game? Which of them qualify for a slot in masterpiece column one, two, or three? Which are merely beloved? And should classics be in their own column?

—Don’t forget Lolita, the cowpoke whispered emphatically.

He was now emerging out of dreamtime, a left-handed version of a numinous voice. In any event I added Lolita. An American classic penned by a Russian, right up there with The Scarlet Letter.

The new girl suddenly appeared at my table.

—Someone is coming to fix the machine.

—That’s good.

—Sorry there is no coffee.

—That’s okay. I have my table.

—And no people!

—Yeah! No people.

—What are you writing?

I looked up at her, somewhat surprised. I had absolutely no idea.

On the way home I stopped at the deli and got a medium black coffee and a slice of hermetically sealed cornbread. It was chilly but I didn’t feel like going inside. I sat on my stoop and held my coffee in both hands until they were warm, then spent several minutes trying to unwind the Saran wrap; easier to strip Lazarus. It suddenly came to me that I failed to enter An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter by César Aira in the list of masterpieces. And what about a sublist of digressional masterworks such as René Daumal’s A Night of Serious Drinking? It was getting all too out of hand. So much easier to write a list of what to pack for a forthcoming journey.

The truth is that there is only one kind of masterpiece: a masterpiece. I shoved my lists into my pocket, got up, and went inside, leaving a trail of cornmeal from stoop to door. My thought processes had the destination futility of a child’s locomotive. Inside, chores needed to be done. I tied up a stack of cardboard for recycling, washed the cats’ water bowls, swept up their scattered dry food, then ate a tin of sardines while standing at the sink, brooding over Murakami’s well.

The well had gone dry, but due to the miraculous opening of the portal by the narrator it consequently brimmed with pure, sweet water. Were they really going to fill it? It was too sacred to fill up solely because it was deemed so through a single sentence in a book. In truth the well seemed so appealing that I wanted to procure it myself, and sit like a Samaritan in hope that the Messiah might return and stop for a drink. There would be absolutely no time frame involved, for armed with such a hope one could be induced to wait forever. Unlike the narrator, I had no desire to actually enter it and go down like Alice into Murakami’s wonderland. I could never conquer my aversion for enclosure, or being underwater. I merely wanted to be in its proximity and be free to drink from it. For like some mad conquistador I craved it.

But how to find the Miyawaki place? Truthfully I wasn’t daunted. We are guided by roses, the scent of a page. Hadn’t I traveled all the way to King’s College after reading of the infamous scuffle between Karl Popper and Ludwig Wittgenstein in the book Wittgenstein’s Poker? So enthralled that with a mere slip of paper scribbled with an enigmatic H-3, I successfully routed out the whereabouts of the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club, where the contentious battle between the two great philosophers occurred. Found, gained entrance, and took several oblique photographs relatively useless to anyone save myself. I can say that it was no easy task. Some additional sleuthing sent me past a concealed farmhouse at the end of a long dirt road to the unkempt grave of Wittgenstein, whose name was all but obliterated by a stippled network of mildew, algae, and lichen, appearing as if strange equations from his own hand.

I suppose it could seem ludicrous to be fixated on a property some twelve thousand miles away; even more problematic the attempt to locate a place that may or may not exist save in the mind of Murakami. I could see if I could channel his channel or just dive into the animate mental pool and call out, Hey, where’s the bird sculpture? or What’s the number of the real estate agent selling the Miyawaki place? Or I could simply ask Murakami himself. I could find his address or write him through his publisher. This was a unique opportunity—a living writer! So much easier than attempting to channel a nineteenth-century poet or an eleventh-century icon painter. Yet wouldn’t that be an act of out-and-out chicanery? Imagine Sherlock Holmes going to Conan Doyle for the answer to a difficult riddle instead of working it out himself. He would never deign to ask Doyle, even if a life depended on it, especially his own. No, I would not ask Murakami. Though I could attempt an aerial CAT scan of his subconscious network or just innocently meet him for coffee where portals connect.

What would the portal look like? I wondered.

Several voices rang out, their answers crisscrossing one another.

—Like a vacant terminal at the Berlin Tempelhof airport.

—Like the open circle in the roof of the Pantheon.

—Like the oval table in the garden of Schiller.

This was interesting. Unrelated portals. Red herring or clue? I went through some boxes, certain that I had taken a few shots of the old Berlin terminal. I had no luck but did find two pictures of the oval table in a small book of poems by Friedrich Schiller. I removed them from their glassine envelope, identical save for the sun blotting more of one shot than the other, taken from an obscure angle to emphasize its resemblance to the mouth of a baptismal font.

In 2009 a few members of the CDC met in the city of Jena, in the east of Thuringia, within the wide valley of the Saale River. It was not an official meeting, more a poetic mission, at the Friedrich Schiller summerhouse, in the garden where he wrote Wallenstein. We were celebrating the oft-forgotten Fritz Loewe, Alfred Wegener’s right-hand man.

Loewe was a tall, sensitive man with slightly protruding teeth and an awkward gait. A classic scientist with meditative fortitude, he joined Wegener for the expedition to Greenland to assist in glaciological work. In 1930 he accompanied Wegener on the grueling journey from Western Station to Eismitte where two scientists, Ernst Sorge and Johannes Georgi, were camped. Loewe suffered severe frostbite and could go no farther than the Eismitte camp and Wegener continued on without him. Toes on both of Loewe’s feet were crudely amputated on-site without anesthesia, leaving him prone in his sleeping bag for the coming months. Unaware their leader had perished, Loewe and his fellow scientists waited from November to May for his return. On Sunday evenings Loewe would read them poems of Goethe and Schiller, filling their ice crypt with the warmth of immortality.

We sat together in the grass by the oval table where Schiller and Goethe once spent hours conversing. We read a passage from Sorge’s essay, “Winter at Eismitte,” that spoke of Loewe’s stoicism and endurance, and then from a selection of the poems he had read during their terrible isolation. It was late May and flowers were in bloom. From the distance we could hear a lilting melody played on a concertina that we affectionately called “Loewe’s Song.” We said our farewells and I continued on, boarding a train to Weimar, in search of the house where Nietzsche had lived under the care of his younger sister.

I taped one of the photographs of the stone table above my desk. Despite its simplicity I thought it innately powerful, a conduit transporting me back to Jena. The table was indeed a valuable element for comprehending the concept of portal-hopping. I was certain that if two friends laid their hands upon it, like a Ouija board, it would be possible for them to be enveloped in the atmosphere of Schiller at his twilight, and Goethe in his prime.

All doors are open to the believer. It is the lesson of the Samaritan woman at the well. In my sleepy state it occurred to me that if the well was a portal out, there must also be a portal in. There must be a thousand and one ways to find it. I should be happy with the one. It might be possible to pass through the orphic mirror like the drunken poet Cègeste in Cocteau’s Orphée. But I did not wish to pass through mirrors, nor quantum tunnel walls, or bore my way into the mind of the writer.

In the end it was Murakami himself who provided me with an unobtrusive solution. The narrator in Wind-Up Bird accomplished moving through the well into the hallway of an indefinable hotel by visualizing himself swimming, akin to his happiest moments. As Peter Pan instructed Wendy and her brothers in order to fly: Think happy thoughts.

I scoured the niches of former joys, halting at a moment of secret exaltation. Though it would take some time, I knew just how to do it. First I would close my eyes and concentrate on the hands of a ten-year-old girl fingering a skate key on a cherished lace from the shoe of a twelve-year-old boy. Think happy thoughts. I would simply roller skate through the portal.