SPECIAL EDUCATION TODAY IN TURKEY

Macid Ayhan Melekoğlu

ABSTRACT

As a result of human right movements, the importance of special needs of individuals with disabilities has become more prominent in many countries in the world. Hence, endeavors of people with disabilities, their family members, and advocates to seek accessible communities and equal opportunities for education, as well as, job placement have been widely accepted as human rights for individuals with disabilities. Consequently, establishing barrier-free environments and inclusive societies for people with disabilities have become important indicators of social development of countries. Besides, since education is considered as a fundamental human right, the importance of providing special education for children with disabilities has been recently realized by many nations (United Nations. (2006). World programme of action concerning disabled persons. New York, NY: United Nations). Turkey is one of those countries that have quite recently started to invest in special education services for its citizens with disabilities. This chapter focuses on the development, as well as the current state of special education in Turkey. Included in this development are the following sections: origins of Turkish special education, prevalence and incident rates, trends in laws and regulations, educational interventions, working with families, teacher preparation, progress that has been made, and special education challenges that exist.

INTRODUCTION

Turkey, known as the Republic of Turkey, is located in Western Asia. It is also known as the bridge between Europe and Asia which makes it a country of geostrategic importance. The actual area of Turkey is 814,578 square kilometers, of which 790,200 are in Asia and 24,378 are located in Europe. According to Turkey’s most recent census, the country’s population is nearly 75 million (Turkish Statistical Institute, 2012). The vast majority of citizens are Muslims. The country’s official language is Turkish. The country is a founding member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and Group of 20 (G-20) major economies. Furthermore, Turkey has the world’s 15th gross domestic product (GDP) (World Bank, 2012). In addition, Turkey is a candidate country for the European Union (EU) membership following the Helsinki European Council.

Turkey is a republic based on secular, democratic, and pluralistic principles. The Turkish Republic was established in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and has a parliamentary system of government that constitutionally protects personal rights and freedoms. As a result, Turkey has the divisions of power that one would expect: judicial, legislative, and executive. The Constitution of the Republic of Turkey (1982) is the supreme law of the country. In terms of educational structure, “formal education” and “informal education” are two main parts of the Turkish education system. The typical education that citizens are exposed to is in school environments defined as formal education and based on specific ages. Educational environments that provide early childhood, primary, secondary, or higher education are classified as formal education. However, there are informal education environments which consist of academic and nonacademic education and vocational training workshops and centers available for people who have never received formal education, dropped out of school at any level, or graduated from an informal school system. Additionally, all Turkey educational activities are governed by two institutions, the Ministry of National Education (MEB, Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı) and the Higher Education Council (YÖK, Yükseköğretim Kurulu). All public and private institutions that provide education, including special education, from early childhood to secondary level operate under the responsibility and control of the MEB, while all higher education institutions are controlled by the YÖK (Melekoğlu, Cakiroglu, & Malmgren, 2009).

ORIGINS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION

The Republic of Turkey is a considerably young country which was established in 1920; however, Turkish people have existed in history for centuries. In fact, when some individuals with intellectual disabilities were exiled or burned in Western countries during the Middle Ages, there were healing centers established in the lands of Turkish people. Especially after accepting the religion of Islam, Turkish people placed strong emphasis on human health and provided free access to hospitals for individuals in Turkish countries such as Seljuks of Anatolia and the Ottoman Empire (Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011). In terms of provision of special education, gifted and talented children were systematically selected and educated in the Enderun School (Enderun Mektebi) which was founded in 1455 by Fatih Sultan Mehmed, the Sultan of that time, and served during the era of the Ottoman Empire (Melekoğlu et al., 2009). Furthermore, conscious and systematic special education services for children with disabilities started in 1889, for children with hearing impairments in a school that was established as a part of the Istanbul Trade School under the leadership of Mister Grati (Grati Efendi) who was a citizen of Austria and principal of the school. After one year, another section was opened in the school for students with visual impairments. This special education school served students with disabilities for 30 years and was shut down in 1919 (Akçamete, 1998; Akkök, 2000; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011; Cavkaytar & Diken, 2012; Eripek, 2012).

Right after the official establishment of the Republic of Turkey, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, a private association started a special education school called the “School for Deaf-Mute and Blind” for children with hearing impairments and visual impairments in Izmir in 1921. The school was turned over to the Ministry of Health and Social Aid in 1924 and continued to provide services until 1950. Since the provision of special education services was considered the responsibility of the Ministry of Health and Social Aid at that time, special education schools and institutions were functioning under the management of that ministry until 1950. Afterwards, special education became a duty of the MEB and the “School for Deaf-Mute and Blind” was transferred to this ministry in 1951. In the meantime, to improve participation of blind people into the society, the first blind union, called Altınokta Körler Derneği (Six Dots Foundation for the Blind), was established under the leadership of Associate Professor Mitat Enç in 1950 (Akçamete, 1998; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011; Şahin, 2005). Professor Enç, who had a visual impairment, was an important pioneer in the field of special education because of his endeavors in the development of university special education programs and his service at the MEB. In the current era, the National Conference of Special Education is organized each year in remembrance of Associate Professor Mitat Enç and the 23rd National Conference of Special Education was held in Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University in 2013 (http://oek2013.ibu.edu.tr).

As a recently established country, Turkey started to exhibit striking and critical developments in the field of special education after 1950. First of all, the transfer of responsibility for special education from the Ministry of Health and Social Aid to the MEB reflected the government’s interest in making education of individuals with disabilities a major issue of education rather than a health-related issue. Starting in 1950, special education services were carried out by a branch office of the General Directory of Elementary. In addition, a systematic teacher training structure was initiated at the Gazi Education Institute in Ankara by forming the Department of Special Education in 1952. Also, the section of the “School for Deaf-Mute and Blind” for children with visual impairments was moved to a building that is currently known as the Estimesgut Orphanage in Ankara, the capital of Turkey, in 1951 and then, relocated to a building at the Gazi Education Institute in 1952. The Department of Special Education at the Gazi Education Institute admitted 40 students to train as the first special education specialists of the country. However, after two years of training students, the department was shut down in 1955 (Şahin, 2005).

However, schools continued to be opened for children with visual and hearing impairments, and a selection procedure was developed for children with intellectual disabilities which allowed them to participate in the education system as well. The first psychology clinic, which is currently called the Guidance and Research Center (RAM, Rehberlik ve Araştırma Merkezi), was formed in Ankara in 1955 to evaluate educable children with intellectual disabilities, examine other students with special needs, and provide guidance for these students. Consequently, a special education classroom was formed for children with intellectual disabilities in the Ankara Kazıkiçi Bostanları Primary School in 1955 (Şahin, 2005). Soon after, additional special education classrooms were established for students with intellectual disabilities in the Yeni Turan and Hıdırlıktepe Primary Schools in Ankara in 1955. Eventually, these classrooms became the first examples of incorporating the special education classroom model in regular education schools (Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011).

In 1957, the Children in Need of Protection Law (No. 6972) was enacted, and article 22 of the law indicates that the MEB was required to provide necessary precautions for children with special education needs who were considered children in need of protection. Also, the rights of individuals with disabilities to receive special education were secured in the amended 1961 Constitution by article 50 which states that the government must take necessary precautions for individuals with special education needs to make them beneficial to the society.

In 1961, another law important to the development of special education was enacted, namely, the Elementary and Education Law (No. 222). This law officially indicated the special education needs of children with disabilities required compulsory education age by mentioning that children who are at the compulsory education age and have disabilities due to intellectual, orthopedic, mental, and social deficits need to be provided special education (Akkök, 2000; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011). Of note in the development of the above laws and article 50 was the advocacy influence of The Blind Union, Altı Nokta Körler Derneği (Six Dots Foundation for the Blind), which stressed the need for inclusion provisions regarding individuals. In addition, the Blind Union developed and implemented the first workshop day shelter system for individuals with disabilities in Turkey (Şahin, 2005).

Initial steps for the education of gifted education occurred in the 1956 Education of Gifted Children in the Fine Arts Law (No. 6660). This law stated that the government was responsible for the education of gifted children in the fine arts. Due to a lack of gifted educational resources, gifted children were sent abroad to receive the necessary education for 17 years. While this law is still in force, the government stopped sending these children after 17 years of implementation (Şahin, 2005). Starting in the 1963–1964 school year, gifted students were selected from primary schools in Ankara and Istanbul and educated in separate special education classrooms with a special curriculum. However, this educational practice ended in 1968. A few years later, another attempt was initiated to provide gifted classrooms to meet the skills of gifted students in primary schools but those attempts were stopped in 1972 (Şahin, 2005).

The importance of special education in Turkey became even more evident in 1980, when MEB directed the Department of General Directorate of Elementary Education to make special education services a division rather than a branch. Soon after this, Turkey’s first special education law, namely, the Children with Special Education Needs Law (No. 2916) was enacted in 1983. This law was supported by many constituted special education regulations and provisions. In fact, the Turkey Constitution was amended in 1982 to include special education provisions that are still in force today such as article 42 that states the Constitution is responsible for taking necessary precautions for individuals with special education needs to make them beneficial to the society (Akçamete, 1998; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011; Vuran & Ünlü, 2012).

Although endeavors for training special education specialists were interrupted in the 1950s, many educators including first graduates of the Department of Special Education at Gazi Education Institute contributed to the development of special education in Turkey. These educators trained many special education teachers for the field, disseminated various special education implementations in the education system, and made significant contributions to the establishment of national politics on special education. These educators include the pioneering university work of Associate Professor Mithat Enç, Professor Yahya Özsoy, and Professor Doğan Çağlar, who helped establish college special education programs, as well as MEB professionals, Şaban Dede and Hasan Karatepe, who made great contribution to the developments of the national special education system.

After the innovative and pioneering efforts of the above individuals, other universities established special education programs in Turkey with the help of many talented professors. For example, Professor Şule Bilir helped constitute the Division of Special Education under the Department of Child Development at the prestigious Hacettepe University, in Ankara in 1978. This special education division has been a leading division in training academicians, child development specialists, and teachers in the field of special education in Turkey for many years. Also, Professor Ayşegül Ataman and Professor Ümit Davaslıgil are well-known pioneers, who made great contributions in the area of special education in the Turkish education system (Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011).

By the 1990s, the development of special education gained further momentum due to the increased number of trained personnel, an increase in conducted studies, and a fury of published research papers in Turkey. For instance in 1965, there were only 55 associate degree graduates, three master’s graduates, and one doctoral graduate in the field of special education. This number increased to 625 teacher certificate holders, 187 bachelors graduates, 66 master’s graduates, 16 doctoral graduates, 2 assistant professors, 6 associate professors, and 5 professors in 1990 (Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011).

Furthermore, Köksal Toptan, who was the Minister of MEB between 1991 and 1993, put great emphasis on special education and the country’s most comprehensive works were carried out during this period. These works resulted in the targeted employment of workers in special education, the securing of employee rights for individuals with disabilities, and a vast improvement in the quality and quantity of special education institutions. In addition, necessary tools and materials were developed and provided for special education practices and new implementations were started in the field of special education. Also, a new service, namely, the General Directorate of Special Education, Guidance and Advisory Services was established in the Central Ministry Organization in 1992 (Akçamete, 1998; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011). Further, Professor Necate Baykoç-Dönmez, who was an academician in Hacettepe University, was appointed as the general director of the above service between 1992 and 1995, and she initiated many reforms in the field of special education in Turkey.

The above aspects had an effect on the acceptance and value of inclusion practices in Turkey. This was evident when the MEB accepted inclusion practices as an important concept for special education. The ministry supported the dissemination of information about the importance of inclusion for students with disabilities into regular education in schools across the country. In essence, inclusion practices were viewed as a means to nourish awareness in the society and promote consciousness for the needs of people with disabilities. The importance of this practice was further enhanced when the Turkish government proclaimed 1993 as the Year of Special Education (Akkök, 2001). It is noteworthy that only a few years after this proclamation, the 1997 Special Education Regulation Law (No. 573), which is currently in force, was enacted. Due to this law, the number of private special education and rehabilitation centers (özel özel eğitim ve rehabilitasyon merkezleri) escalated because the government started to pay the special education, rehabilitation, and therapy services expenses provided by these centers (Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011; Vuran & Ünlü, 2012). Lastly, based on the law, the MEB enacted the Special Education Services Regulation in 2006 which delineated current definitions of special education categories and terms (Diken & Batu, 2010). These MEB categorical definitions of exceptionality (Çuhadar, 2012; MEB, 2006) follow. An individual with an intellectual disability (zihinsel yetersizliği olan birey) is defined as one who has an IQ score at least two standard deviations below 100, and limited performance or deficiencies in conceptual, social, and practical adjustment skills, and who manifests those characteristics during the development period before the age of 18 years. In addition, individuals with intellectual disabilities are classified into four categories: mild intellectual disabilities (hafif düzeyde zihinsel yetersizlik), moderate intellectual disabilities (orta düzeyde zihinsel yetersizlik), severe intellectual disabilities (ağır düzeyde zihinsel yetersizlik), and very severe intellectual disabilities (çok ağır düzeyde zihinsel yetersizlik). An individual with multiple disabilities (birden fazla yetersizliği olan birey) is a person with disabilities in more than one domain. A person with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (dikkat eksikliği ve hiperaktivite bozukluğu olan birey) is defined as one who shows attention deficit, over activity, hyperactivity, and impulsivity characteristics that are not appropriate for one’s age and developmental level in at least two contexts for a minimum of six months before the age of 7 years. An individual with speech and language disorders (dil ve konuşma güçlüğü olan birey) is depicted as a person who displays problems in the use of speech, acquisition of speech, and communication. A person with emotional and behavioral disorders (duygusal ve davranış bozukluğu olan birey) is defined as one who manifests emotional reactions and behaviors that vary significantly from the social and cultural norms. An individual with a visual impairment (görme yetersizliği olan birey) is a person who has partial or total loss of vision. Whereas, a person with a hearing impairment (işitme yetersizliği olan birey) is one who experiences problems with acquisition of speech, use of speech, and communication due to partial or total loss of hearing sensitivity. An individual with orthopedic disability (ortopedik yetersizliği olan birey) is person with movement deficiencies due to dysfunction in muscular, skeleton, and joint systems as a result of disease, accident, and genetic problems. A person with autism (otistik birey) is an individual with significant deficiencies in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communications, and interest and activities. An individual with a specific learning disability (özel öğrenme güçlüğü olan birey) is one who experiences academic difficulties, which emerge in one or more knowledge acquisition processes such as understanding and using written or oral language, listening, speaking, reading, spelling, concentrating, attention, or performing mathematical operations. There is separate special education category for a person with cerebral palsy. A person with cerebral palsy (serebral palsili birey) has disabilities in motor skills that are connected to dysfunctions in muscular and nervous systems due to pre-, peri-, or postnatal brain damage. An individual with chronic health problems (süreğen hastalığı olan birey) is a person with health problems that require continuous or long time nursing and treatment. Lastly, a gifted individual (üstün yetenekli birey) is a person who shows high level performance in intelligence, creativity, art, sports, leadership capacity, or specific academic domains compared to his/her peers.

An examination of Turkey’s special education literature reveals that definitions of special education categories can include those based upon the Special Education Services Regulation (MEB, 2006) and definitions from the US’s special education literature that is incorporated in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA, 2004), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association, 2004), and US text books (see Akçamete, 2009; Ataman, 2005; Baykoç, 2011; Diken, 2010a, 2010b; Rotatori, Obiakor, & Bakken, 2011; Sucuoğlu & Kargın, 2010). In fact, many laws and regulations related to special education in Turkey have been deeply influenced by US laws and regulations about special education such as the least restrictive environment (LRE) and individualized education programs (IEPs).

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENT OF STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

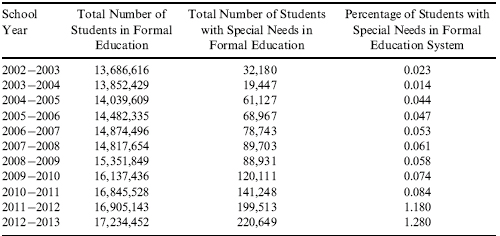

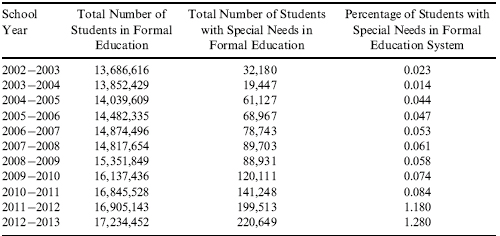

In terms of the number of students in special education, Turkey publishes overall statistics for special education annually. There is no official publication of the number of students in each special education category (Cakiroglu & Melekoğlu, 2013). However, the official publication includes the number of students in separate and inclusive school settings. According to the National Statistics there were 32,180 students with special needs in formal school system in the 2002–2003 school year in Turkey (MEB, 2003). This number has increased to 220,649 in the 2012–2013 school year (MEB, 2013). In the current education system, approximately 7% of all children with special needs are included in formal and informal education settings in Turkey (Baykoç-Dönmez, 2011). In fact, a steady increase in the number of students with special needs in formal education system was reported when the annual statistical reports were analyzed (see Table 1) by Cakiroglu and Melekoğlu (2013). These researchers used a linear regression analysis to determine the extent to which there is a linear relationship between school years and the total number of students with special needs for each school year. The regression analysis indicated a significant increase in the number of students with special needs from 2002–2003 to 2012–2013 (R2 = 0.895, F[1,10] = 86,513, p < 0.000). This model accounted for 89.5% of variance in the increase, and the researchers reported that the school year was a significant predictor variable that had a significant impact on the increase in the numbers of students with special needs (β = 0.952, p < 0.000). These findings show that the increase in the numbers of students with special needs in formal education has been statistically significant over the last decade in Turkey (Cakiroglu & Melekoğlu, 2013).

Table 1. Students with Special Needs in Formal Education in Turkey.

When the number of students in segregated school settings was examined in the 2012–2013 school year, results show the following distribution by exceptionality: 1,006 early childhood education students; 3,577 students with hearing impairment; 1,406 students with visual impairments; 642 students with orthopedic disabilities; 2,658 students with mild intellectual disabilities; 14,427 students with moderate and severe intellectual disabilities including autism; and 68 students with adaptation problems (including emotional and behavioral disorders).

In addition to those students with disabilities who are enrolled in formal schooling, there were students with special needs that are educated in informal schools. Currently, 31,376 students are categorized as receiving informal education. Of this number, 11,268 are gifted students enrolled in 66 after regular school Science and Arts Centers. In addition, 20,108 students with disabilities received informal education in 152 private special education schools in the 2012–2013 school year according to the MEB (2013).

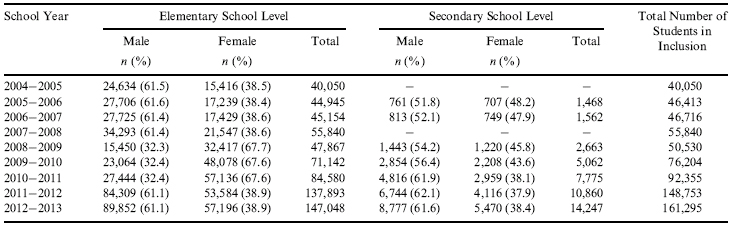

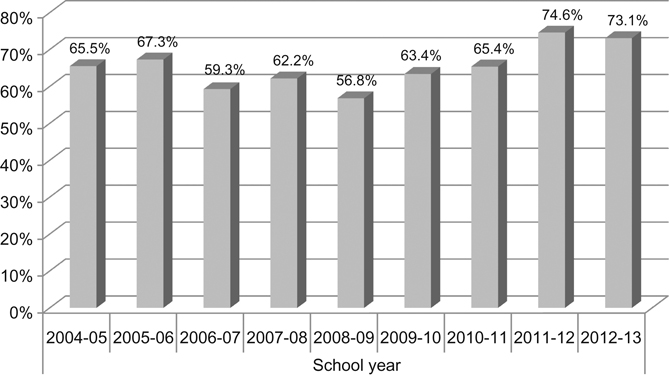

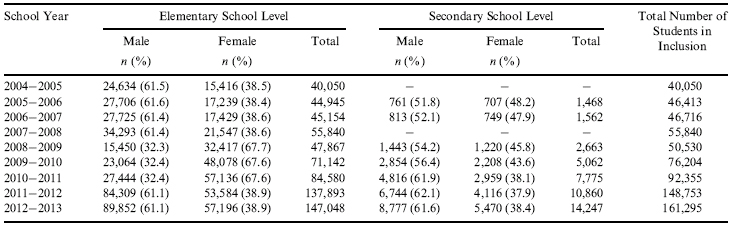

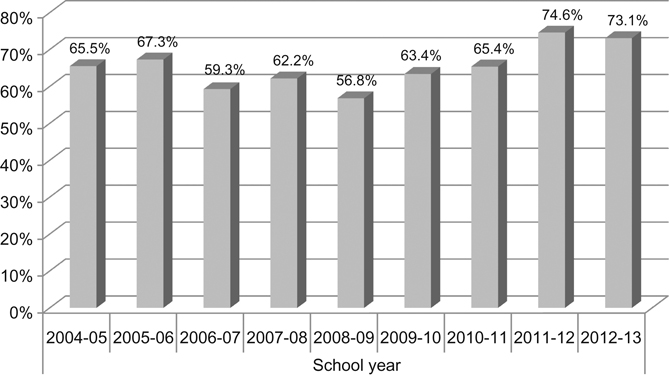

Inclusion practices are also widely accepted in Turkey’s education system. However, the official publication of national enrollment statistics related to inclusive education includes only overall numbers. Data for inclusion education has been available since the 2004–2005 school year but only at the elementary level. There were 40,050 students with special needs in inclusive settings in the 2004–2005 school year (MEB, 2005). This number increased to 92,355 in the 2010–2011 school year (MEB, 2011a), and then increased to 161,295 in the 2012–2013 school year (MEB, 2013; see Table 2 for details). In terms of the percentage of students with special needs in inclusion among all students in special education, the rate has always been more than half since the 2004–2005 school year and has increased to almost three quarters of all students with special needs during the last two school years. The percentage of students with special needs in inclusion can be examined in Fig. 1.

Table 2. Students with Special Needs in Inclusive Classrooms in Turkey (by MEB).

Note: “–” indicates absence of data.

Fig. 1. Percentage of Students with Special Needs in Inclusion in Turkey.

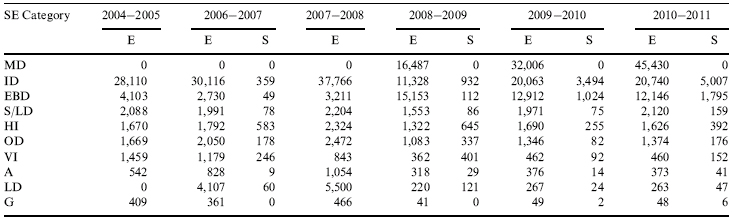

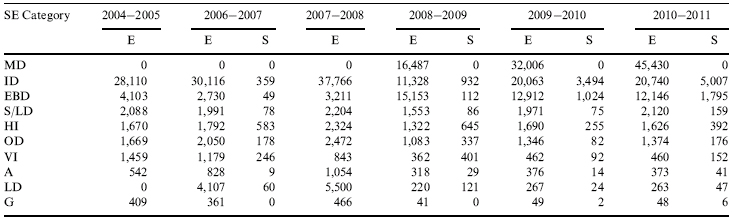

Although, the officially published national statistics do not include data regarding separate special education categories in Turkey, a secondary data set obtained from the Turkish Ministry of National Education Strategy Department was analyzed to gather statistical details about special education categories in inclusion in Turkey (MEB, 2011b). The raw data about special education statistics was officially requested with a written application by the chapter’s author to the MEB for analysis and research purposes. Details about the number of students in each special education category in inclusive classroom between the 2004–2005 and 2010–2011 school years can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Number of Students in Each Special Education Category in Inclusive Classrooms in Turkey.

Note: SE = special education; E = elementary school level; S = secondary school level; MD = multiple disabilities; ID = intellectual disabilities; EBD = emotional and behavioral disorders; S/LD = speech and language disorders; HI = hearing impairments; OD = orthopedic disabilities; VI = visual impairments; A = autism; LD = specific learning disabilities; G = gifted.

The results of the data analysis indicate that there has been a steady increase in the number of students with special needs in inclusion education. It is noted that the fastest increasing special education category is multiple disabilities. Further it should be noted that many students with special needs have been diagnosed with a secondary disability over the years, and categories such as learning disabilities, autism, or intellectual disabilities, the number of students has either declined or stayed steady even though the number of students in inclusion has been escalating.

TRENDS IN LAWS AND REGULATIONS IN TURKEY

The Constitution of the Republic of Turkey has included laws and regulations regarding special education for individuals with disabilities since its first enactment in 1926. Special education was first addressed in Turkish Civil Law (No. 743) that was enacted in 1926. This law required parents to raise their children with physical or intellectual disabilities and they would receive appropriate education. In 1961, the Constitution was amended to incorporate rules about people with special needs that was proposed by the Blind Union. The formal regulation about education of individuals with special needs was explained in articles 42, 50, 62 of the Constitution. For the first time, these articles included provisions related to regulations regarding special education services (Şahin, 2005). Then in 1961, The Elementary and Education Law (No. 222) was enacted. This law indicated that all schools and classes must accommodate children with special needs. Additionally, article 12 specified that provision of special education services should be secured for students with intellectual, psychological, physical, emotional, and social disabilities (Senel, 1998).

In addition to the above, a number of laws and regulations that govern issues about employment of people with disabilities have been enacted. For example, regarding employment of people with disabilities, article 50 was enacted in the Employment Law (No. 1475). This law indicates that a business that employs 50 or more employers needs to hire 2% of their workforces from people with disabilities as well as provide appropriate working conditions based on their specific needs (Şahin, 2005).

The Constitution of the Republic of Turkey was amended in 1982, and it currently includes several vital regulations for individuals with disabilities; especially, human rights which address the rights of individuals with special needs. Right after the amendment of the constitution, the first comprehensive law regarding individuals with disabilities was enacted in 1983. This law entitled The Children with Special Education Needs Law (No. 2916) consisted of sections on: definitions, principles, special education institutions, duties about special education, diagnosis, placement, and monitoring of children with special education needs. The law stayed in force until a new law, namely, The Special Education Law was enacted in 1997 (Akçamete, 1998; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011).

The Special Education Law (No. 573) published in The Official Gazette (No. 23011) in 1997. The law’s aim is to regulate principles and provisions regarding the rights of persons with disabilities to receive general and vocational education according to the general goals and basic principles of the Turkish National Education System. The law defines diagnostic, special education assessment, and placement processes of special education. In addition, educational principles regarding early childhood, elementary, secondary, higher, and informal education are specified for individuals with special needs. Further, the law delineates educational settings and highlights educational principles about inclusive education. Other issues illustrated by the law include: the active participation of family members in all aspects of their child’s special education processes; the importance of contributions of special education organizations to the development of special education policies; the incorporation of special education services into social interaction; and the adaptation processes. In essence, this law provides the basic principles of special education which include that: (a) special education needs to be viewed as an absolutely necessary part of general education; (b) all students with disabilities should receive required special education services regardless of the severity of the disability; (c) early intervention is critically important for better provision of special education services; (d) all students with special needs should have IEPs that meet their specific needs; (e) students with special needs should be placed in least restrictive educational environments with their nondisabled peers; (f) vocational education and rehabilitation services need to be continuous for students with special needs; and (g) education services that are provided in all educational levels for students with special needs should be planned by the relevant institutions (Akçamete, 1998; Akkök, 2000; Baykoç-Dönmez, 2000). These principles are clearly outlined in the law and children with special needs are viewed as being a crucial part of public education. Soon after the law was enacted the number of students in inclusion increased. However, due to financial drawbacks and a shortage of trained professionals in the field of special education, these principles have not been fully adhered to and implemented by the professionals, who provide special education services to children with special needs (Melekoğlu et al., 2009).

Another important development for individuals with disabilities in 1996 was the establishment of the Administration for Disabled People which was connected to the Turkish Prime Ministry. The purpose of this administration is to execute services for individuals with disabilities regularly, effectively, and efficiently by ensuring cooperation and coordination between national and international institutions and organizations; support generation processes of national policies about individuals with disabilities; and identify problems of individuals with disabilities and find solutions for these problems (Akçamete, 1998; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011). This administration was transferred to the Ministry of Family and Social Policies in 2011 and became the General Directorate of Disabled and Elderly Services.

In 2006, the Special Education Services Regulation was enacted by the MEB (2006). This regulation consists of nine parts and provides specific details about provisions of special education services in the Turkish education system. General provisions, educational assessment and placement, special education services board and duties, working procedures, and principles of the special education assessment board, educational practices through inclusion, educational services, institutions, staff, duties, authority and responsibilities, education and training, and miscellaneous and final provisions are parts of the regulation. As mentioned earlier, this regulation includes definitions of many terms, including special education categories, about special education. According to this regulation, the goal of special education includes: (a) educating individuals to perform their roles in the society, establish good relations with others, be able to work in cooperation, adapt to their environments, and be productive and happy citizens; (b) developing basic living skills to live independently in the community and become self-sufficient; and (c) preparing individuals for upper levels of education, business and professional fields, and life in line with the educational needs, capabilities, interests, and abilities by using appropriate educational programs and special methods, personnel, and equipment.

A close examination of the above laws and regulations regarding special education points to a great impact from special education legislations that originated in the United States and the United Kingdom (Akçamete, 1998). In fact, many Turkish legislative acts were modeled after US special education laws such as the IDEA (2004) because a number of influential special education Turkish academicians and special education experts, who completed their graduate studies in special education at universities in the United States, were involved in the formulations of Turkey special education laws. In terms Turkey’s special education laws and regulations, the legal infrastructure was vigorously established and enacted by the endeavors of advocates, academicians, and politicians rather than individuals with disabilities and/or their family members. Therefore, the implementations of these laws and regulations are not controlled by people and family members receiving those services. Consequently, even though the quantity of special education services and institutions has quickly increased, the quality of special education services is still not at a desired level in Turkey.

EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTIONS IN TURKEY

As seen in the official Turkey statistics about students with special needs in special education, almost three quarters of students are educated in inclusion classrooms and the rest are placed in segregated schools or classrooms. The 2006 Special Education Services Regulation (MEB, 2006) indicates the importance of inclusion by describing it as a special education practice based on the idea that students with special education needs should be educated with their nondisabled peers in public and private early childhood, elementary, secondary, and adult education institutions that include necessary support services that enhance their educational well-being. In fact, dissemination of inclusion practices has been widely supported in the last decade, and special education and inclusion practices are developing rapidly in the Turkish education system since the enactment of the special education law. Even though inclusion practices are not presently at the desired level of quality, dissemination information about inclusive education is embraced as an important educational policy (Diken & Batu, 2010; Melekoğlu, 2013; Melekoğlu et al., 2009; Sucuoğlu & Kargın, 2010). However, studies about inclusion practices in Turkey have been limited to: investigation of opinions and suggestions of teachers regarding inclusion of children with intellectual disabilities; the impact of inclusion practices on children with intellectual disabilities; and factors influencing social acceptance of children with intellectual disabilities by their normally developing peers (Diken & Batu, 2010).

While inclusive educational intervention is experienced by the majority of students with disabilities, there are quality primary and middle school educational interventions for students with disabilities who are in self-contained classrooms. For instance, in the 2012–2013 school year, a total of 25,477 students were educated in self-contained classrooms (MEB, 2013). Most of these classrooms are cross-categorical self-contained classrooms while some are non-categorical classrooms. Self-contained classrooms usually consist of students with moderate and/or severe intellectual disabilities, autism, visual impairments, hearing impairments, and multiple disabilities. The number of students in each classroom is usually between 8 and 10 but those numbers can vary depending on the location of the school. Typically, there is one special education teacher in most classrooms.

Meaningful primary and secondary educational intervention is also provided at residential schools for children with visual impairments, hearing impairments, and orthopedic disabilities. Almost all of the students with hearing impairments use hearing aids in their classrooms. Also, students with visual impairments can access brailed educational documents in segregated settings.

Similar to other countries, educational intervention at private special education and rehabilitation centers is widespread in Turkey. Students with disabilities in these placements can receive individual and/or group education and rehabilitation or therapy services. The government covers the expenses of these services for 2–3 hours per week. If families desire additional hours of services, they must pay for it (Vuran & Ünlü, 2012). Families with gifted children receive special education in Science and Arts Centers after their regular education hours. As of the 2012–2013 school year, there are 66 Science and Arts Centers serving 11,268 gifted and talented children (MEB, 2013). Typically, instruction for these students involves exposure to specific academic topics and/or accelerated learning opportunities in various ability domains.

In terms of teaching techniques for students with special needs such as a specific learning disability, there is no special instructional techniques that are universally employed (Özyürek, 2005). This occurs because most general education teachers working in inclusive classroom usually do not receive any educational support in terms of best special education practices and many have little awareness of teaching techniques for students with special needs. In contrast, students with special needs, who are instructed by teachers with special education training, are exposed to quality education. For example, many of these teachers employ best practice special education techniques such as applied behavior analysis (ABA) methods (see Anderson, Marchant, & Somarriba, 2010). Further, the Turkish education system has started discussions about adopting the Response to Intervention (RTI) model (see Kauffman, Bruce, & Lloyd, 2012) that is employed in the United States.

All special education experts and academicians emphasize the importance of early intervention and prevention programs, and the Special Education Services Regulation has aspects related to early childhood special education. However, there is no officially practiced and supported early intervention program or prevention system throughout Turkey and there are only a couple of early childhood institutions that provide this service to young children with special needs. Thus, even though the critical importance of early intervention and prevention programs for the success of special education practices are well known, the lack of those programs is a significant deficiency in the special education field in Turkey (Baykoç-Dönmez, 2011; Er-Sabuncuoglu & Diken, 2010).

Another common special education practice, namely, a systematic transition procedure for individuals with disabilities from school to adult life, is not occurring in Turkey. While school placements of individuals with disabilities are coordinated by the RAMs in cooperation with parents/primary carers of these individuals, the transition of students with special needs is not systematically planned. Positively, after their school completion, students with disabilities can attend vocational schools or training centers until age 23 years. After completing their work training in these programs, there is no transition system to place them in a job. The options for adult individuals with disabilities who complete vocational schools or training centers are: living in an adult education institution governed by the General Directorate of Life Long Learning; living with their family members; and living in a care center.

WORKING WITH FAMILIES OF INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES IN TURKEY

Parents or primary carers of individuals with disabilities have legal rights related to: special education assessment of their children; school placements of their children; and the preparation of individualized education plans for their children. The Special Education Services Regulation (MEB, 2006) stresses the active participation and education of families under the principles of special education. In addition, the regulation indicates that family approval is required for educational assessment and diagnosis of their child. It also emphasizes that the family is an important partner in the cooperation between schools, institutions, and RAMs for efficacy of special education services (MEB, 2006). Since the majority of families of individuals with disabilities are from a low socioeconomic level and have limited education, they are not aware of or do not pursue their legal rights for the education of their children. Further complicating the situation is the fact that most of the families of individuals with disabilities are at a denial or aggression stage rather than an acceptance and adjustment stage in Turkey. Often, these parents are embarrassed to have children with disabilities which interferes with their seeking financial supports or advocating for their children to receive quality special education and become integrated into the society.

Typically, school guidance counselors or teachers work as liaisons with families of children with special needs. For most of the families, their interaction with these experts is limited to participation in parent–teacher conferences and getting periodic information about the annual progress of their children. Such limited interaction becomes problematic because families, who have a child in an inclusive classroom, may encounter resistance or exclusion from families of nondisabled students. Sometimes this negative reaction by parents of nondisabled children leads to their nondisabled students refusing to interact with children who have special needs. Lastly, families are responsible for all stages of special education assessment of their children which can be a problem due to their lack of knowledge about special education.

Studies of families of individuals with disabilities in Turkey have focused on topics such as evaluating the effectiveness of family education programs that are formed to teach a variety of skills to children with special needs; characteristics of families of children with special needs; family education and family guidance; family participation; family anxiety, worries, stress, social support, and resilience levels; family needs; and family attitudes (Meral, 2011).

TEACHERS TRAINING IN SPECIAL EDUCATION

Teacher training in special education in Turkey is a relatively new endeavor. The first attempt for special education teacher training started in the 1952–1953 school year in the Department of Special Education at Gazi Education Institute. This program was open just for primary education teachers with three years of experience. The program involved two years of instruction. Unfortunately, after only two terms of graduating students, the teacher training program ended. This resulted in regular education teachers meeting the special education needs of students until 1980s. These teachers were trained via exposure to in-service training workshops and/or special education certification programs.

A second attempt at formal special education teacher training was initiated by the Educational Sciences Department in the School of Education at Anadolu University in Eskisehir in 1983. This program had its first graduates in the 1986–1987 school year. In 1990, the Department of Special Education was established in the School of Education at Anadolu University. This Department of Special Education has been teaching college students who had an interest in teaching individuals with intellectual disabilities and hearing impairments. Soon afterwards, Gazi University offered special education teacher training programs for college students interested in educating individuals with intellectual disabilities and visually impairments (Akçamete, 1998; Baykoç-Dönmez & Şahin, 2011; Eripek, 2012).

Currently, a four-year undergraduate education is necessary to become a special education teacher in Turkey. Teacher candidates are centrally placed in undergraduate programs based on the results of nationwide higher education exams. Regular teacher candidates are trained by faculty in the Education Department while special education teacher candidates are trained by faculty in the Special Education Department. There are approximately 180 universities in Turkey, and as of the 2013–2014 school year, only 19 of these universities have undergraduate special education departments that offer programs to train special education teachers. Typically, these programs offer training in intellectual disabilities, hearing impairments, visual impairments, and gifted. Almost all offer a program of study in intellectual disabilities because it has the largest special education teacher quota (over 1,500) in the country’s central higher education placement.

The undergraduate programs in special education use preset curriculums that are approved by the YÖK. There are required courses in these curriculums and teacher candidates at times need to fulfill field work for some courses. In addition, these programs require students to complete a teaching practicum over two semesters (28 weeks). All special education teacher candidates who successfully complete a program of study with a 2.0 grade point average have the right to work as a special education teacher. While there is no national teacher certification that is necessary to work in public schools, teacher candidates must take a nationwide teacher placement exam. Based on their exam scores and the national quota in appointment periods, teacher candidates are placed by the MEB.

PERSPECTIVE ON THE PROGRESS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION

Although special education is a considered a new field in the Turkish education system, there are positive developments, as well as, problems in educating students with special needs. First of all, there are sufficient numbers of special education teachers in most of the segregated schools and the RAMs but the current quality of education and assessment processes being practiced needs to be improved. Second, inclusion practices have been rapidly disseminated in general education schools but there are almost no support services in the school for children with special needs nor in-service assistance to the teachers of students in inclusive classrooms. These aspects are problematic because many regular education teachers are not trained about inclusion and/or education of individuals with special needs. Therefore, most of the students with special needs do not receive quality education or in some cases, any education. In addition, the majority of teachers of inclusive classrooms are against inclusion practices, and teachers, administrators, nondisabled peers, and their families often manifest negative attitudes toward children with special needs and their families (Melekoğlu, 2013). Given all the above negative aspects, inclusion practices can be harmful for some children with special needs.

In terms of training special education teachers, there are 19 special education departments training special education teachers in universities but most teachers are educated to work with individuals with intellectual disabilities. Due to this, the current supply–demand balance cannot be achieved. While special education department faculty support other education departments by providing special education foundation and/or inclusion courses there are many university educational departments that do not have a special education expert to offer these courses. Therefore, teacher candidates that graduate from these universities are not well equipped concerning special education and inclusion best practices (Melekoğlu, 2013). Also, even when teacher candidates are exposed to special education courses, the courses are taught from a theoretical perspective rather than a practical knowledge base perspective. Positively, special education teacher candidates receive practical knowledge perspectives and working experience about students with special needs in their last year of college. Even then the teacher candidates have a lot to learn as most do not have any school or society contact with students who have special needs prior to entering college.

Another problem with the teacher training system is the categorical approach that special education programs use to training special education teacher candidates. The categorical system does not allow teacher candidates who study under one category, such as intellectual disabilities, to earn a certificate in another category such as hearing impaired. A more efficient approach that is used in many countries would be to train special education teacher candidates using a cross-categorical approach that would allow them to be certified to teach students from different categories. Also, this approach would help to reduce teacher shortages in some areas of special education. Further, university graduate programs do not allow certified regular education teachers (e.g., history, science) to become special education teachers in Turkey. Hopefully as inclusive education increases, universities will allow non-special education teachers to be trained in special education in a master’s degree program. Such a change would be very logical for regular education teachers with specialities in say math or science to become certified to teach gifted students in these areas especially at the secondary school level.

Unfortunately, there is almost no official government attempt to improve quality of life, employment training, and living arrangements of individuals with disabilities in Turkey. While vocational schools or training centers provide work training for some individuals with disabilities, the training does not comply with contemporary needs of businesses. There are some nongovernmental organizations and municipalities that work on providing opportunities for individuals with disabilities to acquire employment training and a job placement but they are very limited in scope and often result in job failure due to a lack of on the job training, follow up, or sustainable long-term funding. In terms of living arrangements, individuals with disabilities usually stay with their families or in care centers rather than in independent living settings. There is no community independent living arrangement settings such as group homes that have been established by the government for individuals with disabilities.

Positively, funding educational services and certain life aspects from the government has significantly improved for individuals with disabilities and their families in the last decade. For example, all individuals with disabilities are eligible for monthly disability salary if they meet the official requirements for disability. In addition, if the individual with a disability is in need of care, a family member or someone else who provides care to that person can receive a care salary. Also, the government pays education, rehabilitation, or therapy expenses for persons with a disability if the services are provided by private special education and rehabilitation centers (Akçamete, 1998; Vuran & Ünlü, 2012). Furthermore, all medical expenses of individuals with disabilities are covered by the government. Government reforms in funding education and services for individuals with disabilities has improved considerably, however, more needs to be done especially in the employment domain and the quality control of care services.

SPECIAL EDUCATION CHALLENGES

There are nine challenges that remain in special education today in Turkey. These challenges were identified and discussed by experts in the special education field at a recent conference, namely, the Special Education Search Conference, that was held at Anadolu University in November 2013 (Özel Eğitim Arama Konferansı, 2013). The first identified challenge is to establish a new model of training special education personnel. While there are training programs for special education teachers, there are no program to train paraprofessionals who work in special education schools, institutions, and centers. In addition, the current teacher training model does not respond to the needs of the Turkish education system. Further is the need for special education teacher candidates to be trained in cross-categorical programs.

A second challenge is to resolve the academic personnel shortage needs at universities. In many university special education departments, there are only a couple of academicians with doctoral degrees in special education. Additionally, there are many universities that wish to establish special education departments but they cannot find faculty with graduate degrees in special education. There needs to be more information dissemination about graduate special education program offerings. Due to special education teacher shortages, graduate students in special education should be supported financially to encourage other college students to enter into special education.

A third challenge in special education is establishing effective inclusive education. There should be at least one special education teacher in each school to serve as a support person. Also, paraprofessionals should be allowed to work in inclusive classrooms. Teachers of inclusive classrooms need to be comprehensively trained in effective special education best practices and receive necessary support as required.

A fourth challenge in Turkey is the need for early diagnosis and intervention of young students with special needs. Positively, there have been several studies about the adaptation of early intervention programs in Turkey such as the “Small Steps Early Intervention Program,” “Portage Early Education Program,” “Behavioral Education Program for Children with Autism,” “Responsive Teaching,” and “First Step to Success” (Diken, Cavkaytar, Batu, Bozkurt, & Kurtılmaz, 2010; Er-Sabuncuoglu & Diken, 2010; Yıldırım Doğru, 2011) but these programs have not been integrated in the early childhood special education system in Turkey. To accomplish this, there needs to be an official coordination system established between the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of National Education, and the Ministry of Family and Social Politics for early diagnosis and early intervention of children with disabilities. Also, education and rehabilitation centers and schools need to be directed by the government to focus on early intervention and rehabilitation. For this to occur, the MEB needs to establish official procedures, plans, and regulations for early childhood special education and intervention starting at the birth of a child.

The fifth challenge in special education is to develop better family participation and support. Families of children with disabilities should be educated about the child’s disability, rights, interventions, educational practices, and related issues as soon as a disability is diagnosed in children. This education procedure should be operated by the government in a systematic and planned way. In addition, active participation of families in all stages of special education should be secured officially, and if necessary, advocates for families should be integrated into the process.

The sixth challenge in special education today in Turkey is the need for job training and placement of individuals with disabilities. Similar to best practice in many developed countries, the government needs to start planning transition to work plans for individuals with disabilities when these students enter their teenage years. These students need exposure to work training and work environments to increase their success in future job placements. To make this a sustainable process, the government should make agreements for job placements and training procedures of individuals who have disabilities with national and local business entities. In addition, the government should promote public and private shelter workshops and require strict and regular controls of these workshops.

The seventh challenge is dealing with the current deficiency in laws and policies about special education. All existing laws and regulations should be revised to address critical comments made by directors of nongovernmental organizations and experts regarding the needs of the Turkish education system (Eripek, 2012). Also, the government should determine functional policies and be accountable for the implementation of those policies.

Dissemination of research-based practices is the eighth challenge in special education in Turkey. The MEB should play an active role in this process and officially create an environment that introduces and promotes research-based practices in special education and requires educators to use those practices in schools. Additionally, the government should provide funding to universities and community researchers for the investigation of effective special education practices.

The ninth challenge existing in special education is the transition of individuals with disabilities to independent living. The government should plan and coordinate the transition process early on, and train experts about the issue and create adequate environments and a support system for smooth transition of individuals with disabilities to independent living.

In summary, special education in Turkey today has come a long ways and is still in the process of development. There are many challenges remaining in special education in Turkey but those challenges are not completely new in the special education field. Many countries have already handled those problems, and Turkey can study these solutions and adapt them according to national needs and expectations. Positively, there is strong governmental support for special education but more determined administrators are needed for resolving the special education challenges listed at the 2013 Special Education Search Conference. Addressing these challenges will go a long way in fulfilling Turkey’s comprehensive reform in special education.

REFERENCES

Akçamete, A. G. (2009). Genel eğitim okullarında özel gereksinimi olan öğrenciler ve özel eğitim. [Students with special needs in general education schools and special education.] Ankara: Kök Yayıncılık [Kok Publication].

Akçamete, G. (1998). Türkiye’de özel eğitim. [Special education in Turkey]. In and S. Eripek (Ed.), Özel eğitim (pp. 195–208). [Special education.] Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Yayınları [Anadolu University Publications].

Akkök, F. (2000). Special education research: A Turkish perspective. Exceptionality: A Special Education Journal, 8(4), 179–273. doi: 10.1207/S15327035EX0804_5

Akkök, F. (2001). The past, present, and future of special education: The Turkish perspective. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies, 6(2), 15–22.

American Psychiatric Association. (2004). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev. edn). Washington, DC: Author.

Anderson, D. H., Marchant, M., & Somarriba, N. Y. (2010). Behaviorism works in special education. In and F. E. Obiakor, J. P. Bakken, & A. F. Rotatori (Eds.), Current issues and trends in special education: Identification, assessment, and instruction (pp. 157–173). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Ataman, A. (2005). Özel gereksinimli çocuklar ve özel eğitime giriş. [Children with special needs and introduction to special education.] Ankara: Gündüz Eğitim ve Yayıncılık [Gunduz Education and Publication].

Baykoç, N. (2011). Özel gereksinimli çocuklar ve özel eğitim. [Children with special needs and special education.] Ankara: Eğiten Kitap [Egiten Book].

Baykoç-Dönmez, N. (2000, July). Special education in Turkey. Paper presented at the meeting of International Special Education Congress (ISEC), Manchester, UK.

Baykoç-Dönmez, N. (2011). Türkiye’de özel eğitim çalışmaları günümüzde yaşanan sorunlar ve çözüm önerileri. [Special education studies in Turkey current problems and proposed solutions]. In and N. Baykoç (Ed.), Özel gereksinimli çocuklar ve özel eğitim (pp. 535–556). [Children with special needs and special education.] Ankara: Eğiten Kitap [Egiten Book].

Baykoç-Dönmez, N., & Şahin, S. (2011). Özel eğitimin tarihi gelişimi [Historical development of special education]. In and N. Baykoç (Ed.), Özel gereksinimli çocuklar ve özel eğitim (pp. 535–556). [Children with special needs and special education.] Ankara: Eğiten Kitap [Egiten Book].

Cakiroglu, O., & Melekoğlu, M. A. (2013). Statistical trends and developments within inclusive education in Turkey. International Journal of Inclusive Education. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.836573

Cavkaytar, A., & Diken, İ. H. (2012). Özel eğitim 1: Özel eğitim ve özel eğitim gerektirenler. [Special education 1: Special education and those who require special education.] Ankara: Vize Yayıncılık [Vize Publication].

Children in Need of Protection Law [Korunmaya Muhtaç Çocuklar Hakkında Kanun], Government of Turkey. (1957).

Children with Special Education Needs Law [Özel Eğitime Muhtaç Çocuklar Kanunu], Government of Turkey. (1983).

Constitution of the Republic of Turkey. (1982). Retrieved from http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/anayasa.htm. Accessed on May 20, 2013.

Çuhadar, S. (2012). Özel eğitim süreci [Special education process]. In and S. Vuran (Ed.), Özel eğitim (pp. 3–30). [Special education.] Ankara: Maya Akademi [Maya Academy].

Diken, İ. H. (2010a). İlköğretimde kaynaştırma. [Inclusion in elementary school.] Ankara: Pegem Akademi [Pegem Academy].

Diken, İ. H. (2010b). Özel eğitime gereksinimi olan öğrenciler ve özel eğitim. [Students with special educational needs and special education.] Ankara: Pegem Akademi [Pegem Academy].

Diken, İ. H., & Batu, S. (2010). Kaynaştırmaya giriş. [Introduction to inclusion]. In and İ. H. Diken (Ed.), İlköğretimde kaynaştırma (pp. 1–25). [Inclusion in elementary school.] Ankara: Pegem Akademi [Pegem Academy].

Diken, İ. H., Cavkaytar, A., Batu, E. S., Bozkurt, F., & Kurtılmaz, Y. (2010). Effectiveness of the Turkish version of “first step to success program” in preventing antisocial behaviors. Education and Science, 36(161), 145–158.

Education of Gifted Children in the Fine Arts Law [Güzel Sanatlarda Fevkalade İstidat Gösteren Çocukların Devlet Tarafından Yetiştirilmesi Hakkında Kanun], Government of Turkey. (1956). Retrieved from http://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/ MevzuatMetin/1.3.6660.pdf. Accessed on May 20, 2013.

Elementary and Education Law [İlköğretim ve Eğitim Kanunu], Government of Turkey. (1961). Retrieved from http://mevzuat.meb.gov.tr/html/24.html. Accessed on May 20, 2013.

Employment Law [İş Kanunu], Government of Turkey. (1971). Retrieved from http://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.5.1475.pdf. Accessed on May 20, 2013.

Eripek, S. (2012). Zihinsel yetersizliği olan bireyler ve eğitimleri. [Individuals with intellectual disabilities and education.] Ankara: Eğiten Kitap [Egiten Book].

Er-Sabuncuoglu, M., & Diken, İ. H. (2010). Early childhood ıntervention in Turkey: Current situation, challenges and suggestions. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 2(2), 149–160.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, U.S.C. § 612 et seq.

Kauffman, J. M., Bruce, A., & Lloyd, J. W. (2012). Response to intervention (RTI) and students with emotional and behavioral disorders. In and J. P. Bakken, F. E. Obiakor, & A. F. Rotatori (Eds.), Behavioral disorders: Practice concerns and students with EBD (pp. 107–128). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Melekoğlu, M. A. (2013). Examining the impact of interaction project with students with special needs on development of positive attitude and awareness of general education teachers towards inclusion. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 13(2), 1053–1077.

Melekoğlu, M. A., Cakiroglu, O., & Malmgren, K. W. (2009). Special education in Turkey. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(3), 287–298.

Meral, B. F. (2011). Gelişimsel yetersizliği olan çocuk annelerinin aile yaşam kalitesi algılarının incelenmesi. [Examination of the family quality of life perceptions of mothers who have children with disabilities.] Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Anadolu Üniversitesi [Anadolu University], Eskişehir.

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (MEB) [Ministry of National Education]. (2003). Millî Eğitim sayısal veriler 2002–2003 [National education numerical data 2002–2003]. Retrieved from http://sgb.meb.gov.tr/istatistik/ist2002_ 2003.zip. Accessed on February 23, 2012.

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (MEB) [Ministry of National Education]. (2005). Milli Eğitim istatistikleri 2004–2005 [National education statistics 2004–2005]. Retrieved from http://sgb.meb.gov.tr/istatistik/ist2004-2005.rar. Accessed on February 23, 2012.

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (MEB) [Ministry of National Education]. (2006). Özel eğitim hizmetleri yönetmeliği. [Regulation of special education services.] Published in the Official Gazette of Republic of Turkey, Issue 26184, May 31, 2006.

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (MEB) [Ministry of National Education]. (2011a). Milli Eğitim istatistikleri örgün eğitim 2010–2011 [National education statistics formal education 2010–2011]. Retrieved from http://sgb.meb.gov.tr/istatistik/meb_istatistikleri_orgun_egitim_ 2010_2011.pdf. Accessed on September 6, 2011.

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (MEB) [Ministry of National Education]. (2011b). Özel eğitimle ilgili istatistiki bilgiler. [Statistical information about special education.] Obtained from the Ministry of National Education Strategy Development Presidency on a CD as an attachment to the official document dated September 30, 2011 and numbered 6543.

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (MEB) [Ministry of National Education]. (2013). Milli Eğitim istatistikleri örgün eğitim 2012–2013 [National education statistics formal education 2012–2013]. Retrieved from http://sgb.meb.gov.tr/istatistik/meb_istatistikleri_orgun_egitim_2012_2013.pdf. Accessed on May 12, 2013.

Özel Eğitim Arama Konferansı [Special Education Search Conference]. (2013). Anadolu Üniversitesi özel eğitim arama konferansı raporu, 16–17 Kasım 2013. [Anadolu University special education search conference report, 16–17 November 2013.] Arama Araştırma Organizasyon Danışmanlığı [Search Research Organization Counseling], Anadolu Üniversitesi, Eskişehir [Anadolu University, Eskisehir].

Özyürek, M. (2005). Öğrenme güçlüğü gösteren çocuklar. [Children with learning disabilities]. In and A. Ataman (Ed.), Özel gereksinimli çocuklar ve özel eğitime giriş (pp. 215–228). [Children with special needs and introduction to special education.] Ankara: Gündüz Eğitim ve Yayıncılık [Gunduz Education and Publication].

Rotatori, A. F., Obiakor, F. E., & Bakken, J. P. (Eds.). (2011). History of special education. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Şahin, S. (2005). Özel eğitimin tarihçesi. [History of special education]. In and A. Ataman (Ed.), Özel gereksinimli çocuklar ve özel eğitime giriş (pp. 49–70). [Children with special needs and introduction to special education.] Ankara: Gündüz Eğitim ve Yayıncılık [Gunduz Education and Publication].

Senel, H. G. (1998). Special education in Turkey. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 13(3), 254–261.

Special Education Law [Özel Eğitim Hakkında Kanun Hükmünde Kararname], Government of Turkey. (1997). Retrieved from http://orgm.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_ dosyalar/2012_10/10111011_ozel_egitim_kanun_hukmunda_kararname.pdf. Accessed on May 20, 2013.

Sucuoğlu, B., & Kargın, T. (2010). İlköğretim’de kaynaştırma uygulamaları. [Inclusion practices in elementary schools.] Ankara: Kök Yayıncılık [Kok Publication].

Turkish Civil Law [Türk Kanunu Medenisi], Government of Turkey. (1926).

Turkish Statistical Institute. (2012). Population and development indicators. Retrieved from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?tb_id=39& ust_id=11. Accessed on April 12, 2011.

Vuran, S., & Ünlü, E. (2012). Türkiye’de özel gereksinimli çocukların eğitimi ile ilgili örgütlenme ve mevzuat. [Organization and legislation about education of students with special needs in Turkey]. In and S. Vuran (Ed.), Özel eğitim (pp. 57–80). [Special education.] Ankara: Maya Akademi [Maya Academy].

World Bank. (2012). World development indicators database. Gross domestic product 2010. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GDP.pdf. Accessed on April 12, 2012.

Yıldırım Doğru, S. S. (2011). Erken çocuklukta özel eğitim. [Early childhood special education]. In and S. S. Yıldırım Doğru, & N. Durmuşoğlu Saltalı (Eds.), Erken çocukluk döneminde özel eğitim (pp. 37–102). [Special education in early childhood.] Ankara: Maya Akademi [Maya Academy].