The rise of special education in Norway dates back to the early 1880s. Originally, special education was strongly influenced by the Age of Enlightenment and religious and philanthropic commitment to disadvantaged children. This chapter describes the development of special education by examining five critical eras, namely, The Era of Philanthropy, the Era of Segregation – Protection for Society, The Era of Segregation-Best Interest of the Child, The Age of Integration – Social Critique and Normalization, and The Age of Inclusion. Also, included are sections on the origins of public education, teacher preparation aspects, approaches to special education, working with families, and important legislative acts that support the right to education for students with disabilities. The chapter also explores the tension that exists today between regular and special education due to Norwegian legislation that emphasizes that students that do not benefit from regular education have a right to special education. The chapter concludes with a discussion about the future challenge to special education, namely, the efficacy of special education.

THE RISE OF SPECIAL EDUCATION IN NORWAY

The history of Special Needs Education in Norway dates back to the early 1800s, when it was strongly influenced by the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment and an increasingly religious, philanthropic commitment to disadvantaged children. The origins of the first special needs educational institutions are to be found in a coming together of the rational and the humane, a meeting between the Enlightenment’s fascination with and exploration of man’s possibilities and limitations on the one hand and a Christian charity on the other. For Norway and the Western World in general, new perspectives in knowledge, institutional models and methods for deaf, blind, intellectually impaired and socially maladjusted children and young people emerged in the Western World in the years between 1770 and 1830.

Two different approaches can be identified in the early history of institutions in Norway. The first approach originated in Paris and derived from a scientific, medical interest in children and young people with physical or intellectual disabilities. It came to Norway with the establishment of our first institution for special education, the institute for the deaf in Trondheim which opened in 1825, and was later followed by an institute for the blind (1861) and an institute for the educationally subnormal or those whom we now refer to as having intellectual disabilities (1874). In 1881, the above three groups were brought within the remit of a common law – the Act on ‘Teaching of Abnormal Children’, or Abnormal School Act (Government of Norway, 1881), as it was called. This was a sign that special needs education was now a public concern, an undertaking that required ‘Society’s Contribution’, although it also continued to rely on private support.

The other approach is associated with children and young people who are socially maladjusted either because of their background or behaviour. They were not classified as ‘abnormal’, but described by words such as ‘neglected’ or ‘morally corrupted children’. This approach was not intended to develop specific teaching methods and technology to deal with the students’ problems, but to establish a completely new environment for upbringing and care as a substitute for the child’s family. The first establishment of this type to arrive in Norway was established in Oslo in 1841 under the name Toftes Gave, originally referred to as a ‘rescuing institution’ and after a few decades as an ‘educational care establishment’. In 1896, the Norwegian educational care establishments were brought within the scope of the ‘Law on the Treatment of Neglected Children’, known as the Child Welfare Council Act (Government of Norway, 1896) and were now called ‘reform schools’, and the model institution Bastøy was opened at the same time.

On the basis of this the first era in the history of special needs education during the 1800s can be described as the era of philanthropy. The next era begins with two separate laws at the end of the 1800s, the Abnormal Schools Act and Child Welfare Council Act, indicating that the state now steps in and takes responsibility for the upbringing, education and care of disabled children. They become ‘children of the state’ with the development of a system of institutions based on strict segregation through the first half of the 1900s. The third era was ushered in by the Special Schools Act of 1951 (Government of Norway, 1951). This act gave Norway a general special schools system which embraced institutions that previously fell under the Abnormal Schools Act (1881) and Child Welfare Council Act (1896), bringing the blind, deaf and dumb, intellectually impaired and children with maladjusted social behaviour, behavioural difficulties, as they were called, under one and the same law. The two historical approaches were thus combined under one and the same law – and Norway ended up with one system. This system would still be based on an ideology of segregation, but at the same time people began to have doubts about the effect of the institutions and the treatment of children. The change came in 1975 with the ‘integration reform’. The Special Schools Act was now integrated with the Primary and Lower Secondary Schools Act (Government of Norway, 1975). Special needs teaching in principle are incorporated within ‘normal schools’, that is to say primary and lower secondary schools, the integration of the acts being based on an ideology of normality. The era of integration lasted until 1997, when it gave way to a new era, as we can describe the Reform Document which introduced the fifth and current epoch, the Norwegian Curriculum Plan of 1997 (Government of Norway, 1997). The plan is based on ‘adapted learning’ rooted in the principle of inclusive education, which had some years beforehand had been adopted as the guiding principle at the UNESCO World Conference on Special Needs Education in Salamanca (UNESCO, 1994).

Having outlined the five eras, we shall now go on to demonstrate more specifically how the changing ideologies and reforms shaped the development of special needs education in Norway.

The Era of Philanthropy (1825–1880)

The philanthropists, who took the initiative to establish institutions in the 1800s, wanted to perform their good works without any help from the Government or public funds. They were only answerable to God. The concept of philanthropy was far from new. It derived from the Greek expression fil antropos – ‘friend of humanity’, and was best understood in everyday parlance as an expression for benevolence, kindness or generosity – a Christian charity. The spirit of philanthropy was able to flourish in Norway in the 1800s on the basis of the principle of liberalism, which required the state and the government to exercise restraint in favour of private initiatives. This created the political basis for a flourishing, Christian, private benevolence, primarily directed towards children and young people, who in their innocence were considered to be ‘the deserving poor’ that prevailed over other groups who were themselves considered to be ‘to blame’ for their situation.

The guiding principle for the philanthropists was charity – love for a stranger. ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’. In the Christian concept of love, your neighbour is someone who needs help, but from whom you cannot expect anything in return (Nygren, 1965, 1966). Love for a ‘neighbour’ is not like love for a relative or friend; it is directed at strangers – even your enemies. This distinguishes Christian charity from other forms of love, such as erotic love, parental love or affection between friends. The philanthropists wanted to get back to Augustine’s caritas synthesis (compassionate love) – which arose from the connection between eros and agape, eros stood for man’s longing and striving upwards to God, a yearning to be loved and gain salvation, whereas agape expressed a universal love for man in God’s image which seeks to help and save mankind. In terms of the caritas synthesis, charity is not a love that sacrifices all, because it considers love to be a need in man. Considered in this way charity is not just a means of giving, but also a way of receiving.

The blind, deaf, disturbed and morally maladjusted children were all given prominence in the name of charity. But they also attracted a rational, scientific interest, particularly based on medical knowledge. The mythical delusions on witchcraft and other devious causes of disability common in the Middle Ages had been cast aside, it was understood and accepted that the disabled were not to blame for their own fate. This also applied to socially and morally maladjusted children, it was accepted that they could not be held responsible for the situation in which they found themselves, which had been caused either by poverty or parental neglect. All the above groups represented a deviation from what was considered normal. Questions were asked about the limits that could be set. What could be achieved from teaching, development and improvement within the different groups? How the message of charity would be reflected in the establishments’ teaching work and particularly in the pastors’ meeting with the child.

International pioneers included the theologian and lawyer, Charles-Michel de l’Épée, in the education of the deaf, the linguist, Valentin Haüy, in the teaching of the blind and the psychiatrist, Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, and his student, the physician Édouard Onesimus Séguin, in the teaching of the educationally subnormal (Thuen, 2008, p. 88). These individuals established the first institutions for children with medical disabilities on a universal basis – or institutes as they preferred to call them, to give their work a more professional image. l’Épée opened his institute for the deaf in 1770, in 1784 it was the turn of Haüy’s institute for the blind, and in 1837 Séguin commenced education for pupils who had been diagnosed as ‘idiots’. All three pioneers were located in Paris, where they also gained recognition and honours in the French Academy of Sciences. Common to all of them, apart from the medical-diagnostic approach, was a desire to stimulate the development of children’s moral, intellectual and mental capacity through education. Particular importance was attached to identifying the wishes of the child. Diagnostics, teaching technology and education together formed a new blueprint for the institutions, adapted to suit the different groups. In Norway the first institute for the deaf and dumb was established in 1825 (Trondheim), the first institute for the blind in 1861 (Oslo) and the first institute for the educationally subnormal in 1874 (Oslo), all significantly influenced by the above Paris institutes.

The moral educational care institutions for their part sought inspiration from the writings of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and the establishments he and his successor, Philipp Emanuel von Fellenberg, set up in Switzerland. Then Johann Hinrich Wichern’s established Das rauhe Haus, a model for many outside Hamburg. A number of observers from the Norwegian establishments visited Wichern’s establishment and returned home bursting with enthusiasm. The educational care establishments took over full responsibility for the care and education of children from their parents. Their institutional educational theory either aimed at family model along the lines of Pestalozzi’s or Wichern’s establishments, or they could organize their activities on the model of a military ‘barracks’, which some preferred. The educational care establishment was a total institution along the lines of a prison, but based on the principle of educational care and not punishment of children, whereby children were not imprisoned after a judgement passing a sentence for a specific number of years. The educational care establishment could on the contrary detain the child as long as it was considered necessary; it was up to the establishment’s directors to assess when the child was sufficiently ‘improved’ to be discharged. In individual cases the Norwegian establishment could have custody of children from the age of six years until they were 19–20 years old. In other words, this approach involved the development of an all-embracing institutional system of education.

Elsewhere in Europe and in North America the educational care establishments were prolific from the 1820s onwards and were referred to as ‘Houses of Refuge’ (North America), ‘Reformatory Schools’ (England), ‘Rettungsanstalten’ (Germany) and ‘La Colonie Agricole’ or ‘Le Péntencier Agricole’ (France). In Norway, the first educational care establishment was founded in Oslo in 1841. One particularly distinctive feature of the Norwegian establishments was their location on islands. This was partly because the island establishments were more difficult to escape from than establishments on the mainland and partly because educational work on an island could be accomplished away from and undisturbed by their surroundings.

The Era of Segregation: Protection of Society (1880–1950)

International research literature tends to make a distinction between private, philanthropic child care and public care by using the terms ‘child rescue’ and ‘child saving’ (Thuen, 2002). The difference in concepts is based on the idea that ‘rescue’ (child rescue) derives from a private commitment rooted in civil society. It is the charity of the individual, the act of rescuing a fellow human in need that is the driving force in this form of child care. The shift to ‘child saving’ takes place when the Government intervenes in the care by means of laws, making it part of a public commitment. This coincided with the transition from a constitutional to a social basis for the government’s action, which is evident in significant parts of the Western world between 1870 and 1920. Care was now increasingly to be motivated as a ‘safeguard’ in a spirit of solidarity with society. There was a desire to protect the individuals who were least capable of protecting themselves and a desire to protect society from the individuals who might harm it.

The emergence of the welfare state in the early 1900s gave rise to questions: What responsibility should the Government take for the education of the disabled? Should legislation also provide for their compulsory education? If so what would be the best way to provide for education outside ‘normal school’? The answer was given by the act concerning ‘Treatment of Abnormal Children’, or the Abnormal Schools Act of 1881, as it was known. With this law, Norway became the first country in Europe to introduce a common law for disabled children. The term ‘abnormal’ had been used for some years as a generic term for the blind, deaf and dumb and the educationally subnormal. Similar questions were asked with reference to the concept of child protection: What responsibility should the Government have for the care, upbringing and education of the children who displayed deviant social behaviour at school and in the home environment or whose parents were unable to take care of them? The answer was provided by the act on ‘Treatment of neglected Children’, or the Child Welfare Council Act of 1896 as it was known. The Abnormal School Act and the Child Welfare Council Act heralded a decline in importance of philanthropy and special needs education and child protection now became a public concern. Special needs education was still reserved for children with medically diagnosed disabilities, whereas children with social behavioural difficulties were allocated to child protection.

The two acts must be seen in the context of the introduction of the Norwegian Elementary School Acts in 1889. These laws, one for the towns and one for the country, were intended to modernize and bring democracy to primary and lower secondary school education. The fundamental aim was to create a standard common school for all children between the ages of 7 and 14 years, and thus do away with the old school system divided by class. But the concept of a common school did not apply to everyone. Disabled children were left out. Both the Abnormal Schools Act and the Child Welfare Council Act sought to separate disabled and difficult children from the elementary schools, based on a desire to create a ‘good’ elementary school for ‘normal pupils’, avoiding the disruptive effect that disabled and maladjusted children might have on the teaching. There was no issue with the right of the disabled to education in general and their obligation to participate, but with their rights within the context of the elementary school, or normal school. It was decided that children who had ‘intellectual or physical Deficiencies’, who had contagious diseases, or who influenced other school children with their bad behaviour, could be excluded. At the same time, the Elementary School Acts gave the local authorities the right to establish extra tuition or special tuition, but without obligation. Rather paradoxically, the idea of making schools more democratic, enshrined in the acts of 1889, led to a separation of pupils who were considered not to belong there. If the idea of a school for all, even for children from the upper social strata of the community, was to become a reality, the children who it was feared would tarnish the quality of teaching, had to be left out.

The Abnormal Schools Act and the separation paragraphs in the Elementary Schools Act actually laid the foundations for an extensive, differentiated special school system in Norway. The reason was twofold. The Abnormal Schools Act was conceived out of a professional interest in the disabled who were ‘educationally competent’. Thus, the law was itself a segregating law that separated the disabled into two groups, the educationally competent and the non-educationally competent. The law represented a continuation of the concepts of the Enlightenment and the belief that teaching and education of disabled children was of value and beneficial. The aim was to impart to children ‘as far as possible’ a knowledge that corresponded to the common schools’ aim of a Christian and civic education, but the abnormal schools were also supposed to prepare the students for working life. The law was effectively a law of enforcement based on the practice that all abnormal children had to be registered and assessed for a place in a school which was almost always a long way from home, thus representing a drastic infringement of parental rights. The decision to separate made in the Elementary School Acts was not justified out of any consideration for the disabled but as a way of protecting the elementary schools as a normal school. In other words, it was an institutionalized protection of normality. Although the basic motivation was different the Abnormal Schools Act and the Elementary Schools Act became coordinating aspects of a system of segregation that gradually produced a system of institutions ranging from extra tuition and special tuition to boarding schools and work and foster homes.

How did this system fit into the era? In Norway the educational concepts were taken from Europe. The German periodical Der Heilpädagog, was particularly well known. It discussed educational and teaching issues associated with a broad spectrum of children with disabilities. There may have been several reasons why Norway nevertheless became the only European country to introduce a common law in the 1800s. In the preparatory and processing stages of the act practical considerations, such as the additional work involved in the development of three laws and the fear of favouring one group over the others, were raised (Aas, 1954; Simonsen, 1998). Froestad (1995) thinks that the fundamental explanation is more likely to lie in the understanding of handicap as a social construct. The various ‘deviant groups’ were lumped into the common category ‘abnormal’ as a separate group in relation to the ‘normal’. This enabled the normal classes to be freed from deviant children who were to be transferred to ‘auxiliary schools’.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Norway had by virtue of the Elementary Schools Acts and the Abnormal Schools Act established a system of segregation that classified students into three groups: normal school pupils, special school pupils and the non-educationally competent pupils. An institutional system that would embrace all would gradually be developed. But at the same time this system was beset by inconsistencies in regulation and organization, which could make a big difference in how children were treated. Gradually as the institutions were established, a general need emerged for testing and measuring children’s mental condition and level of ability, so that they could be classified and be allocated into the right place in the system. For example, measurement of a student’s intelligent quotient (IQ) was developed by Binet and Simon (1905), who worked from the French Ministry of Education, just after the turn of the century. The objective was to identify children with intellectual impairment and their level of intellectual deficiency. On the basis of their IQ and level, they could be placed in special classes with tuition adapted to suit their needs. The tests rapidly won recognition as the best tool in the task of separating the individual student groups from one another. It was thought that children’s intelligence could be measured purely in terms of ability, but that their mind, which indicated their moral level, could also be assessed.

It was not many years before the institutions under the two laws came in for sharp criticism from the public, in both literature and professional contexts. Initially, there were criticisms of abuse and mistreatment, lack of staff and resources and degrading living arrangements, primarily issues of human and material shortcomings. But soon people were not just asking about the material and resources aspects of the operation but also about the professional justification for the institutional placements. Several big cases were brought before the courts (Thuen, 2002). The revelations in these cases triggered a broad public debate about the work of the various institutions. For instance, they were accused of a lack of love and affection and a tough regime, and at worst of being concentration camps for children. Prominent politicians and members of the Government also voiced strong criticism. In practice, however, the criticism did not have much effect, investigations and official reports show that abuse and mistreatment of children continued on a significant scale right up to the 1970s (NOU, 2004, p. 23).

In the 1930s another form of criticism was expressed based on empirical and professional research (Arctander & Dahlstrøm, 1932). Arctander and Dahlstrøm reported that the research showed a high level of recidivism among children placed in institutions for children with behavioural difficulties or criminality. Furthermore, half of the boys in these institutions had committed criminal offences in the years immediately after being discharged and the rate of recidivism increased with the passing of time after they left. Also, compared with children in foster homes, the rate of recidivism of children from institutions was up to three times as high. In addition, psychiatric studies of institutionalized children conducted at the same time showed that: large groups suffered from various forms of mental disorders; and many of these children were also IQ tested and labelled as ‘backward’. In short the institutions had failed in everything from the admissions procedure to the educational content and outcome.

The Era of Segregation: In the Best Interests of the Child (1950–1975)

The period after the Second World War was dominated by a strong focus on the development of the welfare state. The Nordic welfare state model became the Norwegian strategy. The Nordic welfare state model, dominated by a social democracy, focused on universalism by giving equal benefits and services to all citizens regardless of the status of the family or market. The development of a good school system was in this framework important, and all children had the right to education.

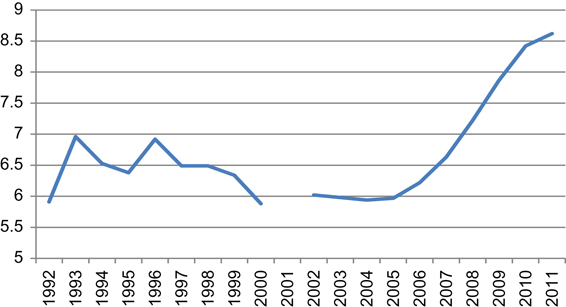

In 1951, Norway introduced the Special Schools Act, replacing the old abnormal schools and expanding the field of practice for special needs education. This law now applied to five groups of persons with disabilities, where previously there had been three. The individual groups were also extended. Where the old law included blind children, the new one would apply to the blind and the visually impaired. Likewise for the deaf; the new law included the deaf and hard of hearing. As well as these two groups, the law would apply to children with mental impairments with speaking, reading and writing difficulties and children with social behavioural difficulties, which previously fell under the Child Welfare Council Act and child protection. Terms like ‘educationally subnormal’ and ‘retarded’ were replaced by the collective term ‘mentally impaired’, which indicated that they should be the focus for the professional educational experts, while the other mentally impaired were brought back into the fold of the medical profession (Korsvold, 2006). At the same time, Norway got into a two-pronged system for special needs education; alongside separate special schools, special needs education could also be given as extra tuition in normal schools. The system expanded sharply in the decades to come. For example, in 1950, 1,500 students were received extra tuition in primary and lower secondary schools while in 1975 the number had jumped to 46,000 (SSB, 1975), or around 8 per cent of all students. Then special schools tripled during the period. The peak year was in 1978, when Norway had 100 special schools in the country with a total of 3,700 pupils (SSB, 1994).

Under the two-pronged system, special needs education was distinctly segregated during the years 1950–1975. It was an intentional policy, thus expressed in a Ministerial Recommendation in 1849: ‘A system must be devised so that pupils who belong in special tuition classes can be separated as soon as it is advisable’ (Samordningsnemda for skoleverket). The old system would be modernized, but without letting go of the diagnostic philosophy of segregation. The terms ‘special schools’ and ‘special needs teacher’ were introduced and brought into use a few years before the Special Schools Act was introduced (Ravneberg, 1999). The teachers in the various special schools were about to move closer and the use of the generic term ‘special needs teacher’ can be interpreted as a desire to define a common professional status. It was to be the introduction to an epoch defined by professional action and an increasingly professional approach.

One significant aspect of the new segregation policy was that the various groups of disabled children were not mixed together within the institutions which had particularly been the case in the previous era. The diagnosis of children using different tests, primarily IQ tests, was central to this work (see Table 1). The problem with this type of testing was that it set IQ boundaries between the various groups. Scales for division of intelligence according to IQ were developed based on international research, but the borderline cases were and still are problematic. Because of these borderline cases, teachers in normal schools, auxiliary schools, and special schools needed to discuss where borderline students were to be placed (Ravneberg, 1999). Finally, there were also pupils with ‘character defects’ which made them unsuitable for admission to special schools. These pupils had to be separated from the special school system and sent to separate homes for the educationally subnormal but it was not clear what ‘character defects’ entailed. In hindsight due to these aspects, many children were wrongly placed in this heartless system of segregation.

Table 1. Proposed Division of Students in the Norwegian School System in 1948.

| |

IQ |

Percentage of Student Population |

| Normal school |

Above 90 |

93.75 |

| Support/help school |

66–90 |

4.9 |

| Schools for mentally retarded |

41–65 |

1.1 |

| Nursing home |

0–40 |

0.25 |

Source: Developed from Ravneberg (1999).

It may be debated whether special needs education in the years directly after the war was anything more than a pure organizational convenience. Were the activities based on educational theories and principles? A common point of reference appears to have been the Swiss psychologist, teacher of the deaf and later a professor of mental health education, Heinrich Hanselmann (Thuen, 2008). A central theme to his theory was to bring the treatment of the deaf, educationally subnormal, those with speech impediments or nervous conditions, socially difficult and unprincipled children under one heading. The common feature was that they all suffered from defects in personal development that advocated a special therapeutic educational approach, an overall view of their human spiritual life. The old term ‘abnormal’ was replaced by ‘developmentally impaired’, an expression that is found in the Norwegian reform philosophy at the end of the 1940s. Therapeutic educational theory focussed on the upbringing of children, not their health, which fell within the medical profession and this is where it would be necessary if it would separate the children. The general impression is however that up to the 1960s special educational needs teaching both in primary and lower secondary schools and in the special schools largely muddled along on the basis of trial and error, without any foundation in a tradition of scientific knowledge (Haug, 1999). The knowledge was primarily based on an exchange of practical experience. The content of special needs education would therefore be mainly driven by practical experience.

To increase the level of professionalism of the special education support system, the national college of special teacher training was established in 1961. Training of special teachers developed slowly from short courses in the 19th century, into a 2-year study course offered by the special teacher training college from 196l. The first year offered an introduction to five areas of special education: intellectually impaired, blind, deaf, language and speech problems, and behavioural problems. The education of teachers focused on practical challenges faced by teachers in the special schools. The second year offered a specialization within one of the five areas of specialization. The establishment of a special teacher training school led to an increased awareness of the need to also develop special education as a research area as part of the training and development of special teachers. This focus on research led to the first MA course in special education in 1976, and the PhD in special education was established in 1986. The special teacher college became part of the University of Oslo in 1990.

In the 1970s, several other colleges were given the opportunity to offer the first and second year of training to special teachers. This development came, as discussed later, at the same time as the normalization ideology (Wolfensberger, 1972) became a political factor in education. As a result of this, the new colleges for training special education teachers divided themselves into more or less two directions: one group following the system in the already established national special teacher training school and a second group with a clearer support of the normalization ideology and later integration.

The Era of Integration: Social Critique and Normalization

Not until the mid-1960s can we detect the signs of a political shift in the direction of a policy of integration. It was now recognized ‘that the objectives of the special schools are in principle the same as for normal general education schools’ (St.meld 42, 1965–1966). The separated children had a ‘need for the same broad general educational, cultural and social development objectives as other children and young people’. These were fundamentally new perspectives in special school policy, derived from ‘experience and new developments in psychology, psychiatry and sociology’, as it was said. Special needs education had to look after ‘the person behind the handicap’ (St.meld 42, 1965–1966). The separated children must not ‘get used to thinking of themselves and their peers as patients, cases or clients’. It is true the term ‘deviants’ was still used in referring to children with disabilities, but the causal pattern behind their ‘deviant condition’ was assumed to be more complicated and complex than had been believed from previous knowledge. Reference was made to England, where special educators’ attention focussed on ‘children at risk’, and the need for supervision and observation of children assumed to be in the danger zone for ‘dysfunctional development’. An effort was made to get away from the ‘old’ segregating methods and the way was opened for new, extended forms of understanding. In the first instance, the shift was expressed in a cautious scepticism in regards to institutions. For example, there was an argument in favour of using more day schools as opposed to boarding schools in regards to the further development of the special schools system. But in a broader perspective they were looking for a new type of expertise, an expertise based on three aspects, as envisaged by the Spesialskolerådet (Norwegian Council for Special Schools): educational diagnosis, educational treatment, and educational research (St.meld 42, 1965–1966). The aspects looked promising. It was essential for the research to be based on practical experience. Special needs educational research and special needs educational practice should be mutually stimulated by long-term cooperation.

The concept of integration entered the debate about the further development of special needs education at the end of the 1960s when the so-called Blom Committee was appointed in 1970. In spite of the ideological shift promoted by the Government in the mid-1960’s criticism of the system had not abated. There are several explanations for the negative reactions. They are partly due to the lack of political vigour on the part of the Government, and partly the treatment the children in the institutions could be exposed to. A new era was approaching. It started in 1975, when the Special Schools Act was integrated in the Primary and Lower Secondary Schools Acts. The long tradition in special needs education would now finally be replaced by ‘integration’. Science had brought a new sensitivity to the child’s inner life and psyche that indicated that the security of the child was a vulnerable and delicate quantity. With their alienation and formalism the institutions represented a danger for children. The question was no longer whether the institutions were beneficial and effective for society, but also whether they were in the ‘best interests of the child’. The Blom Committee proposed one common school law for all children. This was effectuated in 1975 (St.meld 98, 2009). This common school law emphasized that all children should have the right to education based on their abilities. The right to special education should not be connected to a medical situation or age, but to the pedagogical needs of each child. The principle of education to all children gave also the last group, severe mentally disabled children, the right to education. The main focus on integration and the goal of integration was accordingly:

(a) all should be part of a social community,

(b) all should have a share in the goods of the community,

(c) all should have the responsibility for tasks and obligations in the community.

The goal of integration was according to this committee to reduce barriers on human, social, and organizational levels. People with disabilities should have the same rights as everybody else to an education to foster personal, academic, and social development. How this equality should be reached was still much to be debated. The committee proposed a mix of both local support in ordinary schools and a national special school system (Kiil, 1981). This mixed support system continued to be offered in Norway for over 20 years, but the process of integration had begun.

The academic discussion in the same period was divided into two areas. As already presented, it had a strong focus on the scientific basis for the special education profession. This development was mainly within the already established categories of special needs that dominated the second year of the national teacher training college. The second area was established as part of the critique of the segregated strategy – the perspectives of normalization. The concept of normalization related to people with disabilities did partly exist as an organizational concept in the Nordic countries just after the Second World War, however, its development as a democratic and political concept took place in the 1960s by those at the forefront; Bengt Nirje from Sweden and Niels Erik Bank-Mikkelsen from Denmark. Bank-Mikkelsen first discussed the concept in 1959 (Biklen, 1985) but the word itself was first authored by Nirje (1969, 1985). Their perspectives on normalization had an international impact in the late 1960s, and these thoughts also brought new aspects into the special education debate in Norway by particularly emphasizing that the area of education must be related to the general social principles of the community. This focus on normalization as part of the general social development gave strong support to the goal of integration. Compared to several other Western countries the development of integrating children and adults with disabilities had taken place relatively slowly. However, in the late 1980s this changed, and already in 1993 most of the nursing homes and national special schools were closed down (Tøssebro, 2010). All children were then to have their education in the normal school and adults were to have the possibility to live a normal life as participants of the local community. Vislie (1995), one of the main Norwegian contributors to the academic discussion on integration, points to two strategies of integration that were developed during the 1970s and 1980s. The first strategy was related to the development of the special educational area to meet the new demands of integration. The second strategy was to reformulate the regular school system to meet an increased diversity of students.

The changes made in the Norwegian school system in the 1970s and 1980s reflect the first strategy described by Vislie (1995). The special school system was slowly reduced and almost all special schools were closed in 1993. Only a few schools for pupils with hearing and visual problems remained. The next strategy – the reformulation of the regular school system – became the next challenge for the special education system in Norway. It must be added that these radical changes in the late 1970s came at the same time as Norway became an oil-producing nation. Norway’s wealth grew extensively from the mid-1970s, and with this wealth came both the international wave of new ideas of how to meet diversity and the financial possibility to carry through and pay for new reforms.

The Era of Inclusion: The Last Phase of Norwegian Special Education?

The goal of integrating students physically into the ordinary school system was more or less fulfilled in 1993 – one year before Norway ratified the Salamanca Statement. The closing of special schools and the strong drive towards integrating students with special needs in the 1980s and the early 1990s meant that the ratification of the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994) did not lead to any new national strategy when meeting children with special needs. The process of integration had already fulfilled most of the organizational strategies of the Salamanca Statement. However, for the concept of inclusion to mean more than just integration, the academic field of education presented definitions of this concept that emphasized the change that inclusion meant. In the Norwegian framework the definition presented by Peder Haug covers the Norwegian understanding of inclusion. An inclusive educational environment shall according to Haug (2003) focus on increasing fellowship among students, giving all students the possibility of participation as part of a process of democratization, and on top of this giving all students the necessary support so that they benefit from the education offered. The Norwegian understanding of inclusive education is as seen, not about integrating students in ordinary education, but about the transformation of teaching so that it supports all learners. In other words, it was the second aim of integration presented by Vislie (1995) that became the dominant focus for the Norwegian inclusion debate. A central reason for this focus was the high emphasis on normalization that led to the changes in the early 1990s. Theoretical perspectives of inclusion seem to follow the same line of argument and advocate for normalization would then also support the new concept of inclusive education. The political area had a strong drive towards fulfilling the normalization reform, and in this context special education was understood as not compatible with the goal of inclusion. In other words, the choice of this strategy meant that the approach of special education was reduced, and Norwegian educational policy from the mid-1990s was highly influenced by the criticism raised by advocates for inclusive education and the goal was to reduce the amount of special education to a minimum.

REFERENCES

Aas, O. E. (1954). Public care for mentally retarded in Norway from 1870–1920. Oslo, Norway: Hovedfagsoppgave, Universitetet i Oslo.

Arctander, S., & Dahlstrøm, S. (1932). The status on children in public care from 1990–1928. Oslo, Norway: Olaf Norlis forlag.

Bachman, K., & Haug, P. (2006). Research on adapted education. Volda, Norway: Høgskulen i Volda.

Befring, E., & Tangen, R. (2008). Special education. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen.

Biesta, G. (2004). Against learning: Reclaiming a language for education in an age of learning. Nordisk Pedagogikk, 24(1), 70–82.

Biklen, D. (1985). Achieving the complete school: Strategies for effective mainstreaming. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Binet, A., & Simon, T. (1905). Methodes nouvelles pour le diagnostic du niveau intellectuel des anormaux. L’Annee Psychologique, 11, 191–244.

Froestad, J. (1995). Professional discourses and public policy in the care for the handicapped in Scandinavian in the 1980s. Dr. Avhandling, Rapport No. 34. Bergen, Norway: Institutt for administrasjon og organisasjonsvitenskap, Universitetet i Bergen.

Froestad, J. (1999). Normality and discipline. In and S. Meyer, & T. Sirnes (Eds.), Normality and identity formation in Norway (pp. 76–98). Oslo, Norway: Gyldendal.

Gallagher, D. J., Heshusius, L., Iano, R. P., & Skrtic, T. M. (2004). Challenging orthodoxy in special education: Dissenting voices. Denver, CO: Love Publishing.

Government of Norway. (1881). Abnormal Schools Act of 1981. Oslo, Norway: Parliament of Norway.

Government of Norway. (1896). Children Welfare Council Act of 1896. Oslo, Norway: Parliament of Norway.

Government of Norway. (1951). Special Schools Act of 1951. Oslo, Norway: Parliament of Norway.

Government of Norway. (1975). Primary and Lower Secondary Schools Act. Oslo, Norway: Parliament of Norway.

Government of Norway. (1997). Norwegian curriculum plan of 1997. Oslo, Norway: Parliament of Norway.

GSI Norway. (2013). The schools information system. Retrieved from https://gsi.udir.no/. Accessed on December 31, 2013.

Haug, P. (1999). Special education in primary school: Fundamentals, development and content. Olso, Norway: Abstrakt forlag.

Haug, P. (2003). Qualifying teachers for the school for all. In and K. Nes, M. Strømstad, & T. Booth (Eds.), Developing inclusive teacher education (pp. 34–51). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hausstätter, R. (2013). The twenty percentage rule. Spesialpedagogikk nr 6.

Karlsen, G. E. (2005). Norwegian teacher education, a historical perspective. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift nr, 6, 403–416.

Kiil, P. E. (1981). Legislation for special education after 1945. Oslo, Norway: Pedagogisk forskningsinstitutt.

Korsvold, T. (2006). The value of the child: A childhood as mentally retarded in the 1950s. Olso, Norway: Abstrkt forlag.

Ministry of Education. (2006). The knowledge promotion reform. Retrieved from http: //www.udir.no/Stottemeny/English/Curriculum-in-English/_english/knowledge-promotion---Kunnskapsloftet/. Accessed on December 31, 2013.

Ministry of Education and Research (MER). (2012). Retrieved from http://www.regjeringen.no/en/dep/kd/news-and-latest-publications/News/2012/regjeringen-har-begrenset-privatskolene.html?id=686534

Mostert, M. P., Kavale, K. A., & Kauffman, J. M. (2007). Challenging the refusal of reasoning in special education. Denver, CO: Love Publishing.

Nirje, B. (1969). The normalization principle and its human management implications. In and R. B. Kugel, & W. Wolfensberger (Eds.), Changing patterns in residential services for the mentally retarded (pp. 179–195). Washington, DC: President’s Committee on Mental Retardation.

Nirje, B. (1985). The basis and logic for the normalization principle. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 13, 65–68.

NOU. (2004). Care institutions for children: National evaluation of the institutions from 1945–1980. Olso, Norway: Ministry of Education.

Nygren, A. (1966). Eros och Agape. Stockholm, Sweden: Aldus/Bonmers.

Ravneberg, B. (1999). Discourses of normality and professional processes. Rapport No. 69. Bergen, Norway: Institutt for administrasjon og organisasjonsvitenskap.

Richardson, J. G., & Powell, J. J. W. (2011). Comparing special education: Origins to contemporary paradoxes. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Samordningsnemda for skoleverket, VII. (1949). Olso, Norway: Kirke-og undervisningsdepatementet.

Simonsen, E. (1998). Science and professional battles: Teaching of deaf and mentally retarded in Norway from 1881–1963. Dr. Avhandling. Oslo, Norway: Det utdanningsvitenskapelige fakultet, Universitetet i Olso.

SSB. (1975). Educational statistics. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Education.

SSB. (1994). Statistics Norway. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Education.

St.meld 42. (1965–1966). On the development of special education schools. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Education.

St.meld 98. (2009). Special education. Oslo Norway: Ministry of Education.

Thuen, H. (2002). In the place of parents, child and institutions from 1820–1900. Oslo, Norway: Pax.

Thuen, H. (2008). About the child, upbringing and care through history. Oslo, Norway: Abstrakt forlag.

Tøssebro, J. (2010). What is disability. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

UNESCO. (1994). Salamanca statement and framework for action on special education needs. Paris, France: United Nations.

United Nations. (1975, December). Declaration on the rights of disabled persons. General assembly resolution 3447(xxx). New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations. (2006). United Nations treaty collection 15. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. New York, NY: United Nations.

Vislie, L. (1995). Integration policies, school reforms and the organization of schooling for handicapped pupils in Western societies. In and C. Clark, A. Dyson, & A. Milward (Eds.), Towards inclusive schools? (pp. 42–53). London: David Fulton.

Werner-Putnam, R. (1979). Special education – Some cross-national comparisons. Comparative Education, 15(1), 83–98.

Wilson, D., Hausstatter, R. S., & Lie, B. (2010). Special education in primary school. Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget.

Wolfensberger, W. (1972). The principal of normalization in human services. Toronto, Canada: National Institute on Mental Health.