EARLY ORIGINS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION

Communal Guardianship for Persons with Disabilities

In pre-Christian times pagan Slavs showed tolerance toward persons with disorders or injuries. At the end of the 10th century, a system of church-based charities began to emerge in the Kievan Rus’,1 then an influential European power. The state laws defined the groups of persons in need of help and those obligated to care for them. The adoption of Christianity in AD 988 with the extensive building of temples, churches, and monasteries started the age of charity work for persons with disabilities, which was institutionalized and regulated by the national legislation of the time. The monasteries maintained special institutions that provided care to such persons and, additionally, taught them basic literacy and handicrafts. Thus, as evidenced by historic and archive records, in the Kievan Rus’ children with disabilities were surrounded by the atmosphere of care and sympathy.

To a large extent the evolution of teaching ideas and education in Ukraine was influenced by the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the humanist ideas of the Enlightenment. This closely intertwined with the formation of cultural and ethnic solidarity, raising to a new level the self-awareness of the Ukrainian people as a distinct nation and reaffirming the uniqueness of its model for the education of the younger generation. In the 16th century literacy became more or less universal in the Ukrainian lands. Schools had orphanages attached to them for orphans and children with various disabilities under the patronage of the community (Taranchenko, 2013).

During the 17th and 18th centuries, with the strengthening of secular authorities, another form of care became widespread, which was provided by the state, alongside church-based care and private charities. The Agency for Poorhouse Construction, founded in 1670, oversaw these institutions that became homes for old people with physical disabilities and children. Some of them had special divisions that served orphaned children, blind children, deaf-mute children, and others together, where they were observed and studied, taught basic work skills, and skills for independent living in the community (Taranchenko, 2013).

At the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th century institutions and departments appeared that were directly responsible for charity work, as a new phenomenon in the evolution of social guardianship in the Russian Empire. The first and the most influential was the Office for Empress Maria’s Institutions which oversaw virtually all social care institutions in the country: hospitals, schools, shelters, asylums, poorhouses, etc. (in the late 1890s there were almost 300 charitable societies and institutions). Ninety-eight percent of school-age children did not receive any education in the Russian Empire (Siropolko, 2001; Taranchenko, 2013). For this reason (lack of a compulsory education system) and the existing social, political, and economic situation, the country had no educational network for persons with hearing, visual, mental, and other disabilities.

First Private Institutions for Different Categories of Children with Disabilities

From the start of the 19th century, riding on a tide of enthusiasm for education in Ukraine, physicians, teachers, and public leaders increasingly paid more attention to the education of persons with disabilities. Segregated private schools were founded for deaf-and-blind children, and those with intellectual disabilities (10 schools for persons with hearing disabilities, 6 for children with visual disabilities) which followed a rather progressive instructional approach, matching western European practices. For example, some schools had pre-school units, offered well-organized vocational training programs, and applied the latest teaching methods. The instructional process was founded on the principles of nature-aligned education, continuity of teaching and learning (beginning from pre-school age), and drew on the individual characteristics of children to guide the selection of relevant teaching strategies. For instance, schools for children with hearing disabilities, in spite of the predominant speech-based instruction, used other modes of communication (sign language, finger-spelling) at the initial stages and when necessary to facilitate learning and create a supportive and natural environment for children (Kulbida, 2010; Taranchenko, 2007). Ukrainian schools were organized according to a family pattern: life and learning at school were structured in such a way as to help students acquire a broad range of skills for independent living in a wider community. Ukrainian teachers believed that the main purpose of schooling was to prepare people with disabilities for independent life in the community, and therefore, in addition to academic targets, they paid a lot of attention to their vocational training. This added a unique flavor to Ukrainian special education. The growing number of schools for persons with disabilities and the broader range of disabilities they served created the need to differentiate the student body. In the 19th century medical and educational professionals made considerable efforts to organize a system of education for persons with disabilities and carried out theoretical research and field studies to explore specific teaching approaches for different categories of children. The cohort of academics and practitioners engaged in the discussion of various issues related to assessment, teaching and learning, character building and socialization of children with developmental disorders included names that are now famous in Ukrainian education circles as well as, in some cases, internationally: Tarasevych (1922), Vladimirskyi (1922a, 1922b), Kashchenko (1910, 1912), Sikorskyi (1904), Maltsev (1902, 1910), Vetukhov (1901), Grabarov (1928), Leiko (1906), Sokolyanskyi (1925), Shcherbyna (1916), and others.

Regulatory Formalization of Education for Persons with Disabilities

After the collapse of the Russian monarchy in 1917, Ukraine had a number of different government and social-political structures (Central Council (Tsentralna Rada), Hetmanat, Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR), Directorate, Communist Party of Ukraine, Soviet government). In 1919 the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic adopted a number of national policies (decrees) on organizing public education in the Republic. According to these decrees, schools for children with disabilities became a part of the general state system of public education. Obviously, the turbulent politics and social hardships had an adverse effect on the existing schools for persons with disabilities. Moreover, some of these schools had to close down due to the lack of funding, staff, etc. The difficult social, economic, and political situation continued to persist (lack of social stability for people to return to normal life, warfare, destruction of infrastructure, hunger, and repressions). During this period, the number of homeless children and orphans went up to 1.5 million (Likarchuk, 2002; Taranchenko, 2007).

At the same time, it should be noted that during that brief period of national independence from 1917 and in the 1920s, the national system of education acquired its theoretical and teaching framework, which was based on democratic principles, and domestic and international best practice. This became possible because of the administrative autonomy that Ukraine enjoyed for some time in education matters (Ukrainian and Russian education policies were not associated with each other).

The structures and working protocols of the education system for persons with disabilities were formalized in the regulatory act “Declaration of the Social Education Subdivision” of 1920 (People’s Commissariat of Education of USSR, 1922). The directives in this act were research-based, humanistic, underpinned by the concept of children’s rights and in tune with the most provisions of modern education laws and regulations, which indicates the advanced professional knowledge and progressive views of the Ukrainian developers of this policy. The Declaration stipulated that best practice from the assessment services (monitoring and placement offices) were to be disseminated across the republic and incorporated into the education system for persons with disabilities. They were an early prototype of the Psychology, Medical, and Pedagogical Consultations (PMPC) and support services that continue to the present day and are described in greater detail below. Ukrainian academics and practicing teachers gave the highest priority to the organization of education for children and youth with disabilities such as: the need to ensure compulsory universal pre-school education; differentiation of children and setting up separate schools for each category; creating specialized assessment institutes; forming special education departments at universities and founding institutes for teacher training; ensuring the continuity of education and adequate medical services; providing vocational training to youth with disabilities and creating vocational training schools for them.

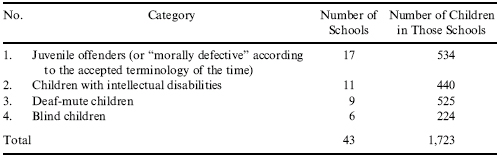

Table 1 gives a brief statistical overview of the school network established for children with disabilities (i.e., “defective children” or “defective childhood” according to the terminology of the day) in 1924.

Table 1. Schools for Children with Various Impairments and Student Numbers in 1924.

Development of Differential Diagnosis and Educational Intervention

The key question during those years was how to identify “defective” children and study the nature and pattern of their development, how to explore ways of providing social, medical, pedagogical, and psychological support. In addition, research in medicine, psychology, and pedagogy boosted the advancement of the new academic field of pedology (child development) that encompassed a multitude of teaching, psychological, medical, and social issues and combined different areas of study. In the 1920s, pedology became the dominant experimental science about the child. It drew on the theories of Decroly, Dewey, Montessori, Lay, Meumann, Key and laid the foundations for further pedagogical research by Ukrainian scholars and teachers (Vladymyrskyi, Zaluzhnyi, Makarenko, Protopopov, Rusova, Sokolyanskyi, Tarasevich, Chepiga, and others), who were inspired by the concept of progressive education. These ideas were the most conducive ones to create supportive settings to facilitate learning and the all-round development of children with disabilities.

Of particular interest are studies that explored approaches to the classification of children with disabilities. The first publications on this issue had a significant impact, and the titles and content of the articles reflect the thinking of the time: “Classification of defective children” (Tarasevych, 1922), “Defective individual in the context of social education” (Vladimirskyi, 1922a), “Person in the general change of events” (Vladimirskyi, 1922b).

A new approach to the classification of children with disabilities was proposed by Tarasevych (1922), reflecting his long-term studies. He assumed that children with deficiencies in psychological and/or physical development make up the group of “defective children.” In his view, the group also includes children without any disabilities, but with specific traits in their psychological-physical organization or health conditions which impede a person’s development. Tarasevych emphasized in particular that different types of disability were not equivalent socially and pedagogically. Based on this, Tarasevych identified three groups of “defective” children: children with physical disabilities, children with sensory disabilities; and children with neuropsychic disabilities. Even before the theoretical reasoning by Vygotsky (1924), he deliberated on secondary manifestations of disabilities and the range of factors that complicate the disability pattern. In Tarasevych’s view, the diversity of the types of neuropsychological disorder depends on a number of complicating factors (adverse environment, upbringing, various health conditions, etc.). Recognizing the dependency of different types of primary neuropsychological disorder on the localization, nature, and degree of organic disorders in neuropsychological domain, he distinguished, specifically regarding intellect, four degrees of disability of increasing severity. He argued persuasively that a delay or disorder in mental development had different causes and discriminated between children with mental disabilities, educationally neglected children and children with developmental delays caused by various unstable conditions which manifested themselves at an early age and influenced the child’s development (Tarasevych).

According to Tarasevych (1922), the purpose of educational and psychological assessment is to identify the causes of the disability that is the primary disorder responsible for the disability. Thus assessment might involve a medical and psychological examination of the child as well as a review of his/her prior experiences and family background. This assessment data would subsequently be used to select appropriate educational approaches and instructional strategies for such children. He also believed that in selecting learning content and instructional strategies it was essential to differentiate secondary symptoms, which are due to adverse effects of the surrounding environment and poor education, and the primary disorder caused by congenital or acquired organic disorders. This idea formulated by Tarasevych became fundamental for implementing differential assessment, designing research into different types of disabilities, and in selecting educational intervention strategies.

Tarasevych (1922) also stressed the significant diversity within each category of children with disabilities. He postulated that an individual’s psychological constitution, the structure of disorder within the intellectual, psychic, and education development will be different in each individual case and, consequently, different educational interventions may be required to compensate for the disability of a particular child; likewise, the prognosis for further development may vary from one child to another.

These insights into the role of different factors in the structure of the disorder and how they influence child’s development, enabled Tarasevych (1923) to suggest specific approaches to teaching and learning, and formulate the goal, objectives, and methods of special education. The above concepts are also present in later research conducted by other academics. For example, they are reflected in Boskis’ (1959) thinking, specifically in her psychological-pedagogical classification of children with hearing disabilities that is described in more detail below.

Another noteworthy piece of research during the same period is that of Vladimirskyi (1922a, 1927), who also emphasized the need for a comprehensive study of disabilities. In particular, he pointed out that “defectiveness” in a person is conditioned by quantitative and/or qualitative deficits in their experience, which becomes incomplete or distorted in nature. Hence, it is necessary to study a child thoroughly and in every aspect, compare his/her performance with the data about inherited and acquired experiences, determine what was missing in their past experience in order to gradually fill this gap in the course of education. So, academics and practitioners focused on studying the child with a disability and their social environment in order to influence the child’s experience and transform that environment to support his/her development (Sokolyanskyi, 1928a, 1928b; Tarasevych, 1927, 1929; Vladimirskyi, 1927).

The main functions of the medical and pedagogical offices included a review of child’s medical history data, clinical assessments, examination of the central nervous system, physical development, etc. During that time the first attempts were made to determine biological, constitutional, psychological and social factors at the heart of a child’s disability and to design therapies and teaching strategies to influence these factors.

The works by Ukrainian researchers published during that time period underlined the need to start medical and pedagogical preventive measures and special education interventions from an early age. They presented findings from experimental research involving clinical studies of children with intellectual and psychological disabilities; considered the issues of etiology and anatomic-morphological disorders that cause mental retardation. Based on these findings the authors generally concluded that mental retardation is a typical, but not the only, feature of impaired psychological development of a child with the respective disability. They went on to state that a central nervous system disorder, being the cause of mental retardation, quite often affects the sensory-motor mechanisms of mental activity, as well as the emotional and volitional sphere.

In research, priority was given to somatic-neurological, psychological, and pedagogical aspects to identify the patterns of a child’s psychological development; explore and record the specific features of the disability and compensatory abilities of a child with mental retardation. They indicated the need to study children with intellectual disabilities in the dynamics of their development as part of teaching and learning, which is vital for understanding individual differences. These ideas were fundamental for constructing a research-based framework for the new education system and for designing the curriculum and a new set of teaching approaches for students in special schools for children with intellectual disabilities.

In 1921 two instructors from the Kharkiv School for the Blind – Przhyborovska and Slyeptsov – created a Ukrainian version of Braille’s point ABC that made it possible for children to learn in their mother tongue. The leading Ukrainian experts in the education of blind children (Leiko, 1901, 1906, 1908; Shcherbyna, 1927; Sokolyanskyi, 1928a, 1928b; and others) developed teaching strategies for different groups of students with visual disabilities (including deaf-and-blind children).

In their efforts to ensure that children with mental and physical disabilities received specific training to prepare them for independent life in the community and provide them with the necessary social skills, Ukrainian academics initiated a wide-ranging program of theoretical and methodological studies to look into the general patterns and peculiarities of a child’s development. These studies were conducted by the employees of medical and pedagogical offices. To this end they were gathering and analyzing data on the mental and physical development of children, exploring various educational intervention strategies that helped master the school curriculum and acquire practical skills. Every potential candidate for placement in a special school underwent the assessment process. For this purpose, medical and pedagogical offices designed tools for medical, psychological, and pedagogical assessment.

In the 1920s, a distinctive assessment network was established in Ukraine, consisting of medical and pedagogical units, observation and placement offices, special collector institutions, medical and pedagogical offices, and research and pedological centers. The network operated all over the republic and became an integral element in the structure of the national education system for persons with disabilities. It may be described as the prototype of the contemporary support services provided to students with disabilities in schools. At that time, the network performed all the relevant functions: statistical recording; assessment (both short-term and long-term in specially organized classrooms and schools); research; consultation and advice (for parents, regular and special school teachers); professional training and awareness-raising (arranging training courses, practical internships, conferences and seminars); design of research-based guidelines and curriculum materials, diagnostic tests and techniques (e.g., related to occupational guidance); development of integrated initiatives, psychological and didactic principles of comprehensive education for urban and rural schools (separately); study of children’s groups, etc. In addition, Ukrainian scholars and practitioners experimented with placing children with disabilities in the same classrooms with their typically developing peers in regular schools (although society was not yet ready for it). Methodological guidelines were developed for regular school teachers to equip them with specific strategies and techniques that are effective with students with disabilities. The achievements of this network later made it possible to differentiate within and further expand the regular education system and the system of education for persons with disabilities as a separate part of it. This is evidence of a quite original and progressive approach to establishing a national system for the education of persons with disabilities at that time and demonstrates the novel way of thinking within the cohort of Ukrainian scholars (Vladymyrskyi, Grabarov, Sokolyanskyi, Tarasevych, Sikorskyi, Kaschenko, Leiko, and many others).

At the center of the Ukrainian education system was the idea of social education for children from 4 to 15 years of age. This approach was based on the increasing influence of the community on the child’s life. It included healthcare provision, and education and character development in the course of academic learning that was combined with extra-curricular activities. This model was underpinned by national traditions and relied on the use of best national and international educational practice in schools. A children’s community was envisioned as the main type of learning setting for children (this format of “social education” was chosen specifically to address the pressing issue of homeless and orphaned children). Such a community would combine different types of learning and extra-curricular facilities under one roof (pre-school, school, and extra-curricular center). The plan was to provide social education not just to orphans, but to cover all children, including those with disabilities. The existing institutions for children with disabilities were in fact implementing this model in practice, so they were to be smoothly integrated into this new system. This period was crucial for establishing the regulatory framework for education. Following the Resolution “On introducing compulsory universal primary education in Ukraine” adopted by the Central Committee of the Communist Party in 1930, universal compulsory education became a legal norm. In 1931 the People’s Commissariat for Education of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic passed the Resolution “On introducing compulsory universal education for children and adolescents with physical defects, mental retardation and speech defects” (1931).

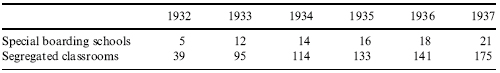

At the start of the 1930–1931 school year, Ukraine had 25 special schools for children with mental disabilities including: 6 special non-residential schools, 17 special boarding schools; 2 children’s communities (4,470 children) and 1 pre-school for children with speech disabilities (the school only opened in 1937, since before that speech disabilities were addressed through a clinical approach and fell under the responsibility of professionals with medical qualifications, while the psychological and pedagogical dimensions of speech support were just emerging). In total, 7,628 children aged between 6 and 13 were identified as having hearing disabilities, while only 1,100 of them were receiving education (Likarchuk, 2002; Siropolko, 2001; Taranchenko, 2013). In 1932, that number increased to 8,400, and 24 schools served 1,445 students (including segregated classrooms in regular schools). Children with visual disabilities were placed at special boarding schools for the blind or separate classrooms in regular schools (see Table 2).

Table 2. Schools for Children with Visual Disabilities, 1932–1937.

During that time, the unification of the education system was underway in the USSR which marked the transition to the administrative command methods in education management, led to its final centralization and set a new course – toward a Soviet education system where all teaching and learning was indoctrinated with Soviet ideology. In those years and later the majority of Ukrainian scholars were declared “enemies of the people” (on various charges) and their works were destroyed as “anti-Soviet.” As a consequence, their ideas and know-how regarding differential assessment, specific teaching and learning strategies for different age groups of persons with disabilities were practically rejected; the prototype of the service network (medical offices, collector institutions, etc.) that existed only in Ukraine and offered support to children with disabilities in the course of their education was undermined; academic and experimental research centers that designed and piloted new tools and models, provided training and professional development to teachers were closed down. The policy paper “The second five-year plan: targets for defective childhood” (Direktyvy VKP(b) (Directives of the All-Union Communist Party), 1932) was adopted as a supplement to the Resolution “On introducing compulsory universal education for children and adolescents with physical defects, mental retardation and speech defects” passed by the People’s Commissariat for Education in 1931. It laid down the directions for special education teaching and the education system for children with disabilities in the Ukrainian USSR. This policy identified the Moscow Defectology Institute as the single authority in the field with the responsibility to design the theoretical framework for the education of this group of children. Since all policies of that level were construed as absolute commands, and given rather serious difficulties at the Ukrainian Institute of Physical Defectiveness in 1930s (that was later shut down), it was the academics from the Moscow Research Institute of Defectology who initiated studies into the development and education of children with disabilities (Direktyvy VKP (b) (Directives of the All-Union Communist Party), 1932).

The period between 1930 and 1941 saw the introduction of compulsory primary education and universal seven-year basic education. Universal compulsory education for children with hearing and visual disabilities was to be provided through the expanding network of special schools with increasing student numbers, the creation of separate schools for children and adolescents who were deaf, blind, had other hearing and visual disabilities (letter of instruction from the People’s Commissariat for Education of the Ukrainian SSR dated April 1934 “On expanding the network of schools for persons with physical defects, mental retardation and speech disorders in 1934 in the view of universal compulsory education for defective children”).

The years of the third five-year plan (1938–1942) were about preparing for and surviving the Second World War. The greater part of the national budget was channeled to the needs of the army, whereas education was funded residually and mostly from local budgets. Still, the school network continued to grow:

- During 1937–1938 Ukraine had 49 schools for children with hearing disabilities (5,281 students); 82 literacy schools were run for illiterate youth with hearing disabilities; 1 school for children with speech disabilities (100 students);

- In 1940 there were 65 schools for deaf children, 1 school for children with hearing disabilities (who became deaf from an older age) serving the total student body of 8,145; 4 schools for deaf-mute children had classrooms for students who lost their hearing at an older age;

- In 1941 the number of schools grew further to 83 schools for deaf children (9,419 students), 1 school for children with hearing disabilities (182 students), 3 pre-school children’s communities (200 children), 93 schools for adults (3,000 persons), 17 schools for blind children (957 students), 1 school for children with visual disabilities (182 students), 3 schools for children with speech disabilities (251 students), 4 schools for children with behavior problems (578 students).

During this period, Boskis (1959, 1969, 1972) and her team conducted research into psychological and physical development of children with hearing disabilities to design a new didactic model for their special education. Between 1920 and 1930, Boskis worked at the Jewish school for deaf-mute children (from 1931 – at the Institute for Experimental Research in Defectology under the People’s Commissariat for Education of the RSFSR; from 1944 – at the Defectology Research Institute of the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences of the RSFSR). She had extensive experience of observing and teaching diverse groups of students with hearing disabilities at that stage of her academic career in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. This enabled her to learn about the latest methods designed by the leading assessment and audiology experts, take part in the meetings of Ukrainian hearing specialists (Tarasevych, Sokolyanskyi, Vladymyrskyi, and others). This professional background prompted her interest in creating a pedagogical classification of children with hearing disabilities who were at the heart of her research. Considering that the majority of works authored by Ukrainian researchers were not published for ideological reasons, it was the Boskis (1972) classification that eventually became accepted and further promoted (Marochko & Hillig, 2003).

The pedagogical typology of children with hearing disabilities suggested by Boskis (1972) was based on certain general assumptions that describe peculiarities in the development of a child with impaired sensory receptors. She argued that in the case of a partial defect, in order to determine the nature and structure of development it is first of all necessary to: discriminate the norm from pathology; differentiate between total and partial defects; identify the unique secondary anomalies with impaired receptor partially functioning; study the conditions that determine peculiarities in the abnormal development of functions impaired at the secondary level; identify the techniques to help compensate for and adjust to the defect that may be applied to different forms of partial hearing disability; design tools to assess secondary defects as opposed to similar primary defects; etc. (Boskis, 1959, 1969, 1972). These principles made it possible to describe a category of children with partial loss of hearing (or hard-of-hearing).

With speech being the closest function dependent on the auditory analyzer, all studies on the development of the hard-of-hearing led by Boskis (1959) took into account the interaction between hearing and speech. She noted that impairments in speech development in a child caused by a hearing disability can be observed even with a hearing loss of 15–20 dB. Hence, it was suggested to use this measure as a conventional boundary between a hearing disability and normal hearing in a child. Using it to assess a hearing disability (the capacity for speech development with the respective degree of hearing) helped to find a solution to another problem – how to draw a line between deafness and significant loss of hearing in order to provide differentiated instruction for children. As the same time, Boskis (1969) observed that speech development depends not just on the degree of the primary disorder, but on a number of other factors as well: the age when hearing became impaired, the pedagogical environment created for the child after the impairment occurred, and his/her individual peculiarities. Taking all these other factors into account, a clear differentiation was made within deaf and hard-of-hearing groups to ensure an appropriate pedagogical environment and specially organized instruction. Deaf children were divided into two categories:

- deaf children with no speech (who lost their hearing at early age) who lost their hearing at an early age and did not acquire any speech skills;

- deaf children with speech preserved (who lost their hearing at a later age).

Two categories for children with partial hearing disabilities were proposed:

- hard-of-hearing children with well-developed speech and minor speech shortcomings;

- hard-of-hearing children with serious impairments in speech development.

Boskis (1972) suggested a conceptually new definition of the term “hard-of-hearing children.”

This psychological and pedagogical research revealed the dialectic interaction between biological and social factors in the development of child’s psyche. At the most fundamental level, it confirmed the importance of special speech instruction as a key factor for providing relevant developmental interventions in this category of children, helping them master the basics of sciences and live full lives in their communities. This research laid a theoretical foundation for further exploration of issues related to special education of children with partial hearing disabilities in the decades to come.

However, this period was also marked by a clash of theoretical views on the differentiation of children with hearing and speech disabilities. Over a period of 15 years, and simultaneously with Boskis’ (1959, 1969, 1972) research, Shklovskyi (1938, 1939) was establishing his theory of cortical deafness with the central assumption that many children with hearing disabilities have a cortical brain dysfunction. He argued that in all cases when hearing loss is combined with a profound speech disorder it was not just a loss of hearing, but a separate kind of disorder, whereby the hearing disability is the result of a cerebral lesion that disturbs the normal functioning of the cerebral cortex in auditory-and-speech areas. Shklovskyi (1939) named this disorder “combined auditory-and-speech lesions.” He contended that a previously unknown category of children had been discovered and “brought through from their practically deaf-mute condition.” Based on this theory, he created a distinct classification of persons with hearing disabilities that was actively promoted within the educational practice of educating children with hearing impairments and in the system of schools for children with disabilities.

Even a new type of school was created for children “brought through from their practically deaf-mute condition” (which existed for several years). Thus, deaf-mute children, children with late deafness, partial hearing loss, and other disabilities were placed in the same classrooms. This practice impeded the differentiation of schools and led to confusion among teachers and education authorities. However, the efforts to restore the differentiated system of schools for persons with hearing disabilities persisted. Eventually, the truth of Boskis’ (1959) views was officially recognized and Shklovskyi’s (1939) theory refuted as invalid. Thus, the system of special schools for children with hearing disabilities relied on the psychological and pedagogical typology of persons with hearing disabilities designed by Boskis. Policies adopted at this stage enabled a clearer definition of categories and groups of children with hearing and speech disabilities. In addition to the categories of children with hearing disabilities in Boskis’ typology, children with combined hearing and speech disabilities (combination of hearing disabilities with aphasia) were isolated in a separate group. Based on this classification, schools for children with speech disabilities served children with aphasia, stutter (when they could not attend regular schools) and other severe speech disabilities.

The final stages of introducing universal education and the further development of differentiated schooling for persons with disabilities were halted by the Second World War. This war became an immense disaster for the Ukrainian people (in 1945 the population of the Ukrainian SSR was estimated at 27.4 million people compared to 41.7 million in 1941) and inflicted grave economic damage (Petrovskyi, Radchenko, & Semenenko, 2007). Still, once Ukrainian territory was taken back, the network of special schools began its gradual renewal.

In those years, the Ministry of Education of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic obliged local departments of people’s education to complete the implementation of universal compulsory education for children with disabilities. The resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR “On measures to provide universal education for children with hearing, speech, vision and mental disorders” (1950) and other policies specified the types of schools for children with disabilities. Also, they set out a streamlined system of schools that was supposed to provide education separately to groups of students differentiated according to the nature of their disabilities and ensure the continuity of such education (these levels of schooling, i.e., primary, lower, and upper secondary, exist to this day).

After Stalin died in 1953, Ukrainian society experienced certain trends toward liberalization touching upon all aspects of Soviet society. In addition, the scientific and technical revolution that was getting underway required a transformation in the economy, hence the need for skilled workers and better qualified mid-level staff, which called for reforms in education. Yet, contrary to the liberalization process, Moscow maintained its control over practically all spheres including scientific research (in 1955 the Ukrainian Defectology Research Institute was closed down, which affected the progress of Ukrainian special pedagogy).

However, even under these circumstances steps were made (a series of orders and resolutions issued at the government and departmental levels) to improve the education system for persons with disabilities. In the 1950s, the network of schools for different categories of persons with disabilities expanded considerably; there was further differentiation; special classrooms were organized in factory apprenticeship schools; special pre-schools opened and segregated classrooms for different categories of children with disabilities were established at regular pre-schools. This growth is illustrated in Table 3 using the schools for children with visual disabilities as an example.

Similarly, positive dynamics were observed in the network of schools and pre-schools for children with hearing disabilities:

- school year 1952–1953 – 50 schools (6,231 students);

- school year 1953–1954 – 55 schools (7,328 students);

- school year 1954–1955 – 63 schools for deaf children, 2 for hard-of-hearing children (with a total of 7,155 students);

- school year 1966–1967 – 56 pre-school classrooms at 19 boarding schools (674 children), 10 schools for hard-of-hearing children (1,500 students), 35 schools for deaf children (5,600 students) (Taranchenko, 2013).

Table 3. The Network of Schools for Children with Visual Disabilities, 1955–1961.

| School Year | Total |

| Schools for blind children | |

| 1955–1956 | 14 (1,075 students) |

| 1959–1960 | 8 (894 students) |

| 1960–1961 | 8 (904 students) |

| Schools for partially sighted children | |

| 1955–1956 | 4 (355 students) |

| 1959–1960 | 6 (559 students) |

| 1960–1961 | 6 (721 students) |

In the late 1950s, special classrooms appeared at vocational schools and special schools to train students with disabilities who, on the completion of such training, went into jobs at enterprises run by the deaf society or the blind society. Steps were taken to further enlarge the vocational training system. Special vocational schools for persons with disabilities were established under the Ministry of Social Welfare and special classrooms were organized at regular vocational schools. So, it may be said that in the early 1960s the right of persons with disabilities to vocational education, special secondary education and higher education was enshrined at the legislative level and implemented in practice. The first such classroom for persons with hearing disabilities opened at the Kyiv Training School for Light Industry in 1958. A year after a similar classroom was created at the Kharkiv School of Engineering and at the School for Mechanical Wood Processing in Zhytomyr in 1960.

Advancements in Special Education Teaching and Legislative Directives (1960–1990)

The period between the 1960s and 1990s was marked by significant challenges in the development of Ukrainian special education teaching even though there were restrictions in the selection of research themes and quotas placed on degree candidates and doctoral theses. Nevertheless, this period saw advancements in special education. Ukrainian researchers and practitioners drafted a policy framework for special schools (the “Provision on special schools for children with different developmental disorders,” curricula, syllabi, etc.) to ensure sustained teaching and learning process in these settings. Basic sets of teaching and learning materials were designed (textbooks, teacher’s guides, other teaching and learning aids). During these years the majority of persons with disabilities of all age groups were covered by special school and pre-school services (Taranchenko, 2013).

The decades of 1970s–1980s witnessed continued encroachment on the national interests of Ukraine from the central authorities and increasing government centralization. The Ukrainian SSR became a large field for uncontrolled initiatives by central institutions against the background of a growing economic and social crisis. During this period, the first steps were made to draft new education legislation. In 1973 the new law “On approving the fundamental principles for the legislation if the USSR and the Union Republics regarding people’s education” (1973) laid down the basic principles and objectives for the public education system. For example, this law stipulated that special schools and boarding schools were to provide their students with appropriate education, therapy and training for socially useful work. In 1974 the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR passed the corresponding Law of the Ukrainian SSR “On People’s Education.” It envisaged creating special pre-schools for children with disabilities and specified the respective staffing and class-size policies. It also contained provisions on establishing special evening schools and correspondence schools for persons with disabilities who were employed in the national economy and special classrooms at regular schools (for working young people). In addition, in the 1970s higher education institutions resumed the practice of providing separate group instruction for persons with disabilities.

One of the most pressing problems in the 1970s–1980s (and, in fact, during the following decade) was the quality of education actually provided to most students with hearing disabilities during their 10–12 years of special school. When they graduated, at the age of 19 years as a minimum, their knowledge and skills were just at the lower secondary level. This hampered their transition to active working life. Consequently, some of them dropped out after the end of primary education. Often special school graduates had inadequate levels of general and speech development and lacked the skills to proceed to vocational training and continue their education at evening classes organized at special or regular schools or vocational schools which, in addition to vocation training, also taught the upper secondary curriculum. This created a challenge for researchers to find ways to significantly improve the attainment levels of special school students. To respond to these challenges, a number of measures were suggested that included improving school practices and creating opportunities to provide complete secondary education in the following couple of years. The proposed strategy for special schools was to continue to operate as a unique learning setting, taking into account the peculiarities of students with disabilities rather than copying the respective stages of regular school education. The transition to compulsory universal secondary education required substantial improvements in the educational content offered to students with visual disabilities, hearing disabilities, mobility problems, and speech and language disabilities (Taranchenko, 2013).

In the early 1980s, the Ukrainian SSR entered a new stage of social, political and economic development, initiated by the spread of democratic ideas in society. These trends were directly relevant to pedagogical science and the education system that, too, embarked on a new phase of development. These years were characterized by the school reform that started in practically all developed countries (which moved into post-industrial societies). The USSR also had to launch a period of reform, since the disparities in the education levels of the population and scientific advances between the Western world and the “country of full-fledged socialism” were quite obvious.

On the whole, the evolution of the special education system to serve persons with disabilities during the Soviet period may be described as complicated and quite controversial, since it was happening in a closed and authoritarian society. The growth of the special school network and the differentiation of educational services for persons with disabilities were very slow; and in fact during this period it became a closed system with some partial integration observed in vocational and tertiary education. The government policy and the economic system of the USSR based on administrative command and central planning held back the progress of Ukrainian special education, which could have worked as a catalyst and driving force for the evolution of the education system for persons with disabilities during that period.

From Totalitarianism to Inclusion: Toward Irreversible Progressive Changes in Education

The disintegration of the Soviet empire, of which Ukraine was a part up to 1991, and the fall of the totalitarian communist regime have led to a gradual value shift within the Ukrainian state. It began to reconsider its view of human rights, children’s rights, and the rights of persons with disabilities. This reconsideration laid the foundation for a new social philosophy were the Ukraine citizens accept holistic approaches to social relationships, acknowledge the rights of minorities, including the rights of persons with disabilities.

After gaining independence, Ukraine declared that it recognized the key international legal instruments regarding persons with disabilities. However, national policy is still largely compensatory in nature and mainly focuses on providing some small financial assistance and services. Until recently, making actual changes to various aspects of life to meet the needs of persons with disabilities and enable their successful integration into the community wasn’t formulated as an objective.

Both the general public and the authorities describe the state of the Ukrainian special education system that has been serving the majority of children with special needs and the prospects for its development as being in crisis. “Criticism was and is expressed regarding the social labeling of children with special needs as ‘defective’ or ‘abnormal’; the failure of the special education system to cover the total student body that require its ‘services’ (e.g., it does not reach children with profound disabilities or provide specialized psychological and educational support for children with milder disabilities); its rigidity and one-option approach to the provision of special education services; and the supremacy of the academic curriculum over the personal development of the child” (Kolupayeva, 2009). Ukrainian legislation regarding persons with disabilities formerly contained a range of legal norms. These norms: were formalized in different policy documents enacted at different times; were related to different categories of persons with disabilities; and are conflicting and inconsistent. All this created challenges for practical implementation.

Until a few years ago, in Ukraine children with various special needs were educated within the special education system. This system consists of a network of differentiated schools and other settings that operate in innovative formats (e.g., rehabilitation centers, recreation centers, social and pedagogical centers, social, medical and pedagogical centers). In Ukraine, the responsibility for special schools for children with disabilities and special needs falls under the auspices of different government ministries. Therefore, such schools are funded separately from different sources. Also, this situation created a certain degree of isolation, because these facilities operate as treatment centers where children stay for a month or as educational settings where children are placed for the entire period of their schooling. It also affects material and technical resources in these learning institutions, the provision of teaching and learning aids, and staffing. The Ministry of Education and Science is responsible for special schools and pre-schools, psychological, medical and pedagogical support centers, education and rehabilitation centers. Recreation centers, early intervention centers, and children’s homes fall within the remit of the Ministry of Health. The Ministry of Social Policy maintains children’s orphanages, social and pedagogical rehabilitation centers, and special children’s homes. The lack of integrated responsibility for settings for children with special needs poses a range of problems, because these departmental barriers hinder efforts to create a complete register of children with special needs and to establish an integrated system of social and pedagogical assistance and support.

The Ukrainian special education system is characterized by vertical and horizontal structures. The vertical structure is based on age groups and the levels of schooling accepted in regular education. The horizontal structure takes into account the psychological and physical development of a child, his/her learning needs and the nature of the disability. The vertical structure is determined by age group:

- early childhood (from 0 to 3 years);

- pre-school (from 3 to 6–7 years);

- school and vocational training (from 6–7 to 16–21 years).

During the early childhood period (0–3 years) children stay with their families, at pre-schools and orphaned children are placed in children’s homes. Children with various disabilities can access specialized services at early intervention centers, rehabilitation centers, psychological, medical and pedagogical support centers and at special pre-schools. For pre-school children with special needs there are special pre-schools, pre-schools that provide compensatory intervention services, special classrooms at regular pre-schools, pre-school classrooms at special schools, and rehabilitation centers.

The horizontal structure of the special education system in Ukraine consists of eight types of special learning settings: for children with severe hearing disabilities (including deaf children); for children with hearing disabilities; for children with severe visual disabilities (including blind children); for children with visual disabilities; for children with severe speech disabilities; for children with musculoskeletal disabilities; for children with intellectual disabilities, and for children with psychological disabilities.

The experience of Ukrainian special schools demonstrates a number of achievements within such learning settings, such as a good pool of material resources; well-established processes for providing rehabilitation interventions; vocational training, arrangements for academic learning and recreation. But alongside these undeniable positive aspects, it is important to highlight the weaknesses of the modern special education system, as described below.

- Due to its unified nature the special education system fails to meet the learning needs of all students with disabilities. It impedes the use of syllabi that could offer multiple options for teaching and learning and makes it more difficult to change or add to the existing curricula, as required.

- Being the main type of special learning settings today, special schools create an isolated environment for children with disabilities, which have multiple social implications of a negative nature, for example, alienation of families from the education and upbringing of their children; social immaturity of students; limited opportunities to acquire life skills.

- The teaching and learning process at special schools lacks social and practical aspects. As a result, students graduate with low social and economic skills; have difficulties in understanding social norms and rules; lack independent living skills, etc.

- Because of limited individualization and the lack of a student-centered approach in teaching and learning, students experience emotional and personal challenges, have an inadequate view of their own characteristics, strengths and capabilities.

- As a result of ineffective therapy and interventions students fail to develop communication skills and experience feelings of social withdrawal and isolation.

- The lack of licensed instruments for psychological and educational assessment creates difficulties in making the right decisions regarding placement and appropriate organization of teaching and learning.

- In addition, there is a gap in theoretical and methodological guidelines, teaching and learning materials that can be used with children who have severe and atypical disabilities and require additional educational, intervention and rehabilitation services.