Theo’s brother is here for good, he is staying for at least three years to take a course of painting at Cormon’s studio. If I am not mistaken, I mentioned to you last summer what a strange life his brother was leading. He has no manners whatsoever. He is still at logger-heads with everyone. It really is a heavy burden for Theo to bear.

Andries Bonger to his parents, Paris, about 12 April 18861

In late February 1886 Vincent van Gogh arrived in Paris, attracted by the vibrant modern art scene in the city, to live with his younger brother, Theo, an art dealer. Turning up with no prior warning, Vincent sent a note to Theo’s office that began with the words, ‘Don’t be cross with me that I’ve come all of a sudden.’2 Van Gogh’s move to the centre of the contemporary art world was an inevitable step on a journey that had begun six years earlier, when he had decided to devote his life to art.3

* * *

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30 March 1853, to Reverend Theodorus van Gogh and his wife Anna Cornelia van Gogh (née Carbentus) at their parsonage in Zundert in the Netherlands. This new baby arrived exactly a year to the day after a stillborn male child, also called Vincent Willem.4 Both boys were named after the Reverend Van Gogh’s father.5 The pastor had followed his father’s calling, but art was the family profession – three of Van Gogh’s uncles were art dealers. There was a constant round of social visits between the relatives, but the six Van Gogh children lived considerably more modestly than their cousins. Obliged to make sacrifices to ensure that his children received the best possible education, Reverend Van Gogh left the family home in 1871 to take up a better living in another village. Life in Zundert had been a calm, idyllic time for all the family. While recovering from his first breakdown many years later, Vincent’s thoughts turned back to this childhood home: ‘I again saw each room in the house at Zundert, each path, each plant in the garden, the views round about.’6

Through their close-knit family network, the children met suitors and found work. The family were close to their Uncle ’Cent (Vincent), who, with no children of his own, had always taken a particular interest in his nieces and nephews. He was a partner in the Goupil & Cie. gallery – one of the most prominent international art dealers in Paris – which catered to the emerging upper middle class and specialised in modern works by painters such as Corot and others of the Barbizon School. He arranged that sixteen-year-old Vincent should start as an apprentice in The Hague branch of the firm, and within four years he was promoted to the London office. That same year, 1873, Van Gogh’s younger brother, Theo, joined Goupil in Brussels. The brothers were extremely close and shared a passion for art. At the start of their working lives, it seemed as if both men were destined to be art dealers; but where Theo thrived, rising to become manager of one of the prestigious Paris branches, Vincent was not remotely suited to the convention and rigour of the business world.

Vincent van Gogh, aged eighteen

Described by his contemporaries as intense, peevish and quick to anger, Vincent was often the subject of his friends’ jokes: ‘Van Gogh provoked laughter repeatedly by his attitude and behaviour – for everything he did and thought and felt … when he laughed, he did so heartily and with gusto, and his whole face brightened.’7 Vincent was unfailingly generous, profoundly kind to others and inspired great loyalty; but he was also a man of extremes. While working at Goupil’s in London, he had become increasingly involved in an evangelical form of Protestantism. This interest soon became an all-consuming passion, and after transferring to Goupil’s Parisian office in 1875, he was dismissed in April 1876. Vincent explained the situation to Theo:

When an apple is ripe, all it takes is a gentle breeze to make it fall from the tree, it’s also like that here. I’ve certainly done things that were in some way very wrong, and so have little to say … so far I’m really rather in the dark about what I should do.8

He returned to London to work as an assistant schoolmaster and began lay preaching at weekends. Over the Christmas holidays he told his parents he wished to become a pastor, insisting that the Church was his true calling. However, his family persuaded Vincent to return for good and found him a job in a bookshop in Holland. As Vincent hadn’t finished his schooling, this new plan would mean at least seven long years of study. But even this could not dissuade him. In May 1877 he moved to Amsterdam where he began the preparation for his theological studies, but he didn’t stay long. During the summer of the following year he started training as an evangelist in Belgium, but disappointingly was not offered a job at the end of the three-month trial period. Finally in January 1879, thanks to family connections, Vincent obtained a post as a trainee pastor. He would begin his first post as a lay minister amongst the working-class miners of the Borinage, in Belgium.

Van Gogh threw himself into this new world with total conviction. He took his pastoral duties very seriously, tending to the sick and destitute parishioners personally. Wishing to better experience the life of the poor and emulate a Christ-like existence, Vincent gave away all his unnecessary possessions and clothes, refused to sleep in a bed, and spent hours working hard on his sermons. Scared by this eccentric and extreme behaviour, the parish elders decided Van Gogh was not suited to the life of a pastor and by July he had been dismissed, barely managing to complete the six-month probationary period.

If his professional life was fraught, his love life was possibly worse still. He had a series of relationships, each more disastrous than the last. With no sense of restraint, Van Gogh would pursue the object of his affections relentlessly, with an unequal passionate intensity, completely unaware that his feelings were not reciprocated, nor even welcome.

In 1881 Van Gogh decided he was in love with his recently widowed first cousin, Kee Vos, and proposed marriage. In addition to the manifest unsuitability of marrying such a close relative, Kee was not in love with him and had no wish to remarry. In an effort to win her over he turned up at his uncle and aunt’s house in Amsterdam one night while they were having dinner, demanding to see her. When he was refused entry, he thrust his hand over a lamp, and refused to remove it from the open flame, begging her dumbfounded parents to let him see her even if it was only for as long as he could hold his hand over the flame. Melodramatics aside, this sort of behaviour underscored the impression the wider Van Gogh family held of him – Vincent was more than odd, he was mad.

During Vincent’s early adulthood, his mental health was a constant source of anguish to his parents and was evoked frequently in their correspondence. As he moved into his twenties, his family did what they could to help him find his path in life, but his eccentricities only became more entrenched. His father wrote to his favourite son in 1880: ‘Vincent is still here. But oh, it is a struggle and nothing else … Oh, Theo, if only some light would shine on that distressing darkness of Vincent.’9

In the late nineteenth century the study of the mind was still in its infancy. Private institutions to house the mentally ill did exist, but were more akin to holding pens.10 For anyone with an emotionally disturbed child, the only option was a state lunatic asylum, and few people survived many years in one of those. In 1880, after a series of particularly distressing events, Reverend Van Gogh and his wife took steps to place twenty-seven-year-old Vincent in an institution in Belgium, but the family, with strong objections from Vincent, was unable, or unwilling, to force the issue and he was never committed.11 Van Gogh recalled this period in a letter to Theo the following year: ‘It causes me much sorrow and grief but I refuse to accept that a father is right who curses his son and (think of last year) wants to send him to a madhouse (which I naturally opposed with all my might).’12 After the drama in Arles in December 1888, recalling the professional appraisal of her son given eight years earlier, Anna van Gogh wrote to Theo, ‘there is something missing or wrong with that little brain … Poor thing, I believe he’s always been ill.’13 There were many signs that Van Gogh had psychiatric problems. Alas, in the family these were not confined exclusively to Vincent. It is impossible to know whether he had a hereditary disorder, but there are indications that there was a family history of mental illness, which Vincent later mentioned to one of his doctors.14 Of the six children born to the Reverend Van Gogh and his wife, two would commit suicide and two would die in asylums, though Theo was diagnosed with syphilis of the brain.15

Throughout his life, Van Gogh was attracted to the destitute, the suffering, those in desperate need, certain he was the only person who could save them. In January 1882 he met Sien Hoornik, an ex-prostitute, pregnant with another man’s child and three years older than Van Gogh.16 By July Sien, her new baby and her five-year-old daughter moved in with Van Gogh. This was the first time Vincent had lived with a woman and for a time it worked well. Van Gogh was happy to have some semblance of an idealised family life and Sien became his model. They separated in September 1883. Vincent explained his feelings to Theo: ‘From the beginning with her, it was a question of all or nothing when it came to helping. I couldn’t give her money to live on her own before, I had to take her in if I was to do anything of use to help her. And in my view the proper course would have been to marry her and take her to Drenthe. But, I admit, neither she herself nor circumstances allow it.’17

Throughout the first half of the 1880s, as his parents despaired over his constantly erratic behaviour, Vincent was intermittently estranged from his family. Like many young men, he was desperate to live independently but, unable to survive without his parents’ or Theo’s financial support, from time to time he was forced to return home.

Over the summer of 1884, he got to know Margot Begemann who lived next door to the Van Gogh family in Neunen. In July, Margot took over his mother’s sewing class when she was laid low after breaking her leg, and began a relationship with Vincent. Both families strongly disapproved of the liaison and Vincent explained to Theo on 16 September, ‘Miss Begemann has taken poison – in a moment of despair, when she’d spoken to her family and people spoke ill of her and me, and she became so upset that she did it, in my view, in a moment of definite mania.’18 Vincent’s reaction to her attempted suicide was to feel he should marry her, yet he complained in the same letter that her family had requested that he should wait two years.

* * *

Quite unexpectedly, on 26 March 1885, four days before Vincent’s thirty-second birthday, the Reverend Van Gogh died. Notwithstanding the often fractious nature of their relationship, Vincent and his family were united in mourning. The truce was only temporary, though, and after an argument with his sister Anna, Vincent left the family home in May 1885 – this time for good.

Van Gogh had dabbled in drawing and painting since he was a child, and since the mid-1880s he was working more seriously. Around this time he executed his first major work, The Potato Eaters. The canvas is unrelentingly harsh: a social commentary on the life and dire conditions of the Dutch peasant community. The rough living conditions of the workers, gathered together to eat the most lowly and basic meal, are accentuated by the subdued palette. With its dark interior and sombre tones, the painting is modern in subject matter, showing the working class in the brutal reality of their hand-to-mouth existence. Although he was not entirely satisfied with the work, Van Gogh knew he had achieved something. When he met Émile Bernard in Paris a year later, he proudly showed him The Potato Eaters, though Bernard remarked that he found it ‘frightening’.19

Much though the idea of sharing an apartment with Theo had been in the offing for a while, his sudden arrival in Paris was a surprise. Yet this impetuous behaviour was – if disorientating for Theo – entirely in Vincent’s nature. At the time, twenty-eight-year-old Theo was working as manager at Boussod, Valadon et Cie., the renamed Goupil & Cie., at 19, boulevard Montmartre.

In late February 1886, desperate to be elsewhere, Vincent left Belgium, not even paying his bills, as he later confessed in June 1888: ‘Wasn’t I forced to do the same thing in order to come to Paris? And although I suffered the loss of many things then, it can’t be done otherwise in cases like that, and it’s better to go forward anyway than to go on being depressed.’20

He began to study drawing and painting at the studio of the artist Fernand Cormon, finding new friends among its pupils: Émile Bernard, the Australian artist John Peter Russell, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.21 Yet he didn’t stay long at the art school:

I was in Cormon’s studio for three or four months but did not find that as useful as I had expected it to be. It may be my fault however, anyhow I left there … and [ever] since I have worked alone, and fancy that I feel more my own self … I am not an adventurer by choice but by fate and feeling nowhere so much myself a stranger as in my family and country.22

Since the early 1880s Theo had been providing Vincent with a monthly stipend from his own salary, supplementing the allowance he received from his parents. Theo loved his brother dearly and wished to help him live the life he chose, but he also felt a moral obligation to help Vincent be the person – and the artist – he had the potential to be.23 Theo’s meticulous account books demonstrate his extreme generosity: he gave an estimated 14½ per cent of his salary to his brother to fund his life as a painter.24 This expenditure increased substantially after Vincent moved to Arles.

In addition to Vincent’s own painter friends, Theo, as a well-known dealer, was his brother’s conduit into the Parisian art scene. Vincent met and swapped paintings with a few of his contemporaries. The brothers saw this arrangement as an investment they were making in the future of modern art; Vincent, financed by Theo, contributed his artwork to the deal and through the exchange of paintings. For a while it worked well; the brothers built up a sizeable collection of contemporary works and Japanese prints, which, with Vincent’s paintings, are now part of the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

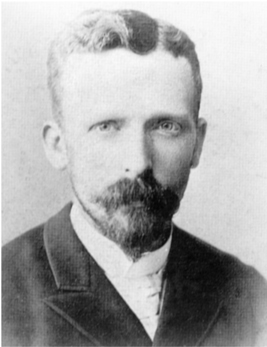

Theo van Gogh, c.1887

The relationship between the brothers was very close. Devoted to his older sibling, Theo not only financed Vincent’s life, but also supported and regularly defended him. Without that financial and emotional investment, Vincent’s achievements would not have been possible. We know Van Gogh’s work today thanks to his remarkable brother (and later Theo’s widow, Johanna Bonger), who preserved Vincent’s letters, drawings and paintings for posterity. Their relationship has become an essential part of Vincent’s life story: the genius of Van Gogh, aided and abetted by the selfless generosity of Theo. Yet this is a sugar-coated portrayal. Living together in Paris was not without its strains; the two men argued, and occasionally these rows were nasty. In early 1887 they reached crisis point:

Vincent continues his studies and he works with talent. But it is a pity that he has so much difficulty with his character, for in the long run it is quite impossible to get on with him. When he came here last year he was difficult, it is true, but I thought I could see some progress. But now he is his old self again and he won’t listen to reason. That does not make it too pleasant here and I hope for improvement. It will come, but it is a pity for him, for if we had worked together it would have been better for both of us.25

A few days after writing this letter, Theo began seriously to question his arrangement with Vincent, and wrote to his sister Willemien about it:

I have often asked myself whether it was not wrong always to help him and I have often been on the verge of letting him muddle along by himself. After getting your letter I have seriously thought about it and I feel that in the circumstances I cannot do anything but continue … You should not think either that the money side worries me most. It is mostly the idea that we sympathise so little any more. There was a time when I loved Vincent a lot and he was my best friend but that is over now.26

Vincent had moved his life and work wholesale into Theo’s space, transforming the apartment into an artist’s studio. His irascibility and erratic behaviour compounded the issue. The story of the brothers’ perfect relationship has been cultivated over the years, ever since Theo’s widow edited the first edition of the letters, published in 1914. With Jo leaving certain details out of her book, the business of editing Vincent’s life story began.

Van Gogh had initially come to Paris to learn from modern masters, particularly the Impressionists – the group at the forefront of contemporary art – but by the time he arrived the movement had run its course and the Impressionist exhibition of 1886 was to be its eighth and final show. Impressionism, with its bright palette capturing the middle class at play, had been a radical departure from the academic paintings that still dictated public taste in the 1880s. Yet younger artists were beginning to move on, embracing new ideas like Symbolism. Strongly influenced by Japanese prints, these painters would go further, using pure colour in a vibrant, raw fashion to illustrate a new side of nineteenth-century life: laundresses, prostitutes and peasants, subject matter which suited Vincent van Gogh perfectly.

While in Paris, he tried to find new outlets for his work, showing some of his paintings including his Sunflowers at a restaurant called Le Tambourin.27 Vincent had a brief affair with the owner, and in 1887 he painted Portrait of Agostina Segatori, showing her sitting at one of her tambourine-inspired tables.

In November and December 1887, frustrated by the few galleries that were willing to show modern art, Van Gogh organised a group show at the restaurant known as Le Petit Chalet.28 One of the artists who saw the exhibition was Paul Gauguin, recently returned from a painting trip to Martinique. The show was not the success Van Gogh had hoped it might be: just two paintings were sold, and Vincent’s aspiration to create a new brotherhood of like-minded painters in the capital appeared foolish. To Van Gogh, it seemed that everyone in the Paris art world was thriving and, after two years, he had barely sold any paintings. Disillusioned and depressed with his life in Paris, he was now desperate to leave and start afresh somewhere new. He revived an idea he had first mooted in 1886: to go to the south of France.

Living in the metropolis had made him physically unwell, as Van Gogh told his brother within days of arriving in Arles. ‘At times it seems to me that my blood is more or less ready to start circulating again, which wasn’t the case lately in Paris, I really couldn’t stand it anymore.’29 The French capital, with its sophisticated social circles and endless noise, was the antithesis of what Vincent sought in life. Working in Paris had taught him the importance of contrasting colour and, from the Japanese prints he collected with Theo, he had learned to use unconventional perspectives and compositions. With these new ideas at his disposal, he turned back to the subject matter of his early canvases from Holland: landscapes and portraits of simple working people. To find what he was looking for, he needed to leave Paris.

* * *

No one knows exactly why Van Gogh decided on Arles. Marseille would have seemed a more obvious choice. Not only was it the last home of the painter Adolphe Monticelli, whom Van Gogh particularly admired, but it was also the departure point for ships to Japan, which he hoped to visit one day.30 Yet despite mentioning in his letters his intention of going there, Vincent never actually visited Marseille. Perhaps the bustling port was simply too big and noisy, the very thing he was trying to avoid. Given that Vincent’s reasons for choosing Arles in particular remain hazy, there has been plenty of speculation: was he in search of the famed light of the south? A new subject matter? Or was he simply looking to escape the capital? Women are usually mentioned as a possible reason, especially given that the ‘Arlésiennes’ – the women of Arles – were famed for their beauty throughout France.31 Degas had been to the city on a painting trip as a young man, and Toulouse-Lautrec – a fellow pupil of the Atelier Cormon – might well have suggested it to Vincent as a relatively cheap place to stay.32 Although Vincent had considered leaving for warmer climes as early as 1886, his journey south on 19 February 1888 seems to have been a spur of the moment decision.

On the day of his departure, Theo came to see him off from the station. On taking the No. 13 express train that left at 9.40 p.m., it would take Vincent a night and a day to get to Provence.33 While his train rattled through the flat landscape around Paris, Theo returned alone to the apartment they had shared at 54, rue Lepic. Pushing open the door, he turned on the gas lamps and intense colour flooded the rooms from the dozens of vibrant paintings that had been hung by his brother a few hours before. Vincent’s presence was everywhere.34