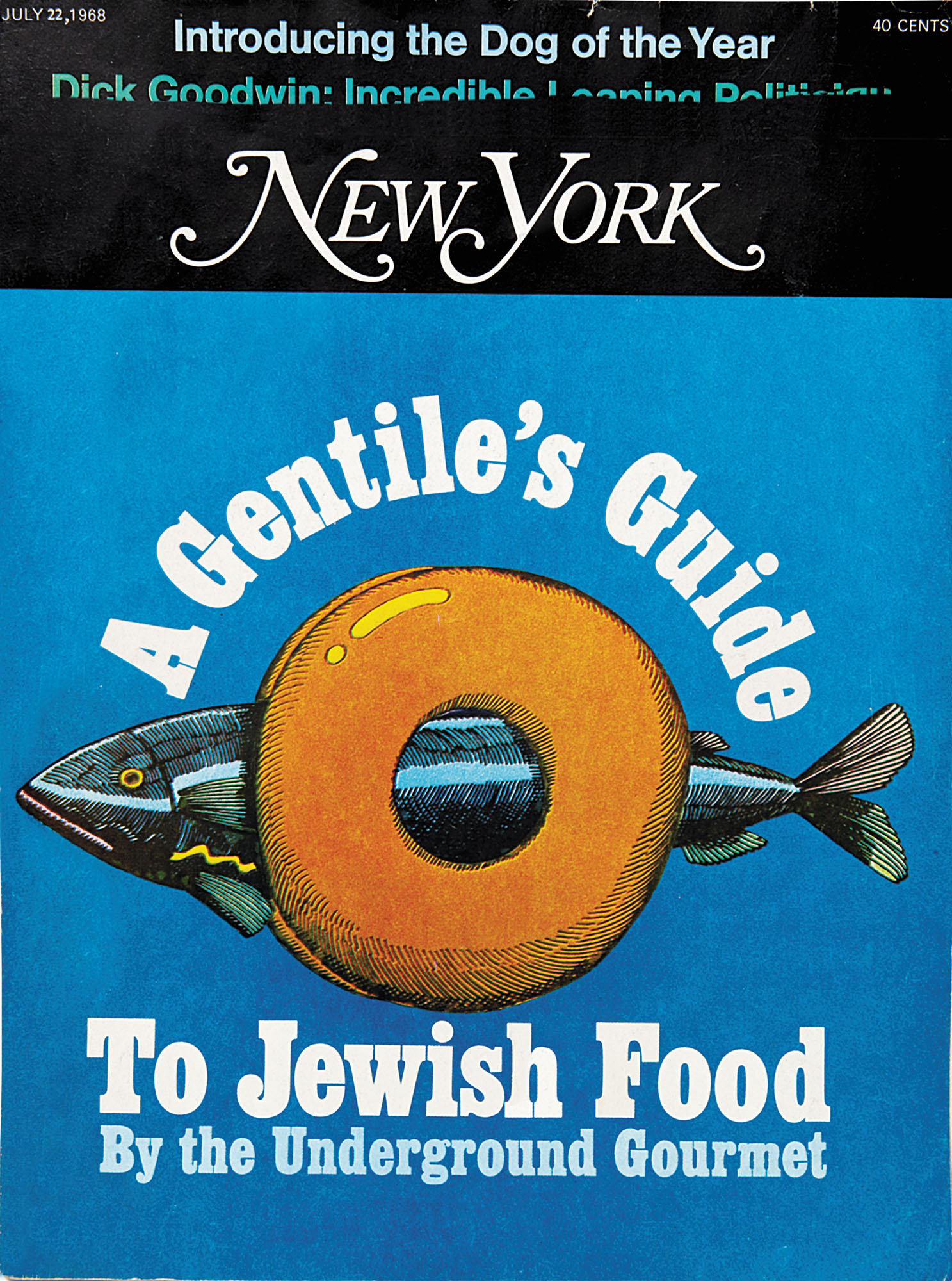

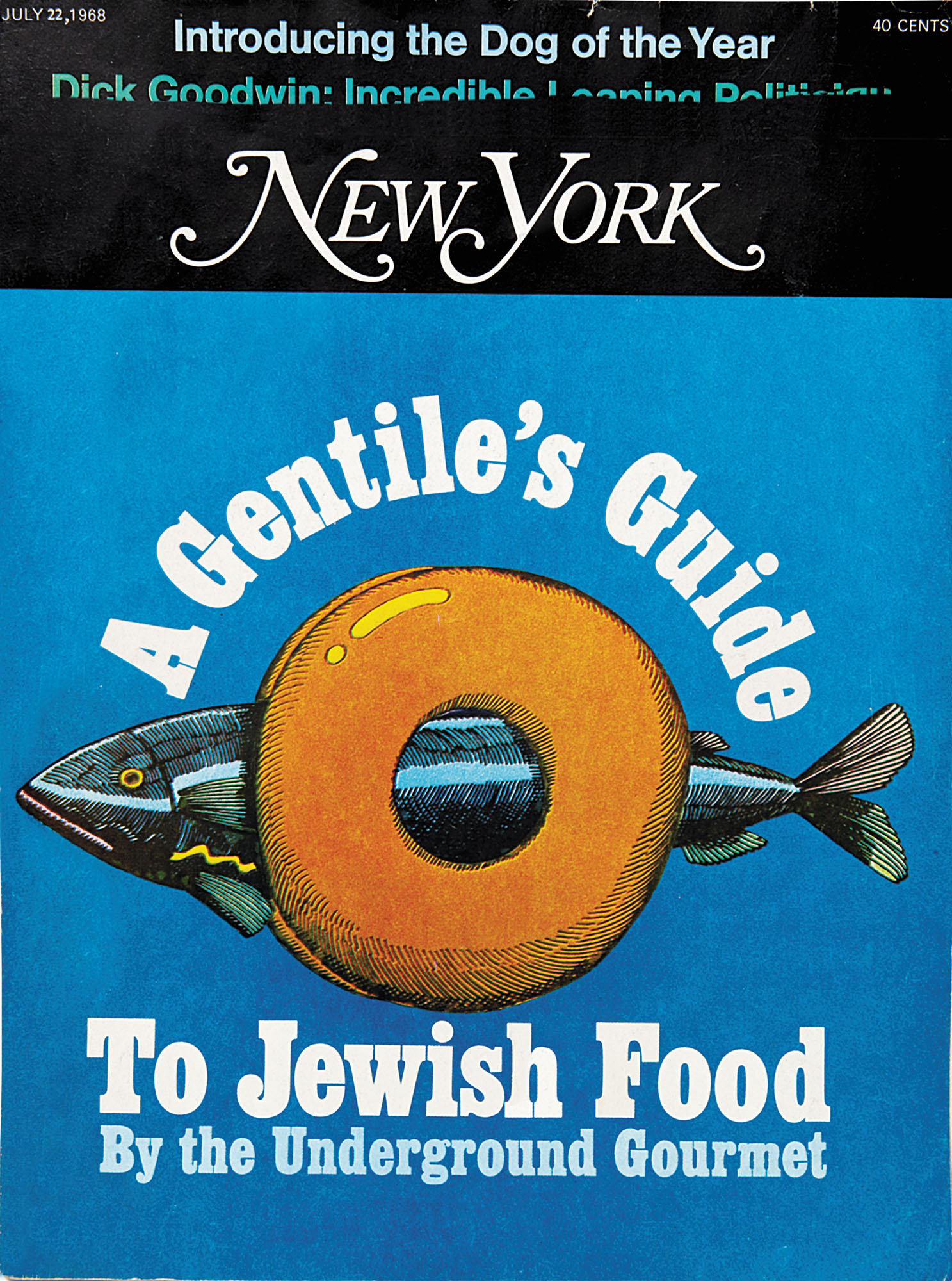

The magazine started out taking whitefish seriously.

The Underground Gourmet’s first cover story planted the flag for vernacular, humble deliciousness.

“IT REALLY WAS A SHIFT in consciousness,” recalls Milton Glaser, New York’s co-founder and creator of the “Underground Gourmet” column. “Jerome Snyder, who was the art director of Scientific American and a wonderful guy—we were always one-upping each other on who knew the cheapest and best restaurant, and one day I realized that was never reported anywhere, because these little dinky joints didn’t buy advertising. We were saying, Hey, there’s gold here, and we’re not getting it. It was such a reward for people.” ¶ That “shift in consciousness” was true not only in journalism but in the culture at large. Fifty years ago, dining out took place in two kinds of restaurants: white-tablecloth French places that were completely bound to tradition, and ethnic dives that had great food and zero amenities. New York’s first critics—Gael Greene with her focus on sensual pleasure, and Glaser and Snyder on the kung-pao-and-knishes beat—saw that giant gulf beginning to close, and grasped that New York was at the leading edge of a revolution in food. Within a few years, the hidebound French were being challenged by innovators: newly sophisticated Italian, then nouvelle cuisine, then Japanese and fusion and New American. The little neighborhood places started to get more and more attention, and their cooking began to influence the uptown chefs. Getting into a hot new restaurant became like chasing tickets to a hot Broadway show. In 1980, Greene coined a new word, foodie, to describe these obsessive restaurant-chasers, and it eventually became such easy and widespread shorthand that New York’s copy desk banned its use for a while. ¶ The explosion in restaurant culture led to a parallel boom in home cooking and food awareness. The pursuit of the fresh and local and seasonal, helped along by the creation of the Greenmarket in 1976, redefined not only our way of eating but the neighborhood around Union Square. Chefs became celebrities and began to mine the world’s food cultures for ideas. They discovered that, owing mostly to thrift, those little ethnic restaurants were cooking every part of the animal and not just the best cuts; the nose-to-tail movement was born. They also realized that humble dishes, like the all-American burger, could be made luxurious with custom meat blends and maybe a little foie gras in the middle. Food culture became a youth culture, one where packs of hungry 24-year-olds line up for the best ramen bar or food truck or Cronut bakery and then post a picture of every meal on Instagram. By 2017, young-skewing neighborhoods like Ridgewood and Greenpoint were blanketed with low-end-high-end places, where a dressy pizza or a superior burger and fries, instead of pâté or pike quenelles, constituted a major dining experience. The Underground Gourmet had, in a sense, eaten the whole world. Or, as Glaser puts it, “Good food, cheap. Well, what else do you want?”

The magazine started out taking whitefish seriously.

The Underground Gourmet’s first cover story planted the flag for vernacular, humble deliciousness.

This photograph was even funnier if you’d seen the commercials.

In the mid-1970s, a series of ubiquitous TV ads featured century-old Soviet Georgians who attributed their long lives to eating lots of yogurt. For our tasting, we recruited our own.

PHOTOGRAPH BY CARL FISCHER