SPECIAL EDUCATION TODAY IN THAILAND

Kullaya Kosuwan, Yuwadee Viriyangkura and Mark E. Swerdlik

ABSTRACT

The field of special education in Thailand is still in its infancy. This chapter provides a retrospect on special education in Thailand reflecting societal attitudes toward people with disabilities from the past to present. It also provides a list of factors impacting this population and members of the community who are involved with their lives. Special education law, definitions of various disability categories, types of educational settings, as well as issues and challenges in the field are discussed. A critical analysis of special education teacher preparation is also provided. Finally, recommendations and conclusions are offered.

HISTORY OF DISABILITIES IN THAILAND

Although people with disabilities have lived in Thailand as long as in other countries, their treatment in the past has been a mystery because no historical records were found regarding lives of and services provided for this population. Searching the literature for “history of disabilities in Thailand” only yielded the history of the field of disabilities and special education in the United States and Europe. An explanation for why there is no record of these people as if they did not exist can be attributed to several reasons.

First, a large majority of people in Thailand (94.6%) are Buddhists (National Statistical Office of Thailand [NSO], 2013a), which has a tremendous influence on the lives of people with disabilities and societal attitudes toward various types of disabilities and the people who possess them. Buddhists believe in Karma which refers to the cause and effect cycle that actions in the past are passed on to what is happening today. Disabilities are believed to be a result of sins that parents or persons with disabilities themselves committed in previous lives or as part of their own past. Although this attitude is less prevalent today, a majority of Thai people still believe that parents of individuals with disabilities or those individuals themselves are “paying back” to whomever they owed. Because parents were ashamed of “their sins,” it was unlikely that disabilities were openly discussed or accurate records kept (Thammarak, 2013).

Second, individuals with disabilities were likely perceived as “not able” and, therefore, unimportant. Being asked whether they recalled having contact with or even observing people with disabilities when they were young, the elderly in Thailand (i.e., in their 80s) said individuals with disabilities wandered around their communities but admitted that their memories were blurred because they did not pay much attention to those people with disabilities. They knew that people with disabilities were fed and assisted by their families with all daily life activities, but those individuals never had an opportunity to participate in family or community events (e.g., weddings or religious celebrations) due to difficulty “controlling” themselves and the shame felt by their parents. There were instances when people with disabilities were seen at special events (e.g., temple fairs) alone where many would beg for money, but they never attended schools prior to the 1940s. In some cases, adults with intellectual disabilities were locked or chained at home to prevent self-injury or harm to others or were treated in psychiatric hospitals as they were viewed as having mental illnesses (Dheandhanoo, 1992).

Third, Thai society has never valued data in making decisions. Historical records are difficult to locate not only related to people with disabilities, but also in the field of special education. It is, therefore, not surprising that the lives of people with disabilities were not recorded (Onkoaksoong, 1984; Punlee, Wongwan, Nildam, & Intapanya, 1973).

Early Efforts Prior to Special Education Legislation

The oldest evidence of individuals with disabilities appearing in an official record was the Compulsory Education Acts (1935). The acts “allowed” children and youth with physical and mental disabilities as well as children who lived in poverty to opt out from normal compulsory education. This supported the anecdotes of the Thai elderly and explained why students with disabilities were never observed at school. This “exemption” continued until 1980. Although, at the first glance, it seemed convenient for parents, children with disabilities, and children who lived in poverty; government officials later realized that this opt-out did not benefit those children, their parents, nor the country as a whole in the long run (Srinakharinwirot University, 2013). This led to an awareness of the need for education for people with disabilities resulted from contributions from several individuals in the late 1930s. One of them was Genevieve Caulfield.

Genevieve Caulfield who was an American English teacher with a visual impairment visited Thailand and learned that children who were blind received neither financial support nor an education. She went back to the United States and raised money for her mission in Thailand. Returning to Thailand in 1938, Caulfield worked with a small group of Thai educators to develop Thai Braille characters. It was noted that “this was contemplated to be a great success as Thai language has 44 alphabets, 32 vowels, and 4 tonal marks which as much more than 26 English alphabets” (School for the Blind, 2013, para. 4). Caulfield rented a small house in Bangkok to set up a classroom for children with low vision and blindness. The classroom developed into the Foundation for the Blind in Thailand (FBTQ, 2013) in the following year (1939) with support from donors. Resigning after World War II, Caulfield asked sisters and Salesian priests to continue her work. She also founded schools for the blind in Chiangmai (in the North of Thailand) and Vietnam in 1956. The Foundation for the Blind in Thailand (currently known as the Foundation for the Blind in Thailand under the Royal Patronage of H.M. the Queen) founded the School for the Blind, contributing to students with visual impairments appearing more in the public. Later, this project was expanded into more schools for the blind in the North (Chiangmai), the Northeast (Khonkaen), and the South (Suratthani; FBTQ, 2013).

The Ministry of Education (MOE) recognized the need for special education and started a demonstration project in 1951 to educate slow learners who could not keep up with their classmates academically, students with sensory impairments, physical disabilities, and chronic illness (Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University, 2011). This movement has never been linked to Caulfield’s work, but it is reasonable to assume that it was influenced by the Foundation for the Blind. Other significant changes also took place in the 1950s. In 1954, a self-contained classroom for students with hearing loss developed into the first School for the Deaf in Thailand (Setsatian, 2013). In 1956, with the support from the Foundation for the Blind in Thailand, high school students with blindness were included in general classrooms at St. Gabriel’s School, a well-known private school in Bangkok (Srinakharinwirot University, 2013). One year later, the MOE initiated a pilot project to integrate students who were considered slow learners into seven Bangkok Metropolitan public schools.

The Foundation for the Welfare of the Crippled was established in 1954 and, two years later, received support from the Royal Patronage of H.R.H. the Princess Mother. The foundation provided educational services at Siriraj Hospital for children with physical disabilities and chronic illness caused by polio or meningitis and were originally taught by physician and nurse volunteers. Later, in 1958, the Special Education Division under the Department of General Education, MOE, sent itinerant teachers to provide an educational program for in-patient children where there were 17–25 students from preschool to college level (Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University, 2011). In 1961, the School for Children with Physical Disabilities was established, and later it was named after H.R.H. the Princess Mother, Srisangwan School (Srisangwan School, 2013; Table 1).

Table 1. Years of Important Events.

| Year |

Important event |

| 1939 |

Foundation for the Blind in Thailand was established. |

| 1951 |

The MOE set up the first special education classroom for slow learners and students with sensory impairments, physical disabilities, and chronic illnesses. |

| 1954 |

School for the Deaf (Setsatian School) was founded. |

| 1956 |

St. Gabriel’s School allowed students with visual impairments to participate in general education classrooms, and those became the first inclusive classrooms in Thailand. |

| 1959 |

The first disability survey in Thailand was conducted by World Health Organization. |

| 1960 |

The Hospital for the Mentally Retarded (Rajanukul Institute) was founded. |

| 1961 |

School for Children with Physical Disabilities (Srisangwan School) was established. |

| 1980 |

Division of Special Education was the first government unit directly responsible for special education in Thailand. |

Related to intellectual disability, services emerged because of domestic and international influences. In the 1950s, Professor Phon Sangsingkaew, a physician and Director of Somdet Chaopraya Hospital (a psychiatric hospital), suggested that people with intellectual disabilities were not mentally ill and should be treated accordingly. He went on to support Dr. Roschong Dhasananchalee, a psychiatrist, for a training course in the area of intellectual disabilities in the United Kingdom in 1953. In 1959, the research team of the World Health Organization (WHO), collaborated with the Ministry of Public Health, surveyed incidence of intellectual disability in Thailand, and reported that 1% of Thai population had intellectual disabilities of various levels of severity (Komkris, 1989; Kosuwan, 2010). Based on this finding, the Thai government became aware of people with intellectual disabilities and attempted to provide more services for this population.

Upon his return, in 1960, Dr. Dhasananchalee established the Hospital for the Mentally Retarded and became its first director. The hospital has since provided diagnostic, treatment, and rehabilitation services for these individuals. In addition to the medical services, the hospital has also provided special education services for school-aged children with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities in the Rajanukul Special School. Renamed as Rajanukul Institute in 2001, the hospital has remained to this day the first and most well-known hospital for multidisciplinary services for individuals with intellectual disabilities (Komkris, 1989; Rajanukul, 2013).

Another important organization involved in the area of intellectual disability in Thailand is the Foundation for the Welfare of the Mentally Retarded of Thailand under the Royal Patronage of Her Majesty the Queen established in 1962 by a group of interested citizens led by Prince Prem Purachatra’s wife (Mom1 Ngarmchit Purachatra). This foundation has provided services for individuals with intellectual disabilities through community-based early childhood centers, schools, and vocational training centers in Bangkok, the North, the Northeast, and the South of Thailand (FMRTH, 2013).

The field of disability studies became established in 1980, and the MOE assigned the Division of Special Education, under the Primary Education Department, to administer the provision of education to children with disabilities and children from disadvantaged backgrounds. In 1998, the Division of Special Education was divided into the Division of Education for Individuals with Disabilities (DEID) and the Division of Education for Individuals from Disadvantaged Background (BSE, 2011). Despite the DEID being directly responsible for people with disabilities, no legislation existed to mandate appropriate education for this population.

Finally in 2003, there was a structural reform of the MOE by combining three departments including the Office of National Primary Education Commission, Department of Primary Education, and Department of Curriculum and Instruction Development into the Office of the Basic Education Commission (OBEC). The MOE also combined the DEID and the Division of Education for Individuals from Disadvantaged Background into the Bureau of Special Education (BSE, 2011).

The Royal Family and the Field of Disabilities

In addition to services provided by the government, the royal family has also played a key role in the field of disabilities in Thailand. For instance, with support from H.R.H. the Princess Mother Srinagarindra, Siriraj Hospital launched a rehabilitation project to provide services for children with physical disabilities from disadvantaged backgrounds (Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University, 2011). Her Majesty Queen Sirikit has also supported several foundations such as the Foundation for the Blind in Thailand under the Royal Patronage of H.M. the Queen (FBTQ, 2013) and the Foundation for the Welfare of the Mentally Retarded of Thailand under the Royal Patronage of H.M. the Queen (FMRTH, 2013). The School for the Deaf has been supported by His Royal Highness Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn since 2002 and is currently known as Setsatian School for the Deaf under the Royal Patronage of His Royal Highness Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn (Setsatian, 2013).

The involvement of the royal family with the field of disabilities was even more prominent when Khun Poom Jensen moved to Thailand with his mother, Her Royal Highness Princess Ubolratana Rajakanya, in 2001. Raised in the United States and having lived a few years in Thailand, Khun Poom, diagnosed with autism, could fully participate in daily living activities valued by the population without disabilities. Autism has received attention from all parties across the nation, and Khun Poom’s story brought great hope to Thai parents that children with autism could learn and contribute to society. Sadly, he was one of the victims of tsunami in Khao Lak, Phang Nga province in 2004. In 2005 after his death, Princess Ubolratana established the Khun Poom Foundation to provide financial support for educational purposes to low SES children who have autism or intellectual disabilities (Khun Poom Foundation, 2013). Generous support from the royal family has been, and continues to be, one of the most significant pillars of support of the field of disabilities in Thailand.

Individuals with Disabilities and Laws

Although there have been a number of constitutional laws since 1932, the rights of Thai citizens with disabilities such as equal access to public services was not part of constitutional law until an amendment in 1997 (NEP, 2013a). According to that constitutional law (1997), individuals with disabilities have rights to access and benefit from social welfare, public utilities, as well as other appropriate support from the government in order to be as independent as possible and attain the highest quality of life.

In fact, medical and vocational supports and services as well as accommodations related to government procedures and legal services in case of a lawsuit were mandated in the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons Act, B.E. 2534 (1991) before the constitutional law (1997). The act mandated that Thai citizens who were registered as individuals with disabilities must receive an appropriate education, given access to participate in community activities, as well as securing necessary assistive technology and other services appropriate for people with disabilities (Roonjareon, 2013). Although mandated by law, a number of children with disabilities in some geographical areas of Thailand were denied access to public education in the 1990s because the emphasis of this act was access to community activities and providing financial support, not education (Chandrakasem Rajabhat University, 2013).

The Era of Mandated Special Education

After the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons Act, B.E. 2534 (1991), education for people with disabilities was legislated again in the National Education Act, B.E. 2542 (1999; MOE, 2013). Even though the National Education Act, B.E. 2542 (1999) was not an official special education law, it was one of the most prominent education laws that led to special education in Thailand for several reasons. The act caused the MOE to announce the year 1999 as “The Year of Education for People with Disabilities,” and that launch had a profound impact on the field of special education. The slogan “Every person with a disability must have access to education” gave a signal to all educational institutions that the “Zero-Reject” policy must be in place (but this was not fully implemented in reality). Although this policy did not include a mandate for all schools to implement, it was an initial move to provide education for children with disabilities in general education schools. There were gradual increases in the number of schools that offered to include children with disabilities particularly in self-contained classrooms. The MOE also heavily advocated that institutions of higher education increase the number and quality of special educators. In that particular year, the Ministry of Finance provided an extra allowance for special educators who met specific criteria. Most importantly, the act led to Thailand’s first official special education law in 2008 (Chulalongkorn University, 2012). The National Education Act, B.E. 2542 (1999) yielded significant benefits to the field of special education.

Special education appeared, for the first time, in Thailand’s constitutional law in 2007. The new constitutional law mandates that, “Every Thai citizen must have equal access to free, quality education for at least 12 years in one’s life. The government must provide assistance to those who live in poverty, come from disadvantage backgrounds, or have disabilities to have equal access to education” (NEP, 2013b, p. 13). This constitutional law was another law that led to Thailand’s first official special education law, the Persons with Disabilities Education Act, B.E. 2551 (BSE, 2012). The Thai special education law was also influenced by American special education law (i.e., the Individuals with Disabilities Education and Improvement Act or IDEA, 2004) and the United Nations General Assembly's Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 (Chulalongkorn University, 2012)

The Persons with Disabilities Education Act, B.E. 2551 (2008) mandated that individuals with disabilities must have rights to receive free education, assistive technology, and other educational support from birth or since one’s diagnosis throughout their lives. Each individual has rights to select services, settings, systems, and types of education according to one’s abilities, interests, skills, and special needs. Also, education provided must reach national standards, have quality assurance, and match individuals’ special needs. Special educators, educational institutions that serve students with special needs, and research projects focusing on improving special education will receive financial support. Individualized Education Plans, appropriate types of instruction, environment, and other educational support are required. Schools must not deny students with disabilities (NEP, 2013c).

DISABILITY CATEGORIES

To provide an appropriate education to students with disabilities, the BSE organized disabilities into nine categories and defined each disability category as follows (MUA, 2013).

- Visual Impairment includes low vision (a vision between 20/70 and 20/200 after correction) and blindness (a vision of 20/200 or more after correction and those who cannot sense light).

- Hearing Impairment includes hard of hearing (hearing loss between 26 and 90 decibels) and deaf (hearing loss at 90 decibels and above).

- Intellectual Disability is defined as having below average intellectual functioning and deficits in two out of 10 adaptive skills before age of 18. The 10 adaptive skills include communication, self-care, home living, social skills, community use, self-direction, functional academics, work, leisure, and health and safety.

- Physical, Mobility, or Health Impairment is defined as (a) losing or having problems with parts of body, bones, muscles that cause difficulties in movement, or (b) having a chronic illness that requires long-term health care and becomes an obstacle to education.

- Learning Disabilities includes brain dysfunctions that cause difficulties in learning one or more academic skills (e.g., reading, writing, mathematics) despite normal IQ.

- Speech and Language Disorders includes problems in producing sounds (e.g., distortion, abnormal speed or rhythm) and/or problems in expressive or receptive language (i.e., oral, written, or other forms).

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders is defined as markedly and continuously deviant behaviors caused by mental illness or brain dysfunctions (e.g., schizophrenia, depression, dementia).

- Autism is caused by brain dysfunction and results in multiple impairments in language and social development, social interaction, and restricted behaviors or interests. The age of onset is before 30 months.

- Multiple Disabilities is defined as having more than one disability.

Despite these definitions, some teachers and administrators still cannot use these categories in their real-life practice due to lack of knowledge of disabilities and special education.

TYPES OF EDUCATIONAL SETTINGS

Several governmental units are responsible for the education of individuals with disabilities between 3 and 18 years of age. The OBEC has provided inclusive education in selected public schools throughout Thailand. The BSE’s responsibility covers 43 special education schools, 63 provincial and 13 regional special education centers, and 25 social welfare schools. The Department of Non-Formal Education (NFE) also provides education to individuals with disabilities who cannot attend schools (BSE, 2012). Additionally, there are students with disabilities in inclusive private schools, schools under the control of the Ministry of Interior, and educational institutions under the control of the Ministry of Public Health. Details are provided below.

Inclusive Public Schools

In 2011, 242,888 students in the nine disability categories were educated in 18,370 inclusive public schools nationwide. Educational services in those schools, however, vary depending on school administrators’ policy. The term “inclusive school” is unclear whether it provides full-time inclusion (i.e., students were instructed the full day in general education classrooms), part-time inclusion (i.e., students with disabilities spend most of their day in general classrooms but were pulled out for a few hours for small group or individualized instruction in a resource room), or full-time segregation (i.e., students were instructed in separate self-contained classrooms in general education schools). In addition, no definitive guidelines exist as to who should receive education in which type of setting. In most cases, final decisions are made solely by school administrators and are dependent on the inclusive options a particular school can offer. In some cases, the personal relationships between special education teachers and general education teachers also play a part in students’ placement.

Although most parents desired their children with disabilities to be included in classrooms of same-aged peers regardless of their degree of participation in typical community activities, it is unlikely for those children with more significant disabilities to be included in general education classrooms. This is due to a number of factors. First, general education teachers have limited knowledge and skills in dealing with children with special needs. Second, those teachers are unable to provide accommodations and modify instructional content and curricula taught in general education classrooms. Third, typical classrooms are large (i.e., approximately 35–45 students taught by a teacher) and so, even though general educators may want to comply with the special education law, they are reluctant to have students who need extensive support in their classrooms.

From the authors’ experience, most inclusive schools have only one or two special education teachers instructing in self-contained classrooms or resource rooms, and some of these special education teachers were hired by the regional or provincial special education centers, not the schools. For some schools that enroll only a few students with diagnosed disabilities, it would be more likely that the school would not employ a special education teacher. If this is the case, the students with disabilities remain in general education classrooms with their same-aged peers, but this may represent only “physical inclusion” and may not represent an appropriate education for those students.

Although the authors have had opportunities to observe general education teachers who adapted and modified the curricula and lessons, teaching strategies (e.g., hands-on activities instead of lectures or implemented peer tutoring), and evaluation processes (e.g., more time for tests or reading test questions to a student), adaptations and modifications for students with special needs in general classrooms are uncommon in Thailand. Moreover, most general education teachers are unfamiliar with assistive technology (e.g., FM device to amplify sounds for students with hearing impairments or Braille for students with visual impairments) because assistive technology is considered the responsibility of the special educator and the student. These examples provide an illustration of how general education teachers would struggle when they have students with disabilities enrolled in their classrooms without the support of a trained special educator.

Although the MOE has provided numerous special education training courses to enable general education teachers to work effectively with students with disabilities in general education classrooms, this approach has not been as effective as anticipated. Recently, scholars in the field of special education have articulated advantages of inclusive over segregated education, but a majority of people in the Thai society still believe that a stand-alone special education school is the best option for individuals with disabilities because of lack of school personnel’s expertise in working with this population (Rattanasakorn, 2007).

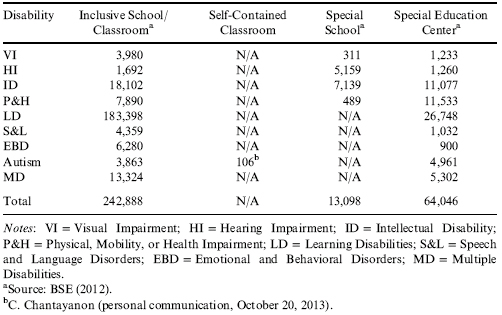

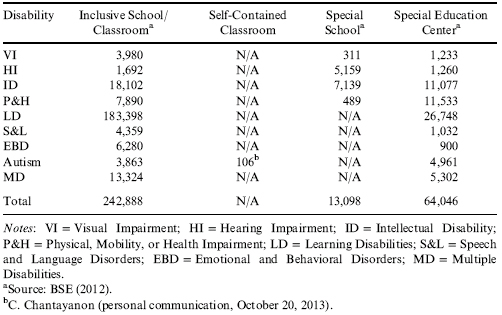

Special Education Schools

Thailand has established 43 special education schools in 35 provinces including 20 Schools for the Deaf, 19 schools for students with intellectual disabilities, two Schools for the Blind, and two schools for students with physical and/or health impairments (Wipattanaporn, 2014). The numbers of students in each disability category classified by type of school are presented in Table 2. These special education schools serve students in Grades K-12. Since most of these special schools were located far from the centers of towns, it is likely that transportation represents a major obstacle for students with disabilities and their families coming from homes to schools. Therefore, all special education schools are residential to address the problem of the lack of public transportation (Viriyangkura, 2010), although most of them also educate local day students.

Table 2. Number of Students with Disabilities Classified by Type of Educational Setting in 2011.

As their names imply, each school was established to serve students with a specific disability. In reality, however, these special education schools also enroll students with other disabilities. For example, in 2003, Lopburipanyanukul School (a special school for persons with intellectual disability in Lopburi province) had 148 students with intellectual disabilities, 154 students with hearing impairments, 9 students with physical disabilities, and 7 students with autism. The following year (2004), the school served 166 students with intellectual disabilities, 121 students with hearing impairments, 10 students with physical disabilities, 13 students with autism, and 7 students with specific learning disabilities. Currently, this special school has 266 students with intellectual disabilities, 41 students with autism, and 5 students with physical disabilities (Lopburipanyanukul, 2013).

Curricula used in schools for persons with intellectual disabilities have recently been changed from eight subject areas taught in general education schools to a functional curriculum to suit these students’ needs. Schools for the blind and for the deaf, however, try to prepare their students who are at an age-appropriate level functioning for being educated in general education schools. Despite the difference of the curricula, self-help skills (e.g., dressing, grooming, health care, household chores) are the foci of the curricula. Instructional strategies employed in this type of school typically focus on task analysis, shaping, chaining, reinforcement, and typical teaching methods. At present, most special schools have made efforts to develop programs to prepare adolescents for their careers and their transition to adult lives, but these efforts have not been as successful.

Special Education Centers

Special education centers were established in every province for several purposes. The primary purposes of each center are to provide early intervention services to young children with disabilities, to prepare young children with disabilities for both general education and special education schools depending on their level of abilities, and to educate individuals with disabilities in hospitals or at home (Wipattanaporn, 2014). Responsibilities of these special education centers are also to support teachers in general education schools to provide an appropriate education to children with disabilities (e.g., establish inclusive classrooms or resource rooms and teach educators how to write an individualized education program) as well as to support parents of children with special needs. The special education center network includes 13 regional special education centers and 63 provincial special education centers (BSE, 2012).

In handling a variety of functions, special education centers use different strategies dependent on the age, type, and degree of severity of disability, as well as needs of individual children and families. Because professionals employed by special education centers work with various organizations, effective communication and a high degree of cooperation represent key factors in their success. Although special education centers have similar goals and objectives, the effectiveness of their services are heavily based on their director’s policy and leadership skills.

Non-Formal Education

The Department of NFE was developed to serve individuals who wanted to receive education but could not participate in formal classes for several reasons. Provided in homes or hospitals, NFE services include programs in Grades 1–12 and vocational programs taught by NFE teachers from the MOE, teachers from private organizations, and volunteer teachers from nonprofit organizations (Dhammaviteekul, 2009; Wipattanaporn, 2014). The BSE (2012) reported that 3,559 individuals with disabilities were educated in Grades 1–12; 3,223 in vocational programs; 2,051 in Sustainable Community programs; and 3,266 in recreational and other services programs.

Educational Institutions Outside the MOE

In addition to the schools and the special education centers administered by the MOE, there are a number of institutions that provide educational services to children and youth with disabilities. Schools under the administrative control of the city of Bangkok are an example of public schools under the Ministry of Interior. A few special education schools are attached to hospitals (e.g., Rajanukul School for children with intellectual disabilities), and so are under the administrative control of the Ministry of Public Health. There are 16 private special education schools and 644 private inclusive schools in Thailand. Moreover, six special education centers were founded and managed by departments of special education in Rajabhat Universities (BSE, 2012; Wipattanaporn, 2014). These educational institutions have different policies and practices when working with children with special needs.

CONCERNS AND CHALLENGES IN SPECIAL EDUCATION

The field of special education in Thailand is still in its beginning stages, so comparing special education in Thailand to well-established systems in Western countries would inevitably lead to a lengthy list of concerns and challenges. Due to limited space, however, we present only selected issues that require serious attention from everyone associated with the field of special education.

Lack or Excess of Data

Thailand has never been a data-driven society. Searching for data in any field of study, in hard copy or digital format, is a challenge. Some useful data were never retained, some data were relocated without prior notification or a link provided, and some data were removed from their sources for no apparent reason. For instance, the MOE deleted a document Special Education Strategic Plans 2012–2017 (BSE, 2012) from its website at the end of 2012. A report on the performance of special education teachers (Chulalongkorn University, 2012) was removed from The Teachers Council of Thailand website in July 2013. Moreover, decisions related to keeping data have been arbitrary.

Some educational statistics reported in the field do not align. For example, the OBEC (2013a) reported that 66,330 students with disabilities were included in Grades K-12 in 2012, but the MOE (2013) reported 237,779 students in inclusive schools in 2012 and the BSE (2012) reported 242,888 students in inclusive schools in 2011. Lack of consistency in data collection can be attributed to several possible reasons. One explanation is the fact that special education is new and considered unimportant. Key responsible organizations (e.g., NSO), therefore, did not keep records related to the population with disabilities as compared to the general population. Additionally, organizations collecting data have worked independently which represents another explanation. When collaboration between agencies did not exist, data reflected only small parts of the picture rather than the whole.

On the other hand, there were a number of educational organizations that provided all of the statistics and personal information (e.g., name, age, disability, ID card number, school name, parents’ names, home address, and telephone number) for students with disabilities in a particular school or district for public access. A fine line exists between “too little” and “too much” data for public consumption, and this represents another issue that should receive attention in the field.

Individuals with Disabilities Not Enrolled in School

In 2005, the literacy rate in Thai population was 93% (MOE, 2005). Despite the plan to increase the rate to 95% in 2012 (Thairath, July 3, 2009), Thailand’s literacy rate has not increased. The general population rate was significantly higher than the rate for those with disabilities. The NSO reported that among 1.5 million people with disabilities at ages 5 years and above, 22.40% never attended school, and 57.60% did not complete sixth grade level. Whereas those in the general population did not attend schools because they did not have financial support (37%) or they were responsible for earning a major portion of income for their families (39%), 65% of people with disabilities did not attend school because their disabilities were “too severe” to receive education (NSO, 2013b, 2013c).

Several reasons for the lack of attendance of those with disabilities include that their parents did not value education for their children, or they may live a distance from school prohibiting attendance. A number of parents, however, reported that they wanted their children to attend school, but school administrators or administrative teachers refused to accept these children because the schools lacked qualified personnel to teach them. Those schools also suggested parents have their children attend another school that “could educate them” (Manager Online, July 6, 2013; Rattanasakorn, 2007). Although this denial of services was illegal, one must consider several factors such as a lack of special education teachers available in such schools. In addition, special education teachers are employed in only leading inclusive schools designated by the OBEC. Further, despite various special education training programs for general education teachers, trainees were too small in number and, without administrators and colleagues’ support, these trainees could not implement what they learned. It is, therefore, not unexpected that many schools in Thailand would be uncomfortable accepting students with special needs. The question remains, however, how do schools continue to deny school-aged children with special needs services mandated by law without penalty from the MOE.

After a number of petitions on behalf of parents of children with disabilities were filed, the BSE Director announced in the media that the Persons with Disabilities Education Act, B.E. 2551 (2008) would prevent the “schools’ denial” (Daily News, December 17, 2007). As mentioned earlier, children and youth with disabilities are still rejected by public schools (TJIC, 2013). The MOE also attempted to increase the quality and quantity of special education teachers by issuing policies regarding special education programs. These policies were aimed to support (and push) higher education institutions throughout the country to increase program quality and raise the capacity to increase the number of special education personnel produced. The results, however, as discussed in the next section, were unsuccessful.

Lack of High Quality Individualized Education Programs

A large majority of, if not every, special educators in Thailand learned that students with disabilities require individualized education programs (IEPs). Writing IEPs is a skill taught in all preservice programs and as part of continuing professional development offered by the OBEC and the BSE. Further, special educators receive an extra allowance after they have submitted IEPs to the BSE to reflect the number of students with disabilities they are serving each semester. Despite these possible explanations, a number of educators teach their students with disabilities without an IEP. Moreover, a number of teachers have low expectations related to the abilities of their students with disabilities, and therefore the content and methods used are often inappropriate for the students’ ages and ability levels. Some students had IEPs, but the documents did not serve the purposes for which they were designed (e.g., teachers did not seek agreement from parents for services, IEPs were written by individual teachers rather than the team, and IEPs of students in the same class were almost identical).

There are several possible reasons for IEPs not being developed for individuals with disabilities. First, some teachers admitted they did not know how to write IEPs and to provide services consistent with the IEP (Chulalongkorn University, 2012). Second, IEPs in many schools are developed by individual general or special educators, not IEP teams. Therefore, the documents are developed based on one person’s knowledge. Third, school administrators often do not check or verify the IEPs. Fourth, the BSE does not have an appropriate evaluation system in place. Finally and perhaps most importantly, parents of students with disabilities do not understand the meaning of an IEP and did not see the value of this document. Parents, therefore, approve “whatever” teachers prepare for them. Although the OBEC and the BSE have provided training to special educators throughout the country, education authorities would not know whether IEPs submitted by teachers accurately reflected each student unless parents were actively engaged in the IEP process.

Lack of Preparation for the Post-School Life

Transitions represent a particularly critical juncture in the lives of high school students with disabilities because they are moving from childhood to adulthood with decreasing support along with higher societal expectations for independence. The transition planning process including developing individualized transition plans, however, is not common practice regardless of educational level (e.g., preschool to elementary school and high school to postsecondary education or employment). As a result, most students with disabilities and their families must redo the educational planning process each time there is a move to a new school, to the next phase of life, or even to the next grade with a new teacher.

Special education schools represent an educational setting that utilizes Individualized Transition Plans (ITPs) for students with disabilities for educational planning. However, ITPs typically do not take into account the needs of the individuals with disabilities and their families. Instead, the ITP development process includes having the student’s teachers choose from a “menu of careers” for their students. Many of these careers are unrealistic for individuals with disabilities. For example, a special school provides training for a student with disability in agriculture when in fact his family does not own a piece of land. In Thailand, a large number of students with disabilities graduate with no idea of what to do next. Many remain at home after graduation and this situation is exacerbated in inclusive schools because their students are assumed, just like their peers, to continue postsecondary education. As a result, ITPs are not being developed for these students.

It is not surprising that, in 2012, 74.3% of individuals over the age of 15 with disabilities were unemployed (NSO, 2013d). Out of that group, individuals ages 25–59 and youth ages 15–24 years old represented a substantial portion (19.90 and 4.5% accordingly) that were unemployed. Furthermore, the NSO reported that among the 25% of the employed group, 18% worked in agriculture, fishery, and other low-paid jobs. In addition, no records exist reporting which disability groups are employed and which are not. It is possible that the most employed individuals are those with learning disabilities and mild physical disabilities, whereas a majority of people with intellectual disability, sensory impairments, and multiple disabilities remain unemployed, but we do not know.

Problem of Accurate Monitoring Systems

Special educators working in general education schools are formally supervised and monitored by school level administrators and educational supervisors (special education) located in each geographical area of Thailand. There is, however, a lack of supervisors providing support and consultation for general education teachers who give instruction to children with special needs in inclusive classrooms. To solve this issue, educational supervisors in other areas received brief training courses in special education to provide special education supervision to those general education teachers. With a lack of a rigorous monitoring system and an absence in special education knowledge and skills of some educational supervisors, the centralized MOE would be unaware of any problems and teachers were not supported.

Although Thai parents view teachers as authority figures and are “good followers,” there are instances that small groups of local families have submitted petitions to the MOE claiming that the education of their children with disabilities was not at no cost to them. Also, they complained that their children were denied admission by schools, or schools “falsely used” their children’s names to secure special education financial support. Unfortunately, the impact of this parent advocacy has not been strong enough to lead to changes in these special education practices that are occurring nationwide (Thairath, January 18, 2013).

Historically, there were situations in which parents monitored the teaching by themselves based on their child’s development. It is also the case, however, that many parents fear the consequences of providing negative reports of their child’s teachers. These consequences can range from their child being ignored to being mistreated.

Lack of Strong Parent Movement and Advocacy

Even though a teaching career is not as attractive to a new generation of Thai young adults as it was in the past (Manager Online, April 26, 2013), teachers generally remain well respected as experts and authoritative figures by parents. There are occasionally some parents of children with disabilities who possess effective communication skills and could advocate effectively for their children, but most Thai parents would never “go against” the teachers’ opinions.

Chulalongkorn University (2012) conducted a study of the field of special education and reported that parents and guardians were dissatisfied with the special education services and educational supports (e.g., assistive technology) their children were receiving. Additionally, participating parents and guardians reported that special educators did not possess adequate knowledge and skills. This view was consistent with the self-perceptions of participating special educators who noted, for example, that they did not possess the skills to provide an inclusive education, develop an IEP, and/or address the behavioral problems of their students.

More recently, there are several parent groups and disability associations in Thailand. Although all of these groups are slowly moving the field forward, similarly to other developed countries, the most powerful group represents parents of children with autism. The Association of Parents of Thai Persons with Autism (AU Thai) has developed a network of parents in 76 provinces nationwide and demanded the MOE provide “parallel classrooms” which refer to self-contained classrooms for students with moderate and severe autism located in the same school of their typically developing peers (C. Chantayanon, personal communication, October 20, 2013). According to the AU-Thai’s document, however, the future of these classrooms is uncertain as the funding for teachers’ salaries is dependent on the governmental budget which varies on a year-to-year basis. This parent advocacy group also strongly influenced policy makers and special education legislation in Thailand.

Parents of children with disabilities are also employing social networks (e.g., Facebook) to communicate and share information among themselves and as a means to provide support to members. A limitation of this communication medium, however, is that only parents from middle- to high-class families have access to information technology, while many parents who reside in rural areas do not have access to the Internet and depend on their local government (e.g., Subdistrict Administrative Organization), school administrators and teachers, and informal communication with neighbors to provide them with information and support.

SPECIAL EDUCATION TEACHER PREPARATION

Over 40 years ago, the MOE contracted with Suan Dusit Teachers’ College to create a demonstration program to educate young children with hearing impairments, and the program developed into the first bachelor’s degree program in special education in 1970 (Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University, 2011). Prior to 2004, a bachelor’s level preparation program in special education and other specialty areas required three and a half years of course work and one semester of field experience. Critics of the quality of teachers including special educators, however, caused the MOE to extend the field experience from a semester to a year resulting in an increase in the time to degree completion from four to five years (MUA, 2011). Compared to 4-year bachelor programs in other fields and 6-year bachelor programs in medical specialties, however, these 5-year bachelor programs in special education did not attract the same high quality (e.g., having high GPAs) high school students.

Recently, the MOE announced a double-major program policy that requires special education preparation programs to pair with another education major (e.g., language arts, mathematics, or science) with the expectation that these teachers will be able to provide instruction for typically developing students as well as those with special needs in general education settings. A group of teacher educators argued that the longer field experience and the “hybrid special education” program would solve only a part of the quality problem. It is because most courses in these preparation programs still focus more on general disability information and theories of instructional strategies but less on the relevant hands-on and field experiences. Therefore, instead of addressing critical issues in the field by increasing the quality and quantity of pedagogy courses and field experiences provided for future special educators, the MOE is adding more pressure on teacher preparation programs through these recent policies.

Teacher Shortage

Currently, Thailand has 14 higher education institutions including large universities in major cities and Rajabhat Universities (previously known as community teachers’ colleges) that offer bachelor’s (nine institutions), master’s (six institutions), and doctoral (two institutions) special education preparation programs (MUA, 2013). Each program, however, is limited in the number of future special educators it can prepare each year (approximately 20–50 undergraduate students and 10–20 master’s level students annually; Arrayawinyoo, 2001; MUA, 2013). Based on these enrollment limitations, the shortage of special educators remains a critical issue in the field (Chulalongkorn University, 2012).

Based on the statistics presented in Table 2, Thailand has over 300,000 students with disabilities educated in various settings. This 300,000 does not include nearly 200,000 other individuals with disabilities who have never received formal schooling (NSO, 2013c). Although the OBEC (2013b) reported that 2,154 special education teachers were qualified for extra allowance from the MOE in 2012 (Manager Online, December 4, 2012), the number of teachers working in each type of educational setting such as a special education school or an inclusive school was unknown. Assuming an appropriate ratio of teachers to students with disabilities of 1:5, Thailand would need 60,000 special education teachers for the 300,000 students with disabilities currently being educated nationwide. These statistics underscore that the special educator shortage in Thailand is severe.

Lack of Knowledge and Skills

As noted earlier, special education teachers have reported that they lack special education knowledge and skills in providing instruction in inclusive classrooms; writing IEPs; teaching functional skills in addition to academics; handling severe behavioral problems; evaluating student performance; and transitioning their students to other related services and/or new schools (Chulalongkorn University, 2012).

These problems led to an issue which has never been raised in Thailand, special education teachers’ burnout. In addition to lack of knowledge and skills, a large number of teachers left the field because they had too many students enrolled in their classrooms; struggled with providing the intensive support that a number of students require; or had extra assigned administrative tasks leaving them less time for their direct instructional responsibilities. Other challenges identified for those in the field of education, including special educators, relates to the heavy demands for paperwork leaving less time for planning and teaching (Manager Online, April 26, 2013).

Lack of Resources

Unlike the United States where authors and their publishers are eager to market special education resources (e.g., textbooks) due to the high demand in the field, Thailand has only a few authors and no publishers who specialize in special education materials because “photocopied editions” are less expensive and publishing special education textbooks are unprofitable. High quality special education textbooks and other related materials written exclusively for special educators working in Thailand are rare. Consequently, students trained to be special educators depend solely on instructor lectures with instructors themselves possessing different levels of knowledge and skills related specifically to special education. Most textbooks currently in use are written only for the authors’ classes (e.g., Yodkhampang, 2004) or to satisfy professor tenure requirements. Future and current special educators have not had high quality resources to draw upon during their preservice education or for their continuing professional development.

OTHER FACTORS BEYOND SPECIAL EDUCATION

In Thailand, there are a number of other factors that more indirectly impact the field of special education and individuals with disabilities. Only some of these factors are discussed below.

Numerous Administrative Organizations Creating Confusion

In 1994, the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH, 2013) classified disabilities into five categories: Visual Impairments, Communication and Hearing Impairments, Physical and Mobility Problems, Mental or Behavioral Disorders, and Intellectual or Learning Disabilities. These five categories, however, were not found as helpful by the MOE for individualized education programming. Therefore, the MOE recategorized the various disabilities into an expanded nine category system by (1) dividing Communication and Hearing Impairments into Hearing Impairments and Speech and Language Disorders, (2) dividing Intellectual or Learning Disabilities into Intellectual Disability and Learning Disabilities, and (3) adding Autism and Multiple Disabilities (Kitdham, 2013). The Ministry of Social Development and Human Security (MSO, 2013) also uses its own seven disability categorical system which includes Visual Impairments, Hearing Impairments and Communication Disorders, Mobility or Physical Disabilities, Mental or Behavioral Disorders, Intellectual Disability, Learning Disabilities, and Autism. These differences in classification systems has created confusion for educators, parents, and individuals with disabilities themselves, and have become an obstacle for insuring a “seamless transition” in the provision of services for individuals with disabilities from preschool to school through adult services.

Clearly, the lives of people with disabilities in Thailand are impacted by three major governmental agencies including the Ministry of Public Health, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, and the MOE. Every baby and young child receives medical services and a disability diagnosis from personnel representing the Ministry of Public Health which includes pediatricians, psychiatrists, and psychologists. Parents of children with special needs who want to receive support and services from the government are required to “register” their children as “people with disabilities.” A “medical report” from a representative of the Ministry of Public Heath represents required documentation in order to secure a “disability identification card” which is necessary for children and adults to access health, special education, and adult services.

Disability registration represents another controversy in the field of special education in Thailand. The NSO (2013b) reported that, out of 1,871,860 people with disabilities in 2007, only 20% actually had a disability identification card. This low percentage can be attributed to individuals with less severe disabilities (63%), individuals whose parents did not want them to be associated with potential stigmatization (15.44%) discussed earlier in this chapter, and individuals who themselves or their parents were unaware of the need for disability registration (15.26%).

Formal versus Natural Support

In Thailand, it is difficult to determine whether formal support provided by the government or natural support coming from families and the community at large has a more significant impact on the lives of people with disabilities. As noted earlier, a large majority of the Thai population are Buddhists, and Buddhism stresses natural support to individuals with disabilities and their families. Although the Thai population generally believes people with disabilities and their families are paying back for past deeds, neighbors and other community members are almost always empathetic and supportive of these families. This natural or informal support from family and community members may in turn compensate for a lack of formal support from the government for families in rural areas. Unfortunately, most of the support that is characterized by empathy based on moral authority focus on “survival” rather than education or future development of the individual with a disability (NEP, 2013d; Thammarak, 2013).

Transportation represents another example of a factor impacting the lives of individuals with disabilities. Children with disabilities tend to have more medical appointments than children without disabilities. Public transportation, however, is available only in municipal areas, and this prevents these children from accessing available formal medical supports. It is more common that neighbors offer rides to and from hospitals to these families, particularly in emergencies. Another example relates to the provision of support in daily living activities. Many families of people with disabilities in rural areas of Thailand live in poverty, and it is even more challenging in single parent families. In many of these families, there are instances that a parent is ill, cannot work, has limited funds, and cannot cook for the family. In these situations, one or more neighbors always take action in one way or another to assist. One neighbor may give the family a small amount of money to one of the children to buy food for the family or share their own food while another neighbor may offer respite care, so the parent can rest (Viriyangkura, 2010).

Personal Outcomes Measurement

In the United States, personal outcomes for individuals with disabilities are measured in three areas including independent living, education, and employment. Government authorities in Thailand have used identical areas to assess outcomes. However, definitions and the relative emphasis of each area differ. For most Thai professionals, the concept of independent living refers to only basic human needs such as dressing and undressing, eating, cleaning oneself, toileting, and communicating needs. Independent living does not include higher level actions that are related to independent functioning such as moving around the community, speaking up for oneself, protecting oneself from danger or exploitation. Education typically refers to formal education from preschool to high school levels, whereas other types of education are ignored such as vocational programs and training courses provided post-high school or recreation classes. Education also emphasizes physical inclusion without a consideration of meaningful participation in class activities or social engagement. Employment represents another index of an important personal outcome. Most Thai people, however, do not believe that people with disabilities could contribute to society.

The perception that individuals with disabilities cannot engage in activities “normal people” do reflects low societal expectations. As is widely known, possessing low expectations may be reflected in their families doing everything for them, or teachers limiting how much they are taught; and this contributes to restricting their development. There are a number of documented cases in which high school students with disabilities were taught and found to be reading at the 6th grade level, although they had the potential to learn more. In addition to limiting opportunities to learn for individuals with disabilities, low expectations held for them by those with whom they interact leads individuals with disabilities to believe they have little control over their own life (an external locus of control), and self-fulfilling prophecy of low expectations contributing to eventual limited development.

Self-Determination

Although self-determination represents a major issue in special education in the United States, this concept does not exist in Thailand and was only occasionally alluded to in the literature. Jeerapornchai (2010) recently developed a program to enhance self-determination of students with mild intellectual disabilities in Grades 4–6. Unfortunately, the program focused only on decision-making skills that represent only one of many components of self-determination. Additionally, Jeerapornchai’s research results were interesting in that participating students earned only 19 out of 40 points (47.50%) before the intervention. Participating students with mild disabilities and attending general education schools exhibited weak decision-making skills.

Kosuwan (2012) also developed a training program to introduce the concept of self-determination and teaching strategies teachers could use to encourage students with intellectual disabilities to develop self-determination. Before the training program, the researcher measured the self-determination skills of 145 students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 9 and 12 as well as self-perception on self-determination of 330 special educators in special education schools in Thailand. The findings revealed that students possessed low levels of self-determination, although teachers reported that they had some knowledge of self-determination. Other than this study, the concept of self-determination has not been researched in Thailand. It is important, however, that this construct receive attention from policy makers, administrators, and practitioners in the field.

Quality of Life

Quality of life (QOL) has been considered one of the most important constructs in terms of its impact on one’s life. QOL for the population with disabilities in Thailand, however, is loosely defined as there is a lack of consensus on its definition. According to Schalock (2004), QOL refers to a set of factors reflecting personal well-being. QOL can be measured through a variety of indicators such as interpersonal relationships, social inclusion, personal development, physical well-being, self-determination, material well-being, emotional well-being, and the rights possessed by the individual. An example of this lack of a clear definition of QOL includes the National Office for Empowerment of Persons with Disability (NEP) whose responsibility is to focus on improving the QOL of people with disabilities in Thailand. According to the the Persons with Disabilities' Quality of Life Promotion Act, B.E. 2550 (2007) issued by the NEP, the promotion and improving QOL means “rehabilitating, providing welfare, promoting human rights, advocating, encouraging independent living to help this population live equally as a population without disabilities, live with dignity, fully and effectively participate in society in accessible environment” (Thai Lawyer Center, 2013, p. 1).

Bangkok Metropolitan city government, however, defines the term differently in its strategic plan to improve the QOL of people with disabilities. QOL is defined as “a perception of an individual on physical, mental, emotional, social, and environmental aspects of one’s life and ability to respond to one’s needs” (Bangkok Metropolitan, 2013, p. 7). Disability Support Services at Chiangmai Rajabhat University conducted a study on the QOL of college students with special needs, and only six areas were studied including food and nutrition, living arrangement, health, basic services, safety in life and property, and disability support services (DSS, December 3, 2012). Due to the different definitions mentioned above, it can be concluded that the QOL construct in Thailand needs further study and development.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Thailand has made progress in the field of special education over the past 20 years, but much work remains to more effectively meet the needs of individuals with disabilities. This opinion reflects the perspective of professionals who are familiar with special education in both Western countries and Thailand and is not meant to be critical of those familiar with the field only in Thailand. What follows is a list of recommendations that are intended to lead to the provision of more effective special education services for those with disabilities. These recommendations are based on the analysis of the current status of special education in Thailand provided earlier in this chapter.

Educate and Support Families

Because teacher performance should be continuously monitored, parents and families need to be educated and empowered. Parents and other family members of individuals with disabilities should also become more knowledgeable about their children’s disability, their care and characteristics of an effective special education program, as well as their children’s rights. Parents should also be empowered to serve as their children’s advocates, particularly developing effective communication skills to interact with teachers, administrators, and other professionals as well as learning strategies to report abuses without negative ramifications.

Equip and Encourage Special Educators

Although the MOE provides numerous training programs for special education as well as general education teachers each year, the quality of these programs should be assessed. Studies have confirmed that “one-shot” training does not work (e.g., Harwell, 2003). Rather, a long-term plan is needed to provide continuing education to special educators. In order to study the quality of training, a set of measurements such as pre- and post-training examinations, hands-on activities, observation in classrooms via face-to-face, video-taping, or videoconferencing should be in place to be selected from in order to eventually improve training programs.

Building learning communities within schools, creating mentoring programs, developing programs to provide special education technical assistance should be considered as well as strategies to reduce teachers’ administrative workloads. Completing paperwork and attending meetings also represent activities that take time away from teaching. Neither exclusively measuring student performance on standardized tests nor the extent of teacher compliance with policies and processes through document review are sufficient as measures of the effectiveness of special education services provided. Instead, instructional effectiveness must be evaluated based on a combination of criteria that are designed to maximize student learning.

To encourage special educators to provide appropriate educational services to students with disabilities, the MOE chose to use a financial incentive. Special funding allowances represent an effective motivator, but they are only one of many possible support strategies for special educators. Nonmonetary strategies should be used such as awards to recognize high performing special education teachers or productive working conditions (e.g., support from colleagues and administrators) that retain good special educators in the field.

Ensure High Quality IEPs – Curriculum, Strategies, and Evaluation

Every student with special needs requires an IEP. By having an IEP, the child is assured an appropriate curriculum (e.g., content to learn and progress at his own pace), appropriate instructional strategies (e.g., which instructional methods work best for this child), and appropriate evaluation (e.g., how to measure what the child has learned). Everyone involved with the child should participate in IEP process. Parents should become knowledgeable about and advocate for an IEP for their child. Most importantly, they must understand that an IEP is not only possible but desirable. Special education teachers should devote more time and efforts on IEP development and communicating with parents, other professionals, and students themselves if appropriate. School administrators should attend IEP meetings and ensure that the documents are prepared consistent with recommended practices. Finally, the MOE should enforce policies related to IEP development.

Improve Teacher Education

Thailand desperately needs more qualified special educators. Institutions of higher education should expand their special education programs to produce more students. In addition to increasing the supply of special education teachers, the quality of their preparation must also be addressed. Related to increasing the quality of the training of special educators, faculty members should be encouraged to expand their knowledge and skills in the area of special education. Efforts should also be directed toward retaining effective teachers. Teacher educators should also be encouraged to produce more special education resources (e.g., textbooks) in order to expand the knowledge base in the field. To achieve these goals, institutions of higher education must support their faculty through such means as grants for continuing education, incentives for writing, and encouraging their efforts in publishing textbooks and online media. At the same time, the MOE must also support these efforts. Finally, and most importantly, long-term policies to improve teacher quality should be developed.

Encourage Collaboration

Collaboration is critical for the success of students and teachers. Special educators need to work with general education teachers and other professionals. When students move to the next grade, special educators and general educators in both grades need to collaborate. Also, transitioning between services or moving into the different phases of their lives, students benefit from collaboration among responsible agencies under the three ministries in planning their services. With effective communication and collaboration, individuals with different roles and responsibilities and agencies would work as a team toward the same goal. They should also communicate with each other to align data and policies. This collaboration would produce increased and more accurate communication in the field.

Seek Long-Term Policy

Thailand has had 15 Ministers of Education in the past 16 years (Thaipublica, January 24, 2014). Frequent changes at this level have had a significant impact on policy and educational services for individuals with disabilities. To improve the quality of education for individuals with disabilities, education policies should be less influenced by political parties and politicians and more by needs in the field. This change would lead to more stability in policies and services for this vulnerable population of Thai citizens.

CONCLUSIONS

The field of special education in Thailand began in the late 1930s, and progress has been made over the last 80 years. Despite a number of improvements, the field of special education in this country still needs significant changes that require efforts from everyone involved to improve the quality of services and the lives of people with disabilities. Expanding the knowledge base, resources, teacher preservice education and retention, parent education and empowerment, effective monitoring systems, and long-term policies need continuous work. At the same time, Thai citizens must be educated to develop more positive attitudes toward disabilities in general and individuals who live with them.

NOTES

REFERENCES

Arrayawinyoo, P. (2001). An estimation of special education teachers demand. Retrieved from http://www.thaiedresearch.org/thaied/index.php?q=thaied_results&-table=thaied_results&-action=browse&-cursor=401&-skip=390&-limit=30&-mode=list&-sort=title+asc&-recordid=thaied_results%3Fid%3D6079

Bangkok Metropolitan. (2013). Development of quality of life of individuals with disabilities plan (2010–2011). Retrieved from http://203.155.220.230/info/Plan/Planacc53_54/plana53_54.pdf

BSE. (2011). History. Retrieved from http://special.obec.go.th/history_sss/thai.html

BSE. (2012). Development of education for individuals with disabilities plan (2012–2016). Retrieved from http://special.obec.go.th/download/19.9.55_Pland.pdf

Chandrakasem Rajabhat University. (2013). Thailand’s basic education. Retrieved from http://arit.chandra.ac.th/edu/Patiroob/education4.html

Chulalongkorn University. (2012). A study on professional autonomy in teaching. Retrieved from http://www.ksp.or.th/ksp2009/upload/ksp_kuru_research/files/2935-9862.pdf

Daily News. (2007, December 17). The new law forbids schools’ denial of children with disabilities. Retrieved from http://news.sanook.com/education/1/education_224731.php

Dhammaviteekul, A. (2009). Non-formal education. Retrieved from http://panchalee.wordpress.com/2009/05/17/non-formaleducation/

Dheandhanoo, C. (1992). The progress of Rajanukul hospital within 30 years. Rajanukul Journal, 7(1), 8–21.

DSS. (2012, December 3). Re: Asking for comments on research: Quality of life of students with disabilities at Chiangmai Rajabhat University (Facebook DSS group). Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/download/355925877837033/_ART_ART%20ART__%201-2.docx

FBTQ. (2013). About us. Retrieved from http://www.blind.or.th/en/about-us

FMRTH. (2013). About us. Retrieved from http://www.fmrth.com/about_us.php

Harwell, S. H. (2003). Teacher professional development: It’s not an event, it’s a process. Retrieved from http://www.cord.org/uploadedfiles/harwellpaper.pdf

IDEA. (2004). Individuals with disabilities education and improvement act (2004). Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov

Jeerapornchai, P. (2010). Developing a program to enhance self-determination on making decision skills of grades 4–6 students with intellectual disabilities. Doctoral dissertation, Srinakharinwirot University. Retrieved from http://thesis.swu.ac.th/swudis/Spe_Ed/Panichaka_J.pdf

Khun Poom Foundation. (2013). Khun Poom Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.give.asia/charity/khun_poom_foundation

Kitdham, P. (2013). Types of disability. Retrieved from http://sichon.wu.ac.th/file/pt-shh-20110120-171550-LGxcP.pdf

Komkris, V. (1989). Medical care of children with mental retardation to social integration. The 16th World Congress of Rehabilitation International, 14, 591–633.

Kosuwan, K. (2010). Intellectual disabilities. Nonthaburi, Thailand: Sahamit.

Kosuwan, K. (2012). The efficacy of teacher training program for enhancing knowledge and positive attitudes toward teaching self-determination to students with intellectual disabilities in special schools. Retrieved from http://educms.pn.psu.ac.th/edujn/include/getdoc.php?id=584&article=212&mode=pdf

Lopburipanyanukul. (2013). History of Lopburipanyanukul School. Retrieved from http://www.lopburipanya.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50&Itemid=29

Manager Online. (2012, December 4). The government approved an extra allowance for special educators. Retrieved from http://www.manager.co.th/qol/viewnews.aspx?NewsID=9550000147674

Manager Online. (2013, April 26). Policy of the Ministry of Education resulted lower quality of education. Retrieved from http://www.manager.co.th/Home/ViewNews.aspx?NewsID=9560000050418

Manager Online. (2013, July 6). List of inclusive schools. Retrieved from http://www.manager.co.th/family/ViewNews.aspx?NewsID=9540000082682

MOE. (2005). Population 6 years of age and over by literacy, age group, sex and area: 2005. Retrieved from http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCsQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.moe.go.th%2Fdata_stat%2FDownload_Excel%2FOutsourceData%2FLiteracyRate2548.xls&ei=vaXcUr3cC4e1i Qec0IBQ&usg=AFQjCNF6XlaotGN9fmXFItvMGWxcNCmy9w&sig2=wgpWjIxhi 7hdPAb3e6Fddg&bvm=bv.59568121,d.aGc

MOE. (2013). National education act 1999. Retrieved from http://www.moe.go.th/main2/plan/p-r-b42-01.htm#4

MOPH. (2013). People with disabilities rehabilitation act (1994). Retrieved from http://www.moph.go.th/ops/minister_06/Office2/disable%20law.pdf

MSO. (2013). Summary of social statistics 2013. Retrieved from http://www.m-society.go.th/edoc_detail.php?edocid=778

MUA. (2011). Current teacher education program. Retrieved from http://www.mua.go.th/pr_web/udom_mua/data/392.pdf

MUA. (2013). Royal Thai government gazette (June 8, 2009): Type and criteria for individuals with disabilities in education. Retrieved from http://www.mua.go.th/users/he-commission/doc/law/ministry%20law/1-42%20handicap%20MoE.pdf

Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University. (2011). General information on inclusive education. Retrieved from www.nrru.ac.th/web/special_edu/1-1.html#top

National Education Act, B.E. 2542. (1999). Retrieved from http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Thailand/Thailand_Education_Act_1999.pdf

NEP. (2013a). Thailand Constitutional Law (1997). Retrieved from http://nep.go.th/sites/default/files/files/law/6.pdf

NEP. (2013b). Thailand Constitutional Law (2007). Retrieved from http://nep.go.th/sites/default/files/files/law/2_1.pdf

NEP. (2013c). Education for individuals with disabilities act (2008). Retrieved from http://nep.go.th/sites/default/files/files/law/38.pdf

NEP. (2013d). Concept of disabilities. Retrieved from www.nep.go.th/upload/modResearch/file_4_tn-27-182.pdf

NSO. (2013a). The 2011 key statistics of Thailand: Social and cultural aspects. Retrieved from http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nsopublish/themes/files/soc-culPocket.pdf

NSO. (2013b). Number of people with disabilities by disability registration. Retrieved from http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nso_center/project/table/files/S-disable/2550/000/00_S-disable_2550_000_000000_03200.xls

NSO. (2013c). Number of persons with disabilities aged 5–30 years not attending school. Retrieved from http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nso_center/project/table/files/S-disable/2550/000/00_S-disable_2550_000_000000_00400.xls

NSO. (2013d). Number of persons with disabilities aged 15 years and over who do not work. Retrieved from http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nso_center/project/table/files/S-disable/2550/000/00_S-disable_2550_000_000000_01100.xls

OBEC. (2013a). Educational statistics report 2013. Retrieved from http://www.bopp-obec.info/home/?page_id=5993

OBEC. (2013b). Number of special education teachers in special education settings (2011). Retrieved from http://doc.obec.go.th/web/report/sum2_other1.php

Onkoaksoong, C. (1984). Exceptional children psychology. Bangkok, Thailand: Karnsasana Printing.