Genet’s grave, Larache Christian Cemetery

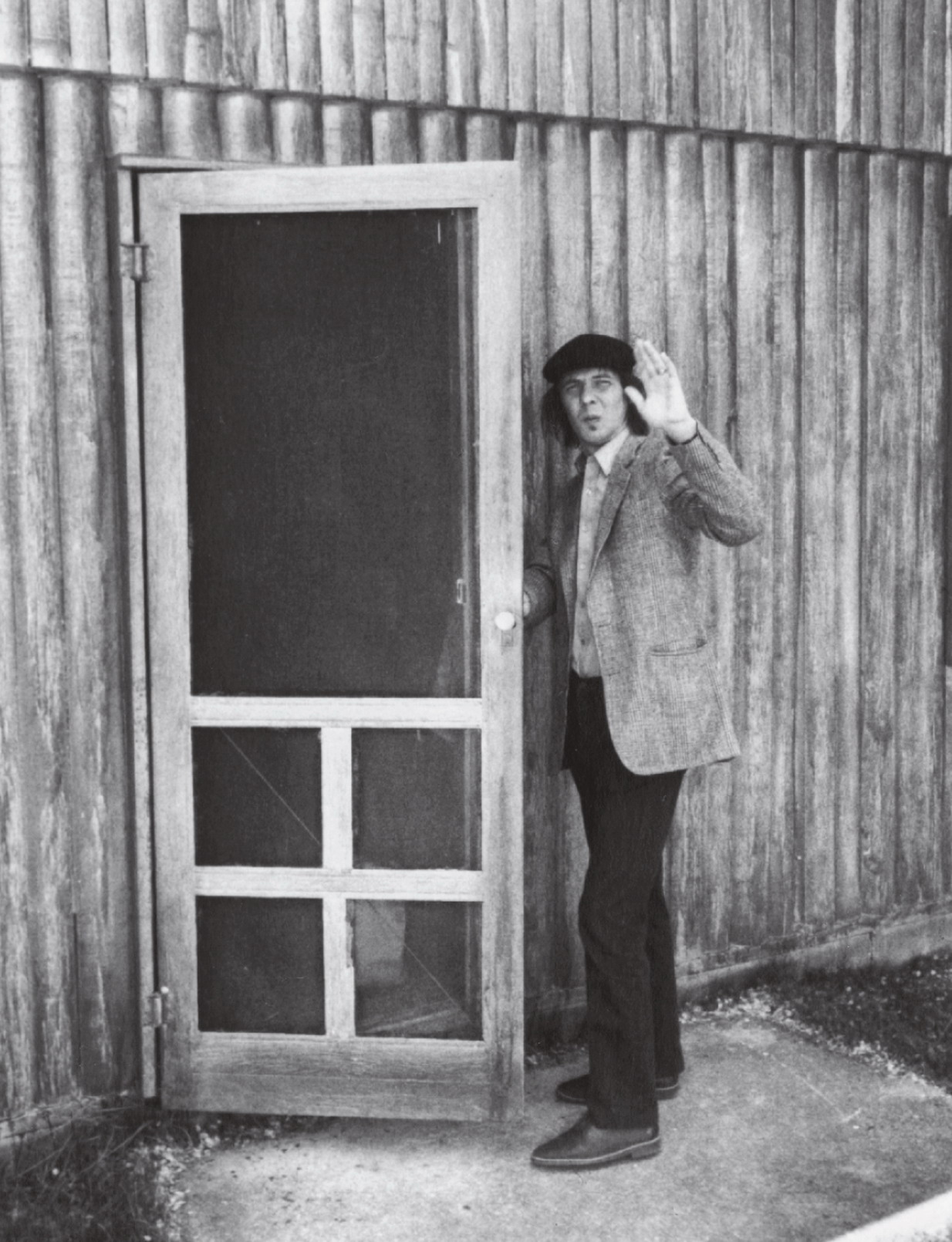

Father’s Day, Lake Ann, Michigan

Covered Ground

MEMORIAL DAY WAS fast approaching. I had a longing to see my little house, my Alamo, train or no train. The great storm destroyed the Broad Channel rail bridge, washing out more than fifteen hundred feet of track, completely flooding two stations on the A line, requiring massive repairs, signals, switches, and wiring. There was no point in being impatient. It remained a truly daunting task, like piecing together the shattered mandolin of Bill Monroe.

I called my friend Winch, the overseer of its slow renovation, to hitch a ride to Rockaway Beach. It was sunny though unseasonably cold, so I wore an old peacoat and my watch cap. Having time to kill, I got a large deli coffee and waited for him on my stoop. The sky was clear save for a few drifting clouds, and I followed them back to northern Michigan on another Memorial Day in Traverse City. Fred was flying, and our young son, Jackson, and I were walking along Lake Michigan. The beach was littered with hundreds of feathers. I laid down an Indian blanket and got out my pen and notebook.

—I am going to write, I told him. What will you do?

He surveyed the area with his eyes, fixing on the sky.

—I’m going to think, he said.

—Well, thinking is a lot like writing.

—Yes, he said, only in your head.

He was approaching his fourth birthday and I marveled at his observation. I wrote, Jackson reflected, and Fred flew, somehow all connected through the blood of concentration. We had a happy day, and when the sun began to recede I gathered up our things along with a few feathers and Jack ran on ahead, anticipating his father’s return.

Even now, his father dead for some twenty years, and Jackson a man anticipating the arrival of his own son, I can picture that afternoon. The strong waves of Lake Michigan lapping the shore littered with the feathers of molting gulls. Jackson’s little blue shoes, his quiet ways, the steam rising from my thermos of black coffee, and the gathering clouds that Fred would be eyeing from the cockpit window of a Piper Cherokee.

—Do you think he can see us? Jack asked.

—He always sees us, my boy, I answered.

Images have their way of dissolving and then abruptly returning, pulling along the joy and pain attached to them like tin cans rattling from the back of an old-fashioned wedding vehicle. A black dog on a strip of beach, Fred standing in the shadows of mangy palms flanking the entrance to Saint-Laurent Prison, the blue-and-yellow Gitane matchbox wrapped in his handkerchief, and Jackson racing ahead, searching for his father in the pale sky.

I slid into the pickup truck with Winch. We didn’t talk much, both of us lost in our own thoughts. There was little traffic and we made it in about forty minutes. We met with the four fellows who made up his crew. Hardworking men sensitive to their task. I noticed all my neighbors’ trees were dead. They were the closest I had to trees of my own. The great storm surges that flooded the streets had killed most of the vegetation. I inspected all that there was to see. The mildewed pasteboard walls forming small rooms had been gutted, opening onto a large room with the century-old vaulted ceiling intact, and rotted floors were being removed. I could feel progress and left with a bit of optimism. I sat on the makeshift step of what would be my refurbished porch and envisioned a yard with wildflowers. Anxious for some permanency, I guess I needed to be reminded how temporal permanency is.

I walked across the road toward the sea. A newly stationed shore patrol shooed me away from the beach area. They were dredging where the boardwalk had been. The sand-colored outpost that had briefly housed Zak’s café was under government renovation, repainted canary yellow and bright turquoise, expunging its Foreign Legion appeal. I could only hope the dramatically cheery colors would bleach out in the sun. I walked farther down to gain entrance onto the beach, got my feet wet, and then got some coffee to go from the sole surviving taco stand.

I asked if anyone had seen Zak.

—He made the coffee, they told me.

—Is he here? I asked.

—He’s somewhere around.

Clouds drifted overhead. Memorial clouds. Passenger jets were taking off from JFK. Winch finished his tasks and we got back into the pickup truck and headed back across the channel, past the airport, over the bridge, and into the city. My dungarees were still damp from skirting the sea, and bits of sand shook out onto the floor that had been caught in the rolled-up folds. When I finished the coffee I couldn’t part with the empty container. It occurred to me I could preserve the history of ’Ino, the lost boardwalk, and whatever came to mind in microscript upon the Styrofoam cup, like an engraver etching the Twenty-third Psalm on the head of a pin.

WHEN FRED DIED, we held his memorial in the Detroit Mariners’ Church where we were married. Every November Father Ingalls, who wed us, held a service in memory of the twenty-nine crewmembers who went down in Lake Superior on the Edmund Fitzgerald, ending with ringing the heavy brotherhood bell twenty-nine times. Fred was deeply moved by this ritual, and as his memorial coincided with theirs, the father allowed the flowers and the model of the ship to be left on the stage. Father Ingalls presided over the service and wore an anchor around his neck in lieu of a cross.

The evening of the service, my brother, Todd, came upstairs for me, but I was still in bed.

—I can’t do it, I told him.

—You have to, he said adamantly, and he shook me from my torpor, helped me to dress, and drove me to the church. I thought about what I would say, and the song “What a Wonderful World” came on the radio. Whenever we heard it Fred would say, Trisha, it’s your song. Why does it have to be my song? I’d protest. I don’t even like Louis Armstrong. But he would insist the song was mine. It felt like a sign from Fred, so I decided to sing “Wonderful World” a cappella at the service. As I sang I felt the simplistic beauty of the song, but I still didn’t understand why he connected it with me, a question I had waited too long to ask. Now it’s your song, I said, addressing a lingering void. The world seemed drained of wonder. I did not write poems in a fever. I did not see the spirit of Fred before me or feel the spinning trajectory of his journey.

My brother stayed with me through the days that followed. He promised the children he would be there for them always and would return after the holidays. But exactly a month later he had a massive stroke while wrapping Christmas presents for his daughter. The sudden death of Todd, so soon after Fred’s passing, seemed unbearable. The shock left me numb. I spent hours sitting in Fred’s favorite chair, dreading my own imagination. I rose and performed small tasks with the mute concentration of one imprisoned in ice.

Eventually I left Michigan and returned to New York with our children. One afternoon while crossing the street I noticed I was crying. But I could not identify the source of my tears. I felt a heat containing the colors of autumn. The dark stone in my heart pulsed quietly, igniting like a coal in a hearth. Who is in my heart? I wondered.

I soon recognized Todd’s humorous spirit, and as I continued my walk I slowly reclaimed an aspect of him that was also myself—a natural optimism. And slowly the leaves of my life turned, and I saw myself pointing out simple things to Fred, skies of blue, clouds of white, hoping to penetrate the veil of a congenital sorrow. I saw his pale eyes looking intently into mine, trying to trap my walleye in his unfaltering gaze. That alone took up several pages that filled me with such painful longing that I fed them into the fire in my heart, like Gogol burning page by page the manuscript of Dead Souls Two. I burned them all, one by one; they did not form ash, did not go cold, but radiated the warmth of human compassion.