In late November or early December, as the days get shorter and the first frosts appear on the fields, Provence suddenly becomes a hive of activity. The olive harvest begins. In late 1889, Van Gogh began painting strange twisted trunks emblematic of the region’s olive groves. Pruned so that ‘a swallow can pass through the branches’, olive trees are an integral part of the Provençal landscape. The harvest is labour-intensive and very physical – 11 to 13 lbs of olives are required to make a litre of oil – but it is a highly satisfying winter ritual that has remained unchanged for thousands of years since ancient times. Although many use rakes and nets, I prefer to pick olives by hand, carefully and methodically moving through the branches to gather the fruit. It may appear as if there is nothing left on the branches when a gust of wind will blow, suddenly revealing another cache of luscious green pearls, like tiny bird’s eggs hiding among the silver leaves. A single olive is almost worthless, but when put together with hundreds of others it makes the liquid gold that is olive oil.

There are a lot of similarities between the harvest and the way I undertook my research for this book. Van Gogh’s Ear contains some important discoveries – about the ear, ‘Rachel’ and the petition – but also lots of tiny, seemingly inconsequential details that together reveal a more nuanced story of Van Gogh in Arles. It has been a slow, methodical process, working through the archives, looking at the story from every angle, relentlessly gathering little pieces of information from every source I had at my disposal, including Vincent’s paintings.

When I started this project my objective was to understand a small episode in Vincent’s life – one that defines him for the general public and is an essential part of the Van Gogh myth. There is a certain irony that Irving Stone, the very person whose papers helped answer my initial question, was also responsible for shaping that legend. The previous Head of Collections at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam wrote, ‘More than any other book Lust for Life has been instrumental in generating the prevailing myth of Vincent van Gogh.’1 Lust for Life is a romanticised and fictionalised version of his life which has entered people’s consciousness and over time become assumed fact. I realise now that for many years my perception of Vincent barely deviated from the character Irving Stone had created and Hollywood had amplified: an ill-kempt, lusty drunkard, a man whose creativity was fuelled by women, alcohol and madness. I had been happy to take received views of that fateful night of 23 December 1888 at face value, rather than trying to understand his mental state or what drove him to his truly spectacular act of self-harm. I interpreted his work through a very narrow telescope, blinded by the bright, flashy colours of his paintings and immunised by the constant use of these pictures. I fell for the image that great fame and unsurpassed popularity had bestowed upon Van Gogh – the legend of Vincent – the painter who was ‘mad’.

When I started this investigation I had not looked properly at Vincent van Gogh’s paintings for several decades, somewhat snobbishly because he was so popular. This popularity continues to travel far beyond the confines of the art world. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam receives more than 1.6 million visitors annually, making it one of the top ten most visited museums in the world and the only establishment on this list devoted to the life of a single artist. This Van Gogh is a guaranteed money-spinner (a friend recently gave me a pair of socks showing Vincent’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe). Yet all the fridge magnets, tea towels, umbrellas and notepads have done him great disservice: over-familiarity has in some ways weakened the impact of his imagery and obscured who he was and what motivated him to create.

Now I look at him very differently. Deeper knowledge has led to true appreciation and respect. I also look at Arles with fresh eyes now, seeing the people and landscape through Vincent’s sharp focus. I had no idea how I would become captivated by his world and the people who inhabited it. At first, simply names on a page in nineteenth-century script that I could barely decipher, they have gradually become real people and characters in the story. The faces caught on canvas more than a century ago are now so familiar to me it is as if I know them personally. These people weren’t random individuals who lived in a small French town; these were people he chose to paint because they meant something to him.

Van Gogh and his work are almost always judged through the prism of his madness. Yet to categorise his work in this way is very reductive, the truth is infinitely more nuanced. Van Gogh had serious psychiatric problems, there is no doubt, but he wasn’t manic all the time. His form of mental illness, with crises followed by periods of lucidity, had ramifications for his painting. Many of his works are masterpieces, but not all. As he acknowledged to Theo, Vincent was acutely aware of this. After finishing what he considered to be one of his best works, Almond Blossom, the next day he painted ‘like a brute’, distressed by being unable to control the impact his mental health had on his creative ability. With little to no treatment for mental illness in the nineteenth century, it is all the more remarkable that Van Gogh was able to produce so much work.

It is much easier to fit the story around the legend than to unravel the truth. If madness has long influenced our perception of his art, it is also through the paroxysm of madness that we have looked at his life. But, I have come to realise since I started this investigation, my simplistic images of Van Gogh and his madness are no longer valid. Vincent’s creativity reached its apogee in spite of his poor mental health not simply because of it.

The petition was never the work of a whole town up in arms and eager to chase a mentally ill man out of house and home. Rather it was the doing of two cronies who conspired together and exploited their contacts, preying on the justified fears of a small neighbourhood. Vincent van Gogh was never involuntarily committed; if he truly had posed a threat to the population the police would have forced the issue. He went calmly to an asylum and of his own free will. Gauguin was not a coward who had lied about what had happened in Arles and run back to Paris as fast as he could. Rather Gauguin found himself sharing the Yellow House with a man he barely knew, in the midst of a very dramatic breakdown so unfathomable that Gauguin recorded the blow-by-blow details in his notebook. There was little he could do to resolve the situation. Traumatised by probably being threatened with a razor in the park, Gauguin abandoned Vincent and his dream of a studio in the south – a lesser man would have left much earlier.

All of these points have been misinterpreted. The greatest distortion has been to do with the injury itself. Thanks to the discovery of Dr Rey’s drawing, long forgotten in an American archive, it is now possible to finally understand what Vincent did. Taking a cut-throat razor and slicing off part of your anatomy, whilst watching yourself in the mirror, is hard to envisage without shuddering. The ensuing gory scene, with Vincent in crisis, desperately ripping up sheets and trying to staunch the bleeding with towels, suddenly becomes all too real.

Van Gogh was overly sensitive – and at times irrational. But behind his seemingly impulsive behaviour, there was always an ill-conceived logic, never more so than on the night he cut off his ear. Rather than a completely random act of self-harm, his behaviour on 23 December 1888 – cutting his ear, washing it, wrapping it in a newspaper and taking it across town – was both deliberate and conscious. ‘Rachel’ wasn’t a prostitute as I had first thought. ‘Rachel’, or rather Gabrielle, was a young, vulnerable woman who worked hard to earn her wage. Van Gogh had carefully observed her as she went about her business: working through the night cleaning in the lowliest of places – a brothel. With her large visible scar, Gabrielle touched Vincent profoundly. Just as he had given his clothes away and slept on the floor as a young trainee pastor, just as he would commit suicide in part because he couldn’t bear to be a burden on his brother, Vincent took his ear that night not to scare or frighten Gabrielle but to bring succour. It may well have been seen as irrational and even frightening behaviour by the girl at the door of the House of Tolerance no. 1 on the rue Bout d’Arles, but for Vincent it was a personal, intimate gift, meant to alleviate what he perceived as her suffering. This singular act tells us so much that has been overlooked about Van Gogh: it was altruistic – the behaviour of a thoughtful, sensitive, and extremely empathetic man. Van Gogh becomes ‘Monsieur Vincent,’ a more sympathetic individual and the man whom the Ginoux, the Roulins and some of the other people of place Lamartine knew and appreciated.

Now, so many years later, I realise that practically everything I thought I knew about Vincent van Gogh in Arles when I set off on this adventure has turned out not to be true. Vincent had moments of deep crisis, but as his paintings, friendships and letters illustrate, despite his personal woes, he was far more than the sum of his torments and he never stopped creating. The world is far richer for it.

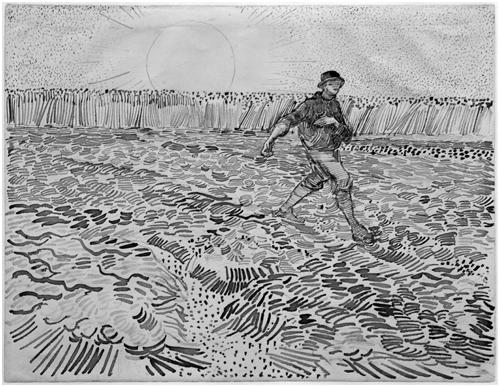

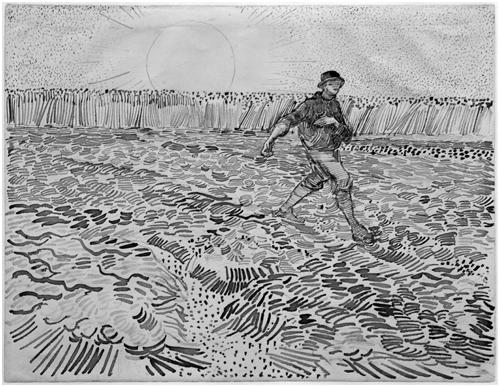

The Sower, Arles, 1888