Essentially the battlefield sites on the Western Front today come in four types:

1) The cemeteries and monuments, almost all of which were built after the war, and which therefore need not concern the modern student of the war itself, unless it is for purposes of family remembrance. Note, however, that some of them do actually include original fortifications, for example the concrete shelters in the German cemetery at Langemarck and in the British cemetery of Tyne Cot, which includes one that is 98 per cent buried under the central pure white stone cross of sacrifice.

2) The fields, woods, villages and contours that originally shaped the layout of fortifications and tactics in 1914–18 were speedily and lovingly restored after the war to more or less their original pre-1914 form. We can only admire the skill and energy of the good people who did it. They have allowed us to re-visit the battlefields in at least a distantly recognisable form, and to understand many of the intricate terrain relationships that determined the course of the fighting. It should nevertheless be mentioned, alas, that in the process they have often buried or destroyed a good proportion of the archaeological evidence for the trace of the fortifications, as well as many of the fortifications themselves. It is only in a good light at certain times of the year, and often only from a light aeroplane, that a comprehensible pattern of the trench lines is revealed from below the surface of the ploughed fields. There are also some significant areas that remain inaccessible to the view of the modern tourist, because they are either privately owned woods, or have been built over by modern suburban sprawl.

3) The above-ground fortifications that survive may be found either where they have been deliberately preserved as monuments, or where no one has seen any particular reason to remove them. Most of the pre-war forts are still there and are by far the most spectacular examples of 1914–18 fortification that can be visited, even though they are usually in a distinctly battered state, and often in the notorious ‘private woods’ (a surprisingly large number of which are still owned by the army), which make them inaccessible. At Verdun, forts Douaumont and Vaux are open as tourist attractions, as is the original Vauban citadel and some of the lesser batteries; but that makes only a fraction of the 20 forts dotted around the area, not to mention many more that defend the right bank of the Meuse all the way down to St Mihiel, Toul and the Charmes Gap. A few other forts are open to the public elsewhere, such as Fort Pompelle near Reims; but the remaining majority must be approached in the spirit of one who enters a dense and trackless jungle of brambles in which man-made 30ft cliffs may open beneath one’s feet without warning at any time. Nor, indeed, is it unknown to encounter dangerous items of unexploded ordnance.

In the case of concrete pillboxes, probably the majority were either destroyed in the fighting or later demolished and removed from the landscape; but by their very nature the task of demolition is an onerous one, and far less straightforward for the landowner than simply ploughing over a trench. A large number of pillboxes may therefore still be found, incongruously lurking beside a farm midden or brooding over an empty field.

Sometimes their roof is flush with ground level, while in the case of Hussar Farm at Potije the concrete British observation post peeps out above a two-storied farm building. Thus a wide representative sample of the structures that were built may still be inspected, although very few have been made into tourist attractions. Most British tours to the Ypres salient seem to look at the German concrete machine-gun post on Hill 60, which was then ‘turned round’ for British use; although it may well be that Colonel Driant’s command post just behind the original French front line at Verdun (a particularly early example of a concrete fieldwork) attracts more visitors each year.

Original German block-built concrete shelters preserved in the German cemetery at Langemarck, Ypres. (Paddy Griffith)

When we come to the trenches themselves, which were surely the preponderant type of fortification in this war, we find that all too few have survived in any recognisable form, and still fewer have been consciously preserved. Nevertheless, some do remain as memorials, with concrete-filled sandbags to help them endure for the long term, for example, those of the Belgians at Stuivenkenskerke near Dixmude; of the Canadians at Vimy Ridge; and (with rock-walled rather than sandbagged trenches) of the French on the summit of Le Linge in the Vosges. There are others that have not been concreted but which are open to visitors, as at Newfoundland Park at Beaumont Hamel, Belleau Wood near Château Thierry or Navarin Farm east of Reims. Elsewhere there are a number of trench sites that have been partially maintained, although dark rumours persist that in some places new ones are still being dug to enhance their attraction to tourists! However that may be, it is very often possible to find the silted-up remains of genuine trenches in wooded areas away from the beaten track, where they have not been ploughed under the fields.2 Since 1918, for example, much of the Verdun battlefield was given back to nature, with the result that large sections of it are wooded today and very difficult to interpret, although with a little persistence one may still discern the trench lines snaking around beneath the undergrowth. Much the same applies to shell craters (although it is often difficult to decide just which holes in the ground in the middle of a wood were caused by HE bombardment, and which by the later uprooting of trees falling over in storms). When looking at shell craters it is always instructive to note their size and the distances between them. Thus at Newfoundland Park the craters caused by German fire in 1916 are relatively small and dispersed, whereas those at Vimy Ridge, caused by allied fire in 1917, are deep and overlapping. There is thus a clear difference between the two sites in terms of the intensity of the shelling that fell upon them.

Trenches in the museum at Sanctuary Wood, Ypres, in modern times. Although these fieldworks have been made neat and pretty for the tourist, they were probably not very much deeper or safer for the soldier in World War I than their present form would suggest. A man standing in them might not have had protection for his head. (Paddy Griffith)

4) Finally, if you wish to inspect deep dugouts or other subterranean works, there are few options open unless you are a professional archaeologist. In recent years great restrictions have been placed upon the excavation of such sites, and digs are usually organised only on an emergency basis, where there is subsidence or where new building projects threaten known works. The task of excavation is already difficult enough because the dugouts are by definition buried and by now often suffering from flooding or cave-ins; but it was made doubly so in the 1920s when many of the timbers, particularly those most accessible at the entrances, were plundered by local builders for use in the reconstruction. This often had the effect of collapsing the entrances and so hiding the location of the dugouts, which in turn rebounded on local people who later built houses on top of them, only to find a devastatingly high incidence of subsidence. The whole subject of subterranean works and their archaeological investigation, including mines as well as the evolution of deep dugouts, is authoritatively explained in the new book by Peter Barton and Peter Doyle.

Although the vast majority of sites are now inaccessible, there are nevertheless a very few subterranean works that may be inspected by the general public, such as the Caverne du Dragon near Craonne on the Chemin des Dames (which at one time in 1917 was an uneasy sanctuary for both sides at once!); the Arras city catacomb, and the mine tunnels under Vimy Ridge, the un-flooded levels of which are maintained by the Canadians. The Riqueval canal tunnel north of St Quentin may also be visited, but it has now reverted to its orginal purpose and shows few signs of its German occupation as a shellproof dormitory in September 1918.

Beaumont Hamel: Newfoundland Memorial Park is a section of the Somme battlefield essentially untouched since the Newfoundlers made their sacrifices there in 1916. It is on the road to Auchonvillers about 3km north-west of Hamel, which is 7.5km north of Albert by the D50 road (Department of the Somme). Monument et Parc Commémoratifs de Terre-Neuve, Rue de l’Eglise, 80300 Hamel, France.

La Caverne du Dragon at Hurtebise (4.5km up the D895 road west of Craonne, Department of the Aisne – some 22km south-east of Laon), is an enormous underground complex that has been greatly opened up to visitors in recent years. D18 ‘Chemin des Dames’, Oulches la Vallée Foulon, 02160 Beaurien, France.

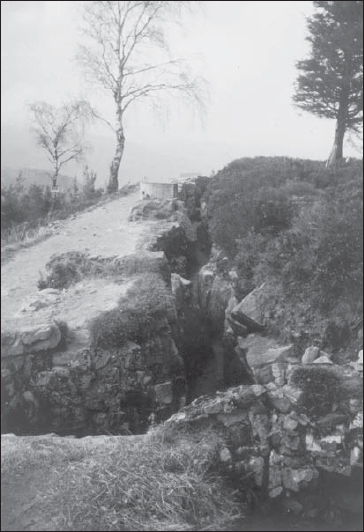

Reconstructed stone-built French trenches near the crest of the Hartmannswillerkopf in the Vosges, halfway between Munster and Thann. There was intense fighting here in January, April and October 1915, after which it became a ‘quiet’ front. Not shown are the concrete pillboxes which later added strength to the complex. (Dr Geoffrey Noon)

Le Linge: Scene of a fierce battle in 1915 on the summit of the Vosges. The preserved trenches are about 7km north up the D56 road from a point halfway between Stosswihr and Munster (17–22km west of Colmar), Department of Haut Rhin. Correspondence to Mémorial du Linge, BP 173, 68003 Colmar Cedex, France.

The Sommepuy (or Blanc Mont) American monument, 4.5km north-north-west of Sommepuy-Tahure just west of the the D77 road (about 40km east of Reims, Department of the Marne) is surrounded by original – but not artificially preserved – trenches, as is the Ferme de Navarin memorial, 3km south of Sommepuy-Tahure on the D77.

Stuivenkenskerke: The ‘Boyau du Mort’ (trench of death) is a concrete-preserved Belgian trench system overlooking the Yser river/canal about 2km north-north-west of Dixmude (23km north of Ypres, Flanders), including some original works. Yserdijkt 65, 8600 Diksmuide, Belgium.

Vimy Ridge: Approach the Canadian National Memorial either by driving north up the D55 from Neuville St Vaast (crossing the motorway), or by going west from the N17 at Vert Tilleul, 1km south of Vimy village or 10km north of Arras (Department of Pas de Calais). The memorial park includes a vast area of (not artificially preserved) trenches, shell holes and mine craters, as well as a neat group of trenches which are preserved with concrete-filled sandbags. Not only that, but there is also an extensive network of mine tunnels, including Grange tunnel which may sometimes be visited. Monument et Parc Commémoratifs du Canada, 62580 Vimy, France.

Verdun (Department of the Meuse): Fort Douaumont and Fort Vaux offer splendidly rewarding sites for the visitor, both above and below ground; as does Colonel Driant’s HQ bunker, and many more defensive works besides. Drive 4km up the D112 out of the north-east side of Verdun city then at the summit turn right onto the D913 for forts Souville, Tavannes and Vaux: then return to the crossroads and go straight ahead for a surfeit of monuments – but more importantly, Fort Douaumont. Go back west-north-west for 6km down the D913 to Bras: turn right 62km for Vacherauville, thence 6.5km north-west up the D905 to the Driant monument and battle HQ bunker. Further details from the Verdun tourist office, Place de la Nation, BP 232, 55106 Verdun, France.

Ypres area: Hill 60 and Sanctuary Wood, some 6km south-east of Ypres (Flanders), each boasts a private museum close beside some trench sites. Hill 60 is 1.5km south of Zillebecke, on a side road between Verbranden-Molen and Zwartleen (just east of the railway). Sanctuary Wood is up Maple Avenue, which is a cul de sac leading to the Canadian memorial on Hill 62. Find the entrance to the Avenue off the south side of the Menin Road at the foot of the slope about 0.5km west of the Hooge military museum. Further details of the Ypres area from the Visitor’s Centre of Ieper and the Westhoek, Lakenhallen (Cloth Hall), Grote Markt, 8900 Ieper, Belgium.

2 Using the same approach, many practise trenches of 1914–18 may still be discerned in military training areas where the land use has remained unchanged since 1914. Among others, the Aldershot area in England is dotted with such historic earthworks.