Tempest Air Demons

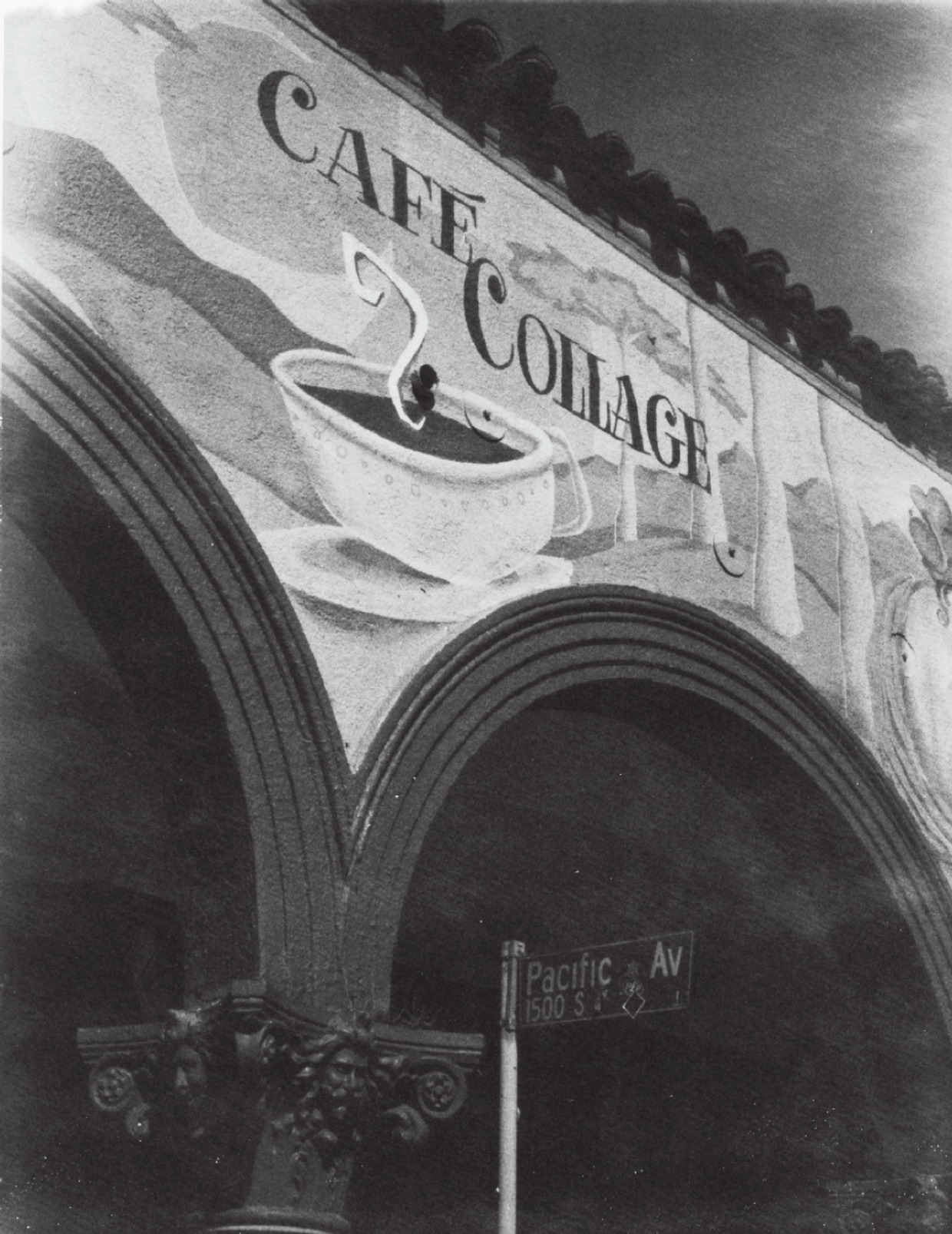

I TRAVELED HOME backwards through Los Angeles, stopping for a few days at Venice Beach, which is close to the airport. I sat on the rocks and stared at the sea, listening to crisscrossing music, discordant reggae with its revolutionary sense of harmonics drifting from various boom boxes. I ate fish tacos and drank coffee at the Café Collage, a block west from the Venice boardwalk. I never bothered to change my clothes. I rolled up my pant legs and walked in the water. It was cold but the salt felt good on my skin. I couldn’t bring myself to open my suitcase or computer. I lived out of a black cotton sack. I slept to the sound of the waves and spent a lot of time reading discarded newspapers.

After a last coffee at the Collage I headed for the airport, where I discovered my bags had been left at the hotel. I boarded the plane with nothing but my passport, white pen, toothbrush, traveler tube of Weleda salt toothpaste, and midsize Moleskine. I had no books to read and there was no in-flight entertainment for the five-hour flight. I immediately felt trapped. I flipped through the airline magazine featuring the top-ten skiing resorts in the country, then occupied myself with circling the names of all the places I’d been on the double-spread map of Europe and Scandinavia.

There were about thirteen hundred yen and four photographs inside the inner flap of the Moleskine. I laid the pictures out on the tray table: an image of my daughter, Jesse, in front of Café Hugo in Place des Vosges, two outtakes of the incense burner at the grave of Akutagawa, and one of the poet Sylvia Plath’s headstone in the snow. I tried to write something of Jesse but couldn’t, as her face echoed her father’s and the proud palace where the ghosts of our old life dwell. I slipped three of the pictures back into the pocket, then focused on Sylvia in the snow. It was not a good picture, the result of a kind of winter penitence. I decided to write of Sylvia. I wrote to give myself something to read.

It occurred to me that I was on a run of suicides. Akutagawa. Dazai. Plath. Death by water, barbiturates, and carbon monoxide poisoning; three fingers of oblivion, outplaying everything. Sylvia Plath took her life in the kitchen of her London flat on February 11, 1963. She was thirty years old. It was one of the coldest winters on record in England. It had been snowing since Boxing Day and the snow was piled high in the gutters. The River Thames was frozen and the sheep were starving on the fells. Her husband, the poet Ted Hughes, had left her. Their small children were safely tucked in their beds. Sylvia placed her head in the oven. One can only shudder at the existence of such overriding desolation. The timer ticking down. A few moments left, still a possibility to live, to turn off the gas. I wondered what passed through her mind in those moments: her children, the embryo of a poem, her philandering husband buttering toast with another woman. I wondered what happened to the oven. Perhaps the next tenant got an impeccably clean range, a massive reliquary for a poet’s last reflection and a strand of light brown hair caught on a metal hinge.

The plane seemed insufferably hot, yet other passengers were asking for blankets. I felt the inklings of a dull but oppressive headache. I closed my eyes and searched for a stored image of my copy of Ariel, given to me when I was twenty. Ariel became the book of my life then, drawing me to a poet with hair worthy of a Breck commercial and the incisive observational powers of a female surgeon cutting out her own heart. With little effort I visualized my Ariel perfectly. Slim, with faded black cloth, that I opened in my mind, noting my youthful signature on the cream endpaper. I turned the pages, revisiting the shape of each poem.

As I fixed on the first lines, impish forces projected multiple images of a white envelope, flickering at the corners of my eyes, thwarting my efforts to read them.

This agitating visitation produced a pang, for I knew the envelope well. It had once held a handful of images I had taken of the grave of the poet in the autumnal light of northern Britain. I had traveled from London to Leeds, through Brontë country to Hebden Bridge to the ancient Yorkshire village of Heptonstall to take them. I brought no flowers; I was singularly driven to get my shot.

I had only one pack of Polaroid film with me but I had no need of more. The light was exquisite and I shot with absolute assurance, seven to be exact. All were good, but five were perfect. I was so pleased that I asked a lone visitor, an affable Irishman, to take my picture in the grass beside her grave. I looked old in the photograph, but it contained the same scintillating light so I was content. In truth I felt an elation I hadn’t experienced in quite a while—that of easily accomplishing a challenging goal. Yet I offered a mere preoccupied prayer and did not leave my pen in a bucket by her headstone, as countless others had. I only had my favorite pen, a small white Montblanc, and did not want to part with it. I somehow felt exempt from this ritual, a contrariness I thought she would understand but that I would regret.

On the long drive to the train station I looked at the photographs, then slipped them into an envelope. In the hours to come I looked at them several times. Then some days later in my travels the envelope and its contents disappeared. Heartsick, I went over my every move but never found them. They simply vanished. I mourned the loss, magnified by the memory of the joy I’d felt in the taking of them in a strangely joyless time.

In early February I again found myself in London. I took a train to Leeds, where I had arranged for a driver to take me back to Heptonstall. This time I brought a lot of film and had cleaned my 250 Land Camera and painstakingly straightened the interior of the semi-collapsed bellows. We drove up a winding hill and the driver parked in front of the moody ruins of Saint Thomas à Becket Churchyard. I walked to the west of the ruins to an adjacent field across Back Lane and quickly found her grave.

—I have come back, Sylvia, I whispered, as if she’d been waiting.

I hadn’t factored in all the snow. It reflected the chalk sky already infused with murky smears. It would prove difficult for my simple camera, too much, then too little, available light. After half an hour my fingers were getting frostbitten and the wind was coming up, yet I stubbornly kept taking pictures. I hoped the sun would return and I irrationally shot, using all of my film. None of the pictures were good. I was numb with cold but couldn’t bear to leave. It was such a desolate place in winter, so lonely. Why had her husband buried her here? I wondered. Why not New England by the sea, where she was born, where salt winds could spiral over the name PLATH etched in her native stone? I had an uncontrollable urge to urinate and imagined spilling a small stream, some part of me wanting her to feel that proximate human warmth.

Life, Sylvia. Life.

The bucket of pens was gone, perhaps retired for winter. I went through my pockets, extracting a small spiral notebook, a purple ribbon, and a cotton lisle sock with a bee embroidered near the top. I tied the ribbon around them and tucked them by her headstone. The last of the light faded as I trudged back to the heavy gate. It was only as I approached the car that the sun appeared and now with a vengeance. I turned just as a voice whispered:

—Don’t look back, don’t look back.

It was as if Lot’s wife, a pillar of salt, had toppled on the snow-covered ground and spread a lengthening heat melting all in its path. The warmth drew life, drawing out tufts of green and a slow procession of souls. Sylvia, in a cream-colored sweater and straight skirt, shading her eyes from the mischievous sun, walking on into the great return.

In early spring I visited Sylvia Plath’s grave for a third time, with my sister Linda. She longed to journey through Brontë country and so we did together. We traced the steps of the Brontë sisters and then traveled up the hill to trace mine. Linda delighted in the overgrown fields, the wildflowers, and the Gothic ruins. I sat quietly by the grave, conscious of a rare, suspended peace.

Spanish pilgrims travel on Camino de Santiago from monastery to monastery, collecting small medals to attach to their rosary as proof of their steps. I have stacks of Polaroids, each marking my own, that I sometimes spread out like tarots or baseball cards of an imagined celestial team. There is now one of Sylvia in spring. It is very nice, but lacking the shimmering quality of the lost ones. Nothing can be truly replicated. Not a love, not a jewel, not a single line.

Grave of Sylvia Plath, winter

I awoke to the sound of church bells ringing from the tower of Our Lady of Pompeii. It was 8 a.m. At last some semblances of synchronicity. I was weary of having my morning coffee at night. Coming home through Los Angeles had twisted some inner mechanism, and like an errant cuckoo clock I was operating on time interrupted by itself. My reentry had spun out strangely. Victim of my own comedy of errors, my suitcase and computer stranded in Venice Beach, and then despite the fact I had only a black cotton sack to be mindful of, I left my notebook on the plane. Once home, in disbelief I dumped the meager contents of my sack onto my bed, examining them over and over as if the notebook would appear in the negative recesses between the other items. Cairo sat on the empty sack. I looked helplessly around my room. I have enough stuff, I told myself.

Days later an unmarked brown envelope appeared at my mail drop; I could see the outline of the black Moleskine. Grateful but perplexed I finally opened it. There was no note, no one to thank but the demon air. I extracted the photograph of Sylvia in the snow and examined it carefully. My penance for barely being present in the world, not the world between the pages of books, or the layered atmosphere of my own mind, but the world that is real to others. I then slipped it between the pages of Ariel. I sat reading the title poem, pausing at the lines And I / Am the arrow, a mantra that once emboldened a rather awkward but determined young girl. I had almost forgotten. Robert Lowell tells us in the introduction that Ariel does not refer to the chameleonlike sprite in Shakespeare’s Tempest, but to her favorite horse. But perhaps the horse was named after the Tempest spirit. Ariel angel alters lion of God. All are good, but it is the horse that flies over the finish line with Sylvia’s arms wrapped around his neck.

There was also a fair copy of a poem called “New Foal” that I placed in the book some time ago. It describes the birth and arrival of a foal, reminiscent of Superman as a babe, encrusted in a dark pod and hurled into space toward Earth. The foal lands, teeters, is smoothed by God and man to become horse. The poet who wrote it is one with the dust, but the new foal he created is lively, continually born and reborn.

I was glad to be home, sleeping in my own bed, with my little television and all my books. I had only been gone a few weeks but it somehow felt stretched into months. It was about time I salvaged a bit of my routine. It was too early to go to ’Ino, so I read. Rather, I looked at the pictures in Nabokov’s Butterflies and read all the captions. Then I washed, put on clean versions of what I was already wearing, grabbed my notebook, and hurried downstairs, the cats trailing after me, finally recognizing my habits as their own.

March winds, both feet on the ground. The spell of jet lag broken, I was looking forward to sitting at my corner table and receiving my black coffee, brown toast, and olive oil without asking for it. There were twice as many pigeons than usual on Bedford Street, and a few daffodils had come up early. It didn’t register at first, but then I realized that the blood-orange awning with ’Ino across it was missing. The door was locked, but I saw Jason inside and I tapped on the window.

—I’m glad you came by. Let me make you one last coffee.

I was too stunned to speak. He was closing up shop and that was it. I looked at my corner. I saw myself sitting there on countless mornings through countless years.

—Can I sit down? I asked.

—Sure, go ahead.

I sat there all morning. A young girl who frequented the café was going by carrying a Polaroid camera identical to my own. I waved and went out to greet her.

—Hello, Claire, do you have a moment?

— Of course, she said.

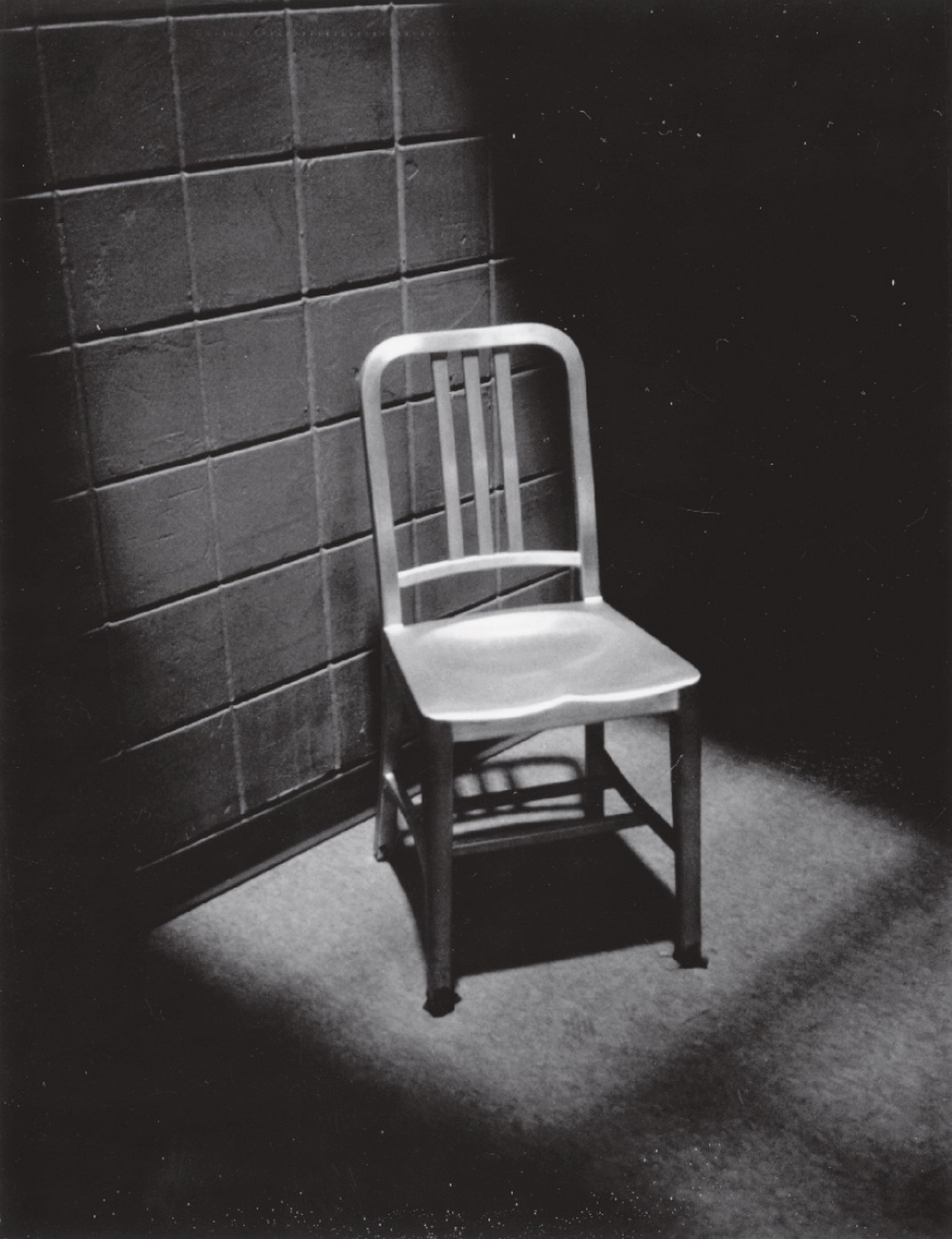

I asked her to take my picture. The first and last picture at my corner table in ’Ino. She was sad for me, having seen me through the window many times in passing. She took a few shots and laid one on the table—the picture of woebegone. I thanked her as she left. I sat there for a long time thinking of nothing, and then picked up my white pen. I wrote of the well and the face of Jean Reno. I wrote of the cowpoke and the crooked smile of my husband. I wrote of the bats of Austin, Texas, and the silver chairs in the interrogation room in Criminal Intent. I wrote till I was spent, the last words written in Café ’Ino.

Before we parted, Jason and I stood and looked around the small café together. I didn’t ask him why he was closing. I figured he had his reasons, and the answer wouldn’t make any difference anyway.

I said good-bye to my corner.

—What will happen to the tables and chairs? I asked.

—You mean your table and chair?

—Yeah, mostly.

—They’re yours, he said. I’ll bring them over later.

That evening Jason carried them from Bedford Street across Sixth Avenue, the same route I had taken for over a decade. My table and chair from the Café ’Ino. My portal to where.

I climbed the fourteen steps to my bedroom, turned off the light, and lay there awake. I was thinking about how New York City at night is like a stage set. I was thinking of how on a plane home from London I watched a pilot for a TV show I’d never heard of called Person of Interest and how two nights later there was a film crew on my street and they asked me to not pass while they were shooting and I spotted the main guy in Person of Interest being shot for a scene beneath the scaffolding about fifteen feet from the right of my door. I was thinking about how much I love this city.

I found the channel changer and watched the end of an episode of Doctor Who. The David Tennant configuration, the only Doctor Who for me.

—One may tolerate the demons for the sake of an angel, Madame Pompadour tells him before he transports into another dimension. I was thinking what a beautiful match they would have made. I was thinking of French time-traveling children with Scottish accents breaking the hearts of the future. Simultaneously, a blood-orange awning turned in my mind like a small twister. I wondered if it was possible to devise a new kind of thinking.

It was nearly dawn before I sank into sleep. I had another dream about the café in the desert. This time the cowpoke was standing at the door, gazing at the open plain. He reached over and lightly gripped my arm. I noticed that there was a crescent moon tattooed in the space between his thumb and forefinger. A writer’s hand.

—How is it that we stray away from one another, then always come back?

—Do we really come back to one another, I answered, or just come here and lazily collide?

He didn’t answer.

—There’s nothing lonelier than the land, he said.

—Why lonely?

—Because it’s so damn free.

And then he was gone. I walked over and stood where he had been standing and felt the warmth of his presence. The wind was picking up and unidentifiable bits of debris were circling in the air. Something was coming, I could feel it.

I stumbled out of bed, fully clothed. I was still thinking. Half asleep I slipped on my boots and dragged a carved Spanish chest from the back of the closet. It had the patina of a worn saddle, with a number of drawers filled with objects, some sacred and some whose origins were entirely forgotten. I found what I was looking for—a snapshot of an English greyhound with Specter, 1971 written on the back. It was between the pages of a worn copy of Hawk Moon by Sam Shepard with his inscription, If you’ve forgotten hunger your crazy. I went to the bathroom to wash. A slightly waterlogged copy of No Longer Human was on the floor beneath the sink. I rinsed off my face, grabbed my notebook, and headed for Café ’Ino. Halfway across Sixth Avenue, I remembered.

I began to spend more time at the Dante but at irregular hours. In the mornings I just got deli coffee and sat on my stoop. I reflected on how my mornings at Café ’Ino had not only prolonged but also afforded my malaise with a small amount of grandeur. Thank you, I said. I have lived in my own book. One I never planned to write, recording time backwards and forwards. I have watched the snow fall onto the sea and traced the steps of a traveler long gone. I have relived moments that were perfect in their certainty. Fred buttoning the khaki shirt he wore for his flying lessons. Doves returning to nest on our balcony. Our daughter, Jesse, standing before me stretching out her arms.

—Oh, Mama, sometimes I feel like a new tree.

We want things we cannot have. We seek to reclaim a certain moment, sound, sensation. I want to hear my mother’s voice. I want to see my children as children. Hands small, feet swift. Everything changes. Boy grown, father dead, daughter taller than me, weeping from a bad dream. Please stay forever, I say to the things I know. Don’t go. Don’t grow.