Ageographical treatise from the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), Taengniji (Ecological Guide to Korea) outlines the requirements for identifying an ideal site for human habitation. A propitious site, it says, is one with excellent topography, ecology, wholesomeness, and hills and waters. Topography refers to the layout of the surrounding mountains and rivers; ecology to the things that originate from the ground; wholesomeness to the character of the local inhabitants; and hills and waters to the area’s scenic beauty. Of these four factors, three are natural phenomena directly related to the earth. This reflects the extent to which Koreans believed nature influenced the desirability of human habitation; indeed, Korea’s traditional architecture is meaningless in isolation from nature.

Although the practice of geomancy that Koreans call pungsu was introduced to Korea from China, where it originated under the name feng shui, it is actually in Korea, rather than in China or Japan, that its influence has been most evident. Mountains and rivers are the most important elements in pungsu. Mountains are needed for harnessing the wind, while rivers constitute sources of water. According to the East Asian perspective, nature is a world of abundant energy, or gi (often known in the West by its Chinese pronunciation, qi), that is constantly moving and changing. The wind transports the energy of the sky to the earth, while water carries the energy of the earth. Thus, a terrain with a proper arrangement of mountains and rivers is the most effective means of harnessing the energy of nature. A site with an abundance of natural energy is propitious, as it is believed that this energy will flow into the people living in a house built there.

Changdeokgung Palace is renowned for its design, which defers to the topography of its terrain.

NATURE: THE MOST FUNDAMENTAL INFLUENCE

The first and most important step in traditional Korean architecture, selecting a building site, involves properly interpreting the topography of the land. Ultimately, the most highly sought architectural sites were those known as baesan imsu, a term describing a setting with a high mountain at the rear to block the wind and a wide field in front with a river flowing through it. Such an area held promises of abundance.

Once the site was selected, the ground was leveled and prepared for the construction of the building. At this stage, the most important factor was determining the direction the building should face. The modern preference for a southern orientation was not an absolute rule. What the building would look out upon was often more important, indicating that psychological perspectives could take precedence over functional considerations. The scene over which a building looked out was called the andae. This was most often a mountain, because mountains are the only natural elements considered to be unchanging and everlasting.

Hahoe Village, with mountains to the north and a river to the south, demonstrates the baesan imsu principle.

The orientation of a village and individual houses can vary according to the andae involved. For example, in the Andong hometown of the renowned Neo-Confucian scholar Yi Hwang (Toegye), all the houses face west toward Mt. Dosan, an especially auspicious andae. In the famous Hahoe Village, however, where many mountain peaks face different directions, various villagers adopted different mountains from the surrounding landscape for their andae, and oriented their houses accordingly. As a result, the houses face in every direction—north, south, east, and west, according to their respective andae—giving the village a somewhat disorderly appearance. There exits, however, a very strict—albeit not readily apparent—order, whereby the setting of a building and its orientation are determined by various elements in its natural surroundings.

Why did pungsu exert such a powerful influence over the selection of building sites and the placement of structures in Korea? The Korean peninsula, which is covered with countless mountains and rivers, boasts a natural environment particularly well-suited to the principles of pungsu. It is almost as if the concept of pungsu were created as a means of interpreting the topography of Korea.

Hahoe Village: each house faces in a different direction according to its particular andae.

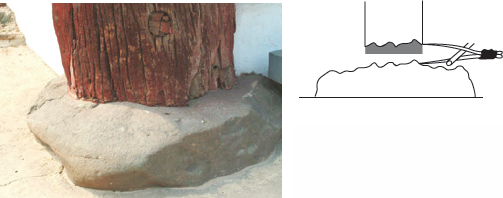

PRESERVING THE SPIRIT OF WOOD AND STONE

After deciding on a building site and orientation, the next step involves laying the foundations and erecting the supporting pillars. For the foundation, stones from stream beds were brought to the building site. Stones were not dressed but laid on the ground in their natural state, with their irregular surfaces intact. In order to secure a wooden pillar on top of a foundation stone, the base of the pillar had to be carved to match the irregular surface of the foundation stone. For this process, called geurengijil, a specially designed tool was used to draw the curves onto the base of a pillar, which was then carved with an adze. When the carved wooden base was placed on top of the stone, the two pieces would fit together like meshed gears, locking into each other in such a way that the wood and stone became one. Through this difficult and painstaking method, called deombeong jucho, the foundation stones and pillars were laid and erected in such a manner that the natural form of the materials was preserved.

At first glance, this may seem a rather primitive method. In fact, it is based on scientific principles. To place a wooden pillar on top of a stone is easier said than done. The base of a wooden pillar rots easily due to rainwater running down the column and gathering at its footing. To avoid this problem, it is necessary to raise the foundation stone above ground level. In addition, no connecting devices or adhesives can be used between the pillar and the stone because moisture will eventually creep in through the cracks and cause the wood to rot. Accordingly, the only alternative is to position the wooden pillar directly on the foundation stone. In this case, however, any horizontal force, such as earth tremor, a strong wind or a shift in structural load, would cause the pillar to slip off the stone and fall. The only method of construction that can effectively overcome these factors is the deombeong jucho method mentioned earlier. Because the irregular surfaces of the stone and wood lock together like meshed gears, the resulting framework is capable of withstanding even horizontal forces.

The geurengijil technique is used to mark the base of the pillar so that it can be carved to match the contours of its foundation stone.

All the structural pillars placed atop foundation stones are made of wood. Wood is one of the few architectural materials that comes from a living organism; because of its organic nature, it is very difficult and complex to handle. Unlike earth or bricks, wood must be allowed to breathe, can rot from moisture, and is prone to warping. Carpenters who build houses from wood need to understand the nature of this material. For example, wood from trees that have grown on the southern slope of a mountain should be used on the southern face of a house. The same principle applies to trees that have grown on northern slopes; they should be used for the rear, or shaded side, of the house. This is because wood performs best under conditions similar to its original environment.

Wooden columns on foundation stones at Jongmyo Shrine

The complex wooden structure of a palace roof

Pillars and girders, which bear significant structural loads, should be made from trees that have grown along the timberline. Only trees that have survived the harsh winds high atop a mountain ridge are resilient and sturdy enough to be used for pillars and girders. In contrast, trees that grew in humid valleys with mild temperatures should be used for walls or decorative applications, because their wood is pliable and workable. In order to exploit the ultimate potential of wood, it is necessary to know about the tree’s original environment, to such an extent that it was said in the past that expert carpenters did not acquire wood but rather a mountain. The carpenters responsible for building Korea’s royal palaces selected a mountain several years before the start of construction and examined the characteristics of the trees from various areas on it before deciding what wood from which tree would be used for each part of the building.

In Korea there is a shortage of thick, straight pine trees. Most pines are thin and crooked. Their bent timber has always been a problem for carpenters. If crooked pines are forcibly straightened out, they become too thin to be used for pillars or any upright elements. The ideal solution was to use the crooked wood in its natural state. On the exterior, this could appear crude and unattractive, but this method brought exceptional structural advantages. Girders and other horizontal elements always have to bear vertical loads from the roof. In extreme cases, when girders cannot withstand downbearing loads, they can collapse. But if wood that is already curved upward is used, there is no danger of it bending downward and breaking under pressure. Furthermore, from a visual perspective, an upward curving wood girder gives an appearance of stability. For this structural reason, wood that curved upward was used for girders and crossbeams in Korean traditional architecture. What began as a functional concept evolved into a notion of aesthetic beauty. Not straight but curved; not fine but coarse—it is this dynamic sense of aesthetics that created the beauty of traditional Korean architecture.

Daeungjeon at Cheongnyongsa Temple in Anseong is a textbook example of the number of ways in which curved wood can be used in a building. It contains not a single straight column in any of its four elevations. All columns are crooked and of noticeably different thickness at the top and bottom. Logically, it seems the building should topple over at any minute. However, this structure has been standing firm for over 200 years. The carpenters who built it knew the character of the wood they were using and used it with confidence. In Manseru Pavilion at Seonunsa Temple in Gochang, the crossbeams are all made of beautifully curved wood. Some were even made by joining two pieces of wood together. The interior, with all its twisted girders exposed, has no sense of coziness; rather, it projects an elemental, dynamic feel. Here, we see the application of a different sense of building aesthetics. According to the philosophy of Lao Tzu, who took nature as his model for humanity, “Those things which are finished seem to be unfinished, those things which are straight seem to be bent, and those things which are delicate seem to be clumsy.” Such is nature. And so, too, is the appearance of Korea’s traditional architecture.

Daeungjeon, Cheongnyongsa Temple: curved wood has been used in its natural state.

COPING WITH THE ENVIRONMENT

The Korean peninsula has four very distinct seasons. The coexistence of harsh, cold winters and humid, hot summers creates very difficult natural conditions for coping with architecturally. Indeed, designing a house that can retain heat during the winter as well as keep cool in the summer requires significant expertise and innovation. Korea, furthermore, receives heavy rain and snow, necessitating strong, high-pitched roofs. A strong roof creates a heavy load due to its thick and sturdy crossbeams and columns. Of all the weather conditions in the world, perhaps the most challenging to accommodate in terms of architectural design is the temperate monsoonal climate of the Korean peninsula.

The most exceptional feature of traditional Korean architecture is the integration of ondol (heated stone floor) and maru (wooden floor). Ondol is an under-floor heating system that was developed to provide heat during winter, whereas maru is a wooden floor designed to keep interiors cool, especially in humid weather. Ondol and maru, obviously, have opposing functions. Because an ondol floor is heated via underfloor flues, it must be built close to the ground in order to minimize heat loss. A maru, on the other hand, must be elevated off the ground in order to reduce humidity. Combining two such very different flooring systems at different heights in one particular building is no simple feat. After much trial and error, however, the two were successfully integrated, as can be seen in a hanok, the essence of Korean traditional architecture.

Unheated wooden maru (left) and heated ondol (right) floors

Partially heated floor systems, called kang, exist in northern regions of China, but only in Korean architecture are heated stone floors and wooden floors combined in the same building, revealing an advanced level of technology and expertise in overcoming extremes of both hot and cold.

Korea receives high rainfall, contributing to its success in rice farming. In the past, however, before the advent of synthetic waterproofing materials, building a leakproof roof constituted a difficult task. For this, a thick layer of earth was laid on the inner roof boards. Although this added weight to the roof, the layer of earth acted as insulation, keeping the house cool in summer and warm in winter.

The most important element in waterproofing, however, is determining the proper slope for the roof. If the slope is too flat, water will accumulate and seep into the building. If it is too steep, tiles may slide off. On a traditional Korean house, the roof curves inward. It was after much experimentation that this concave curve was found to be highly effective in keeping out rain and creating an attractive appearance. This curved roof, which seems to cradle the sky, lifts gently at the edge of its eaves. The resulting curve of the eaves, or cheoma, is one of the most elegant aspects of Korea’s traditional architecture.

High levels of skill are required to build such a gracefully curved roof out of straight materials. Moreover, the eaves, lifted slightly toward the sky, were not only beautiful but served to moderate interior temperatures. The zenith of the sun is low in winter and high in summer. The slightly uplifted eaves drew sunlight into the house in winter while providing shade in summer, thus helping to keep the interior of the house warm and cool in each of these respective seasons.

The functional aspects of the ondol, maru and curved eaves were discovered through experimentation with the laws of nature. Such methods of coping with weather and environmental conditions reveal the wisdom of accepting nature as it is.

Maksae (end) tiles at the edge of a traditional tiled roof

A traditional roof, curving upward at the edges

ARCHITECTURE BREATHING WITH NATURE

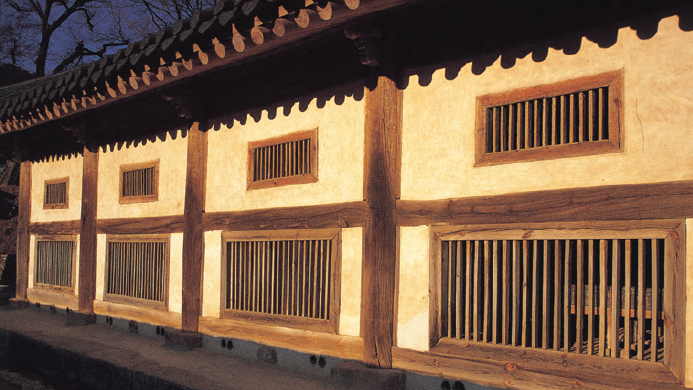

The walls of Korean houses were usually made of earth, using a variety of methods. First, a mold for the front and back was erected, then filled in. By maintaining a wall thickness of about 40 centimeters, the wind could be kept out and moderate temperatures maintained in both winter and summer. Another method involved building a framework of bamboo before applying mud to its front and back. To increase adhesion, bits of straw were sometimes mixed in with the mud; at other times, mud was kneaded with water boiled with kelp and other seaweed. Water boiled with seaweed is an excellent natural waterproofing sealant that is even used in modern construction, as it effectively keeps rain out while allowing stale air and humidity to escape through wall surfaces. When particles of earth are mixed with seaweed water, the spaces between them enable ventilation while keeping out rainwater.

Windows are built into the walls of a house to provide natural lighting, ventilation, and views of the outside. But if the windows are made of wooden slats, these three effects can only be realized when the windows are open. An open window, however, is not a reasonable option in the cold of winter.

How is it possible to maintain a comfortable temperature and provide natural ventilation and lighting all at the same time? By using changhoji, a paper whose name literally means “paper for windows and doors.” Changhoji is made from the fibers of mulberry bark. It admits and diffuses light. Changhoji could be described as a semi-transparent material. The sunlight that comes in through it is not direct, but a processed light, so to speak. Thus filtered, the light is milky and comfortable on the eye. It is neither hot nor glaring. The paper prevents the warm air from escaping outside. The use of changhoji means that the interiors of traditional Korean buildings are neither bright nor dark.

The fine spaces between the changhoji fibers block out strong winds but allow the passing of fine air particles. In a traditional Korean house with a well-designed system of windows and doors, it is said that a person will never catch a cold. Changhoji prevents cold air from the outside from coming in, but allows a certain amount of fresh air to circulate through the house. Such natural lighting and ventilation occur when the windows are closed—an effect that can only occur with paper windows. When glass windows are closed, lighting is possible, but not ventilation.

Windows arranged to provide ventilation through optimum use of natural air currents

A traditional interior with the paper-lined windows open

Close-up of a traditional wooden window pattern lined with changhoji

NATURAL INFLUENCES ON ARCHITECTURE

In all the processes involved in building a traditional Korean house—selecting the site, erecting the framework, adding the roof, and installing the doors and windows—the most important consideration was respect for nature. In traditional Korean architecture, nature was not something to be conquered or overcome; it was the model and the ideal standard for everything in the human world. The concept of “untouched nature” in Taosim does not mean going back to primitive times, but rather the creation of a safe and sound world by following the principles of and submitting to the laws of nature. Neither, however, does it mean unconditional adaptation to nature. In Neo-Confucianism, the idea of “human and nature as one” is emphasized; though architecture is a product of humanity, its technologies should respect the laws of nature, and views of the natural surroundings should be brought inside to make the house a part of nature.

Neo-Confucianism also emphasizes the spirit of restraint and modesty in humanity’s attitude toward all spaces and natural resources, which in effect means respect for and coexistence with nature. Pungsu is a highly developed system of knowledge and values which maintains that the location of a building site and the orientation of buildings should not conflict with nature. The use of crooked pieces of wood involves a construction method that makes optimal use of the natural characteristics of materials. Earthen walls and paper windows maximize the use of natural materials applied in a scientific manner, making them environmentally friendly. While all these materials are taken from nature, they are used with sensitivity and based on advanced technologies for maximum performance. In contemporary times, when the development of science and technology is so often harmful to our environment, it is worth pausing to take note of traditional Korean architecture’s respect for nature.