Aerial torpedo: a shell filled with Melinite (i.e. a French form of HE).

BEF: British Expeditionary Force.

Béton (French) or Beton (German): concrete.

Béton Armé (French): reinforced concrete (i.e. with steel rods incorporated in the structure)

Blockhouse: originally a strong building or sheltered part of a barracks. In 1914–18 it was used loosely for any dugout with shell-proof cover or especially any concrete structure.

Bunker: a living space with shell-proof overhead cover, often made of concrete.

Camouflaged trench: a trench covered by camouflaged canvas sheets to conceal it.

Communication trench (or ‘CT’): a trench built at 90 degrees to the front line through which men and supplies can pass from the logistic rear to the front-line trench.

Corduroy or Cord: treetrunks, telegraph poles, planks, fascines other timbers laid across a gravel- or hardcore-graded track to allow traffic to pass without bogging in.

CB: counter-battery (i.e. action designed to destroy enemy artillery).

Counter-scarp: a vertical (usually masonry) wall, sometimes up to 30ft high, on the enemy’s side of a fortress ditch: less vulnerable to fire than the ‘scarp’ which faced the enemy.

Deep dugout: as its name suggests, a British ‘Hangstellung’.

Duckboard: wooden decking or ‘board walk’ to allow troops to walk over wet or boggy ground (eg at the bottom of a trench) without sinking into it. In the rainy seasons at Ypres the only practicable paths across the battlefield were made with duckboards.

Dugout: an underground living space with shell-proof overhead cover.

Dummy (or ‘Chinese’) trench: a false trench created by the skill of the artist on a strip of canvas, to deceive enemy air photography. Used e.g. by 9th Division at Meteren, 1918.

Eingreif (German – literally ‘Intervention’): name given to German counter-attack divisions.

Fascine: a tightly bound bundle of brushwood or other sticks used to fill up a trench or pave a cord road, to allow trafficability. Cf the ‘fasces’ of ancient Rome had been symbols of state discipline, since the sticks had been used to beat malefactors (hence the modern word ‘fascist’).

Feste (German – literally ‘stronghold’): a wide locality carefully prepared for defence on the inner French border before 1914. They were essentially equivalent to fortresses but included several dispersed batteries rather than a single central ditched work.

Fort d’arrêt (French – literally ‘Stopping fort’, but perhaps better translated as ‘Spoiling fort’): an isolated outpost to plug one of the gaps planned in the Serré de Rivières system.

Flying sap: a trench dug in a single night, ie before the enemy knows where it is.

Fougasse: a hole full of stones or other shrapnel with an explosive charge beneath them, to be activated (by various means) when enemy troops are in the area. An early version of the modern claymore mine.

No. 106 Fuse: British fuse for an HE shell, intoduced in 1917, which detonated the shell immediately on contact with the earth, instead of after the shell had buried itself, as had been the case with earlier fuses. This allowed a wider lateral spread of the explosive effect, which was much more destructive not only to men, but eg to wire entanglements.

Gorge: the back wall of a fortress, facing away from the enemy.

Hangstellung (German): a deep shelter used as a dormitory, such as those built into the Lens (or east) side of Vimy ridge. The use of railway or canal tunnels for similar purposes was also commonplace wherever they could be found.

HE: high explosive.

Keep (or Redoubt): a set of fortifications entirely surrounded by a parapet, giving all-round defence. Normally located in depth behind a front line, but sometimes in the very front, e.g. ‘Manchester Hill’, which took the initial shock of the March offensive 1918.

MEBU (German: Mannschafts-Eisen-Beton-Unterstand) or Panzer-mebu: a reinforced concrete shelter for troops: normally a pillbox or other tactical blockhouse, but possibly also a ‘stollen’.

Mine: In traditional military parlance this was both a tunnel dug forward under the enemy’s defences (by ‘miners’) and the parcel of nastiness secreted at its far end, which in 1914–18 might consist of several tons of HE. Towards the end of World War I it also came to mean anti-tank devices attached to the pickets of a wire entanglement, which were contact detonated = the origin of the millions of contact mines deployed in World War II.

Parados: earth raised behind a trench to protect its occupants’ backs against shell fragments.

Parapet: earth raised in front of a trench for protection against both direct fire and shell fragments.

Pillbox: a bunker or blockhouse; the word was often used for a machine-gun post.

Revetment: strengthening of the walls of a trench, to stop it collapsing. It was done with sandbagging, brushwood mats or hurdles, often strengthened by wires, pegs and stakes.

Rideau défensif (French – literally ‘Defensive curtain’): a line of mutually supporting forts in the Serré de Rivières system, e.g. between Verdun and Toul.

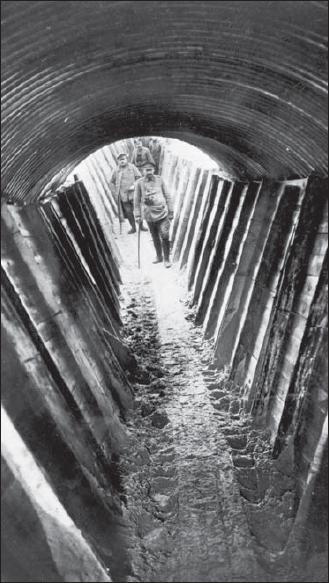

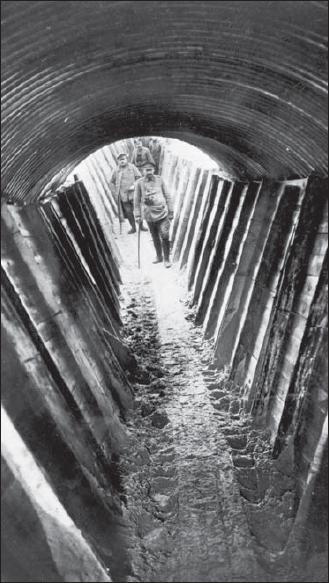

Russian sap: a 6ft 6in. sap dug towards the enemy some 2 to 3ft below ground level in timber frames (ie as a very shallow mine tunnel), allowing assault troops to advance at least part way across no man’s land without being seen. They featured in the assault plan for the first day of the Somme. The medieval tunnels beneath Arras were used as communication trenches in this way, whereas on Vimy Ridge the Canadians dug new ‘subways’.

Sangar (Hindi): Originally a circular parapet made of dry stone walling. In 1914–18 it came to mean any fortification dug upwards above ground rather than downwards into it, eg because of the high water table around Neuve Chapelle or Ypres.

Sap: A narrow trench dug by men (‘sappers’) working at the bottom and working sideways towards the enemy (in theory at a rate of 1ft 6in. to 3ft per hour, or 30ft per day), rather than starting on the surface and working downwards.

Scarp: the wall of a fortress ditch that faces the enemy, which he must climb. Cf the counter-scarp is the wall that faces away from him, which he must descend. In the fortress achitecture of 1871–1914 the scarp was often a gently sloping field, since any more sloping vertical wall would too easily have been destroyed by shell fire.

Shell scrape: the most minimal type of personal trench, rapidly dug only a few inches into the ground in the hope of enhancing protection against bullets or shell splinters.

Stellung (German): a position – either a single trench or a whole system of defence.

Stollen (German – literally a tunnel or gallery): used at Verdun for shelters close to the surface from which troops could launch an assault.

Trace: the ground plan of trenches or other fortifications, which might be marked out by tape on the ground, or even left as a 24in. deep ‘trace trench’ for later improvement.

Traverse: a buttress of earth between two adjacent sections of trench, to limit the effects of any shell burst or enfilade. Traverses gave the Western Front trenches their characteristic ‘cogged’ or ‘crenellated’ trace. The 1917 manual wanted each traverse to be 9–12ft long and extending at least 2ft in front of or behind the line of the original trench. Sections of trench between traverses should be 18–30ft long.

Trench-block: a makeshift obstacle that could be placed across a trench to prevent enemy raiders advancing along it. Typically a ‘knife rest’ made of a roll of barbed wire on a timber frame.

The kilometre-long tunnel built by the Royal Naval Corps in the dunes near Nieuport as a communication trench, or almost a ‘Russian sap’. (Imperial War Museum, Q 51039)