The Problem with Videogames

I have a problem with videogames.1

Plenty of people seem to have problems with videogames these days. Newscasters are fond of reporting that videogames are dangerous to children, either because they teach children how to steal cars and kill cops or because they actually connect children electronically to the game-playing predators who are waiting to snatch them away. Religious leaders have wasted no time condemning videogames as a trap for children’s souls, and armchair psychologists accuse them of turning kids into antisocial hermits.

People condemn videogames because videogames are pervasive in popular culture. They’re on our computers and our cell phones, in our homes and purses and pockets. Even if you yourself don’t play games, you have a hard time escaping their marketing. When the television isn’t telling you to be afraid of videogames, it’s telling you to buy them, and to drink World of Warcraft–flavored Mountain Dew while you play.

These are some problems people have with videogames. What’s my problem with videogames?

As a queer transgendered woman in 2012, in a culture pervaded by videogames—a culture in which, typing on my computer, I am seconds away from a digital game, even if I have not taken the time to buy or install a single game on my computer—I have to strain to find any game that’s about a queer woman, to find any game that resembles my own experience.

This is in spite of the fact that videogames in America and elsewhere are an industry and an institution. I’ve already brought up World of Warcraft, a game about performing repetitive tasks until numbers increase. So, now that we’re in the land of numbers, here are some numbers. The ESA—that’s the Entertainment Software Association, who spend half their time assuring the population that videogames aren’t worth being mad at, and the other half pursuing litigation against anyone who distributes games that their shareholders have long since stopped distributing or profiting from—claims that, as of 2009, 68 percent of American households play digital games.2 In 2008 alone, people bought 269,100,000 games (the ESA word is units.)3

So digital games, by the numbers, are here, and they take up a lot of space. And almost none of these games are about me, or anyone like me.

What are videogames about?

Mostly, videogames are about men shooting men in the face. Sometimes they are about women shooting men in the face. Sometimes the men who are shot in the face are orcs, zombies, or monsters. Most of the other games the ESA is talking about when it mentions “units” are abstract games: the story of a blue square who waits for a player to place him in a line with two other blue squares, so he can disappear forever. The few commercial games that involve a woman protagonist in a role other than slaughterer put her in a role of servitude: waiting tables at a diner (or a dress shop, a pet shop, a wedding party). This is not to say that games about head shots are without value, but if one looked solely at videogames, one would think the whole of human experience is shooting men and taking their dinner orders. Surely an artistic form that has as much weight in popular culture as the videogame does now has more to offer than such a narrow view of what it is to be human.

And yes, from here on out I’ll be talking about videogames as an art form. What I mean by this is that games, digital and otherwise, transmit ideas and culture. This is something they share with poems, novels, music albums, films, sculptures, and paintings. A painting conveys what it’s like to experience the subject as an image; a game conveys what it’s like to experience the subject as a system of rules. If videogames are compared unfavorably to other art forms such as novels and songs and films—and they are compared unfavorably with these forms, or else this paragraph defending videogames as art wouldn’t be necessary—it is likely a result of how limited a perspective videogames have offered up to this point. Imagine a world in which art forms are assigned value by the number of dykes that populate them. This is the world I inhabit; this is the value games have for me. And why not? The number of stories from marginalized cultures—from people who are othered by the mainstream—that a form contains tells us something about that form’s maturity. If a form has attracted so many authors, so many voices, that several of them come from experiences outside the social norm and bring those experiences and voices to bear when working in that form, can’t that form be said to have reached cultural maturity?

It should go without saying that novels and films have plenty of dykes in them, as do the media of writing and filmmaking. American comics have been around since 1896—that’s over one hundred years—yet comics are still involved in a debate, as videogames are, about their cultural and artistic value. But I can think of many comics about queer women. More important, I can think of plenty of queer women who make comics: to name a few, Diane DiMassa, Alison Bechdel, Jennifer Camper, Kris Dresen, and Colleen Coover, in order of how disappointed I was when they came out in defense of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival.4 And those are just print comics, in a world where the majority of comics are published on the Internet.

In Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For, Mo (a dyke to watch out for) explains a metric she uses to decide whether she’ll watch a movie. This criteria has become known as the Bechdel Test: the movie has to (1) contain at least two women who (2) talk to each other about (3) something other than a man. So why do videogames fail my variant of the Bechdel Test? Why are there no dykes in videogames?

I know at least one of you has been itching, for several pages, to point out games like Fear Effect 2: Retro Helix and Mass Effect, both of which include scenes in which women smooch women, both on and off camera. In Fear Effect 2, women make out for the benefit of the male audience the game’s creators expect to buy the game. (The first scene, in fact, is of the protagonist stripping as seen through a hidden camera, which tells us something about her relationship to the player.) And the lady-sex in Mass Effect is just one of many branches on a tree of awkward dialogue, offering nothing resembling the actual lust, desire, and flirtation that women feel for each other. But, aesthetic failures aside, the most important distinction here is that these are stories about queer women that are generally written by white, college-educated men. These are not cases of queer women presenting their own experiences.

Why are digital games so sparse in the dykes making art department? Why are the experiences that games present, the stories they tell, the voices in which they speak, so limited?

The limitations of games aren’t just thematic. When I criticize games for being mostly about shooting people in the head, that’s a design criticism as well. Most games are copies of existing successful games. They play like other games, resemble their contemporaries in shape and structure, have the same buttons that interact with the world in the same way (mouse to aim, left click to shoot), and have the same shortcomings. If there’s a vast pool of experiences that contemporary videogames are failing to tap, then there’s just as large a pool of aesthetic and design possibilities that are being ignored. I don’t believe these are separate issues, either. To tell different stories, we need different ways of interacting with games. Why are games so similar in terms of both content and design?

The problem with videogames is that they’re created by a small, insular group of people. Digital games largely come from within a single culture. When computers were first installed in college campuses and laboratories, only engineers had the access to the machines, the comparative leisure time, and the technical knowledge to teach those computers to play games. It is not surprising that the games they made looked like their own experiences: physics simulations, space adventures drawn from the science fiction they enjoyed, the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop role-playing games they played with their friends. As computers made their way out of labs and into homes, the games that programmers were hacking together became a salable product—and salespeople showed up to profit off of them. And so as businessmen and marketers guided videogames into becoming a billion-dollar industry, publishers installed themselves as the gatekeepers of game creation.

Commercial games have become expensive: according to a presentation at the High Performance Graphics 2009 conference, Gears of War 2—an industry leader in the “men shooting things” genre—had a “development budget” of 12 million dollars.5 (“Development” refers just to the cost of creating the game—it doesn’t include all the bucks that were spent marketing, manufacturing, and shipping the game.) If the game cost that much to produce, you can imagine what it would have to earn in sales in order to make any money. Hint: more than 12 million dollars. With that much money at stake, publishers and shareholders are not going to permit a game that is experimental either in terms of its content or in terms of its design. The publisher will do the minimum amount it can get away with in order to differentiate its game from all other games that follow its previously established model and that are being sold to its previously established audience.

Now we have a dangerous cycle: publishers permit only games that follow a previously established model to be marketed to previously established audiences, and only to those audiences. The audiences in question are mostly young adults, and mostly male. And it’s these dudes, already entrenched in the existing culture of games, who are eventually driven to enter the videogame industry and to take part in the creation of games. The population who creates games becomes more and more insular and homogeneous: it’s the same small group of people who are creating the same games for themselves.

Videogames as they’re commonly conceived today both come from and contain exactly one perspective. It should be terrifying that an entire art form can be dominated by a single perspective, that a small and privileged group has a monopoly on the creation of art. Before the adoption of the printing press, the church was responsible for the creation of books, and the books that monks hand-lettered in Latin in monasteries were largely the Bible or books that agreed with the Bible. Not to knock the Bible, but that a single institution can hold power over what works are allowed to exist within any art form should demonstrate the power that institution has over that art form, and therefore over that culture. And so the printing press, which allowed people to print their own versions of the Bible in their own languages—and eventually to print books that had nothing to do with the Bible—had a role to play in the decentralization of religious authority in Europe.

The printing press is a piece of technology. If digital games, a form that is often (and not entirely correctly) described as being “technology driven,” can be compared to books, where then is the printing press for videogames?

What Videogames Need

There’s a videogame about a dyke who convinces her girlfriend to stop drinking. Mainstream gamer culture by and large does not know about this game. I know about this game because I made it.

I created Calamity Annie in 2008. I made it by myself: I wrote the dialogue, composed the music, designed the rules, scripted the game, and drew all the characters. It was made in a couple of months. The development costs were the cost of the food that went into my belly. I made the game in a program called Game Maker, which, at the time, cost fifteen dollars.

I am nowhere close to the only person who has used Game Maker, nowhere close to the only person who makes digital games outside of the games industry’s publisher model. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of such creators. A few of them have achieved some mainstream recognition, like Jonathan Blow and Jason Rohrer, who was profiled in Esquire magazine. But these rich white dudes were professional programmers before they came to videogames, and so they don’t represent the new dynamic that I’m excited about: hobbyists and non-programmers making their first games. There are lots of tools that allow people to make and distribute games without ever having written a line of code and without having to pass through publishers’ gates. In years to come, there will be a lot more tools. I hope that there will also be a lot more people.

I once heard the criticism that the phrase “what videogames need” can usually be more honestly rephrased as “what I want from videogames.” In that case, what I want from videogames is a plurality of voices. I want games to come from a wider set of experiences and present a wider range of perspectives. I can imagine—you are invited to imagine with me—a world in which digital games are not manufactured by publishers for the same small audience, but one in which games are authored by you and me for the benefit of our peers.

This is something the videogame industry, by its nature, cannot give us. I like to think about zines—self-published, self-distributed magazines and books. Send me a dollar and a self-addressed envelope; I’ll send you a stapled book of some stories from my life, or some pictures I took of out-of-the-way nooks of my city, or researched accounts of historical murders, or some jokes about sea life. (What does the merman’s waiter bring? He brings the MERMANATEE.6) I like the idea of games as zines: as transmissions of ideas and culture from person to person, as personal artifacts instead of impersonal creations by teams of forty-five artists and fifteen programmers, in the case of Gears of War 2.

The Internet in particular has made self-publishing and distributing games both possible and easy. Authors are able not only to put their works online, but to find audiences for them. Publishers want to be gatekeepers to the creation of videogames, but the Internet has opened those gates.

Currently, the only real barrier to game creation is the technical ability to design and create games—and that, too, is a problem that is in the process of being solved.

Digital game creation was once limited to those who knew how to speak with computers: engineers and programmers, people who could code. In the games industry of today, coders are an inescapable fixture of the hierarchy of production, since games that we play with machines need creators capable of negotiating with machines. Game creation is daunting for someone who doesn’t code professionally. But more and more game-making tools are being designed with people who aren’t professional coders in mind. (I describe several of these tools, and what each is good for, in the appendix.) It’s now possible for people with no programming experience—hobbyists, independent game designers, zinesters—to make their own games and to distribute them online.

What I want from videogames is for creation to be open to everyone, not just to publishers and programmers. I want games to be personal and meaningful, not just pulp for an established audience. I want game creation to be decentralized. I want open access to the creative act for everyone. I want games as zines.

It’s a tall order, maybe, but the ladder’s being built as you read these words.

Is What You Want Really What Games Need?

Why transform videogames, though? What do I get out of it? What, for that matter, do videogames get out of it?

In 2005, movie critic Roger Ebert infamously remarked that he does not think games can ever be considered as art. (By whom? By him, apparently.) He argues, mostly by assertion, that he doesn’t feel game designers can exercise enough authorial control over the experience of a game. Ebert has gone on to make no attempt to justify or defend his remark or engage in any kind of debate, other than to allow, five years after the original remark, that he should have kept his opinion to himself.7

As I’ve made clear above, Ebert is wrong about videogames as a form. But frankly, I don’t care whether Ebert is wrong or not. Achieving “artistic legitimacy” is not a good reason to transform videogames. Who legitimizes art? To cede the right to decide the value of games to an authority that has nothing to do with games—or to concede the right to decide what is and is not art to any authority outside of the artist—is a dangerous trap. Creation is art. It doesn’t need validation beyond that.

What it needs is to be free. That an art form exists should be justification enough for people to be able to contribute to it, to work in it. We finally have the means to allow more than just programmers and big game publishers to create games—and the vast majority of people in the world aren’t computer engineers, or designers employed by Epic Games. What do we gain from giving so many people the means to create games? We gain a lot more games that explore much wider ground, in terms of both design and subject matter. Many of these games will be mediocre, of course; the majority of work in any form is mediocre. But we’ll see many more interesting ideas just by the sheer mathematical virtue of so many people producing so many games without the commercial obligations industry games are beholden to. Remember, I’m talking about hobbyists, people who make games in their spare time with the tools they have on hand. And even if a game isn’t original, it’s personal, in the way a game designed to appeal to target demographics can’t be. And that’s a cultural artifact our world is a little bit richer for having.

To visualize this new world of games, think about network television versus YouTube. The former spends a lot of money and time creating content designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator. Because network shows need to justify themselves monetarily—they need to catch enough viewers to earn advertising dollars—they can rarely afford to be brilliant, daring, or bizarre. (Sometimes a director has enough force of will, and fights the network hard enough, to create a show that is all of these things. But it’s certainly not the norm.)

YouTube: millions of videos from millions of authors. Most of them are mediocre: boring, familiar, or unwatchable. That’s to be expected in an arena where everyone is allowed to contribute. But others are sublime, brilliant, valuable: Grishno’s “Transgender in New York” videos,8 wendyvainity’s surreal computer animations and music,9 or shaneduarte’s Simpsons remixes.10 As long as there’s some sort of infrastructure, valuable works—those by both dabbling amateurs and dedicated artists—can reach their audiences. YouTube has its own infrastructure of user ratings and featured videos, but people are just as likely to share the addresses of specific videos with the friends they think those videos will appeal to. And there’s far more value in the collective content of YouTube—even given that there are more piles of trash than treasure—than in the collective content of a television network, simply as a function of the number of people contributing and the overwhelming volume of their contributions. YouTube’s content is far more diverse, too, since involvement in the television industry isn’t a requirement for entry. Network television shows are all made by professionals working in the field, a far smaller set of people than the set of people who own webcams. YouTube’s content is made much more quickly and cheaply because it’s not (usually) designed with a commercial agenda: videos can be recorded and broadcast, and their value assessed later.

YouTube also gives people the means to make videos of themselves, their friends, their babies, and their puppies—video snapshots—not for the world at large, but for their social circles and themselves. YouTube is a means of transmitting a video directly from the author to an audience—one that can be as small and specific as the author desires. Videos become more specialized, and hence more personalized. A medium that was formerly accessible only to those with money and training can now be used by anyone for personal ends. If Internet television is in the process of reinventing television, imagine how game design tools for nonprogrammers and the free distribution of games online might reinvent videogames.

The Culture of Alienation

Limiting the creation of games to a small, exclusive group leads not only to creative stagnation, but also to the alienation of anyone outside that group. I’ve described the round-the-drain cycle the games industry is in: games are designed by a small, male-dominated culture and marketed to a small, male-dominated audience, which in turn produces the next small, male-dominated generation of game designers. It’s a bubble, and it largely produces work that has no meaning to those outside that bubble, those not already entrenched in the culture of games.

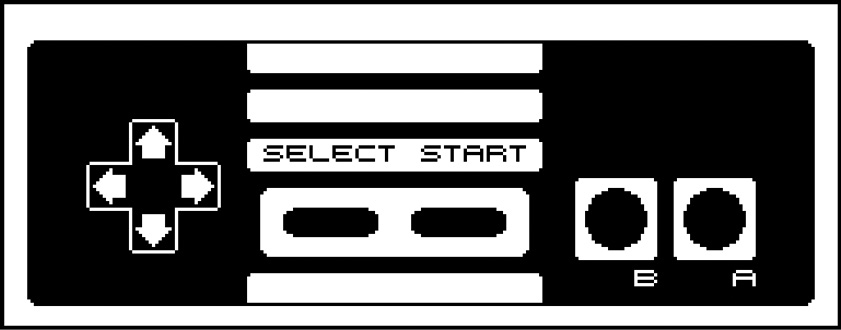

There are mechanical consequences as well. Look at how game controllers have changed as their audiences changed. The home game machines of the 1970s and ’80s, which marketed themselves to large, general family audiences, had the simplest control pads. The Atari Video Computer System (or the Atari 2600) is a simple joystick with a single button. And here is the design of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) controller, released in the United States in 1985:

The NES controller has a four-way compass rose and two prominent red buttons. (There are also two buttons in the center for secondary functions like pausing the game, but the design of the controller clearly communicates that they’re peripheral.) You use the compass to navigate your character or cursor. You use the buttons to perform actions.

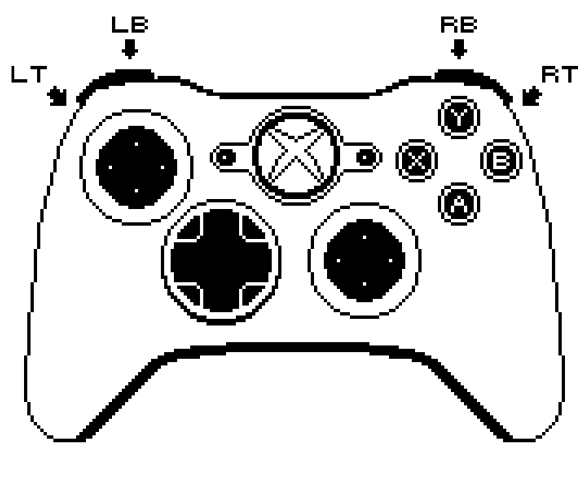

After over thirty years of catering to an audience that is continuously playing and learning games—an audience that hence requires more and more complicated games to interest it—games and the controllers with which players interact with them have become more and more complex. This is not to say different: layers of complexity have simply been added to the same few models of games and the same few models of controllers. Here’s the controller for the Xbox 360, released in the United States in 2005:

The Xbox 360 controller is the same model as the NES controller: held between two hands, with navigational functions assigned to the left hand and manipulation verbs to the right. But instead of a single navigational pad on the left, two verb buttons on the right, and two option buttons in the center, the Xbox pad has a navigational pad plus a stick on the left, four verb buttons plus another stick on the right, four “shoulder” buttons on the top of the controller (two to each side), plus three option buttons in the center. (Additionally, some games call for the player to “click” either of the sticks in like a button, adding two more verbs.)

The means players use to interact with games guides the design of those games. A game for the NES might have a button for jump and a button for shoot, and the compass rose directional pad for moving a character left and right. You can imagine the kinds of games that are designed for eight buttons and four sticks. Imagine introducing someone who had never seen a movie before to Matthew Barney’s Cremaster films. The amount of both manual dexterity and game-playing experience required to operate a game designed for the Xbox 360 makes play inaccessible to those who aren’t already grounded in the technique of playing games. And to attain that level of familiarity with games requires a huge and continuous investment of time (and money—keeping up with new games costs bucks). This means that older people—people with families and obligations, people trying to raise kids, or any people with a lack of free time to invest—have a harder time gaining access to games. At the same time, as a side effect of this unnatural selection, commercial games become longer and longer, with game covers advertising dozens and occasionally hundreds of hours of gameplay. (Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3, a PlayStation 2 game from 2008, advertises a “70+ hour game” on the back of its box.) Who has that much time to invest in playing a videogame? Answer: the target audience of most of the industry’s games, a mostly young and mostly male audience that has few obligations and plenty of disposable income.

The culture that this audience creates and exists within is one of in-jokes and brand worship, rituals to establish whether the participants are in or out of the tribe. It’s an exclusive culture, an alienating environment that speaks only to itself. Its interactions with the outside world are decidedly hostile.

Destructoid, one of the most popular sources for videogame news on the Internet, employs a writer named Jim Sterling who once called my girl a “feminazi slut” on Twitter. This isn’t some rogue nerd; this is a “journalist” whom Destructoid employs to write on such topics as whether the penis is more powerful than the vagina because it can rape,11 or on whether female Mortal Kombat characters have secret cocks.12 And lest you think that such a character couldn’t possibly be taken seriously, hundreds of his readers responded publicly to my open letter to Destructoid complaining about Sterling’s behavior in an attempt to bully and shame us.13 How is a woman, a trans person, or any rational individual expected to feel safe enough to participate in such a community?

What I want from videogames is for videogames to speak to more than just the handful of people already engaged in producing and consuming them. To de-monopolize game creation is to de-monopolize access to games.

Beyond Consumer

In an era when the Internet makes it easy to transmit and disseminate media, there’s no reason for people to accept that their only contribution to the growth of an art form is as a consumer, supporting “elite” creators with money.

I’ve wanted to make videogames since I played Fukio Mitsuji’s NES game Bubble Bobble as a kid. I drew characters on construction paper, cut them out, and laid out obstacle courses for them to navigate—Bubble Bobble stages on hardwood floors. But the technical leap to digitize my designs was beyond my reach. Programming was something mystical and arcane. I came into contact with code sometimes: the most basic BASIC examples. But something as simple as making a picture of a character move across a screen required a working knowledge of control loops, writing to video memory buffers, and advanced bit-shifting math—all of which was so inaccessible to me as a kid that I sublimated my childhood desire to make games until well into my adulthood.

It’s not like it was then. There’s a commercial product in videogame stores right now—Warioware: D.I.Y., from Nintendo—that allows players to create their own small games.14 What Warioware: D.I.Y. does is to introduce its players to the concept of designing rules, of using art and sound to communicate the state of the game to the player, of scripting the events of a game and of working cleverly within limitations. For kids today, digital game creation doesn’t have to be the mystical process it was when I was little.

Kids today also have tools like Stencyl,15 a free tool for making games and distributing them online. A website collects kits and resources contributed by the entire community, which are all made available to an individual creator for use in her game. The rules are put together in Scratch,16 a system designed by programmers at MIT for young children to use. It involves snapping simple instructions together like LEGOs.

But before things like Stencyl and Warioware existed, I made games and digital stories however I could: an old DOS shooting-game creation program that I can no longer remember the name of, the track editor in Nintendo’s Excitebike, an editor for creating worlds made out of text called ZZT. People with something to say will always manage to find ways to say it, and there’s a history of clever people using whatever means they can find to modify and subvert digital games and to create new ones—to engage with games in a role beyond consumer. Today, this process is easier than ever.

The Big Crunch

This same false sense that the knowledge needed to create videogames is unattainable without special institutional training is the same carrot the Big Games Industry uses to entice wannabe game artists into taking jobs within their system—and putting up with insane hours and ridiculous working conditions. There exists within the games industry a phenomenon called “crunch mode”: working sixteen-hour days, staying at work until the game you’re being paid to make is finished. This isn’t something you’re asked to do—it’s expected, a standard condition of the job. And it’s likely the reason most people in the games industry, their physical and mental health fizzled, burn out and quit within a few years, forced to retrain and find a new career. According to the International Game Developers Association (IGDA), the closest thing the industry has to an advocacy group for employees, 34 percent of game developers expect to leave the industry within five years, and 51 percent—half of them!—expect not to last a decade.17 That’s lunacy.

The industry gets away with this because it’s convinced its employees that these jobs are the only gateway to videogame creation. “We’ve graciously allowed you to fulfill your childhood dream of making games. We’re even paying you for it! And what’s more, we’re the only way you’ll ever be able to do that.” Mike Capps, a former member of the board of directors at the IGDA and the president of Epic Games said that Epic expected employees to work more than sixty hours a week and in fact only hired people they expected to be willing to do so.18 The IGDA has no official stance on the hours of unpaid overtime the people it claims to represent are obliged to do by their employers.

Since the industry sees itself as ubiquitous—as the only possible means of creating games—it feels no need to change itself for the benefit of either its employees or its art. Which is another reason why carving new paths to game creation and distribution is valuable. By undermining the industry’s claim to being the only route to game creation—especially to making a living from game creation—we force the industry to reconsider its totalitarian attitude toward the people it employs. Publishers need creative people to make games for them. We have one foot in an era when creative people will no longer need publishers to distribute their games.

Creating more and better games will also challenge the industry creatively. Spending millions of dollars to remake the same seventy-hour-long games for the same small audience is no longer feasible when so many people want different experiences out of games and have the means to find them elsewhere. Games from hobbyists have the potential to change the dominant format of the videogame: instead of seventy-hour multimillion dollar games that sell for sixty bucks apiece, digital games can be short and self-contained—less than an hour, short enough to fit comfortably into an adult player’s day. The focus of games could shift from features, the ways in which a game is differentiated from similar games—thirty hours of play, twelve unique weapons, advanced four-dimensional graphics acceleration—to ideas. Take Tarn Adams’ WWI Medic19 for example: a game not about chain-gunning enemy soldiers but about trying to patch them up as the bullets cut them down. Saving even a single soul—climbing out of the trench, grabbing a fallen body and lugging it back to safety under a senseless hail of bullets—is incredibly difficult. The game takes minutes to play, and communicates an idea about war that may perhaps be more valuable than space marines frotteurizing each other with chainsaws.

Smaller games with smaller budgets and smaller audiences have the luxury of being more experimental or bizarre or interesting than 12 million dollar games that need to play it as safely as possible to ensure a return on investment. Imagine what a videogames industry that wasn’t fixated on hits—that wasn’t required to make hits—would create.

What Are Games Good For?

But even given all of this, why worry about the accessibility of digital game creation at all when other forms—like the short story or novel—are already established and available for non-professionals to work in?

Answer: because different forms are suited to different kinds of expression, and some are more effective at communicating in certain ways than others. Broadly, films and photographs are best suited for communicating action and physical detail. Novels are best suited for communicating internal monologue and ambiguity.

What are games best suited for? Since games are composed of rules, they’re uniquely suited to exploring systems and dynamics. Games are especially good at communicating relationships; digital games are most immediately about the direct relationship between the player’s actions or choices and their consequences. Games are a kind of theater in which the audience is an actor and takes on a role—and experiences the circumstances and consequences of that role. It’s hard to imagine a more effective way to characterize someone than to allow a player to experience life as that person.

Take, for example, a game called We the Giants.20 Most people who connect to this game’s website in order to play it—taking the role of a squat, block-like cyclops—will be unable to reach the game’s goal, a star high in the sky. Rather, most players are given the responsibility of voluntarily dying in a position that will allow future players to use their solidified bodies as steps in a staircase leading skyward. Each player guides her cyclops to the position of its sacrifice, presses a button, types a single message to future players of the game, and watches the cyclops’s eye close forever. Thereafter, the player is never allowed to play the game again; logging on to the website, she can only watch the ongoing progress of the staircase of which her body is a part.

That’s a pretty compelling way to explore themes of sacrifice in a work: to ask players actually to make a sacrifice, and to show them the meaning of that sacrifice over the course of generations. This is something games are almost uniquely capable of doing, and we haven’t even begun to explore the possibilities of this kind of expression.

It’s also the sort of experience—a minutes-long game in which the player is asked to commit voluntary suicide and never allowed to play again afterward—that is unlikely to come out of a commercial publishing system that needs its creations to sell millions in order to justify their having been made. The author of We the Giants, Peter Groeneweg, is a student and created the game as part of a monthly “experimental gameplay” challenge.21

The ability to work in any art form with the digital game’s unique capabilities for expression shouldn’t be restricted to a privileged (and profit-oriented) few. If everyone is given the means to work in an art form, then we’ll invariably see a much more diverse, experimental, and ultimately rich body of work. In a speech at the 2007 Game Developers Conference, Greg Costikyan—a board and videogame designer and critic of the games industry—said: “I want you to imagine a 21st century in which games are the predominant art form of the age, as film was of the 20th, and the novel of the 19th.”22

This is what I want from videogames, and this is what I’m trying to help you imagine. Throughout the rest of this book, I hope to help you imagine how this transformation of games—and the role games will play in the art and culture of the twenty-first century—is not only necessary, but inevitable.

Footnotes

1 I’ll use this term interchangeably with “digital games” and “electronic games” throughout this book.

2 ESA, 2009 Sales, Demographic and Usage Data: Essential Facts about the Computer and Video Game Industry, p. 2, http://www.theesa.com/facts/pdfs/ESA_EF_2009.pdf.

3 Ibid, p. 10.

4 For insight into the Michfest controversy, see http://www.auntiepixelante.com/?p=1247. Also, I don’t mean to imply that all of these artists have taken a position on Michfest. I’m really just disappointed in Diane Dimassa.

5 Tim Sweeney, “End of the GPU Roadmap” (keynote address, High Performance Graphics 2009, New Orleans, August 3, 2009), http://www.highperformancegraphics.org/previous/www_2009/presentations/TimHPG2009.pdf.

6 Sea life joke courtesy Emily Alden Foster.

7 “I was a fool for mentioning video games in the first place. I would never express an opinion on a movie I hadn’t seen. Yet I declared as an axiom that video games can never be Art. I still believe this, but I should never have said so.” Roger Ebert’s Journal, “Okay, kids, play on my lawn,” July 1, 2010, http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/2010/07/okay_kids_play_on_my_lawn.html.

11 Jim Sterling, “How Aliens are blatantly better than Predators,” Destructoid, February 9, 2010, http://www.destructoid.com/how-aliens-are-blatantly-better-than-predators-162754.phtml.

12 Jim Sterling, “Why Penis Why?: MK vs. DC’s Kitana looks . . . lumpy,” Destructoid, August 5, 2008, http://www.destructoid.com/why-penis-why-mk-vs-dc-s-kitana-looks-lumpy-98300.phtml.

13 Anna Anthropy, “An Open Letter to Destructoid on Jim Sterling’s Misogyny,” Auntie Pixelante, http://www.auntiepixelante.com/?p=912.

14 Because Nintendo controls the infrastructure by which five-second Warioware: D.I.Y. games are distributed, or even allowed to exist, transmission of those games from creator to creator is fairly restricted. What most creators do, in fact, is publish videos of themselves playing their games on YouTube.

17 Casey O’Donnell, “Quality of Life in a Global Game Industry,” International Game Developers Association, http://www.igda.org/articles/codonell_global.

18 Greg Costikyan, “Mothers, Don’t Let Your Children Grow Up to Be Game Developers,” Play This Thing!, April 3, 2009, http://playthisthing.com/mothers-dont-let-your-children-grow-be-game-developers.

20 Playable online at http://wethegiants.thegiftedintrovert.com.

21 “Best of the Net: Art Game,” Experimental Gameplay Project, January 1, 2010, http://experimentalgameplay.com/blog/2010/01/best-of-the-net-art-game.

22 Greg Costikyan, “Maverick Award Speech,” Man!festo Games, March 14, 2007, http://www.manifestogames.com/node/3413.