How I Lost the Wind-Up Bird

I GOT A MESSAGE from Zak. His beach café was open. All the free coffee I wanted. I was happy for him but hesitated to go anywhere, as it was Memorial Day weekend. The city was deserted, just the way I like it, and there was a new episode of The Killing on Sunday. I decided to visit Zak’s café on Monday and spend the weekend in the city with Detectives Linden and Holder. My room was in a state of complete disarray and I was more unkempt than usual, ready to be comrade to their mute misery, swilling cold coffee in a battered car during a bleak stakeout coming out equally cold. I filled my thermos at the Korean deli, deposited it next to my bed for later, chose a book, and walked over to Bedford Street.

Café ’Ino was empty, so I happily sat and read The Confusions of Young Törless, a novel by Robert Musil. I reflected on the opening line: It was a small station on the long railroad to Russia, fascinated by the power of an ordinary sentence that leads the reader unwittingly through interminable fields of wheat opening onto a path leading to the lair of a sadistic predator contemplating the murder of an unblemished boy.

I read through the afternoon, on the whole doing nothing. The cook was roasting garlic and singing a song in Spanish.

—What is the song about? I asked.

—Death, he answered with a laugh. But don’t worry, nobody dies, it is the death of love.

On Memorial Day I woke early, straightened my room, and filled a sack with what I needed—dark glasses, alkaline water, a bran muffin, and my Wind-Up Bird. At the West Fourth Street Station I got the A train to Broad Channel and made my connection; it took fifty-five minutes. Zak’s was the only café in the lone concession area on the long stretch of boardwalk along Rockaway Beach. Zak was glad to see me and introduced me to everyone. Then as promised he served me coffee free of charge. I stood drinking it, black, watching the people. There was a happy, relaxed atmosphere with an amiable mix of laid-back surfers and working-class families. I was surprised to see my friend Klaus coming toward me on a bicycle. He was wearing a shirt and tie.

—I was in Berlin visiting my father, he said. I just came from the airport.

—Yeah, JFK is very close, I laughed, watching a low-flying plane coming in for a landing.

We sat on a bench watching small children negotiate the waves.

—The main surfer beach is just five blocks down by the jetty.

—You seem to know this area pretty well.

Klaus was suddenly serious.

—You won’t believe this, but I have just bought an old Victorian house here, by the bay. It has a very big yard and I’m planting a huge garden. Something I never could do in Berlin or Manhattan.

We walked across the boardwalk and Klaus got coffee.

—Do you know Zak?

—Everybody knows everybody, he said. It’s a real community.

We said our good-byes and I promised to come see his house and garden soon. In truth I was swiftly falling for this area myself, with its endless boardwalk and brick projects overlooking the sea. I removed my boots and walked along the shore. I have always loved the ocean but never learned to swim. Possibly the sole time I was submerged in water was during the involuntary throes of baptism. Nearly a decade later the polio epidemic was in full swing. A sickly child, I wasn’t allowed to go in shallow lakes or pools with other kids as the virus was thought to be waterborne. My one respite was the sea, for I was allowed to walk and frolic by its edge. In time I developed a self-protective fear of the water, which expanded into fear of immersion.

Fred didn’t swim either. He said that Indians didn’t swim. But he loved boats.

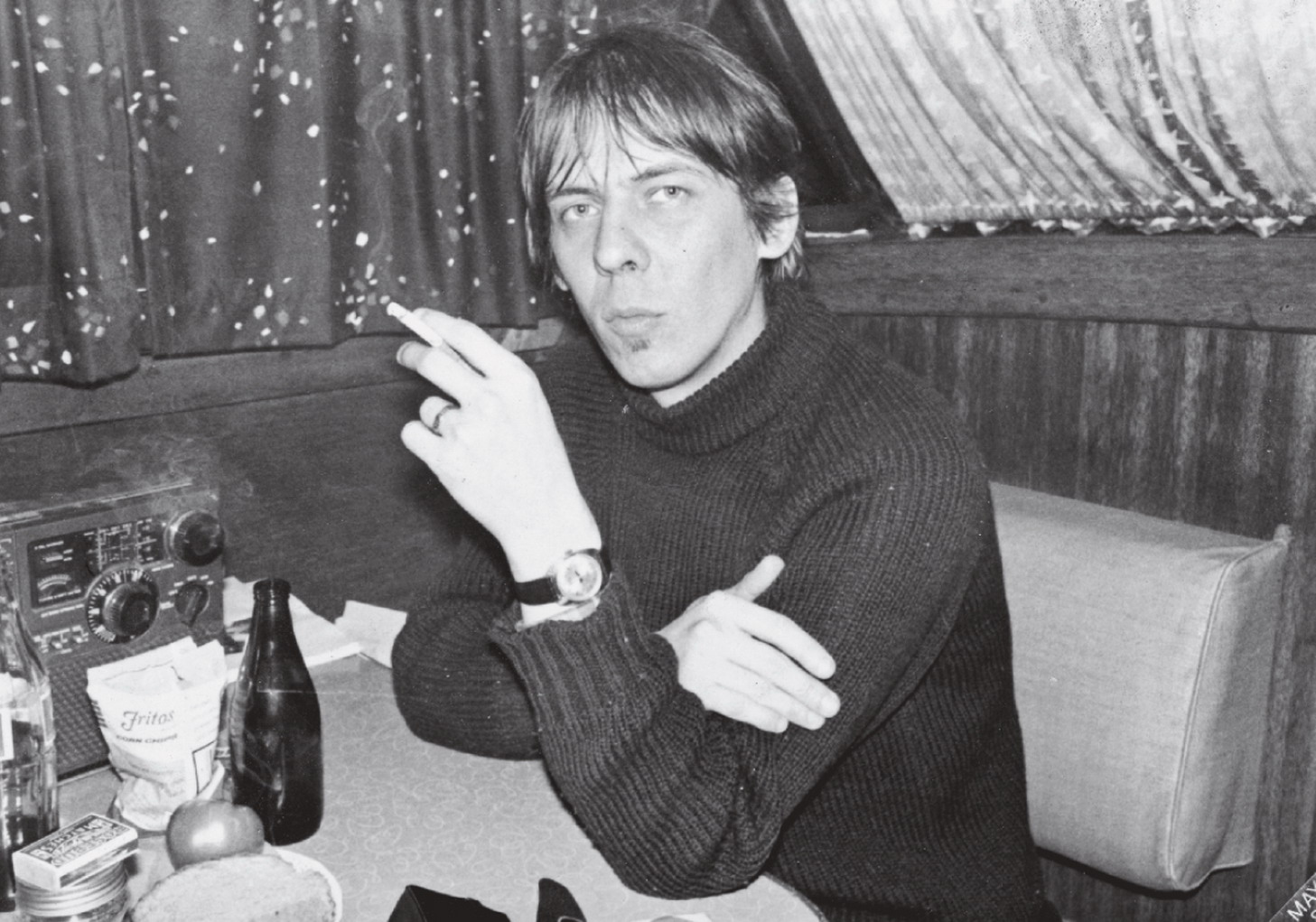

We spent a lot of time looking at old tugboats, houseboats, and shrimp trawlers. He especially liked old wooden boats, and on one of our excursions in Saginaw, Michigan, we found one for sale: a late-fifties Chris Craft Constellation, not guaranteed to be seaworthy. We bought it quite cheaply, hauled it back home, and parked it in our yard facing the canal that led to Lake Saint Clair. I had no interest in boating but worked side by side with Fred stripping the hull, scouring the cabin, waxing and polishing the wood, and sewing small curtains for the windows. Summer nights with my thermos of black coffee and a six-pack of Budweiser for Fred, we’d sit in the cabin and listen to Tigers games. I knew little about sports but Fred’s devotion to his Detroit team obliged me to know the basic rules, our team members, and our rivals. Fred had been scouted as a young man for a shortstop position on the Tigers farm team. He had a great arm but chose to use it as a guitarist, yet his love of the sport never diminished.

It turned out that our wooden boat had a broken axle, and we didn’t have the resources to have it repaired. We were advised to scrap it but we didn’t. To the amusement of our neighbors we decided to keep her right where she was, in the better part of our yard. We deliberated on her name and finally chose Nawader, an Arabic word for rare thing, taken from a passage in Gérard de Nerval’s Women of Cairo. In the winter we covered her with a heavy tarp and when baseball season opened again we removed it and listened to Tigers games on a shortwave radio. If the game was delayed we would sit and listen to cassettes on a boom box. Nothing with words, usually something of Coltrane’s, like Olé or Live at Birdland. On the rare occasion of a rainout we would switch over to Beethoven, whom Fred particularly admired. First a piano sonata, and then with the rain steadily falling, we’d listen to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, following the great composer on an epic walk into the countryside listening to the songs of the birds in the Vienna Woods.

Toward the end of the baseball season Fred surprised me with the official orange-and-blue Detroit Tigers jacket. It was early fall, a bit chilly. Fred fell asleep on the couch and I slipped on the jacket and went out into the yard. I picked up a pear that had fallen from our tree, wiped it off on my sleeve, and sat on a wooden lawn chair in the moonlight. Zipping up my new jacket, I felt the satisfaction of a young athlete receiving his varsity letter. Taking a bite of the pear I imagined being a young pitcher, coming out of nowhere, delivering the Chicago Cubs from their long championship drought by winning thirty-two games in a row. One game more than Denny McClain.

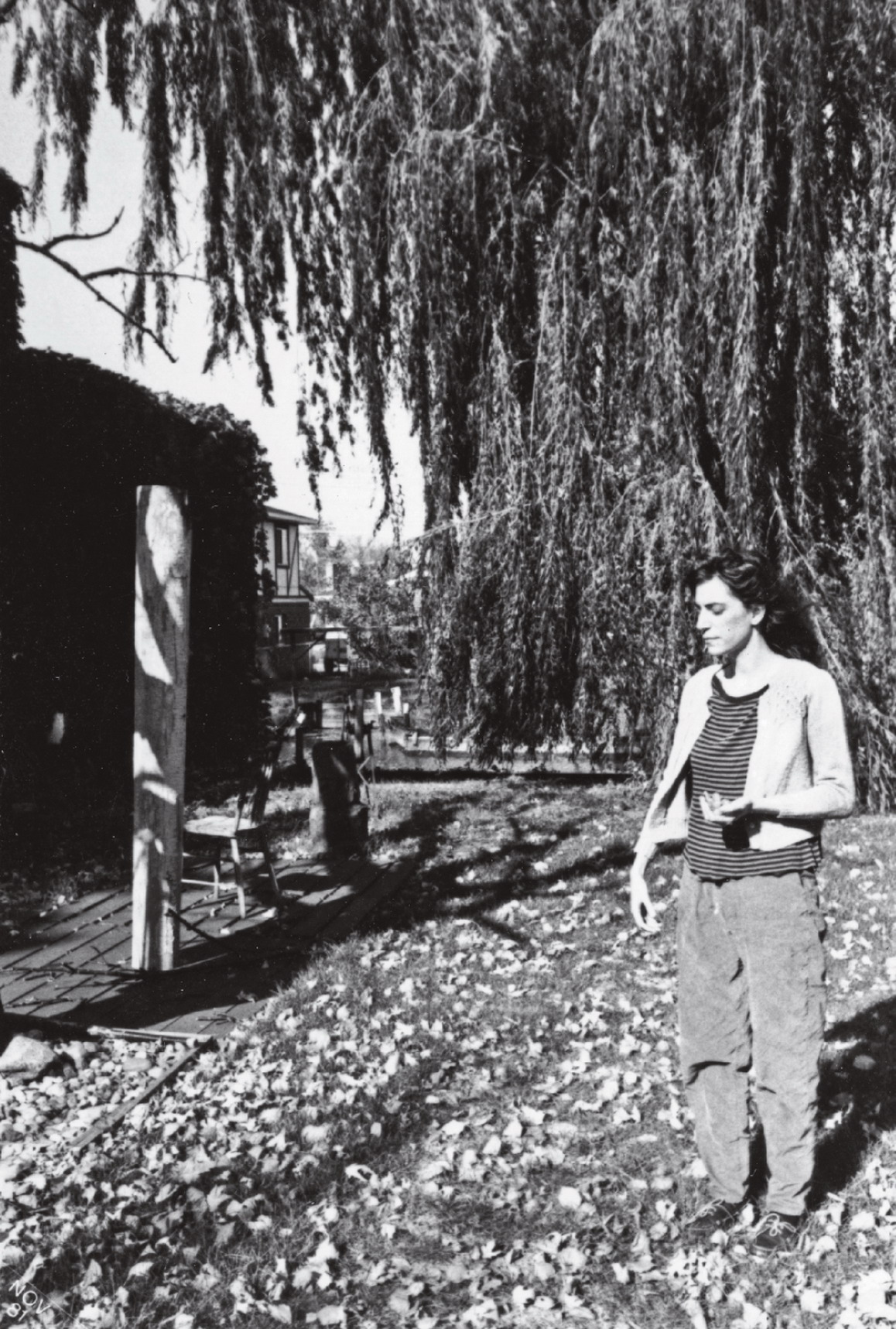

One Indian-summer afternoon the sky turned a distinct chartreuse. I opened our balcony window to get a closer look; I had never seen such a thing. Suddenly the sky went dark; a massive thunderbolt filled our bedroom with a blinding light. For a moment everything went completely silent, followed by a deafening sound. The lightning had struck our immense weeping willow and it had toppled. It was the oldest willow in Saint Clair Shores and its length stretched from the edge of the canal to clear across the street. As it fell, its massive weight crushed our Nawader. Fred was standing at the screen door and I at the window. We watched it happen at the same moment, electrically bound as one consciousness.

I picked up my boots and was admiring the stretch of boardwalk, an infinity of teak, when Zak suddenly appeared with a large coffee to go. We stood there looking out at the water. The sun was going down and the sky turned a pale rose.

—See you soon, I said. Maybe sooner.

—Yeah, this place gets into your blood.

I checked out the surfers and walked up and down the streets between the ocean and the elevated train. As I walked back toward the station I was drawn to a small lot surrounded by a high, weatherbeaten stockade fence. It resembled the kind that secured the Alamo-style forts that my brother and I built as kids. The remains of a cyclone fence propped up the wood palings and a hand-drawn For Sale by Owner sign was tied to the fence with white string. The fence was too high to see what lay behind it, so I stood on my toes and stole a glimpse through a broken slat, like peering into the peephole in the wall of a museum to view Étant donnés—Marcel Duchamp’s last stand.

Willows, Saint Clair Shores

The lot was about twenty-five feet wide and less than a hundred feet deep, the standard size allotted for workers constructing the amusement park in the early twentieth century. Some built makeshift dwelling places, few surviving. I located another weak spot in the fence and got a closer look. The small yard was overgrown, liberally strewn with rusting debris, stacks of tires, and a fishing boat on a bent-up trailer nearly obscuring the bungalow. On the train I tried to read but couldn’t concentrate, I was so taken by Rockaway Beach and the ramshackle bungalow behind the derelict wooden fence that I could think of nothing else.

A few days later I was walking aimlessly and found myself in Chinatown. I suppose I had been daydreaming, for I was surprised as I passed a window display of duck carcasses hanging to dry. I badly needed coffee, so I entered a small café and took a seat. Unfortunately the Silver Moon Café was not a café at all, but once entered, it was nearly impossible to leave. The wood tables and floors were wiped down with tea and its mild fragrance hung in the air. There was a clock with the hour hand missing and a faded picture of an astronaut in a baby blue plastic frame. There was no menu except a laminated card showing four dishes of similar-looking steamed buns, each with a small, raised red, blue, or silver square in the center, like stamps of faded sealing wax. As to the filling it seemed to be a crapshoot.

I was disappointed as I was dying for a cup of coffee, yet I could not get up. The scent of oolong seemed to have the dozy effect of the poppy fields of Oz. An old woman poked me in the shoulder and I blurted: Combo. She mumbled something in Chinese, then left. A small dog sat dutifully beneath a table watching the movements of an elderly man with a yo-yo. He repeatedly tried to lure the dog with his yo-yo skills, but the dog turned his head. I tried not to watch the motion of the yo-yo, up and down and then sideways on the string.

I must have nodded off, for when I opened my eyes a glass of oolong tea and three buns on a narrow bamboo tray had been set before me. The middle bun had a faded blue stamp. I hadn’t a clue as to what that meant but I decided to save it for last. The ones on either side were savory. But the filling in the middle one was a revelation—an elegantly textured red-bean paste that lingered on my breath. I paid the check and the old woman reversed the Open sign as soon as I closed the door, although there were still customers inside as well as the dog and the yo-yo. I had the distinct impression that if I doubled back there would be no trace of the Silver Moon.

Still in need of coffee I stopped at the Atlas Café then walked over to Canal Street to get the subway. I bought a MetroCard from a machine, knowing I would eventually lose it. I much prefer tokens, but those days are gone. I waited for about ten minutes, then boarded the express train to the Rockaways, feeling oddly exhilarated. My brain was fast-forwarding at a speed that could not be translated into mere language. The train was pretty empty, which was good, since I spent much of the ride interrogating myself. By the time it reached Broad Channel, just two stops from Rockaway Beach, I knew what I was going to do.

I stood in front of the fence on tiptoe and peered through the broken slat. All kinds of indistinct memories collided. Vacant lots skinned knees train yards mystical hobos forbidden yet wondrous dwellings of mythical junkyard angels. I had lately been seduced by a piece of abandoned property described in the pages of a book, but this was real. The For Sale by Owner sign seemed to radiate like the electric sign Steppenwolf comes across while on a solitary night walk: Magic Theater. Entrance Not for Everybody. For Madmen Only! Somehow the two signs seemed equivalent. I scribbled the seller’s phone number on a scrap of paper and walked across the road to Zak’s café and got a large black coffee. I sat on a bench on the boardwalk for a long time, looking out at the sea.

This area had thoroughly bewitched me, casting a spell that originated much further back than I could remember. I thought of the mysterious wind-up bird. Have you led me here? I wondered. Close to the sea, though I cannot swim. Close to the train, as I cannot drive. The boardwalk echoed a youth spent in South Jersey with its boardwalks—Wildwood, Atlantic City, Ocean City—more active perhaps but not as beautiful. It seemed the perfect place, with no billboards and few signs of encroaching commerce. And the hidden bungalow! How quickly it had charmed me. I imagined it transformed. A place to think, make spaghetti, brew coffee, a place to write.

Back home I looked at the number I’d written on the scrap of paper but could not bring myself to dial it. I placed it on my night table before my little television set, a strange talisman. Finally I called my friend Klaus and asked him to make the call for me. I suppose a part of me was afraid it was not really for sale or that someone else had already gotten it.

—Of course, he said. I will talk to the owner and find out the details. It would be wonderful if we were neighbors. I’m already renovating my house and it’s only ten blocks from the bungalow.

Klaus dreamed of a garden and found his land. I believed I dreamed of this exact place without knowing it. The wind-up bird had awakened an old yet recurring desire—a dream as old as my café dream—to live by the sea with a ragged garden of my own.

A few days later the seller’s daugher-in-law, a good-natured young woman with two small boys, met me in front of the old blockade fence. We could not enter through the gate, as the owner padlocked it as a safety precaution. Klaus had given me all the information I needed. Because of its condition and some tax liens it was not a bank-friendly property, so the buyer would be obliged to produce cash. Other prospective buyers, seeking a bargain, had grossly underbid. We discussed a fair amount. I told her I would need three months to raise the money, and after some discussion with the owner, all agreed.

—I’m working all summer. When I come back in September I will have the sum I need. I suppose we will have to trust one another, I said.

We shook hands. She removed the For Sale by Owner sign and waved good-bye. Although I was unable to see inside the house I had no doubt that I had made the right decision. Whatever I found to be good I would preserve, and transform what was not.

—I already love you, I told the house.

I sat at my corner table and dreamed of the bungalow. By my calculations I would have the sum I needed to acquire the property by Labor Day. I already had a busy workload and took every other available job I could get from the middle of June through August. I had quite a diverse itinerary of readings, performances, concerts, and lectures. I placed my manuscript into a folder, my pile of scribbled napkins into a large plastic baggie, wrapped my camera in linen, and then locked it all away. I packed my small metal suitcase and flew to London for a night of room service and ITV3 detectives and then I was off to Brighton, Leeds, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Amsterdam, Vienna, Berlin, Lausanne, Barcelona, Brussels, Bilbao, and Bologna. Afterwards I flew to Gothenburg and embarked on a small concert tour of Scandinavia. I plunged happily into work, carefully measuring myself in the heat wave that doggedly pursued me. At night, unable to sleep, I completed an introduction for Astragal, a monograph on William Blake, and meditations on Yves Klein and Francesca Woodman. Every so often I returned to my Bolaño poem, still languishing between 96 and 104 lines. It became something of a hobby, a deeply wrenching one that produced no finished result. How much easier if I had simply assembled small airplane models, applying minute decals and touches of enamel paint.

In early September I returned somewhat exhausted but well satisfied. I had accomplished my mission, losing only one pair of glasses. I had yet one last commitment in Monterrey, Mexico, and then could take a long-needed break. I was among a handful of speakers at a forum of women for women, serious activists whose travails I could barely comprehend. I felt humbled in their presence and wondered how I could possibly serve them. I read poems, sang them songs, and made them laugh.

In the morning a few of us went through two police checkpoints to La Huasteca to a roped-off canyon at the foot of a steep mountain cliff. It was a breathtaking though dangerous place, but we felt nothing but awe. I said a prayer to the lime-dusted mountain, then was drawn to a small rectangular light some twenty feet away. It was a white stone. Actually more tablet than stone, the color of foolscap, as if waiting for another commandment to be etched on its polished surface. I walked over and without hesitation picked it up and put it in my coat pocket as if it were written to do so.

I had thought to bring the strength of the mountain to my little house. I felt an instantaneous affection for it and kept my hand in my pocket in order to touch it, a missal of stone. It was not until later at the airport, as a customs inspector confiscated it, that I realized I had not asked the mountain whether or not I could have it. Hubris, I mourned, sheer hubris. The inspector firmly explained it could be deemed a weapon. It’s a holy stone, I told him, and begged him not to toss it away, which he did without flinching. It bothered me deeply. I had taken a beautiful object, formed by nature, out of its habitat to be thrown into a sack of security rubble.

When I disembarked to change planes in Houston, I went to the bathroom. I was still carrying The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle along with a copy of Dwell magazine. There was a stainless-steel ledge on the right side of the toilet. I placed them there noting what a nice element it was, but as I boarded my connecting plane I realized my hands were empty. I felt quite sad. A heavily marked-up paperback stained with coffee and olive oil, my traveling companion and the mascot of my resurging energy.

The stone and the book: what did it mean? I took the stone from the mountain and it was taken from me. A kind of moral balance, I well understood. But the loss of the book seemed different, more capricious. Quite by accident I had let go of the string attached to Murakami’s well, the abandoned lot, and the bird sculpture. Perhaps because I had found a place of my own and now the Miyawaki place could spin in reverse, happily back to the interconnected world of Murakami. The wind-up bird’s work was done.

September was ending and already cold. I was heading up Sixth Avenue and stopped to buy a new watch cap from a street vendor. As I pulled it on an old man approached me. His blue eyes burned and his hair was white as snow. I noticed that his wool gloves were unraveling and his left hand was bandaged.

—Give me the money you have in your pocket, he said.

Either I am being tested, I thought, or I have wandered into the opening of a modern fairy tale. I had a twenty and three singles, which I placed in his hand.

—Good, he said after a moment, and then returned the twenty.

I thanked him and continued on, more buoyant than before.

There were a lot of people in a hurry on the street, as if last-minute shoppers on Christmas Eve. I hadn’t noticed at first and it seemed they were steadily multiplying. A young woman brushed past me with an armful of flowers. A dizzying perfume lingered, then dispelled, replaced by a vertiginous refrain. I felt conscious of everything: a beating heart, the scent of a song wafting in a conflict of breezes, and the human current heading home.

Three dollars short, richer longer love.

The signs were good. Closing date was October 4. My real estate lawyer attempted to sway me against buying the bungalow due to its ramshackle state and questionable resale value. He failed to comprehend that these were positive qualities in my book. A few days later I paid the sum that I had amassed and was given the key and the deed for an uninhabitable little house on a withered lot, steps away from the train to the right and the sea to the left.

The transformation of the heart is a wondrous thing, no matter how you land there. I heated up some beans and ate quickly, walked to the West Fourth Street Station, and got the A train to the Rockaways. I thought of my brother, our hours on rainy mornings assembling Lincoln Log forts and cabins. We were devoted to Fess Parker, our Davy Crockett. Be sure you’re right, then go ahead was his maxim that soon became ours. He was a good man amounting to much more than a hill of beans. We walked with him as I walk with Detective Linden.

I got off at Broad Channel and boarded the shuttle. It was a mild October day. I loved this short walk from the train up the quiet street, each step closer to the sea. I no longer had to peer longingly at the bungalow through a broken slat. I ignored the No Trespassing sign and for the first time I stepped inside my house. It was empty save a child’s acoustic guitar with broken strings and a black rubber horseshoe. Nothing but good. Small rooms rusted sink vaulted ceiling century-old smells mingling with musty animal smells. I couldn’t stay very long, for the mold and a prevailing dampness ignited my cough yet did not dampen my enthusiasm. I knew exactly what to do: one great room, one turning fan, skylights, a country sink, a desk, some books, a daybed, Mexican-tile floor, and a stove. I sat on my lopsided porch and gazed with girlish happiness at my yard dotted with resilient dandelions. A wind picked up and I could feel the sea within it. I locked my door and closed the gate as a stray cat squeezed through an open slat. Sorry, no milk today, only joy. I stood before the battered blockade fence. My Alamo, I said, and from that moment on my house had a name.