Theo van Gogh’s Paris apartment was on the fourth floor of 54, rue Lepic, within walking distance of his office on boulevard Montmartre. It was a spacious apartment with rooms that opened onto each other over a single floor. Light flooded in from large windows and the walls were hung with his modern art collection, including many of the paintings that his brother had sent from Arles. On Sunday 23 December 1888, Theo spent the day at home with a young woman he knew from Holland, Johanna Bonger, the sister of his good friend Andries. Jo had recently joined her newly married brother in Paris.

In Amsterdam the previous year she had written in her diary: ‘Friday was a very emotional day. At two o’clock in the afternoon the doorbell went: [Theo] Van Gogh from Paris.’ Yet the meeting did not continue quite the way she had imagined:

I was pleased he was coming. I pictured myself talking to him about literature and art, I gave him a warm welcome – and then suddenly he started to declare his love for me. If it happened in a novel it would sound implausible – but it actually happened; after only three encounters, he wants to spend his whole life with me … It is quite inconceivable … but, I could not say ‘Yes’ to something like that, could I?1

Although Jo had given him a definite ‘no’ the year before in Amsterdam, Theo was unable to forget her. Then in December 1888, whether by design on her part or by chance, she bumped into Theo in Paris. They had not seen each other since he’d proposed and much had happened in the intervening months: thanks to his support of artists such as Monet and Gauguin, Theo was forging a reputation as a dealer of modern art in Paris. And now, far away from family constraints and conventions, their relationship rapidly blossomed.

On 21 December 1888, Theo van Gogh finished his day’s work at Boussod, Valadon et Cie. and walked home through the winter gloom. Emboldened by their renewed friendship, he proposed to Jo again and this time she accepted. He wrote to her parents and his mother asking for their blessing and posted the letters that very evening. The lovers spent the weekend in each other’s company as much as they could, blissfully unaware of the drama that was unfolding in Arles. If both families agreed, Jo would return to Amsterdam to prepare for the formal announcement of their engagement. They planned to marry as soon as they could, in April 1889. Being separated for even just a few hours was torment for the young couple, and in Paris they corresponded with one another, often several times a day. The letters between Theo and Jo detail a joyous love story, but also the day-by-day record of Van Gogh’s breakdown as the news arrived in Paris from Arles.2

Sunday 23 December was the first full day the young couple had had any time alone to discuss their future life together since Jo had accepted. She was overwhelmed by her happiness, and she wrote to Theo later from Amsterdam:

I’ve told our good news to a few close acquaintances. It’s strange talking about it – it sounds so banal, two people getting engaged – but when other people discuss it, I think: you really have absolutely no idea of what it means to us. We had wonderful times together in those few days, did we not? What I liked most was looking at the paintings – though better still in your room. That’s where I usually picture you – it was so peaceful, I felt closer to you than anywhere else.3

Theo’s mother and his sister Wil replied, offering their congratulations; and of course, given how close he was to his brother, it is likely that Theo had already written to Vincent, though no record of their correspondence about his marriage exists.4 This news was the culmination of months of longing, and it would have been hard for Theo to suppress his joy.

Monday was Christmas Eve – a particularly busy time at the gallery for Theo. Apart from advising clients on purchasing gifts of artwork, the annual accounts and stocktaking needed to be organised for the end of the year. Sometime during the morning an urgent message came for Theo at work, and later that day he wrote a desperate letter to his fiancée sharing his awful news:

My dearest,

I received sad news today, Vincent is gravely ill, I don’t know what’s wrong, but I shall have to go there as my presence is required … of course I cannot say when I’ll be back; it depends on the circumstances. Go home & I shall keep you informed … Oh may the suffering I dread be staved off.5

In her introduction to the compilation of their letters, Brief Happiness, Jo stated that Theo heard about the crisis in Arles in a telegram from Gauguin. The telegraph service between Paris and Arles was highly efficient: telegrams could be sent from the post office on place de la République, one of Arles’ main squares, and would be delivered within the hour. On 24 December 1888 the branch was operating its winter schedule and opened at 8 a.m.6 Yet at that hour of the morning even Gauguin was unaware of the dreadful events of the night before. In his autobiography he provided a rough timeline of Christmas Eve morning. He got up late, according to him – around 7.30 a.m. – walked across to the Yellow House, was arrested by the police, went up to see ‘the body’ and was duly released. Then a doctor and carriage were called, to take Vincent to hospital. Gauguin wouldn’t have had time to get to the post office to send Theo a telegram until mid-morning at the earliest. Later that afternoon he sent Theo a second telegram, reassuring him that all was not lost. Theo dashed off a short note to Jo at the post office: ‘I hope it is not as bad as I thought at first. He is very sick but he might still recover.’7

Finally, after a long day at work, Theo went to the Gare de Lyon to catch a train south. He had a welcome surprise: Jo, who was ill with a cold, had delayed her trip back to Amsterdam and, despite feeling unwell, had travelled across Paris to see off her fiancé at the station. Leaving at 9.20 p.m., Theo began the arduous journey to the city that he had only heard about through his brother’s letters – the very same journey Vincent had taken just ten months earlier. Given the urgency, it’s likely he caught the express train number 11, which took only first-class passengers and arrived in Arles at the earliest possible time.8 In the whirlwind of activity – taking emergency leave from work, packing his bags, seeking news from Arles and relaying news to Jo – Theo was probably protected from the full force of his emotions. As he sat on the train that Christmas Eve, rattling through the night, the fear and apprehension of what might greet him in Arles must have filled his thoughts.

Theo van Gogh arrived in Arles at 1:20 p.m. on Christmas Day 1880. Paul Gauguin most likely met him at the station. It was a sunny, crisp winter’s day – in any other circumstances, the perfect weather to see Arles.9

The town was exceptionally quiet. As they walked through the city along the banks of the Rhône, I imagine Gauguin carefully answering Theo’s questions about what had taken place little more than thirty-six hours before. Yet despite the desperate circumstances, Paul Gauguin and Theo van Gogh were only acquaintances, not friends. There was the financial arrangement between them that had enabled Gauguin to come to Arles in the first place. There was also the issue of Gauguin’s work: Theo was a dealer and Gauguin his client. It was a delicate situation for both men.

I wonder if Gauguin ever confronted Theo about the wisdom of supporting his own stay in Arles. It’s most likely that their discussion would have been formal and polite; despite the raw emotion on both sides, neither man could afford to alienate the other. Did Gauguin tell Theo exactly what had taken place between him and his brother – the desperate conversations, the threatening scenes, the anguished mind in turmoil?

In Paris, Theo had stature and clout, and Gauguin needed his patronage and his approval. Here in Arles, though, Theo badly needed Gauguin’s support. He had never been to Arles, didn’t know his way around or who to consult about Vincent’s situation. While Gauguin seems the most likely person to have accompanied Theo to the hospital, Gauguin refused to go inside with him to see the ailing Van Gogh. As he had said to the police the day before, ‘If he asks for me, tell him that I have left for Paris. The sight of me could be fatal to him.’10

On 26 December at 1.04 a.m. Theo took the overnight train back to Paris with Gauguin. For Theo, it had been an exhausting and stressful eleven hours in Arles.11 For Gauguin, it was the end of a peculiarly tumultuous few months. Once he was home Theo wrote to Jo about his trip to Paris.

He seemed to be all right for a few minutes when I was with him, but lapsed shortly afterwards into his brooding about philosophy & theology. It’s sad being there, because from time to time all his grief would well up inside & he would try to weep, but couldn’t. Poor fighter & poor, poor sufferer. Nothing can be done to relieve his anguish now, but it is deep & hard for him to bear. Had he just once found someone to whom he could pour his heart out, it might never have come to this. The prospect of losing my brother, who has meant so much to me & has become so much a part of me, made me realise what a terrible emptiness I would feel if he were no longer there … for the past few days he had been showing symptoms of that most dreadful illness, of madness … Will he remain insane? The doctors think it possible, but daren’t yet say for certain. It should be apparent in a few days’ time when he is rested; then we will see whether he is lucid again.12

In Arles, Theo had attended to his brother who had been placed with the other patients in the men’s ward. He then had a meeting with Dr Rey before going to see a couple of Vincent’s friends: the postman Joseph Roulin and the Protestant pastor, Reverend Salles, who was also one of the hospital’s chaplains.13 These two men, along with Dr Rey, would be Theo’s conduit to Vincent in the long months that he spent far away from his brother in Paris.

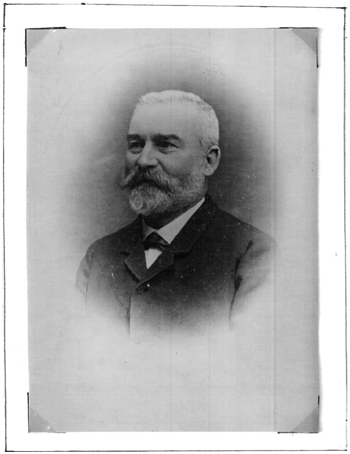

Reverend Frédéric Salles, Protestant Pastor of Arles, c.1890

Theo and Gauguin arrived back in Paris in the late afternoon of Wednesday 26 December.14 That same day at the hospital in Arles, Vincent had a visit from Joseph Roulin, who had promised Theo he would keep an eye on Vincent and report back. Later that evening he wrote with distressing news: ‘I am sorry to say that I think he is lost. Not only is his mind affected, but he is very weak and down-hearted. He recognised me but did not show any pleasure at seeing me and did not inquire about any member of my family or anyone he knows.’ Given the way Vincent had adopted the whole Roulin clan as a proxy family, this was especially alarming. He went on:

When I left him I told him that I would come back to see him; he replied that we would meet again in heaven, and from his manner I realised that he was praying. From what the concierge told me, I think that they are taking the necessary steps to have him placed in a mental hospital.15

Theo immediately wrote to Dr Rey, but there appears to be no foundation to the concierge’s comment that the paperwork to send Vincent to the asylum was already being prepared, although this was the standard procedure to commit a patient. Dr Rey’s main concern was medical: as Vincent himself had put it, he had lost a ‘very considerable amount of blood’16 and it was vital to build up his strength before any decision about his future could be made. His mental health, which seemed deeply unclear at this stage – was he suffering from temporary trauma and exhaustion, or from a more innate delusion for which there was no respite? – was a secondary consideration.

* * *

Just before his breakdown Vincent had been painting a series of portraits of Joseph Roulin’s wife Augustine, the most poignant of which he called La Berceuse. He chose to paint her at home.17 Still breastfeeding, she is shown holding a rope, which she uses to gently rock the cradle of her baby daughter, Marcelle. These paintings depict an embodiment of the ideal mother that features so prominently in the Christian Christmas tradition. An obsession with religion and religious imagery, for example the Virgin Mary and the betrayal of Christ at Gethsemane, preceded – and was linked to – Vincent’s mental crises. It was clearly hard for him to disassociate Augustine from this vision, and after she visited him in hospital on Thursday 27 December he had his second breakdown.

He’d begun to act erratically during her visit and, after she left, he became very agitated. Dr Rey was called immediately. Van Gogh later described what he remembered of this delirium:

and it seems that I sang then, I who can’t sing on other occasions, to be precise an old wet-nurse’s song while thinking of what the cradle-rocker sang as she rocked the sailors and whom I had sought in an arrangement of colours before falling ill.18

Later Dr Rey told Theo that Vincent had begun to deteriorate the day before her visit, on Wednesday 26 December, his behaviour becoming increasingly bizarre. Roulin updated Theo on 28 December, the day before the hospital committee was due to meet to discuss the options for current patients:

Today, Friday, I went to see him and wasn’t able to. The intern and the nurse told me that after my wife left he had a terrible breakdown. He had a very bad night and they were forced to put him in isolation. The intern told me that the doctor was waiting a few days before deciding whether to commit him to the asylum in Aix.19

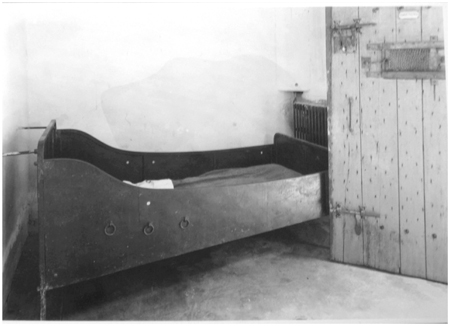

Vincent’s strange behaviour had resulted in him being placed for the first time in an isolation cell, known as the cabanon or hut. This small room, of just 10 square metres (110 square feet), was outside the main hospital building and was an emergency solution for patients who were a danger to themselves or others. There was no heating and in late December 1888 the weather was bitterly cold, with torrential rain once again flooding parts of the city. Placing a patient in the cabanon was only ever a temporary solution until they could be sent to the asylum. Alone in the cabanon, Vincent was constrained with leather straps that passed through rings on the side of the metal bed, which were then firmly attached to the wall and floor.

The cabanon at Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Esprit, Arles

Light came in through a small barred window high up on the wall above the bed and the patients were checked from time to time, via a small sliding hatch on the wooden door. Cold, damp, alone and deeply fragile, Vincent was traumatised. He later spoke about the experience: ‘Where can I go that’s worse than where I’ve already been twice – the isolation cell.’20 The conditions at the hospital were fairly basic, but they were nothing compared to the truly dire conditions in a nineteenth-century lunatic asylum.

Despite periods of lucidity after first being admitted to hospital, Vincent’s second breakdown within a few days led the doctors to conclude that he needed specialised care and they began the official process of interning him. If the paperwork was deemed to be in order, the town hall would authorise transport to the regional asylum in Aix-en-Provence, some 43 miles away. It would take a few days before all the formalities were complete.

To the Mayor of Arles, 29 December 1888

I have the honour of addressing you the enclosed certificate from Doctor Urpar, Chief Physician at the Hospital, stating that M. Vincent, who on the 23rd of the month cut off his ear with a razor, is suffering from a nervous breakdown. The care that the unfortunate individual has received in our establishment has not been able to bring him back to reason. I humbly request that you take the necessary measures to have him admitted to a special asylum.21

Once his superiors had made their decision, Dr Rey wrote to Theo:

His mental state appears to have worsened since Wednesday. The day before yesterday he went to lie down in another patient’s bed and would not leave it, despite my comments. In his nightshirt he chased the Sister on duty and absolutely forbids anyone at all to go near his bed. Yesterday he got up and went to wash in the coal-box. Yesterday I was forced to have him locked up in an isolation room. Today, my superior issued a certificate of mental disturbance, reporting general delirium and requesting specialised care in an asylum.22

Even though Dr Rey said nothing in his letter to suggest that Van Gogh’s life was in danger, strangely Theo feared that Vincent was dying. He wrote to Jo about his fears:

Dearest Jo, I cannot speak my mind like this to anyone else and I thank you for it. My dear mother knows no more than that he is ill and that his mind is confused. She is not aware that his life is in danger, but if it lasts for any length of time she will find out herself.23

I imagine Van Gogh angry and frustrated in the tiny little cell, imprisoned like a caged animal, and Dr Rey described to Theo Vincent’s reaction when he and the Reverend Salles visited him:

he told me that he wished to have as little as possible to do with me. He remembered, no doubt, that it was I who had had him locked up. I then assured him that I was his friend and that I wished to see him recovered soon. I did not hide his situation from him, and explained to him why he was in a room by himself.24

I wondered if Vincent was still attached to his bed by the leather straps when the two men entered the room. The paranoia and fear that Dr Rey described in his letter would be one of the recurring symptoms of Vincent’s breakdown. Dr Rey continued, ‘When I tried to get him to talk about the motive that drove him to cut off his ear, he replied that it was a purely personal matter.’25

The doctor then broached the delicate matter of what Theo wanted for Vincent: ‘At present, we are treating only his ear, and no aspect of his mental state. His wound is greatly improved and is not giving us any cause for concern. A few days ago, we issued a certificate of mental disturbance.’26 By this, Rey meant the certificate issued by Dr Delon, his superior. This was the obligatory first stage of the committal procedure. Placing someone in a psychiatric institution in France was a deliberately complex affair, to avoid any possible error. The second stage was the mayor’s formal acceptance that the patient was ‘suffering from mental alienation’. The paperwork to request a transfer to the regional asylum was then started. Meanwhile the mayor would ask the police to conduct an inquiry.27 This thorough and lengthy procedure could be stalled or delayed by any of the parties, if they felt fit. Dr Rey did make an alternative suggestion to Theo:

Would you like to have your brother in an asylum close to Paris? Do you have resources? If so, you may very well send him to look for one; his condition easily allows him to make the journey. The matter has not progressed so far that it could not be halted, and for the chief of police to suspend his report.

Without criticising the regional asylum, Dr Rey implies that it might be better to place Van Gogh in a private institution. The last sentence, that the process could be stopped at this stage, reaffirms the notion that once Vincent was placed in an asylum he wouldn’t be allowed out.28

Meanwhile, in Arles, anyone who hadn’t already heard the story of Vincent and his ear now knew all about it, as an account of the incident appeared in the newspaper Le Forum Républicain on Sunday 30 December. Vincent, who was known by sight in the city, was suddenly the subject of gossip all over town, and gradually mistruths about the artist began to circulate.

On Monday 31 December the hospital committee met again. It was presided over by the Mayor of Arles, Jacques Tardieu, along with two hospital administrators, Alfred Mistral and Honoré Minaud, and Dr Albert Delon.29 On New Year’s Eve the Reverend Salles wrote to update Theo:

I found him talking calmly and coherently. He is amazed and even indignant (which could be sufficient to start another attack) that he is kept shut up here, completely deprived of his liberty. He would like to leave the hospital and return home. ‘At the moment I feel capable of taking up my work again,’ he said, ‘why do they keep me here like a prisoner?’ … He would even have liked me to send you a telegram to make you come. When I left him he was very sad, and I was sorry I could do nothing to make his situation more bearable.30

Far away in Paris, with a wedding to plan and the gallery enjoying its busiest time of year, Theo must have felt powerless and distraught. The stress he was under is palpable in the tone of his letters to Jo. A round trip to Arles took almost three days. There was no way he could spare the time. Theo had to trust people he had met only once with the welfare of his beloved brother. Returning to live on his own in the Yellow House was no longer a feasible prospect for Vincent. There was only one place left: the asylum.

As always in a crisis, friends rallied round. In his letters to his fiancée, Theo mentions that three people had been particularly good to him: his future brother-in-law Andries Bonger was very attentive; the painter Edgar Degas came by regularly, having heard of what happened in Arles from his close friend, the dealer Alphonse Portier, who lived in the same building as Theo; and Gauguin also visited Theo, though how often is not clear, as he was staying with Schuffenecker on the other side of Paris.31 At the very least he must have been there on the day Theo heard from Dr Rey and Joseph Roulin, as he mentioned the incident concerning the coal-box to Émile Bernard, who later relayed it to others.

On New Year’s Eve, Theo heard back from his mother: ‘Oh Theo, what sorrow,’ she wrote:

Oh, the poor boy! I had hoped things were going well and thought he could quietly devote himself to his work! … Oh Theo, what will happen now, how will things turn out? From what I now hear something is missing or wrong in the little brain. Poor thing, I believe he was always ill, and what he and we have suffered are the consequences of it. Poor brother of Vincent, sweet, dearest Theo, you too have been very worried and troubled because of him, your great love, wasn’t it too heavy a burden, and now you’ve again done what you could … Oh Theo, must the year end with such a disaster?32