The Western Front was opened when the Germans attacked Luxembourg on 2 August 1914, and Belgium the following day, according to their great Schlieffen Plan that they had been plotting and perfecting for almost two decades. Among other things, Schlieffen had been anxious to avoid making a frontal attack on the impressive chain of modern frontier fortresses that blocked the direct path into north-east France in the area between Verdun and Belfort. These fearsome bulwarks had originally been planned after 1871, mainly by the great engineer General Serré de Rivières, and some of them had been upgraded successively as technology advanced. The Germans’ assessment was therefore that, when compared with a frontal assault upon those fortresses, the diplomatic sin of breaking Belgian neutrality represented very much the lesser of two evils. However, the Belgians also had their own brilliant fortress-builder, in the shape of General Henri Alexis Brialmont. He had laid out rings of fortification around Antwerp, Liège and Namur that had originally been no less modern than those to be found on the French side of the Ardennes. The German leadership did not expect the Belgians to offer any resistance at all; but the reality in 1914 was that the new King Albert was defiant. His fortresses would indeed try to block the German advance, and they promised to negate the Schlieffen Plan completely. If they had succeeded, it is possible that this particular world war would have fizzled out very quickly indeed.

For every new type of fortress, however, a new means of attack would eventually be designed. In this case the Germans had some excellent heavy 210mm howitzers, which from 5 to 16 August pounded the key fortress of Liège into submission within a quite unexpectedly short space of time (see table) in an operation which incidentally rocketed a certain Colonel Ludendorff to the fame and glory that would give him the supreme command in the west as early as August 1916.

The shells came crashing through the thick concrete roof of enough of the 12 ring forts to cause a general collapse of resistance. They exploded with devastating effect inside the garrison’s living quarters, numbing the survivors with the concussion and choking them with swirling, blinding dust. As if that were not enough the Germans then produced an even higher trump card, in the shape of new super-heavy siege artillery: the Krupp 420mm ‘Big Berthas’ or ‘Gamma guns’, and the Skoda 305mm ‘Skinny Emmas’ or ‘Beta guns’. All the forts at Namur and Antwerp were attacked with 420 or 305mm projectiles, and they also fell in short order. For a heady moment it looked as though all Schlieffen’s fears about the power of modern fortification had been misplaced, and that the German offensive would be completely unstoppable. This seemed to be doubly true when the defeat of the Belgian forces was followed by that of five French and one British armies in short order in the ‘battle of the frontiers’ between 20 and 25 August. At Charleroi the French Fifth Army was able to hold its positions for only three days in the face of heavy shelling, while at Mons the British were outflanked and forced to retire after only 12 hours. Still the Germans advanced, and still they were able to capture forts at Lille and Maubeuge apparently at will, and then the particularly modern Fort Manonviller in Lorraine on 27 August. Nor was the German advance finally halted on the Marne by the tactical power of the defence, but rather by skilled French re-deployments combined with German mistakes at the operational level.

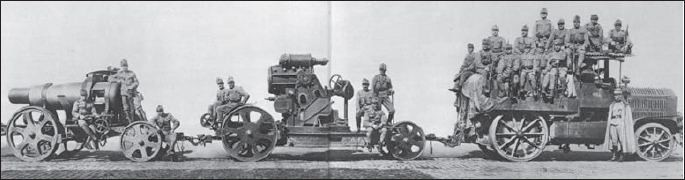

A ‘Skinny Emma’ Austrian 305mm fort-busting siege mortar in the travelling mode. These guns performed great feats in helping to destroy the Belgian and Maubeuge forts in 1914, and would see much action again at Verdun in 1916. (The Illustrated War News, 1914)

A destroyed cupola at Fort Loncin at Liège, after only a short bombardment by the German heavy artillery in August 1914. (The Illustrated War News, 1914)

Where the tactical defensive really came into its own was in ‘the race to the sea’ as both sides staked out long frontages with relatively small numbers of men. After just a few hours’ improvised entrenchment these thin screens often proved capable of unexpectedly robust, albeit still very costly, resistance. First the Germans took up positions along the Chemin des Dames on the north bank of the river Aisne which they would hold until 1918. Then the allies outflanked them to the west, to be met in turn by more German lines, which eventually reached the sea just north of the Belgian border in mid-October. Finally, the Germans attempted a series of counter-attacks on the northern end of the line, from 20 October to 24 November, which would become known as the battle of First Ypres. The Belgians on the left flank fought well and retired under the cover of innundations, while the British on the right, around Ypres itself, managed to hold their positions by desperate expedients, despite three potential German breakthroughs. Every man who could be scraped together was thrown into the cauldron, protected by the flimsiest of fieldworks and with all too scant training in the essentials of modern tactics. Nevertheless, the allied line held firm and General Haig won the fame and glory that would secure him command of the whole BEF as early as September 1915.

Naive British troops in October 1914 in a nicely narrow trench that is well built with regulation parapet and parados more than covering a standing man, and with no enemy threat in sight. However, it is a death trap by reason of its overcrowding and almost complete lack of traverses – nor do there seem to be either firesteps to allow the men to use their rifles, or revetments to prevent the walls crumbling in rain. (The Illustrated War News, 1914)

As the armies settled down to trench warfare, they rapidly discovered that their pre-war ideas about field fortification were outdated in many important respects. In the first place they could not afford to pack men into the front line in the old ‘shoulder to shoulder’ manner: not only because the frontages were now so long that they could be held only if the manpower was spread very thinly, but especially because modern artillery made it suicidal to bunch together, even when protected by earthworks. A single lucky shell could wipe out all the inhabitants of any given section of trench, so a strict system of zigzags and ‘traverses’ had to be introduced to ensure that each trench section was short enough to be held by at most only one man. For the same reason it was quickly appreciated that not even the best-built trench was sufficient for full protection. Shell-proof underground dugouts became absolutely essential for security, and their construction came to be given a much higher priority than the trenches themselves.

Secondly, barbed wire turned out to be of enormous importance in strengthening any defensive position, and tens of thousands of miles of it began to be strung out all along the front. Wiring parties would venture forward into no man’s land every night to hammer in wood or metal pickets – or more silently to screw in specially designed steel ones – and then connect them together with reels of wire, making it far harder for an attacker to reach the defended trenches without revealing his presence. Less obvious, but equally voracious of engineer stores, was the massive use of telephone cable, to link the front trenches to their commanders at battalion and brigade HQs, and then to higher headquarters all the way back up the chain of command to the army chief of staff and his vastly proliferating logistic agencies.

Naive German troops in October 1914, hopelessly overcrowded in a trench that does at least have traverses and good firing positions, but which appears to be too shallow to conceal a standing man, and seems to lack a parados. Note the steel loophole shielding the machine gun: similar loopholes would be a common item of German trench furniture through much of the war. (The Illustrated War N ews, 1914)

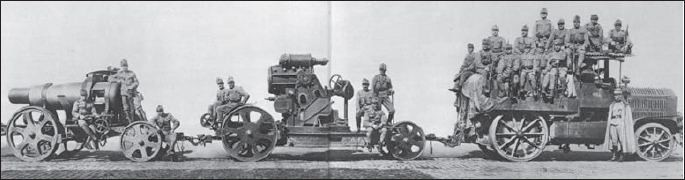

Deep fire trench with overhead cover. In 1914 there was a belief in the British army that the only overhead cover required was a relatively shallow covering (9–12in.) to absorb shrapnel. The shock of battle soon showed this to be not only unrealistic but positively damaging, since the debris from collapsing roofs would often block the trench to traffic. Only much thicker overhead cover was useful against HE shells. (The Museum of Lancashire: Solano manual, 1914 – p. 92, Fig. 51)

Thirdly, it soon became clear that the pre-war armies had been equipped mainly with direct-fire weapons for warfare in the open – light field guns, machine guns, rifles and bayonets – rather than with the type of indirect-fire weapons that were really needed to fight in trenches. For trench warfare the requirement was for HE munitions that could be made to fall into the enemy’s positions vertically from above, to explode below ground level in the places that could not be reached by horizontally flying or ‘grazing’ bullets. Howitzers were ideal for this new requirement, and it was unfortunate for the allies that in 1914–16 the Germans enjoyed a great numerical lead in that particular department. Trench mortars represented a smaller but novel version of the howitzer, and all armies had to improvise their own new designs during the course of 1915, sometimes using such primitive expedients as elastic band catapults or medieval-style trebuchets. At a level below that there was also a need for rifle- and hand-grenades that could be used by individual infantrymen. Once again, few suitable munitions were readily available on the inventory, so new ones had to be created during the year. It would be only in 1916 that fully combat-proven and soldier-proof mortars and grenades (or ‘bombs’) would be available to all.

Fourthly, and perhaps less obviously to the generals of 1915, the need for defence in depth gradually came to be appreciated. Despite the very many bloody defeats suffered by attacking forces, it remained a fact that absolutely any trench, no matter how well built or armed, could always be captured if the assailant was sufficiently well prepared, determined and organised for the task. The rapid German advance through Belgium had shown that even fixed masonry fortresses could be taken quickly, provided the attacker was appropriately armed; and in late 1914 and 1915 it turned out that the same also applied to field fortifications. At Neuve Chapelle on 10 March the British achieved a near-breakthrough, albeit on a short frontage, using an especially heavy ‘hurricane bombardment’ with artillery to destroy the enemy front line trenches before the infantry moved into them. At Second Ypres on 22 April the Germans made a small but spectacularly successful attack with poison gas, adding yet another category of weaponry to the fast-expanding inventory. Then the French Captain Laffargue was able to demonstrate great initial success in May at Neuville St Vaast, using only infantry equipped with a suitable mix of the new generation of man-portable weapons, although even he – and later the rest of his brigade – was eventually halted by just two machine guns located in depth. The manual that he wrote as a result of this experience (translated by the British as CDS 333 in December 1915) was circulated in every army and can be hailed as the basis of what would later be called ‘storm troop tactics’.

Gordon Highlanders carrying wire at Tilloy les Mofflaines, May 1917. Note the methods of carrying and deploying it. (Imperial War Museum, Q 5230)

Since they knew that no trench was really secure from capture by a well-prepared assault, every general who wanted to make an attack was naturally encouraged to believe that offensive warfare was still perfectly possible: and all too many lives would be lost in pursuit of this belief. The problem, however, was that the generals who wanted to defend – and usually they were Germans – quickly realised that it was essential to build a second system of trenches a mile or two behind the first system, so that even if the first line were captured, the attacker would not be able to break through to the defender’s rear areas. In other words a break-in should not be converted into a break-out. There was no break-out at Neuve Chapelle, Second Ypres or Neuville St Vaast, nor on many other battlefields besides, simply because the act of capturing an enemy’s front line completely disrupted the attacker’s communications and artillery support. Hence all attempts by the attacker to improvise an immediate second bound forward could be countered by an even more immediate second line of resistance improvised by the defender. The result was that by the end of 1915 a second line of defence, and sometimes a third and even fourth, had become standard along the whole of the Western Front.

In February 1916 the Germans launched a carefully planned offensive against Verdun, which encountered two distinct layers of defences. In the front line there was a system of fieldworks that had been built to a high standard in 1915, including some early concrete shelters. Resistance continued for some time along this line, but so powerful was the German assault, especially in terms of artillery, that the front eventually succumbed. Behind it lay the fixed pre-war forts, some of which had been almost ‘state-of-the-art’ in 1914, and capable of resisting even the now-ageing super-heavy howitzers that had reduced Liège and Namur. Unfortunately by 1916 these forts had largely been stripped of their garrisons, and even much of their artillery, due to the pressing needs of the front line. Thus is was that just nine German infantrymen, who had fought their way through the advanced fieldworks, were able to wander unopposed into Douaumont, ‘the strongest fort in the world’, on 25 February. Douaumont had been all but undefended, and in German hands it would quickly become a stalwart bastion against French counter-attacks. The second and last of the Verdun forts to fall was the considerably smaller Fort Vaux; but in that case the French had been forewarned and were able to put up a ferocious resistance – mainly in gas-filled, lightless underground tunnels – which lasted for almost a week, from 2 to 7 June. It was an epic of defensive warfare that would inspire the post-war Minister of War, the ex-sergeant André Maginot, to build the ultra-modern fortified line along the whole Franco-German frontier that would forever bear his name.

Colonel Driant’s HQ bunker at Verdun, which would be a surprisingly early example of an ‘improvised’ concrete fieldwork, had it not been pre-planned as a part of the highly sophisticated system of defences to support the main pre-war forts. Driant himself had been a celebrity of the French extreme political right before the war, and his death in the February 1916 fighting quickly achieved iconic status among ‘patriots’. (Paddy Griffith)

The author stands on the counterscarp of one of the forts on Bois Bourrus ridge at Verdun, 1965. The undergrowth was already very thick then: it has become much more so during the intervening 40 years. (Paddy Griffith)

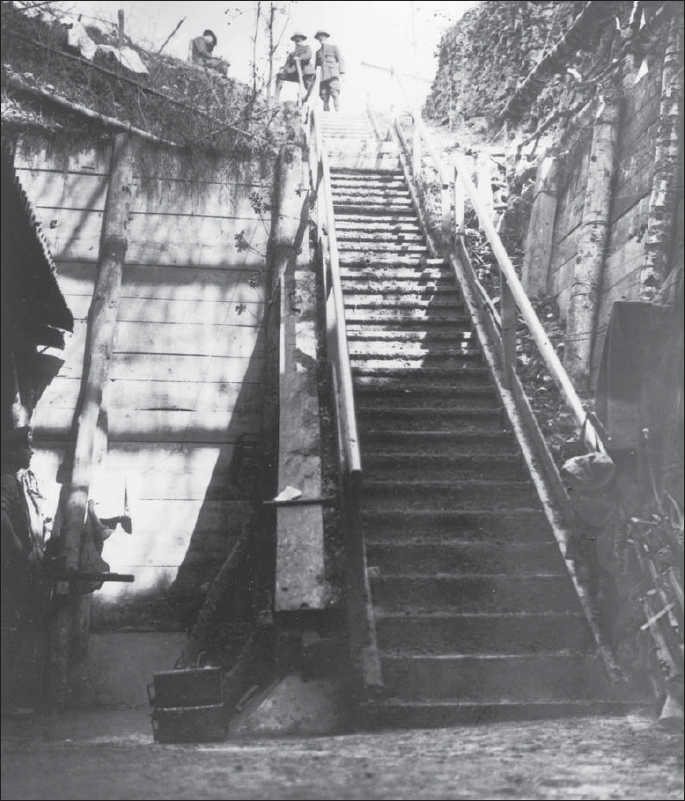

After the German impetus had been halted, the initiative passed to the now numerous, but still inexperienced, British on the Somme from 1 July onwards, and then eventually to the French at Verdun, who began to counter-attack on 19 October. What the British encountered was a system of fieldworks that was even stronger than any that had so far been seen. Not only were they laid out in depth, all the way back up the slope from the original front line, in low ground, to the overwatching features of High Wood and Delville Wood, but each line of German trenches was dotted with deep shelters, or Hangstellung, often well over 20ft below ground level. Large numbers of troops could rest within them in complete security from all but the very heaviest shells, whereas at only 6 or 8ft deep the trenches and light shelters on the surface were always vulnerable to artillery and trench mortars. They would be very thinly held, and usually very poorly maintained in normal times. At moments of crisis, however, a seemingly endless file of fresh troops could emerge from their deep shelters to strengthen a threatened point, or launch counter-attacks. At first the allied troops were awed and bewildered by the presence of these unexpected German reinforcements and then, once the secrets of the deep dugouts had been uncovered, they allegedly became angered that their own engineers had not provided them with similarly secure accommodation.

On the flank of the glacis of Fort Vaux, Verdun: a steel observation turret peers over its massive concrete mounting, with the remains of a wrecked twin 75mm gun cupola to the left and in front. (Paddy Griffith)

It soon became clear on the Somme that this new generation of German defences could not be physically destroyed by shell fire, as they had been at Neuve Chapelle, since there simply were not enough guns available to bring down a sufficient weight of HE per square yard. Instead, it was realised that the best tactic was to use artillery merely to neutralise the German defenders for the relatively short period needed for attacking infantry to get in among them. This concept became crystallised as the ‘creeping barrage’, which had been poorly understood on 1 July, but which was being used widely from 14 July onwards. As it developed in late 1916 through 1917 the mature British creeping barrage would become a fearsome weapon indeed, with up to seven successive lines of bursting shells, mortar bombs and machine-gun barrages, ranged up to one and a half miles in depth, advancing regularly by 100 yards every four minutes in step with the advance of the infantry line. The aim was to make it so dangerous for a defending infantryman to raise his head above the parapet that he would prefer to stay sheltered in underground burrows. He would then be unable to bring fire to bear against attacking infantry until it was too late.

By the end of the Somme battle in November, the Germans had been forced to build no less than seven successive defensive lines in depth, which had eventually stymied all of the many attempted breakthroughs to Bapaume, whether by infantry, cavalry or even, on 15 September, by tanks. It still remained true that a well-organised and well-prepared attacker could always capture the first line of trenches – especially when he was following a creeping barrage, and using Laffargue-style platoon tactics whenever the barrage broke down. However, once the allies had captured the first defensive line, the Germans at both Verdun and the Somme were adept at re-capturing it by an instant counter-attack, or at least at falling back to their next position in depth, to pose a huge new logistic problem to a would-be assailant.

The problem with immediate counter-attacks was that they normally cost a high toll in casualties, even when they succeeded. Because of this, both Verdun and the Somme were fought at exceptionally high intensity, and in human terms they turned out to be as damaging to the Germans as to the allies. At the end of it all the German high command was forced to re-think its defensive tactics once again, as a result of which they adopted a wide range of significant new measures. In the first place they knew they urgently had to save manpower, so in early 1917 they shortened their line in the west by making a strategic step back of up to 30 miles from the Noyon salient, between Arras and Soissons, to the central section (out of five) of their newly built Hindenburg Line, or Siegfried Stellung. Among other things they abandoned the town of Bapaume, for which they had fought so hard in the previous year. In terms of defensive technique their retreat was the first occasion on which a modern army employed a systematic policy of scorched earth, including the widespread use of booby traps (as well as stay-behind machine-gun teams) to deter a rapid pursuit. This practice would become standard in the autumn of 1918, and then throughout World War II.

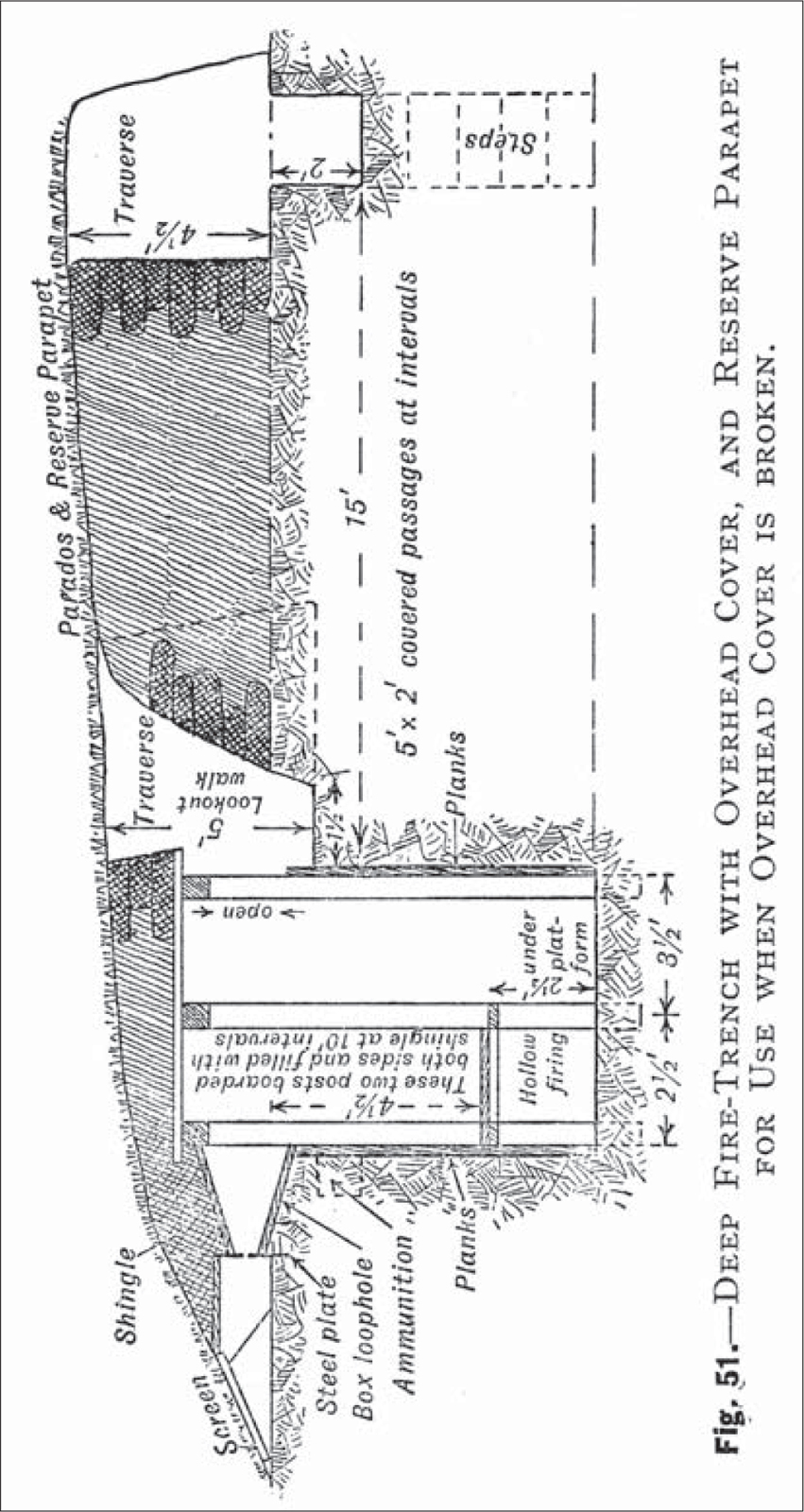

Entrance stairs from a German deep bunker captured by the 9th Scottish Division at the north end of Bernafray Wood, 3 July 1916. At this period of the war the British were often amazed and awed at German industry in digging such deep and well-funished dormitories. (Imperial War Museum, Q 4307)

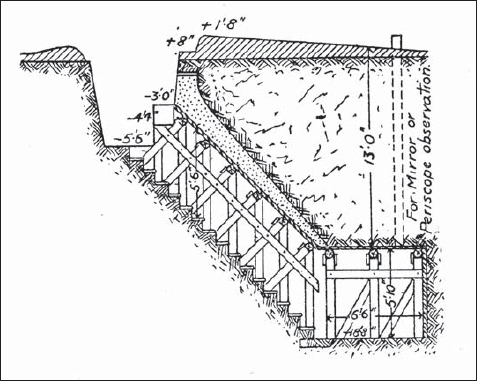

German diagram of the entrance to a 19ft deep dugout. Note the great care taken to reinforce the roof of the staircase with concrete, to help prevent collapses. There was also provision for a 14in. periscope, as was recommended for most German dugouts at this time – but which was rarely seen in practice. (Museum of the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment: German 1916 manual on field positions – p. 22 Fig. 14)

The unexpected German retreat delayed the allies; but the British were able to attack Vimy Ridge and Arras on 9 April, while the French launched their much-trumpeted ‘Nivelle Offensive’ on the Chemin des Dames on 16 April. Unfortunately, neither attack led to the clear breakthrough that had been promised, and Nivelle’s efforts were so spectacularly unsuccessful that the French Army fell into a mutinous state throughout the summer. This shifted the main weight of the war onto British shoulders at long last, although Field Marshal Douglas Haig was doubtless ill advised to make his next assaults in the area of the Ypres salient. This was a particularly unpromising battlefield, with dreadful weather, worse drainage and overlooked from three sides by German positions. General Friedrich Sixt von Arnim had also made some serious improvements to his defences, including a layout in great depth that featured the extensive use of concrete machine-gun nests, troop shelters and command posts. The initial attack at Messines on 7 June went well enough, with the help of 19 mines using a total of a million pounds of high explosive; but the main Ypres offensive on 31 July enjoyed much less success. Despite their great superiority in artillery the British made very slow progress and managed to capture the final crestline at Passchendaele village only on 6 November.

As a final footnote to the year’s operations Haig authorised a relatively small ‘raid’ on a weakly garrisoned section of the Hindenburg Line outside Cambrai on 20 November. This attack had originally been planned as a demonstration of the new artillery technique of predicted fire, to which tanks were later added to crush the deep wire entanglements. In the event surprise was complete and advances of five miles were achieved over previously uncratered ground. But once again there was no break-out, since the Germans were able to occupy depth positions in time, after which they re-took much of the captured ground by a major infantry counter-attack on 30 November.

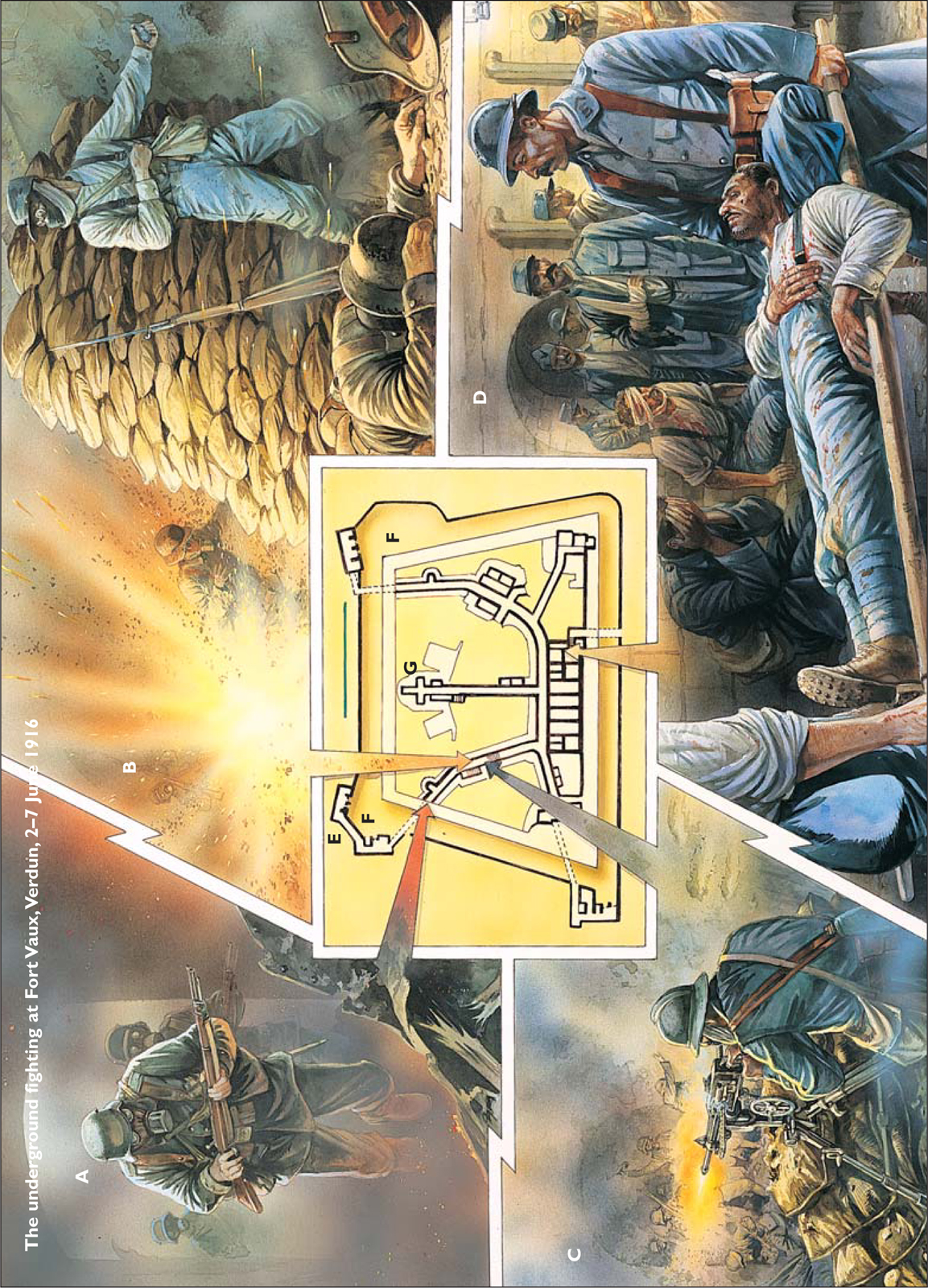

The underground fighting at FortVaux, Verdun, 2–7 June 1916

Vaux was the pre-war French fort that achieved more than any other against German attack, when its variegated 600-man garrison under Major Sylvain-Eugène Raynal – many of them already wounded or sick – managed to put up a stupendous resistance that would inspire post-war planners. The defenders first disputed the main ditch with machine-gun fire from the counter-scarp galleries, and then held a succession of improvised barricades in the underground corridors leading to the centre of the fort. The Germans, commanded by Lieutenant Rackow of the 158th Paderborn Regiment, were subjected to murderous shelling while they remained outside the fort, but could make little headway inside it. Their flamethrowers were ineffective and caused many losses to the attackers themselves, although their smoke certainly added an extra dimension to the swirling cement dust, HE fumes and human decomposition odours that already pervaded the inner corridors. In the event it was only thirst that eventually forced the garrison to surrender, with a loss of no more than 100 casualties as contrasted with some 2,742 Germans.

A) German pioneers destroy steel doors with bundles of grenades, to gain access to the corridor leading from the counter-scarp galleries to the interior of the fort.

B) The underground corridors were held by a series of sandbagged barricades manned by individual grenadiers or machine gunners, who had to fight in pitch darkness. These men sold their lives dearly and succeeded in reducing German progress to a snail’s pace.

C) On 4 June the Germans attempted a flamethrower attack, which temporarily silenced the defenders, but Lieutenant Girard leapt back heroically to man a machine gun in the northwest corridor in the nick of time, and although he was soon wounded, he did manage to beat off the assault.

D) The main barracks in the heart of the fort were crowded with sick, wounded and other non-combatants, and the first-aid post was always busy. On the level below the accommodation there was a lower level for stores and the (tragically under-filled) water cisterns.

E) Double gallery for machine guns covering the main ditch. These guns did great execution on the attacking troops on 2 June before they were eventually suppressed by hand grenades.

F) The main ditch.

G) The 75mm gun cupola, which had been the only offensive armament of the fort before it was destroyed by a super-heavy shell early in the Verdun battle.

The Cambrai counter-attack demonstrated the new German ‘storm troop tactics’, which were essentially the same as those described by Laffargue as early as May 1915, and then incorporated in British manuals in February 1917. These tactics were applied less completely by the Germans than by the allies, and with far fewer resources in depth; but at Cambrai and then against Gough’s Fifth Army in the St Quentin offensive of 21 March 1918, they were particularly fortunate to encounter badly deployed and undermanned British defences. The actual weakness of the German assault tactics was well demonstrated by their totally futile attacks against Byng’s Third Army, also on 21 March; but it is their spectacular victory against Gough that is most remembered by history. The result of this attack was to break quickly through a fragile British front line, and then disrupt the scarcely existent ‘trace trenches’ of the second and third lines. Although the German infantry soon outran its own artillery and logistics, the spearheads were able to infiltrate between and behind such solid fragments of resistance as they encountered, pushing westwards as much as 40 miles in 15 days. It was only then that they encountered a continuous line of resistance that they could not break, and so their commander, Ludendorff, made a series of new but ever-weakening thrusts in other directions. On 9 April a new break-in was made on the Lys, and on 27 May a third on the Aisne, followed on 9 June by a fourth towards Noyon-Montdidier, and on 15 July a fifth on either side of Reims. After that the German assault troops were left exhausted, badly dug in for defence, and lacking many of the supplies they had previously enjoyed in plenty. The initiative gradually passed to the French and the first fighting formations of Americans, who together had already held the line at Château Thierry and Belleau Wood and who had begun to mount a series of counter-attacks as early as June. On 18 July they landed a particularly telling blow near Soissons, assisted by large numbers of tanks.

Then at Amiens on 8 August the British started their own all-conquering ‘Hundred Days’ offensive, with French support to the south, at first against the relatively weak positions which marked the high tide of the German advance. The attack gathered momentum during the next few weeks as the enemy was successively bundled out of the Péronne Line and then all the way back to the more formal fortifications of the Hindenburg position along the St Quentin canal. At the end of September a set piece attack was launched against this line, complete with a full-scale artillery bombardment. It was entirely successful and the pace of the allied advance accelerated until the armistice on 11 November, 100 miles beyond the start line of 8 August. This represented a rate of advance that was almost as spectacular as the German march to the Marne in August 1914, and it once again seemed to suggest that fortification and the defensive were less powerful than people had imagined.

Meanwhile the French and Americans set about clearing the St Mihiel salient, south of Verdun, which was achieved against surprisingly light opposition between 12 and 16 September. Then the Americans had to make a rapid relocation for their next effort, as early as 26 September, to strike north-west of Verdun into the Meuse-Argonne region, which the Germans had carefully fortified in depth from 1916 onwards. This proved a very tough nut for the inexperienced US forces to crack, and it was only at the start of November that they were able to accelerate beyond Monfaucon and the Argonne Forest towards Sedan and the line of the Meuse. Further to the west the French were advancing across the Aisne from the area of Reims towards the Meuse around Mezières, which they also reached by the time of the armistice.

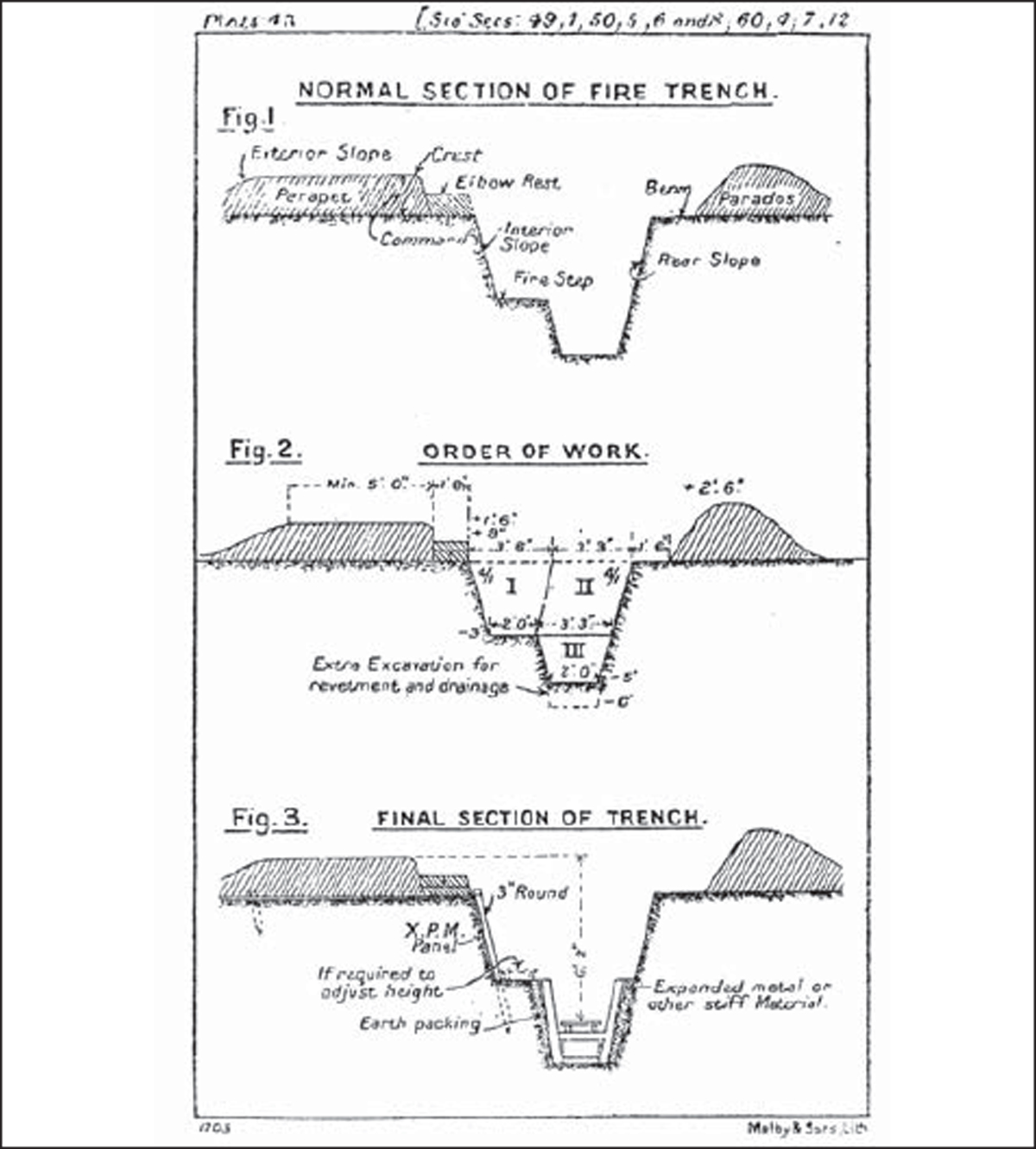

The ‘vital statistics’ of a basic fire trench, including parapet, parados and arrangements for revetment and drainage channel beneth the duckboard walkway. (The 1925 British General Staff Manual of Fieldworks – plate 48)