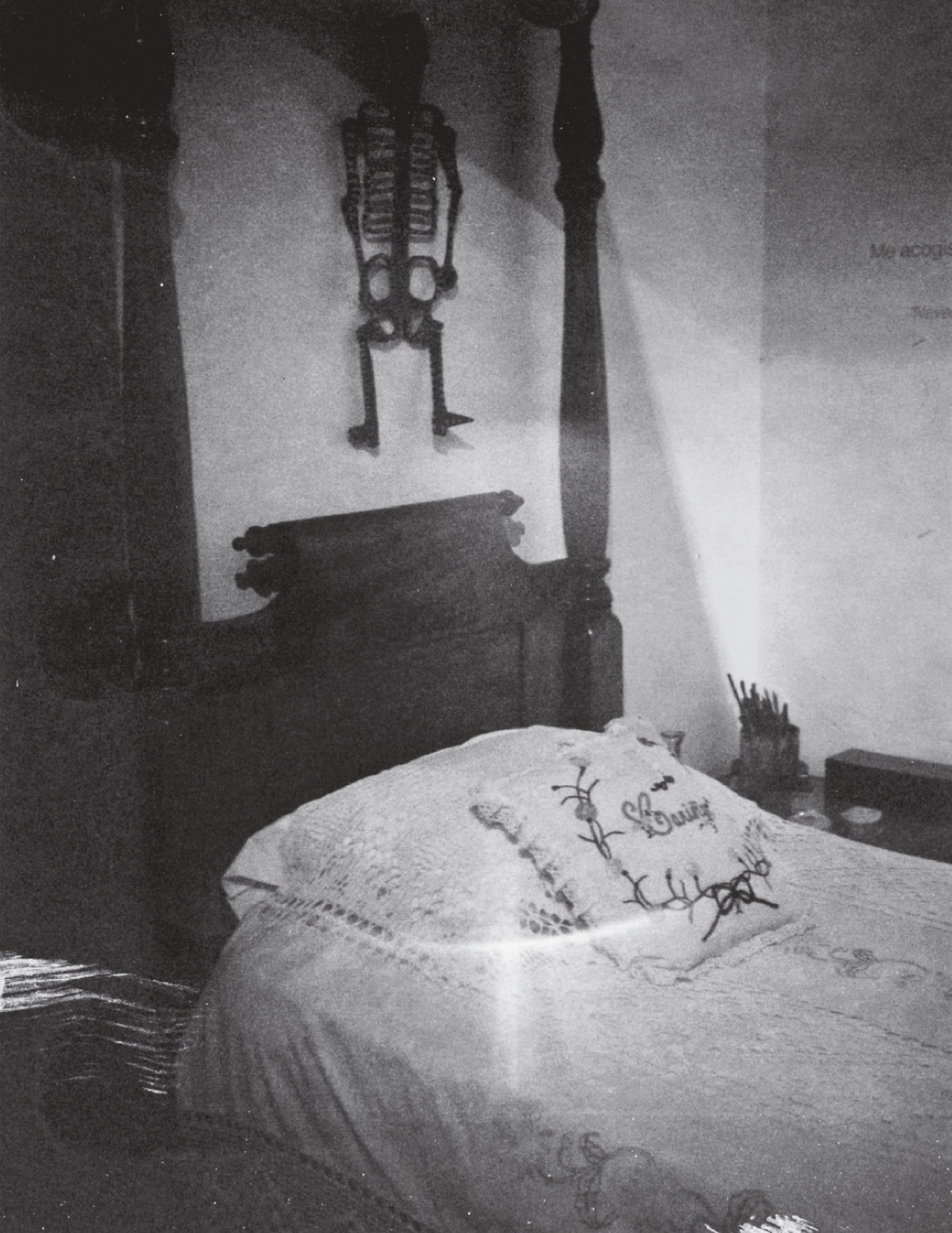

Frida Kahlo’s bed, Casa Azul, Coyoacán

Wheel of Fortune

FOR A TIME I did not dream. My ball bearings somewhat rusted, I went round in waking circles, then on horizontal treks, one touchstone after another, nothing actually to touch. Not getting anywhere, I reverted to an old game, one invented long ago as an insomnia counterattack but also useful on long bus rides as a distraction from carsickness. An interior hopscotch played in the mind, not on foot. The playing field amounted to a kind of a road, a seemingly limitless but actually finite alignment of pyrite squares one must succeed in advancing in order to reach a destination of mythic resonance, say, the Alexandria Serapeum with its entrance card attached to a tasseled velvet rope swaying from above. One proceeds by uttering an uninterrupted stream of words beginning with a chosen letter, say, the letter M. Madrigal minuet master monster maestro mayhem mercy mother marshmallow merengue mastiff mischief marigold mind, on and on without stopping, advancing word by word, square by square. How many times have I played this game, always falling short of the swinging tassel, but at the worst winding up in a dream somewhere? And so I played again. I closed my eyes, let my wrist go limp, my hand circling above the keyboard of my Air, then stopped and my finger pointed the way. V. Venus Verdi Violet Vanessa villain vector valor vitamin vestige vortex vault vine virus vial vermin vellum venom veil, suddenly parting as easily as a vaporous curtain signaling the beginning of a dream.

I was standing in the middle of the same café in its recurring dreamscape. No waitress, no coffee. I was obliged to go to the back and grind some beans and brew them myself. No one was around save the cowpoke. I noticed he had a scar like a small snake moving down his collarbone. I poured us both a steaming mug but avoided his eyes.

—Greek legends don’t tell us anything, he was saying. Legends are stories. People interpret them or attach morals to them. Medea or the Crucifixion, you can’t break them down. The rain and the sun came simultaneously and begat a rainbow. Medea found Jason’s eyes and she sacrificed their children. These things happen, that’s all, the undeniable domino effect of being alive.

He went to relieve himself while I contemplated the Golden Fleece according to Pasolini. I stood at the door and looked out into the horizon. The dusty scape was interrupted by rocky hills devoid of vegetation. I wondered if Medea climbed such rocks after her rage was satiated. I wondered who the cowpoke was. A kind of Homeric drifter, I supposed. I waited for him to exit the john but he was taking too long. There were signs that things were about to shift: an erratic timepiece, the spinning barstool, and an ailing bee levitating above the surface of a small table coated with cream-colored enamel. I thought to save it but there was nothing I could do. I was about to leave without paying for my coffee, then thinking better of it, dropped a few coins on the table next to the expiring bee. Enough for the coffee and a modest matchbox burial.

I shook myself out of my dream, got out of bed, washed my face, braided my hair, found my watch cap and notebook, and headed out still thinking of the cowpoke spewing on about Euripides and Apollonius. Initially he had rubbed me the wrong way, but I had to admit his recurring presence was a comfort. Someone I could find, if need be, in that same scape on the edge of sleep.

As I crossed Sixth Avenue Callas is Medea is Callas looped in rhythm with my boot heels hitting the surface of the street. Pier Paolo Pasolini peers into his casting ball and chooses Maria Callas, one of the most expressive voices of all time, for an epic role with little dialogue and absolutely no singing. Medea does not sing lullabies; she slaughters her children. Maria was not a perfect singer; she drew from the depths of her infinite well and conquered the worlds of her world. But all the heartbreak of her heroines had not prepared her for her own. Betrayed, forsaken, she was left without love, voice, or child, condemned to live out her life in solitude. I preferred to imagine Maria free of the heavy vestments of Medea, the burned queen in a pale yellow sheath. She is wearing pearls. The light floods her Paris apartment as she reaches for a small leather casket. Love is the most precious jewel of all, she whispers, unclasping the pearls that drop from her throat, scales of sorrow that soar and diminish.

Café ’Ino was open but empty; the cook was there alone roasting garlic. I walked over to a nearby bakery, bought a coffee and a piece of crumb cake, and sat on a bench in Father Demo Square. I watched a boy lift his younger sister so she could drink from a water fountain. When she was done he drank his fill. Pigeons were already congregating. As I unwrapped the cake I projected a shambolic crime scene involving frenzied pigeons, brown sugar, and armies of extremely motivated ants. I looked down at the bits of grass protruding through cracked cement. Where are all the ants? And the bees and the little white butterflies we used to see everywhere? And what about the jellyfish and the shooting stars? Opening my journal I glanced at a few drawings. An ant made its way across a page devoted to a Chilean wine palm found in the Orto Botanico in Pisa. There was a small sketch of its trunk but not the leaves. There was a small sketch of heaven but not the earth.

A letter arrived. It was from the director of Casa Azul, home and resting place of Frida Kahlo, requesting I give a talk centering on the artist’s revolutionary life and work. In return I would be granted permission to photograph her belongings, the talismans of her life. Time to travel, to acquiesce to fate. For although I craved solitude, I decided I could not pass on an opportunity to speak in the same garden that I had longed to enter as a young girl. I would enter the house inhabited by Frida and Diego Rivera, and walk through rooms I had only seen in books. I would be back in Mexico.

My introduction to Casa Azul was The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera—a gift from my mother for my sixteenth birthday. It was a seductive book, nourishing a growing desire to immerse myself in Art. I dreamed of traveling to Mexico, to taste their revolution, tread upon their earth, and pray before trees inhabited by their mysterious saints.

I reread the letter with a growing enthusiasm. I thought about the task ahead, and my young self traveling there in the spring of 1971. I was in my early twenties. I saved my money and bought a ticket to Mexico City. I had to make a connection in Los Angeles. I remember seeing a billboard with an image of a woman crucified on a telegraph pole—L.A. Woman. The Doors single “Riders on the Storm” was on the radio. Then, I had no such letter, no real-world plan, but I had a mission and that was good enough for me. I wanted to write a book called Java Head. William Burroughs had told me the best coffee in the world was grown in the mountains surrounding Veracruz, and I was determined to find it.

I arrived in Mexico City and went immediately to the train station where I bought a round-trip ticket. The overnight sleeper was leaving in seven hours. I shoved a notebook, a Bic pen, an ink-stained copy of Artaud’s Anthology, and a small Minox camera into a linen knapsack and left the rest of my stuff in a locker. After changing some money I wandered into the cafeteria down the street from the now-defunct Hotel Ortega and ordered a bowl of codfish stew. I can still see the fish bones swimming in the saffron-colored stock, and a long spine lodged in my throat. I sat there alone, choking. Finally I succeeded in pulling it out with my thumb and forefinger without gagging or drawing attention to myself. I wrapped the bone in a napkin, pocketed it, summoned the waiter, and paid up.

I regained my composure and boarded a bus to Coyoacán in the southwest section of the city, the address for Casa Azul in my pocket. It was a beautiful day and I was filled with anticipation. But I arrived only to find it closed for extensive renovation. I stood numbly before the great blue walls. There was nothing I could do, no one to petition. I was not to enter Casa Azul that day. I walked a few blocks to the house where Trotsky was murdered; through such an intimate act of betrayal Genet would have elevated the assassin to sainthood. I lit a candle at the Church of the Baptist and I sat in a pew with my hands folded, periodically assessing the minor damage to my bone-bruised throat. Back at the train station a porter allowed me to board early. I had a small sleeping compartment. There was a wooden seat that folded down that I draped with a multicolored striped scarf, propping my Artaud book against the peeling mirror. I was really happy. I was on my way to Veracruz, an important center of the coffee trade in Mexico. It was there that I imagined I would write a post-Beat meditation on my substance of choice.

The train ride was uneventful, with no Alfred Hitchcock special effects. I reviewed my plan. I desired no major experience save to find fair lodgings and the perfect cup of joe. I could drink fourteen cups without compromising my sleep. The first hotel I hit was all I could wish for. Hotel Internacional. I was given a whitewashed room with a sink, an overhead fan, and a window that overlooked the town square. I tore an image of Artaud in Mexico from my book and set it on the plaster mantel behind a votive candle. He had loved Mexico and I reasoned he would like being back. After a brief rest I counted out my money, took what I needed, and stuffed the rest in a handwoven cotton sock with a tiny rose embroidered on the ankle.

I hit the street and chose a well-situated bench as to clock the area. I watched as men periodically emerged from one of two hotels and headed down the same street. At midmorning I discreetly tailed one through a winding side street to a café that, despite its modest appearance, seemed the heart of the coffee action. It was not a real café, but it was a real coffee dealer. There was no door. The black-and-white chessboard floor was covered in sawdust. Burlap sacks heavy with coffee beans lined the walls. There were a few small tables, but everyone was standing. There were no women inside. There were no women anywhere. So I just kept walking.

On the second day of my beat, I sauntered in as if I belonged, shuffling through the sawdust. I wore my Wayfarers, acquired at the tobacco shop on Sheridan Square, and a raincoat I had bought secondhand on the Bowery. It was a high-class job, paper-thin though slightly frayed. My cover was journalist for Coffee Trader Magazine. I sat at one of the small round tables and lifted two fingers. I wasn’t sure what this meant, but the men all did it with happy results. I wrote incessantly in my notebook. No one seemed to mind. The next slow-moving hours could only be described as sublime. I noticed a calendar tacked over a sack of overflowing beans marked Chiapas. It was February 14 and I was about to give my heart to a perfect cup of coffee. It was presented to me somewhat ceremoniously. The proprietor stood over me in wait. I offered him a bright, grateful smile. Hermosa, I said, and he smiled broadly in return. Coffee distilled from beans highland grown, entwined with wild orchids and dusted with their pollen; an elixir marrying nature’s extremes.

The rest of the morning I sat watching the men come and go sampling coffee and sniffing out the various beans. Shaking them, holding them to their ears like shells, and rolling them on a flat table with their small, thick hands, as if divining a fortune. Then they would place an order. In those hours, the proprietor and I shared not a word, but the coffee kept coming. Sometimes in a cup, sometimes in a glass. At lunch hour everyone departed, including the proprietor. I rose and inspected the sacks, pocketing a few choice beans as souvenirs.

This regimen was repeated for the next few days. I finally admitted that I was not writing for a magazine but for posterity. I want to write an aria to coffee, I explained without apology, something enduring like the Coffee Cantata of Bach. The proprietor stood before me with his arms folded. How would he respond to such hubris? Then he left, gesturing that I stay put. I had no idea whether Bach’s Coffee Cantata was a work of genius, but his mania for coffee, at a time when it was frowned upon as a drug, is well known. A habit Glenn Gould certainly adopted when he fused with the Goldberg Variations and cried out somewhat maniacally from the piano, I am Bach! Well, I wasn’t anybody. I worked in a bookstore and took leave to write a book I never really wrote.

Soon he reappeared with two plates of black beans, roasted corn, tortillas with sugar, and sliced cactus. We ate together, and then he brought me one last cup. I settled my bill and showed him my notebook. He bade me follow him to his worktable. He took his official seal as a coffee trader and solemnly stamped a blank page. We shook hands knowing most likely we would never meet again, nor would I find coffee as transporting as his.

I packed swiftly, tossing Wind-Up Bird on top of my small metal suitcase. Everything on my list: passport black jacket dungarees underwear 4 tee shirts 6 pairs of bee socks Polaroid film packs Land 250 Camera black watch cap tin of arnica graph paper Moleskine Ethiopian cross. I took my tarot deck out of its worn chamois pouch and drew a card, a little habit before traveling. It was the card of destiny. I sat and sleepily stared at the great revolving wheel. Okay, I thought, that will do.

I awoke dreaming of Pat Sajak. Actually, I couldn’t be sure that it was really Pat Sajak, as I only saw male hands turning oversized cards to reveal particular letters. The peculiar thing is I felt I was revisiting a former dream. The hands would turn over several letters, enough for me to guess a word, but I would come up empty. In my sleep I strained to see the perimeter of the dream. It was all in close-up. There was no way to see any more than I was seeing. In fact the outer edges were slightly distorted, making the material of his fine gabardine suit seem warped, like a nubby raw silk. He also appeared to have a manicure, neat and trim. He was wearing a gold signet ring on his pinky. I should have examined it more closely, as it may have revealed whether it was stamped with his initials.

Later I remembered that Pat Sajak doesn’t turn the letters over in real life. Though it’s debatable whether a game show counts as real life. Everyone knows that Vanna White, not Pat, turns the letters. But I had forgotten and even worse, could not, for the life of me, conjure an image of her face. I was able to summon a parade of shiny sheath dresses but not her face, a fact that bothered me, producing the same uneasiness one might experience if questioned by the authorities about one’s whereabouts on a specific day and having no substantial alibi. I was home, I would have answered feebly, watching Pat Sajak turning letters that formed words I could not make out.

My car arrived. I locked my suitcase, pocketed my passport, and got into the backseat. There was a lot of traffic, and we sat there waiting for a slot outside the Holland Tunnel. I got to thinking about Pat Sajak’s hands. There is a theory that it is good luck to see one’s own hands in a dream. A portent to aspire to, but one’s own hands—not the hands of Pat in close-up doing Vanna’s thing. Then I dozed off and had an entirely different dream. I was in a forest and the trees were laden with sacred ornaments that glittered in the sun. They were too high to reach so I shook them down with a long, wooden staff that was conveniently lying in the grass. When I poked at the leafy branches scores of tiny silver hands rained down and landed by my shoes. They were scuffed-up brown oxfords like I wore in grade school and when I reached down to scoop up the hands I saw a black caterpillar crawling up my sock.

I was disoriented when the car pulled up at Terminal A. Is this where I’m going? I asked. The driver muttered something and I got out, making sure I didn’t leave my watch cap behind, and headed into the terminal. I was dropped off at the wrong end and had to snake through hundreds of people going who knows where to find the right ticket counter. The girl behind the counter insisted I use the kiosk. I don’t know where I’ve been for the last decade, but when did the concept of a kiosk make its way into airline terminals? I want a person to give me my boarding pass, but she insisted I type my information on a screen using the damn kiosk. I had to rummage through my bag to find my reading glasses, and then after answering questions and scanning my passport it suggested I triple my mileage for $108. I pressed NO and the screen froze. I had to tell the girl. She said keep pressing it. Then she suggested I try another kiosk. I was getting agitated, the boarding pass jammed, and the girl was forced to fork around with a friendly-skies pen to dislodge it. Triumphantly she handed it to me in a crinkled, dead-lettuce kind of state. I trekked to Security, took my computer out of its case, removed my cap, watch, and boots, and placed them in a bin with my plastic baggie containing toothpaste, rose cream, and bottle of Powerimmune, and went through the metal detector, then rounded up my stuff again and boarded the plane to Mexico City.

We sat on the runway for about an hour, the song “Shrimp Boats” looping in my head. I started questioning myself. Why did I get so steamed up at check-in? Why did I want the girl to give me a boarding pass? Why couldn’t I just get into the swing of things and get my own? It’s the twenty-first century; they do things differently now. We were about to take off. I was reprimanded for not buckling my seat belt. I forgot to hide the fact by throwing my coat over my lap. I hate being confined, especially when it’s for my own good.

I arrived in Mexico City and got a ride to my district. I checked into my hotel and set up camp in a room on the second floor overlooking a small park. There was a big window in the bathroom and I noticed that the same people I was looking down upon were looking up at me. I had a late lunch, looking forward to Mexican food, but the hotel menu was dominated by Japanese fare. This confused yet strangely wedded me to my sense of place: reading Murakami in a Mexican hotel that specializes in sushi. I settled on shrimp tacos with wasabi dressing and a small shot of tequila. Afterwards I stepped out onto the street and noticed I was on Veracruz Avenue, which gave me hope that I might find good coffee. Roaming around I passed a window filled with flesh-colored plaster hands. I figured I must be where I was supposed to be, though things seemed slightly offset, like an image of Mandrake the Magician in the Sunday comics.

Twilight was approaching. I walked up and down the shaded streets and passed rows of taco trucks and newsstands that sold wrestling magazines, flowers, and lottery tickets. I was tired but stopped in the park across Veracruz Avenue. A medium-size yellow mutt broke away from his master, fairly leaping upon me. I felt my being entered by his deep brown eyes. His master quickly retrieved him but the dog kept straining to keep me in his sights. How easy it is, I mused, to fall in love with an animal. I was suddenly very tired. I had been awake since five in the morning. I returned to my room, which had been tended to in my absence. My clothes were neatly folded and my dirty socks were soaking in the sink. I plopped on the bed still fully dressed. I pictured the yellow dog and wondered if I would see him again. I shut my eyes and slowly faded. The sound of someone speaking through a distorted megaphone brought me back. Disembodied words carried by the wind and landing on my windowsill like a deranged homing pigeon. It was after midnight, a strange hour to be speaking through a megaphone.

I awoke late and had to hustle as I had been invited to the American Embassy. We drank tepid coffee and engaged in a semi-successful cultural conversation. But what struck me was something an intern said a moment before my car drove away. Two journalists, a cameraman, and a child were found murdered in Veracruz the night before. The woman and child were strangled and the two men disemboweled. A disconcerting image of the cameraman thrown in a shallow grave passed through my sights; he sat up in the dark and noticed the blanket on his bed was made of sod.

I was hungry. I had what may be loosely termed huevos rancheros for lunch in a place called Café Bohemia. A bowl of soggy tortilla chips, fried eggs, and green salsa, but I ate it anyway. The coffee was lukewarm with a chocolate aftertaste. I struggled with my few Spanish words and managed to piece together más caliente. The young waiter grinned and made me another, a perfect hot cup of coffee.

That evening I sat in the park, drinking watermelon juice from a conical paper cup bought from a street vendor. Every child laughing made me think of the slain child. Every dog that barked was yellow in my eyes. Back in my room I could hear all the action below. I sang little songs to the birds on my windowsill. I sang for the journalists and the cameraman and the woman and child slain in Veracruz. I sang for those left to rot in ditches, landfills, and junkyards, like fodder for a Bolaño story he had already considered. The moon was nature’s spotlight on the bright faces of the people who gathered in the park below. Their laughter rose with the breeze, and for a brief moment there was no sorrow, no suffering, only unity.

Wind-Up Bird was on the bed next to me but I didn’t open it. Instead I thought about the photographs I was going to take in Coyoacán. I fell asleep and was dreaming I had perfect coordination and swift reflexes. Suddenly I awoke unable to move. My bowels exploding, vomit shooting across my bedding, coupled with a crippling migraine. Incapable of rising I just lay there. Instinctively I felt for my glasses. They were blessedly unscathed.

In the first light I was able to grip the telephone and tell the front desk I was very sick and needed help. A maid came into my room and called down for medicine. She helped me undress and wash, scrubbing my bathroom, changing my sheets. My gratitude to this woman was overflowing. She sang as she rinsed out my soiled clothes, hanging them over the window ledge. My head was still pounding. I held on to her hand. As her smiling face hovered over mine I was pulled into a deep sleep.

I opened my eyes and imagined I saw the maid sitting in a chair by the bed, in a fit of hysterical laughter. She was waving several pages of the manuscript I had slipped under my pillow. I was immediately put off. Not only was she reading my pages, but also they were written in Spanish, seemingly in my own hand, yet incomprehensible to me. I thought about what I had written and could not imagine what had propelled her uproarious state.

—What’s so damn funny? I demanded, though I felt a mounting desire to join in, as her laugh was so appealing.

—It’s a poem, she answered, a poem completely devoid of poetry.

I was taken aback. Was that a good thing or not? She let my pages slide to the floor. I got up and followed her to the window. She pulled on a slim rope tied to a net sack that contained a struggling pigeon.

—Dinner! she cried triumphantly, throwing it over her shoulder.

As she walked toward the door she seemed to grow smaller and smaller, stepping from her dress, no more than a child. I ran to the window and watched her race across Veracruz Avenue. I stood there transfixed. The air was perfect, like milk from the breast of the great mother. Milk that could be suckled by all her children—the babes of Juárez, Harlem, Belfast, Bangladesh. I could still hear the maid laughing, bubbly little sounds that materialized as transparent wisps, like wishes from another world.

In the morning I assessed how I felt. The worst seemed over, but I felt weak and dehydrated and the headache had migrated to the base of my skull. As my car arrived to take me to Casa Azul I hoped that it would stay at bay so I could perform my tasks. When the director welcomed me I thought of my young self, standing before the blue door that did not open.

Although Casa Azul is now a museum it maintains the living atmosphere of the two great artists. In the workroom everything was made ready for me. Frida Kahlo’s dresses and leather corsets were laid out on white tissue. Her medicine bottles on a table, her crutches against the wall. I suddenly felt unsteady and nauseous, but I was able to take a few photographs. I shot quickly in the low light, slipping the unpeeled Polaroids into my pocket.

I was led to Frida’s bedroom. Above her pillow were mounted butterflies so she could look at them as she lay in bed. They were a gift from the sculptor Isamu Noguchi so that she could have something beautiful to view after she lost her leg. I took a photograph of the bed where she had suffered much.

I could no longer hide how sick I felt. The director gave me a glass of water. I sat in the garden with my head in my hands. I felt faint. After conferring with her colleagues she insisted that I rest in Diego’s bedroom. I wanted to protest, but I was unable to speak. It was a modest wooden bed with a white coverlet. I set my camera and the small stack of images onto the floor. Two women tacked a long muslin cloth over the entrance to his room. I leaned over and unpeeled the pictures but could not look at them. I lay thinking of Frida. I could feel her proximity, sense her resilient suffering coupled with her revolutionary enthusiasm. She and Diego were my secret guides at sixteen. I braided my hair like Frida, wore a straw hat like Diego, and now I had touched her dresses and was lying in Diego’s bed. One of the women came in and covered me with a shawl. The room was naturally dark, and thankfully I went to sleep.

The director woke me gently with a concerned expression.

—The people will be arriving soon.

—Don’t worry, I said, I am fine now. But I will need a chair.

I got up and put on my boots and gathered my pictures: the outline of Frida’s crutches, her bed, and the ghost of a stairwell. The atmosphere of sickness glowed within them. That evening I sat before nearly two hundred guests in the garden. I scarcely could say what I talked about, but in the end I sang to them, as I had sung to the birds on my windowsill. It was a song that came to me while I lay in Diego’s bed. It was about the butterflies that Noguchi had given to Frida. I saw tears streaming down the faces of the director and the women who had administered to me with such tender care. Faces I no longer remember.

Late that night there was a party in the park across from my hotel. My headache was completely gone. I packed, then looked out the window. The trees were strung with tiny Christmas lights though it was only the seventh of May. I went down to the bar and had a shot of a very young tequila. The bar was empty, as nearly everyone was in the park. I sat for a long time. The bartender refilled my glass. The tequila was light, like flower juice. I closed my eyes and saw a green train with an M in a circle; a faded green like the back of a praying mantis.

Frida Kahlo’s crutches, Casa Azul

Dress, Casa Azul