SPECIAL EDUCATION TODAY IN ISRAEL

Hagit Ari-Am and Thomas P.Gumpel

ABSTRACT

This chapter describes the current state of special education in Israel as well as what the future holds with possible solutions to improve services for individuals with disabilities. Israel is a very complex society and, as such, the educational system is very complex as well. The development of the special education system in Israel will be described as well as the current policies. In addition, different service delivery models will be explained. Inclusionary practices in Israel will be discussed as well as the prevalence and incidence rates of different disabilities in Israel and how they have changed over time. Finally, different strategies and models for implementation of services will be described and the importance of teacher training to meet student needs will be highlighted.

The Israeli education system in general, and the special education system, in particular, face complex challenges. Israel is a complex society, fractured into different sectors where each sector pushes its own agenda and attempts to dictate government policy. Israel is also an immigrant country with a large indigenous population and is engaged in an ongoing political, national, and military conflict with enemies from without and competing national narratives from within. It would be inconceivable that these monumental stresses would not impact on society’s greatest instrument of socialization and homogenization: the educational system. In all countries, the provision of special services to children with special educational needs is a civil and human rights issue, and so these fractures in Israeli society are also amplified in the special educational system. As we shall see, this small country faces a series of challenges which are unique to the Israeli context, as well as other challenges which are common to other ethnically diverse nations.

The State of Israel is a small country (20,770 sq. km.) and is slightly smaller than New Jersey, with a primarily industrial and service oriented economy (96.5%). The population of 8 million is composed of two primary ethnic groups: 75.3% Jewish and 20.7% Israeli-Palestinians (also called Israeli-Arabs1) who are either Muslims or Christians; Druze and Bedouins are two ethnic groups subsumed within the Arab sector. Four primary religions are represented in the country: Jewish (75.3%), Muslim (17.2% – predominately Sunni Muslim), Christian (2%), and Druze (1.7%) (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012b). In this rich ethnic mosaic, the Jewish population can be roughly divided into four groups: secular, traditional (keeps some sort of Jewish traditions and holidays and would be considered “reform” or “conservative” Judaism in North America), religious (would be considered “orthodox” Judaism in North America, men are noticeably visible by the knitted yarmulke), and the ultra-orthodox (who live in separate communities, often known as “Hassidic Jews” in North America, men are noticeably visible by their black suits, hats, and beards). The Jewish population is also divided into Ashkenazi (of European descent) and Sephardic (also called Mizrahim and are of Middle Eastern descent) Jews. The ultra-orthodox are divided into countless subgroups, some Ashkenazi and some Sephardic (Gumpel, 2011).

SPECIAL EDUCATION IN ISRAEL

The birth of the Israeli special education system can be divided into three historical periods: (a) developments which took place during the period when Ottoman Syria (1516–1918, which included Palestine) was ruled by the Ottoman Empire (1453–1918) and was divided into three primary provinces or sanjaks (Sanjak of Jerusalem, Sanjak of Balqa, Sanjak of Acre); the Sanjak of Jerusalem was exposed to increased European influence since the cessation of hostilities in the Crimean War (1853–1856), as Ottoman Syria was forced to allow European powers to purchase land and assume rights in the Holy Land; (b) the period following the end of the First World War in which the United Kingdom assumed control of Palestine as a British Mandate (1918–1948) and during which political Zionism, which called for the establishment of a Jewish state as the national (or binational) and secular homeland of the Jewish people; and (c) the period since the establishment of the modern State of Israel in 1948.

The first special education institutions in Palestine (the term to define the pre-state entity) were established early in the 20th century, during the Ottoman Period, mainly by physicians who received funding from organizations and philanthropists. The Jewish Institute for the Blind was established in Jerusalem in 1902, by Nachum Natanzon, a philanthropist and by Abraham Mozes Lontsz who lost his sight as a young man and later published the first Hebrew books in Braille. Concurrently, the Arab Organization for the Welfare of the Blind was established in Jerusalem, by Sobhi El-Dajani, a member of a family of physicians, who was blind himself and directed the institute with his wife and received support from the British government. At roughly the same time, two other institutes for visually impaired Arab students were also founded in Ramallah (for girls) and in Beit-G’an, in the northern part of the country (Sadeh, 2003).

The trend to develop special educational frameworks for sensory impaired children continued during the period of the British Mandate: in 1932 the first school for deaf and hearing impaired children was opened in Jerusalem through the support of the Alliance Israélite Universelle. The school, which is still in operation, has always served both Jewish and Arab children. Concurrently, Dr. Mordechai Birchiyahu, began to work with and teach “difficult to educate” and “nervous” children in the new city of Tel Aviv. Birchiyahu also established an institution for children with intellectual disabilities (ID), with the support of the head of the local educational department at the time, Shoshana Persitz, in 1929; “Netzah Israel” was active for 60 years (until 1989, Sachs, Levian, & Weiszkopf, 1992; Sadeh, 2003). In 1939, another school was established in Jerusalem: the David Yellin School served children with various disabilities.

Massive migration along with the United Nations declaration of November 29, 1947, changed Palestine forever by creating a de jure Jewish state through demographic transformation, land acquisition, development of a separate Jewish economy, and the development of separate social, political, economic, and educational institutions (Farsoun & Zacharia, 1977). The shift in balance from an unimportant backwater province of the Ottoman empire, consisting only of a handful of impoverished groups of Jews in the late 19th and early 20th century, to a fledgling modern nation with a clear Europeanized majority created a European style hegemony in all cultural and national institutions which was, of course, reflected in the structure and goals of the educational system of the time.

EDUCATIONAL POLICY IN ISRAEL

Following the establishment of the State of Israel, in 1948, the educational system grew rapidly. A major challenge in becoming a viable and stable Jewish state was the need to recreate a Jewish majority in Palestine where none had existed for 2,000 years. During this time, the seeds of today’s primary and basic dilemmas of modern Israeli society were sown, issues whose trajectories are still visible today. Since achieving independence, the country’s leaders have repeatedly declared that a primary goal of the educational system has been to reduce socioeconomic gaps between different segments of the population on an inter-ethnic (i.e., Jewish vs. Arab allocations in education) and an intra-ethnic (Ashkenizim vs. Mizrachim, secular vs. religious) level. These “gaps” exist on a myriad of economic, cultural, and legal levels (Gumpel, 2011). For instance, marked differences are evident in demographic comparisons between Jewish and Arab citizens. Israeli-Palestinian families are larger than their Jewish compatriots (in 2010, 11% of Israeli-Palestinian families had more than five children vs. only 3% of Jewish households, Meyers – JDC – Brookdale Institute, 2012). Likewise, poverty rates between the two groups differ: in 2012, 53% of Israeli-Palestinian families, and 66% of Israeli-Palestinian children lived in poverty versus 14% and 24%, respectively, for the Jewish population. Disability rates also differ between the two groups. In 2012 the prevalence rates for severe disabilities among children was 5% for Israeli-Palestinian and 3% for Jewish children (Meyers – JDC – Brookdale Institute, 2012).

Aside from the declarative nature of these intentions, educational policy has rarely been discussed on a systemic level (Shmueli, 2003). Disparity in educational performance also exists between the primary Jewish groups and between Jews and Arabs (OECD, 2009). For instance, in 2011, 70.4% of all Jewish high schools students were eligible for their high school matriculation diploma, as compared to a 52.5% rate for Arab high school students; these numbers have remained fairly stable since 1995 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012b) and are even more disturbing in Jerusalem, the capital. Despite an 8% dropout rate among youth in West Jerusalem, the dropout rate in occupied East Jerusalem2 approaches 50% (Wargen, 2006).

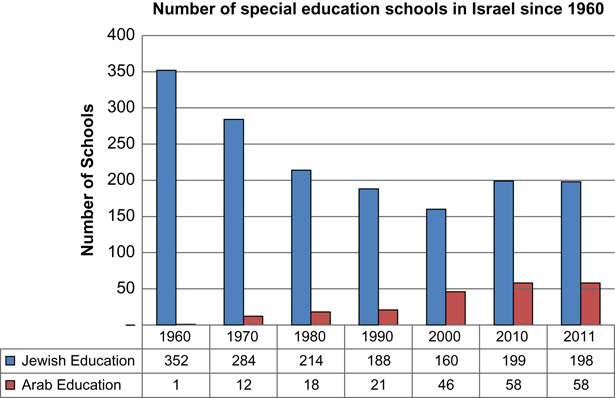

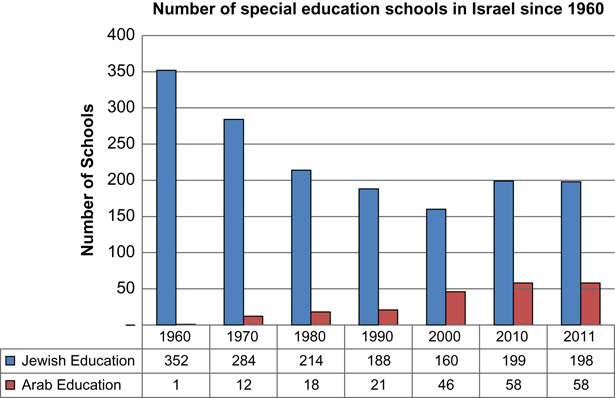

In 1960 there were 353 special education schools in Israel and only one of them was Arab. Over the succeeding decades, Israel has witnessed a continued reduction of segregated special education schools in the Jewish education system with a concomitant increase of special schools in Arab education (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012b). Due to a myriad of reasons too numerous to explore here, educational expenditures in the Arab sectors in Israel have trailed those in the Jewish sectors. Figure 1 shows the disparities in the provision of special educational frameworks for these two groups. Despite the fact that Jewish educational institutions were historically funded more than those of non-Jewish groups, funding and resource gaps have been slowly closing since the 1980s. Even though these gaps are being reduced, Israeli-Palestinian children are still underserved; whereas in 2011 the ratio of special education schools for each Jewish child was 1:7,692, for Israeli-Palestinian it was 1:8,695 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012a).

Fig. 1. Number of Special Education Schools for Jewish and Israeli-Palestinian Children from 1960 to 2011.

The Israeli educational system is controlled by a strong central bureaucracy located in Jerusalem and is run by the Ministry of Education (MoE) (Gumpel, 2011), which has undergone substantial changes over the last 65 years. The special education system is directed from the ministry via the Division of Special Education (DSE). As a result of the complicated political reality in Israel, educational policy is subservient to different, often conflicting, political and demographical considerations (Avissar, Moshe, & Licht, 2013) as frequent political changes make it difficult to formulate long-term policies. For example, a recent reform to set a clear “strategic plan” was made by the MoE in 2011 where three major goals and 11 operational targets were outlined (e.g., enhancing Zionist ideology along with Jewish, democratic, and social values, reducing violence and creating a positive school atmosphere, improving educational achievements, reducing achievement gaps between different demographic groups, improving teacher’ status, and encouraging efficacy in the system). The following year, in 2012, one more major aim was added in a declared intention to strengthen schools’ ability to include students with different special educational needs and abilities and to reduce referrals to special education settings (the so-called “The 12th Target – Inclusion” mandate, Avissar et al., 2013).

Inclusionary Practices

The special education system in Israel has historically been dominated by neurologists, neuropsychologists, pediatricians, and psychologists working in a medical and pathology-based categorical model of impairment where all children receiving special education services are divided into 12 different eligibility categories based on their primary disability (Gumpel, 2011). Historically, the first step in changing the policy toward educating students with special needs was the establishment of a ministerial panel of experts to reconsider the definition of a child with special needs and the purpose of special education (known as the “Cohen-Raz Committee,” 19763 in Ronen, 1982). The committee recommended, for the first time in Israel, that a student would be placed in a special school not only because of his or her disability, but also by his or her special needs and level of functioning (Marom, Bar-Siman Tov, Karon, & Koren, 2006). Despite the panel’s recommendations, discussion of integration and inclusion only began to gain momentum following legislation of the 1988 Special Education Law (SEL) and the implementation of the law in the early 1990s, as many children who previously received services in segregated settings began to receive services within the general education framework (Avissar & Layser, 2000; Comptroller’s Office, 2001; Gumpel, 2011; Margalit, 1999). Like much of Israeli society, special education procedures prior to the passage of the SEL of 1988 (“Special Education Law of 4758,” Knesset, 1988) were based on an informal and personal form of negotiation between the educational system, the child’s family, and the Ministry of Education (Gumpel, 1996). Services were provided under the more general auspices of the Compulsory Education Law of 1949 and the State Education Law of 1953. Today, over 30 years after its passage, the SEL of 1988 remains the foundation of Israeli special education and marks a turning point in the provision of special education services to children and adolescents with special needs. As a result of the SEL, the special educational system has slowly shifted to a more inclusionary system with a set of bureaucratic safeguards to ensure that all children receive a quality education.

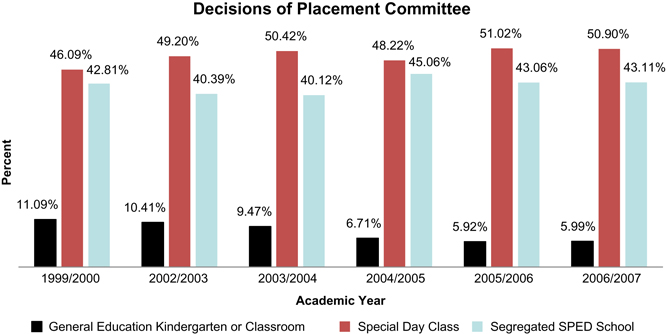

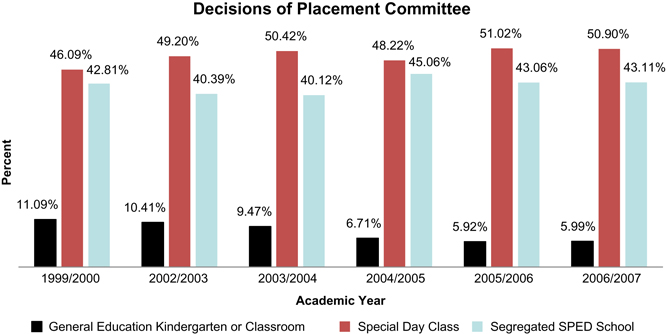

Currently, the MoE has adopted three models of inclusionary special education: (a) the individual inclusion of students within general education classes and kindergartens where the majority of learners do not have learning disabilities (LDs); (b) self-contained classes within general education schools where the students have identified multiple LDs as well as Emotional and Behavioral Disorders (EBD), Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), and mild ID; and (c) inclusionary classes, with a limited number of special needs students and two teachers (a primary “homeroom” teacher and a special education teacher) who work both together and separately (this model is not common, and exists primarily in kindergartens). Despite these guidelines, the number of inclusionary placements has gotten smaller over the last decade, with a fairly consistent downward trend in inclusionary placements (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Decisions of Placement Committees, 1999–2000 through 2006–2007 Academic Years.

Prevalence and Incident Rates

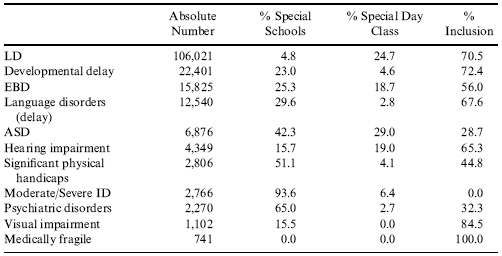

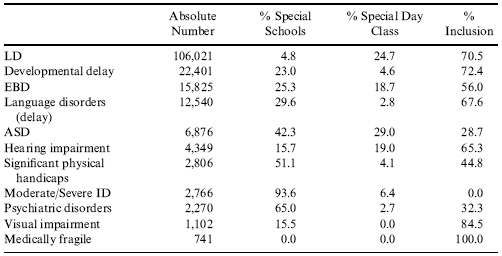

In the 2011–2012 academic year, there were 2,576,900 children in Israel; approximately 75% were Jewish and 25% Israeli-Palestinians. For all students, 330,000 (12.8%) children had identified disabilities or chronic diseases, according to estimations of the National Council for the Child (NCC) (Zionit & Ben-Arie, 2012). In that same year, 203,200 children (7.9%) were identified by the MoE as having special educational needs, 64.5% were included in general educational settings, 18.6% studied in self-contained classes within general education schools, and 16.9% of them studied in segregated schools. Table 1 shows prevalence rates of ten primary disability categories in the three types of special educational placements: inclusionary classrooms, special day classes in general education schools, and segregated special education schools (Zionit & Ben-Arie, 2012). LD is the largest category of students and accounts for 51.4% of all students with special needs; however, this number refers only to students who are identified as presenting with complex or multiple LDs, and are supported by special education services (most “mild” LDs are never formally identified through special education placement committees). Students with LDs are also the largest group in inclusionary and self-contained classes. Other categories of special needs students are those with EBD at 7.6%, developmental delays (10.8%), and language delays (6%); for both of these two groups, 70% of identified children receive services in early childhood settings (Zionit & Ben-Arie, 2012).

Table 1. Frequencies of Selected Disability Groups Receiving Services from the Ministry of Education in the 2009–2010 Academic Year, Listed in Order of Prevalence.

Source: Zionit, Berman, and Ben-Arie (2009).

Table 1 also clearly shows that educational placements in Israel are guided by a categorical system where inclusionary resources are available depending on the student’s diagnostic category as opposed to his or her individual functional level. General education placements are implemented primarily among children with LDs where 70.5% of these students are included in general education settings, similar to the placement of students with developmental (72.4%) or language (70.5%) delays. Slightly more than a half of students with EBD are included (56%), and less than a half (44.8%) of students with cerebral palsy/severe physical handicaps are included. Nearly a third of students with psychiatric disorders (32.3%), and ASD (28.7%) are included individually in general educational settings.

CHANGES IN RATES OF DISABILITIES

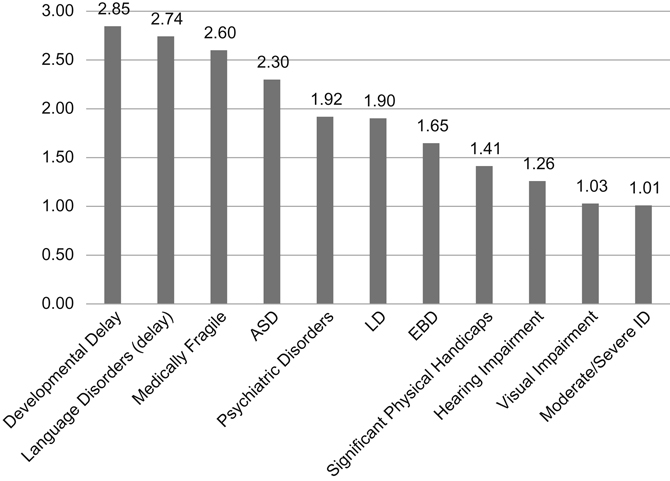

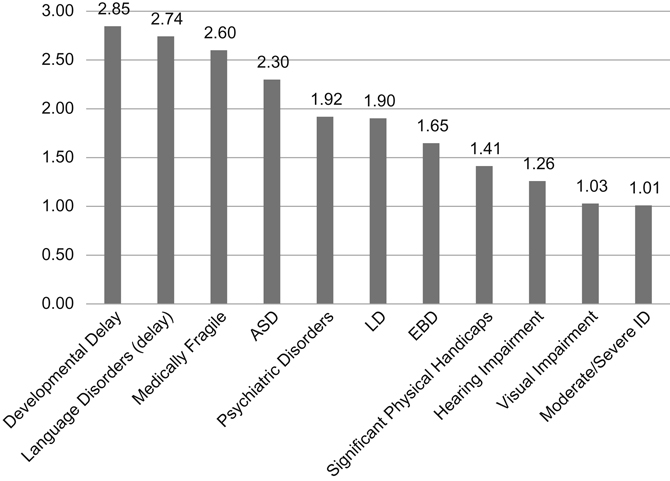

Figure 3 shows the prevalence rates of selected disabilities since 2006 (the first year that the Central Bureau of Statistics published detailed data on each disability) cross-tabulated with type of placement. While in 2012 nearly 8% of Israeli students were defined as students with special needs, six years earlier only 5.5% were identified as such. The total increase of students in the educational system was of 1.2 during this period, while the increase in the number of special education students was of 1.74.

Fig. 3. Changes in Rate of Disabilities since 2006. The Increasing Rate of General Education = 1.21, Overall Increase of Special Education = 1.74.

Three different types of prevalence increases are evident since 2006. First, certain disability groups have kept pace with growth rate of the general education system (moderate and profound ID, sensory impairments, and physical disabilities). A second trend is evident in categories which have almost doubled their size relative to the general educational trends (i.e., LD, EBD, and psychiatric disorders). For instance, the number of students with diagnosed LDs or psychiatric disorders has increased by 92% and 90%, respectively, during this same period. The third data trend includes those disability groups whose identification and placement in the special education system has increased to a much larger extent: at times over 200% growth (mild IDs and developmental delays, ASD and language disorders, and medically fragile children). This extreme growth is well illustrated by the change rates of two separate categories which increased dramatically over the last several years: ASD and LD.

CASE STUDY: CHANGES IN PREVALENCE OF STUDENTS DIAGNOSED WITH AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDER

Currently, due to significant methodological differences across studies, there is no agreement between Israeli authorities and researchers regarding the prevalence of ASD in Israel. A report published in 2010 (Tseva, 2012) in order to estimate the incidence of ASD in Israel and to correlate prevalence rates and other demographic variables, shows a dramatic increase between the 1980s and 2004. The increase was recorded in all populations in Israel, yet most pronounced in the Jewish populations (due to apparent under-diagnosis in other ethnic groups). Among the latter, rates increased from 1.2 per 1,000 among children born in 1986–1987 to more than 3.6 per 1,000 in 2003. The study database included two Israeli national registries: The Israeli Ministry of Social Affairs, which is the official agency responsible for welfare of individuals with autism in Israel and the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), as a source of annual numbers of live births and on infant mortality (defined as death during the first 12 months, between 1986 and 2005), stratified by gender and ethnicity (Gal, Abiri, Reichenberg, Gabis, & Gross, 2012). The increase in prevalence rates showed a strong gender effect. Among males, the average rate increased from 2.3 per 1,000 in 1986–1990 to 5.1 per 1,000 in 2000–2004, while among girls a modest increase was seen from an average of 0.53 per 1,000 in 1986–1990 to 1.0 per 1,000 in 2000–2004; the male to female ratio gradually increased during the study period from 4.8:1 in 1986–1990 to 6.5:1 in 2000–2004. Another recent Israeli study examined physician records rather than governmental reports or educational sources of ASD, in order to calculate the prevalence and incidence of ASD over seven years (Davidovitch, Hemo, Manning-Courtney, & Fombonne, 2012). All children in this report were registered in one of the Israel health maintenance organizations (HMO) which provide services to approximately 25% of Israeli population.4 In 2010 the prevalence of children diagnosed with ASD was 4.8 per 1,000; boys were 7.8 per 1,000 and girls were 1.6 per 1,000 (corresponding to a male:female ratio of 5.2:1). The study found a significantly lower prevalence of ASD for low SES group as compared to other income groups. Further, prevalence was lower for both Israeli-Arabs (1.2 per 1,000) and ultra-orthodox Jews (2.6 per 1,000) as compared to the rest of the population (Davidovitch et al., 2012).

Generally, despite a significant increase in the last two decades, prevalence rates in Israel are lower as compared to US figures. One possible explanation is that the lower reported prevalence is related to more strict diagnostic criteria in Israel: children younger than six years of age are evaluated at local community Child Developmental Centers where a diagnosis is provided by a multidisciplinary team consisting of at least two specialists with different backgrounds (e.g., a child psychologist and a specialist in pediatric neurology and development) and are conducted over several meetings. Currently, Ministry of Health regulations rely on DSM-IV criteria for ASD; however, new regulations are currently being rewritten to apply DSM-5 criteria. For children older than six years of age, who are not referred to a Child Developmental Center, new health regulations (established in 2008) require that an ASD diagnosis be made only after two separate evaluations (one from a specialist in pediatric neurology and development, and the other from a clinical pediatric psychologist). Physicians and psychologists are required to delineate how each child’s symptoms match the DSM-IV criteria (Davidovitch et al., 2012).

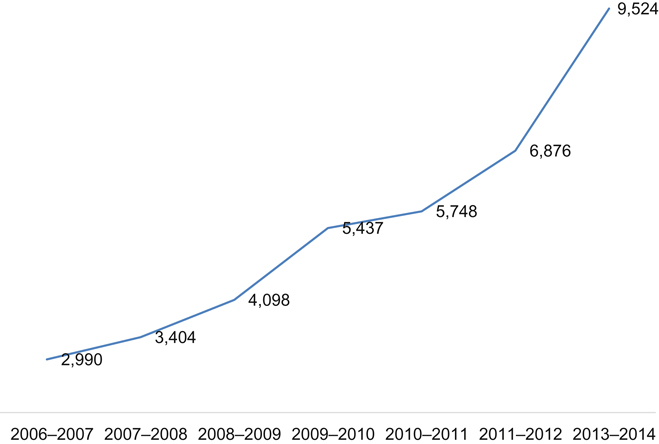

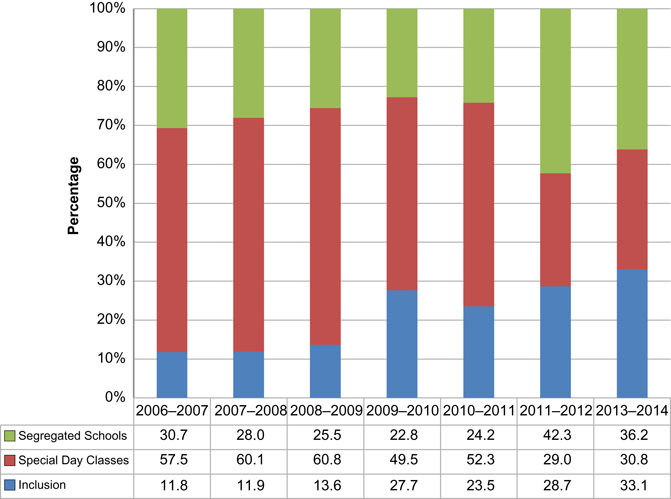

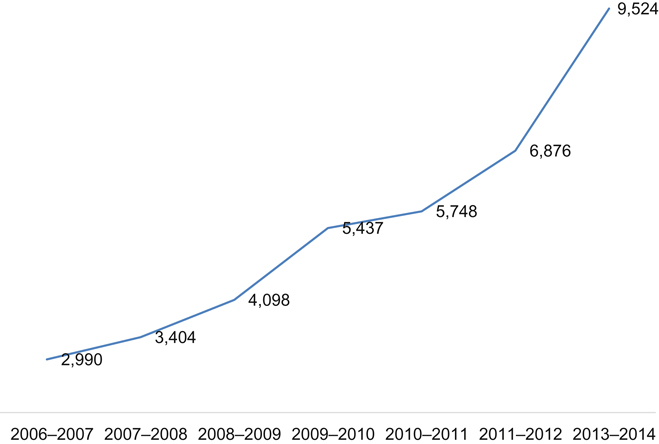

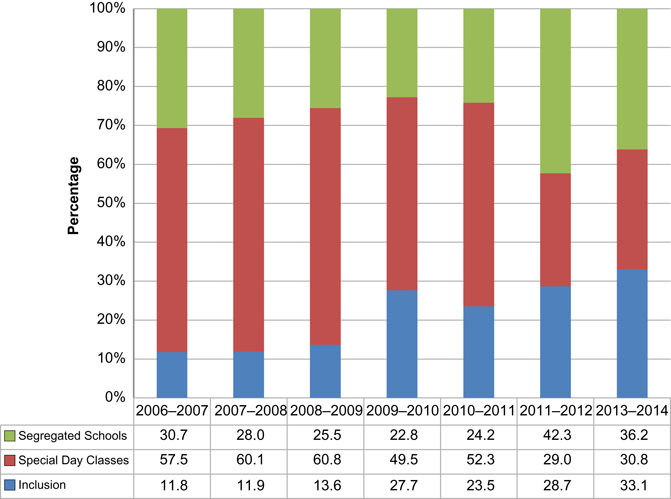

According to the MoE, there were 2,990 students with ASD in the educational system in the 2006–2007 academic year, while eight years later, the total number of ASD students increased by 318% to 9,524 (see Fig. 4). When considering the placements of students diagnosed with ASD during these years (see Fig. 5), one can see the increase of individual inclusion and placements from slightly over one-tenth in 2006–2007 to almost one-third in 2011–2012. A small reduction of students in special schools is apparent between 2006 and 2007, 30.7% to 2010–2011, 24.2%, and a sharp increase in 2011–2012. This increase is, apparently, artificial and a product of changes in the way data are currently collected. Following a correction, the percentage of ASD students in special schools reduced to 23.6%, while placement in special classes remains quite stable at 47%.

Fig. 4. Total Number of Students Defined as ASD by MOE, between 2006 and 2012.

Fig. 5. Percentages of Students with ASD in Different Settings between 2006 and 2014.

PROMINENT EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTIONS

DSE guidelines specify that (a) every student is entitled to his or her education and participation in his or her community; (b) every student is entitled to access to resources which will promote self-realization and the development of talents and skills in order to develop skills; (c) every student and his or her family must be involved in planning current and life-long instructional goals; (d) the educational system must respect differences among students with disabilities; and (e) teachers must be committed to cooperative educational processes and professional standards (Avissar & Bav, 2010; Pen & Tal, 2006).

Services are provided in three main frameworks, special kindergartens and schools, self-contained classes, and individual inclusion in general education schools. Individualized Educational Programs (IEPs) for every student with special needs are mandated by the Special Education Law of 1988 and its revision of 2002. The MoE differentiates between IEPs for students in enrolled in segregated schools or self-contained classes (Tala or ) and the IEP of individually included students (Techi or ), although they are similar in their components. The Tala must include a statement of the present educational performance, strengths, and educational goals in all principal academic areas: cognitive, educational, behavioral-emotional, sensory-motor, communication, and life skills. Instructional goals must be set for all relevant areas and a delineation of educational services must be provided (Director General – Ministry of Education, 7/1998) and educational staff are encouraged to invite the parents in order to solicit their input. It is “highly recommended” that the completed IEP will be delivered to the parents during the beginning and ending of the academic year, the teacher must evaluate progress and report to parents. As in the Tala, the Techi must contain statements of the present educational performance, list strengths and weaknesses, define the responsibilities of each staff member, and specify which educational services are to be provided (if the student is receiving assistance from a paraeducator, his or her role must also be specified). Unlike the Tala, however, instructional goals should be based on the general education curricula, and include the expected assignments for the students; students and their parents must be invited to the planning phase and receive a copy prior to the beginning and end of each academic year (Director General – Ministry of Education, 11/2007; Instructions Chapter D1 for Special Education Law, 4763 [Correction number 7 for Special Education Law, 1988], 2002).

EDUCATIONAL PLAN IN SEGREGATED SCHOOLS

In the late 1990s the director of the DSE convened a steering committee for planning a program for adolescents in segregated schools. The results were summarized in a series of guidelines based on a model of quality of life (Reiter, 1999), emphasizing feelings of well-being, opportunities for positive social involvement, and opportunities to achieve personal growth where individual perceptions and values – the subjective views of the person – are recognized as a key facet of quality of life (Schalock et al., 2002). These guidelines outline four domains: social education, career education; independent living in the community, and citizenship education through the use of computers. Initially, the program was designated for students with ID only; however, it has been widely implemented by all special education schools nationwide (Avissar & Bav, 2010; LEV-21, 2009).

Core Curriculum

Until the mid-1980s, the DSE viewed the general education curriculum only as a general framework, allowing teachers to adapt contents and methods. In the mid-1980s, the DSE started to plan a core curriculum along with the Curriculum Planning and Development Division in the MoE, and although cooperation was initially minimal, over time the curriculum became more systematic (Avissar & Bav, 2010). Following passage of the SEL in 1988, professional committees were also set to develop special education curricula in subjects such as mathematics, language, history, science, and physical education. In 2005, the MoE published a core curriculum for elementary schools (general and special education) and defined mandatory content to be mastered by every student in order to develop as productive citizens, able to function both cognitively and emotionally as productive adults based on learning skills and social values (Director General – Ministry of Education, 11/2005). Following the general curriculum, the DSE differentiated between individual inclusion in general education settings and segregated schools, where there is more operational freedom to adopt and adapt appropriate content. All special education schools are required to apply the Core Curriculum for special education. Schools can develop or adopt additional subjects according to their own policies and ideologies (Tal & Leshem, 2007).

Strategies for Accommodations

Three types of accommodations are recognized by the MoE: Adaptations – changes in the presentation of the educational material, including enlargement of written material, presenting the material with additional supports and classroom amplification systems; Modifications – changes in the contents of the educational program, such as a reduction of part of the material; and Alternatives – adding a unique subject requirement for the students (Tal & Leshem, 2007). Accommodations are the most frequent method employed in general education schools, including adding supplemental time, using a calculator, extended formulae page, or allowing oral answers.

RESPONSE TO INTERVENTION

Response to Intervention (RtI) is “the practice of providing high-quality instruction and interventions matched to student needs, monitoring progress frequently to make decisions about changes in instruction or goals, and applying child response data to important educational decisions” (Batsche et al., 2005). RtI models are typically composed of a minimum of the following components: (a) a continuum of evidence-based services available to all students, from universal interventions and procedures to intensive and individualized interventions; (b) decision points to determine if students are performing significantly below the level of their peers; (c) ongoing monitoring of student progress; (d) employment of more intensive or alternative interventions when students do not improve; and (e) evaluation for special education services if students do not respond to intervention instruction (Fairbanks, Sugai, Guardino, & Lathrop, 2007). In the multitier RtI model, the form of academic intervention changes at each tier, becoming more intensive as a student ascends across tiers. Increasing intensity is achieved by using more teacher-centered, systematic, and explicit instruction, conducting it more frequently, adding to its duration, creating smaller and more homogenous student groupings, or relying on instructors with greater expertise (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Lipka, 2013). There are several examples of programs applying principles of RtI in Israel. Some RtI programs were developed by the MoE, and others were developed in teacher training programs and are implemented in schools with the approval of the MoE. For example, the “Safra Model” was developed in Haifa University and is applied both in Hebrew and Arabic in elementary, middle, and high schools. The program includes teacher training in the first tier and intervention with the students in the second tier, using computerized monitoring of students’ progress. Efficacy research indicates a significant improvement of basic and advanced reading and writing processes as well as higher student motivation (Lipka, 2013). Another example is the “ELA” program (an acronym in Hebrew for “Detection, Diagnosis, Learning, and Assessment”) implemented among secondary schools and based on mapping tools to identify students with difficulties. Mapping commences at the beginning of each academic year with the administration of a diagnostic language test. When students with difficulties are identified, they receive support in multi-language subjects, like history and literature, within small groups, usually by cooperative learning strategies (Lipka, 2013). A third program is “I Can Succeed” (in Hebrew – EYAL), which is meant to promote students with learning disabilities’ academic and emotional development and prevent dropout. It is a three-year program in secondary schools under the auspices of the MoE, local municipalities, the National Insurance Institute, and teacher training programs specializing in LDs. Data are collected in the first year to identify at-risk students, and during all three years of high school students participate in weekly meetings with an educational case-manager and learn educational and personal skills (Lipka, 2013).

The operational principles of the “The 12th Target – Inclusion” (described above) are similar to those of RtI: monitoring all students and identifying those with difficulties, preparing an IEP for every student who experiences difficulties, monitoring progress and adjusting intervention, parental involvement during the entire process and the use of counselor and psychologist resources. Specific guidelines were published for preschool to elementary, middle, and high school (Ministry of Education, 2012, 2013). In preschool, for example, a professional team will be deployed at every local authority and will include the teacher, educational psychologists, preschool counselors, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and behavior analysts. The team will coordinate with the local superintendent and the director of the local municipality kindergarten department. There are also dates for monitoring progress and training educational teams and other professionals. Every school must develop a multidisciplinary team to lead the process and organize the plan as well as a training program for the educational staff, build a functional profile of every student with difficulties, intervention plans based on individual or small learning groups, accommodations and adaptations to be implemented in classes, assessment and data collection. When the interdisciplinary school team considers submitting a child’s dossier to the special education placement committee, they must first consult with the local professional committee and validate that all in-school possibilities have been exhausted (Ministry of Education, 2012, 2013). As this program was first implemented in the 2012–2013 academic year, no data are currently available regarding program efficacy.

THE INCLUSION PLAN

Mandated inclusion plans are guided by three main principles: differential services in accordance with individual needs, placement in a general educational facility based on the principle of the “least restrictive environment,” and organizational flexibility in service delivery (Avissar, 2012). The plan details four categories of supports. The first category involves teaching and learning, supplemental teaching and special services, including remedial teaching (language, mathematics, and learning strategies), ancillary professionals (creative arts therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and physical therapists), and expert teachers (for applied behavior analysis, ABA, didactic diagnostics, for visually impaired students or hearing impaired students). The second category involves accommodations and adaptations (adapting the curriculum for the student by a special education teacher), technical supports (i.e., hearing devices), and organizational supports. The third category is a combination of teaching and accommodations, such as teaching in a special environment (care center or study center), teaching within specialized facilities or teaching in a cooperative inclusionary model with both general and special teachers in the same class (usually kindergarten). The fourth support method is the provision of individual assistance by a “paraeducator.” These ancillary support personnel are only a part of the overall plan and are allocated to specific low frequency populations (ASD, psychiatric disorders, cerebral palsy and physical handicaps, moderate intellectual or developmental disability, visually impaired and blindness, and medically fragile). Support is not automatic by student diagnosis and requires an assessment of the student’s level of functioning. Levels of paraeducational support may cover between 5 and 30 hours a week, reassessed on a yearly basis. Paraeducators are employed by the local municipality who contributes 30% of their salaries (the MoE covers the remaining 70%) and typically earn minimum wage (the only employment requirement is 12 years of schooling) (Director General – Ministry of Education, 11/2007).

INTERVENTIONS FOR MAINSTREAMING STUDENTS

Matya – Organizational Resources

Following the “Margalit Report” of 2000 and the 2002 “Revision of the Special Education Law,” community resource organizations were established, called Matya. Matyaot (plural) are organizational entities in each municipality by which educational, and specifically inclusion oriented, resources are organized and allocated. The Matya structure allows for the funding of school based and itinerant teachers specializing in a wide variety of specialized skills, from behavioral specialists and consultants, to diagnosticians, and other ancillary services (Gumpel, 2011). Since the establishment of the Matyaot, they have become dominant in mediating the relationship between the MoE, the field, and local authorities. Key features include: (a) the ability to act and be an extension of the local educational authority superintendent; (b) flexibility and responsiveness to changing needs; (c) proximity to the field and familiarity with the unique characteristics of the students in order to allow the adjustment necessary assistance; (d) the ability to recruit personnel, to pool resources and transfer them according to changing needs; (e) high-level organizational ability to assist special education schools in performing their tasks, allowing them to devote more time to educational interventions; and (f) the ability to specialize in methods and special care areas needed to include students into general education settings (Director General – Ministry of Education, 12/2010).

Special Issues: Accessibility of Educational Institutes

The accessibility chapter of the Equal Rights for People with Disabilities Law (1998) was passed by the Knesset (Parliament) in 2005. This chapter requires that public places and services must be made accessible, including schools (Bizchut, 2010). However, the Minister of Education published regulations regarding accessibility and access to schools in order to facilitate individual inclusion only in 2011 (despite the fact that the law stated the regulations must be met no later than 2006). According to the MoE, 4,000 classes are now accessible for deaf and hearing impaired students (out of 31,753 or 12.6% all classrooms nationwide). The number of accessible classrooms exceeds the number of children who are deaf or hearing impaired (O. Halpern, personal communication, February 6, 2014). Regulations specify the actual accommodations required by any institution with a student or parent with disabilities, including physical or sensory disabilities (Ministry of Education, 2011). Unfortunately, the educational institution is made accessible only when a student enrolls, a procedure which may take time to complete. In addition, the law requires accessibility only of the entrance, the central area, the specific class where the child is enrolled and the nearby restroom; other public areas like the library and the schoolyard may remain inaccessible (Bizchut, 2010).

Blind and Visually Impaired Students

The population of blind and visually impaired students is one of the smallest among special needs populations in the country, 0.53% of all special needs students. The majority of students with visual impairments are included in general education settings (85%). Every school district has a “specialized Matya” for educating students with visual impairment, which is responsible for providing optimal and professional interventions (Director General – Ministry of Education, 12/2010). Each blind or visually impaired student is entitled to have the individual support of an itinerant specialized teacher. Students with visual impairments are entitled to a paraeducator, according to their level of functioning and independence. There is an increasing use of assistive technologies for students with visual impairments, such as the “Technological Set for Visually Impaired Students” which includes: a laptop, a closed circuit television camera connected to the laptop, and software to enlarge material and distance. The set is usually given to older students who can properly use it and benefit from its possibilities (Shabat, 2011). There are other resources for blind and visually impaired people in Israel, such as the Learning Center for the Blind at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the library for the blind which prints books in Braille and records audio files for students (as well as other populations who need this services, such as students with LDs).

Students with ASD

The sustained increase in the number of children diagnosed with ASD globally, as well as in Israel, requires the MoE to address the educational needs of these children in the least restrictive environment. In recent years, children with ASD are identified at younger ages and at higher rates, and their clinical management is becoming more intensive, proactive, comprehensive, and consequently, also more expensive. The Israeli health system bases most of its services on public organizations and is based on a national socialized medical model which emphasizes early intervention and prevention. “Well Baby Clinics” and “Family Health Clinics” exist in every community in Israel and are completely free; “Well Baby Clinics” begin their proactive interventions with every pregnant woman and provide pre- and post-natal care for all babies during the first few years of life. In Israel, all families receive a governmental stipend upon the birth of a baby. This stipend is used as a highly effective incentive for visiting a “Well Baby Clinic” within the first weeks of life. Further, the “National Insurance Institute Act” defines eligibility of children with specific developmental disabilities (ASD among them), for extended health services. Funding of up to three individualized treatments per week is given up until age 18 for all children diagnosed with ASD. Additional treatments may be funded by the Ministries of Health, Education, or Labor, according to the child’s age and educational setting. In addition, access to a pediatrician or nurse is unrestricted, most medications are funded with a co-payment of no more than 15%, and some specific ASD treatments are covered (Raz, Lerner-Geva, Leon, Chodick, & Gabis, 2013). From the age of six months to three years, children with ASD are eligible for early preschool special education, including at least 10 hours of individualized treatments per week, all funded by the Ministry of Labor and Social services. After age three, children are eligible for special education in preschool, kindergarten, or a school setting, funded by the MoE. However, if parents or educators opt for integration in general education settings, eligibility for treatments is more limited. Home-based programs and many educational interventions are not reimbursed; they are fully paid for by parents. Gaps in public service availability and eligibility along with medical recommendations for an intensive treatment paradigm may encourage utilization of private health services, and have significant economic and social implications (Raz et al., 2013). A recent study conducted in Israel found that despite the National Insurance Institute coverage, there is a high out-of-pocket expenditure of approximately 21% of the yearly combined family income for one child and so represents a serious economic burden (Raz et al., 2013).

Early intervention in ASD is most often provided in community center-based autism-specific early intervention preschools, using one of the main approaches in the field – ABA, DIR-Floortime, or TEACCH, or a combination of methods. Intervention teams usually include program supervisors, trained therapists, speech and language pathologists, occupational therapists, special education preschool teachers, and educational psychologists (Zachor & Ben-Itzchak, 2010; Zachor, Ben-Itzchak, Rabinovich, & Lahat, 2007). In a study conducted in Israel which compared two early intervention approaches for ASD, the students who received an ABA intervention showed significantly greater improvements than a matched group of students who received conventional educational treatments (Zachor et al., 2007). Alternatively, a more recent study did not find major differences between the two interventions, and in the group of less severe autism symptoms, there was a minor preference to a more eclectic approach (Zachor & Ben-Itzchak, 2010).

Inclusion of Students with ASD

Inclusion of students diagnosed with ASD is part of the Inclusion Plan for low frequency special needs populations, according to the SEL, the 2002 Revision, and MoE regulations. However, disparities are apparent between the inclusion of students with ASD vis-à-vis other populations; these differences are often due to strong parent organizations and support groups of these specific populations. In order to ensure quality inclusion, many families take a primary role in including their children with ASD, either by hiring professionals as program supervisors and “inclusion coordinators” (to differentiate their function from paraeducators) or by surreptitiously (and illegally) supplementing the paraeducator’s salary, or paying an extra payment per working hour and privately adding extra work hours. Of course, these courses of action are dependent on family socioeconomic levels, and so are problematic. In schools, an inclusion advisor is a professional responsible for designing the inclusion programs, presenting them to the families and the education system and guiding the inclusion coordinators who work directly with the student in the educational environment. The inclusion advisor usually meets with the inclusion coordinators on a weekly basis in order to solve ongoing problems. As part of the effort to promote individual inclusion, special courses for coordinators are offered by the major parents’ organization in Israel (Eldar, Talmor, & Wolf-Zukerman, 2010). De facto, many parents hire the assistants (or inclusion coordinators) privately and the system usually turns a blind eye.

Matyaot have ASD specialists who regularly visit the inclusive settings, some on a weekly basis, other less frequently. Matyaot also have continuing education programs for inclusive teachers and ancillary staff in designing and implementing social skills training for students with ASD. Some of the social groups are composed of included students only and others are mixed groups of students with ASD and typically developing peers. In the last decade, various courses and training programs of special interventions and treatments of children with ASD have been provided by Israeli universities, teaching colleges, and other institutions resulting in more professionals providing assistance and care for children with ASD, either in the formal educational system, healthcare centers, or in private settings with families and children.

TEACHER TRAINING

The development of a quality educational system is due to a large extent on the quality of the teachers who work in that system. Therefore, increasing teachers’ professionalism is a recurrent and central theme in the Israeli education system. This growing awareness of the importance of teacher training as a means for promoting learning outcomes and school effectiveness has led to the appointment of several national committees to investigate new ways in the training, preparation, accreditation, and compensation of teachers (Gumpel & Nir, 2005).

The “National Committee for Examining Teachers’ Status and the Status of Teaching Profession” (also known as the “Etzioni Committee”) was established by the MoE in 1979 in order to improve the quality of teacher education and to address the need for measures to strengthen teaching as a profession as well as teachers’ professional status. Among suggested measures was the provision of merit benefits to excellent teachers, an increase in the teacher’s professional autonomy, an extension of demands for the teacher’s continual professional development and academic level, and the enforcement of strict supervision of novice teachers including internship and licensure requirements (Etzioni, 1981; Ministry of Education – Culture and Sport, 2004). Fifteen years later (1994) another national committee was appointed to explore the issues related to the preparation and training of teachers in Israel (“The Committee for the Reform of Matriculation Examinations,” also known as the Ben-Pertz Committee). This committee described the deterioration of the teaching profession and teacher status despite previous efforts and emphasized five main issues in its report: (a) the allocation of teacher colleges to train teachers and to award teaching diplomas with a BA or a BEd degree; (b) the examination of the geographic dispersion of the teacher training institutions and an examination of ways to increase collaboration as a means for promoting efficiency; (c) the raising of academic entrance requirements for those applying to teacher training colleges and the improvement of candidate selection; (d) the provision of incentives for outstanding student teachers; and (e) the provision of a teaching license from the MoE to those holding an academic degree and a teaching certificate after they complete their internship. These recommendations were adopted by the MoE and were also deployed at the university level for those seeking a secondary education teaching diploma at the university level (Gumpel & Nir, 2005; Hoffman & Niderland, 2010; Knesset, 2003).

A few years later, in 2005, the government established a “National Task Force to Promote Education in Israel” (known as the “Dovrat Committee”) in order to recommend major and inclusive reforms in the education in Israel. In the section dealing with the diminishing status of teachers in the country, the committee emphasized the demand to treat teaching like every other profession, with the addition of more work hours at school and the implementation of means for gauging success in reaching educational milestones (Hoffman & Niderland, 2010). Although the committee’s reforms were never actually implemented due to opposition from the two powerful national teachers unions, parts of the recommendations were later incorporated into agreements between the government and unions in 2007 leading to current reforms in the educational system – “New Horizon” (Ofek Hadash, or for elementary schools) and “Courage to Change” (Oz Latmura or , for secondary schools) (Hoffman & Niderland, 2010).

Despite all of these attempts at reform, in Israel as in much of the western world, approximately 50% of new teachers leave the profession during their first five years of employment due to low salaries, long hours, lack of institutional support (Gavish, 2002), and pervasive school violence. In addition, according to a recent study, novice teachers in Israel experience high levels of burnout as early as the beginning of their first year of teaching, due to three main variables: a lack of appreciation and professional recognition from students, a lack of appreciation and professional recognition from public, and a lack of a collaborative and supportive work environment (Gavish & Friedman, 2010).

Another government committee tasked with reforming teacher training was convened by the Israeli Council for Higher Education: “The Committee for Establishing Guiding Principles for Teacher Training in Higher Education in Israel” (also known as the “Ariav Committee,” 2006). A major recommendation by the committee was the national implementation of the requirement of at least an undergraduate degree in education (BA or BEd) and a teacher license as a condition for employment. Prior to these recommendations (since before the founding of the State of Israel), employment was not infrequently granted to teachers with a high school diploma and a teacher’s license who were trained in a teacher’s college (akin to Normal Schools in the United States or École Normale in France). Requiring an undergraduate degree also necessitated a change in the structure and personnel in many teaching colleges in the country. Whereas, previously, instructors in these teaching colleges could include experienced teachers (without undergraduate degrees), a shift began where all teacher training personnel must possess at least a graduate degree. Over the last decade, many teacher colleges have begun to offer MA or MEd degrees, and so the Israeli Council for Higher Education now requires that all faculty members have a PhD in their area of specialty.

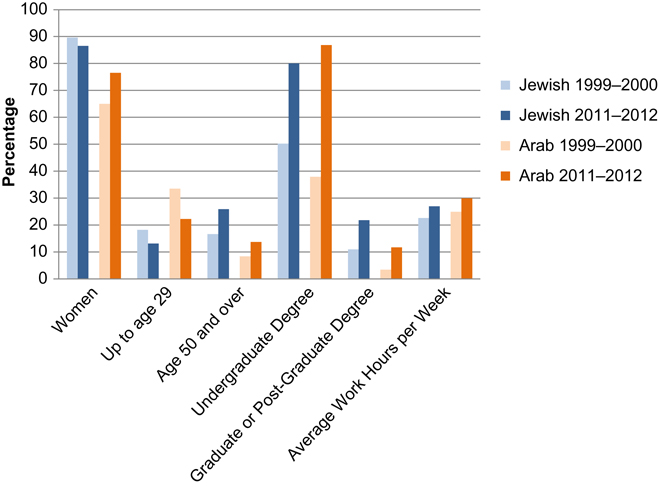

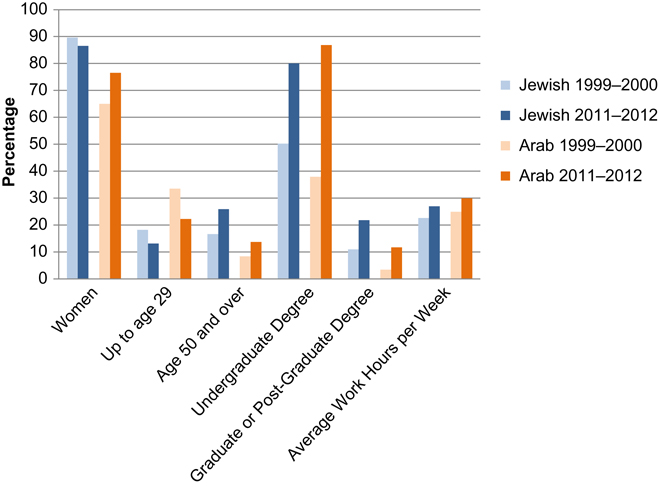

Currently, there are 5 teacher training departments in Israeli universities and 23 teacher colleges (11 secular, 9 Jewish-religious, and 3 in Arab education). About 22,000 undergraduates studied education in 2012, 20% of them specializing in special education, an overall increase of 4.5% from the previous year (Ya’acov, 2012). Nearly 3,500 graduate students were enrolled studied during this same year, a yearly increase of 11%. Figure 6 shows the recent changes in Jewish and Arab primary teaching personnel over the last decade and highlight some important differences between the two groups (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012b). For both groups, most teachers are women; however, more male teachers work in the Arab sector. Generally, both groups show a marked increase in the number of teachers with undergraduate degrees; this is most pronounced among Jewish teachers, who also lead in the number of teachers with graduate and postgraduate degrees. Further, the population of teachers has gotten older during this decade, as fewer younger teachers enter the school work force.

Fig. 6. Differences in Personnel between Jewish and Arab Sectors in General and Special Primary Education.

In the second decade of this century, teacher training in Israel is in the midst of fundamental reforms. The first phase is characterized by undergraduate baccalaureate studies, coupled with practicum during studies, and one year of induction, followed by two more years of internships, during which time the novice receives guidance and support from both an experienced teacher and a group at their teaching college or university. The school principal is responsible to evaluate the novice’s work before acceptance as a permanent teacher eligible for tenure. The second phase of these reforms relates to ongoing in-service training throughout the teacher’s professional employment (Zilbershtrum, 2013). In 2009, the MoE published provisions for professional development of all teachers, including special education teachers and ancillary staff.

A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHER TRAINING

The purpose of the framework is to improve teacher quality and professionalism by developing new and attractive professional possibilities, to set more stringent acceptance criteria for teacher training, to emphasize the importance of practical experience, to enhance the relationship between theory and practice, and to set uniform required core subjects (allowing for variability and uniqueness according to each school’s educational vision). The “Ariav Committee” recommended core studies which include three main parts: content area, studies in educational foundations (pedagogy, teaching methods, research, field work, philosophical foundations, cognitive-emotional-social development, theories of teaching and learning, organization and evaluation methods, ethnic and cultural differences, and students with special needs), and compulsory studies in English, the Hebrew or Arabic, culture and citizenship, and technology skills (Ariav et al., 2006). Special education students teachers are required to master these core subjects as well as a special education specialization, either for children aged 6–21 years (usually all children with special needs and all type of placements, and in the last year students can specialize in one disability or category of disabilities) or focus on specific disabilities in preschool, elementary, or secondary school. Some of the teacher training colleges offer specific specialization in specific disabilities, such as LD, ASD, or EBD and all students in special education have one or two days of field experience each week for every year of their training. Field work includes observations, interviews with the staff, and actual teaching, with the support of both the college tutor and the staff within their class. Graduating students receive a Teaching Certificate from their college and a BEd; however, they must also be licensed (certification from MoE) after two years of successful internships. Recent data of the Central Bureau of Statistics (2010 in Ma’agan, 2013) reveals that 60% of graduated Jewish students and 67% of graduated Arab students begin their internship and more than 23% of Jewish primary teachers and 18% of Arab primary teachers leave the profession after first year of teaching (Ma’agan, 2013).

Narrative research about students’ motives for studying special education reveals that many of them choose the profession from individual motives, some have LDs themselves, others have a family member with special educational needs and have had successful life experiences (e.g., volunteering or during their compulsory military service). Often, they are motivated to improve the educational system and make it more responsive for students and most of them perceive the special education system as more significant and challenging than the general education system (Lavian, 2013). Despite their sense of idealism and a belief in their willingness and ability to work hard, special education teachers, mainly teachers in special day classes, experience professional burnout at the same levels of general education teachers; however special education teachers who work in inclusionary settings, often with small groups of students, appear to be at a lower risk for burnout (Lavian, 2012).

CONCLUSION

It appears that the DSE promulgates a comprehensive and coherent policy in accordance with special education goals and policies and is responsive to field-based needs. However, it is unclear as to what extent these plans are currently implemented (Avissar & Bav, 2010). General education teachers in Israel often do not use accommodations or modifications in their instructional methods for students with special needs, despite acknowledging their benefits and need. For example, in a study of general and special education teachers in general education settings, it was apparent that teachers did not cooperate with other professionals at school to solve problems or to share responsibility in classroom management. Special education teachers, on the other hand, reported limited yet inefficient cooperation with parents, despite official exhortations to cooperate and develop partnerships (Layser & Ben-Yehuda, 1999). Similar findings regarding this gap between the ideal and reality was found in another study of general education teachers, who rarely used instructional accommodations for students with special educational needs, despite positive attitudes and opinions regarding these accommodations (Almog & Shechtman, 2004).

NOTES

REFERENCES

Almog, O., & Shechtman, Z. (2004). Teachers’ instructional behavior towards students with special needs in regular classes and their relationship to student’s performance [in Hebrew]. Issues in Special Education and Rehabilitation, 19, 79–94.

Ariav, T., Olshtain, E., Alon, B., Back, S., Grienfeld, N., & Libman, Z. (2006). Committee for guidelines for teacher education: Report on programs in higher education institutions in Israel. Jerusalem, Israel: Council for Higher Education [in Hebrew].

Avissar, G. (2012). Inclusive education in Israel from a curriculum perspective: An exploratory study. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 27(1), 35–49.

Avissar, G., & Bav, T. (2010). [Process and trends in educational planning for students with disabilities in Israel] [in Hebrew]. Theory and Practice in Educational Planning, Ministry of Education, 21, 141–167.

Avissar, G., & Layser, Y. (2000). Evaluating values in special education as change in education [in Hebrew]. Halacha veMa’ashe b’Tichnun Limudim, 15, 97–124.

Avissar, G., Moshe, A., & Licht, P. (2013). “These are basic democratic values”: The perceptions of policy makers in the ministry of education with regard to inclusion. In and G. Avissar & S. Reiter (Eds.), Inclusiveness: From theory to practice (pp. 25–48). Haifa, Israel: AHVA Publishers.

Batsche, G., Elliot, J., Graden, J. L., Grimes, J., Kovaleski, J. F., & Prasse, D. (2005). Response to intervention: Policy considerations and implementation. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Directors of Special Education.

Bizchut. (2010). The accessibility to education in Israel – General data file [in Hebrew]. Bizchut – The Israel Human Rights Center for People with Disabilities.

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2012a). 8.29. Students with special needs in secondary education by type of disability and type of setting, 2007/08, 7. Retrieved from http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/templ_shnaton.html?num_tab = st08_29&CYear = 2012. Accessed on July 3, 2012.

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2012b). Statistical abstract of Israel 2012, selected data from the new Israel statistical abstract No. 63-2012. Jerusalem, Israel: Central Bureau of Statistics.

Comptroller’s Office. (2001). State comptroller’s annual report. Jerusalem, Israel: Government Press.

Davidovitch, M., Hemo, B., Manning-Courtney, P., & Fombonne, E. (2012). Prevalence and incidence of autism spectrum disorder in an Israeli population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(4), 1–9.

Director General – Ministry of Education. (1998, July). Individual educational program (IEP) for students in special education settings. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education and Science Press.

Director General – Ministry of Education. (2005, November). 3(A), Director General’s regulations: The core curriculum for primary education. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education and Science Press.

Director General – Ministry of Education. (2007, November). 3(d), Director General’s regulations: Inclusion plan in regular education and the treatment of children with special needs in regular education. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education and Science Press.

Director General – Ministry of Education. (2010, December). 4(A), Director General’s regulations: Matya – Local organizational resources for implementation of the special education law and expertizing Matyas of visually impaired students. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education.

Eldar, E., Talmor, R., & Wolf-Zukesrman, T. (2010). Successes and difficulties in the individual inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the eyes of their coordinators. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(1), 97–114.

Etzioni, A. (1981). Report of the national committee which examined the statues of the teacher and the teaching profession [in Hebrew]. Hed Hachinuch, 53(18), 7–17.

Fairbanks, S., Sugai, G., Guardino, D., & Lathrop, M. (2007). Response to intervention: Examining classroom behavior support in second grade. Exceptional Children, 73(3), 288–310.

Farsoun, S. K., & Zacharia, C. (1977). Palestine and the Palestinians. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93–99.

Gal, G., Abiri, L., Reichenberg, A., Gabis, L., & Gross, R. (2012). Time trends in reported autism spectrum disorders in Israel, 1986–2005. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(3), 428–431.

Gavish, B. (2002). The gap between role expectations and actual role perception for beginning teachers during their first year of teaching. Jerusalem, Israel: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Gavish, B., & Friedman, I. A. (2010). Novice teachers’ experience of teaching: A dynamic aspect of burnout. Social Psychology of Education, 13(2), 141–167.

Gumpel, T. P. (1996). Special education law in Israel. Journal of Special Education, 29(4), 457–468.

Gumpel, T. P. (2011). One step forward, two steps backward: Special education in Israel. In and M. Winzer & K. Mazuek (Eds.), International practices in special education: Debates and challenges (pp. 151–170). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press Publishers.

Gumpel, T. P., & Nir, A. E. (2005). The Israeli educational system: Blending dreams with constraints. In and K. Mazurek & M. A. Winzer (Eds.), Schooling around the world: Debates, challenges and practices (pp. 149–167). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hoffman, A., & Niderland, D. (2010). Teachers’ image in the mirror of teachers training, 1970–2006 [in Hebrew]. Dapim, 49, 43–86.

Instructions Chapter D1 for Special Education Law, 4763 [Correction number 7 for Special Education Law, 1988]. (2002).

Knesset. (2003). Center for research and information: Background document for discussion of teacher preparation in Israel and the structure of the curricula in teacher training institutions. Jerusalem, Israel: Knesset Printing Office.

Lavian, R. H. (2012). The impact of organizational climate on burnout among homeroom teachers and special education teachers (full classes/individual pupils) in mainstream schools. Teachers and Teaching, 18(2), 233–247.

Lavian, R. H. (2013). “You and I will change the world”: Student teachers’ motives for choosing special education. World Journal of Education, 3(4), 10–25.

Layser, Y., & Ben-Yehuda, S. (1999). The challenge of inclusion: Applying intervention programs by general and special education teachers [in Hebrew]. Issues in Special Education and Rehabilitation, 14(2), 17–29.

LEV-21. (2009). LEV-21 – “Towards adulthood”, curriculum for adolescents and adults between the ages of 16–21 in special education [in Hebrew]. Ministry of Education, Curriculum Division, Jerusalem, Israel.

Lipka, O. (2013). The response to intervention (RTI) model: Components and implications for teaching and learning. In and G. Avissar & S. Reiter (Eds.), Inclusiveness: From theory to practice (pp. 161–188). Haifa, Israel: AHVA Publishers.

Ma’agan, D. (2013). Reform “Ofek Chadash”: Did the reform improve the attraction of teaching profession and student achievement? [in Hebrew]. 29th annual conference, Israel Economic Committee. Retrieved from http://www.cbs.gov.il/www/presentations/educ_4_0613.pdf

Margalit, M. (1999). Report on the actualization of the abilities of students with learning disabilities. Jerusalem, Israel: Minister of Education and Science.

Marom, M., Bar-Siman Tov, K., Karon, A., & Koren, P. (2006). Inclusion of children with special needs in the regular educational system. Jerusalem: Myers – JDC – Brookdale Institute.

Meyers – JDC – Brookdale Institute. (2012, March). The Arab population in Israel: Facts and figures 2012. Jerusalem: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2011). Regulations for equal rights to people with disabilities: Individual accessibility accommodations for a student and a parent. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2012). The inclusion book: Investigating perceptions and their implementation in the inclusion process. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education, Pedagogical Administration.

Ministry of Education. (2013). Support model for the expansion of inclusion capacity and advancement of students in educational institutions. [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education – Culture and Sport. (2004). The pedagogical administration: The division of elementary schools. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education – Culture and Sport.

OECD. (2009). OECD economic surveys: Israel 2009 (Vol. 2009). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pen, R., & Tal, D. (2006). Environment designs around the principles of “quality of life” and “universal design” summons a platform of addressing any person without labeling [in Hebrew]. Eureka: Teaching Science and Technology in Primary Schools, 22, 1–6.

Raz, R., Lerner-Geva, L., Leon, O., Chodick, G., & Gabis, L. V. (2013). A survey of out-of-pocket expenditures for children with autism spectrum disorder in Israel. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2295–2302.

Reiter, S. (1999). Special needs students’ quality of life, in light of expansion the principle of normalization [in Hebrew]. Issues in Special Education and Rehabilitation, 14(2), 61–69.

Ronen, C. (1982). Introductory chapters in special education. [in Hebrew]. Tel Aviv: Otsar Hamore.

Sachs, S., Levian, M., & Weiszkopf, N. (1992). Introduction to special education. [in Hebrew] (Vol. Unit 1). Tel Aviv, Israel: Open University.

Sadeh, S. (2003). Special education in Israel: Pre-state period. Historical documentation of special education. [in Hebrew]. Tel Aviv, Israel: Special Education Division, Ministry of Education.

Schalock, R. L., Brown, I., Brown, R., Cummins, R. A., Felce, D., Matikka, L. … Parmenter, T. (2002). Conceptualization, measurement, and application of quality of life for persons with intellectual disabilities: Report of an international panel of experts. Mental Retardation, 40(6), 457–470.

Shabat, Y. (2011). An assisting technology – For what? [in Hebrew]. Field of Vision (“Sde Reiya”), 3, 2–4.

Shmueli, E. (2003). Forming factors of educational policy in Israel. Studies in Educational Administration and Organization, 27, 7–36.

Special Education Law of 4758, Knesset. (1988).

Tal, D., & Leshem, D. (2007). Curriculum for students with special needs. Jerusalem, Israel: The Division of Special Education, Ministry of Education.

Tseva, Y. (Ed.). (2012). A review of public services. [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem: Ministry of Social Affairs and Social Services.

Wargen, Y. (2006). Education in East Jerusalem (p. 15). Jerusalem: Knesset Center for Research and Information.

Ya’acov, S. (2012). Training teachers in Israel: Who needs the retraining plan? [in Hebrew]. Kav HaHinuch, 586, 1–3.

Zachor, D. A., & Ben-Itzchak, E. (2010). Treatment approach, autism severity and intervention outcomes in young children. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(3), 425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.10.013

Zachor, D. A., Ben-Itzchak, E., Rabinovich, A.-L., & Lahat, E. (2007). Change in autism core symptoms with intervention. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(4), 304–317. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2006.12.001

Zilbershtrum, S. (2013). The policy of the division of internship and teaching entry [in Hebrew]. In and S. Shimoni & A. Avinadav-Unger (Eds.), The sequence: Training, specialization and professional development of teachers – Policy, theory and practice (pp. 95–100). Tel Aviv: Mofet.

Zionit, Y., & Ben-Arie, A. (2012). 2012 [Children in Israel, 2012]. [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel National Council for the Child.

Zionit, Y., Berman, T., & Ben-Arie, A. (2009). 2009 [Children in Israel 2009]. [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel National Council for the Child.