SPECIAL EDUCATION TODAY IN SOUTH AFRICA

Sigamoney Naicker

ABSTRACT

The chapter on special education in South Africa initiates with a very comprehensive historical account of the origins of special education making reference to the inequalities linked to its colonial and racist past to a democratic society. This intriguing section ends with the most recent development in the new democracy form special needs education to inclusive education. Next, the chapter provides prevalence and incidence data followed by trends in legislation and litigation. Following these sections, detailed educational interventions are discussed in terms of policies, standards and research as well as working with families. Then information is provided on regular and special education teacher roles, expectations and training. Lastly, the chapter comprehensively discusses South Africa’s special education progress and challenges related to budgetary support, staff turnover, and a lack of prioritizing over the number of pressing education goals in the country’s provinces.

INTRODUCTION

The policy of inclusive education in South Africa, adopted in 2001 at a country level, is a radical departure from its previous special education policy. The radical changes that have taken place in South Africa after the transition from an apartheid state to a new democratic country in 1994 did not leave special education untouched. The policy process underpinned by the human rights culture impacted significantly on shifting thinking from special education towards an inclusive approach to education. Like general education, special education was one of the most unequal areas of education with resources skewed leaving the majority of the black population neglected in terms of access to schooling, teacher training and almost all aspects of schooling.

The post-apartheid dispensation, in view of a lack of a human rights culture, advanced human rights as a key component of transformation towards a non-racial society. Special Education was targeted as a very important area that required a human rights culture. The South African education system in developing White Paper Six on Special Needs Education: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System which was launched in 2001, prepared the foundation for the transformation of special education. The major plan was to rupture theories, assumptions, models, tools and practices of Special Education thus creating the conditions for Inclusive Education strongly underpinned by a human rights culture.

Similar to the other policy processes, South Africans had to contend with a number of policy interventions that were competing in a tough fiscal environment. Besides the financial constraints, there were several backlogs as a result of 350 years of colonial rule that favoured the minority population whilst the majority of black people occupied the status of either the working class or underclass. The policy intention and how it played itself out in different contexts will be some of the issues that are given consideration in this chapter.

ORIGINS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION IN SOUTH AFRICA FROM ITS COLONIAL AND RACIST PAST TO A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY

The history of South African special education provision and education support services, like all other aspects of South African life during the colonial and apartheid era was largely influenced by fiscal inequalities in terms of race (Naicker, 2005). In the light of the different and complex developments in special education and education support services in South Africa, the history of special education and education support services has been divided into historical phases(see Table 1) (Naicker, 1999, 2005).

Table 1. Different Phases and Stages in the Development of Special Education in South Africa.

| Phase |

Stage |

Characterization |

| 1 |

|

Lack of provision |

| 2 |

1 |

Provision by church and private organizations |

| |

2 |

Development of standardized tests |

| |

3 |

Development of medical model |

| 3 |

1 |

Beginning of institutional apartheid and the provision of disparate services |

| |

2 |

Racially segregated education and the development of special education services |

| |

3 |

Special education in homelands and Bantustans and the promotion and politicize of ethnic differences by the apartheid government |

| 4 |

|

Developments in the new democracy |

There are difficulties in clearly demarcating the above phases and in portraying the complexities which existed within the fragmented African section of the South African population. These complexities include: (1) the introduction of the Homelands with their own separate policies (or rather, lack therefore) which was manifested in very limited provision in, for example the Transkei, Ciskei, and Bophutswana; (2) different policies of the South Africa Department of Education and Training which is responsible for the nation’s education; (3) policies shaped by South Africa’s Bantu Education Act of 1953; (4) the fragmented nature of South Africa’s society based on racial distinction; and (5) the varying state policies with different intervention times for whites, Africans, who were divide into Homelands and locally, coloureds, and Indians. With these complexities in mind, the following section delineates the four phrases.

PHASE ONE: ABSENCE OF PROVISION (1700S–1800S)

Here, as everywhere else in the world, the South African society in the 1700s and early 1800s saw little provision for any type of special education need. Mostly, persons with disabilities were viewed by society as a sign of ‘divine displeasure’, a superstitious attitude which led to the chaining, imprisonment and killing of people later recognized as persons with intellectually impairments, physical disabilities, visual impairments, hearing impairments, and emotionally disturbance. The ‘divine displeasure’ attitude influenced to a large extent the negative treatment of people who were constructed as disabled within the South African context since it was a colonized territory.

PHASE TWO: WHITE-DOMINATED PROVISION, AND THE IMPORTANT ROLE OF THE CHURCH (FROM LATE 1800S–1963)

Stage One: Provisioning by Church, Private Organizations and Society, and the Racist Nature of the State

The title of this phase is self-explanatory and intentionally used to reflect the oppressive nature of special education policy on the part of the South Africa state during the period 1863–1963. Whilst the effect of racial practices is still being felt today, long after 1963, this particular phase began to set the pattern for later years and was most striking in terms of racial disparities. These disparities become evident when one looks at the chronology of special education provisions. For example, no special education provision was made by the South Africa state for African children. In fact, it took a century for the state to provide subsidies for African persons with hearing impairments, visual impairments, and physical disabilities. These subsidies occurred in 1963.

The church played an important role during this phase. It initiated the first provision of special education for children with disabilities for both white and ‘non-white’ children, through the Dominican Grimley School for the Deaf in 1863. In 1863, Dr Grimley, Vicar Apostolic of the Cape of Good Hope, who had been actively associated with the education of the deaf in Dublin, invited the Irish Dominican sisters to work in South Africa. The superior of the pioneer group of sisters, Mother Dympna, began to teach some deaf children on her arrival at the Cape and shortly afterwards the Grimley Institute (now known as Dominican Grimley School) was founded under the patronage of the Vicar Apostolic.

More importantly, the church continued to provide a service to ‘non-white’ children in the absence of state provision for these children for the next century. The church’s special education provision was an important factor in South Africa’s recognition of the existence of white church-run schools in 1900 which lead to the state’s promulgation of the White Education Act 29 in 1928. This Act, allowed the State Education Department to establish vocational schools and special schools for ‘white’ children with disabilities.

The White Education Act 29 of 1928 provides the first signal of the model of special education in South Africa. Although it mainly concerned white learners, it provided the foundation for South Africa’s Special Education Act of 1948. This Act made provision for separate special schools for several categories of disability which include the: deaf, hard of hearing, blind, partially sighted, epileptic, cerebral palsy and physically disabled. Act 29 worked on the assumption that learners were deficient and that their deficiencies were pathological, a perspective that was strongly influenced by the medical thinking of professionals at that time. Unfortunately, this pathological perspective associated disability with impairment and loss and it did not take systemic deficiencies into consideration.

The state increasingly favoured white students with special needs and in 1937 passed the Special Schools Amendment Act which created the first provision for hostels in special schools for whites. The provision of hostels meant that provision was made for learners to live in the schools they attended. Positively, the church and other private associations and societies continued to provide support for ‘non-white’ children. For example, they were responsible for establishing (1) the Athlone School for the Blind for coloured children, (2) a school for blind Indian children and (3) the Worcester School for coloured children with epilepsy. South Africa has a fairly long history with regards to the education of learners with disabilities. It started 1863 when the Roman Catholic Church established the first school for deaf children in Cape Town.

From the initiatives taken by the Catholic and other churches, the service gradually grew to the current 20 schools for blind, 47 for deaf, 54 for physically disabled and cerebral palsied, 2 for autistic and quite a number for intellectually disabled learners. The establishment of schools for disabled learners was mainly due to private initiative (churches, other private organizations and individuals) and for specific disability groups.

Stage Two: Development of Tests as a Precursor to Institutional Special Education and Education Support Services

The 1920s saw the first development of intelligence tests in South Africa. Professor Eybers, of the then University College of Orange Free State, published an individual intelligence scale called the Grey Revision of the Stanford-Binet Scale (Behr, 1980, 1984). The development of tests to evaluate students with special education needs continued in white education and their usage in schools increased. For instance, in 1924, a committee, appointed by the Research Grants Board of the Union Department of Mines and Industries and under the chairmanship of Professor R. W. Wilcocks, designed a test, which came to be known as the South African Group Test of Intelligence. This marked the first connection between education and the labour market in South Africa and was the precursor to aptitude tests. Later, in 1926, Professor J. Coetzee of Potchefstroom University published the first standardized arithmetic test in South Africa for whites. In 1929, both the Wilcocks and Coetzee tests were used in the Carnegie Poor White Survey and later in the Bilingualism Survey (Behr, 1980). The Poor White Survey was commissioned to establish ways in which the poor whites could be uplifted. There was a fear that that poor whites and poor blacks will socialize which could lead to a multi-racial society.

In 1939, Dr. Fick developed the individual Scale of General Intelligence for South African Schools. This scale was used in schools to assess the cognitive capacity of students with disabilities until the mid-60s. The scale was the precursor of categorization and labelling of students with intellectual and learning disabilities. Unfortunately, since IQ tests were later used not only for whites, but also for all children to assess intelligence in children and place them in special education programmes, it perpetuated the ‘exclusive’ education philosophy in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In addition, these tests became a highly valued component to psychological services in schools (currently associated with education support services), a basis for adaptation classes (in Coloured Education), adjustment classes (in Indian Education) and remedial education.

Stage Three: The Genesis of the Medical Model

The 1948 Special Schools Act in white education introduced into special education a model that incorporated a medical and mental diagnosis and treatment. This model focused on the individual deficit theory and viewed the person as a helpless being. The model was firmly entrenched in the charity and lay discourses (Fulcher, 1989). The medical discourse shaped and largely influenced ‘exclusive’ special education practices in the field which continued for decades after its introduction in South Africa’s education system due to its highly convincing theme which, according to Fulcher (1989):

Suggests, through its correspondence theory of meaning, that disability is an observable or intrinsic, objective attribute or characteristic of a person, rather than a social construct. Through the notion that impairment means loss, and the assumption that impairment or loss underlies disability, medical discourse on disability has deficit individualistic connotations. Further, through its presumed scientific status and neutrality, it depoliticizes disability; disability is seen as a technical issue, (and) thus beyond the exercise of power. Medical discourse individualizes disability, in the sense that it suggests individuals have diseases or problems or incapacities as attributes. (p. 28)

Thus, disability was associated with an impairment or loss. The entire focus was on the individual who was viewed as helpless and dependent. The individual deficit theory viewed the person as in need of treatment and assistance outside regular education. No attempt was made to establish the deficiencies of the system; for example, a person with physical disability using a wheelchair required a ramp to gain access to a mainstream school, which was not provided for by the system. Access to education was prevented as a result of barriers, which reflect a deficient system and not a deficient person.

This medical discourse model was also the beginning of the professionalization, and consequently the mystification, of special education in South Africa for regular education teachers. Fulcher (1989) is appropriate here in her comments about the medical discourse:

it professionalizes disability: the notion of medical expertise allows the claims that this (technical) and personal trouble is a matter for professional judgment. (p. 28)

Following this prevailing belief, regular education teachers were led to believe that it was beyond their level of expertise to teach learners who were classed as disabled and these students must be educated by specialists. Unfortunately, such beliefs perpetuated the idea that students with disabilities must be excluded from regular education thus making inclusive education not possible. This idea, according to Fulcher’s (1989), led to the proliferation of educational psychology and related disciplines practice, namely, a

medical discourse, through its language of body, patient, help, need, cure, rehabilitation, and its politics that the doctor knows best, excludes a consumer discourse or language of rights, wants and integration in mainstream social practices. (p. 28)

Therefore, the depoliticizing, individualizing and professionalizing of disabilities led to the notion that learners who were viewed as disabled had to be taught in special schools and/or classes, while their rights were ignored. Parents of learners were intimidated by the knowledge of professionals and therefore did not challenge the decisions concerning placement.

PHASE THREE: ‘SEPARATE DEVELOPMENT’ AND ITS IMPACT ON SPECIAL EDUCATION AND EDUCATION SUPPORT SERVICES (1963–1994)

Stage One: Institutional Apartheid and Disparate Service Provision for the Four Race Groups

The year 1948 ushered in the introduction of institutional apartheid into every facet of South African life. The National Party’s policy of separate development ensured apartheid by dividing students into four groups, namely, ‘Africans’, ‘coloureds’, ‘Indians’ and ‘whites’. This had significant implications for special education and education support services. Whilst the concept of education support services (known traditionally as psychological services, or auxiliary services) evolved only at a much later stage (1992) in South African education, it must be noted that the initial precursor was the introduction of the psychological services that were initiated after the above introduction of separate development. The School Psychological and Guidance Services of South Africa’s Department of Education in the Transvaal, after the promulgation of Act No. 39 of 1967 for ‘whites’, saw, the clinics established and staffed by clinical psychologists, vocational guidance psychologists, orthodidacticians, speech therapists, sociopedagogic psychologists and occupational therapists (Behr, 1980). These clinics which were staffed by multi-disciplinary professionals proved to be a workable model and paved the way for special education support services several decades later (National Education Policy Investigation, 1992).

Stage Two: Segregated Education Departments Take Control of Special Education and Education Support Services Provision

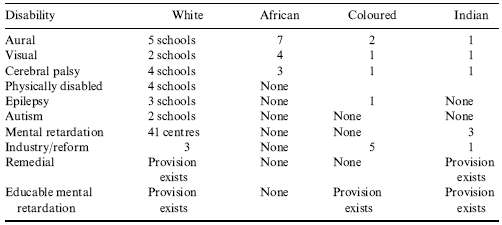

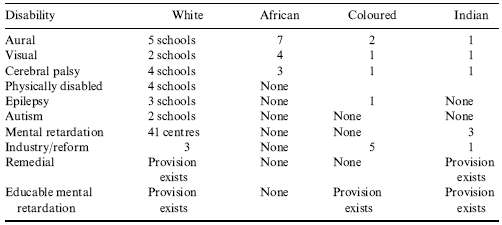

Education, as one of the pillars of separate development, was used as an instrument to ensure that all four groups accepted the idea of that policy. The passing of the Coloured Persons Education, Bantu Education and Indian Education Acts, in 1963, 1964 and 1965 respectively, saw special education and education support services being taken over by the various departments. Unfortunately, the disparities in special education and education support provision were clearly racial and became very visible with the unfolding of separate development. Table 2 illustrates these disparities (Behr, 1980).

Table 2. Provision and Schools for the Different Types of Disability.

Source: Behr (1980).

Behr (1980) reported that ‘Whites’ made up 17.5%, ‘Africans’ 70.2%, ‘Coloureds’ 9.4% and ‘Indians’ 2.9% of the population. Table 2 shows clearly that special education provision favoured ‘whites’. The provision problem with regard to bias towards ‘whites’ was actually worse than it appeared since churches and private associations and societies had initiated the development of ‘non-white’ special schools while special education for whites had been provided mainly by the State.

In psychological services (a precursor of today’s special education support services) there were major discrepancies on racial lines. For example, in the Transvaal, under the wing of the School Psychological and Guidance Services, an elaborate system of child guidance clinics was established for each of the 24 inspection circuits. In this system, a clinic served a group of schools. A multi-disciplinary team carried out intellectual, scholastic, and emotional assessments of pupils, and provided help in the form of psychotherapy, pelotherapy and speech therapy. In addition, clinics were concerned with identifying and guiding children with learning deficits, cultural deprivation and behavioural problems. Other provinces had similar services, but not as elaborate as the Transvaal’s (Behr, 1980).

While the Department of Bantu Education did establish a section with psychological services, it was restricted to assessing all pupils in Form I and Form III (Form 1 is grade 6 and Form III is Grade 10) to help teachers and lecturers assess their teaching. Also, psychological services for coloureds were instituted and at least one teacher in each school was concerned with guidance. In addition, training was provided for secondary teachers who had taken psychology as part of degree course responsible for guidance. School Psychological Services in Indian Education focused mainly on assessing and placing pupils needing special education (Behr, 1980).

Except for Indian Education, which had several psychologists, an inspector of psychological services and a school guidance office, there was little comparison between the resources of white education and other race groups. This disparity resulted in poor supervision of adaptation classes, remedial education and facilities at special schools where they existed.

Stage Three: The Homeland or Bantustan Phase

In 1968, the South Africa state conferred Territorial Authorities to six ‘Homeland’ government departments, with each having a separate education department. However, this did not result in any significant changes for African children with special education needs. Furthermore, there was little information on the actual development of special education and education support services in these territories (National Education Policy Investigation, 1992). However, it followed the pattern and trends of the ‘separate development’ phase relating to the number of pupils in special schools as a ratio of total enrolment for the various races: Indians 1:42; whites 1:62; coloureds 1:128; and Africans 1:830 (National Education Policy Investigation, 1992).

PHASE FOUR: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE NEW DEMOCRACY; FROM SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION TO INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

As mentioned earlier, the advent of the democratic government in 1994 saw wide-scale transformation taking hold throughout the country in many aspects including education. This included the unification of 19 education departments into a single Ministry of Education. The unification was tantamount to a revolution. The disparities and lack of provision for mainly black South Africans clearly reflected the need to conduct intensive research with a view to providing educational service that could benefit all South Africans. It was against this background that the democratic government appointed the National Commission on Special Education Needs and Training (NCSNET), as well as the National Committee on Education Support Services (NCESS), in 1996. While the NCSNET and NCESS were established as separate entities by the Ministry of Education, the two agencies decided to work jointly as a single group in the light of overlapping functions. This was clearly spelt out in the Department of Education (1997) single report of the NCSNET and NCESS:

In the early stages of the work of the NCSNET and NCESS, it became evident that the links between these areas were so close that they required a joint investigation. The first meeting of both bodies was held in mid-November 1996. The NCSNET and NCESS initially commenced their investigations within separate task groups. By the third meeting in January 1997, it was evident that the investigations overlapped in so many ways that it was necessary to amalgamate and conduct both consultative and research work through joint structures and processes. (p. 10)

The work of NCSNET and NCESS lasted for a year (1996–1997), during which these bodies consulted widely with key stakeholders in education. Workshops and public hearings were held in all provinces, since consultation with all interested parties formed part of the terms of reference of the NCSNET and NCESS and was regarded as crucial.

The terms of reference adopted by NCSNET and NCESS had to heed the major proclamations and other policy documents during the period of transformation. For example, the new Constitution of the Republic of South Africa had this to say: ‘Every person shall have the right to basic education and equal access to educational institutions’ (p. 16). The Department of Education’s (1996) White Paper on Education and Training was also clear on the question of rights:

It is essential to increase awareness of the importance of ESS (Education Support Services) in an education and training system which is committed to equal access, non-discrimination, and redress, and which needs to target those sections of the learning population which have been most neglected or are most vulnerable. (p. 16)

Further, the White Paper on an Integrated National Disability Strategy, produced by the Disability Desk of the Office of the Deputy State President (1997), offered very clear direction to the NCSNET and NCESS:

An understanding of disability as a human rights and development issue leads to a recognition and acknowledgement that people with disabilities are equal citizens and should therefore enjoy equal rights and responsibilities. A human rights and development approach to disability focuses on the removal of barriers to equal participation and the elimination of discrimination based on disability. (p. 10)

In November 1997, in the Department of Education report titled, ‘Quality education for all: Overcoming barriers to learning’, the NCSNET and NCESS recognized the need for all learners to gain access to a single education system and thus be able to participate in everyday mainstream economic and social life. The recommendations of the NCSNET and NCESS were largely phrased in the language of human rights, which differed radically from that of the medical discourse perspective as it moved away from individualizing, professionalizing and depoliticizing disability by stating that:

… Barriers can be located within the learner, within the centre of learning, within the education system and within the broader social, economic and political context. These barriers manifest themselves in different ways and only become obvious when learning breakdown occurs, when learners ‘drop out’ of the system or when the excluded become visible. Sometimes it is possible to identify permanent barriers in the learner or system, which can be addressed through enabling mechanisms and processes.

However, barriers may also arise during the learning process and are seen as transitory in nature. These may require different interventions or strategies to prevent them from causing learning breakdown or excluding learners from the system. The key to preventing barriers from occurring is the effective monitoring and meeting of the different needs among the learner population and within the system as a whole. (Department of Education, 1997, p. 14)

By identifying the education system and individuals with disabilities as reflecting or experiencing potential barriers to learning, the NCSNET and NCESS had moved away from viewing disability as only an individual loss or impairment. Furthermore, NCSNET and NCESS suggested that these barriers could be addressed in a regular school and that regular education teachers needed to be trained to identify and deal with barriers to learning and development. These barriers could include the following: socio-economic factors, attitudes, inflexible curriculum, language and curriculum, inaccessible and unsafe built environments, inadequate support services, lack of enabling and protective legislation and policy, lack of parental recognition and involvement, disability (learning needs not met) and lack of human resource development strategies. In their recommendations, and as part of the principles on which their work was based, the NCSNET and NCESS called for ‘equal access to a single, inclusive education system’ in which:

Appropriate and effective education must be organised in such a way that all learners have access to a single education system that is responsive to diversity. No learners should be prevented from participating in this system, regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, language, or other differences. (Department of Education, 1997, p. 66)

An educational development that preceded the work of the NCSNET and NCESS was the introduction of a general curriculum, namely, the Outcomes-Based Education (OBE). The NCSNET and NCESS recommended that a single education curriculum and urged that diverse special education needs be firmly incorporated within the OBE that had already been under way in South Africa. This NCSNET and NCESS argued that OBE had the capacity to deal with diversity as a result of its flexibility and its premise that ‘all students can learn and succeed, but not on the same day in the same way’ (Spady, 1994, p. 9).

EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTIONS (POLICY, STANDARDS, RESEARCH)

Education White Paper Six on Special Needs Education: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System (Department of Education, 2001) suggests a 20-year plan to transform the system from a dual to a single system of education. The 20 years include short-term, medium-term and long-steps. It must be noted that the previous dispensation also neglected rural education. White Paper Six has both an urban and rural focus. With White Paper 6, the government’s short-term intent was to:

- Implement a national advocacy and education programme on inclusive education.

- Plan and implement a targeted outreach programme, beginning in Government’s rural and urban nodes, to mobilise out-of-school children and youth with disabilities.

- Complete the audit of special schools and implement a programme to improve efficiency and quality.

- Designate, plan and implement the conversion of 30 special schools into resource centres in 30 districts.

- Designate, plan and implement the conversion of thirty primary schools to full-service schools in the same 30 districts above.

- Within all other public education institutions, on a progressive basis, the general orientation and introduction of the inclusion model to management, governing bodies and professional staff.

- Within primary schooling, on a progressive basis, the establishment of systems and procedures for the early identification and addressing of barriers to learning in the Foundation Phase (Grades R-3). (Department of Education, 2001, p. 42)

Therefore, White Paper Six introduced a three tier inclusive education system which includes Full-Service Schools, District-Based Support Teams and Special Schools as Resource Centres. These three systems are described below.

Full-service/inclusive Schools, further and higher education institutions are first and foremost mainstream education institutions that provide quality education to all learners by supplying the full range of learning needs in an equitable manner (Department of Education, 2010). A full-service school would be equipped and supported to provide for a greater range of learning needs. As learning needs and barriers to learning arise within a specific context and vary from time to time, it is obvious that full-service schools should be supported to develop their capacity and potential for addressing and reducing barriers to learning, as well as seeing their educational provision in a flexible manner. Following this thinking, a full-service school may, but not necessarily need to have all possible imaginable support to learners in place but it would have the potential and capacity to act in such a way that a support needed for a learner could be provided.

The guidelines for District-based Support Teams refer to integrated professional support services at the district level. Support providers employed by the Department of Education will draw on the expertise from local education institutions and various community resources. Their key function is to assist education institutions (including early childhood centres, schools, further education colleges and adult learning centres) to identify and address barriers to learning and promote effective teaching and learning. This includes both classroom and organizational support, providing specialized learner and educator support, as well as curricular and institutional development (including management and governance), and administrative support (Department of Education, 2005).

It is believed that the key to reducing barriers to learning within all education and training lies in a strengthened education support service. This strengthened education support service will have, at its centre, new district-based support teams that will comprise staff from provincial, district, regional and head offices and from special schools. The primary function of these district-based support teams will be to evaluate programmes, diagnose their effectiveness and suggest modifications. Through supporting teaching, learning and management, they will build the capacity of schools, early childhood and adult basic education and training centres, colleges and higher education institutions to recognize and address severe learning difficulties and to accommodate a range of learning needs.

Special Schools as Resource Centres imply the qualitative improvement of special schools for the learners that they serve and their phased conversion to special school resource centres that provide professional support to neighbouring schools and are integrated into district-based support teams (Department of Education, 2007). According to the White Paper Six, in an inclusive education and training system a wider spread of educational services will be provided according to the learners’ needs. The priorities and goals of special schools will include orientation to new roles within the district support teams which include support to neighbouring schools and full-service schools. The new approach should focus on problem solving skills and the development of learners’ strengths and competencies rather than focusing on their shortcomings and disabilities only. The special school as resource centre should be integrated into the district support team to provide support to full-service schools and ordinary schools in that district. The District Support Team should be the overseer of support required by learners within the district.

The intention here is to ensure that there is sufficient human resource development so that teachers are well equipped to deal with diversity. Further, through physical resource/material resource development, schools will be made accessible. District Support Teams, which comprise curriculum specialists, psychologists, early childhood education specialists and related personnel, will also undergo training in the area of inclusive education. The purpose of identifying a relatively small number of schools is to ensure that there is rigorous development and research that is able to establish the strengths and weaknesses of the plan. Ultimately, Full-Service schools (ordinary primary school) will be converted into a school, which caters for difference. Special Schools within this plan should have more of an outreach role to assist and support, together with the District Support Team, the Full-Service School and the Ordinary School. Advocacy focusing on inclusive education will be conducted within the 30 districts, as well as system-wide, to ensure that there are sufficient common understandings about government’s plans. It is envisaged that this process will lead to the following outcomes:

• Costing of an ideal district support team.

• Cost of conversion of special schools to special schools/resource centres.

• Costing of an ideal full-service school.

• Costing of a ‘full service’ technical college.

• Determining the minimum levels of provision for learners with special needs for all higher education institutions.

• Devising a personnel plan.

• Costing non-personnel expenditure requirements. (Department of Education, 2001, p. 44)

According to White Paper Six, the completion of the short-term steps should take three years. Once the research has been completed and the findings known, the medium steps should involve more schools, further education and training and higher education institutions, depending on available resources.

The notion of inclusive education, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, is shaped directly by the recommendations of the NCSNET and NCESS. Therefore, the focus is not merely on disability but rather on all vulnerable children, including over-age learners, children in prison, learners who experience language barriers, or barriers such as the attitudes of others, lack of parental recognition and poverty. The transformational goals mentioned at the beginning of this chapter becomes very relevant to inclusive education where the emphasis is on creating access and skewing funding so that it is pro poor.

What emerges clearly from the government’s inclusive education intention is that the system is being geared towards creating possibilities for the first time in the history of South Africa, pedagogy of possibility, not only in terms of race but ability, interest, intelligence and styles. Whilst the intentions are very clear, several challenges face policy implementers within the South African context.

Learners will follow programmes and receive support based on the level of support they require. The Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support strategy specifically aims to identify (1) the barriers to learning experienced, (2) the support needs that arise from barriers experienced and (3) the support programme that needs to be in place to address the impact of the barrier on the learning process.

The nature of support programmes that will be addressed within the SIAS strategy covers the following areas:

- Vision;

- Hearing;

- Mobility;

- Communication;

- Learning/Cognition;

- Health (including Mental Health);

- Behaviour and social skills;

- Multiple and Complex Learning Support.

The provisioning drivers for the support programmes are:

(1) curriculum and assessment adjustments;

(2) training requirements;

(3) availability of specialized staff;

(4) specialized LTSM /assistive devices and other resources to ensure access to education.

The strategy rates the level of the identified support that is required as a low, moderate or high level of provision. The organizers that guide this rating process include the frequency, scope, availability and cost of the additional support service, programme or specialized learning and teaching support material. The support provisions that are rated low cover all the support provisions in all departmental programme policies, line budgets and norms and standards for public schools. Support provisions that are rated moderate cover support provisions that are over and above provisions covered by programme policies, line budgets and norms and standards for public schools. Such provisions are provided once-off or for a short-term period or on a loan system. Implementation of such provisions can generally be accommodated within the school or regular classroom. Support provisions that are rated high are over and above provisions covered by programme policies, line budgets and norms and standards for public schools support. These provisions are specialized, requiring specialist classroom/school organization, facilities and personnel. A resource package and guidelines concerning the use of technology is currently being developed by the Department of Basic Education.

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENT ASPECTS

The issue of prevalence and incidence has always been a controversial issue in South Africa. For example, the 2010 national household survey estimates that 6.3% of people older than five years in South Africa have some form of disability. This might be an underestimation as the World Health Organization’s 2011 World Report on Disability placed the global disability population at about 15%. Therefore, there is little consensus on issues of prevalence and incidence. However, when the Department of Education’s White Paper Six was developed, disability in the schooling system utilized the World Health Organization data. It was estimated between 2.2% and 2.6% of learners in any school system could be identified as disabled or impaired. This meant that about 400,000 of South African children had disabilities or impairments. When White Paper Six was written only 64,200 children were accommodated by the schooling system. Since then, considerable progress with regards to building of special schools has been achieved.

The data collected in Census 2001 indicates that there were 2,255,982 people with various forms of disability. This number constituted 5% of the total population enumerated in this census. Of this number, 1,854,376 were African, 168,678 were coloured, 41,235 were Indian/Asian, and 191,693 were white. The number of females affected was 1,173,939, compared to 1,082,043 males.

The provincial prevalence levels show that the most affected province was Free State with a prevalence of 6.8% and the least affected province was Gauteng (3.8%). The prevalence increased by age from 2% in the age group 0–9 years to 27% in the age group 80 years and above. Those who had post-secondary education had the lowest prevalence (3%) compared to those who had no schooling (10.5%). Lastly those with primary level and secondary level of education had prevalence of 5.2% and 3.9%, respectively.

The prevalence of sight disability was the highest (32%) followed by physical disability (30%), hearing (20%), emotional disability (16%), intellectual disability (12%) and communication disability (7%). A comparison of the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of disabled and non-disabled persons shows that disabled persons were on average older. About 30% of disabled people had no education while only 13% of the non-disabled population fell in this category. However, the most affected population group in this regard were African (Census, Government of South Africa, 2001, p. 2).

TRENDS IN LEGISLATION AND LITIGATION

At this time, national legislation concerning entry and exit to special schools do not exist. The countries nine provinces accept children at the age of 3 years and the exit age is 21 years. Provinces will have to indicate what provision is made once children leave at the age of 21 years.

In revising policies, legislation and frameworks, the Ministry of Education promised in White Paper Six to give particular, but not exclusive, attention to those that relate to the school and college systems. Policies, legislation and frameworks for the school and college systems were required to provide the basis for overcoming the causes and effects of barriers to learning. Specifically, White Paper Six promised admission policies will be revised so that learners who can be accommodated outside of special schools and specialized settings can be schooled within designated full-service or other schools and settings (Department of Education, 2001).

At this time, there are no national laws concerning placement of learners with regard to age and related matters. The government indicates that provincial authorities should create placement options based on broad guidelines. Regarding admission, the South African Schools Act (Act 79 of 1996) through section 5 makes provision for all schools to be full-service schools by stating that: public schools must admit learners and serve their educational requirements without unfairly discriminating in any way; governing bodies of a public school may not administer any test related to the admission of a learner to a public school; and in determining the placement of a learner with special education needs, the Head of Department and principal must take into account the rights and wishes of the parents and of such learner while taking into account what will be in the best interest of the learner in any decision-making process (Department of Education, 2010).

The government specifies that The Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS) Strategy (SIAS) should be used to maximize learners’ participation in schools and classrooms. The aim of introducing the SIAS strategy in the education system is to overhaul the process of identifying, assessing and providing programmes for all learners requiring additional support so as to enhance participation and inclusion. One of the key objectives of the strategy is to provide clear guidelines on enroling learners in special schools and settings which also acknowledge the central role played by parents and educators. In essence these guidelines provide a strategic policy framework for screening, identifying, assessing and supporting all learners who experience barriers to learning and development within the education system, including those who are currently enroled in special schools.

Reasonable accommodation of individuals’ requirements should be made. This can in turn be realized by making provision for individualized support measures that could include facilitating the learning of Braille, using alternative script, communicating through augmentative and alternative modes, means and formats of communication, the introduction of orientation and mobility skills, and facilitating peer support and mentoring, facilitating the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the Deaf community (Department of Education, 2010).

Until now only two major cases were disputing the service provision regarding learners who are disabled. The first one involved a claim against the state regarding South African Sign Language (SASL). A learner claimed that by not offering SASL as a school subject, the Department of Education is acting in contradiction to the constitution of the country. A matric Grade 12 student, Kyle Springate, took the Department of Education to court in his quest to have sign language recognized as an exam subject. Springate discovered in 2009 that, despite having taken sign language as a subject throughout high school, sign language would not form part of his matric exam. He appealed for sign language to be recognized as an additional language, believing that it formed part of the school curriculum. Springate discovered that sign language was not a recognized subject, which meant that he faced losing points in his university application. This student ended up taking dramatic art as an extra subject and had to study three years of work for his final school year at Westville Boys’ High School in Durban. Kyle’s mother, Paige McLennan-Smith, said that this turn of events had placed her son at a disadvantage. Kyle’s mother argued that her son was exhausted after a normal day at school ‘as a result of lip-reading’, which required him to concentrate all the time during the school day. With the burden of taking dramatic arts as a subject, he was even more exhausted after a day at school. Paige argued that ‘If Kyle fails dramatic arts and his application to the university is assessed on the basis of only six subjects, he stands little chance of being accepted’. Springate hoped to study fine art at Rhodes University.

In the court papers filed at the KwaZulu-Natal High Court in Pietermaritzburg, the Department of Basic Education said that there had not yet been any consensus among organizations representing the deaf about the exact definition or components of sign language, and that this had resulted in a delay in the process of formally recognizing sign language as a subject. The court requested that the Department of Education offer sign language as a subject in view of the challenges posed to learners. Since this court case, the Department of Education has taken steps to introduce SASL as a subject (Legal Resources Centre, 2009).

The second court case (High Court of South Africa, 2010, Case No: 18678/2007-Western Cape Forum for Intellectual Disability vs. Government of the Republic of South Africa) involved a right to education of children with severe intellectual disability. In November 2010, the Western Cape Forum for intellectual disability challenged the state in the high court with concerns for the rights of the children with profound and severe cognitive deficits. They argued that the: (i) the state establishes and funds schools which include schools known as ‘special schools’ which cater for the needs of children who are classified as having moderate to mild intellectual disabilities (IQ levels of 30–70); (ii) children with an IQ of under 35 are considered to be severely (IQ levels of 20–35) or profoundly (IQ levels of less than 20) intellectually disabled and as such children are not admitted to special schools or to any other state schools; and (iii) the state makes no provision for the education of children with severe or profound intellectual disabilities (the affected children) nor does It also does it provide schools in the Western Cape for such children.

The High Court decided that the State has failed to take reasonable measures to make provision for the educational needs of children with severe and profound intellectually disabilities children in the Western Cape, thus being in breach of the rights of those children to basic education, protection from neglect or degradation, equality and, human dignity. The State was instructed to take reasonable steps and interim measures in order to address the above challenges experienced by the children.

WORKING WITH FAMILIES

South African parents, teachers and learners are important partners in attempting to improve performance of learners. However, the social portrait even in the second richest province, namely, Western Cape, suggests that many parents do not have the requisite levels of education. Quite clearly there is a relationship between parent’s education and their commitment to socializing children into education. This of course is a universal experience. Departments of Education have played a role in advocacy regarding the involvement of parents by maintaining close links with a number of parent organizations. Parent organizations as well as school governing body organizations have also been involved in the development of policy regarding White Paper Six. Regular meetings have been held between the Department of Education and school governing bodies and parent organizations at both the national and provincial level. These organization include, Disabled Children’s Action Group (DICAG) South Africa, Downs Syndrome Association of South Africa, South African National Organization for the Deaf, Special Education Parent Teacher Organization, Disabled People South Africa (DPSA) and, South African National School Governing Body Association.

Of all the above-mentioned groups, DICAG was one of the most powerful and influential. Their representatives sat on almost all major transformation committees when White Paper Six was developed. DICAG was established in 1993 by the parents of children with disabilities. Their main aim is to empower themselves to educate children in an inclusive environment to ensure equal opportunities for children with disabilities.

DICAG was initially affiliated to Disabled People South Africa (DPSA), the national disabled people’s umbrella organization before it became an independent organization. It has 311 support centres, 15,000 parent members and 10,000 children actively involved. DICAG has served as a campaigning organization to help raise the level of awareness of disability as well as challenge stereotypes and perceptions of people with disabilities in South Africa.

The issue of cultural capital and education is an issue that favours middle-class families that are in the minority in South Africa. Working class families do not have the cultural capital and therefore are unable to empower their children. Many working class parents do not attach value to education since education has not helped them. They do not see the value in education based on their experiences.

In South Africa, there are many non-governmental organizations that worked with families during the apartheid era. Many of these organizations that survived financially are helping parents and families. In the disability sector, there are many parent empowerment groupings that rely on one another for support. Typically, these groups consist of parents who have children who have a particular category of disability, for example, the Downs Syndrome Organization, which comprises parents of Downs Syndrome Children. Other disability categories of children have similar organizations. These organizations are composed of mainly middle-class parents who fell into the white race group. With the transitions towards inclusive education, many black parents have joined these groupings. This is the most dominant grouping of family support but the existence of these grouping in working class areas is minimal. Positively, more and more parents are joining these organizations from different classes and races across the country with the movement towards inclusive education in South Africa. Many of these organizations continue to play a very important role in schools and various communities through outreach programmes, conferences and other forums. They are an indispensable part of the South African special education scenario with many parents playing particularly active roles. A good example is the role of the Western Cape Inclusive Education Forum. They established a resource centre and other forms of support. Many of these parents have worked in townships and have been extremely helpful to disadvantaged black children. One of the pioneers in this movement was Michelle Belknapp.

An example of a more formal organization is the South African National Council for the Blind. Traditionally, this organization has served mainly white learners but with the transition to a democracy, they serve all children. This movement towards serving all children has been adopted by most other categorical disability organizations.

In more privileged areas, there is a close relationship between the school governing body which includes parents and representatives of the school. Children who attend middle-class schools have a formal network in terms of the school governing body that establishes goals for students with their parents input at individual schools. Whilst this does not happen at a systemic level, more progress is being in underprivileged areas. Schools increasingly are required to take children from all backgrounds and parents receive support from schools where the goals of their children are discussed. For example, at the De La Bat School in the Western Cape, parents of 3-year-old children are being involved in the school’s Sign Language programmes. Parents at De La Bat School are made aware of the possibilities for their child’ learning and teaching. School personnel report that the parents play a constructive role in the lives of their children and get exposed to Sign Language once their children are admitted in school. Hopefully over the next decade, South African special school administrators will make a major systemic effort to replicate the successful parental involvement example from De La Bat School.

There are no formal transitional living and vocational training programmes that are provided in South Africa schools. However, many parents of children with disabilities get involved in this area. For example, national organizations such as the Downs Syndrome Association create awareness and opportunities for children to obtain employment. While such organizations can be helpful in this area, much work has to be done in the public schools.

TEACHERS AND SPECIAL EDUCATION (ROLES, EXPECTATIONS, TRAINING)

Teacher training requirements in South Africa require teachers to hold a 4-year teaching degree or a 3-year degree and a higher education teaching diploma. Special Education/Inclusive Education is part of the teacher training packages. Specialist training in areas of disability is lacking in South Africa with very few specialized training programmes on offer. Universities are currently working with the Department of Basic Education working on these programmes.

Teaching practice at schools is mandatory at universities and each student has to complete teaching practice for a specific period of time. This is normally a six-week period. At this time there, is a huge teaching shortage in South Africa regarding various categories of disabilities. However, this shortage in particular areas was acknowledged by White Paper Six. This also includes South African Sign Language (SASL) teachers and teachers of the visually impaired. Steps have been taken to ameliorate the challenge but it will take a significant period of time to address the backlogs. In view of White Paper Six and related White Papers, the government is playing a major role in creating the conditions for quality teacher education. Bursaries are provided for all teachers provided they commit themselves to teaching for a period of time. The bursaries are generous and cover the four-year study programme.

When White Paper Six was developed, it was envisaged that teacher education should be a priority. White Paper Six articulated the vision that classroom educators will be the primary resource for achieving the goal of an inclusive education and training system. The main thrust of the plan was to ensure that educators will need to improve their skills and knowledge, and develop new ones. Staff development at the school and district level was regarded as critical to putting in place successful integrated educational practices. White Paper Six had the following foci:

- In mainstream education, priorities will include multi-level classroom instruction so that educators can prepare main lessons with variations that are responsive to individual learner needs; co-operative learning; curriculum enrichment; and dealing with learners with behavioural problems.

- In special schools/resource centres, priorities will include orientation to new roles within district support services of support to neighbourhood schools, and new approaches that focus on problem solving and the development of learners’ strengths and competencies rather than focusing on their shortcomings only.

Along with the above foci, the Ministry of Education has been training teachers within the framework of the OBE curriculum. Also, there has been an emphasis on diversity by the Department of Education. For example, in his forward to the teacher’s curriculum guide, South Africa’s Director-General of Education, Mr. Thami Mseleku, has clearly expressed a focus on diversity. In the curriculum guide, he states ‘These guidelines are geared to assist teachers in accommodating Learning Outcomes and Assessment Standards that are prescribed, yet create space and possibilities for the use of judgments and insights based on particular contexts and a diverse learning population’ (Department of Education, 2003). This curriculum document further states:

The guidelines are intended to be implemented in conjunction with other policies, for example, the White Paper Six: Special Needs Education: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System needs to be read to provide background information on issues related to barriers to learning, as these have crucial impact of what happens in the classroom. (Department of Education, 2003, p. 1)

Positively, inclusive education has been on the teacher education agenda in most of the teacher training forums across the country for the last 10 years. A dedicated section on inclusion has been a key feature in all training and orientation session relating to the South African school curriculum.

Government provides support for teachers and at this time in view of the Year of Inclusion links are being fostered with South Africa’s major universities to train prospective teachers in specific disabilities. For example, an agreement has been concluded with South Africa’s largest university, University of South Africa, for teachers to be trained to teach the visually impaired. South African Sign Language and other areas are being looked at. During the apartheid era, many teachers who taught in black schools did not have specialist qualifications in specific disabilities. Of course universities were segregated and provision was made for white teachers.

Student teaching, practicums and internships are being made available to teachers at various universities and inclusive education is receiving a lot of attention. Teachers are certified with four-year degree programmes which include practicums and teacher training at school sites. Bursaries will be offered to teachers as part of the National Bursary Scheme if current negotiations come to fruition.

Teacher Development Priorities in Inclusive Education include the following:

Focus 1: Training all teachers on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS) and Curriculum Differentiation – CAPS training and one per school (2012–2014).

Focus 2: Improving specialized skills – visual impairment, deaf and hard of hearing, autism, intellectual disability, communication disorders, cerebral palsy – short courses and bursaries for Higher Education Institutions accredited courses (2012–2014).

Focus 3: District support teams – effective management of special schools, full-service schools and supporting implementation of inclusion at all levels (guidelines training) (2012).

PERSPECTIVE ON THE PROGRESS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION

In assessing the progress of the Department of Education’s White Paper Six, a number of factors have to be considered. South Africa became a democracy about 18 years ago and merged 19 separate ethic and provincial departments into one unitary system of education. New appointments were made in the various state departments and there was a total transformation in terms of demographics, leadership and policy.

Whilst inclusive education was embraced as an ideology and practice by a large majority of South Africans, there remain several challenges. Many people who embraced inclusive education were the marginalized, black people, progressive white people and those that saw merit in the concept based on educational thinking. However, the inclusive system had to be implemented in an education system that did not have a sound and developed practices in the majority of schools that previously were characterized as disadvantaged. Another challenge related to the fact that the expertise in the field were in the hands of people who promoted special education. The majority of the structures and organizations in the field of special education were led by people who promoted special education. The transformation of knowledge and organizations was a huge stumbling block in terms of advancing inclusive education. Paradigmatic change is a difficult concept. However, to advance paradigmatic change in an environment where people’s views were so entrenched in the opposing discourse is a gargantuan task.

Within this context seven white papers were developed and implemented. Table 3 provides the foci of the different White Papers.

Table 3. Foci of South Africa’s Department of Education White Papers.

| White Paper |

Foci |

| White Paper 1 |

First White Paper of the Democratic Era that lays the framework for education and training in South Africa |

| White Paper 2 |

Organization, Funding and Governance of Schools |

| White Paper 3 |

Transformation of Higher Education |

| White Paper 4 |

Further Education and Training Colleges |

| White Paper 5 |

Early Childhood Education |

| White Paper 6 |

Inclusive Education |

| White Paper 7 |

e-Learning |

In South Africa’s relatively new democracy, there has been a major commitment in principle to special education or inclusive education. Many South Africans who came into power in the new democracy developed a demonstrated passion and commitment to inclusive education as a major part component to change the system. This passion emerges from the fact that substantial numbers of South Africans operated in the margins and cracks of Apartheid society.

The context into which White Paper Six was implemented differed but presented a range of challenges. A closer look at the education profile within the province of the Western Cape, the second richest province, provides some sense of the challenges facing policy implementation. According to the Human Capital Strategy developed by the provincial education department, only 23.4% of the population complete grade 12 (final school year), 36.5% drop out during the secondary school phase, only 7.9% complete primary education, 15.2% drop out during the primary phase and 5.7% of the population have no schooling. Looking at this across racial divides, it is evident that enrolment and completion of school to the age of 17 years is highest amongst the whites (at 100%), with the enrolment and completion is significantly lower amongst the African population, and still lower amongst Coloured adolescents. For those who are at school currently, only 37% of learners at grade 3 level are achieving grade-appropriate literacy and numeracy levels while at grade 6 level, numeracy performance drops to 15%, and literacy performance to 35%. These statistics are very problematic especially considering that the Western Cape’s education department receives 38.1% of the provincial budget (Western Cape Education Department, 2007). It is evident that these children are not receiving a high quality education in spite of the ample funding that occurs.

It is quite logical given South Africa’s history to conclude that the poorest children are black. It is also logical conclude that black poor children are the ones that experience the least success in the education system. After 15 years of funding education on a pro-poor basis with the emphasis on equity, it seems there is much more work to do if inclusion has to become a reality. The challenge is to break the cycle of failure and poverty using education as a point of departure. The high dropout rate and the low pass rates in literacy and numeracy suggests a relationship between parents level of education referred to above and school results.

In the light of the above discussion, it becomes obvious that one of the main interventions of White Paper Six was to introduce the notion of barriers to learning and the introduction of systemic issues instead of focussing mainly on individual deficits as the only challenge of special needs education. Many learners experience barriers to learning or drop out primarily because of the inability of the system to recognize and accommodate the diverse range of learning needs typically through inaccessible physical plants, curricula that is geared for general education students, ineffective assessment, insufficient learning materials and ineffective instructional methodologies. The approach advocated in White Paper Six is fundamentally different from traditional ones that assume that barriers to learning reside primarily within the learner and accordingly, learner support should take the form of a specialist, typically medical interventions (Department of Education, 2001, p. 60). The notion that performance could be affected not only by individual weaknesses but systemic weaknesses was introduced by White Paper Six. This shift in thinking could be characterized as follows. Different learning needs may also arise because of:

• Negative attitudes to and stereotyping of difference.

• An inflexible curriculum.

• Inappropriate languages or language of learning and teaching.

• Inappropriate communication.

• Inaccessible and unsafe built environments.

• Inappropriate and inadequate support services.

• Inadequate policies and legislation.

• The non-recognition and non-involvement of parents.

• Inadequately and inappropriately trained education managers and educators. (Department of Education, 2001, p. 60)

In the long term, understanding the above weaknesses to effective learning and systemic challenges may assist educators in addressing challenges facing the South Africa’s education system. Positively, after a decade, the educational policy process and understandings are taking hold. Further, current performance suggests that South Africa has to consolidate and entrench the insights generated by White Paper Six.

South Africa has many challenges and there is a considerable amount of work that is yet to be done. However, a 2012 Department of Basic Education (previously Department of Education) report indicated that the following has been achieved with regarding to implementing White Paper Six:

- Piloted the implementation of White Paper Six through a Field Test in 30 districts, 30 special schools and 30 designated full-service schools;

- Developed the screening, identification, assessment and support (SIAS) strategy for early identification of learning difficulties and support;

- Developed Inclusive Learning Programmes to guide the system on how to deal with disabilities in the classroom;

- Developed Funding Principles to guide provinces on how to fund the implementation of White Paper Six as an interim measure;

- Submitted two funding bids to Treasury for the Expansion of Inclusive Education Programme from which R1.5bn was allocated for 2008 and R300m for 2009 on Equitable Share basis;

- Converted 10 ordinary schools to full-service schools;

- Incorporated inclusivity principles in all curriculum training;

- Trained 200 district officials related to educational aspects for students with visual impairment and hearing impairment;

- Developed Guidelines for Responding to Learner Diversity in the Classroom through the National Curriculum Statement and orientated: 2,474 district officials and grade 10 subject advisors in 2011; 110 stakeholders in 2011; 3,035 district officials and subject advisors for grade 11 in 2012; 163 stakeholders and special schools lead teachers in 2012; and 968 district officials and subject advisors for grades 4–6 in 2012;

- Is developing the South African Sign Language curriculum as subject for grades R-12;

- Has developed a framework for qualifications pathways at NQF level 1 for learners with moderate and severe intellectual disability;

- Is developing an Action Plan to provide access to education for out-of-school children and youth including those with severe and profound intellectual impairments;

- 98 Special Schools have been converted to Special Schools as Resource Centres;

- 25 New Special Schools have been built;

- 225 Full-Service Schools have been created;

- District-Based Support Teams have been created across the country.

After a little more than a decade of implementation, it is clear that progress has been achieved; however, the achievement of learners and learning outcomes is not at a desirable level.

CHALLENGES THAT REMAIN

It must be noted that the above pilot study was initially envisaged as a three-year pilot but was concluded within a ten-year period. Whilst government committed itself to completing the pilot in three years, a number of factors contributed to delaying the implementation. These included provinces not dedicating budgets to advance the pilot, staff turnover in the Department of Basic Education, lack of human resource capacity in the provinces and in general a lack of prioritizing given the number of pressing priorities in the provinces.

The Department of Basic Education (DBE) in South Africa committed 2013 to the entrenchment of Inclusive Education thus calling 2013 the year of inclusion. This was a very bold approach by the education authorities. As mentioned earlier, there is much more to do for inclusive education to be successful in South Africa. Whilst progress in the area of inclusive education is at a theoretical stage, the planning and the beginning steps of White Paper Six has been achieved. It is obvious that more work has to be done in the area of teacher education, human resource development, building and developing full-service schools, support and creating special schools as resource centres and empowering district-based support teams. The following presentation to the education standing committee (Department of Basic Education, 2012) reveals the limitations of the implementation:

- Analysis found glaring disparities in the provision of access to specialist services to schools across provinces and within each in terms of types of the professionals;

- There is a huge lack of specialist professionals and in three of South Africa’s provinces the availability of specialists is below 0.5%. These provinces are yet to budget for inclusive education. There is a lack of therapists, psychologists, social workers and professional nurses;

- The ratio for teachers without knowledge of South African Sign Language (21.8%) is higher than that for teachers without knowledge of visual impairment (10.9%). Areas of deafness and visual impairment appear to experience major challenges. Although South African Sign Language development has begun, this is one of the most neglected sectors.

The lack of quality and trained staff is a major problem that hinders the further development of Inclusive Education/Special Education in South Africa. Specialists are central to the assessment and identification process. Availability of therapists is also critical for assessment of learners for provision of assistive devices and technology particularly for students with physical disabilities. If the three provinces that have not budgeted for the expansion of Inclusive Education do not occur, White Paper Six will ultimately fail in these provinces. According to the report made by the Department of Basic Education (2012) to the standing committee, visual impairment and deafness are isolated because they are the highly specialized compared to other disabilities that largely depend on Curriculum Differentiation. The report also cautioned about appropriate and relevant conversion of ordinary schools to full-service schools. Specifically, the report stressed that a conversion is more than making schools environmentally accessible for learners with physical disabilities as there is an accompanying need for an inclusive education ethos. Ultimately, the report calls for provinces to get more involved in the inclusive education process through adequate budgeting, increased advocacy and effective training.

At a general level, it seems that the envisaged White paper Six educational shift in paradigm has been largely underestimated. Paradigm shifts are complex and ambitious projects and poor results in the South African education system suggest that deeper training of teachers should take place to address the challenge of poverty and education. If poor learners and poor achievers are to be advanced in the system, teachers need effective; special education knowledge based instructional tools that will create a different consciousness within the school cultural so that inclusive education can flourish.

CONCLUSION

For a developing country and a relatively young democracy, South Africa has made some bold attempts at moving towards an inclusive education system. The country’s progress in this endeavour is noted but not currently sufficient given the documented learning outcomes of South Africa’s learners in their formative years.

While the 2013 year dedicated to inclusive education has led to advancement in achieving White Paper Six goals, it also pointed out the needs to focus on the employment of specialists and support personnel. Psychologists, therapists and related personnel are indispensable to successful inclusive education particularly for full-service schools, special schools as resource centres and district-based support teams. The results of academic achievement and advancement in the early grades of schooling suggest that not much progress has been made with regard to the paradigm shifts anticipated in White Paper Six concerning barriers to learning. Teacher training should focus on content knowledge but also provide teachers with effective instructional and intellectual tools to deal with poverty. The alienation of South African children who experience barriers to learning due to hearing and visual impairments is problematic. This cannot continue as any human rights culture should ensure that learners who are hearing or visually impaired should be at the centre of the inclusive education process.

REFERENCES

Behr, A. L. (1980, 1984). New perspectives in South African education. Durban, South Africa: Butterworths.

Department of Basic Education. (2012). Presentation to standing committee. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education.

Department of Education. (1996). White paper on education and training. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Department of Education. (1997). Quality education for all. Report of the national commission for special education needs and training and national committee for education support services. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2001). Education white paper 6 on special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Cape Town, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2003). Outcomes-based education in South Africa: Background information for educators. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2005). Conceptual and operational guidelines for district based support teams. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2007). Guidelines to ensure quality education and support in special schools and special school resource centres. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2010). Guidelines for full service schools/inclusive schools. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Education.

Disability Desk: Office of the Deputy State President. (1997). Integrated national disability strategy document. Pretoria, South Africa: Office of the Deputy State President.

Fick, M. L. (1939). An individual scale of general intelligence for South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: SA Council for Educational and Social Research.

Fulcher, G. (1989). Disabling policies? A comparative approach to education policy and disability. London, UK: Farmer Press.

Government of South Africa. (2001). Census. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printer.

High Court of South Africa. (2010). Western Cape forum for intellectual disability vs. Government of South Africa. Case 18678. Cape Town, South Africa.

Legal Resources Centre. (2009). Update in the matter of Kyle Springate. Bulletin. Retrieved from www.lrc.org.za/

Naicker, S. M. (1999). Curriculum 2005: A space for all, An introduction to inclusive education. Cape Town, South Africa: Tafelburg.