Korea’s opening to the West had a profound impact on its architectural landscape. Foreign architectural styles—largely from the West, but also from neighboring countries like China and especially Japan—integrated themselves into the country’s skylines. This process accelerated with Japan’s forced annexation of Korea in 1910. During their 35-year rule over their neighbor, the Japanese imperialists radically transformed Korea’s cityscapes, outwardly “modernizing” urban areas while destroying much of Korea’s irreplaceable historical and cultural heritage.

Korea’s early modern architecture comes in a wide variety of shapes and forms, reflecting the complex and dramatic nature of its late 19th and early 20th century history. To be sure, much of this architectural heritage is foreign-built, largely by either the Japanese or Western missionaries. A handful of Korean architects were also active during this period—these pioneering artisans formed the first generation of Korean modern architects.

EARLY MODERN ARCHITECTURE?

“Early modern architecture” is, admittedly, a difficult term to define. In the West, “early modernism” is simply part of the larger “modernism” movement. Beginning in the 18th century, this architectural movement reflected the great economic, social, and political upheavals of the 19th century, especially the Industrial Revolution. These dramatic transformations encouraged architects to break with traditional European architectural styles like Gothic and Victorian. Developments in engineering technology also made new forms of architecture possible.

Early modern architectural styles tended to be much more utilitarian than the more ornamental traditional architecture forms. Indeed, over time, architects would come to appreciate the beauty of raw, unadorned architectural materials, Paris’s Eiffel Tower being a perfect example. Iron and steel frame construction, the Chicago School, Art Nouveau and Art Deco, Soviet constructionism, expressionism, and Bauhaus were widely employed styles of early modern architecture in the West.

In Korea, however, early modern architecture has a very different meaning. Here it is generally defined as architecture—mostly but not exclusively Western-inspired—built between Korea’s opening to the West in the late 19th century and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, although this is sometimes extended to include modern works built in the 1960s and 1970s. This definition reflects Korea’s radically different history of modernization. As was the case in much of the colonized world, modernization in Korea was largely the result of contact with the West, either directly or through a “Westernized” Japan. Unlike the Western modern architectural movement, which reflected social, economic, political, and technological transformations, Korea’s early modern architecture reflected the import of foreign concepts and styles. Not all of these concepts and styles were necessarily “modern,” either—two of Seoul’s most beautiful pieces of early modern architecture, Myeong-dong Cathedral and Seoul Anglican Cathedral, were built in decidedly traditional Gothic and Romanesque styles, respectively. Korea’s early modern architecture also includes works of traditional architecture that have undergone “modern” transformations, such as the hanok homes of Seoul’s famous Bukchon neighborhood, built in the 1920s and 1930s using modern materials and elements.

Old Seoul Station building

Myeong-dong Cathedral

Seoul Anglican Cathedral

ARCHITECTURE OF THE DAEHAN EMPIRE

In the late 19th century, Korea found itself under threat by Western imperial powers, China, and increasingly, Japan. France and the United States conducted raids against Korea in 1866 and 1871, respectively. In 1876, Japanese gunboat diplomacy resulted in the Treaty of Ganghwa, in which Korea’s Joseon Dynasty opened up its ports to foreign trade. Korea entered into diplomatic and trade treaties with several Western powers soon after.

The opening of Korea had a profound effect on its society. Western (and Japanese) missionaries, diplomats, and traders brought new products, ideas, and institutions. In 1897, Korea’s King Gojong proclaimed the start of the Daehan Empire, and with it Korea launched a concerted effort to modernize, much as Japan had done following the Meiji Restoration.

Korea’s opening transformed the architectural landscape. To be sure, Korea had been importing—and Koreanizing—foreign architecture styles and concepts for centuries, largely from China. In the later part of the Joseon Dynasty, aristocratic Koreans and the royal court introduced exotic elements of Qing Dynasty architecture—such as brick walls and circular windows—into their homes and palaces. The Jipokjae Hall (1888) of Gyeongbokgung Palace and Seokpajeong Annex (mid-19th century), originally part of the villa of the powerful 19th century regent Heungseon Daewongun, are among the best examples of this. Korea’s opening to the West, however, allowed for altogether new foreign styles to flood in. By 1910, Western-style buildings could be found all over Seoul, including the royal palaces.

A gate in the grounds of Seokpajeong Annex

Foreign diplomats, foreign businessmen, and Western missionaries were responsible for much of Korea’s Daehan Empire-era architectural heritage, although Korea’s imperial court also pushed Western-style construction projects, often hiring Western or Japanese architects to do so. A walk around Seoul’s Jeong-dong district, the old Western legation quarter, will reveal a number of graceful buildings from this era, including Victorian Gothic-style Chungdong First Methodist Church (1897); Renaissance-style Jungmyeongjeon Hall (1900), built by a Russian architect as a royal library; the old British Legation (1892), now used as the British ambassador’s residence; and the old tower of the Russian Legation (1890), the rest of which was destroyed in the Korean War. The Daehangno district also has two splendid pieces of Western-style architecture erected at the initiative of the Korean imperial government itself: Daehan Hospital (1907), a beautiful brick edifice with a Baroque clock tower and a Norman entrance designed by a Japanese architect for the Daehan Empire’s ministry of finance; and the old National Industry Institute (1908), a German-style wooden office also designed by a Japanese architect. Deoksugung Palace itself is home to two beautiful pieces of Daehan Empire-era Western architecture: imposing neoclassical Seokjojeon Hall (1910), designed by a British architect as a throne hall for the Daehan emperor, and curious Jeonggwanheon Pavilion (1900), built in mixed Korean and Romanesque styles by a Russian architect. Catholic missionaries were also quite active in this period, erecting a number of important churches, including landmark Myeong-dong Cathedral (1898), one of Korea’s finest pieces of Gothic architecture.

While foreigners are responsible for much of the Western architecture from this period, Koreans, too, began to learn the new architectural styles. Sim Ui-seok (1854–1924), a Korean traditional architect by training, learned Western architecture through his interactions with Jeong-dong’s Western community. He participated in a number of Seoul’s major architectural projects from that time, including Western ones (Chung-dong First Methodist Church, Pai Chai Hakdang, Independence Gate, Deoksugung’s Seokjojeon Hall) and Korean ones (Wongudan Shrine, Gwanghwamun’s Bigak and Pagoda Park’s Palgakjeong Pavilion).

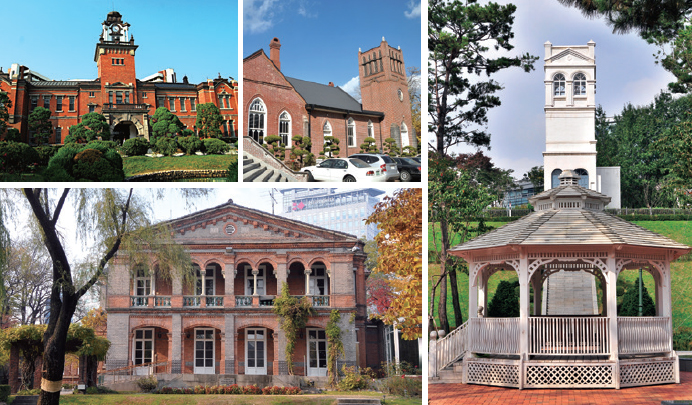

(clockwise) Daehan Hospital; Chungdong First Methodist Church; the old tower of the Russian Legation; the old British Legation

Jeonggwanheon Pavilion

Pai Chai Hakdang

ARCHITECTURE OF THE JAPANESE COLONIAL ERA

Japan’s forceful annexation of Korea in 1910 marked the start of 35 years of foreign imperial rule. The architectural legacy of colonial domination was profound. The colonial authorities undertook massive building projects in order to show off their own power and demonstrate their “modernization” efforts. Korea’s cities and towns were transformed, but at great cost to the nation’s cultural and historical heritage. This was most painfully demonstrated by the near-complete demolition of Gyeongbokgung Palace, a priceless symbol of Korea’s identity as an independent nation, to make way for a massive, neoclassical office to house the Japanese Government-General.

Western architecture had come to Japan only slightly earlier than it did to Korea. Like Korea, the Japanese had initially hired foreign architects to build their early Western buildings and teach the first generation of Japanese architects. For the last two decades of the 19th century and first two decades of the 20th, Japanese architects largely employed classical Western styles such as Renaissance and Baroque. Architecture built in Japan’s colonies at the time reflects this. The old Bank of Korea building (1912) in Seoul’s Myeong-dong district, designed by Tatsuno Kingo, one of the fathers of Japanese modern architecture, is built in French Renaissance style and resembles a French château. Monumental Seoul Station (1925), designed by a student of Tatsuno, is built in Renaissance style, but with a large Byzantine dome. Nakamura Yoshihei’s East (1923) and West (1921) Halls of Jungang High School were built in Gothic style. Beautiful Unhyeongung Yanggwan (1912), built as a home for the grandson of Korea’s 19th century regent Heungseon Daewongun, employs a Neo-Baroque style.

Old Bank of Korea building

In the 1920s, however, Japanese architects—inspired by Western architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier—began to experiment with newer architectural trends like expressionism and rationalism. Japanese architects continued their experiments in the colonies. Seoul Metropolitan Council Building (1935) and the Myeong-dong branch of Shinsegae Department Store (1930) display a modernistic rationalism. The influence of Frank Lloyd Wright can be seen in the horizontal lines and scratch tile of the old Chungcheongnam-do Provincial Hall (1932), while the unusual lines of the old Main Hall of Daegu Medical College (1933) display the influence of German expressionism.

Jungang High School

Shinsegae Department Store

Old and new Seoul City Hall buildings

Incheon Jung-dong Post Office

Japanese architects made wide use of eclecticism—the mixture of different historical and national styles to create something completely new. A typical example of this is the old Seoul City Hall (1926), which adds modern elements—for instance, stripped ornamentation—to its classical Renaissance style. A similar mixture of styles is at work in Incheon Jung-dong Post Office.

Korea’s first batch of architects trained in Western styles were active in this era, too. One of the best-known is Park Gil-ryong (1898–1943). Graduating from an engineering school in Seoul in 1919, Park cut his teeth with the Government-General’s architecture department before forming his own architectural office in 1934. Park’s masterpiece, the old Hwasin Department Store (1937), was demolished in 1987, but his flair for modernism and rationalism can be seen in two surviving works, the old Main Hall of Seoul National University (1930) and Gansong Museum of Art (1937). Park also attempted to bring Korean traditional residential architecture, the hanok, into the modern era, designing two hanok homes—Seoul’s Min Byeong-uk House (1938) and Kaksimjae (1938)—with indoor toilets and baths, glass windows, and interior hallways.

Another Korean architect active at this time was Park Dong-jin (1899–1980). Like Park Gil-ryong, he too learned the ropes with the Government-General before forming his own architectural office in 1932. Park is best known for his association with Korean businessman and statesman Kim Seong-su, through whom he came to design the beautiful Tudor Gothic main hall and central library of Korea University (1937). Other works of his, such as the Main Hall of Jungang High School (1937), Youngrak Presbyterian Church (1946), and Namdaemun Presbyterian Church (1955), were similarly built of granite in Tudor Gothic style.

POST-LIBERATION ARCHITECTURE

Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 allowed Korean architects to finally move to the fore. Unfortunately, the early post-liberation era was not an easy place in which to work. Japanese colonial rule had left Korea poor, brutalized, and worse still, divided. The Korean War, waged from 1950 to 1953, left the country devastated. In the reconstruction years that followed, with needs many and resources few, Korea’s priorities focused on the practical, not the artistic.

Nevertheless, Korea’s first generation of post-Liberation architects still found outlets for its artistic ambitions when the opportunity presented itself. More modern, rational architectural styles, particularly the International Style, also became prevalent beginning from the 1950s. Some architects, however, strove to explore Korean traditional architectural concepts, reinterpreting them in the language of modern architecture.

Kim Swoo-geun’s Freedom Center

Olympic Stadium

Korea’s two best known architects from this period were Kim Swoo-geun (1931–1986) and Kim Chung-up (1922–1988). In many ways, the men were a study in contrasts. Educated in Japan, Kim Swoo-geun showed in his earlier work the influence of masters such as Kenzo Tange and Le Corbusier. Later, however, he put much effort into re-understanding Korean traditional architecture, and employing this re-understanding in his work. In his buildings, space and structures flow together, as in Korean hanok homes. Kim’s close ties with the Korean government afforded him the opportunity to conduct a number of major projects, including the Walkerhill Hotel’s Hilltop Bar (1961), the Tower Hotel and Freedom Center (1962) on Mt. Namsan in Seoul, and Olympic Stadium (1984).

Kim Chung-up was a student of Le Corbusier, and much of his work reflects this. His masterpiece, the French Embassy in Seoul (1961), displays the rationalism of Le Corbusier, but the curved roof lines recall the sloped roofs of Korean traditional architecture. Another one of his masterpieces, the Samil Building (1970), is a textbook example of International Style and was Seoul’s tallest building for nearly a decade.

NOTABLE MODERN ARCHITECTURAL WORKS

Seokjojeon Hall, Deoksugung Palace

The imposing Seokjojeon Hall of Deoksugung Palace was built to be a symbol of the new, modern Daehan Empire. The granite hall, built in the neoclassical style, was built as a throne hall and residence for King Gojong. Construction began in 1900, but the building would not be completed until 1910, long after Gojong had abdicated. The original design was done by Welsh architect G. R. Harding, but due to the vagrancies of Korea’s early 20th century history, a number of architects, including a Russian, a Japanese, another Briton, and Korea’s own Sim Ui-seok took part in the project. The portico of Seokjojeon is held up by a colonnade of Ionic columns, while the pediment is ornamented with a relief of a plum blossom, the symbol of the royal family.

Seokjojeon Hall

Jemulpo Club

The city of Incheon was the first Korean port to be opened to foreign trade. Like China’s “treaty ports,” Incheon—or Jemulpo as it was then known—was divided into several foreign settlements, where foreigners enjoyed extraterritorial rights and ran their affairs virtually independently of the Korean authorities. To this day, Incheon’s historic waterfront area is home to many splendid examples of Chinese, Japanese, and Western architecture built during this period.

One of the better examples is the Jemulpo Club, which served as a gathering place for Incheon’s foreign community. Completed in 1901, it was designed by Afanasy Ivanovich Seredin-Sabatin, a Russian architect and engineer who authored many buildings in Korea prior to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. The simple Western-style building sits on a breezy hillside just below Freedom Park (Korea’s first Western-style park, also designed by Seredin-Sabatin), with good views over the harbor.

Jemulpo Club

Old Seoul Station

Old Seoul Station served as Seoul’s primary gateway between 1925, when the station was completed, and 2004, when a new station was built just next door to handle the recently introduced KTX high-speed train. Along with the mammoth Government-General Building (demolished in 1996), Seoul Station was one of the colonial government’s architectural showpieces and for decades one of the city’s most prominent sights.

The station building was designed by Tokyo Imperial University professor Tsukamoto Yasushi, a student of Tatsuno Kingo, the pioneering Japanese architect who designed Tokyo Station and Seoul’s own Bank of Korea headquarters. Indeed, the Renaissance-style station, with its red brick, granite horizontal accents, and massive dome, is a rather typical example of the “Tatsuno Style” widely employed by the Japanese throughout their empire. Light enters its grand central hall through distinctive Diocletian windows.

After lying unused for several years, the old station was restored and renovated and is now used as a culture and arts space.

Old Seoul Station

Old Seoul City Hall

Along with the Government-General Building and Seoul Station, Seoul City Hall was one of the colonial government’s most important showpieces of the 1920s. Completed in 1926, the imposing building is typical of colonial-era eclecticism. Designed in mostly Renaissance style, the reinforced concrete structure also incorporates more modernist elements, most notably its distinct lack of ornamentation. In contrast to the rather austere exterior, the interior is comparatively ornate. Due to the construction of a new City Hall building just behind it, the old City Hall has been renovated for use as a public library.

Cheondogyo Central Temple

Completed in 1921, the Cheondogyo Central Temple near Seoul’s Insa-dong district is the main meeting hall of Korea’s indigenous Cheondogyo religion. The grand building was designed by the architectural office of Nakamura Yoshihei, one of Japan’s leading colonial architects. Its unique Vienna Secession design, however, suggests Nakamura’s Austrian-born employee, Anton Feller, had a hand in its authorship. The roof of its cavernous central hall, held up without any pillars, is an impressive piece of civil engineering.

Cheondogyo Central Temple

Myeong-dong Cathedral

Located strategically atop a hill in downtown Seoul, massive Myeong-dong Cathedral dominated Seoul’s skyline for decades after it first went up in 1898. It was designed by French priest Father Eugene Jean Georges Coste of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, who was also responsible for two of Seoul’s other Catholic monuments, Yahkyeon Catholic Church (1892) and Yongsan Seminary (1892). The cathedral, built of red and gray brick by Chinese masons, is a masterpiece of Gothic Revival architecture. With a floor plan laid out in the shape of the Latin Cross, the church has a high vaulted nave flanked by two aisles. In true Gothic fashion, the nave is supported by an arcade, triforium, and clerestory.

The area around the cathedral is rich in early modern architecture, too, including the chapel of the convent of the Sisters of St. Paul of Chartres (1930s), the old church for Japanese worshipers (1928), Coste Hall (1939), the Seoul Archdiocese Annex (1927), and the former archbishop’s residence (1890), the oldest extant Western-style building in Korea.

Myeong-dong Cathedral

Seoul Anglican Cathedral

Considered one of Korea’s most beautiful pieces of architecture and one of the finest pieces of Romanesque architecture in East Asia, Seoul Anglican Cathedral was consecrated in 1926, although the church remained virtually half-finished until its original blueprint was rediscovered in a British library in the 1990s. Church leaders commissioned Arthur Dixon (1856–1929), a British architect and member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, to design the cathedral. The Romanesque monument was designed to blend in with nearby Deoksugung Palace and incorporates a number of traditional Korean elements, especially in its windows and roof. The beautiful gold mosaic behind the altar was done by American-born Scottish designer George Washington Jack (1855–1932).

Old Main Hall of Seoul National University

Completed in 1931, the old Main Hall of Seoul National University is one of the few remaining works of Park Gil-ryong, Korea’s first architect trained in Western architecture. The building’s modernist style can be seen in its horizontal lines, curved corners and restrained ornamentation. The building is covered in scratch tile, a relief tile invented by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright during his stay in Japan.

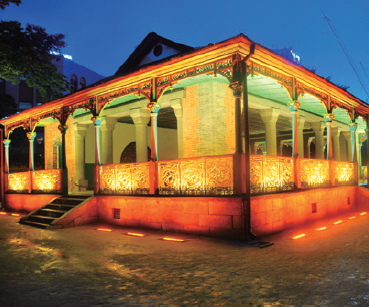

Min Ik-du House (now Min’s Club)

Also designed by Park Gil-ryong, Min Ik-du House is an attempt to bring Korean hanok architecture into the 20th century. The beautiful home near Seoul’s Insa-dong district, built in the 1930s, incorporates a number of modern elements into its design, including an indoor entrance, a bath and toilet, glass windows, and interior hallways. It would have been considered breathtakingly modern at the time. The home is now used as a fusion Korean restaurant and café.

Korea University Main Hall and Central Library

The historic Main Hall and Central Library of Korea University were completed in 1937 and designed by Park Dong-jin, one of only a handful of Korean architects active in the Japanese colonial era. The granite buildings, with their distinctive Tudor Gothic design, are said to reflect the wishes of the university’s owner and Park’s patron, influential Korean businessman Kim Seong-su. In the 1920s, Kim had gone abroad to inspect overseas universities and was reportedly most impressed by North Carolina’s Duke University—much of the campus was built in Tudor Gothic style, a style commonly employed at American university campuses at the time. Rather than reference one university, however, Park may have referenced several when designing the new campus. The Main Hall and Central Library’s Tudor arches, buttresses, and dormer windows are typical of the Tudor Gothic style.

Korea University Main Hall

Central Library

SPACE Group Building

Kim Swoo-geun is representative of the Korean architects of our time, together with Kim Chung-up. Kim Swoo-geun established his own theory about architectural space, rooted in Korean tradition—the third space, ultimate space or womb space—that he skillfully put it into practice in the SPACE Group Building.

This building, his most exemplary work, is a complete break from his earlier architectural works, which tended toward formalism, such as the Freedom Center and the Walker Hill Hilltop Bar. The construction of the Space Group Building began in 1971 and was completed in 1977 after a new wing was added. The elegant flow of various spaces, a characteristic of traditional Korean architecture, took on a modern meaning in this work.

French Embassy

Kim Chung-up’s French Embassy building is an example of adapting the later architecture of Le Corbusier to the local characteristics of Korea. In addition, Kim managed to strike a balance between the different characteristics of France and Korea.

The French Embassy building is ultimately Corbusian. Although both the architect and critics admit that the formal sensitivity was borrowed from Korea’s traditional architecture, it is actually more correct to consider it an expansion or development of Corbusian architecture. The pure architectural space of early modernism that is so evident in Kim’s Pusan National University and Sogang University Administration Hall, which were constructed around the same time, has developed into an ambiguous duality, and his creativity beyond Le Corbusier is most evident in the French Embassy building.