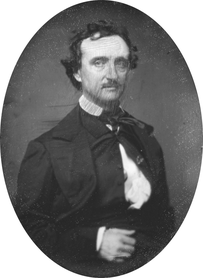

This image of the damaged Traylor is reproduced with permission of the Poe Museum.

Lauren Curtright

Poe’s Body

In his address to the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore at the society’s meeting to mark the centennial of the death of its eponymous author, Allen Tate reminisced about reading his family’s works of Poe. He attributed his favoritism for one of these volumes to its resonance with his own precocious ambitions: “In this volume I am sure, for I read it more than the others, was the well-known, desperate, and asymmetrical photograph, which I gazed at by the hour and which I hoped that I should some day resemble.”[1] Given that, according to Tate, this set of Poe’s works contained the signature of Tate’s great-grandfather, who died in 1870, it was probably Rufus Wilmot Griswold’s The Works of the Late Edgar Allan Poe (1850–1856). Notwithstanding Tate’s confidence in his memory, it must be fictitious, because the publishing industry did not use photogravure until the 1880s.

Tate’s memory passes as legitimate because it participates in a long-standing tradition of looking to Poe’s photographic record to re-view Poe.[2] Tate’s misremembered “photograph” matches the Ultima Thule, “one of the most celebrated literary portraits of the nineteenth century.”[3] Tate recalls the Ultima Thule to introduce his argument that Poe’s writings are important, despite their “blemishes,” or marks of Poe’s “provincialism of judgment and lack of knowledge.”[4] Tate thus appeals to photography to redeem Poe from Griswold’s scathing verbal portraits of the author, in Griswold’s infamous obituary of Poe and preface to the aforementioned edition of Poe’s works—portraits that long influenced Poe’s reception in the United States. Like the title of his lecture, “Our Cousin, Mr. Poe,” Tate’s substitution of the Ultima Thule for what was probably John Sartain’s mezzotint engraving of Poe based on a circa-1845 oil painting by Samuel Osgood illuminates Tate’s investment in Poe’s legacy. For Tate, positioning Poe within a lineage of renowned American writers required establishing Poe’s cousinship with Tate himself and his audience. As an index, a photograph seems a more reliable indicator of genealogy than a painting.

I link Tate’s manipulation of the Ultima Thule to a prior modernist instance of remaking Poe through mechanical reproductions of Poe’s body. The earlier instance comprises two adaptations of images of Poe, one by the literary scholar George Edward Woodberry and the other by the journalist Thomas Dimmock, both of which appeared in the Century Magazine around 1895. Their sources are Poe’s last two daguerreotypes, taken just weeks before Poe’s death—the Traylor and the Thompson—and one of the Thompson’s progeny, a daguerreotyped copy of the Thompson named the Players Club. Taken together, Woodberry’s and Dimmock’s adaptations of Poe offered readers of Century a means to both fix and fixate on social categories in the face of epistemological and technological change.

This image of the damaged Traylor is reproduced with permission of the Poe Museum.

The Thompson belongs to the Edgar Allan Poe Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. This image of the Thompson is reproduced with the Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s permission.

The Players Club daguerreotype belongs to Susan Jaffe Tane. The image here is reproduced with her permission.

The altered “mode of perception” that Walter Benjamin attributes to the invention of photography, coupled with the fact that the Thompson and the Traylor were taken so close in time to Poe’s death, inspired reanimations of these daguerreotypes of Poe in an effort to remake Poe’s image at the turn of the twentieth century.[5] Literary critic Thomas Carlson claims that a “counterpoint” to the “Griswoldian” image of Poe had been established in the United States by 1900 and that American silent films of this period extended this counterpoint by producing “a view of Poe as brilliant victim.”[6] Thus Poe’s remaking, which made it possible for him “to join the first rank of American writers,” relied as much on moving images as on their still counterparts.[7] However, when D. W. Griffith committed to Poe’s reanimation as “a familiar and recognizably beset citizen of early twentieth-century America” with his short biopic Edgar Allen [sic] Poe and his feature-length film The Avenging Conscience; or, ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’ (1914), Poe’s credence was already tied to photographic renderings of Poe’s body.[8]

Poe’s alignment with photography seems logical because, like Poe’s oeuvre, indexical media are often associated with the supernatural. The discourse on photography envisions this medium as magical, as well as veracious, and endows it with mystery. If the sordid, fantastic, or—to borrow one of Poe’s key words—outré qualities of the dramas of daguerreotypes of Poe that I present here complement Poe’s writings, then they also characterize photography as a quintessentially gothic medium. However, the gothic features of daguerreotypes of Poe are also modernist if we define modernism by the epistemological shift that occurred between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, evident in such diverse arenas as physiology, philosophy, physics, sociology, linguistics, and modernist painting, in which, as Mary Ann Doane argues, reality came to be explained by laws of probability. Doane claims that, during this period, belief in chance grew with modernity because chance makes newness possible; however, chance requires presence. A move away from referentiality eroded confidence in presence, which led to fascination with the possibility of representing the instant. Especially problematic to turn-of-the-century epistemology was the theory of the afterimage, which came to dominate physiological explanations of how spectators perceive motion in film. According to this theory, the image in one frame appears to run into the next because spectators’ retinas retain images, creating the illusion of motion and the sense of a continuum between past and present on screen. While the theory of the afterimage helps explain how cinema achieves its effects, it also heightens anxiety about human access to the real; hence “the desire for instantaneity emerges as a guarantee of a grounded referentiality.”[9] In response to this anxiety, “photography and the cinema produce the sense of a present moment laden with historicity at the same time that they encourage a belief in our access to pure presence, instantaneity.”[10] In their resolute insistence on the power of chance, narratives about the creation, reproduction, and circulation of the last daguerreotypes of Poe assert that these images capture their referent, Poe, in one of his last instants.

While set in the antebellum United States, the story of the final reproductions of the living Poe has its origins in the modernist period: it first appeared in print in Dimmock’s 1895 letter to Century—a letter titled “Notes on Poe.” Despite the actual capacities of the earliest photographic technology, in the same year as film debuts, Dimmock reanimates Poe as an important figure of American letters by presenting a cinematic view of his daguerreotype of Poe. The length of exposure that a daguerreotype requires depends on a number of factors, including devices (e.g., lenses and reflectors) used to produce the (reversed) image inside the camera obscura, atmospheric conditions, available light, and chemicals applied to the plate to fix the image. Consequently, the sitting time for a daguerreotype varies according to the times of day and year and the distance from the equator at which the image is made. Still, we know that Poe would have had to sit for many instants while having his “likeness” made in William Abbott Pratt’s studio in Richmond, Virginia, in 1849—a sitting that produced two daguerreotypes, which were later named the Thompson and the Traylor. Regardless, “Notes on Poe” imbues one of these last daguerreotypes of Poe with instantaneity by suggesting that Pratt captured Poe candidly and in motion with his camera. Dimmock, thereby, constructs what Doane calls “a present moment laden with historicity” by giving the impression that the original (the Thompson) of Dimmock’s daguerreotyped copy of Poe (the Players Club) and, indeed, Poe himself are accessible through their reproductions.[11] At a moment when referentiality is in crisis, Dimmock presents his daguerreotype of Poe as an index of its subject—as facilitating the invasion of the present by the past—to reassure his readers that it reproduces the “real” Poe and to validate his own perceptions of Poe crystallized during investigations in Richmond and Baltimore decades before writing his letter to Century.

Recognizing that a story of origins is antithetical to theorizing reproductions, I am nonetheless compelled to locate another beginning in my analysis of adaptations of Poe: Poe’s ending. Although the mystery of Poe’s death has long been a favorite topic of Poe aficionados and detractors alike, the equally intriguing stories of the image-objects closely associated with his death have escaped a full investigation. Less than one month before Poe died in Baltimore, Pratt—a daguerreotypist, engineer, and Gothic Revivalist architect—encountered Poe on the street outside Pratt’s studio in Richmond, which Pratt soon thereafter named the Virginia Sky Light Daguerrean Gallery at the Sign of the Gothic Window. Against Poe’s mild protest that he was not properly dressed to be daguerreotyped, Pratt convinced Poe to come upstairs and sit for what became Poe’s final mark on what Poe describes as “the beautiful art of photogeny.”[12] Or so Dimmock’s story goes in “Notes on Poe.”

Exhibited in Pratt’s street-level display case until he sold his studio in 1856; presented to John Reuben Thompson, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, who loaned his daguerreotype of Poe to “a number of artists and photographers” for reproduction; and subsequently passed through the hands of a series of inheritors, the Thompson is now securely contained in Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library.[13] Its variant, however, met a dramatic end. Deas speculates that, to the devastation of its namesake and owner at the time (Robert Lee Traylor), the Traylor was completely destroyed after it “was damaged beyond repair” when Chicago publishers Stone & Kimball attempted to clean the plate in preparing to reproduce the image as the frontispiece to Woodberry and Edmund Clarence Stedman’s The Works of Edgar Allan Poe in 1894.[14]

As for the indeterminate number of copies of the Thompson, one not only survived the nineteenth century but also made news recently in print, on television, and on the Internet. On October 17, 2006, the Players Club was auctioned at Sotheby’s in New York for $150,000. Occurring less than a year after its recovery by the FBI, the Players Club’s sale benefited its late owner, the Hampden Booth Theatre Library. Sometime after 1981, the Players Club went missing from Hampden Booth. It resurfaced in 2004, when one Sally Guest, unaware of the object’s provenance, purchased it for $96 from an “antique/junk shop” in Walnut, Iowa.[15] Guest appeared with the Players Club on an episode of PBS’s Antiques Roadshow in early 2005. After displaying it on her mantle for over a year, Guest decided to sell it and contacted the Poe Society to authenticate it. By its signature scratch across the image of Poe’s face, Deas, whom the Society consulted, recognized the daguerreotype as belonging to Hampden Booth. The FBI then restored the Players Club to the theater, who soon thereafter sold it to the highest bidder at Sotheby’s.[16]

The perception that photography grants privileged access of a different order than painting, illustration, sculpture, or writing to the subject it represents has captivated the public’s imagination since the invention of daguerreotypy in 1839. This belief accounts for the impressive value accrued by Pratt’s daguerreotyped copy of a daguerreotype of Poe. It also belies what Benjamin theorizes as the radical potential of technologies of reproducibility. Writing in exile from Nazi Germany in Paris in the winter of 1935–1936, Benjamin famously characterized the impact of technological reproducibility on the superstructure as the loss of the “aura,” or “the here and now of the work of art—its unique existence in a particular place”—which “underlies the concept of [the artwork’s] authenticity.”[17] The belief that an object possesses authenticity supports “the idea of tradition which has passed the object down as the same, identical thing to the present day.”[18] To Benjamin, the concept of authenticity works to suppress the masses; thus photography’s demise of the aura enabled what Benjamin calls the politicizing of art. It signaled the possibility of “the liquidation of the value of tradition in the cultural heritage” and the “alignment” of “reality with the masses.”[19] At the time of Benjamin’s writing, traditional concepts were being “used in an uncontrolled way,” which “allow[ed] factual material to be manipulated in the interests of fascism.”[20] Likewise, reproductions of Poe’s body have been directed toward upholding the concept of authenticity in American racial discourse, which posits “pure” whiteness and mandates the conceptual and biological reproduction of whiteness through laws against miscegenation. Woodberry’s and Dimmock’s adaptations of Poe engage in this racial discourse as they place Poe at the center of turn-of-the-century negotiations of new forms of technological reproducibility.

Capitalizing on the symbiosis of Poe’s images, texts, and biography in the imaginations of the American public and literati, Woodberry featured reproductions of daguerreotypes of Poe in his three-part series “Selections from the Correspondence of Edgar Allan Poe,” published in Century in the fall of 1894. With a circulation of over 200,000 in 1890, Century was famous for its woodcut illustrations and writings by premier authors of the period. However, during the 1890s, publications that converted to the half-tone process for printing photographs began to edge out Century, and Century’s readership declined to 150,000 by the end of the decade. Through a series of articles in the 1880s that created “a sensation in the magazine press,” Century reinvigorated debate about the Civil War and promoted reconciliation between white Northerners and Southerners largely through absolution of the South for slavery.[21] As historians have discussed, including Rayford W. Logan, who labels this period the “nadir” of African-American history, the turn of the twentieth century witnessed a rise in violence against African Americans and the endorsement of this violence by national policies of racial segregation and disenfranchisement, exemplified, respectively, by Plessy v. Ferguson and the overturning of the Civil Rights Act of 1875.[22] Even as it served as a venue for African-American writers, Century was a white magazine implicated in “a snowballing of racist ideas and practices, both of which reached unprecedented vehemence in the 1890s.”[23] Thus Woodberry’s series on Poe and Dimmock’s letter in response to it could be interpreted in relation to technological innovation, historicization, and racism at the turn of the twentieth century.

In “Poe in New York,” the final installment in his series on Poe, Woodberry heads Poe’s correspondence with an image of an engraved portrait of Poe, captioned as “From a Daguerreotype Owned by Mr. Robert Lee Traylor.” The caption identifies the source of this image as the Traylor, Pratt’s second daguerreotype of Poe, taken during the same sitting as the Thompson. A footnote to this caption announces that Woodberry and Stedman’s ten-volume edition of Poe’s works would also include the images featured in Century; thus this footnote converts the Traylor into a trailer of sorts. It also gives an abbreviated history of a daguerreotype that was “presented by Poe, a short time before his death, to Mrs. Sarah Elmira (Royster) Shelton” (Poe’s last fiancée) and that is “believed to be [Poe’s] last portrait.”[24] As Deas explains, the Traylor differs only slightly from its variant, the Thompson.[25] Therefore, the individuality of these images is easy to overlook, especially through a printed copy of an engraved reproduction. It is unsurprising, then, that Dimmock mistook the image heading “Poe in New York” as a copy of the Thompson—the daguerreotype that Pratt had copied for him in Richmond forty years earlier. It is remarkable, however, that Woodberry’s alleged mistake in identifying the source of this image so disturbed Dimmock that he responded to “Poe in New York” with “Notes on Poe.”

The image of Poe heading Woodberry’s article is similar to a press photograph in that it is accompanied by texts: a title, subtitle, caption, footnote, and an article composed of Woodberry’s introduction and a selection of Poe’s letters. Roland Barthes argues that, by analyzing “the code of connotation of . . . the press photograph[,] we may hope to find, in their very subtlety, the forms our society uses to ensure its peace of mind.”[26] By captioning the reproduced engraving based on the Traylor as “From a Daguerreotype . . . ,” Woodberry adorns the image with what Barthes calls “the ‘objective’ mask of denotation.”[27] It is to Woodberry’s claim of the denotative status of this image that Dimmock responds. Dimmock’s letter is yet another appendage to Century’s copy of the Traylor . Like a caption, Dimmock’s letter “appears to duplicate the image, that is, to be included in its denotation,” and it “loads the image, burdening it with a culture, a moral, an imagination.”[28] In result, a text, formerly “experienced as connoted[,] is now experienced only as the natural resonance of the fundamental denotation constituted by the photographic analogy and we are thus confronted with a typical process of naturalization of the cultural.”[29] Dimmock participates in this “naturalization of the cultural” by claiming that an indexical relation exists between “Notes on Poe” and his daguerreotype of Poe. Barthes’s theory of the photographic message helps clarify how, as a mode of communication, “Notes on Poe” functions to “reassure” its readers that Poe was an ideal citizen and that, therefore, his writings were a solid foundation for an American literature.[30] Dimmock does this by molding Poe into a model of white, middle-class masculinity. Just as Tate, in his 1949 lecture to the Poe Society, uses a photograph to reassure his audience that Poe is a relatable figure, Dimmock capitalizes on his readers’ belief that a photograph represents indisputable truth in order to make his new, more “gentlemanly” image of Poe seem to reflect reality.

In Dimmock’s first note on Poe, he describes his viewing of Pratt’s original daguerreotype of Poe, his subsequent conversation with Pratt, and his purchase of Pratt’s daguerreotyped copy in Richmond “during the Christmas holidays of 1854–1855.”[31] Contrary to Woodberry’s claim that the Traylor was an original daguerreotype that Poe gave to Elmira Shelton, Pratt described Shelton’s daguerreotype as a copy to Dimmock, which Pratt sold to her soon after Poe’s death. By this, Dimmock presumes that Pratt meant that Pratt made for Shelton—as he did for Dimmock—a daguerreotyped copy of the original daguerreotype in his street-level display case. However, in light of Deas’s finding that Pratt did, indeed, give the Traylor to Shelton and of the fact that the image of Poe that heads “Poe in New York” is not reversed from the Thompson, we may conclude that its unidentified artist worked from one of Pratt’s “original” daguerreotypes of Poe. Dimmock’s narrative implies that Pratt, recognizing that to deny the originality of the Traylor would invest his displayed daguerreotype of Poe with uniqueness and, thereby, advance its copy’s sale, misled the journalist to believe that he had produced only one daguerreotype of Poe in his daguerrean gallery in 1849. Nevertheless, based on Dimmock’s recollection of his transaction with Pratt, which convinced him that Pratt was an honest man, in “Notes on Poe,” Dimmock presents the following flawed correction to Woodberry’s account of the Traylor:

Being satisfied then—as I am now—that Mr. Pratt told the truth concerning his daguerreotype, I at once offered to buy it; but naturally enough he declined to sell what, even then, was of considerable value. He told me, however, that he had made an excellent copy for the lady to whom Poe was engaged (not mentioning her name), and would make me one if I so desired. He did so, and this copy is now in my possession, in perfect preservation, after forty years. It is in every respect, so far as I am capable of judging, quite as good as was the original; but it is not the original, nor, I am inclined to think, is that of Mr. Traylor. Where the original now is, I do not know; but whoever examines it, or a good copy, closely, will see that the picture is not such a one as Poe would be likely to give to the lady of his love. . . . Doubtless [Pratt] made several—perhaps many—copies after mine; but I am quite certain of the genuineness and fidelity of my own.[32]

Dimmock’s haughty defense of his daguerreotype reveals several aspects of the significance of portrait photography to Americans at the fin de siècle. His admissions that “it is not the original” and “not such a one as Poe would be likely to give to the lady of his love” and “doubtless [Pratt] made several—perhaps many—copies after [his]” are essential to counter Woodberry’s claims about the Century’s source daguerreotype and to justify Dimmock’s compulsion to write his letter. However, they also depreciate the value of Dimmock’s copy of the Thompson .

While Benjamin argues that technological reproduction has the radical potential to abolish the concept of authenticity, Dimmock’s letter privileges this concept. However, “Notes on Poe” also reveals the extent to which the belief that a photograph represents reality mutates the idea of authenticity. Dimmock relies on a discourse of originality to describe his portrait of Poe, which he claims “is in every respect, so far as [he is] capable of judging, quite as good as was the original,” and of which he “is quite certain of the genuineness and fidelity.” However, the mood of his letter disavows its rhetoric and suggests that Dimmock and his readers actually appreciate replication. Dimmock is clearly invested in his daguerreotyped copy and regards it as an index of its subject, Poe. Similarly, a century later, whoever stole the Players Club from Hampden Booth, the temporary owner of the image (Sally Guest), its appraiser on Antiques Roadshow (C. Wesley Cowan), and the participants in its auction at Sotheby’s overlooked the derivativeness of this daguerreotype. By recognizing that a photograph is a copy to begin with, they all saw the Players Club as “quite as good as was the original” and, therefore, as possessing “considerable value.” In contrast to a photograph, a daguerreotype is a positive print. To mechanically reproduce it, one must take a daguerreotype (or a photograph) of it, as Pratt did for Dimmock. Thus, perhaps one cannot say of the daguerreotype—as Benjamin says of the photograph—that, “to ask for the ‘authentic’ print makes no sense.”[33] However, to ask for its original makes very little sense because a daguerreotype, like a photograph, is constitutively reproducible. This technical aspect of daguerreotype sanctions Dimmock to assert authority over Pratt’s first image of Poe even while Dimmock lacks—and dismisses the need to have—full knowledge of the Thompson’s provenance.

Ironically, in his second note on Poe, Dimmock unwittingly locates the daguerreotype from which Pratt made the Players Club. Here, he “condense[s,] into the briefest possible compass,” a story of a live encounter with Poe, using John Reuben Thompson’s “own words nearly as memory permits.”[34] Dimmock claims that Thompson related this “compass” to him in an interview in Richmond in 1860, during which the subject of Pratt’s daguerreotype of Poe apparently did not arise (unbeknownst to Dimmock, Thompson owned the Thompson at the time). In his letter, Dimmock uses his reconstruction of Thompson’s story of Poe to compensate for his lack of knowledge about the Thompson. Dimmock moves easily from discussing a copy of Pratt’s daguerreotype of Poe to providing secondhand and even thirdhand knowledge of Poe. His recourse to a verbal portrait of Poe as a substitute for a more complete illustration of the Thompson reveals Dimmock’s perception, as well as that of his readers, of the interchangeability of a photograph and its subject.

Thompson’s story of Poe seems to undermine but actually supports Dimmock’s interpretation of the Players Club. As Thompson related to Dimmock,

on going home for lunch my mother told me that a stranger had called to see me, and had left a message to the effect that for a week past a man calling himself Poe had been wandering around Rocketts (a rather disreputable suburb of Richmond) in a state of intoxication and apparent destitution, and that his friends, if he had any, ought to look after him. I immediately took a carriage and drove down to Rocketts, and spent the afternoon in a vain search—being more than once on the point of finding him, when he seemed to slip away. Finally, when night came on, I went to the most decent of the drinking-shops and left my card with the barkeeper, with the request that if he saw the alleged Poe again, he would give it to him. Ten days, perhaps, had passed, and in the press of occupation the matter had entirely gone from my mind, when on a certain morning a person whom I had never seen before entered the office, asked if I was Mr. Thompson, and then said, ‘My name is Poe,’ without further introduction or explanation. As, singularly enough, I had never met my townsman before, I looked at him with something more than curiosity. He was unmistakably a gentleman of education and refinement, with the indescribable marks of genius in his face, which was of almost marble whiteness. He was dressed with perfect neatness; but one could see signs of poverty in the well-worn clothes, though his manner betrayed no consciousness of the fact.[35]

On the one hand, Thompson’s observation that Poe was “dressed with perfect neatness” when he appeared at the office of the Southern Literary Messenger in 1849 is opposed to Dimmock’s reading of the Players Club. According to Dimmock, in his daguerreotype of Poe, Poe’s “dress is something more than careless,” “a white handkerchief is thrust, as if to conceal the crumpled linen,” his “coat is thrown back from the shoulders in rather reckless fashion, and the whole costume, as well as the hair and face, indicates that the poor poet was in a mood in which he cared very little how he looked.”[36] On the other hand, Pratt’s claim that Poe was reluctant to be daguerreotyped due to his unseemly clothing shows that Poe was, in fact, accustomed to minding his look. As Dimmock says, in the winter of 1854–1855, Pratt told him:

I knew [Poe] well, and he had often promised me to sit for a picture, but had never done so. One morning—in September, I think—I was standing at my street door when [Poe] came along and spoke to me. I reminded him of his unfulfilled promise, for which he made some excuse. I said, “Come upstairs now.” He replied, “Why, I am not dressed for it.” “Never mind that,” I said; “I’ll gladly take you just as you are.” He came up, and I took that picture. Three weeks later he was dead in Baltimore.[37]

Pratt’s anecdote suggests that, had his camera captured Poe in a less disastrous period than the weeks leading up to his death, Poe’s appearance would have been impeccable. Likewise, Thompson’s story indicates that Poe’s unsuitable attire when he encountered Poe was due, not to Poe’s inattention to his person, but to his poverty. Indeed, in Dimmock’s note, Thompson goes on to say of Poe, “His face was always colorless, his nerves always steady, his dress always neat.”[38] Refuting the facts of Woodberry’s footnote, Dimmock asserts that, even in his doomed state in September of 1849, Poe had sufficient presence of mind to recognize that his clothing would offend both his “lady-love” and posterity. Recorded in Pratt’s studio, Poe’s “disheveled” look—as Columbia University Libraries describe Poe’s appearance in this image—seems virtuous when coupled with Thompson’s claim that Poe’s “manner betrayed no consciousness of” the “signs of poverty in [his] well-worn clothes” when he allegedly appeared at Thompson’s office nearly coincidently as Pratt created the Thompson.[39]

Thompson’s statements about Poe in the flesh balance, rather than contradict, Dimmock’s claims about Poe’s image on a polished, silver-coated, copper plate. Together, they endow Poe with qualities associated with white, middle-class masculinity at the turn of the twentieth century. In “Notes on Poe,” Dimmock testifies that Poe was both attentive to his look and above vanity—that, without sacrificing his duty to his personal appearance, Poe was preoccupied by concerns more lofty than his clothing. Dimmock’s various depictions of Poe make a case that the author did, in fact, attend to his person but not excessively so—that is, not in such a way as might compromise Poe’s status as subject, not object, of the photographic gaze. Although Dimmock’s descriptions of Poe are largely about Poe’s clothing, they indicate attributes of Poe’s self and insinuate that, even more than a decorum for dress, there is a particular identity best suited for the camera. The seeming contradictions between its narratives make Dimmock’s letter function ideologically, at the same time as its basis in facsimile (daguerreotypes and reportage) supports the status of “Notes on Poe” as an index of its subject, allowing Dimmock to claim to, as Pratt did, “take [Poe] just as [he was].” “Notes on Poe” naturalizes a constructed image of Poe by asserting this image to be revelatory of the “real” Poe. Furthermore, by suggesting that daguerreotypes capture objects in motion (a “thrust” handkerchief, “crumpled linen,” and “coat . . . thrown back . . . in rather reckless fashion”) and abide by laws of probability, which enable a chance encounter on the street, in his descriptions of Poe in the Players Club and of the circumstances surrounding the production of the Thompson, respectively, Dimmock compares daguerreotypy to film, a medium even more strikingly veracious than photography because cinema represents motion. This retrospective reconfiguration of the capacities of daguerreotypy obscures that, in reviving Poe, Dimmock fashions Poe with a gendered, classed, and racialized identity.

In Thompson’s description of Poe, Dimmock invokes physiognomy, which is implicated in racism: Thompson allegedly claimed that Poe “was unmistakably a gentleman of education and refinement, with the indescribable marks of genius in his face, which was of almost marble whiteness.”[40] To readers of Century, the daguerreotyped image of Poe connotes knowledge of what constitutes an author at the fin de siècle. As an ideal, Poe is figured to have particular qualities at the same time as their particularity is disavowed in order to naturalize them: whiteness, in “Notes on Poe,” blurs into colorlessness. Through Thompson’s comparison of Poe to a marble statue, Dimmock imbues his image of Poe with a recomposed aura, performing what Miriam Hansen calls “the simulation of auratic effects.”[41] As Benjamin observes, sculpture produces works that “are literally all of a piece”; it is the art form most antithetical to technological reproducibility.[42] “Notes on Poe” tries to solidify Poe as the emblem of “traditional concepts—such as creativity and genius, eternal value and mystery.”[43] In the 1930s, Benjamin responded to the fascist corruption of the radical potential of technological reproducibility. In the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, a misuse of mechanical reproduction to reinforce an oppressive ideology also occurred, as exemplified by Dimmock’s adaptation of his daguerreotype of Poe.

Constructions of Poe at the turn of the twentieth century participate in a cultural process of replacing the sense of “the here and now” that is the aura with the “here, now” that is the index.[44] By this shift, reproductions become untied from the original artwork and its “unique existence in a particular place”; they move from one situation to the next, making the objects that they capture present to their beholders.[45] Thompson’s narrative about Poe embedded in Dimmock’s letter suggests that close encounters with originals leave one with a sense of the uncanny, or “the collapse of boundaries separating fantasy and reality, fiction and life.”[46] Poe’s supposedly abrupt appearance at the office of the Southern Literary Messenger in 1849 jolts Thompson: the famous writer’s sudden presence both startles and delights the editor. By the simple declaration “My name is Poe,” Thompson via Dimmock (or vice versa) raises Poe to the author function.[47] When Poe’s body is present to Thompson, Poe’s identity as an author is simultaneously sutured to and sundered from his person: it is at once made localizable and distributed everywhere. The singularity of this experience intensifies Thompson’s observational impulses; he regards Poe “with something more than curiosity.” Thompson’s resultant representation of Poe as the living dead registers the effect of this encounter with celebrity, the power that attends eye-witnessing an iconic figure and beholding his aura, but it also highlights the temporariness of Thompson’s editorship (a position that Poe had occupied twelve years before him) and provides Thompson with a glimpse of his own mortality.

In “Notes on Poe,” Dimmock figures originals of Poe as ghostly—as bodies relegated to the past but haunting the present through their copies. He invests these spectral replicas with greater value—both abstract and material—than their sources; each copy is “quite as good as was the original” precisely because the original merely was. In the present, originals are imaginatively if not actually lost, so that only their copies remain. However, truthfully, no originals exist in Pratt’s story. Despite the Richmond daguerreotypist’s fib, or Dimmock’s misinterpretation of Pratt’s information, the Thompson was not unique but, rather, one of a pair of daguerreotypes. The Thompson only became unique after 1894, when the Traylor was damaged and lost or destroyed. Furthermore, daguerreotypes are only perceived as originals by virtue of being positive prints. The fantastic logic in privileging the Thompson over the Players Club contends that by the interaction of light and chemicals, Poe’s body was literally captured on one of Pratt’s daguerrean plates.

In the modernist reconstruction of Poe bookended by Woodberry’s and Dimmock’s adaptations of Poe and Tate’s reminiscence about the Ultima Thule, we witness attempts to vindicate Poe by mechanically aligning him with a particular identity. Photography may be “the first truly revolutionary means of reproduction,” but it has also served reactionary politics.[48] The reproductions of Poe that I have discussed were not employed to meet “revolutionary demands in the politics of art [Kunstpolitik ].”[49] They salvage “the value of tradition in the cultural heritage” and accommodate that heritage to a filmic “mode of perception.”[50] By implicating the protocinematic qualities of Pratt’s daguerreotypes—their representation of motion and chance—in the cultural transformation of Poe into a norm of white, middle-class masculinity, “Notes on Poe” stymies the radical potential of technological reproducibility. Tate continues Dimmock’s operation on Poe a half-century later, as he adapts the Ultima Thule to bring Poe into the fold.

Allen Tate, “Our Cousin, Mr. Poe,” in Essays of Four Decades (Chicago: Swallow Press, 1968), 385.

On the use of daguerreotypes of Poe to explicate his character and biography, respectively, see William A. Pannapacker, “A Question of ‘Character’: Visual Images and the Nineteenth-Century Construction of Edgar Allan Poe,” Harvard Library Bulletin 7, no. 3 (1996): 9–24, and Kevin J. Hayes, “Poe, the Daguerreotype, and the Autobiographical Act,” Biography 25, no. 3 (2002): 477–92.

During the last decade of Poe’s life, which was the first decade of photography in the United States, Poe sat in front of the camera on six occasions , producing eight daguerreotypes. Each was named after the person or entity who purchased it or who received it as a gift or heirloom, except the Ultima Thule , which Sarah Helen Whitman named in allusion to Poe’s “Dream-Land.” Michael J. Deas, The Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe (Charlottesville: Univ ersity Press of Virginia, 1988) , 36 –38.

Tate, “Our Cousin, Mr. Poe,” 399.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” in Selected Writings, volume 3, 1935–1938, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2002), 104.

Thomas C. Carlson, “Biographical Warfare: Silent Film and the Public Image of Poe,” Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Cultures 52, no. 1 (1998/1999): 8.

Ibid., 7.

Ibid., 16.

Mary Ann Doane, The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 81.

Ibid., 104.

Doane, Emergence of Cinematic Time, 104.

Edgar Allan Poe, “A Chapter on Science and Art,” Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, and Monthly American Review, April 1840, 193.

Deas, Portraits and Daguerreotypes, 57.

Ibid., 58–60.

Luke Crafton, “The Purloined Portrait,” Follow the Stories: Omaha, Nebraska (2005), Antiques Roadshow, PBS.org, last modified March 27, 2006, accessed August 4, 2012, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/fts/omaha_200402A06.html.

Susan Jaffe Tane, owner of the largest private Poe collection and generous supporter of scholarship on Poe, bought the Players Club at Sotheby’s.

Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 103.

Ibid., 103.

Ibid., 104, 105, 101.

Ibid., 101–2.

Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, 1741–1930 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1958–1968), 470.

Rayford W. Logan, The Betrayal of the Negro from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson (New York: Collier Books, 1965).

Dickson D. Bruce Jr., Black American Writing from the Nadir: The Evolution of a Literary Tradition, 1877–1915 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 2.

George E. Woodberry, “Poe in New York,” Century Magazine (October 1894): 854.

Deas, Portraits and Daguerreotypes, 58.

Roland Barthes, Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill & Wang, 1988), 31.

Ibid., 21.

Ibid., 25, 26.

Ibid., 26.

Ibid., 31.

Thomas Dimmock, “Notes on Poe,” Century Magazine (June 1895): 315.

Ibid.

Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 106.

Dimmock, “Notes on Poe,” 316.

Ibid.

Ibid., 315.

Ibid.

Ibid., 316.

“Literature, #201,” Jewels in Her Crown: Treasures of Columbia University Libraries Special Collections, 2004, accessed August 4, 2012, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/eresources/exhibitions/treasures/html/201.html; Dimmock, “Notes on Poe,” 316.

Dimmock, “Notes on Poe,” 316.

Miriam Bratu Hansen, “Benjamin’s Aura,” Critical Inquiry 34 (2008): 336.

Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 109.

Ibid., 101–2.

Ibid., 103; Doane, Emergence of Cinematic Time, 93.

Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 103.

Fred Botting, Limits of Horror: Technology, Bodies, Gothic (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2008), 6.

See Michel Foucault, “What Is an Author?” in The Book History Reader, ed. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery (London: Routledge, 2002).

Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 105.

Ibid., 102.

Ibid., 102, 104.