SPECIAL EDUCATION TODAY IN THE KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA

Turki A. Alquraini

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a comprehensive view of special education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The chapter starts with the origins and attitudes of the Saudi citizens regarding persons with special needs. Next the chapter examines trends in legislation and litigation pertaining to persons who are disabled which led to the government’s passage of Regulations of Special Education Programs and Institutes (RSEPI) in 2001. The RSEPI regulations were modeled after the United States 1997 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Included in the discussion of the RSEPI is a delineation of the Disability Code which is comprised of 16 articles. The author also provides information on prominent educational intervention employed in the Kingdom as well details about the preparation of paraprofessionals and special education teachers. The chapter concludes with the special education progress that has occurred since the passage of RSEPI.

INTRODUCTION

Special education today in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has been significantly influenced by a number of factors that include its religious and cultural differences of its citizens as well as its recent formation as a country. KSA is located in the southwest of the Arabian Peninsula. This country is partially bordered in the east by Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, and in the north by Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait (Alquraini, 2010). King Abdul-Aziz al Saud and a small group of men established this country in 1932. After this date, the Saudi government considered the improvement of several fields, including healthcare, the economy, and the education system. As part of its educational system improvement, KSA established the Ministry of Education which regulates the free education services for all Saudi students. Right now, there are 26,934 schools that serve almost 5 million students (boys and girls) from kindergarten to the high school level with almost a half-million teachers (men and women) (Ministry of Education, 2012). This Ministry of Education has to take into consideration the KSA religious and cultural aspects in the education of the Saudi students; therefore, there are separate boys’ and girls’ schools. This ministry is also responsible for establishing education building codes and architectural requirements, certifying and hiring teachers, setting standards for teacher degrees, providing workshops and in-services training for teachers, and developing the general curriculum (Alquraini, 2010). Additionally, this ministry provides special education services for students with disabilities, especially those who have mild to moderate disabilities from the ages of 6 to 18 years. In the following sections, readers will be provided with a more comprehensive and detailed information to understand special education today in Saudi Arabia after its recent formation as a country. It includes the following sections: origins and attitudes, prevalence and incident rates, trends in legislation and litigation, prominent education interventions, preparation for special education personnel, and the overall progress that KSA has made in establishing inclusive special education services.

ORIGINS AND ATTITUDES

In KSA, there are religious and cultural aspects that differentiate it dramatically at times from Western countries and contexts. For instance, Saudi society values are inherently affected by the Islamic religion, which is based on the Qur’an and the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad. These long established society values, in some cases, view disability as punishment for a person because he or she or his or her family has done something wrong in the form of a “sin” toward Allah (God) or another individual in society. This value may lead to derision and ridicule of a person/family that has a child with a disability. Another view toward disability, according to Saudi values, is that having a child with a disability serves as a test from Allah for either the person or his or her family to see if they will be patient in order to enter Paradise, the holy place prepared by Allah for those who follow the rules of the Qur’an and the Sunnah. This view toward disability in KSA leads most Saudi citizens to believe that individuals with disabilities are dependent on other people, are entrenched in a low quality of life, and are helpless (Al-Gain & Al-Abddulwahab, 2002). Unfortunately, this latter view can cause Saudi citizens to consider people with disabilities as objects of ridicule and may prevent and exclude them from participating in any type of typical community or social activity. The effect of holding these values and views leads to different attitudes toward people with disabilities which can have an effect on their education and treatment. Some of these attitudes are discussed later.

Several studies have examined the attitudes toward people with disabilities in KSA. For example, Al-Abdulwahab and Al-Gain (2003) examined the attitudes of 130 healthcare professionals regarding people with physical disabilities. Their research pointed out that the majority of healthcare professionals had positive attitudes toward people with physical disability. From this finding, the researchers postulated that the values of Saudi culture apparently had little effect on healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward people with physical disabilities. Another attitude investigation about people with physical disabilities was carried out by Al-Demadi and Al-Shinawi (1989), who examined the attitudes of 458 college students with different undergraduate majors at King Saud University toward people with physical disabilities. The authors investigated the attitudes of the students based on three independent variables: gender, educational level, and major. The researchers found that students with a special education major had more positive attitudes than other students in other college majors. Further, it was reported that there were no differences in the attitudes among sophomores, juniors, and seniors toward people with physical disabilities, and that male students had more positive attitudes toward individuals with physical disabilities than females.

Another study was conducted by Al-Muslat (1987), who examined the attitudes of 420 teachers, 115 principals, and 52 supervisors toward people with disabilities, including people with visual impairments, hearing impairments, emotional and behavior disorders, intellectual impairments, and learning disorders. Al-Muslat indicated that the teachers, principals, and supervisors in Saudi Arabia exhibited negative attitudes toward people with emotional and behavior disorders and intellectual impairments but positive attitudes toward people with learning disorders, visual impairments, and hearing impairments.

Another interesting attitude study was carried out by Al-Sartawi (1987), who investigated the attitudes of 252 college students at the College of Education at King Saud University toward people with intellectual impairments. The investigator examined the students attitudes based on college major, level of education, and grade point average (GPA). Al-Sartawi reported that students who majored in special education or physiology had more positive attitudes toward people with intellectual impairments than students who had other college majors. This researcher also indicated that junior students had more positive attitudes than did students in other levels of education. Lastly, the researcher found that the college students with the highest GPAs expressed more positive attitudes toward individuals with intellectual impairments than those students with lower GPAs.

A more inclusive study on attitudes was carried out by Sadek, Mousa, and Sesalem (1986) who explored the attitudes of Saudi citizens toward people with visual impairments. The researchers examined attitudes by age, education level, and gender. The researchers indicated that citizens had positive attitudes toward people with visual impairments, and that there was no difference in their attitudes based on their age or level of education. However, female citizens expressed less positive attitudes than male citizens toward people with visual impairments.

Lastly, another inclusive study was carried out by Al-Marsouqi (1980) who investigated the attitudes of Saudi citizens toward people with hearing impairment, visual impairment, and intellectual impairments. The researcher analyzed citizen’s attitudes based on both demographic and independent variables that included gender, contact with individuals with disability, and level of education. This study revealed that Saudi citizens had positive attitudes toward people with hearing impairment and visual impairment; however, they had negative attitudes toward people with intellectual impairments. Additionally, those citizens who had experiences with people with disabilities expressed more positive attitudes than citizens who did not. In contrast from the findings above, female citizens were found to have more positive attitudes toward people with disabilities than male citizens.

The above studies indicate that a variety of variables affect attitudes of Saudi healthcare providers, college students, teachers, principals, school supervisors, and citizens toward people with disabilities. Variables such as college major, gender, age, prior experience, education level, and the specific disability can influence one’s attitudes. While long standing KSA cultural and religious differences may have a negative effect on a Saudi citizen’s view of an individual with a disability, there is more recent special education literature evidence that reports that many Saudi citizens have a positive view of people with disabilities. Such evidence is an indication that Saudi citizens are becoming more willing to accept individuals whose abilities differ from theirs and participate with them in different life activities.

This growing acceptance and engagement in KSA can be traced historically to the early efforts of families to gain support for special education considerations for their children in the 1950s and 1960s. For example, prior to 1958, most students with disabilities in KSA did not obtain any type of special education services or related services. The majority of these students were supported by their families, who struggled in order to obtain healthcare and other assistance for their children (Al-Ajmi, 2006). In 1954, a few Saudi citizens with visual impairments started to learn the Braille method from someone who came back from Iraq at that time (Al-Mousa, 2008). After that, this group tried to teach this method to more students with visual impairments in schools as well as colleges. Within a short period of time, their efforts paid off in 1959 and 1960, when the Ministry of Education established the first institute for 40 students with visual impairments (Al-Mousa, 2008).

A few years later in 1962, the Ministry of Education established a special education department to serve three categories of students: those with visual, hearing, and intellectual disabilities. The Ministry of Education then established institutes for these three categories across the country where special curriculums were used to educate these students. Students could attend these institutes when they reached public school age. However, in 1997, the philosophy of this special education department changed, which dramatically affected the special education services for students with disabilities. For example, the department started to consider early assessment for students at-risk so that those students with identified disabilities could be provided early remedial intervention. This department also extended its services to include many other types of students with disabilities, such as students with physical, learning, and multiple disabilities, and autism (Al-Mousa, 2008).

With these changes, it became apparent to the Saudi government that there was a lack of appropriate and best practice special education services for students with disabilities. As a means to remedy this situation, the Saudi government made a significant effort to improvement these services. The government requested that personnel from the Special Education Department under the Ministry of Education and some special education faculty at King Saud University, who earned their doctoral degrees from the United States, review the United States’ special education policies, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 1997) in the hope of developing a more appropriate special education policy for KSA. Their efforts resulted in the 2001 Regulations of Special Education Programs and Institutes (RSEPI) which introduced the first special education regulations for students with disabilities in KSA (Alquraini, 2013).

The RSEPI identified 10 categories of disability that should be served by the schools: hearing disabilities, visual disabilities, intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities (LD), gifted and talented abilities, autism, multiple disabilities, physical and health impairment, communication disorders, and emotional and behavioral disorders. These categories were based on commonly used special education terms among special education professionals across the globe and the prevailing best practice special education literature.

The RSEPI specifies that students identified as having one of these categories must be assessed by a multidisciplinary team which is housed in each school. Once a student is identified with a disability, he/she will be provided the necessary special education services. This team usually uses formal tools to assess the child with a presumed disability, such as intelligence quotient scales (e.g., Wechsler Intelligence Scales), adaptive behavior scales (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior), and achievement tests (Wechsler Individual Achievement Test). This team might also use other informal scales, such as interviews or observation. Even though this effort to provide appropriate special education services for those students has improved the practice of special education in KSA immensely, these services are still similar to those that were provided in the 1970s in the United States such as the mainstreaming philosophy, self-contained classrooms, resource room placement, placement of students into a classroom by their identified categorical classification (learning disabled, behaviorally and emotionally disordered, intellectual impaired), and the establishment of special schools and centers for children with a specific type of disability (center for the physically impaired).

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENT RATES

According to the Central Department of Statistics and Information Population and Vital Statistics (2011) in KSA, 0.8% of the Saudi population is reported as having disabilities (approximately 17,493,364 people). Also, the number of KSA children born annually with a disability is between 400 and 500. Additionally, the number of people with disabilities by age as reported by this center is as follows: 1% younger than 1 year, 3% from 1 to 4 years, and 4% from age 5 to 80 years and above. The percentage of KSA people with disabilities by gender is 65% males and 35% females. This center reported the number of people with disabilities in KSA by type of disability as follows: 9,522 people with visual impairment, 29,507 people with intellectual disabilities, 21,462 people with multiple disabilities, 5,306 people with psychological disorders, 5,773 people with hearing impairment, 7,067 people with communication disorders, and 44,456 people with physical disabilities. Finally, there are two main factors that might cause disability in KSA: genetic causes associated with consanguinity, and a high rate of car accidents (Al-Gain & Al-Abddulwahab, 2002).

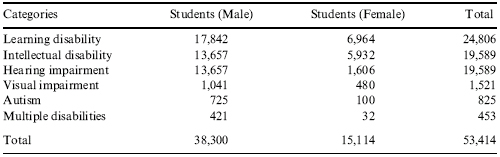

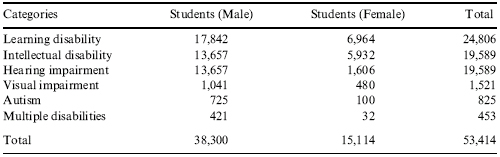

In the community of Saudi schools, there are different prevalence and incident rates of disability. The Ministry of Education has reported that 53,414 disabled students (see Table 1), including those with intellectual disability, deaf and hard of hearing impairment, learning disability, autism, multiple disabilities, and visual impairment, receive special education services in public schools or institutes. Today, 24,806 students (17,842 male and 6,964 female) out of the entire public school-age population between the ages of 6 and 18 years have been identified as having a learning disability. Students classified with a learning disability therefore represent about 46% of the entire school-age disability population. Another major category is students with intellectual disabilities. Today 19,589 students (13,657 male and 5,932 female) receive special education services due to their intellectual impairment. This number represents about 36% of the entire public school-age disability population. Students classified with hearing impairment or as hard of hearing represent approximately 13%, or a total of 6,219 (4,613 male and 1,606 female) students out of the entire school-age disability population. Additionally, 3% (1,521 students: 1,041 male and 480 female) of the entire school-age disability population is considered visually impaired. Students with autism represent 2% of the public school-age disability population with a total of 825 students (725 male and 100 female). Finally, a total of 453 students (421 male and 32 female) with multiple disabilities represent only 1% of the public school-age disability population. Even though these reported numbers are meant to represent the percentage of students with disabilities, special education professionals in KSA question whether these numbers accurately represent the total number of students with disabilities given that the total public school population is 4,904,777 students. Unfortunately, this question cannot be answered for now, since KSA does not have a national study regarding the prevalence and incident rates for all categories of disability at the school-age level.

Table 1. The Categories and Number of Students with Disabilities Who Are Serviced by Special Education in Public Schools in KSA.

Additionally, there are some reasons that might affect conducting accurate research regarding the disability issues in Saudi Arabia, including “incidence of consanguineous marriage, the high incidence of car accidents, and the fact that some families feel ashamed about having a child with a disability, as a result, they tend to avoid participation in such research” (Al-Gain & Al-Abddulwahab, 2002, p. 2).

TRENDS IN LEGISLATION AND LITIGATION

Since the early 1990s, the Ministry of Education has considered how to improve the special education services for students with disabilities by establishing rules that protect the rights of these students. In 2001, the Special Education Department in the Ministry of Education established the RSEPI, after extensive collaboration with other agencies, such as the Special Education Department at King Saud University, as well as taking into consideration the US special education policies, including IDEA (1997) and Alquraini (2013). In essence, the RSEPI is modeled after the US’s IDEA and its major elements are delineated below.

Major Elements of the RSEPI

The RSEPI includes 11 parts that present critical education provisions to adequately serve special education students and their families (Ministry of Education, 2002). Part One delineates the important definitions used in this legislation so that teachers, administrators, supervisors, parts, mental health professionals, and other service providers can easily communicate essential aspects to one another. For instance, it defines the concepts of “disability,” “least restrictive environment,” “transition services,” “multidisciplinary team,” “IEPs,” “special education teacher,” “resource room,” and other aspects of providing education services to special education students (Alquraini, 2013).

In Part Two, the primary goals of special education services are presented. For example, these services should be provided for students with disabilities to meet their unique needs and support them in obtaining the necessary skills that will assist them in living independently and integrating appropriately into society. These goals can be achieved through different procedures such as: (a) determining the needs of students with disabilities through early detection process; (b) providing a free and appropriate special education and related services that meet their needs; (c) specifying these services to the students with disabilities within their IEPs; (d) taking advantage of scientific research to improve the services of special education; and (e) raising awareness about the disability among the members of society by discussing the causes of the disability and the ways to reduce it (Alquraini, 2013).

Part Three presents the foundations of special education in KSA in 28 subsections that discuss important concepts concerning the rights of students with disabilities to acquire appropriate education. This part emphasizes that students with disabilities should be educated in general education and that IEP teams should make decisions regarding the placement of students with disabilities, taking into consideration a continuum of alternative placements.

Furthermore, in Part Four, the characteristics of the 10 categories of disabilities discussed previously (hearing impairment, visual impairment, intellectual disabilities, LD, gifted and talented abilities, autism, multiple disabilities, physical and health impairment, communication disorders, and emotional and behavioral disorders) are explained. Also, it defines the procedures of the assessment for each disability in each category (Alquraini, 2013).

Part Five presents the transition services available for students with disabilities in KSA. It indicates that the main goal of transition services is assisting these students to prepare in moving from one environment to another. Further, this part emphasizes that transition services should be provided for the student when he or she needs them as part of his or her IEPs. Additionally, it defines the types of transition services that might be provided, such as those that assist these students in moving across different levels of education (e.g., preschool to elementary). Finally, Part Five emphasizes that the transition services should be provided for the students with disabilities at an early stage (Alquraini, 2013).

Part Six describes in a comprehensive manner the tasks and responsibilities for professionals (e.g., teachers, principals, and service providers) who work with students with disabilities, either in public schools or special schools. The responsibilities of the agencies for the school districts and the schools regarding these students and their families are determined in Part Seven of the RSEPI. This is a critical aspect because these agencies are responsible for providing a free and appropriate education for students with disabilities. In addition, these agencies must provide awareness programs for the families of these students that will increase their knowledge regarding different issues accompanying disability. Lastly, these agencies are to encourage these families to be involved in different activities, such as participating in short- and long-term planning and providing IEPs for their children (Alquraini, 2013).

Part Eight includes specific procedures of assessment and evaluation for students to determine if they are eligible for special education services. For example, this part indicates the definition, goals, and procedures associated with assessment and the composition of the multidisciplinary team (e.g., the special education teacher, general education teacher, parents, and others). It defines the steps of assessment that should be considered by the schools to determine the eligibility for special education services: (a) obtaining consent from the parents before diagnosis of the child; (b) gathering preliminary information on the status of the child who might need special education services; (c) referral of the child for further assessment procedures if needed; (d) and assessment of the child’s needs in different areas by the multidisciplinary team (Alquraini, 2013).

Part Nine delineates the individual education program (IEP) that should be provided for each student who is eligible for special education services. This part defines the importance of the IEP for students with a disability and specifies that the IEP is a unique approach that should be considered to meet the individual curriculum needs of each student and appropriate special education and related services which must be incorporated into the student’s school day. Further, it explains the essential considerations of the IEP such as the requirement that it be jointly developed by the multidisciplinary team and the student’s family; aspects that should be included in the IEP (general information about the student, the current performance of the student, special education and related services that the student might need, the professionals who are participating in its delivery). Finally, this part mandates that the student must participate in the IEP and the requirement that the IEP should be evaluated annually to determine whether or not its goals have been met (Alquraini, 2013).

The evaluation process for students with disabilities is explained in Part Ten. It describes the definition and goal of the evaluation process (e.g., to determine the current performance of the student). In addition, Part Ten defines significant aspects that should be considered by the multidisciplinary team such as appropriate assessment devises and tests for evaluating each type of disability (e.g., when evaluating a student with possible intellectual impairment, the multiple disciplinary team should consider three assessment devises to measure the student’s current intellectual, adaptive functioning, and academic level). Lastly, Part Eleven explains general rules for schools and school districts, such as the fact that only the Special Education Department is responsible for the interpretation of the RSEPI (Alquraini, 2013).

Disability Code

The Disability Code was passed by the Saudi government in 2000. It includes 16 articles that present different issues regarding disability. For instance, Article One of this legislation describes the term of disability as described by the Prince Salman Center for Disability Research (2004), namely,

A person with a disability is one who is totally or partially disabled with respect to his/her bodily, material, mental, communicative, academic or psychological capabilities, to the extent that it compromises the ability of that person to meet his/her normal needs as compared to his/her non-disabled counterparts. (p. 5)

Based on Article One, a student with a special need could be eligible under one of nine categories of disability, namely: visual disability, hearing disability, cognitive disability, physical disability, LD, speech and language impairments, behavioral problems, developmental delay, and multiple disabilities (Prince Salman Center for Disability Research, 2004). A provision of this article further requires government and private agencies to assist eligible people under the Disability Code in welfare, habilitation, health, education, training and rehabilitation, employment, complementary services, and other areas (Prince Salman Center for Disability Research, 2004).

Article Two of the Disability Code specifies that people with disabilities should have access to free and appropriate services in the areas of health, education, training and habilitation services, employment, social programs, and public services through public or governmental agencies. More specifically, it defines the main issues that should be considered by services providers in these areas. For instance, in the health area, this legislation requires service providers in the healthcare field to provide medical as well as habilitation services in the early stages of disability for both the person with a disability and his or her family and to improve the healthcare for people with disabilities while taking into consideration the current approach to healthcare; health service providers (e.g., nurses) are also expected to have an adequate level of training to be able to provide high quality health-care services for people with disabilities (Prince Salman Center for Disability Research, 2004).

Specific to the education area, the Disability Code requires a free and appropriate education for all people with disabilities regardless of their educational stage (e.g., preschool, general, vocational, and higher education). Under the Disability Code, training and habilitation services should be provided by vocational and social habilitation centers for individuals with disabilities in KSA as required by the labor law (Prince Salman Center for Disability Research, 2004).

In the employment area, this legislation indicates that people with disabilities have the right to get jobs that might assist them in discovering their personal capabilities and allow them to earn income just like other individuals in society. It also requires all agencies either governmental or private that have 25 employees or more to employ 4% of their workforce from categories of people with disabilities and give them equal job growth opportunity in the employment environment similar to those of nondisabled workers (Prince Salman Center for Disability Research, 2004).

The Disability Code also emphasizes that people with disabilities should participate in all of the social programs that guarantee them the right and opportunity to fully integrate with other people in society without discrimination based on their disabilities. Also, it requires that public services should be facilitated and accessible for all people with disabilities in terms of public transportations, technology, and other services. Finally, under this legislation most people with disabilities can get benefits, such as:

- Persons with disabilities get 50% off of their tickets through all public transportation.

- Persons with disabilities are provided all types of care, including treatment and medicines free of charge.

- Persons will disabilities are provided job support on an equal basis as other people without disabilities.

- Persons will disabilities are provided parking spaces for their cars.

- Persons with disabilities, as well as their families, are provided with financial assistance.

These legislations, particularly Disability Code legislation, guarantee the right for all people with disabilities to receive free and appropriate services in terms of health, education, training and habilitation services, employment, social programs, and public services. They also work to protect against any type of discrimination.

To summarize, the RSEPI and the Disability Code support the right of children with disabilities to obtain a free and appropriate education by considering many issues that guarantee this right. The RSEPI requires schools to educate their students with disabilities in a general education setting to the maximum extent, taking into account a continuum of alternative placements. Further, the RSEPI requires that special education services (e.g., IEPs, related services, transition services, and others) should be carried out with students with disabilities in the real world to discourage isolation and segregation while increasing opportunities for acceptance and tolerance by other nondisabled citizens (Alquraini, 2013).

PROMINENT EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION

The KSA special education services and intervention are in a developing and formative stage, similar to the commencement of special education policies and practices that were initiated in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s (Marza, 2002). Due to their current stage of development, provisions and best practices of appropriate education for students with disabilities are lacking in the following areas.

Education Setting

Even though the RSEPI requires schools to allow students with disabilities, including students with moderate and severe disabilities, to receive their education with typically developing peers in regular classrooms to the maximum extent of their abilities, this has not been practiced with students with disabilities in KSA. In other words, students with disabilities still receive their education separately in special schools, private institutions, and self-contained classrooms within the school. Positively, students with LD are educated in general education classrooms with their typically developing peers, with some support from special education services such as resource rooms (Al-Ahmadi, 2009; Al-Mousa, Al-Sartawi, Al-Adbuljabar, Al-Batal, & Al-Husain, 2006). LD students follow the general education curriculum. Meanwhile, students with intellectual disabilities receive their education in self-contained classrooms within public schools, sharing some non-curricular activities with their typically developing peers (Al-Mousa et al., 2006). These students follow the special education curriculum designed by the Ministry of Education, which is different than the general curriculum that is provided to their typically developing peers. Students with autism, multiple disabilities, and visual and hearing impairments are educated in special schools which does not allow to them to interact with their typically developing peers.

Procedures to Determine Eligibility for Special Education Services

Unfortunately, in KSA the diagnosis and assessment processes to determine the eligibility of students for special education and related services are still not free of shortcomings. First off, the assessment process for children does not begin early enough to successfully determine disabilities. This process usually starts when the child goes to school, so the schools and other agencies do not provide early intervention for preschool children with disabilities and their families (Alquraini, 2010). Additionally, most of the special education institutes, as well as public schools, lack a multidisciplinary team and reliable and valid assessment scales to carry out intellectual, adaptive, achievement, and behavioral evaluations that are appropriate for the cultural standards of KSA (Al-Nahdi, 2007). Lacking an appropriate multidisciplinary team, assessment procedures for children with mild to moderate disabilities are non-team based. Therefore, in most cases, the schools’ psychologists define students’ eligibility for special education service based on a student’s IQ scores and teacher observation. In time, the overall assessment and diagnostic procedures will be reassessed and revised to achieve a truly reflective practice in KSA but for now misdiagnosis and inappropriate diagnosis may occur.

Providing Individual Education Programs

The RSEPI requires schools to provide an IEP for each student with a disability and it has become one of the most important educational services provided for each child. However, little historical research has examined IEPs for students with disabilities in Saudi Arabia but recently researchers (Al-Herz, 2008) have begun to shed light on this vital provision of the law. For example, Al-Herz (2008) examined achievement of IEP goals and related difficulties in programs and special education institutes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This researcher found that special education teachers successfully determine the important elements of IEPs in terms of the student’s weaknesses and strengths, annual goals and short-term objectives, and needs requiring specially designed instruction. However, this study concluded that some obstacles impede the provision of effective and appropriate IEPs, such as the lack of efficient multidisciplinary teams members (including the special education teacher, the child’s previous teachers, the parents of the child, and other members as needed) to formulate short- and long-term IEP goals. Also, the study indicated that the IEPs did not address the student’s needs based on their current individual strengths and weaknesses (Al-Herz, 2008). Lastly, Al-Herz pointed out those families in the study did not participate effectively with other school staff in determining the needs of their children, or in the preparation and implementation of IEPs.

The above study points out significant deficit issues regarding the provision of establishing appropriate individual education programs. Not having team members establish a student’s IEP based upon their current strengths and weaknesses is problematic because many times IEPs and short- and long-term goals are written by special education teachers without participation of the parents and other service providers (Al-Herz, 2008). This leads to the classroom special education teacher being solely responsible for IEPs for up to 15 students with disabilities in the class. Unfortunately, this situation makes it difficult for the teacher to pay individual attention to each student needs. To summarize, although students with mild to moderate disabilities have received appropriate education, more effort is needed to truly individualize the services received.

Related Services for Students with Disabilities

The RSEPI states that in order for students with special education needs to receive maximum benefit from their special educational programs, related services such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech–language, and counseling services must be provided (Ministry of Education, 2002). A number of researchers (Al-Otaibi & Al-Sartawi, 2009; Alquraini, 2007; Al-Sartawi & Grageah, 2010; Al-Wabli, 1996; Hanafi, 2008) have examined the feasibility of related services and their importance for students with disabilities in special education institutes or centers and public schools. For instance, Al-Wabli (1996) examined the feasibility of related services and their importance in special institutes for students with intellectual disabilities. This researcher found that speech–language pathologists, school counselors, psychologists, and social workers were available in these special institutes examined but occupational therapy and physical therapy services were lacking at times.

Following the above line of investigation, Alquraini (2007) examined the feasibility and effectiveness of related services for students with intellectual disabilities in public schools. According to this researcher, the most readily available related services were transportation, speech and language therapy, psychological services, school counseling, and school health services. On the other hand, social work service, occupational, and physical therapy services were available infrequently for these students. A similar study was conducted by Hanafi (2008), who examined the viability of related services for students with hearing disabilities in public schools. The researcher indicated that health and medical services were more available for these students; however, social worker and rehabilitation services were not available. Al-Otaibi and Al-Sartawi (2009) investigated the feasibility of related services for students with multiple disabilities in special education centers and institutes. The researchers reported that the special education centers and institutes lacked health, medical, and physical therapy services. Finally, Al-Sartawi and Grageah (2010) examined the feasibility of related services for students with autism in special education centers. These researchers concluded that there were shortcomings in the provision of related services for students with autism in terms of speech and language therapy, psychological, school counseling, and social worker services.

In summary, although KSA students with a variety of disabilities, who attend public schools or special education centers and institutes, receive some related services other services that they need are unavailable. This is likely due to a lack of professionals who specialize in these fields, or because professionals with these foci (e.g., physical and occupational therapy) are often employed in hospitals instead of schools due where they receive greater salaries (Alquraini, 2007). That being said, there are some private agencies such as Sultan Bin Abdulaziz Humanitarian City that do provide these services. Unfortunately, parents must pay for these services, since the RSEPI does not require schools or schools districts to pay for private agencies to provide these services. In conclusion, students with disabilities in KSA public schools, special education centers and institutes receive some related services but for those students that need a professional with a specific focus (e.g., physical therapy) their special needs go unmeet.

Transition Services

The RSEPI requires that transition services be provided for students with disabilities. According to the RSEPI, transition services are intended to prepare the student with disabilities to move from one environment or stage to another (Ministry of Education, 2002). Additionally, this legislation emphasizes that transition services should be provided for the student when he or she needs them as part of his/her IEP. The RSEPI defines the types of transition services that may be provided in order to assist students to move to different levels of education (e.g., preschool to elementary, high school to higher education, or employment settings) (Ministry of Education, 2002). Finally, the RSEPI indicates that transition services should be provided for students with disabilities at an early stage without defining that age. For instance, it states that when the student is 16 years or younger, he or she should receive transition services when necessary. Despite this fact, transition services have not always been completely carried out for students with disabilities (Almuaqel, 2006). This was demonstrated by Almuaqel (2006) in a study which examined the perceptions of parents, special education teachers, and rehabilitation counselors for students with intellectual delays regarding these students’ individualized transitional plans. Finally, even though transition services are mandated by the RSEPI, to the best of this researcher’s knowledge, there is no published research addressing transition services for students with disabilities in KSA.

PREPARATION OF SPECIAL EDUCATION PERSONNEL

Paraprofessionals

In KSA, the public schools lack paraprofessionals who can be supportive of both teachers and students in different ways (e.g., that assist the teachers in adapting and modifying curricular activities). It is becoming critical that the Ministry of Education consider ways to increase the number of paraprofessionals that can be trained and hired to assist public school teachers and students with disabilities. This author recommends that this can be accomplished by employing people who have at least a high school diploma and have passed a specific test that determines whether they are qualified for the job. Once they are qualified for the role of a paraprofessional, they can be trained via in-service workshops regarding the specific roles that need to be carried out. This training would then be followed up with on the job training and supervision.

Teacher Preparation

In KSA, there are 24 university special education departments that prepare special education teachers based on a category (e.g., learning disabled, hearing impaired) of students that they will work with. Some of these departments prepare their teachers to work with three main categories of disability (intellectual disability, learning disability, and hearing impartment). Other departments prepare their teachers to work with students with autism, communication disorders, and behavioral disorders. There is only one university department that prepares teachers to work with students with multiple disabilities and provide early intervention for children with disabilities. Most of the university departments have general programs in special education that provide general special education coursework (e.g., educating students with disabilities in public schools, inclusive education, introduction of special education, etc.) and a special program that focuses on specific disabilities such as intellectual disabilities (e.g., teaching methods for students with intellectual disabilities, an introduction to intellectual disability). There is only one special education department at King Saud University that has been accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). All college students in teacher training programs complete three and a half years of coursework and a practicum of one semester. After successfully completing the above requirements, the students participate in day-to-day teaching of students with disabilities in self-continued classes, institutes, or a resource room. After successfully completing their day-to-day training, they become certified as a special education teacher and can seek employment as a special education teacher. Special education teachers are encouraged to get a graduate degree at one of four university special education departments that provide a master’s degree in special education based on a category of disability.

PROGRESS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION SERVICES IN SAUDI ARABIA

Despite the problematic issues addressed above regarding special education services in KSA, the services have improved. This improvement has occurred in educating students with mild and moderate disabilities in the least restrictive environment, such as general classrooms or self-contained classrooms in public schools, with some opportunities to participate with their typically developing peers in nonacademic activities. An emerging agenda is to improve the education of students with moderate to severe disabilities, including those with autism and multiple disabilities. Also there has been more interest in the past few years in adding students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and emotional and behavioral disorders to meet their special needs. Financial and governmental support will be sought to increase the number of professionals who can participate in related, transition, vocational, and multidisciplinary team services. It is obvious that individuals with disabilities who acquire maximum benefit from their special educational programs will be better prepared to transfer from their school environment to a community environment and be less dependent on others on a daily life long basis.

Even though, there are 24 university special education departments that prepare special education teachers in KSA, these departments do not always provide the best knowledge base and teaching technique skills required to assist the teachers to work in inclusive classrooms, to provide effective transition services, and to use assistive technologies. Therefore, it is recommended that these department curriculums be revised and reoriented so that general and special education teachers are taught to work together in a collaborate manner to educate students with disabilities who are placed in an inclusive classroom. This reoriented curriculum can be enhanced by classroom teachers’ use of available assistive technology.

The RSEPI and public school programs for students with LD highlight the right for people with disabilities to obtain free appropriate education services as well as other services such as: healthcare, training and habilitation, employment development, and social programs. However, in the real world, these rights have not been fully granted to individuals with disabilities in KSA. Today in KSA, there are different types of discrimination that people with disabilities still face related to accessing education, employment, and social services. Additionally, females with disabilities are still suffering from discrimination based on gender bias and prejudice similar to nondisabled females. The following section discusses the above issues in more detail and makes appropriate recommendations and suggestions that policymakers, educators, and other professionals might consider to improve the quality of life and promote equal rights for individuals with disabilities in the Saudi society.

Although the code of disability legislation underlined the rights of individuals with disabilities, these individuals still struggle with some issues regarding employment in terms of their hours worked, workplace safety and security, and negative attitudes from employers toward hiring people with disabilities. The Ministry of Labor is now trying to solve these issues by creating laws that protect the rights of these individuals in getting appropriate jobs and fair work conditions.

As KSA continues its dramatic period of improvement, changes in special education services will occur rapidly (Al-Quraini, 2012). The following suggestions might be considered to improve special education services in KSA. First, policymakers should review existing legislation related to students with disabilities and evaluate each laws’ relevance to worldwide current trends in providing best practice special education services. This review should take into consideration successful policy experiences such as IDEA (1997) in the United States. More specifically the review should evaluate major tenets for providing a free appropriate education for individuals with special needs in terms of the following:

(A) Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): This term should be clarified in the RSEPI to mean that the appropriate place to educate students with disabilities is in a general education setting to the maximum extent possible; however, when the level or severity of disability does not allow for the student to be the placed in this setting, the continuum of alternative placement options should be considered, including the general classroom, the special education classroom, special schools, home instruction, or instruction in hospitals and institutions.

(B) Procedural Safeguards: Under this regulation, an amendment to the RSEPI should be made for identifying procedures (procedural safeguards) that guarantee the rights of parents or guardians of children with severe disabilities regarding settling education disputes. This part should outline procedures that assist students with disabilities to be educated using special education services. For example, parents or guardians should receive a written letter that informs them about any procedures that might be conducted by the schools with their children regarding educational placement. This letter should be sent by the school to the parents with sufficient notice (Yell, 2006). This letter also ought to explain clearly the description of the action, reasons for this action, and the further procedures that might be conducted with the student.

RSEPI must also mandate that the parent has the right to discuss any educational placement pertaining to their child made by the school that requires further procedures. There are some times when parents disagree with the decision made by the schools about educational placement. Therefore, another agency should be involved in solving this disagreement. For instance, the school districts might establish an office of hearing in each school district that aims to facilitate a problem between the schools or service providers and the parents (Yell, 2006).

Additionally, when the parents of the student cannot solve the dilemma with the school or school district, further procedures might be considered in terms of taking the issue to the local court in each city or the Supreme Court (the highest level of court in KSA). The final decisions of the courts should be reported and published in a specific database that might assist policymakers and researchers in developing special education policy regarding placement in the general education setting for students with severe disabilities in KSA.

(C) Responsibility for Implementation: A regulation that should be considered in the amendment to the RSEPI is the name of the agency or department that has responsibility for the implementation of this legislation. This part should also identify responsibility to enforce the implementation of the RSEPI. For example, the Special Education Department should have the power and responsibility to monitor and enforce special education services, particularly educating students with disabilities in the LRE under this legislation.

(D) Developing an Effective System of Accountability: The main reason behind many of the problems with the implementation of the RSEPI in Saudi Arabia is a system accountability absence to enforce the requirements of this legislation in the real world. Therefore, it is highly recommended that an effective monitoring system needs to be put in place to assist the Special Education Department in Saudi Arabia in investigating whether the requirements of the RSEPI have been carried out for students with disabilities, particularly educating students with disabilities in the LRE.

The main goals of this system would be enforcing and monitoring these requirements, and ensuring continued improvement in educational outcomes for children with disabilities who are eligible for special education and related services. The main features of this system should be explained in terms of the aspects of accountability, the role of the agency that has responsibility for accountability of the RSEPI, and main steps or procedural safeguards that might be considered to make sure that school districts and the service providers follow these regulations. Additionally, the Ministry of Education should annually evaluate the quality of special education services and present a report that explains these services to public agencies. This report might assist these agencies in providing effective best practice services, and helping them improve their provision of special education services to students with disabilities. Another suggestion is to address critical elements of successful inclusion, such as accommodation and instructional modifications of general curriculum, and collaborations. Furthermore, the stakeholders’ perspectives toward inclusion should be examined through more research to determine the best ways to enhance their perspectives of how to be more supportive of students in a general education setting. Procedures to determine eligibility for special education services should be based on the findings of a multidisciplinary team as well as the other issues discussed above. Finally, schools should consider providing related services in support of their IEPs, particularly occupational, physical, and speech–language therapy.

REFERENCES

Al-Abdulwahab, S. S., & Al-Gain, S. I. (2003). Attitudes of Saudi health care professionals toward people with physical disabilities. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 14(1), 63–70.

Al-Ahmadi, N.A. (2009). Teachers’ perspectives and attitudes towards integrating students with learning disabilities in regular Saudi public schools. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from http://etd.ohiolink.edu

Al-Quraini, T. (2012). Factors that are related to teachers’ perspectives towards inclusive education of students with severe intellectual disabilities in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Research in Special Education Needs. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01220.x/abstract

Al-Ajmi, N. S. (2006). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Administrators’ and special education teachers’ perceptions regarding the use of functional behavior assessment for students with mental retardation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

Al-Demadi, A., & Al-Shinawi, M. (1989). Types of attitudes toward people with physical disability among students in King Saud University. Journal of College Education, 4(2), 40–62.

Al-Gain, S. I., & Al-Abddulwahab, S. S. (2002). Issues and obstacles in disability research in Saudi Arabia. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 13(1), 45–49.

Al-Herz, M. M. (2008). Achievement of goals of the individualized education program (IEP) for students with mental retardation and related difficulties. Master’s thesis. Retrieved from http://www.dr-banderalotabi.com/new/admin/uploads/2/dov17-5.pdf

Al-Marsouqi, H. A. (1980). A facet theory analysis of attitudes toward handicapped individuals in Saudi Arabia. Dissertations Abstracts International: Section C, Education, 41(9), 8726431A.

Al-Mousa, N. A. (2008). Development process of special education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: From segregation to integration. Dubai, United Arab Emirates: Dar Alqlam Co.

Al-Mousa, N. A., Al-Sartawi, Z. A., Al-Adbuljabar, A. M., Al-Batal, Z. M., & Al-Husain, A. S. (2006). The national study to evaluate the experiment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in mainstreaming children with special educational needs in public education schools. Retrieved from http://www.se.gov.sa/Inclusion.aspx

Almuaqel, A. (2006). Perception of parents, education teachers, and rehabilitation counselors of the individualized transition plan (ITP) for students with cognitive delay. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Idaho, Idaho, Moscow.

Al-Muslat, Z. A. (1987). Educators’ attitudes toward the handicapped in Saudi Arabia. Dissertations Abstracts International: Section C, Education, 48(11), 264781A.

Al-Nahdi, G. H. (2007). The application of the procedures and standards of assessment and diagnosis in mental education institutes and programs as regards Regulatory Principles of Special Education Institutes and Programs in Saudi Arabia. Master’s thesis. Retrieved from http://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/alnahdi/DocLib/Forms/AllItems.aspx

Al-Otaibi, B., & Al-Sartawi, Z. A. (2009). Related services that are needed for the students with multiple disabilities and their families in Saudi Arabia. Retrieved from http://www.drbanderalotabi.com/new/1/pdf

Alquraini, T. A. (2007). Feasibility and effectiveness of related services that are provided to the students with mental retardation in public schools. Master’s thesis. Retrieved from http://www.drbanderalotaibi.com/new/admin/uploads/2/5.pdf

Alquraini, T. A. (2010). Special education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges, perspectives, future possibilities. International Journal of Special Education, 25(3), 139–147.

Alquraini, T. A. (2013). Legislative rules for students with disabilities in the United States and Saudi Arabia: A comparative study. International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education, 2(6), 601–624.

Al-Sartawi, A. M. (1987). Attitudes of students at college of education in King Saud University toward people with mental retardation. Journal of College Education, 2(7), 112–127.

Al-Sartawi, Z., & Grageah, S. (2010). The provision of the related services for children with autism and their families. Journal of College of Education. , Ain Shamas University, 2(40), 210–225.

Al-Wabli, A. M. (1996). Related services that are provided for students with mental retardation in special education institutes in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Education, 20(3), 191–232.

Central Department of Statistics and Information Population and Vital Statistics. (2011). Population and housing characteristics in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Retrieved from http://www.cdsi.gov.sa/pdf/demograph1428.pdf

Hanafi, A. (2008, June). Actual related services for students with hearing disability in Saudi Arabia. Paper presented at the first scientific conference of mental health in the College of Education, University of Banha, Egypt. Retrieved from http://faculty.ksa.edu.sa/70443/Pages/cv.aspx

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1997. (1997). Pub. L No.105-17, 111, Stat. 37.

Marza, H. M. (2002). The effects of early intervention, home-based, family-centered, support programs on six Saudi Arabian mothers with premature infants: The application of interactive simulation strategies. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, MD.

Ministry of Education of Saudi Arabia. (2002). Regulations of special education programs and institutes of Saudi Arabia. Retrieved from http://www.se.gov.sa/rules/se_rules/index htm

Ministry of Education of Saudi Arabia. (2012). General directors of special education. Retrieved from http://www.se.gov.sa/hi/

Prince Salman Center for Disability Research. (2004). Kingdom of Saudi Arabia provision code for persons with disabilities. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Prince Salman Center for Disability Research.

Sadek, F. M., Mousa, F. A., & Sesalem, K. S. (1986). Attitudes of Saudi Arabian society toward people with blindness. Journal of College Education, 3(6), 51–77.

Yell, M. L. (2006). The law and special education (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall Publishers.