SPECIAL EDUCATION TODAY IN BANGLADESH

Md. Saiful Malak

ABSTRACT

This chapter provides a comprehensive description of special education in Bangladesh. It begins with the early origins of special education and then proceeds with definitions of and prevalence of current disabilities in Bangladesh. This section is followed by governmental policies and legislation related to the right to education for all students with disabilities. Next, educational intervention methods are delineated along with a description of governmental special schools and teacher training and preparation of special educational professions. Early intervention practices and working with families is also discussed. The chapter ends with the progress that Bangladesh has made and the challenges that remain.

INTRODUCTION

As one of the most densely populated countries of the world, Bangladesh is distinct in terms of its language liberation, religious values, and customs. With a population of over 164 million, this country has made significant progress toward achieving the Education for All (EFA) goals during the past decade (World Bank, 2008). The net enrollment rate at primary level has increased from 87.2% in 2005 to 98.7% in 2012 (Directorate of Primary Education [DPE], 2012). The gross and net enrollment rates are increasing steadily (Miles, Fefoame, Mulligan, & Haque, 2012). However, the perspective of education for students with disabilities provides a different story. Only 4% of an estimated 1.6 million school-going age children with disabilities attend a range of schools including nonformal, special, integrated, and inclusive settings (Disability Rights Watch Group Bangladesh, 2009, p. 4). Interestingly, the literature suggests that Bangladesh has enacted a good number of policies and legislation regarding educational placement of children with disabilities (Ahsan & Burnip, 2007; Ahsan & Mullick, 2013). Moreover this country is a signatory of world’s most prominent treaties including United Nations Conventions on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – 2006 (Ahsan, Sharma, & Deppeler, 2012) in which education of children with disabilities is to be implemented through inclusive education. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the situation of children with disabilities that might be a concern to the Department of Education in Bangladesh. Based on descriptive review, this chapter critically analyzes the development, progress, and challenges of special education in the context of Bangladesh. More importantly, it explores the prospects of inclusion of students with disabilities into regular education.

ORIGIN OF SPECIAL EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH

The origin of special education in Bangladesh seems to have been limited to the discipline of psychology. As a separate discipline, psychology was taught in very few institutes during the 1960s. A group of psychologists formed Bangladesh Psychological Association (BPA) in 1970. Gradually, a wing of BPA started growing interest in clinical psychology which turned into Bangladesh Mental Health Association in early 1980s. During 1970s–1980s, Professor Sultana Sarwatara Zaman with her dynamic initiative formed an organization named Society for the Care and Education of the Mentally Retarded – Bangladesh (SCEMRB), for the welfare of children and young adults with mental retardation. The organization comprised of a group of professionals, social workers, and parents of mentally retarded children, when most of the people of this country had diminutive knowledge and concept about social and educational aspects for this segment of population. With the advent of time, the terminology to address children with mental retardation have revolutionized that led later to rename the organization as the Society for the Welfare of Intellectually Disabled – Bangladesh (SWID-BD). Presently, SWID has approximately 51 branches all over Bangladesh (Rahman, 2011).

As a pioneer in the arena of special education, Professor Zaman devoted a lot of time and contribution to uphold the status of children with intellectual disability through raising mass awareness on disability, when there were misconceptions and superstitions about disability issues among most of the communities in Bangladesh (Kibria, 2005; Miles & Hossain, 1999). With time this self-motivated professor along with her associates has realized the necessity to expand her activities in a broader perspective. These expansions led the way to establish a similar organization with new innovations (Zaman & Munir, 1992). Giving emphasis on teacher preparation and research on special education, Professor Zaman established the “Bangladesh Protibondhi (disabled) Foundation (BPF)” in 1984 (Zaman & Munir, 1992) through which she continued her interest on the care, education, and research for children and young adults with intellectual disability in Bangladesh. Her continuous interest, advocacy, and work on teacher development helped develop courses and degree programs for special education teachers (Rahman, 2011). In the early 1990s, the Institute of Education and Research (IER) at the University of Dhaka revised its teacher education curriculum and established the Department of Special Education within the preview of the institute. A number of degrees in special education, including Diploma in Education (Dip-in-Ed), Bachelor of Education (BEd)-Honors, and Master of Education (MEd) with specialization in intellectual disability, hearing impairment, and visual impairment were started at the University of Dhaka. Further, after the establishment of the Department of Special Education, the scope of conducting small scale research on special education and disability studies was formally created at the University of Dhaka. As a result, various research works and psychological assessment services in the late 1990s led to the development of psychometric assessment tools and technologies in the context of Bangladesh (Rahman, 2011).

The decades of 1990s and 2000s were remarkable in the field of special education in the context of Bangladesh (Miles et al., 2012) for several reasons. First, the establishment of the Department of Special Education had created the opportunity for prospective teachers to be skilled in teaching children with disabilities. A good number of people, mostly parents of children with disabilities, showed their interests in opening special schools. Accordingly, several special schools were established in city areas and parental interests on sending their children with disabilities to special schools significantly increased. During the mid-1990s, several pressure groups (e.g., Parent Association, Special Teacher Association) were formed and special education had widely been recognized in the nongovernment sector in Bangladesh. Second, the growing interest of special education in nongovernment organizations (NGOs) had gradually been recognized by the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) and a National Policy on Disability was formed in 1995. This policy was the first initiative by GoB on disability in the context of Bangladesh. Since 1995, various pressure groups were involved in advocacy with different levels of GoB toward getting a complete legislation regarding persons with disabilities. Finally, in 2001, the people of Bangladesh received their first legislation entitled “Bangladesh Persons with Disability Act, 2001.” As a result, education for children with disabilities has become obligatory to the GoB and special education has been included in the government’s reform agendas.

DEFINITION OF DISABILITY

There are variations in terminologies used in the area of disability among academics, human right activists, NGO professionals, and government officials working on disability issues. According to Bangladesh Persons with Disability Act, 2001 (Ministry of Social Welfare [MoSW], 2001), “disability” is defined by the GoB as follows:

Disability means any person who is physically crippled either congenitally or as result of disease or being a victim of accident, or due to improper or maltreatment or for any other reasons became physically incapacitated or mentally imbalanced, and as a result of such crippledness or mental impairedness, has become incapacitated, either partially or fully; and is unable to lead a normal life. (MoSW, 2001, p. 5)

Over the past decade, this definition has widely been criticized by academics and human right activists as they tend to view that disability has been seen through the lens of Medical Model (e.g., see Kibria, 2005; Šiška & Habib, 2013). Although the majority of the stakeholders, including social workers, academics, human right activists, and the persons with disabilities themselves are more likely to consider disability from the perspective Social Model, their consideration seems to have little impact on the GoB’s initiatives regarding disability (National Forum of Organizations Working with Disabled [NFOWD], 2009). Various pressure groups, in collaboration with NFOWD, continued to work with the GoB with an intention to revise the Bangladesh Persons with Disability Welfare (BPDW) Act, 2001. Consequently after a decade a relatively more comprehensive definition of disability with its various types has been provided by the GoB through the most recent legislation called “Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2013” (MoSW, 2013). Under this Act, disability is defined as follows which seems to capture more social aspects than medical condition:

“Disability” means any person who, by any reason acquires long-term or short term physical, mental, developmental or sensory problem that might create a negative attitude and environmental barrier for that individual and which can lead an individual not to achieve his equal rights to have an independent and effective participation in the society. (MoSW, 2013, p. 3)

TYPES OF DISABILITY

There has been a little change in the types of disability between 2001 and 2013 (Table 1). Autism and deaf-blindness have been added, cerebral palsy has been separated from physical impairment, and a distinction between mental illness and intellectual disability has been established through the Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2013.

Table 1. Types of Person with Disabilities.

| 2001: Bangladesh Persons with Disability Welfare Act |

2013: Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act |

| – |

Autism |

| Physical handicap |

Physical disability |

| – |

Mental illness leading to disability |

| Visual impairment |

Visual disability |

| Speech impairment |

Speech disability |

| Mental disability |

Intellectual disability |

| Hearing impairment |

Hearing disability |

| – |

Deaf-blindness |

| – |

Cerebral palsy |

| Multiple disabilities |

Multiple disabilities |

PREVALENCE OF DISABILITY

Over the past several decades, the prevalence of persons with special needs in Bangladesh has been an issue of debate due to lack of national statistics. The Bangladesh Bureau of statistics (BBS) is the only responsible organization to provide national data about the population of Bangladesh. It runs the national census called population and housing census (PHC) every decade. There is no provision of gathering data nationally about the population rather than the PHC. Persons with disabilities had always been ignored during the first, second, and third censuses which took place in 1974 (could not take place in 1971 due to liberation war), 1981, and 1991 respectively. The disability population issue was planned to be addressed for the first time in the 4th census in 2001. However, the result created a huge contradiction about the number of persons with disability identified. Persons with disabilities counted in the 4th census were 0.6% of the total population (National Foundation of Disabled Development (NFDD), 2013, p. 105) which seems to be a faulty estimation.

The national census scheduled in the early part of 2011 was planned to address the above issue in a detailed manner. This census was supposed to give the GoB a detailed statistics on persons with disabilities, disaggregated by: the 14 types of disability; age; gender; ethnic origin; and urban/rural strata. It was anticipated that this census would give an opportunity to address further statistics on their progress toward accessing rights issues.

Organizations working for persons with disabilities have rejected the findings of the 5th PHC-2011, saying that it undercounted the people belonging to this group. According to the census findings launched, 1.4% of the total population belongs to people with disabilities. The number of people with disabilities has been cited as 2,016,612 (NFDD, 2013, p. 105) which was far below the 2011 estimation of Household Income Expenditure Survey of the BBS that reported people with disability at 9.07% (BBS, 2011). It is widely claimed that the questionnaires used for the census could only identify those individuals who had severe disabilities that were visible to all. Most recently, Action AID Bangladesh (AAB) conducted a number of baseline surveys in various locations in Bangladesh. Based on AAB, Ahsan (2013, p. 3) reported that the overall prevalence rates of disability is around 14.4%. Even through there is no accurate statistics on the number of children and adults with disabilities in Bangladesh, most people rely on the data found in various sources that suggest that 10% of the people in Bangladesh have disabilities (United Nations, 2006; World Health Organization [WHO], 2006).

Disability Type and Prevalence

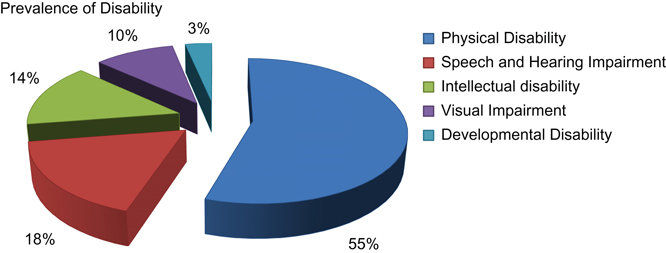

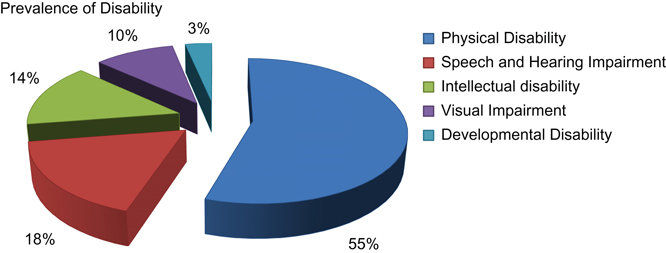

Since there is no reliable national data of persons with disabilities in Bangladesh, the prevalence of disability according to type is less likely to be shown. However, within the context of Bangladesh, there a number of sources which could provide an impression about how the prevalence would look like based on the type of disability. For example, a study jointly conducted by the DPE and Center for Services and Information on Disability (CSID) (2002) to explore the education status of children with disabilities in 12 districts in 6 divisions of Bangladesh collected data from 360 children with disabilities. This study reported that among the participants the majority (50%) had physical disability which was followed by speech and hearing impairment (16%), intellectual disability (13%), visual impairment (9%), multiple disabilities (9%), and other (3%) developmental disabilities (Fig. 1).

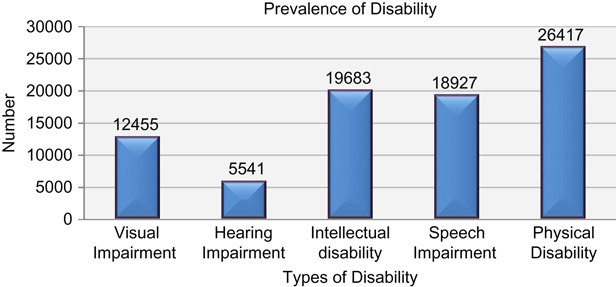

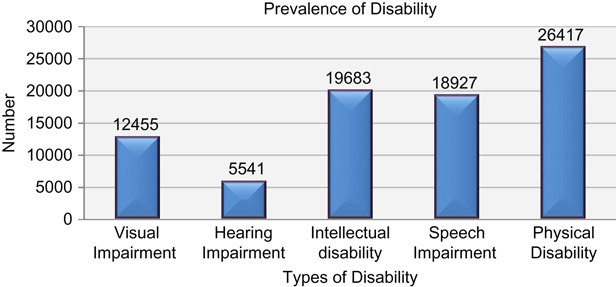

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA, 2002) conducted a study on 2,559,222 children with disabilities aged between 3 and 10 years. This study reported that physical disabilities showed the highest incidence (41.5%) followed by visual impairments (19.7%), speech and hearing impairment (19.6%), intellectual disabilities (7.4%), cerebral palsy (7%), multiple disabilities (3.4%), and mental illness (1.4%) (JICA, 2002, p. 47). Lastly, a recent Primary School Census 2010 conducted by the DPE (2011) identified 83,023 children having disabilities. The census also showed that the type of children with disabilities enrolled in primary education are visually impaired (12,455), hearing impaired (5,541), intellectually challenged (19,683), speech problem (18,927), and physically challenged (26,417) (Fig. 2).

This is important to note none of the studies mentioned above included children with autism as separate type of disability although it is said that there has been a significant increase in the number of children with autism in recent years in Bangladesh.

Fig. 1. Prevalence According to Type of Disability.

Fig. 2. Disability Prevalence in Primary Education.

POLICY AND LEGISLATION

During the past three decades, disability has been treated as a charitable issue in Bangladesh. The Department of Education, which comprises the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME) and Ministry of Education (MoE), is responsible to provide education for all children across the country. However, “the education of children with disabilities, as well as issues related to disability, is under the purview of the MoSW, and thus looked upon as a charity or welfare, not as a human rights issue” (Munir & Zaman, 2009, p. 292). Therefore, the right of persons with disabilities in Bangladesh seems to remain segregated from mainstream policy though it is protected by the constitution.

The need for education for all children, regardless of any special circumstances, has been echoed from the birth of this country through its constitution in 1972. Articles 17 and 28 of the constitution clearly articulated how the state should provide education to all children without making any discrimination.

[Article 28 (3)]: No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth be subjected to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to access to any place of public entertainment or resort, or admission to any educational institution. (Ministry of Law Justice and Parliamentary Affairs [MoLJPA], 2000, p. 5)

[Article 17 (a)] … establishing a uniform, mass oriented and universal system of education and extending free and compulsory education to all children to such stage as may be determined by law. (MoLJPA, 2000, p. 8)

Despite the strong constitutional ground, lack of knowledge and awareness regarding disability remains one of key challenges to enacting a complete legislation for persons with disabilities in Bangladesh. As mentioned earlier, there is a large group of NGOs working for persons with disabilities across the country. NFOWD, claiming to be the parent organization of those NGOs, is considered as one of the vital advocacy groups providing the government with comprehensive guidelines necessary for persons with disabilities (Miles et al., 2012).

Working in collaboration with the government, local NGOs, and academic groups (University academics and researchers), NFOWD and other organizations have prioritized efforts to promote persons with disabilities through various activities including organizing national seminars and symposiums, celebrating National and International Days for persons with disabilities, and providing legislative support for persons with disabilities. Due to increasing exposer and supports of various advocacy groups to the government, the GoB has enacted the very first policy called the “National Policy on Persons with Disabilities” in 1995. Since 1995, there has been an increased emphasis on enacting a comprehensive legislation for persons with disabilities. Additionally, over the past 20 years, Bangladesh has been keen to show positive attitudes toward various international declarations, conventions, and commitments regarding persons with disabilities. Like many other countries around the world, Bangladesh has agreed with the declaration of Education for All (EFA) (UNESCO, 1990), the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994), and the Dakar Framework for Action (UNESCO, 2000). Agreeing with all the international treaties, Bangladesh has committed to address education for children with disabilities within the existing education system.

After three decades of continuous advocacy of various pressure groups and significant influence of several international treaties, the GoB enacted its first legislation regarding persons with disabilities in 2001. Although there were numerous gaps in terms of terminologies and definitions of the BPDW Act, 2001, it has opened the door of establishing rights of persons with disabilities in the context of Bangladesh. The following section describes major policies and legislation regarding persons with disabilities enacted in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh Persons with Disability Welfare Act, 2001

BPDW Act covers different aspects of persons with disabilities including definition, education, health care, employment, transport facilities, social security, and so on. Particularly, in education, this Act has been recognized as the very first initiative to ensure education as a legislative right for children with disabilities. The Act postulates:

Create opportunities for free education to all children with disabilities below 18 years of age and provides them books and equipment free of cost or at low-cost (Part D: 2). (MoSW, 2001)

In the third section, the Act calls for creating opportunity for the children with disability to study in the mainstream education.

Endeavor to create opportunities for integration of students with disabilities in the usual class-set-up of regular normal schools wherever possible. (MoSW, 2001, p. 12)

Despite having several important guidelines for students with disabilities, the Act itself can be considered as a barrier to inclusive education. First of all, this Act seems to lean on the medical model of disability (Šiška & Habib, 2013). For example, the definition of a person with disabilities is articulated on the basis of clinical feature of the individual. For instance, a person with visual impairment is referred to as “No vision in any single eye or in both eyes, or visual acuity not exceeding 6/60 or 20/200 …” (MoSW, 2001, p. 5).

Also, Part D (1) of this Act suggests segregated education for children with disabilities

… establishment of Specialized Education Institutions to cater to the special needs of the special categories of children with disabilities, to design and develop specialized curriculum and write special text books and to introduce Special Examination System, if situations so demand. (MoSW, 2001, p. 11)

Since the Act has been enacted from medical and charity point of view, it remains weak to articulate equal educational setting for the children with disabilities. It is also noted that this Act has been initiated by the MoSW instead of MoE or Law Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. It implies that disability has been perceived as charity by policy makers (Šiška & Habib, 2013). It can be argued that due to the welfare attitudes toward disability, the education of students with disabilities have not been considered as a right. As a result, inclusive education has not been stated clearly through this Act.

National Education Policy (NEP) 2010

The NEP 2010 (MoE, 2010) was formally approved by the Parliament of Bangladesh in December 2010. It is worthy to mention that NEP 2010 was revised, modified, and finalized from the very first version available in 2000. This policy is another official commitment of the government toward inclusive education. In its foreword, the Minister of Education underscored that ensuring quality education for all children is a fundamental issue (MoE, 2010, p. vi). The NEP 2010 calls for every child to be educated. The NEP highlights the education for diverse learners within its main objectives as follows:

07: Eliminate discriminations on grounds of nationality, religion, class and gender; build up an environment that promotes secularism, global-brotherhood, and empathy towards humanity and respect towards human rights.

22: Bringing all socio-economically disadvantaged children into education including street-children.

24: Ensuring the rights of all children with disabilities.MoE, 2010, pp. 1–2

Further, a number of statements described in the NEP 2010 documents relate to quality and inclusive education facets. Table 2 displays the summary of major statements relevant to learners with disabilities for both primary and secondary education sectors.

Table 2. Key Statements of National Education Policy 2010 Regarding Disability.

| Chapter |

Themes |

Summary of Key Policy Statements |

| 2 |

Preprimary and Primary Education |

Ensure equal opportunities for all kinds of disabled and underprivileged children |

| 4 |

Secondary Education |

Alleviate discriminations among various socioeconomic, ethnic, and socially disadvantaged children |

| 18 |

Education for challenged learners (special education) |

• Include handicapped students in the mainstream education |

| |

|

• Provide special education to acutely handicapped children with physical or mental disability |

| 24 |

Teachers’ Training |

• Increase teachers’ efficiency in using strategies for educational innovation |

| |

|

• Encourage teachers to teach all students irrespective of religion, race, and socioeconomic conditions maintaining equal opportunities |

| |

|

• Assist teachers to acquire efficiency to deliver lessons to students from disadvantaged and ethnic community and disabled learners by considering their special (learning) needs |

Note: The statements are summarized in case of very long sentences.

Despite the fact that the NEP 2010 has mainstreamed the educational rights of children with disabilities, it is likely to create a debate among people working for children with disabilities as none of the policy statements directly uses the term inclusion or inclusive education. Critical analysis of the policy statements suggests that most of the statements are broad and often unclear in indicating specific meaning. The policy comprises a number of sections that underpin education for all children, but it is not clarified in the policy whether children with disabilities will get access to the same school with their regular peers. Instead, in some statements, “special education provision” is suggested for the education of the children with special needs. For example, section 18 (7) states – “Separate schools will be established according to special needs and in view of the differential nature of disabilities of the challenged children” (MoE, 2010, p. 43). Some vocabularies clearly contradict with the philosophy of inclusion. For example, in Chapter 18, the words “handicapped,” “dumb,” etc. are used to describe the children with special needs. This reflects an attitude (of policy makers) that is aligned with segregation rather than inclusion. This is rather contradictory to the notion of inclusive education. Therefore, education reform based on policy statements such as the above may reduce the effective implementation of inclusion at the school level of Bangladesh.

Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2013

Since 2001, there has been increased emphasis on the revision of the Bangladesh Persons with Disability Welfare Act. Consequently the Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2013 was enacted as a revised version of the previous Act. Various important sections under the present Act seem to be more comprehensive in terms of definition, clarification, and implementation guideline. A summary of this Act is presented in Table 3.

One of the significant aspects of this Act is that it clearly states that children with disabilities cannot be denied from their enrollment in regular schools (MoSW, 2013). In Article 15, this Act provides a clear description on how people can be aware of the ability and potential of persons with disabilities. It states that “In order to develop positive attitudes towards persons with disabilities from childhood, relevant contents about children with disabilities should be included in the curriculum of all levels of education” (MoSW, 2013, p. 10).

Table 3. Key Information of Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2013.

| Article |

Themes |

Summary of Key Policy Statements |

| 1 |

Detection |

• Conduct national survey for collecting data about persons with disabilities |

| |

|

• Include necessary instrument in all national level surveys including human census for identification of persons with disabilities |

| |

|

• Develop a national database on persons with disabilities |

| 5 |

Accessibility |

Use IT for making textbooks prepared by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) accessible for children with disabilities |

| 9 |

Education and training |

• Provide flexibility in admission to children with disabilities regarding their age |

| |

|

• Ensure reasonable accommodation and joyful environment for children with disabilities in order to facilitate inclusive education for all children |

| |

|

• Take necessary steps to integrate specialized educational institutes with regular schools |

| 12 |

Freedom from violence, access to justice, and legal aid |

Protect persons with disabilities from any kinds of abuse and violence and provide them with administrative, legal, social, educational, and other necessary support |

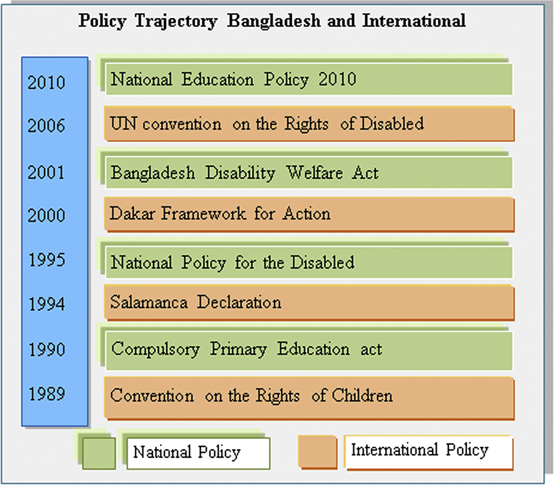

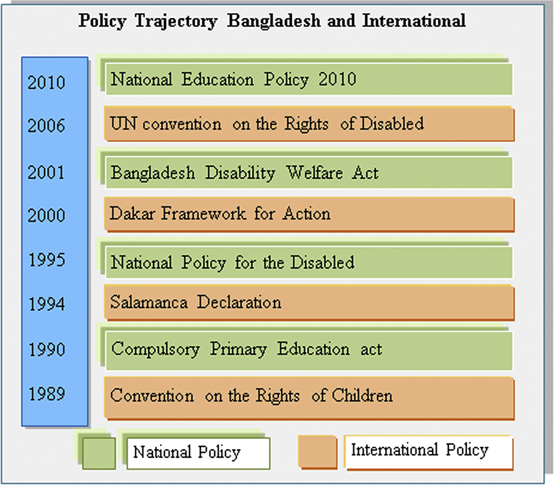

It is claimed that Bangladesh has undertaken a good number of policy initiatives to provide equity and access to education for all children (Ahsan & Burnip, 2007). However, it is important to note that the trend of enacting inclusive (IE) policy and legislation in Bangladesh is mainly based upon the international treaties (Malak, Begum, Habib, Banu, & Roshid, 2014).Fig. 3 shows how Bangladesh government endorsed disability-related policy and legislation soon after signing an international treaty.

Fig. 3. Policy Initiatives of Bangladesh.

Fig. 3 shows that IE initiatives in Bangladesh have been embedded in different policy and legislations, including Compulsory Primary Education Act, 1990;National Education Policy for the Disabled, 1995; BPDW Act, 2001; and NEP, 2010.

EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTIONS

Over the period of 1970s–1990s, students with disabilities were segregated from the mainstream education in Bangladesh as disability issues seemed to be less focused on government’s main reform agendas. Special schools, though inadequate in number, were the only option for educating students with disabilities. However, in recent years, Bangladesh has become a cosigner of all international treaties regarding education and disabilities such as the Education for All declaration (UNESCO, 1990), the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994), the Dakar Framework for Action (UNESCO, 2000), and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 in which education for children with disabilities is likely to be provided through an inclusive framework. As a result, inclusive education has been an area of focus for both government and nongovernment agencies.

During the past decade, the GoB has been keen to practice inclusive education through undertaking various programs. Two major programs namely Primary Education Development Program (PEDP) and Teaching Quality Improvement in Secondary Education (TQI-SEP) are considered to be the most important interventions to implement inclusive education in regular schools. The following section describes how inclusive education has been practiced in educational settings through these programs.

Primary Education Development Program

PEDP is an umbrella program of Bangladesh government to enhance primary education. The first program (1997–2003) focused on the gross enrollment rate in primary education. However, the second program (2004–2011) incorporated a specific component on inclusive education to address diversity in the regular school system. The inclusive education component included four specific target groups: gender, children with disabilities, children from ethnic background, and children from vulnerable group (e.g., slum children, refugee children, street children, orphans, children from ultra-poor families) to bring them into regular classrooms. The second PEDP was a massive training program for teachers, head teachers, and local education administrators on inclusive education.

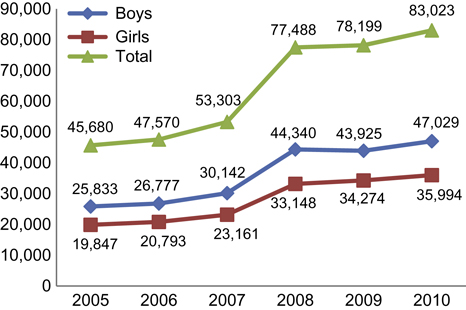

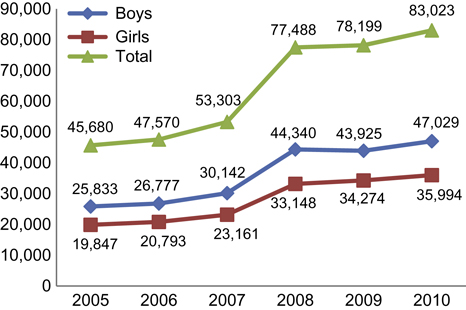

Studies indicated that the second PEDP made important strides forward in terms of inclusion of students with disabilities during its early years (Ahuja & Ibrahim, 2006; Nasreen & Tate, 2007). Under the second PEDP, a formal declaration was made by the DPE that students with disabilities would not be denied enrollment from regular school. This declaration was the first government initiative to provisionally ensure the admission of students with disabilities in regular schools. BANBEIS (2011) has documented the enrollment figures of children with disabilities for six consecutive years (from 2005 to 2010) (see Fig. 4). The figure clearly shows that the number of enrolled children with disabilities has nearly doubled in a five-year duration.

The baseline survey conducted in 2005 revealed that 45,680 children with disabilities were accommodated in primary schools and among them a significant number of students were with intellectual disabilities (PEDP Completion Report, 2011; DPE, 2011). The enrollment of special needs children increased by 5% each year (DPE, 2010). However, the exact number of school-aged children with disabilities has not been reported yet. While Fig. 4 shows an increased trend in children with disabilities enrollment, the proportion of the total enrollment number of school-aged children with disabilities could not be computed due to the noted gap absences.

Fig. 4. Trend in Enrollment of Children with Disability at Primary Level.

The second PEDP provided improved basic education to children in remote areas, and infrastructure facilities (e.g., by providing ramps, modifying classroom furniture to increase the access for children having disabilities). However, recent studies report that infrastructural development has not been reached its set target (DPE, 2012) and teachers have demonstrated disappointments on inadequate classroom facilities for practicing inclusive education (Malak, 2013a).

In addition to improving infrastructure, the role of SMC is consistently suggested as a major support for implementing inclusive education at schools. However, though it is claimed that massive training has been provided by the second PEDP, studies (Malak, 2013b; Mullick, Deppeler, & Sharma, 2012) found that due to the lack of awareness of teachers and school administrators regarding disability, the implementation of inclusive education is facing numerous challenges. In order to address the challenges PEDP has been extended for the third time in 2011. One of the important aims of the third PEDP is to ensure inclusive education practice through empowering school community.

Teaching Quality Improvement in Secondary Education

In order to enhance quality of secondary education, the GoB has undertaken a number of initiatives. TQI-SEP (Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education (DSHE), 2005) was one of the initiatives to address the equity, inclusion, and quality aspects in the secondary education of Bangladesh. This project was jointly funded by the GoB, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). It was formally launched in 2005 and closed in 2012. The DSHE worked as the implementing agency (Project Management Unit) under the purview of the MoE along with the project’s two partner organizations, namely, the National University and the National Academy for Educational Management (NAEM).

Improving teacher training facilities, strengthening in-service and preservice teacher training, and increasing equitable access and improving community involvement were the key areas of intervention under TQI-SEP (DSHE, 2005). As part of the broader goal of achieving quality secondary education in Bangladesh, the project adopted substantial measures for the implementation of inclusive education. The main goal of the project was strengthening the provisions/opportunities for equitable access of all eligible children (with primary completion) in the secondary classrooms and underpinning their participation in all relevant activities within the school or classroom setting. In believing that teachers play the most important role in enhancing students’ learning (ADB, 2004), the project involved strategic planning for teachers to assist them in the development of necessary knowledge and inclusive teaching practices skills that would empower them to create a learner-friendly environment which in turn would allow effective learning for all children regardless of disability, gender, geographical location, and ethnicity (DSHE, 2007).

The above project’s philosophy was that teacher professional learning was seen as a comprehensive part of a total inclusive environment. In addition to professional learning opportunities, the project plan included a range of supportive activities to enhance the implementation of inclusive education in a real classroom setting. These supporting activities included the following: improving the physical facilities (to remove the barrier to physical movement), modifying teachers’ education curriculum, and introducing continuous professional development (CPD). The project’s activities not only strengthened the classroom teacher’s skills but enhanced the provisions for inclusive practice.

A number of reform activities were undertaken in TQI-SEP to enhance inclusive practice in the secondary education sector. The major activities of this project included: strengthening school capacity to provide effective learning environment for all children including children with disabilities; inclusive education awareness raising program for head teachers and members of school management committee; awareness raising program for district level officers (District Education Officers, DEO); inclusive education orientation program for teacher educators from Teacher Training Colleges (TTCs) and relevant NGO representatives and professional development programs for secondary in-service teachers. Under TQI-SEP numerous teacher training activities have been performed. Malak et al. (2014) reported that 195,000 teachers have taken the first CPD program which comprised a series of three programs to use participatory and inclusive approaches in the classroom, instead of rote learning. Included in the above teacher training program where 1,650 teachers from three outreach districts.

Despite the above adequate teacher training initiatives, TQI-SEP has been criticized as having little impact of training activities in real settings. Studies by Khan (2012) and Rahaman and Sutherland (2012) demonstrated that secondary teachers in Bangladesh have shown inadequate understanding and a variety of interpretations of the IE concept. According to Khan, teachers’ understanding IE is fairly vague and broader rather than focused and specific. As a result, Rahman and Sutherland indicated that teachers do not adequately take the responsibility of facilitating learning for all students including those with disabilities. Khan considered insufficient teacher professional learning opportunities as a dominant negative issue in ways to implement IE at the secondary level. Furthermore, the literature suggests that the lack of good quality professional development is a significant barrier for empowering secondary teachers with inclusive instructional knowledge and skills in Bangladesh (Malak et al., 2014). Evidence suggests that engaging classroom teachers in high quality professional development is an inherent aspect for the effectiveness of inclusive practices (OECD, 2005).

Thus, the TQI-SEP professional development activities have created some awareness or enthusiasm about inclusion among the secondary teachers. However, the practice of inclusion in teachers’ classroom instruction is far from completion. Because of this, the first TQI-SEP was extended for another five years in 2012. A major component will be to address inclusive education and gender friendly environment in secondary education classrooms.

Generally, students with disabilities have little access to regular schooling in developing countries. The literature suggests that there is only 1 or 2% of students with disabilities that go to regular schools in South Asian countries (USAID, 2005). Unexceptionally in Bangladesh, access of students with disabilities to regular schooling is negligible. Although the above mentioned interventions, PEDP and TQI-SEP, seem to be an influential effort from the GoB to facilitate inclusive education, it is likely that the majority of students with disabilities are still segregated from nondisabled peers in regular schools. As a result, special education is predominant for children with disabilities in Bangladesh. The following section describes how students with various types of disabilities are taught in the context of Bangladesh:

Special Schools Run by the Government of Bangladesh

Opportunity to attend a special government school for children with disabilities is extremely limited in Bangladesh (USAID, 2005). If fact, there are only 13 government managed special schools in Bangladesh. The schools are for four categories of children with disabilities, namely, visual impairment, hearing impairment, intellectual disability, and autism (NFDD, 2013). The following sections describe these special categorical schools.

Schools for Students with Visual Impairment

There are four schools for students with visual impairment at the primary level with a capacity to serve 500 students. The schools are located in four geographic regions, namely, Dhaka, Rajshahi, Khulna, and Chittagong. Of the total number of students, 180 students are provided residential facilities.

There are 64 government-funded integrated secondary schools for students with visual impairment in 64 districts. A resource teacher, trained in visual impairment, is appointed in every integrated school. While the function of these integrated schools is thoroughly described in government documents, the reality of their functions is unclear.

Schools for Students with Hearing Impairment

There are seven government-sponsored special schools for students with hearing impairment. These schools have a capacity to facilitate special schooling for 700 students of which 180 students receive residential facilities.

Schools for Students with Intellectual Disability

Access of children with intellectual disability to schooling is extremely limited. There is no government school for these children. However, due to continuous advocacy of several NGOs working with children with intellectual disabilities, including the SWID-Bangladesh and BPF, the MoSW introduced an Integrated Special Education Policy, 2009 for providing educational access to children with intellectual disabilities. Under this policy, 48 special schools of SWID-Bangladesh and 7 inclusive schools of BPF have been receiving government fund for their teachers since 2010. A total of 463 teachers from SWID-Bangladesh and 75 teachers from BPF are receiving 100% of their salary on behalf of the government through the MoSW (NFDD, 2013).

Schools for Children with Autism

Autism as a separate category disability has been recognized very recently in the context of Bangladesh. In July 2011, Autism Speaks (an NGO), in collaboration with the GoB and World Health Organization, organized an International Conference on Autism and Developmental Disabilities in Dhaka where over 1,000 delegates from 11 countries attended. This conference has had a huge impact on both government and nongovernment agencies working with disabilities. Consequently, the MoSW, under the NFDD has introduced a resource center for children with autism which provides special education, therapy and referral services, and counseling to autistic children and their parents. A group of experts consisting of psychologist, occupational therapist, and speech and language therapist are working in this center (NFDD, 2013).

Under the patronization of the MoSW, the NFDD has opened the Autistic School in 2011. Autistic children of poor families are entitled to study in this special school free of cost. A group of specially trained teachers have been imparting special education in this school. This government-sponsored school can provide special schooling for up to 50 children with autism (NFDD, 2013).

Schools for Children with Physical Disabilities

There are no specially designed educational services for children who are physically challenged. There are several reasons behind this, including inaccessible buildings, lack of appropriate handicapped toilet facilities, mobility aids such as crutches and wheelchairs, and appropriate curriculum and instructional materials (USAID, 2005).

EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES PROVIDED BY LOCAL NGOS

It is worthwhile to note that apart from the above mentioned government facilities, a good number of NGOs have been working with children with disabilities in Bangladesh. A contemporary report of MoSW shows that there are more than 600 NGOs that work with children with disabilities in 64 districts (MoSW, 2012, p. 78). These NGOs are providing education for children with disabilities in various forms including special education, integrated education, and inclusive education. A few of the reputed NGOs working in the area of education for children with disabilities in Bangladesh include the following: HI-CARE provides primary and secondary education for children with hearing impairment and preschooling for 2 to 5-year-old children; The Baptist Sangha Blind School, which was established in 1977, works in 64 districts through a variety of activities including vocational training for children with visual impairment, integrated education, computerized Braille book production, residential facilities are available for visually impaired girls and a source of technical assistance for orientation and mobility, Braille translators, special teaching techniques, and vocational training for students with visual impairment; The Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation (BPF), which was established in 1984, serves children with intellectual disability and children with neurological damage (e.g., cerebral palsy) in eight urban poor subdistricts and runs a special school for children with intellectual disability while providing variety of screening and diagnosis services for young children; The Center for Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed (CRP) is widely recognized as a pioneer organization for rehabilitation of persons with physical disability in Bangladesh which runs an inclusive school, established in 1993 mainly for children with cerebral palsy. It also provides training for special education teachers and community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers; Autism Welfare Foundation (AWF) is a relatively new NGO founded by a mother of an autistic child, which serves children aged 3–15 years with home-based educational intervention for children and supports high-functioning children who are in mainstream education programs; Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) operates 35,000 schools in Bangladesh and provides basic education to young learners through its education program (World Bank, 2008). Recently, BRAC has started including three children with disabilities in each of its existing schools (Mahbub, 2008). Lastly, there are a number of international organizations which have been playing key roles in Bangladesh to facilitate schooling for children with disabilities such as Plan, Sight Severs, and Action-Aid.

USE OF TECHNOLOGY FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES

The use of appropriate technology in education could have enormous impact on the learning of children with disabilities. While a variety of assistive and educational technologies are recognized as the key elements for promoting children with disabilities, the availability of such technologies seems to be minimal in the context of Bangladesh (USAID, 2005). Huq (2005) argued that the government agencies had little understanding of technological development for children with disabilities. Accordingly, government’s effort to arrange assistive and educational technology for children with disabilities is less likely to meet the actual demand (USAID, 2005). Generally, it is only those children who have parents with means who can get access technology in Bangladesh. However, there are some NGOs that arrange different types of low-cost assistive and educational technology for children with disabilities. For example, HI-CARE provides low-cost hearing aids for children with hearing impairment. There are also quite a few local NGOs which provide low-cost hearing aids for children across the country. Also, Braille materials are provided by Baptist Sangha Blind School. Additionally, learning materials for low vision children are provided by Sight Severs Bangladesh and a low vision laboratory has been established at the University of Dhaka to help preservice special education teachers conduct research on developing low-cost teaching materials within the context of Bangladesh. Also, the Department of Special Education of the University of Dhaka with the financial support from Center for Disability in Development (CDD) has developed a sign language in 2003, called Sign Supported Bangla Language (SSBL). The BPF has played a leading role in developing an Augmentative Communication system for children with intellectual disabilities and for those with cerebral palsy. Several special schools in the capital city of Dhaka are using Augmentative Communication system for improvement of their students. Further, worldwide Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is recognized as one of the most effective tools for responding to children with autism and several NGOs including Proyash and AWF have conducted a number of workshops on ABA.

EARLY INTERVENTION PROGRAMS

Early intervention program seems to be a common component for majority of NGOs working in disability in Bangladesh. The primary focus of most of the early intervention programs in the context of Bangladesh is on screening and assessment of disability and referral for services (Sultana, 2010). School- and home-based therapeutic services are also provided by a number of NGOs while a few of them emphasize on preparation for regular schooling as part of their early intervention programs.

Realizing the benefit of early intervention programs in child development, the GoB has included an early intervention component in its comprehensive Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) policy in 2012 (Ministry of Women and Children Affairs [MoWCA], 2012). The policy underpins early participation in education for all children irrespective of special needs, ethnicity, and economic status through inclusion. The significant features of this policy are undertaking screening measures for children with disability and providing supports within three years from birth (MoWCA, 2012, p. 16). Since this policy caters inclusive education through early childhood, it is more likely that students as well as their teachers will experience more inclusive culture in regular schools.

WORKING WITH FAMILIES

An effective collaboration between school and home can play a significant role in empowering students with disabilities as well as their parents within the school community (Stanley, 2008). Research suggests that students with disabilities are best served when school and home work together (Sheridan, Bovaird, Glover, Garbacz, & Witte, 2012; Sointu, Savolainen, Lappalainen, & Epstein, 2012). In Bangladesh, school–home relationship (schools working with parents), is one of the less focused areas in education. Accordingly, parents are less likely to appear in the decision making process employed by the schools. Although a number of NGOs are involved in working with families through various programs such as CBR and home-based rehabilitation (USAID, 2005), the state-supported services remained less functional (USAID, 2005). However, in recent years, the GoB seems to underpin community participation in school activities. The third Primary Education Development Program (PEDP-III) is an example where parental involvement has been considered as a means to improving the quality of primary education (DPE, 2013). In its strategy and action plan, PEDP-III has provided a comprehensive guideline on how the existing approaches of parental involvement can be functional. Provisionally, parents of children with disabilities do not have a separate approach to be involved in school activities. Rather they have to take part in the locally developed approaches which are not necessarily considered as ideal approaches. The following section gives a brief of such approaches used to work with families in both government schools and NGOs run schools.

STRATEGIES USED IN GOVERNMENT TO WORK WITH FAMILIES

School Managing Committee (SMC)

SMC is known as a local governing body of the school where a group of parents can directly place their opinion. It is mandatory for every primary and secondary school to have an SMC (DPE, 2009). Generally, an SMC constitutes 12 members including teachers and parents. All the parents of a school elect five members as their representatives in the SMC. Even though the primary aim of SMC is to bridge the gap between parents and teachers, research suggests that due to the lack of awareness about disability, SMC members were found to work against inclusion of students with disabilities (Malak, 2013a; Mullick et al., 2012).

Parent–Teacher Association (PTA)

There is a provision of government that a primary school have a PTA consisting of a group of parents and teachers. Like SMC, PTA is also formed to enhance parental participation in the primary education sector in Bangladesh. However, although a number of steps have been taken to improve governance such as SMC and PTA, the effectiveness of such bodies remains a concern (UNESCO, 2013).

Mothers’ Meeting

Mothers’ meeting (MaaShomaabesh – in Bangla) is a recently developed strategy to encourage parents of children with and without disabilities to be engaged with the school. Since fathers in the context of Bangladeshi families remain busy with income-generating activities, they find little time to participate in programs organized by school. Keeping this in mind, mothers’ meeting has been prioritized with a view that parental involvement would be more effective. Mothers of children with and without disabilities are invited every month to attend a meeting where they are informed about the progress of their children. As there is no published work found on mothers’ meeting, it is difficult to comment on the impact of this strategy.

School Survey

Within the existing provision of the government primary school, teachers need to visit the families of those children who frequently remain absent from classes. The number of teachers in each primary school in Bangladesh ranges from five to seven. Every month, the teachers provide counseling services to such parents by visiting their homes. In a case study of three rural schools in a Northern district of Bangladesh, Islam (2010) reported that frequent home visit had increased the students’ classroom attendance. It is, however, important to note that due to the increased workloads of teachers because of government’s inclusive education policy, they get limited time to do home visit (Islam, 2010).

In addition to the above mentioned strategies, the GoB works with the families of children with disabilities through its Social Welfare Department. In every district, under the Social Service Office, there are several field workers, known as social service workers, who work at grassroots level (NFDD, 2013). The primary responsibility of these field workers is to identify children with disabilities by visiting door to door in subdistrict and provide the families with appropriate guidance and referral services.

STRATEGIES EMPLOYED BY NGOS TO WORK WITH FAMILIES

As mentioned earlier, a number of NGOs work closely with the families of children with disabilities in Bangladesh. For example, Sightsavers Bangladesh has been running CBR programs for children with visual impairments since 2008, and there has been a big change in the empowerment of persons with visual impairment and their families due to the establishment of a strong network (Miles et al., 2012). Also, CBR professionals of BPF conduct door-to-door survey to help identify children with disabilities (USAID, 2005). Community networking is a strategy to serve children with disabilities and their families that has been practiced by several NGOs including NFOWD, Center for Rehabilitation of the Paralyst CRP, CDD, and many other local NGOs. The term “community networking” is conceptualized in the context of Bangladesh as

Networking for us is about communication and making contact, for example with local MPs, the upazila [sub-district] Chairman, rich people, other NGOs, the social welfare department to secure disability allowances, local bank branches, and hospitals to ask for priority service for disabled people. (Miles et al., 2012, p. 288)

Through building network, children and adults with disabilities as well as their parents in rural Bangladesh have increased their participations in the mainstream community. Accordingly, the social inclusion of persons with disabilities has claimed to be improved significantly in rural Bangladesh (Miles et al., 2012). Home- and center-based approaches have also been practiced by numerous national and local NGOs in Bangladesh (Haque, 2008). Most of these NGOs claiming to employ home- and center-based approaches to work with families of children with disabilities are shown as models of good practice of inclusive education in Bangladesh (see CSID, 2007). Lastly, The CDD has developed a model termed as “community approaches to handicap and disability (CADD)” in Bangladesh. The CADD model is originally a systematic approach to implement CBR more effectively in the community. Based on the positive impact of CADD on disability, a number of NGOs have started using this approach in the rural community (USAID, 2005).

TEACHER TRAINING

Over the past decade, the GoB has been keen to focus on teachers’ professional development through preservice and in-service teacher education. As mentioned earlier, a variety of training programs has been conducted with primary and secondary education teachers through PEDP and TQI-SEP programs for preparing teachers to address children with diversity in classrooms. Despite a massive effort for teacher training through different projects, the opportunity of preservice and in-service teachers to develop their teaching skills for accommodating children with disabilities in the government’s mainstream professional development program remains limited (Ahsan, Sharma, & Deppeler, 2011; Ahsan et al., 2012; Khan, 2012). In a review, Malak (2013a) has identified the following institutions as responsible for providing training to preservice and in-service teachers regarding children with disabilities in the context of Bangladesh.

GOVERNMENT’S ARRANGEMENT FOR TEACHER TRAINING

National Center of Special Education (NCSE)

The NCSE is the only government training center that prepares special education teachers. It offers a 10-month Diploma course, known as Bachelor of Special Education (BSEd), for in-service and preservice teachers. A school practicum is mandatory requirement of this program. Students undertake their practice teaching in three different special schools adjacent to the NCSE. The primary focus of the course is on special education with a little emphasis on inclusion of students with disabilities.

Primary Training Institute (PTI)

The GoB provides training to primary education teachers through 56 PTIs. Provisionally every novice teacher needs to complete a foundation training called Certificate in Education (C-in-Ed) from PTI. It is important to clarify that most of the novice teachers in primary education in Bangladesh commence teaching without any prior training. For example, a candidate with a minimum qualification (Year-12 Certificate for female and Bachelor for male) can apply for a teaching position in primary school. Education Degree is not required for applying for this position. Therefore, novice teachers who participate in foundation training in PTIs are treated as preservice teachers.

The critical point is that the entire training program of PTI contains only one chapter focused upon disability. Therefore, although PTIs have potential to prepare novice teachers for inclusive practices, due to the traditional nature of the curriculum, teachers are being deprived of achieving required skills. However, a remarkable change occurred in the training program of PTI which is discussed later under the section of teacher education at University level.

Directorate of Primary Education

The DPE works on behalf of the MoPME for primary education sector. The Inclusive Cell of DPE prepares inclusive education training manuals for Upazila (subdistrict) Education Officers (UEOs). The UEOs then transfer the training to the head teachers and general teachers at the subdistrict level.

Cluster Training Program

Cluster training is one of the innovations of primary education in Bangladesh. Teachers receive a daylong training session once a month in a cluster. A cluster contains 10–12 schools of a subdistrict. Usually education officers at the subdistrict level conduct the cluster training in which teachers are given opportunities to share their experiences and receive feedback on their queries from the education officers. The concept of IE is being integrated in the cluster training program gradually.

Teacher Training College

There are 13 government TTCs in Bangladesh for secondary education teachers. TTCs offer a one-year Diploma in BEd and one-year MEd programs for preservice and in-service teachers. Students of BEd program need to undertake their practice teaching sessions in secondary schools. The TTC curriculum contains a limited unit on disability which seems to be inadequate to prepare secondary education teachers toward teaching students with disabilities.

TEACHER EDUCATION INSTITUTE AT UNIVERSITY LEVEL

Graduate Programs

The IER of the University of Dhaka and Dhaka Teacher Training College under National University provide teacher education programs in both bachelor (four-year) and master’s (one-year) levels. The Department of Special Education of IER prepares 20 teacher education students each year with specialization in disability. To gain hands-on training, BEd (Honors) students are placed in regular and special schools for a period of 6 months. Graduates qualified as preservice teachers from these institutes not only teach at the school level but also contribute to the national level as educational consultants.

Undergraduate Program

There has been a remarkable change in the teacher education program for primary teachers in Bangladesh during the past two years. The C-in-Ed course of PTIs has been entirely revised in an 18-month long program, known as “Diploma in Primary Education” (DPEd). The newly developed program has been pilot tested in seven PTIs and necessary adjustments have been made for commencing. The most important aspect of the DPEd program is that it has been accredited by the IER of the University of Dhaka from 2013. This is the first initiative since the birth of this country when the professional development of the entire primary education sector comes under a University. In a radical departure from the previous teacher training program in Bangladesh, the DPEd is grounded in trainees’ experiences of school placements. The program focuses on the development of both their professional knowledge and ability to create an enabling classroom environment where lessons are taught in an engaging, interactive, and inclusive manner (IER, 2013). The program is modular in structure, with separate subject knowledge and pedagogy courses in six curriculum subjects, four periods of school experiences during which trainees are taught and assessed in accordance with a newly developed set of professional competences. Also, within the program, the professional studies course acts to unify trainees’ practical experience and PTI-based learning with a strong focus on “reflective practice” (IER, 2013). In essence, the DPEd program aims to develop professionally skilled teachers who are able to teach children in a joyful and child friendly environment according to their age and capabilities for their physical, mental, emotional, social, aesthetic, intellectual, and linguistic development, that is, their holistic development (IER, 2013).

Initiatives of Nongovernment Organizations for Teacher Training

The role of NGOs in preparing teachers for inclusive practice seems to be passive (Malak, 2013a). For example, the BRAC is committed to inclusion (Ahuja & Ibrahim, 2006) and currently 28,144 children with disabilities are enrolled at BRAC schools (Mahbub, 2008, p. 34), however, its philosophy, one teacher for one school, sometimes seems to be very challenging to address inclusive practices. Further, the CDD in collaboration with DPE trains primary education teachers for inclusive education and provides training on disability to special education teachers and professionals. While training a huge number of teachers from almost all parts the country, the contemporary research conducted in Bangladesh suggests that teachers’ attitudes are less supportive for accommodating students with disabilities in regular schools (Ahsan et al., 2012). Further, teachers demonstrate lack of knowledge on disability (Kibria, 2005; Malak, 2013b) and inclusive pedagogy (Das & Ochiai, 2012). Moreover, research also suggests that Bangladesh teachers have limited knowledge regarding existing policy, laws, and legislation of education for students with disabilities (Khan, 2012).

PROGRESS OF SPECIAL EDUCATION

Bangladesh has made a remarkable progress in educating children with disabilities during the past decade. Policy reform, teacher training, and awareness creation were consistently reported to have a significant impact on the access of children with disabilities to education in Bangladesh (Ahsan & Burnip, 2007; Ahsan & Mullick, 2013; Ahsan et al., 2012). The following section presents the overall achievement of Bangladesh to promote children with disabilities.

EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES

In policy and legislation context, there has been a significant improvement through which children with disabilities have received their legislative ground for getting enrolled in regular schools (Malak et al., 2014). Education of children with disabilities has been given priority in both primary and secondary education sectors. Due to two major interventions, PEDP and TQI-SEP, there has been significant increase in the enrollment of students with disabilities in regular primary and secondary schools (Ahsan & Mullick, 2013; Das, 2011). Further, the access of students with disabilities to special education has increased. Also, educational participation regarding children with autism has improved noticeably in special education throughout the country (NFDD, 2013). Further, students with disabilities have got access to several basic aspects of education such as extra time in examination and using writers during examination for students with visual impairment and those having cerebral palsy.

TEACHER TRAINING

Training curricula of most of the training institutes have been revised and special and inclusive education issues have been embedded (Ahsan & Mullick, 2013). The issue of disability has been sensitized through CPD with primary and secondary education teachers (Ahsan & Mullick, 2013). In addition, the accreditation of DPEd program by the University of Dhaka will help primary education teachers enhance their teaching efficacy for students with disabilities (IER, 2013).

QUALITY OF LIFE

During the past decade, there has been an increase in disability assessment centers in Bangladesh. While there were only three to five Dhaka-based centers in late 1990s, at present disability assessment centers can be seen in all Divisional cities. Due to the increased awareness of disability in recent years, evidence suggests that misconceptions and superstitions about disability among mass population seem to decrease (NFDD, 2013) and persons with disabilities are more likely to be valued and acknowledged in the society. Furthermore, the use of assistive and educational technologies has improved. Due to improved access to assessment centers, children with disabilities are identified at an early age and are exposed to various technologies based on their needs, such as hearing and visual aids, electric wheelchairs, and white canes which were rare in the past. In order to disseminate services to grassroots level, the government’s plans to set up a special unit on disabilities in every government hospital which will help persons enhance their life.

EMPLOYMENT TRAINING

The Employment and Rehabilitation Center for the Physically Handicapped (ERCPH) has been providing vocational training and rehabilitation of speech and hearing impaired as well as persons with physical impairment since 1978. This is the only government run reputed vocational training center for persons with disabilities. In recent years, the center has increased its capacity in terms of human resource, technology, and physical facilities. At present, it has the capacity to accommodate 85 persons in its residential dormitory (NFDD, 2013). Although employment training for students with disabilities seems to be limited in government sector, a number of NGOs including CRP, CDD, BPF, and Underprivileged Children’s Education Program (UCEP)-Bangladesh have been training these students through different kinds of vocational education (CSID, 2007; USAID, 2005). The students with disabilities are undergoing training in several areas including engineering work, electronics, plastic processing work, leatherwork, wood carving, sewing-machine operator, and bag and brush making (NFDD, 2013; Nuri, Hoque, Akand, & Waldron, 2012).

FUNDING FROM THE GOVERNMENT

The GoB provides financial support to children and adults with disabilities through the Jatiyo Protibondhi Unnayan Foundation (National Foundation for Disabled Development, NFDD) for various purposes including rehabilitation of persons with disabilities, insolvent disability allowance, and a stipend for students with disabilities, and rehabilitation and stipend training for persons with physical impairment. The amount of allowances has increased by 10% during the past five years (NFDD, 2013). Also, the government has established a special arrangement for providing loans to students and adults with disabilities with special offers. Special grants have also been provided through the NFDD to a number of NGOs working in disability since 2002. A total of 380 NGOs have received a total disability grant of Tk. 89,45,000 in the year of 2010–2011 (NFDD, 2013, p. 47).

CHALLENGES TO THE EDUCATION FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

Despite the fact that Bangladesh has gained significant progress in ensuring rights of students with disabilities, it is important to acknowledge that there are numerous challenges that need to be addressed. The first and foremost challenge is that there is no actual data about persons with disabilities in Bangladesh. Without having a national statistics it is hard to plan facilities for children with disabilities. Second, there are some issues embedded in the policies and legislations that lead to confusion among the practitioners and teachers about educational placement of students with disabilities. For instance, while inclusive education has been considered as a means of educating students with disabilities, segregation has been underpinned within the same policies. Therefore, a contradiction exists between special education and inclusive education which creates barriers to facilitate education for students with disabilities. Part of this confusion is the conceptual variation or absence of a common language regarding inclusive education (Ainscow, 2005; Ainscow, Booth, & Dyson, 2006; Ainscow & Miles, 2009) which leads to a major barrier to the successful implementation of inclusion. A third challenge is in teacher training about inclusive education because researchers (e.g., see Ahsan, 2013; Ahsan et al., 2011, 2012) have suggested that although teachers hold positive beliefs, they feel less prepared to teach students with disabilities. This may be due to a lack of experiential learning opportunity for preservice teachers in the teacher training institute in Bangladesh (Malak, 2012, 2013a) because these programs tend to focus more on actual classroom perspective rather than emphasize the theoretical aspect of students with disabilities. Another challenge is curriculum flexibility. The NCTB prepares textbooks for primary and secondary students. It is claimed that majority of textbooks prepared by NCTB remain inaccessible for children with disabilities. On the other hand, there is no national curriculum for students with disabilities who are enrolled in special education. A fifth challenge is the lack of awareness and understanding among various stakeholders including teachers, administrator, SMC, community leaders, and the mass population (Kibria, 2005; Foley, 2009). Another challenge is a lack of collaboration among policy makers, teacher trainers, University academics, NGO professionals, and school teachers in the context of Bangladesh. To remedy this, Ahsan and Mullick (2013) emphasize an interagency collaboration to improve inclusion of children with disabilities in mainstream education. Lastly, the MoE in Bangladesh is dealing with a huge shortage of essential resources such as: teachers, educational materials, accessible classrooms, school buildings, funds for primary and secondary education sectors, and provisions to have a teaching assistant or support teacher. One teacher has to manage nearly 70–90 students in a class.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The national level inclusive and special education policies in Bangladesh are mostly modeled after the international policies. Therefore, it can be hardly expected that the guidelines are underpinned by the inclusion philosophy that fit into the national context. Even within the national context, a noticeable feature of such policies is that they are imposed from the center to periphery (Mullick et al., 2012). This means that teachers and other stakeholders do practice what and how the providers want them to do. Educators have expressed their concerns regarding the increased trend of pursuing top-down and de-contextualized policies where equity is narrowly equated with improved examinations achievements (Ainscow & Goldrick, 2010). Thus, a locally constructed approach of educational placement of children with disabilities is needed in Bangladesh.

REFERENCES

Ahsan, M. T. (2013). National baseline study for developing a model of inclusive primary education in Bangladesh project based on secondary data. Dhaka: Plan Bangladesh.

Ahsan, M. T., & Burnip, L. (2007). Inclusive education in Bangladesh. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 31(1), 61–71.

Ahsan, M. T., & Mullick, J. (2013). The journey towards inclusive education in Bangladesh: Lessons learned. Prospects, 43, 151–164.

Ahsan, M. T., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2011). Beliefs of pre-service teacher education institutional heads about inclusive education in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Education Journal, 10(1), 9–29.

Ahsan, M. T., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2012). Exploring pre-service teachers’ perceived teaching-efficacy, attitudes and concerns about inclusive education in Bangladesh. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 8(2), 1–20.

Ahuja, A., & Ibrahim, M. D. (2006). An assessment of inclusive education in Bangladesh. Dhaka: UNESCO-Dhaka.

Ainscow, M. (2005). Looking to the future: Towards a common sense of purpose. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 29(2), 182–186.

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving schools, developing inclusion. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ainscow, M., & Goldrick, S. (2010). Making sure that every child matters: Enhancing equity within education systems. In and A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, & D. Hopkins (Eds.), Second international handbook of educational change (Vol. 23, pp. 869–882). Netherlands: Springer.

Ainscow, M., & Miles, S. (2009). Developing inclusive education systems: How can we move policies forward? Retrieved from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/COPs/News_documents/2009/0907Beirut/DevelopingInclusive_Education_Systems.pdf. Accessed on February 10, 2013.

Asian Development Bank. (2004). Teaching Quality Improvement in Secondary Education Project: Reports and recommendations of the president. Dhaka: Asian Development Bank.

BANBEIS. (2011). Basic education data and indicators in Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://www.lcgbangladesh.org/Education/reports/Basic%20Education%20Data%20and%20Indicators%20in%20Bangladesh%20-%20CAMPE.pdf

BBS. (2011). Household income expenditure survey. Dhaka: BBS.

CSID. (2007). A study report on documentation of good practices on inclusive education in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Regional Office of South Asia, UNICEF.

Disability Rights Watch Group Bangladesh. (2009). State of the rights of persons with disabilities in Bangladesh, 2009. Dhaka: Disability Rights Watch Group Bangladesh.

Das, A. (2011). Inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream primary education of Bangladesh. Journal of International Development and Cooperation, 17(2), 1–10.

Das, A., & Ochiai, T. (2012). Effectiveness of C-in-Ed course for inclusive education: Viewpoint of in-service primary teachers in Southern Bangladesh. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 2(10), 23–32.

DPE. (2009). School managing committee (SMC). Dhaka: DPE.

DPE. (2010). Training manual for teacher trainers: Inclusive education. Dhaka: DPE.

DPE. (2011). Primary school census 2010. Dhaka: DPE.

DPE. (2012). Bangladesh primary education annual sector performance report (ASPR-2012). Dhaka: DPE.

DPE. (2013). Bangladesh primary education annual sector performance report (ASPR-2013). Dhaka, Bangladesh: DPE.

DPE & CSID. (2002). Educating children in difficult circumstances: Children with disabilities. Dhaka: CSID.

DSHE. (2005). Project proposal of teaching quality improvement in secondary education project. Dhaka, Bangladesh: DSHE.

DSHE. (2007). Teaching quality improvement: What does TQI do? Retrieved from http://tqi-sep.gov.bd/about.php. Accessed on July 15, 2009.

Foley, D. (2009). The contextual and cultural barriers to equity and full inclusive participation for people labeled with disabilities in Bangladesh. Disability Studies Quarterly Winter, 29(1). Retrieved from http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/170/170

Huq, S. (2005). Children with disabilities in different circumstances. Teacher’s World: Journal of Education and Research, 29(1), 78–88.

Haque, S. (2008). Bangladesh CBR. Dhaka: Social assistance and rehabilitation for the physically vulnerable (SARPV). Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/dhaka/education/primary-education/