Mu

(Nothingness)

A young man was tramping through the snow with a great bundle of branches tied to his back with a measure of vine. He was bent over from the weight yet I could hear him whistling. Occasionally a branch would slip from the bundle and I would pick it up. The branches were completely transparent, so I filled in their color and texture and added a few thorns. After a time I noticed there were no tracks in the snow. There was no sense of backwards or forwards, only blankness sprinkled here and there with minuscule red droplets.

I tried to map out the fragile spatters, but they kept rearranging themselves, and when I opened my eyes they dissipated completely. I felt around for the channel changer and switched on the TV, careful to avoid any last-year wrap-ups or New Year’s projections. The warm drone of a Law & Order marathon was exactly what I needed. Detective Lennie Briscoe had obviously fallen off the wagon and was gazing at the bottom of a glass of cheap scotch. I got up and poured some mescal in a small water glass and sat at the edge of the bed drinking along with him, watching in stupefied silence, a rerun of a rerun. A New Year’s shot toasting nothing.

I imagined my black coat tapping me on the shoulder.

—Sorry, old friend, I said. I tried to find you.

I called out but heard nothing; crisscrossing wavelengths obscured any hope of feeling out its whereabouts. That’s the way it is sometimes with the calling and the hearing. Abraham heard the demanding call of the Lord. Jane Eyre heard the beseeching cries of Mr. Rochester. But I was deaf to my coat. Most likely it had been carelessly flung on a mound with wheels rolling far away toward the Valley of the Lost.

So foolish, lamenting a coat, such a small thing in the grand scheme. But it wasn’t just the coat; it was an inescapable heaviness reigning over everything, one perhaps easily traceable to Sandy. I can no longer take a train to Rockaway Beach and get a coffee and walk the boardwalk, for there is no more a running train, café, nor boardwalk. Just six months ago I had scrawled I love the boardwalk on a page of my notebook with the effusive sincerity of a teenage girl. Gone is that infatuation, that untapped simplicity embraced. And I am left with a longing for the way things were.

I went down to feed the cats but got waylaid on the second floor. I mechanically took a sheet of drawing paper from my flat file and taped it to the wall. I ran my hand down the skin of its surface. It was nice paper from Florence with an angel watermarked in the center. Searching through my drawing materials I located a box of red Conté crayons and attempted to replicate the pattern that had slipped through my dreamscape into my waking one. It resembled an elongated island. I noticed the cats watching as I executed it. Then I went down to the kitchen, put out their food, adding a treat, and made myself a peanut butter sandwich.

I returned to my drawing but at certain angles it no longer resembled an island. Examining the watermark, more cherub than angel, I remembered another drawing from a few decades ago. On a large sheet of Arches I had stenciled the angel is my watermark, a phrase from Henry Miller’s Black Spring, then drew an angel, crossed it out, and scrawled a message—but Henry, the angel is not my watermark—beneath it. Tapping it lightly, I went back upstairs. I had no idea what to do with myself. Café ’Ino was closed for the holiday. I sat at the edge of the bed eyeing the bottle of mescal. I should really clean up my room, I was thinking, but I knew I wouldn’t.

At sundown I walked over to Omen, a Kyoto country-style restaurant and had a small bowl of red miso soup and complimentary spiced sake. I lingered for a while, ruminating on the coming year. It would be late spring before I could begin to rebuild my Alamo; I would first have to wait until work was under way for my more unfortunate neighbors. Dream must defer to life, I told myself, accidently spilling some of the sake. I was about to wipe the table with my sleeve when I noticed the droplets eerily formed the shape of an elongated island, perhaps a sign. Feeling a surge of investigative energy I paid my check, wished everyone a happy new year, and headed home.

I cleared my worktable, placed my atlas before me, and studied the maps of Asia. Then I opened my computer and searched for the best flights to Tokyo. Every once in a while I would look up at my drawing. I wrote the flights and hotel I wanted on a sheet of paper, the first journey of the year. I would spend some time alone, to write, in the Hotel Okura, a classic sixties hotel near the American Embassy. Afterwards, I’d improvise.

That evening I decided to write to my friend Ace, a modest and knowledgeable movie producer of such films as Nezulla the Rat Monster and Janku Fudo. He speaks little English, but his comrade and translator Dice is so adept at congenial and simultaneous translation that our conversations have always felt seamless. Ace knows where to find the best sake and soba noodles as well as the resting places of all the revered Japanese writers.

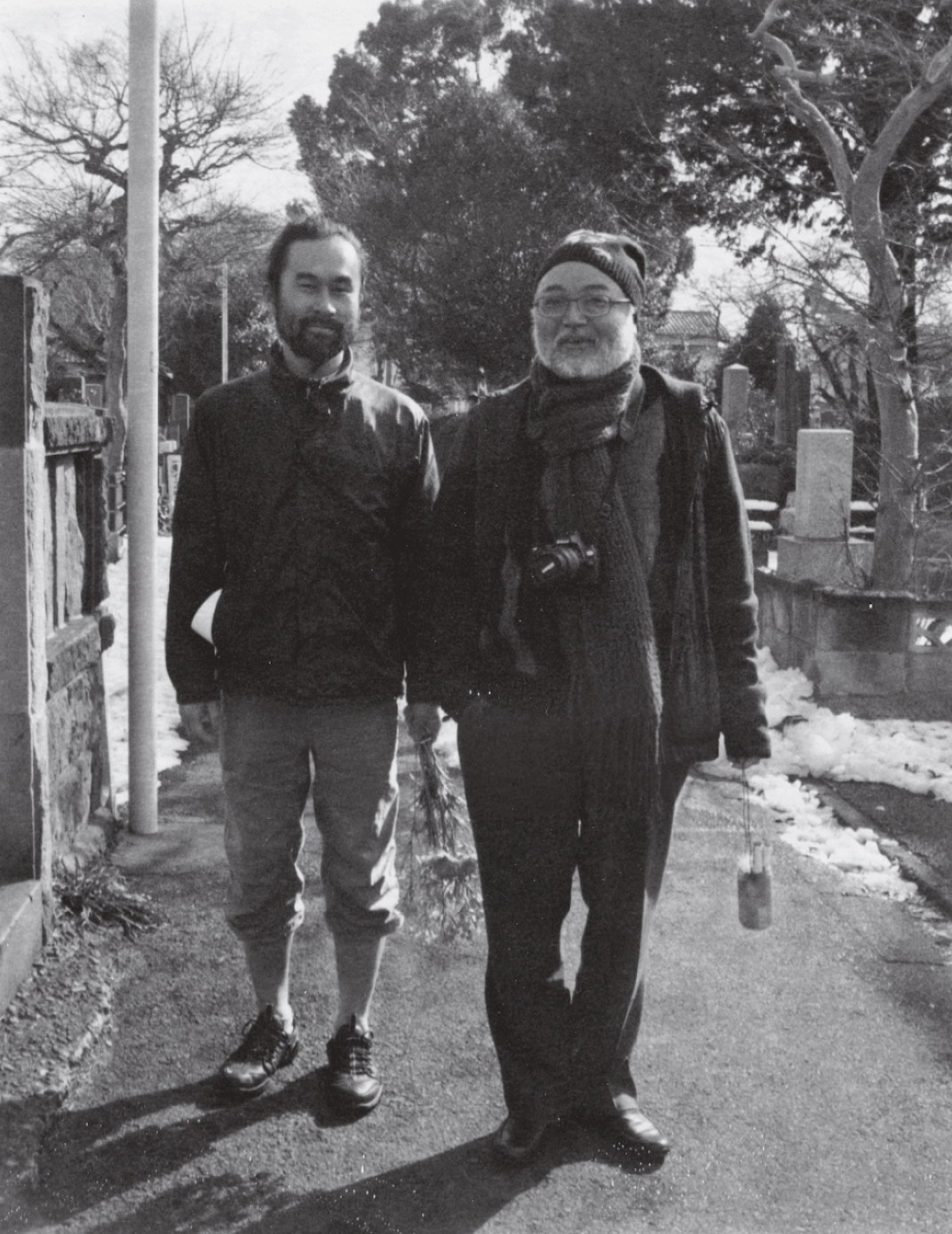

On my last visit to Japan we visited the grave of Yukio Mishima. We swept away dead leaves and ash, filled wooden water buckets and washed the headstone, placed fresh flowers and burned incense. Afterwards we stood in silence. I envisioned the pond that surrounds the golden temple in Kyoto. A large red carp darting beneath the surface joined with another that looked as if it was cloaked in a uniform of clay. Two elderly women in traditional dress approached carrying buckets and brooms. They seemed pleasantly surprised at the state of things, said a few words to Ace, bowed, and went their way.

—They seemed happy to see Mishima’s grave tended to, I said.

—Not exactly, laughed Ace. They were friends of his wife, whose remains are also here. They didn’t mention him at all.

I watched them, two hand-painted dolls receding in the distance. As we were leaving I was given the straw broom I had used to sweep the grave of the man who wrote The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. It leans against the wall in a corner of my room next to an old butterfly net.

I wrote to Ace through Dice. Greetings for the New Year. When I saw you last, it was spring. Now I am coming in the winter. I place myself in your hands. Then a note to my Japanese publisher and translator, finally accepting a long-standing invitation. Lastly to my friend Yuki. Japan had suffered a catastrophic earthquake nearly two years before. The aftermath, still intensely present, eclipsed anything I had ever experienced. From afar I had supported her grassroots relief efforts centering on the needs of orphaned children. I promised to come soon.

I hoped to set aside my impatient woes, be of service, and possibly add a few images to adorn my Polaroid rosary. I was glad to be going somewhere else. All I needed for the mind was to be led to new stations. All I needed for the heart was to visit a place of greater storms. I overturned a card from my tarot deck, and then another, as casually as turning over a leaf. Find the truth of your situation. Set out boldly. I covered all three envelopes with leftover Christmas stamps and slipped them in the letterbox on the way to the deli. Then I bought a box of spaghetti, green onions, garlic, and a tin of anchovies, and made myself a meal.

Café ’Ino looked empty. There were tiny ice formations dripping along the edge of the orange awning. I sat at my table, had my brown toast with olive oil, and opened Camus’s The First Man. I had read it some time ago but was so completely immersed that I retained nothing. This has been an intermittent, lifelong enigma. Through early adolescence I sat and read for hours in a small grove of weed trees near the railroad track in Germantown. Like Gumby I would enter a book wholeheartedly and sometimes venture so deeply it was as if I were living within it. I finished many books in such a manner there, closing the covers ecstatically yet having no memory of the content by the time I returned home. This disturbed me but I kept this strange affliction to myself. I look at the covers of such books and their contents remain a mystery that I cannot bring myself to solve. Certain books I loved and lived within yet cannot remember.

Perhaps in the case of The First Man I was transported more by language than by plot, beguiled by the hand of Camus. But either way, I couldn’t recall a single thing. I was determined to remain present as I read, but was obliged to reread the second sentence of the first paragraph, a spiraling length of words journeying east on the tail of sinewy clouds. I became drowsy—a hypnotic drowsiness that even a cup of steaming black coffee could not compete with. I sat up, shifted to my pending travels, and made a list of things to pack for Tokyo. Jason, the manager of ’Ino, came over to say hello.

—Are you leaving again? he asked.

—Yes, how did you know?

—You’re making lists, he laughed.

It was the same list I always make; yet I was still compelled to write it. Bee socks, underwear, hoodie, six Electric Lady Studio tee shirts, camera, dungarees, my Ethiopian cross, and balm for joint pain. My great quandary was what coat to wear and which books to bring.

That night I had a dream about Detective Holder. We were making our way through a mass grave of engines mattresses stripped laptops—another kind of crime scene. He climbed to the top of an appliance hill, scrutinizing the surrounding area. He had his rabbit twitch going and seemed even more restless than within the confines of The Killing. We climbed over the debris surrounding an abandoned airplane hangar that faced a canal where I had a small tugboat. It was about fourteen feet long, made of wood and hammered aluminum. We sat on some packing crates and watched rusting barges moving slowly in the distance. In my dream I knew it was a dream. The colors of the day were like a painting by Turner—rust, golden air, several shades of red. I could almost make out Holder’s thoughts. We sat there in silence and after a time he got up.

—I have to go, he said.

I nodded. The canal seemed to widen as the barges drew closer.

—Strange proportions, he muttered.

—This is where I live, I said aloud.

I could hear Holder on his cell and his voice growing fainter.

—Tying up some loose ends, he was saying.

For the next few days I searched again for my black coat. A futile effort, though I did find a large canvas bag in the basement filled with old laundry from Michigan—some of Fred’s flannel shirts, slightly musty. I took them upstairs and washed them in the sink. As I rinsed them out I found myself thinking of Katharine Hepburn. She had captivated me as Jo March in George Cukor’s film adaptation of Little Women. Years later when working as a clerk at Scribner’s Bookstore I gathered books for her. She sat at the reading table examining each volume carefully. She wore the late Spencer Tracy’s leather cap, held in place by a green silk headscarf. I stood back and watched as she turned the pages, pondering aloud whether Spence would have liked it. I was a young girl then, not wholly comprehending her ways. I hung Fred’s shirts to dry. In time we often become one with those we once failed to understand.

I had yet to settle on the books I would take. I went back into the basement and located a box of books labeled J—1983, my year of Japanese literature. I took them out one by one. Some were heavily notated; others contained lists of tasks on small slips of graph paper—household needs, packing lists for fishing trips, and a voided check with Fred’s signature. I traced my son’s scribbles on the endpapers of a library copy of Yoshitsune, and reread the first pages of Osamu Dazai’s The Setting Sun, whose fragile cover was adorned with Transformer stickers.

I finally chose a few books by Dazai and Akutagawa. Both had inspired me to write and would serve as meaningful companionship for a fourteen-hour flight. But as it turned out I barely read on the plane. Instead, I watched the movie Master and Commander. Captain Jack Aubrey reminded me so much of Fred that I watched it twice. Midflight I began to weep. Just come back, I was thinking. You’ve been gone long enough. Just come back. I will stop traveling; I will wash your clothes. Mercifully, I fell asleep, and when I awoke snow was falling over Tokyo.

ENTERING THE MODERNIST LOBBY of the Hotel Okura, I had the sensation that my movements were somehow being monitored and that the viewers were hysterical with laughter. I decided to play along and reinforce their amusement by channeling my inner Mr. Magoo, prolonging registration, then shuffling beneath the string of high hexagonal lanterns straight toward the elevator. I went immediately to the Grand Comfort Floor. My room was unromantic but warmly efficient with the special addition of extra oxygen pumped into it. There was a stack of menus on the desk but all were in Japanese. I decided to explore the hotel and its array of restaurants, but I was unable to locate coffee, which was troubling. My body had no sense of time. I didn’t know if it was day or night. Words to the song “Love Potion No. 9” looped as I staggered from floor to floor. I finally ate in a Chinese place that had booths. I had dumplings served in a bamboo box and a pot of jasmine tea. When I returned to my room I hardly had the energy to turn down my blanket. I looked at the small stack of books on the bed table. I reached out for No Longer Human. I vaguely remember sliding my fingers down its spine.

Ghost robe

I followed the motion of my pen, dipping into an inkwell and scratching across the surface of the paper before me. In my dream I was focused and prolific, filling page after page in a room that was not my room in a small rented house in a whole other district. There was an engraved plaque by a sliding panel that opened onto a large closet with a rolled mat for sleeping. Though it was written in Japanese characters I was able to decipher most of it: Please be silent for these are the preserved rooms of the esteemed writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. I knelt down and examined the mat, careful not to draw attention to myself. The screens were open and I could hear the rain. When I rose I felt quite tall, as everything was set low to the ground. There was a shimmering wisp of a robe lying across a rattan chair. As I drew close I could see it was weaving itself. Silkworms were repairing small tears and elongating the wide sleeves. The sight of the spinning worms made me nauseous and, steadying myself, I accidently crushed two or three of them. I watched them struggling half alive in my hand as tiny strands of liquefied silk spread across my palm.

I awoke groping for the water tumbler, spilling its contents. I suppose I wanted to wash off the unfortunate wriggling half-worms. My fingers found my notebook and I sat up abruptly and searched for what I had written, but it seemed I had added nothing, not a single word. I got up and took a bottle of mineral water from the minibar and opened the drapes. Night snow. The sight of it provoked a deep sense of estrangement. Though from what was hard to tell. There was a kettle in my room, so I prepared tea and ate some biscuits I had pocketed in the airport lounge. Soon the sun would rise.

I sat at the portable metal desk before my open notebook, straining to get something down. On the whole I thought more than I wrote, wishing I could just transmit straightaway to the page. When I was young I had the notion to think and write simultaneously, but I could never keep up with myself. I gave up the pursuit and I wrote in my head as I sat with my dog by a secret stream incandescent with rainbows, a mix of sun and petrol, skimming the water like weightless Merbabies with iridescent wings.

The morning was still overcast but the snowfall had lightened. I wondered if extra oxygen was really being pumped into the air and whether it escaped whenever I opened the door. Down below crossing the parking lot was a procession of girls in elaborate kimonos with long swinging sleeves. It was Coming of Age Day, a scene of flurrying innocence. Poor little feet! I shivered as they trod through the snow in their zori sandals, yet their body language suggested squeals of laughter. Half-formed prayers like streamers found their mark and trailed the hems of their colorful kimonos. I watched until they disappeared around a bend into the arms of an enveloping mist.

I returned to my station and gazed at my notebook. I was determined to produce something despite an inescapable lassitude, no doubt due to the deeper effect of travel. I could not resist closing my eyes for just a moment and was instantaneously greeted with an expanding lattice that shook soundly, blanketing the edge of an impeccable maze with a torrent of petals. Horizontal clouds formed above a distant mountain: the floating lips of Lee Miller. Not now, I said half aloud, for I was not about to get lost in some surreal labyrinth. I was not thinking about mazes and muses. I was thinking about writers.

After our son was born Fred and I stayed close to home. We often went to the library, checked out stacks of books and read through the night. Fred was fixated on every aspect of aviation and I was immersed in Japanese literature. Rapt in the atmosphere of certain writers I converted the small storage room, adjacent to our bedroom, into my own. I bought yards of black felt and covered the floor and baseboards. I had an iron teapot and a hot plate and four orange crates for my books, that Fred painted black. I sat cross-legged on the black-felt-covered floor before a long, low table. On winter mornings the view outside the window seemed drained of color with slim trees bending in the white wind. I wrote in that room until our son came of age and then it became his room. After that I wrote in the kitchen.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and Osamu Dazai wrote the books that drove me to such wondrous distraction, the same books that are now on the bed table. I was thinking of them. They came to me in Michigan and I have brought them back to Japan. Both writers took their own lives. Akutagawa, fearing he had inherited his mother’s madness, ingested a fatal dose of Veronal and then curled up in his mat next to his wife and son as they slept. The younger Dazai, a devoted acolyte, seemed to take on the hair shirt of the master, failing at multiple suicide attempts before drowning himself, along with a companion, in the muddied, rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal.

Akutagawa intrinsically damned and Dazai damning himself. At first I had it in mind to write something of them both. In my dream I had sat at the writing table of Akutagawa, but I hesitated to disturb his peace. Dazai was another story. His spirit seemed to be everywhere, like a haunted jumping bean. Unhappy man, I thought, and then chose him as my subject.

Deeply concentrating, I attempted to channel the writer. But I could not keep up with my thoughts, as they were swifter than my pencil and wrote nothing. Relax, I told myself, you have chosen your subject or your subject has chosen you, he will come. The atmosphere surrounding me was both animated and contained. I felt a growing impatience coupled with an underlying anxiety that I attributed to a lack of coffee. I looked over my shoulder as if expecting a visitor.

—What is nothing? I impetuously asked.

—It is what you can see of your eyes without a mirror, was the answer.

I was suddenly hungry but had no desire to leave my room. Nonetheless I went back down to the Chinese restaurant and pointed to a picture of what I wanted on the menu. I had shrimp balls and steamed cabbage dumplings wrapped in leaves in a bamboo basket. I drew a likeness of Dazai on the napkin, exaggerating his unruly hair atop a face at once handsome and comic. It occurred to me that both writers shared this charming characteristic, hair that stood on end. I paid my check and got back into the elevator. My sector of the hotel seemed inexplicably empty.

Sundown, dawn, full night, my body had no sense of time and I decided to accept it and proceed Fred’s way. Following no hands. Within a week I would be in the time zone of Ace and Dice, but these days were entirely my own with no design other than the hope of filling a few pages with something of worth. I crawled under the covers to read but passed out in the middle of Hell Screen and missed the balance of the afternoon and sunset transitioning into evening. When I awoke it was too late to dine, so I grabbed some snacks from the minibar—a bag of fish-shaped crackers dusted with wasabi powder, an oversized Snickers bar, and a jar of blanched almonds. Dinner downed with ginger ale. I laid out some clothes and showered, then decided to go out, if only to walk around the parking lot. Covering my damp hair with a watch cap, I went out and followed the path the young girls had taken. There were steps carved into a small hill that seemed to lead nowhere.

Unconsciously I had already developed some semblance of routine. I read, sat before the metal desk, ate Chinese food, and retraced my own footsteps in the night snow. I attempted to quell any recurring agitation with a repetitive exercise: writing the name Osamu Dazai over and over, nearly a hundred times. Unfortunately, the page spelling out the name of the writer amounted to nothing. My regimen slipped into a pointless web of haphazard calligraphy.

Yet somehow I was drawing closer to my subject—Dazai the dazed one, a stumblebum, an aristocratic tramp. I could see the spikes of his unruly hair and feel the energy of his accursed remorse. I got up, boiled a pot of water, drank some powdered tea, and stepped into a cloud of well-being. Closing my journal I placed several sheets of hotel stationery before me. Taking long, slow breaths I emptied myself and began again.

The young leaves did not fall from the trees but clung desperately throughout winter. Even as the wind whistled, to the astonishment of everyone they had the audacity to remain green. The writer was unmoved. The elders regarded him with disgust, to them he is a wobbling poet on the brink. In turn he regarded them with contempt, imagining himself an elegant surfer riding the crest, never crashing.

The ruling class, he shouts, the ruling class.

He wakes in pools of sweat, his shirt stiff with salt. The tuberculosis he has carried since youth has calcified as tiny seeds—minute black sesame liberally seasoning his lung. A bout of drink sets him off: strange women, strange beds, a horrid cough spraying kaleidoscopic stains across foreign sheets.

I could not help it, he cries. The well begs for the lips of the drunkard. Drink me drink me, it calls. Insistent bells are tolling. A litany of He.

His sinewy arms tremble beneath billowing sleeves. He bends over his low table composing small suicide notes that somehow become something else entirely. Slowing his blood, the beating of his heart, with the forbearance of a fasting scribe he writes what has to be written, conscious of the movement of his wrist as words spread across the surface of the paper like an ancient magic spell. He savors his one joy, a cold pint of miruku that moves through his system like a transfusion of milky corpuscles.

The sudden brightness of dawn startles him. He staggers into the garden; bright blooms stick out their fiery tongues, sinister oleanders of the red queen. When did the flowers become so sinister? He tries to remember when it all went wrong. How the threads of his life unraveled like winding linen from the unbound feet of a fallen consort.

He is overcome with the disease of love, the drunkenness of generations past. When are we ourselves, he wonders, trudging through the snow-covered banks, his coat illuminated by moonlight. Long pelts, lined heavy silk the color of aged parchment, with the words Eat or Die written in his own distinct hand on the sleeves, vertically on the back and beneath the collar running down his left side over his heart. Eat or Die. Eat or Die. Eat or Die.

I paused, wishing I could hold such a coat in my hands, and realized the hotel phone was ringing. It was Dice calling on behalf of Ace.

—The phone rang many times. Have we disturbed you?

—No, no, I am happy to hear from you. I’ve been writing something for Osamu Dazai, I said.

—Then you will be happy with our itinerary.

—I am ready. What first?

—Ace has booked dinner at Mifune, then we can plan for tomorrow.

—I will meet you in the lobby in one hour.

I was delighted by the choice of Mifune, a sentimental favorite, themed on the life of the great Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune. Most likely, much sake would be consumed and perhaps a special soba dish prepared for me. My solitude could not have been severed in a more fortuitous way. I quickly straightened my things, slipped an aspirin into my pocket, and reunited with Ace and Dice. Just as I supposed, the sake flowed. Drenched in the atmosphere of a Kurosawa film, we immediately picked up the thread of a year ago—graves, temples, and forests in the snow.

The next morning, they picked me up in Ace’s two-tone Fiat resembling a red-and-white saddle shoe. We drove around looking for coffee. I was so happy to finally have some that Ace had them fill a small thermos for later.

—Didn’t you know, asked Dice, that in the renovated annex of the Okura they serve a full American breakfast?

—Oh no, I laughed. I bet I missed out on vats of coffee.

Ace is the one person I would accept an itinerary from, as his choices consistently correspond with my own desires. We drove to the Kōtoku-in, a Buddhist temple in Kamakura, and paid our respects to the Great Buddha that loomed above us like the Eiffel Tower. So mystically intimidating that I only took one shot. When I unpeeled the image it revealed that the emulsion was faulty and had not captured his head.

—Perhaps he is hiding his face, said Dice.

On the first day of our pilgrimage I barely used my camera. We laid flowers by the public marker for Akira Kurosawa. I thought of his great body of work from Drunken Angel to his masterpiece Ran, an epic that might have caused Shakespeare to shudder. I remember experiencing Ran in a local theater in the outskirts of Detroit. Fred took me for my fortieth birthday. The sun had not yet set and the sky was bright and clear. But in the course of the three-hour film, unbeknownst to us, a blizzard struck, and as we exited the theater a black sky whitewashed by a vortex of snow awaited us.

Kita-Kamakura Station, winter

—We are still in the film, he said.

Ace consulted a printed map of Engaku-ji cemetery. As we passed the train station, I stopped to watch the people as they patiently waited, then crossed over the railway line. An old express rattled past, as if clattering hooves of past scenes galloped from brutal angles. Shivering, we searched for the grave of the filmmaker Ozu, a difficult undertaking, for it was isolated in a small enclave on higher ground. Several bottles of sake were placed before his headstone, a black granite cube containing only the character mu, signifying nothingness. Here a happy tramp could find shelter and drink himself into oblivion. Ozu loved his sake, said Ace; no one would dare to open his bottles. Snow covered everything. We mounted the stone steps and placed some incense and watched the smoke pour, then hover perfectly still, as if anticipating how it might feel to be frozen.

Scenes of films flickered through the atmosphere. The actress Setsuko Hara lying in the sun, her open clear expression, and her radiant smile. She had worked with both masters, first with Kurosawa and then six films with Ozu.

—Where is she resting? I asked, thinking to bring an armful of huge white chrysanthemums and lay them before her marker.

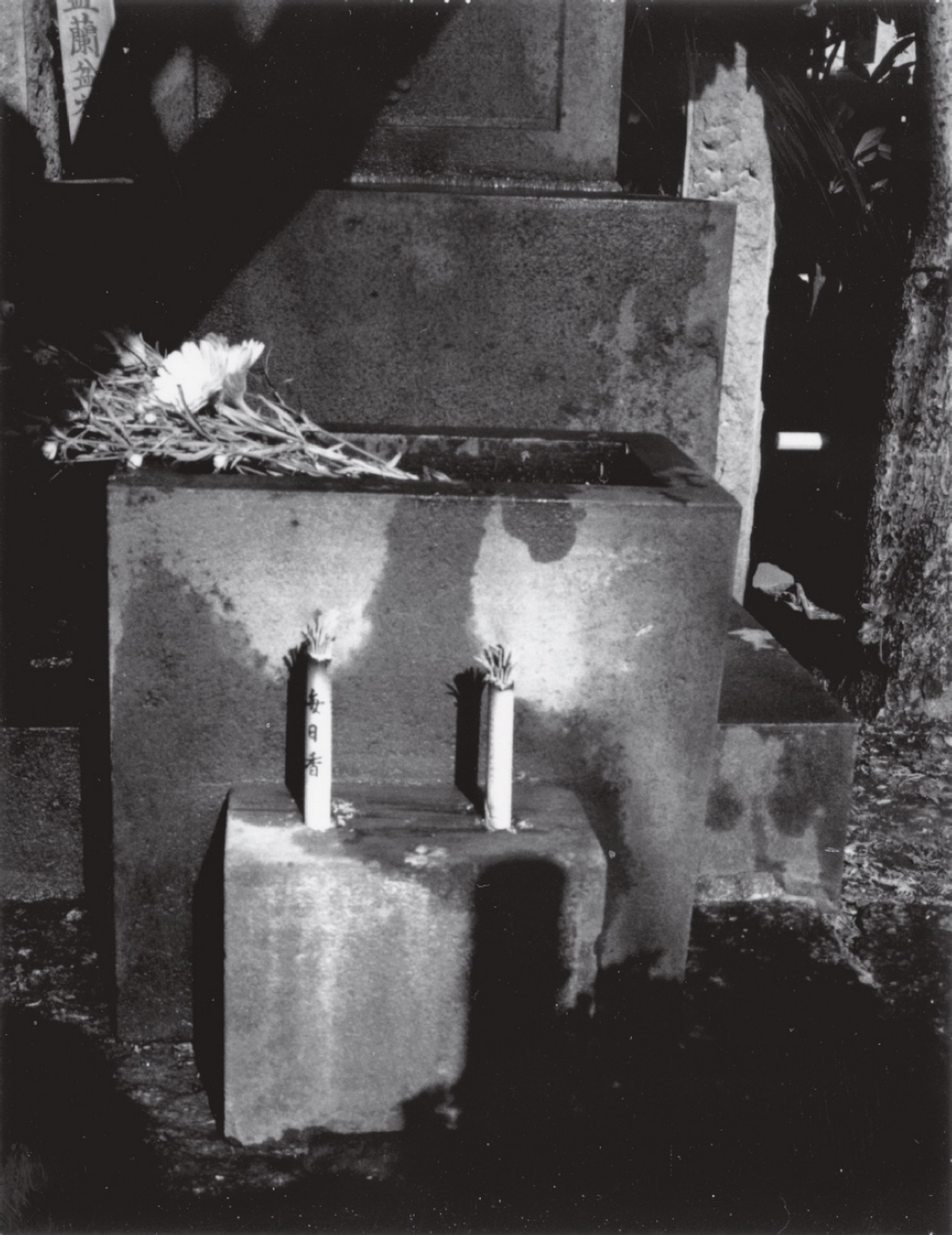

Incense burner, grave of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

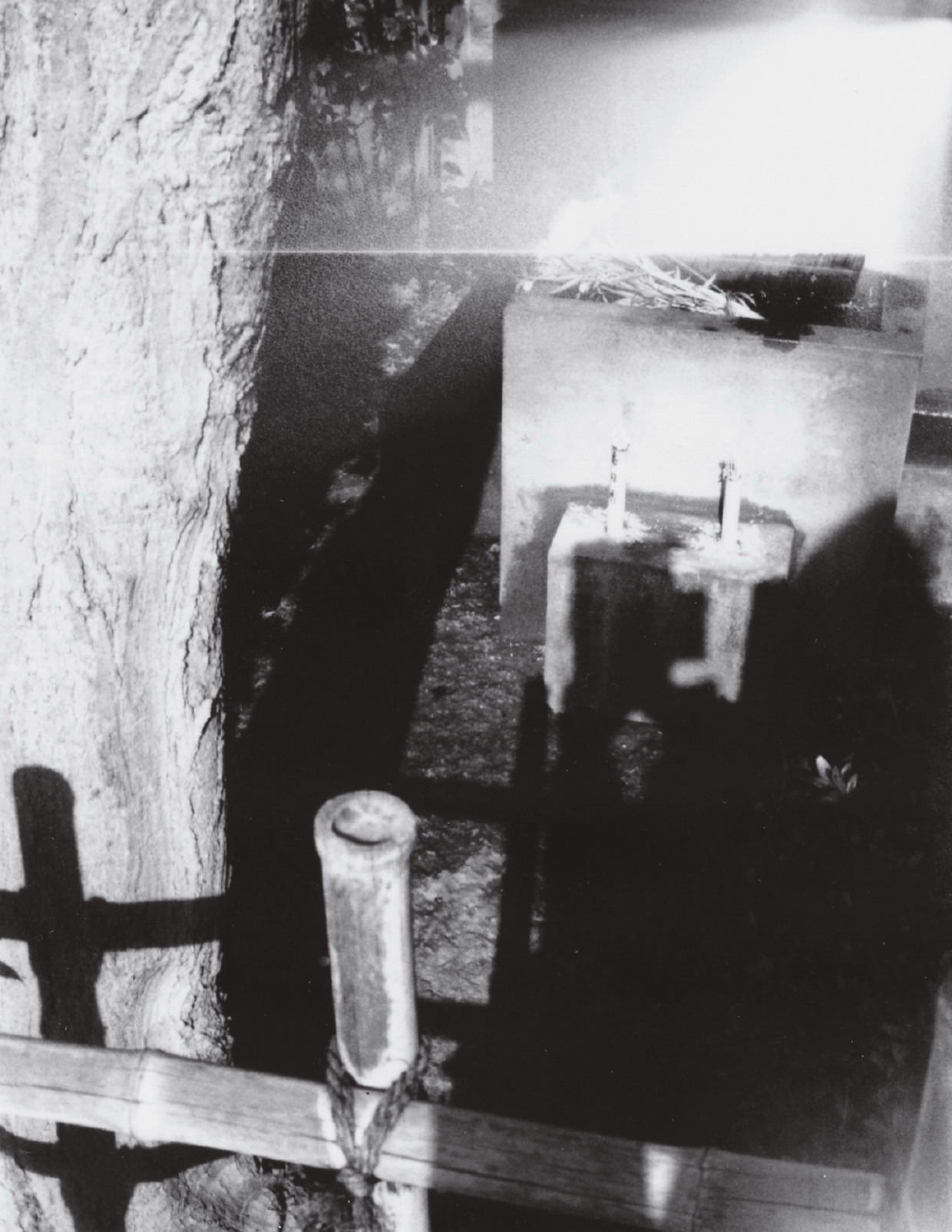

Departing gravesite

—She is still alive, Dice translated. Ninety-two years old.

—May she live to be one hundred, I said. Faithful to herself.

The next morning was overcast, the shadows oppressive. I swept the grave of Dazai and washed the headstone, as if it were his body. After rinsing the flower holders I placed a fresh bunch in each one. A red orchid to symbolize the blood of his tuberculosis and small branches of white forsythia. Their fruit contained many winged seeds. The forsythia gave off a faint almond scent. The tiny flowers that produce milk sugar represented the white milk that gave him pleasure through the worst of his debilitating consumption. I added bits of baby’s breath—a cloud panicle of tiny white flowers—to refresh his tainted lungs. The flowers formed a small bridge, like hands touching. I picked up a few loose stones and slipped them into my pocket. Then I placed the incense in the circular holder, laying it flat. The sweet-smelling smoke enveloped his name. We were about to leave when the sun suddenly erupted, brightening everything. Perhaps the baby’s breath had found its mark and with refreshed lung Dazai had blown away the clouds that had blocked the sun.

—I think he’s happy, I said. Ace and Dice nodded in agreement.

Our final destination was the cemetery at Jigen-ji. As we approached the grave of Akutagawa, I recalled my dream and wondered how it would color my emotions. The dead regard us with curiosity. Ash, bits of bone, a handful of sand, the quiescence of organic material, waiting. We lay our flowers yet cannot sleep. We are wooed, then mocked, plagued like Amfortas, King of the Grail Knights, by a wound refusing to heal.

It was very cold and once again the sky grew dark. I felt strangely detached, numb, yet visually connected. Drawn to contrasting shadows I took four photographs of the incense burner. Though they were all similar I was pleased with them, envisioning them as panels on a dressing screen. Four panels one season. I bowed and thanked Akutagawa as Ace and Dice hurried to the car. As I followed after them, the capricious sun returned. I passed an ancient cherry tree bound in frayed burlap. The cold light deepened the texture of the binding and I framed my last shot: a comic mask whose ghostly tears seemed to streak the burlap’s worn threads.

The following evening I mentally prepared to change hotels, already mourning my secluded repetitive routine. I had been encased in Hotel Okura’s cocoon with two miserable moths, not wishing to emerge though not hiding their faces. Sitting at the metal desk I wrote a list of my coming duties including meetings with my publisher and translator. Then I would meet with Yuki and assist her with her continuing efforts on behalf of schoolchildren orphaned by the aftereffects of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. I packed my small suitcase in a haze of nostalgia for the present stream I was just about to divert, a handful of days in a world of my own making, fragile as a temple constructed with wooden matchsticks.

Comic mask

I went into the closet and removed a futon mat and buckwheat pillow. I unrolled the mat on the floor and wrapped my comforter around me. I was watching what appeared to be the end of a kind of soap opera set in the eighteenth century. It was slow-moving without subtitles or an ounce of happiness. Yet I was content. The comforter was like a cloud. I drifted, transient, following the brush of a maiden as she painted a scene of such sadness on the sails of a small wooden boat that she herself wept. Her robe made a swishing sound as she wandered barefoot from room to room. She exited through sliding panels that opened onto a snow-covered bank. There was no ice on the river and the boat sailed on without her. Do not cast your boat on a river of tears, cried the tearing wind. Small hands are still, be still. She knelt then lay on her side, clutching a key, accepting the kindness of endless sleep. The sleeve of her robe was adorned with the outlines of a lucent branch of delicate plum blossoms whose dark centers were a spattering of minuscule droplets. I closed my eyes as if to join the maiden as the droplets rearranged themselves, forming a pattern resembling an elongated island on the rim of an undisturbed blankness.

In the morning Ace drove me to a more central hotel chosen by my publisher, near the Shibuya train station. I had a room in a modern tower on the eighteenth floor with a view of Mt. Fuji. The hotel had a small café that served coffee in porcelain cups, all the coffee I wanted. The day was filled with duties, the lively atmosphere an unexpectedly welcome change. Late that night I sat before the window and looked at the great white-cloaked mountain that seemed to be watching over sleeping Japan.

In the morning I took the bullet train at Tokyo Station to Sendai where Yuki was waiting. Behind her smile I could see so many other things, a catastrophic sadness. I had assisted her from afar and now we would turn over the fruits of new efforts to the selfless guardians of the unfortunate children who suffered infinite loss, their family, their homes, and nature as they had known and trusted. Yuki spent time talking with the children’s teachers. Before we left they presented us with a precious gift of a Senbazuru, a thousand paper cranes held together by string. Many small fingers worked diligently to present us with the ultimate sign of good health and good wishes.

Afterwards we visited the once bustling fisherman’s port of Yuriage. The powerful tsunami, over one hundred feet high, had swept away nearly a thousand homes and all but a few battered ships. The rice fields, now unyielding, were covered with close to a million fish carcasses, a rotting stench that hung in the air for months. It was bitter cold and Yuki and I stood without words. I was prepared to see terrible damage but not for what I didn’t see. There was a small Buddha in the snow near the water and a lone shrine overlooking what had once been a thriving community. We walked up the steps leading to the shrine, a humble slate monolith. It was so cold we could barely pray. Will you take a picture? she said. I looked down at the bleak panorama and shook my head. How could I take a picture of nothing?

Yuki gave me a package and we said our farewells. I boarded the bullet train back to Tokyo. When I reached the station I found Ace and Dice waiting for me.

—I thought we said good-bye.

—We could not abandon you.

—Shall we go back to Mifune’s?

—Yes, let’s go. The sake is surely waiting.

Ace nodded and smiled. Time for sake, our last evening was drenched in it.

—What a nice cup and tokkuri, I noted. They were cerulean green with a small red stamp.

—That is the official sign of Kurosawa, said Dice.

Ace pulled on his beard, deep in thought. I roamed about the restaurant, admiring Kurosawa’s bold and colorful renderings of the warriors of Ran. As we happily made our way back to his car he produced the tokkuri and cup from his worn leather sack.

—Friendship makes thieves of us all, I said.

Dice was going to translate but Ace stopped him with his hand.

—I understand, he said solemnly.

—I will miss you both, I said.

That night I set the cup and tokkuri on the table next to the bed. It still contained drops of sake that I did not rinse out.

I awoke with a mild hangover. I got a cold shower and made my way through a labyrinth of escalators that led me nowhere. What I really wanted was coffee. I searched and found an express coffee shop—nine hundred yen for coffee and miniature croissants. Sitting at the next table facing mine was a man in his thirties dressed in a suit, white shirt, and tie, working on his laptop. I noted a subtle stripe in his suit that was understated yet defiantly different. He had a demeanor above the average businessman’s. He proceeded to change laptops, poured himself a coffee, then continued his work. I was touched by the serene yet complex concentration he manifested, the furrows of light on his smooth brow. He was handsome, in a certain way like a young Mishima, hinting at decorum, silent infidelities, and moral devotion. I watched the people passing. Time too was passing. I had thought to take a train to Kyoto for the day but preferred drinking coffee across from the quiet stranger.

In the end I did not go to Kyoto. I took one last walk, wondering what would happen if I bumped into Murakami on the street. But in truth I didn’t feel Murakami at all in Tokyo, and I hadn’t looked for the Miyawaki place, though its district was only a few miles away. So possessed with the dead I skipped contact with the fictional.

Murakami is not here anyway, I thought. He is most likely somewhere else, sealed in a space capsule in the center of a field of lavender, laboring over words.

That night I dined alone, an elegant meal of steaming abalone, green-tea soba noodles, and warm tea. I opened a gift from Yuki. It was a coral-colored box wrapped in heavy paper the color of sea foam. Inside the pale tissue were loops of soba from the Nagano prefecture. They lay in the oblong box like several strings of pearls. Lastly, I focused on my pictures. I spread them across the bed. Most of them went into a souvenir pile, but those of the incense burner at the grave of Akutagawa had merit; I would not go home empty-handed. I got up for a moment and stood by the window, looking down at the lights of Shibuya and across to Mt. Fuji. Then I opened a small jar of sake.

—I salute you, Akutagawa, I salute you, Dazai, I said, draining my cup.

—Don’t waste your time on us, they seemed to say, we are only bums.

I refilled the small cup and drank.

—All writers are bums, I murmured. May I be counted among you one day.