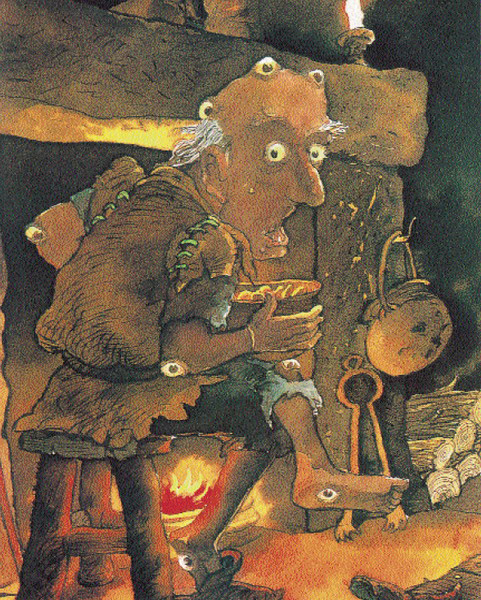

THERE WAS ONCE AN OLD MAN whose name was Eyes-All-Over, because that’s what he had. He had eyes in the back of his head, eyes on the top of his head, eyes on his elbows, and eyes on his knees. He even had one eye on the bottom of each foot.

‘Nobody ever catches me out!’ chuckled old Eyes-All-Over. And it was true, because each of his eyes could see different things.

The eyes in the back of his head could see things that happened yesterday. The eyes on the top of his head could see things that happened a long way away. The eyes on his elbows could see everyone else’s mistakes. The eyes on his knees could see everyone else’s hopes. And the eyes on the soles of his feet could see things that would never happen.

Now the only thing in the whole world that old Eyes-All-Over really cared for was a pot of gold that he kept under the floorboards in his bedroom. Every night he would close all the shutters, draw the curtains, take out his pot of gold and count it – just to make sure it was all there.

And as he counted it, the eyes on the top of his head looked around to make sure no one was peeping in – while the eyes in the back of his head made sure the coins were the same as they were yesterday.

Every week his pot of gold would get larger, because, whenever he went to market, the eyes in his elbows spotted everyone else’s mistakes – so, if someone were selling a pig for a pound that was really worth three, old Eyes-All-Over would snap it up and sell it again as quick as fat in the frying-pan!

And, of course, old Eyes-All-Over never warned anybody they were making a mistake or that they’d lose their money. Oh no! He was far too busy thinking about adding all those golden guineas to his pot of gold.

Well, one day, Eyes-All-Over was sitting at home, counting through his pot of gold as usual, when suddenly there was a knock on the door.

‘Burglars!’ he exclaimed to himself. Then he thought: ‘No… wait a minute… burglars wouldn’t knock on the door. They’d just climb down the chimney.’

So he carefully hid away his pot of gold, and then he opened the door – just a crack.

There on the step stood a thin girl who said: ‘I’m hungry and I have nowhere to live. May I do some work for you to earn a slice of bread and dripping?’

‘Bread and dripping!’ exclaimed old Eyes-All-Over. ‘D’you think I’m made of money?’

‘I could clean your house or chop your wood for you,’ said the girl.

‘Listen!’ said Eyes-All-Over. ‘The eyes in my knees can see what you’re hoping – you’re hoping to be rich one day and live in a nice house like this! Why, you’d probably cut my throat while I’m asleep! Be off with you!’

‘Oh no!’ said the poor girl. ‘I’d never do a thing like that!’

Well, old Eyes-All-Over slyly slipped off a shoe and looked at the girl with one of the eyes in the soles of his feet – the eyes that could see things that would never happen. He saw at once that she would never do anything to harm anyone.

‘Hmm! Very well,’ he said. ‘I do need some firewood chopping.’

So the girl chopped some firewood, and he gave her a piece of bread (without any dripping) and let her sleep that night in the woodshed.

The next day, old Eyes-All-Over woke up to find his house clean and neat and a breakfast of beans and ham waiting for him on the table. For the girl (whose name was May) had been up working hard for several hours already.

So Eyes-All-Over gave her another piece of dry bread and said: ‘You can stay another day.’

Well, May stayed and worked for old Eyes-All-Over for some years. In return he let her sleep in the woodshed and allowed her to eat one piece of bread in the morning and one bowl of soup at night. ‘Eh, eh!’ he used to grin to himself.

‘She costs me nothing and she works as hard as six men. What a bargain!’

One day, however, a stranger was riding past the house, when he caught sight of May digging the cabbage patch. She was still dressed in the same rags she’d been wearing when she first arrived (for it never occurred to old Eyes-All-Over that she might need new clothes) and she was exhausted from all her hard work, but even so May looked so beautiful that the young man fell in love with her on the spot. And, not long after, she fell in love with him.

So the young man went to Eyes-All-Over and told him that he wanted to marry May.

Now old Eyes-All-Over saw at once that he must be a rich young fellow. ‘Eh, eh!’ he thought, ‘I can make a good bargain out of this business!’

But he put on a sad face and said: ‘Oh no! You can’t take young May away from me! She cooks my breakfast every morning!’

‘Very well,’ said the young man, ‘take this.’ And he handed old Eyes-All-Over a ruby ring. ‘With that you can hire the finest cook in the world to make your breakfast every day!’

But old Eyes-All-Over slyly looked at the young man with the eyes in the back of his head – the eyes that could see things that had happened yesterday – and he could see that only yesterday the young man had bought a fine fur coat. So old Eyes-All-Over screwed up his face and looked very sad and said: ‘Oh, young sir, you don’t really mean to take young May away from me? Don’t you know she cuts my wood every day and makes my fire … I’d need a fine fur coat to keep me warm, if you were to take her away from me.’

So the young man went and fetched the fine fur coat, which he had actually bought for his father, and gave it to old Eyes-All-Over.

‘There,’ he said. ‘Now may I marry May?’

But old Eyes-All-Over looked with the eyes on the top of his head – the eyes that could see things that were happening far away – and he could see that the young man’s father, who was waiting for his return, lived in a fine palace, surrounded by fabulous wealth.

So Eyes-All-Over took out his hanky, and pretended to cry salty tears into it.

‘Oh, good sir!’ he said. ‘You cannot possibly want to take young May away from me! She works so hard and keeps my house so neat and clean. Why! She’s worth her weight in gold!’

So the young man rode off and returned, some time later, with a chest filled with gold pieces that altogether weighed exactly the same as young May.

‘Now,’ he said, ‘May and I must go and be married.’

But old Eyes-All-Over hadn’t finished yet. ‘I can still screw even more out of this bargain!’ he said to himself. Then he looked at the young man with the eyes in his knees – the eyes that could see people’s hopes – and he could see that the young man had hopes, one day, to be a king – for he was, in fact, a prince.

So old Eyes-All-Over clutched his heart and said: ‘Ah! Good sir! Would you take this child from me? She has been like a daughter to me these many years. I would not part with her for half a kingdom!’

‘Very well,’ said the Prince, and there and then he signed away half his kingdom to old Eyes-All-Over. Then he lifted May up onto his horse, and they rode off together – to be married with great feasting and merry-making in his father’s palace.

As they rode away, old Eyes-All-Over rubbed his hands with glee.

‘What a bargain!’ he said to himself. ‘I get all those years of work out of that thin stick of a girl, and then I sell her off for jewels and furs and gold and half a kingdom! I certainly am the sharpest chap around!’

But, at that very moment, he looked at himself with the eyes in his elbows – the eyes that saw people’s mistakes – and he saw, to his horror, that he himself had made a big mistake, though he didn’t know what.

As he got his lonely breakfast, however, and sat by his lonely fire, he began, to realize what it was, for he found himself longing to hear May’s voice singing in the garden and to see her face across the room. Soon he found himself thinking that he would give back everything just to have May give him one of her smiles.

But, when he looked at himself with the eyes in the soles of his feet – the eyes that saw things that would never happen – he knew she would never smile at him again.

And this time, old Eyes-All-Over cried real tears, for he suddenly realized that – when he gave May away – he’d given away the only thing he’d ever really loved.

And he cursed himself that – all the time she’d lived with him – he’d given her nothing but hard words and hard work, and had never given her any reason to care for him.

And old Eyes-All-Over then saw – clearer than anything he’d ever seen in his life – that despite having eyes all over, he had really been quite, quite blind.