6.1 Introduction

This chapter explores the potential of the concept of sociotechnical imaginaries for digital touch communication research and design. We discuss how this concept can be employed to explore digital touch, as both a design resource, and as a methodological resource. We argue that as new digital touch technologies enter the communicational landscape the setting for interpersonal sociability is/will be reworked. We explore and make legible emerging sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch, asking how might touch practices be changed through the uses of technology, and how might this shape communication. The core themes of the body, time, and place are discussed in relation to case study participants’ sociotechnical imaginations of digital touch. Turning our attention to the sociotechnical imaginary as a methodological resource, we describe our use of a range of creative, making and bodily touch-based methods across the InTouch case studies to access participants’ sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch and to both explore and re-orientate to the past, present and futures of digital touch communication. First, we outline what we mean by the term sociotechnical imaginaries and why it matters for digital touch.

An imaginary describes people’s visions, symbols and associated feelings about something. The social imaginary resides in society rather than an individual person’s mind and refers to the “common understanding that makes possible common practices and a widely-shared sense of legitimacy” (Taylor 2004: 23). These imaginaries help to produce shared systems of meaning and belonging that guide how people collectively see and organize the world, in its histories as well as its futures (Jasanoff and Kim 2015). The sociotechnical imaginary refers to “collectively held and performed visions of desirable futures…animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology” (Jasanoff 2015: 25).

Appadurai (1990) links the social imaginary with the global cultural flow of ‘Technoscapes’, that is, the ways in which technology promotes cultural interactions. The development and usage of all technologies is embedded within and animated by social imaginaries (Herman et al. 2015). While Flichy (2007) argues that there are a range of imagined technological possibilities at the root of a sociotechnical context that warrant investigation, ‘not as the initial matrix of a new technology but rather as one of the resources mobilized by the actors to construct a frame of reference’. As this makes clear, social imaginaries serve “as a key ingredient in making social order” (Jasanoff and Kim 2015: 122) and thus have real material outcomes, rather than being ephemeral visions.

The concept of the sociotechnical imaginary has significant theoretical and methodological power for understanding digital touch communication. We use examples from our case studies to illustrate our use of sociotechnical imagination first to explore digital touch to make legible emergent sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch; and second, to generate new methodological routes towards digital touch futures. InTouch is interested in emerging sociotechnical imaginaries of touch as it is digitally mediated. We ask how the imaginary is articulated across different levels, including that of the individual, which, while less uniform, is always connected to dominant social imaginaries – even if through opposition or resistance to them.

6.2 The Sociotechnical Imaginary as a Design Resource

The sociotechnical imaginary is a key concept, albeit often implicitly, for researchers, engineers, computer scientists and designers working with digital touch. It is used to explore how people make sense of their visions and practices with communication systems, for example, Mansell’s Imagining the Internet (2012). The imaginations of media and popular culture, particularly the alternate realities of science fiction, are a rich source of inspiration for future digital innovation that is drawn on by engineers, computer scientists, and designers (Finn and Cramer 2014; Shedroff and Noessel 2012). The imagination is also drawn on as a form of critique, “By acting on people’s imaginations rather than the material world, critical design aims to challenge how people think about everyday life” (Dunne and Raby 2013: 45). Speculative design has engaged with the imagination (albeit to different extents) to ask provocative questions and disrupt thinking rather than to create design solutions (ibid). Beyond these, sometimes fantastical, futures, however, the imagination pervades the ‘everyday’ processes of researching and designing digital touch. It weaves through ideation and development (e.g. imagining people’s expectations) and the lived social contexts that are evoked through the processes of research and design.

6.3 The Sociotechnical Imaginary as Methodological Resource

We use the sociotechnical imaginary in InTouch as a methodological resource to examine past, present, and future experiences, desires, and fears of touch and remote communication that may shape the evolving digital landscape of touch. It is a useful framing device with which to explore emerging digital touch communication as the majority of digital touch technologies are at an early stage of development, unstable and un-domesticated, in labs rather than ‘in the wild’. As a result, observing their everyday use is impracticable or impossible. Further, in addition to the norms of digital touch (see Chap. 4), the potentials for using digital touch to communicate, the forms that this might take, and the contexts of use are in an unsettled state of flux. Highlighting the value of using the socio-technical imaginary of digital touch, to bring the social aspects of digital touch communication to the table of technical development. In our research, we use the concept of the sociotechnical imaginary to frame our exploration of participants’ emergent desires, concerns and preoccupations within speculative futures, and to trace the intimate connects of these futures to the present and the past. Exploring case study participants’ narratives of continuity and change through this lens enables us to generate a discursive space which “oscillates between imagination and reality” (Kim 2018: 176–7). This has enabled us to “engage directly with the ways in which people’s hopes and desires for the future – their sense of self and their passion for how things ought to be – get bound up with the hard stuff of past achievements” (Jasanoff 2015: 32).

The unprecedented is necessarily unrecognizable. When we encounter something unprecedented, we automatically interpret it through the lenses of familiar categories, thereby rendering invisible precisely that which is unprecedented. …the unprecedented reliably confounds understanding; existing lenses illuminate the familiar, thus obscuring the original by turning the unprecedented into an extension of the past. (Zuboff 2019: 12)

While the boundaries of digital touch are being pushed to new frontiers, our case studies show that the tactile affordances of current technologies combined with the social norms of touch persistently shape the future visions of digital touch. At times these histories actively constrain and limit the visions of designers and potential users. Whilst acknowledging these difficulties, we cautiously wrap the sociotechnical imaginary within our multimodal and multisensorial approach to ‘illuminate the role of imagination in the fabrication of social lives’ (Appadurai 1990) with respect to digital touch communication.

6.4 Making Legible Emergent Sociotechnical Imaginaries of Digital Touch

As new digital touch technologies enter the communicational landscape, the setting for interpersonal sociability will be reworked. We set out to explore and make legible emerging sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch; how touch practices might be changed through the use of technology, and how this might shape communication. Alongside the literature, we draw on illustrative examples from the InTouch case studies, notably Imagining Remote Personal Communication, Designing Digital Touch, and Tactile Emoticon.

Participants in the Imagining Remote Personal Communication case study engaged in prototyping to elicit their digital touch imaginaries

6.4.1 Body

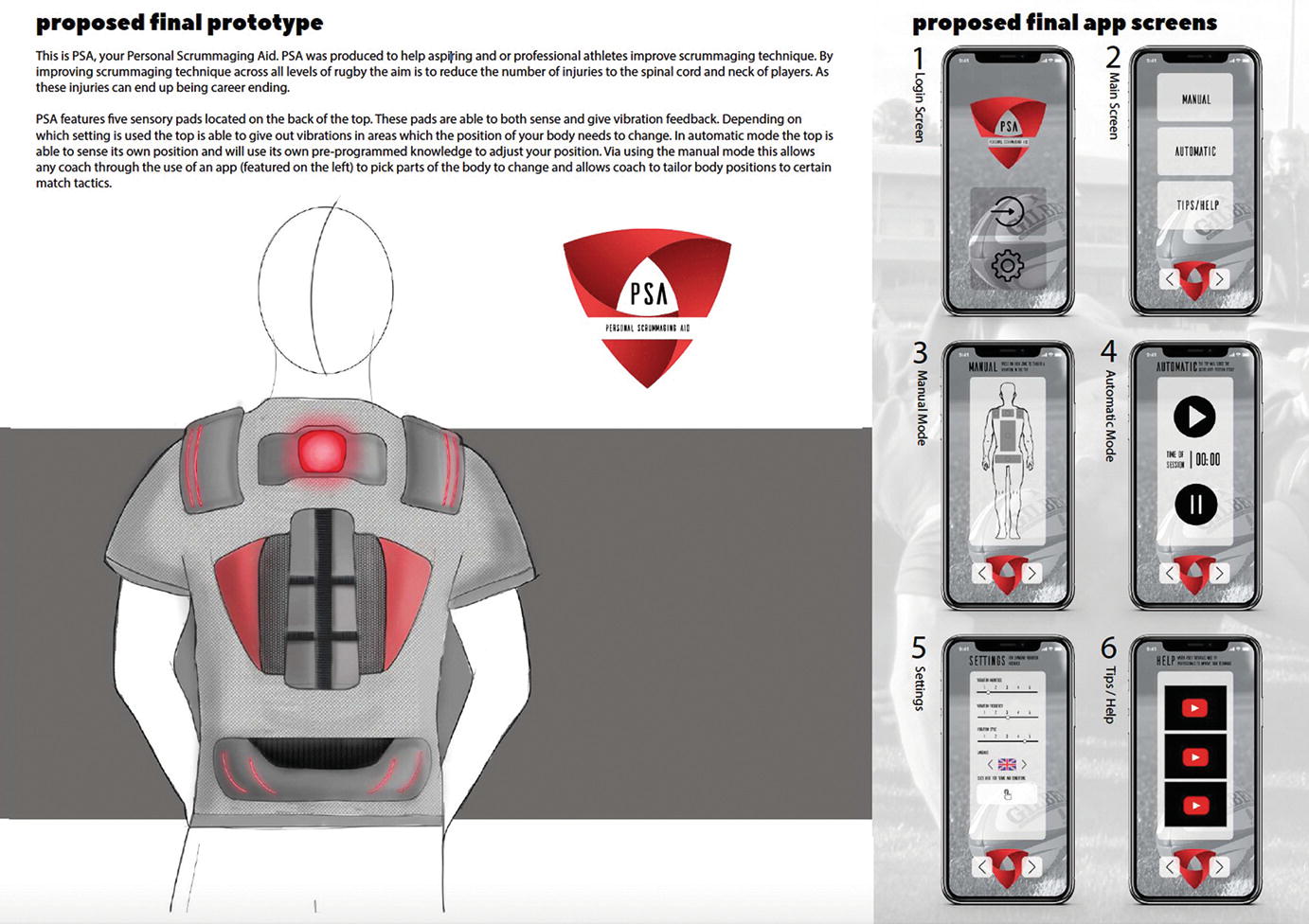

Example of the use of vibration as a form of tactile correction in the Designing Digital Touch case study|Personal Scrummaging Aid by Ben Cook: https://issuu.com/bencook11/docs/hd_portfolio (© Ben Cook)

Sometimes touch is really painful. What I really wanna communicate is ‘don’t touch me!’ and that is very hard, particularly in a busy city…I’m imagining that all the bad emotions can get filtered off! And the good emotions can get through…so that they can be sensed like where ever your threshold is.

Participants interacting with the Tactile Emoticon device

6.4.2 Time

Explicitly adding touch to the imagined communicational landscape explored across our case studies made legible debates around societal fears of ‘new technologies’ – digital privacy and safety, as well as questions of governance of touch, regulation and power. The temporality of touch was central to this imagining. Touch temporalities, the reproduction, traces and records of touch were a key aspect. Participants in the Designing Digital Touch and the Imagining Remote Personal Touch case studies worked with technological, social, and emotional temporal features of touch to structure different touch temporalities and communication experiences through their prototypes. These touch temporalities were shaped through their experiences of different media in terms of communicational “time-effort”, “immediacy”, “spontaneity” and “speed” and managing “response time”, and “obligations and expectations”. Temporal features included the duration of a touch-experience, social timing of touch (e.g. a special, every-day or routine time), the a-synchronicity or synchronicity of a sent touch. Prototyping enabled them to explore the practicalities of receiving and responding to a digital touch (e.g. the ability to turn touch on or off), the social time and place for touch (“not in the street!”) and the communicational consequence of not being available to receive a touch were explored through prototyping (e.g. the potential, and consequences, for scheduling-touch, the inclusion or exclusion of record and replay features – pause, repeat), the storage of touch and timed-filters to manipulate touch (e.g. “amplify”, “reduce”, or “remove” touch). Many participants focused on the use of touch for time efficiency, others wanted to ameliorate the social impacts of (too) fast communication temporality or to orchestrate touch in relation to shared routine time, others rejected this temporal structuring as ‘too staged’, ‘practiced’ and feeling ‘in-authentic’ and set out to create an ‘un-orchestrated immediacy’, with dedicated time for touch communication they designed an element of excitement and anticipation (imagination) of touch into their prototypes. This suggests that, at least for some participants, digital touch has potential to recover time, a form of resistance to the disciplining of the communicative body desired by contemporary industry and capital (Parisi and Farman 2019). In this way, digital touch was imagined as having a potential for a more intimate and sensorial, felt way of being together extending the ‘ambient-presence’ afforded by long duration skype, resonating with evolving temporal practices of digitally connected or mediated presence (Christensen 2009; Madianou 2016). Through, for example, the conceptualization of connecting through the long-settled touch of domestic intimacy (e.g. the Haptic Chair, Bed-Touch) – drawing on the potentials of touch to secure permanence and the management of the blurry boundaries between absence and presence (Licoppe 2004). These participants conceptualized digital touch, at least for remote personal communication, as having different temporal durations and qualities than digital communication involving visual and audio modes. Digital touch had a longer duration in contrast to the bite size voice message or mobile call, the brevity of a written text or tweet, or the visual flash of snapchat or Instagram. This, together with emplaced and embodied touch, set digital touch apart from contemporary ‘anytime, anywhere, anybody’ modes of communication.

6.4.3 Place

The Place of digital touch was made legible through the participants’ imagination and discussion as key to how technology and communication mutually constitute, organize and structure one another and the practices of digital touch. Participants approached digital touch as more intense, and riskier than other forms of communication. The Designing Digital Touch case study explored digital touch in the context of health and well-being, leisure/sport, and generated design scenarios that explored the remote administration of digital touch in a range of public settings. In contrast, the home was the primary imagined space for remote personal touch in the Imagining Remote Personal Communication and the Tactile Emoticon case studies. Participants reflected on how mobile connectivity reconfigures their spaces of communication to stretch and shrink communicational time and language (e.g. across public and private transport). They associated the ‘anywhere, anytime’ dimension of mobility to authentic ‘in-the-moment-communication’, but the ways that they imagined the time and space of digital touch disrupted this contemporary mantra. As one participant said, “Where would this happen? Not on the street? It’s so personal. I wouldn’t feel comfortable. You are walking in the street. I want to sit on the sofa at home and feel this warmth, cos it’s like personal. Out of the home –NO!” In these two case studies, the majority of participants did not include mobility as a key concept for their design of digital touch for remote personal communication, locating digital touch in a domestic and private place: usually the home: a tactile equivalent of the sonic-quiet sought for a spoken conversation appears to be a place where the body is at rest, static with a calm heartbeat, ready to be ‘activated’. Three analytical rationales appeared to underpin this domestication of digital touch: touch as intimate and taboo; the ‘slower’ temporal quality of touch; and the sense that it requires a “prepared place” including a preparing and imagination of the self and the other for communication (Cantó-Milà and Núñez-Mosteo 2016: 2409). This emerging social norm may lessen over time enabling digital touch to come out of the home, changing practices and capacities and giving rise to a need for different kinds of touch awareness and sensitivity in the management of communication.

The sociotechnical imaginaries that Virtual reality (VR) emplace touch in a common virtual space that collapses the distance between the people (users) in physical places, to bring them into connection via a shared tactile experience. Touch takes place in the virtual space and it is digitally transmitted and physically felt in these different locations. It is the type of virtual environment and the affordances – possibilities and constraints of the VR peripherals and the narratives supported by that environment, rather than those of the physical place of the users, that determines the types and norms of touch that are brought into the virtual interaction. Place is often a point of contrast in VR, for example, dystopian science fiction VR environments often juxtapose a polished virtual space with a destructed real-world space. This contrast is designed to demonstrate a sense that the physical does not matter with the physical body positioned as a mere container, emphasised by the body often being imagined as isolated in such VR environments. In contrast, the virtual space is positioned as the one that matters, because it is a shared space which hosts and facilitates co-presence and touch. Furthermore, in these imaginaries the virtual becomes a refuge from the physical or an ‘alterity’ (a different reality) where different rules, constraints, possibilities and opportunities apply. Users in a virtual world can, depending on the social and technological affordances available to them, reshape their ‘bodies’, re-fashion who they touch, how, when and in which spaces they touch. These imaginaries demonstrate how the emplacement of touch in a virtual space can accomplish a realistic tactile connection with the physical body, generate questions about the body, physical space, the forms and norms of touch, the boundaries between the physical and the digital as well as the resources which the virtual can bring to touch experience.

Three key cross-cutting themes emerged through the participants’ articulations of the sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch communication outlined above in the form of speculations on touch with regard to the politics of touch, the representation of touch and the ethics of touch. The politics of touch emerged as a theme through participants’ (and the researchers’) constant debates on touch agency and power: who is being connected via touch, who touches and who is touched, who is untouched, the control of touch, and the types of touch contexts brought into the realm of digital touch (whose touch is important enough to be digitally ‘fixed’ or enhanced)? The representation of touch and questions of whether (and how) digital touch is mimicking or reconfiguring touch weave through the sociotechnical imaginations of touch made evident by the case studies. They include questions of continuity and change, that is, what forms of touch persist or are lost in the digital remediation of touch, the materiality and affordances of digital touch, its reproduction, traces, recording storage and sharing. The politics and representation of digital touch intersect with the ethics of digital touch, including touch authenticity, privacy and care; themes brought into focus in Chap. 7.

6.5 Generating New Methodological Routes to Imagining Digital Touch Futures

In order to explore the complexity of digital touch, we use a range of methods across the InTouch case studies to engage participants in creative processes, making and bodily touch-activities with themselves, others, materials and objects, that deliberately go beyond the linguistic and the individual. These methods enable us to access participants’ sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch communication and to both explore and re-orientate to its past, present and futures. This has included asking participants to engage in rapid-prototyping of a digital touch communication device, system or environment (discussed above); producing a design-concept video to demonstrate a digital touch user experience; developing or engaging with future scenarios for digital touch; using excerpts from film and fiction as speculative prompts; and interacting with a variety of digital research probes. These methods provide opportunities for participants to reflect on the rich complexities of touch and are particularly adept at accessing participants’ sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch communication. Generating new research spaces for digital touch can help to open up new routes for participants to reimagine touch. We illustrate this approach with reference to the Tactile Emoticon, Art of Remote Contact and Designing Digital Touch case studies. Though these routes necessarily always tie back to the present and the past of touch, we seek to stretch these threads to explore the new social boundaries of digital touch communication.

Design-workshops and prototype ideation and iteration informed the final Tactile Emoticon Device

The Art of Remote Contact case study exhibition – Remote Contact, provided an exploratory tactile space for new touch experiences

The visitors to the exhibition engaged in touch interactions with one another – often with strangers, and with artefacts as objects. The artefacts provoked playful and exploratory ways of touching, including attempts to disrupt the expected ways of touching. This sparked conversation about touch and touching, surfaced questions about touch, pleasant and unpleasant emotions and memories of touching, imaginations of being alone and well-being. It also provoked in-the-moment reactions to touch (e.g. discomfort in holding a stranger’s hand). The ‘I wanna hold your hand’ artefact, in which visitors held hands, for example, prompted talk of the sensitivity of holding hands, the functions and contexts of doing that, the gendered character of touching, the politicization of touching (or not touching), and individuals’ experiences of hand-holding with parents, children, and loved ones, often in the context of family and professional contexts.

There should be some relationship between colours and movement. Colour communicates something, so the screen should change in response to me. I don’t know my heart rate, or temperature or something so that you can create a new image by externalising your internal feelings. [The visitor is associating the ‘touch data’ with emotion.] That would make you become more aware of yourself, but also how the other person [that you are interacting with via the Motion Print] is making you feel. If it could do those things then the communication between one another would be pleasing and interesting and it would help you think in new ways about how you could transfer what you do intuitively when you touch somebody. How do you make this stuff that is so easy, and familiar and intuitive available for thought? By externalising it, de-familiarising it, and in order to do that, you have to be able to see the connection between what you are doing and the technology.

They are mechanical, I think for me touch is much softer than what these marks, I wouldn’t look at them and associate them with holding someone’s hands, they would need to be [she fluidly moves and squeezes hands] more organic and softer… do you know what would be great? Is to have a knitting machine instead of a pen, and you could wear it, and someone’s touch has made the jumper.

These examples illustrate how the concept of the sociotechnical imaginary can generate new routes to explore digital touch futures, including the materiality of digital touch, social norms and practices, tactile traces, records and representation.

The development of the Designing Digital Touch Toolkit. Developed in collaboration with Dr. Val Mitchell and Dr. Garrath T. Wilson, School of Design and Creative Arts, Loughborough University

The Toolkit is designed to support engagement with the complexities of working with touch. For example, it helps participants to reflect on different types of touch, what touch might mean and feel like in different contexts, as well as bodily sensations and social and cultural boundaries of touch. The Toolkit has three types of cards: ‘Filters’ – questions to help participants reflect on their own and others’ experiences; ‘Wild cards’ – deliberately abstract prompts for thought or action; and ‘Activities’ – more structured exercises which require some time. In this way, the Toolkit guides the user by providing new and divergent routes into their imagining of digital touch futures. For instance, a student design project on environmental awareness worked to engage parents and children in gardening and growing plants together towards developing new relationships between people and plants. The length of time a seed takes to germinate was, the student noted, a significant ‘pain point’, as there is nothing to see and the children become disengaged. Working with the toolkit, they explored ways in which touch could be used to communicate the ‘in-pot’ activity of the seed to the child through changing temperature, and tactile sensations.

6.6 Conclusion

This chapter has outlined the concept of the sociotechnical imaginary and illustrated its theoretical and methodological potential for understanding digital touch communication as a design resource, a methodological resource, and a topic of study.

The sociotechnical imagination featured as a design resource for the students and participants exploring the futures of digital touch, notably in the Designing Digital Touch, Imagining Personal Touch Communication, and the Tactile Emoticon case studies. In addition to understanding the sociotechnical imaginaries that circulate among the users and contexts that we are researching and designing for, this chapter makes the case for exploring our own sociotechnical imaginaries, towards an explicit awareness of how they that underpin and drive our research and design of digital touch. Such an awareness can enable us to better articulate the social parameters that underpin our work, in order to understand how our imaginaries ‘tacitly’ constrain and afford research and design. It can provide a springboard from which to move beyond, extend, or disrupt them.

As a methodological resource, the concept of the sociotechnical imaginary worked to generate new routes to imagining digital touch futures through the making of rapid prototypes of digital touch devices, particularly in the development of the Remote Contact exhibition research space, the digital touch experiences we were able to explore via the Tactile Emoticon device, and the Designing Digital Touch Toolkit.

As a topic of study, the sociotechnical imaginary enabled us to flesh out the sociality of digital touch communication by making legible emergent imaginaries of digital touch communication, providing critical understanding and insight on digital touch communication futures, and excavating and interrogating the features of sociotechnical imaginaries that ‘tacitly’ constrain and afford research and design of digital touch. We have discussed how the participants’ sociotechnical imaginaries of digital touch communication related to the body, temporality and spatiality and drawn out three key themes that emerged through these articulations and deployments of the sociotechnical imaginary, in the form of speculations on touch with regard to the political economy of touch, the representation of touch and the ethics of touch – a theme taken up in the next chapter.

At a moment where the gap between the science fiction of digital touch communication and reality appears to be quickly narrowing, perhaps the sociotechnical imagination enables us to glimpse some aspects of our potential digital futures, and to engage with thinking what we want from the sociality of digital touch communication. Exploring sociotechnical imaginaries is therefore a vital resource towards a future agenda for the relatively uncharted territory of digital touch.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.