The last few spoonfuls of rice and green chicken curry warm my belly, but I still feel so strange and unsettled, like I’m dreaming. I set my plate down on the playa next to my camp chair, lean back, and take a long, slow gulp out of my mug of wine. I probably just need some sleep, but that can wait for now. A big night is about to begin.

I look around the circle at 60 to 70 Garage Mahal campmates, who are chatting or finishing their meals, and I’m struck by how bedraggled they look. I guess it isn’t so surprising. After all, I might have been driving all night and day through four states, but they’ve been partying at Burning Man since I left them five days ago.

“Well hey there, welcome back,” Bill says, grasping my shoulder warmly. “How was it?”

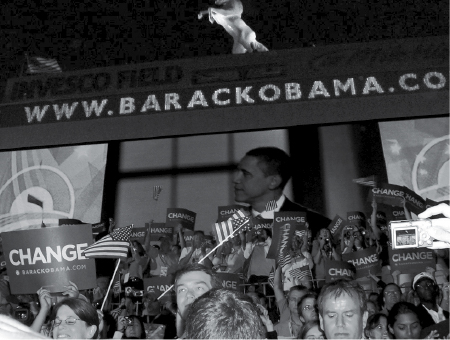

“Awesome,” I say, a little absently. “It’s still hard to believe that I watched Barack Obama accept the presidential nomination in Mile High Stadium last night, and now I’m here.”

“When did you get back?”

“Just a couple hours ago, maybe not even that. We left Denver around 2 a.m. and think we pulled into camp about 5:30 or so.”

“Whoa, quite a trip. Well, it’s good to have you back,” Bill says, patting my back and heading back toward his seat as Captain Ken calls the evening meeting together.

Ken and some of the other camp elders run through a few items of business — how great the art tour was earlier that day, the status of problems with the graywater pump on the showers, the importance of tonight’s art car volunteers spotting people and sand drifts for the driver — but I’m having a hard time paying attention.

I’m thinking about Barack Obama and the things he said and didn’t say, and about Sarah Palin, who was named as the GOP vice presidential nominee this morning, and the Guardian cover story on this whole saga that I just sent to my editor from the road, and the work that I will still need to do on it when I arrive at the hotel in Reno on Monday.

Fuck that, I tell myself, shake it off, Scribe. You’re at Burning Man. The work is done now and it’s time to have some fun in this big, beautiful city. “So let’s have a great night,” Ken concludes and Mahalers yip and howl as they rise and start hauling their chairs and dishes back to their tents and RVs to start getting ready. I’m still disoriented and don’t really know where I’m going, so I just survey the camp, trying to make it my home again.

The rough-hewn Shiva statue is ringed in fire and throwing off warmth. The dinner crew is washing dishes in the kitchen area. Rope lights and paper lanterns illuminate the pillows and fabrics in the covered chill area, momentarily tempting me to go lie down before I decide to plow through and get ready.

Digging into the bags in my trunk, I throw on the first costume I find and head into the camp area that Donnie, Heather, Rosie, and Kay are sharing, still in a daze. The place is abuzz with activity as we all dress and pull together the supplies for the evening. Heather applies some eyeliner to me at one point. The passing of time is only a vague concept.

“Rrrrrrroooooooowwwwwwwwrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr,” sounds the air horn on the art car, the first of many warnings that it’s almost time to go, sending the women into a more frenzied pace of preparation while Donnie and I fill everyone’s water bottles and bags and load a small ice chest with beer and other beverages.

It’s nice to have the car as a home base on nights like this, a place where we stash our stuff and the long fur coats that we’ll probably need later, once the chill of night sets in. We aren’t as mobile as we are on the nights when we decide to prowl the playa on our bikes, so forgetting your goggles or other key supplies can end up being a major regret.

Tick, tick, tick. “Rrrrrrroooooooowwwwwwwwrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr.”

“Okay, I’m going to stash our stuff on the car and grab a seat,” I tell Rosie or whoever is listening.

The car is fairly full, mostly with Garage Mahalers, but also some randoms that I don’t know as well. There’s already a couple nestled into the crow’s nest and our flame is burning a few feet above their heads. Below them, the top floor has 15-20 people standing around, and Jive is on the decks, playing some solid downtempo beats, giving me a nice surge of anticipation about the dance party out at Tantalus, way out in the deep playa, our main planned destination for the evening.

Ten minutes and three sirens later, Rosie, Heather, and the last of the Mahalers who have indicated an intention to join us arrive, the three spotters take their watchful positions around the car, and the “beep, beep, beep” of shifting into reverse indicates that we’re off.

Rosie grabs the seat I’ve saved next to me and we flip around to face out, leaning on the padded bar and letting my legs dangle off the edge. “So, here we are again,” I say to Rosie, starting to settle into playa life, as excitement begins to overtake my fatigue.

We just watch this wild world go by, the neighborhood street ending at the open playa, intricate patterns of fire and blinking lights filling the horizon in front of us, creative creatures floating past us on foot or bicycles, art cars ranging from a small neon head to massive whale sailing along at our same 5 mph pace, all making wide arcs around the deep drifts of sand that are the worst I’ve even seen, catching bicycles like beartraps.

As we look out, outsiders look in, passersby dancing to the bass-heavy breakbeats that we’re now cranking at full volume, drawing some passersby to board us in the back as we chug along, some stepping into our lower area, some climbing the ladder to the top.

We pass Big Rig Jig, two semi-tractor-trailers dancing up into air like a double helix. We pass the Man, then the Temple, and continue on into the dark, deep playa, the horizon now far less intense, dotted sporadically with lights of fellow burners. Far in front of me, I can make out Opulent Temple and barely hear its beats even though we’re maybe a mile away, but the cacophonous sonic landscape has begun to simplify around the Garage Mahal sound, our music and voices.

And then we stop, and Ken sounds the siren, indicating that we’ve arrived. But where? The playa in front of me is vast and black on this moonless night as everyone pours out of the art car, and then, as I flip my legs back around to get out, I see where we are and remember: the red, white, and blue spinning top hat, the strobe light flashing through the darkness, putting Tantalus into motion, a naked man emerging from the muck and mire, reaching for the golden apple that is just beyond his grasp, falling back in defeat, over and over again.

This is where my long odyssey began, out here last weekend, chatting with artist Peter Hudson as he and his crew built what I considered the best artwork on the American Dream theme. It was a compelling metaphor that I pondered on my drive to Denver, wondering whether I’d find something like a Golden Apple in my journalistic exploration.

Did I? Right now, my mind a mix of road numbness and sensory overload, I’m really not sure. It’s all such a jumble of heady experiences that I captured in a half-dozen long blog posts and a 5,000-word cover story. But I try to just shake it off and be here now, heading toward Tantulus, hoping to find Hudzo.

Reaching for the Golden Apple

How would the American Dream theme shape Black Rock City during this huge political moment in time? Was Burning Man going to somehow manifest the “hope and change” that Barack Obama was promising a war-weary nation? Were there others like me who wanted to explore the road between this isolated counterculture and a dominant political culture that was seeking new blood and energy?

Those are some of the questions that I pondered as I explored the still-forming Black Rock City for a couple days before I was to set off for the Democratic National Convention. Initially, it was hard to spot any discernible difference in life on the playa in 2008, although there may have been a bit more political provocation than normal or than there had been four years earlier, during that last pivotal presidential election.

Around Center Camp, there were some guerrilla posting of messages urging personal action in fighting the power and saving the planet. And the usual series of signs that greet visitors driving in featured pointed quotes by thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson, William T. Sherman, and Alexis de Tocqueville (but not a single quote by a woman).

But most of the political statements out there were in the artwork, like Bummer, a massive wooden Hummer replica slated to burn, or Tantalus, the only piece that really seemed to resonate with this particular American moment and my exploration of how this counterculture saw the national political culture.

The ancient Greek story of Tantalus was of someone who stole ambrosia and nectar from the gods to share with his people, and for that and other mistakes he was punished for eternity by having the water at his feet and fruit over his head pulled back whenever he reached for them.

Artist Peter Hudson, famous for using stroboscopic lighting to simulate the movement of his sculptures (include the swimmers of Sisyphish and swinging monkeys of Homouroboros), reimagined the legend as a man reaching for a golden apple that was being pulled out of his reach.

Visitors would help power the movement by working the pumps of what looked like on rail cards, but when I saw the static piece on that Sunday morning in the deep playa, it looked like a giant red, white, and blue top hat, the kind I anticipated seeing at the Democratic National Convention, where performance artist Kid Beyond and I would be headed that afternoon.

Tantalus seemed like a telling metaphor for such a big week in American politics, and I was curious how Barack Obama and the other Democratic Party speakers would try to define that Golden Apple and who’s keeping it out of reach, and to perhaps explain how they’ll help the average American reach it.

The news that Obama had just selected Joe Biden as his running mate slowly trickled out to the playa with the new arrivals, but nobody there really cared much. Everyone was too busy setting up or getting adjusted, and when we did talk politics during rest breaks, Biden seemed to everyone an understandable if boring choice.

There were plenty of political junkies out there, including two friends who let me crash in their RV for the last two nights and who were both headed to Denver in the coming days. Democratic Party consultant Donnie Fowler would be staffing Al Gore, and his sweetie, Heather Stephenson, founded the green tip website Ideal Bite and was headed out Monday to appear on a panel on alternative energy with the mayors of San Francisco and Colorado.

“The American Dream to me is not having barriers to achievement,” Heather told me when I asked. It is Tantalus getting some apple if he really reaches for it. Donnie said it’s, “the freedom to pursue your own dream without interference by government or social interests.”

Burning Man was certainly about pursuing dreams and pushing past barriers, but the conversations didn’t really illuminate much for me. Besides, Donnie and Heather worked in politics and came to Burning Man for their vacation, so they didn’t seem to really be burner ambassadors interested in bringing this culture into the halls of power.

So I kept looking and asking around and eventually found what I was looking for: The Philadelphia Experiment. Most of their members were busy building a theme camp and performance stages at the corner of Esplanade and 8 o’clock in Black Rock City. But four of their key members would soon be taking a little side trip to the Democratic National Convention.

They were part of the Archedream dance troupe and would be joined in Denver by three other members from their native Philly that couldn’t make it out to the playa this year. Burning Man figured prominently into how this highly political performance came together and with the message they were trying to spread.

It was on the playa that the Philly crew linked up with Bay Area artist Eric Oberthaler, who used to choreograph San Francisco artist Pepe Ozan’s fire operas on the playa, and the collaboration resulted in “Archedream for Humanity,” which went on a national tour after premiering Tuesday at the Democratic National Convention.

To three of the young and idealistic artists behind the show — who I interviewed during a dust storm on the playa on the Sunday that I left for Denver — the connection between these two big events is important. And they say the artistic and collaborative forces that Burning Man is unleashing could play in big roll in creating a transformative political shift in America.

“These are two amazing events that are kind of shaping the world right now,” Archedream director Glenn Weikert said of Burning Man and Obama’s acceptance of the Democratic Party nomination for president. “A lot of the ideas and views are similar, but people are working in different realms.”

As we spoke, a Black Rock Ranger came over to tell us that a cold front was coming in and “it’s going to get windier and colder,” making me feel a bit better about my impending departure. Greg Lucas said his main reason for getting involved in the performance was to try to somehow make a difference: “I wanted to do something that would have a social and political impact.”

The country under President George W. Bush had gone astray, and they wanted to be a part of the correction. Their three-act performance shows the past, present, and future of American life. “Act One ends with the loss of hope,” Weikert said. Then the audience overhears a modern dinner table conversion, with people just trying to get by in this hyper-consumerist culture. And the future they envision is one of liberation, awakening, “and the concept of the choice that we have going into our future,” Weikert said.

Such messages often aren’t well understood by the average American, who has been too scared, selfish, and busy to really step back and contemplate what was happening in the country. They said Burning Man offers a chance to just slow down, think, and reflect, away from the daily rat race.

“Burning Man is a great town for that,” Bill Roberts, one of the performers, told me. “It’s about engaging with your community and trying to turn off that crazy business.”

Yeah, turning off that crazy business and creating an intentional community, although the ridiculously long drive into the heart of mainstream modern politics that we were about to take could certainly qualify as crazy business. But to these guys, one’s intention determined the value of the act.

“Just us deciding to spend our labor and capital making a statement is a political act in its own right,” Roberts said, and he was right, although I still wondered about how effective it could be. Weikert said they were like burner ambassadors: “Maybe the Burning Man community is trying to reach out.

Traveling Between Dreams

Kid Beyond and I left the playa around 3 p.m., just as the dusty winds were beginning to howl, starting the 16-hour drive from Black Rock City, cruising through Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado, states which Barack Obama would need to win at least a couple of in November if he was to take the White House.

There is a certain romance to the road trip, and I imagined the insights that would come to me with so much time to ponder my quest. But it was mostly just a mind-numbing trek punctuated by the minor stresses of trying to stay awake and almost running out of gas as we neared the Utah border, which would have been a major complication to our trip. We needed to pick up our Democratic National Convention press credentials by noon on Monday or they would be reassigned to other journalists.

Kid, aka Andrew Chaikin, wasn’t a journalist. He was a beatboxing musician who also did voice-over work (his was the voice of Sprint Communications at the time), designed games, and did consulting work naming companies and products. But it was his roles as a burner and political progressive that brought him on my trip and earned him one of the Guardian’s two press passes.

In figuring out the logistics for the trip, I knew that I couldn’t do it alone, but having the Guardian pay an accomplice was financially prohibitive. Then, at a party in San Francisco, I mentioned it to Kid and his immediate reaction was, “I’m going with you,” a stance he never wavered from. He was a welcome addition whose help and insights I still appreciate.

“Monday morning. Just finished the 18-hour drive from Black Rock to Denver — Steve and I switching shifts throughout the night, fueled by Radiohead, live Floyd, Rage Against the Machine and drive-thru Burger King,” Kid wrote in his first blog post for the Guardian. “I’m aching to augment my 2.5 hours of sleep, but there’s only enough time to wash the playa dust out of most of my crevices and head downtown to the Circus. And a circus it is: part rock concert, part revival meeting, part infomercial, part telethon.”

We headed south toward Denver just as a gorgeous dawn was breaking, arriving with a few hours to spare before our Democratic National Convention press credential would have been reclaimed by other journalists, who reportedly numbered more than 15,000 here. But we were the only ones with silly burner bicycles on the back of an overloaded, dust-covered rental car.

The convention kicked off that night with Michelle Obama, Nancy Pelosi, and Ted Kennedy, among others. But after picking up our credentials at the Sheraton and starting to switch roles and get myself engaged with covering a very different kind of spectacle, we mostly just needed a nap.

That evening, the massive Pepsi Center was less than half full a couple hours after the gavel fell to open the Democratic National Convention, but the city of Denver was bustling and eventually so was the hall. I rode my burner bike along the beautiful and efficient Cherry Creek Bike Trail to get there and it was a smart move because most of the streets around the convention are closed off and patrolled by police in riot gear riding trucks with extended running boards, with military helicopters circling overhead.

Many of the delegates and other attendees that I talked to said it took them a long time to get from their hotels into the hall. Even riding a bike here involved a long walk because of the huge perimeter they’ve set up around the hall. But the broadcast media had it good, with prime floor space that made it all the more congested for the delegates and others with floor passes. Most journalists were tucked behind the stage or up in the cheap seats.

CNN also has a great looking patio restaurant set up across from the entrance advertising, “CNN Bar: Burgers, Beer, Politics.” But by the “must have credentials” sign on the door, they actually meant CNN personnel only, not their media colleagues in general. Jesus, how many of them could there be?

The convention was mostly a big infomercial for the Democratic Party and a way to rally the faithful, but I set out to do some reporting on the San Francisco delegation, catching up with Hillary Clinton supporters Laura Spanjian, Mirian Saez, and Clay Doherty.

Despite the fact that Clinton announced that she was releasing her delegates to vote for Obama, they were still planning to vote for Clinton on Wednesday, although all said they would enthusiastically support Obama thereafter.

“It’s important for me to respect all the people who voted for her and to honor the historic nature of her candidacy,” Spanjian said. “And most of all, to respect her.”

“This morning, Hillary showed up at the Latino caucus and gave a great speech,” Saez said. “She said it’s not about her or about him, it’s about taking back the country.”

“It’s about the Republicans and we can beat them this time,” added Spanjian.

We. They. It seemed so binary, despite how I shared their desire to see Obama in the White House. In many ways, the convention had about as much to do with achieving real change — the kind of bottom-up, grassroots transformation that the country needed — as Burning Man did.

Saez was serving as a delegate for her third presidential convention in a row. I asked her what value she saw in conventions like this, which seem to be mostly about preaching to the choir. Yet she said the string of speakers at the podium are valuable in reaching undecided voters and changing the political language.

“One of those people are going to resonate with someone who’s undecided,” Saez said. “And for us here, we gain energy so we can get the job done in November.”

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi tried to rally the faithful for the “historic choice between two paths for our country.” The emotional highlight of the evening was the speech by Ted Kennedy, who was battling brain cancer and was reportedly not certain if he was going to speak.

“Barack Obama will close the book on the old politics of race and gender and group against group and straights against gays,” Kennedy said, adding, “This November, the torch will be passed again to a new generation of Americans.”

Inside the Big Tent

The real action seemed to be in the streets outside the hall, where divided America was on display. There were anti-war protests that sought to “Recreate ‘68,” referring to the disastrous protests outside the 1968 convention in Chicago, which helped elect Richard Nixon and set the country on a more conservative course.

The right-wing culture warriors were on the streets in a smattering of protests, flying their flags and displaying their signs, the most disturbing being a half-dozen anti-abortion activists bearing signs that read, “God hates Obama,” “God is your enemy,” “The Siege is Here,” and one, wielded by a boy who was maybe 12 years old, reading, “God hates fags.”

Jesus, who would want to worship such a hateful supreme being? For all the hope that Obama seemed to be ushering in, it was already becoming quite clear what kind of right-wing backlash this uppity black lawyer with the funny name would provoke. But there were also positive signs of life from grassroots America there as well, the same kind of people I could imagine meeting in Black Rock City.

The Big Tent, which was the central hub for bloggers and progressive activists there in Denver, offered free beer, food, massages, smoothies, and Internet access — almost like a theme camp, organized with the same online tools that were essential to the rise and longevity of Burning Man. But the Big Tent offered something even more crucial during this big political year: the amplified voice of grassroots democracy, something finding an audience not just with millions of citizens on the Internet, but among Democratic Party leaders.

New media powerhouses including Daily Kos, Move On, and Digg (a Guardian tenant in San Francisco that sponsored the main stage in the Big Tent) had spent the last year working on the Big Tent project with progressive groups in Denver, many of whom have offices in the Alliance Building, the parking lot of which houses the Big Tent, which was built with a simple wood-framed floor, stairs, and decks above it, covered by a tent.

“This is where we have the people on the ground doing the work on progressive causes,” said Katie Fleming with Colorado Common Cause, one Alliance Building tenant. “It’s been a year in the planning. The idea was having a place for bloggers to cover the convention…It’s a way for us to all come together for the progressive line that we carry.”

But it was really more than that. It was a coming together of disparate, ground-level forces of the left into something like an real institution, something with the power to potentially influence the positions and political dialogue of the Democratic Party — a feat that would be the first necessary step toward real change.

“When we started doing this in 2001, there just wasn’t this kind of movement,” Move On founder Eli Pariser told me as we rode down the Alliance Building elevator together. “The left wing conspiracy is finally vast.”

Pariser said that political conventions aren’t really his thing, but that “it’s an interesting anthropological phenomenon.” Indeed it was, and I immediately spotted many similarities to Burning Man. Both were part-party, part-movement; collections of basically like-minded people with myriad agendas and only a vague sense of common purpose. And both had an inertia to them that made change or reform difficult. They simply were what they were, try as we writers and talkers might to inject them with special meaning and significance.

On the Tuesday I was there, populist pundit Arianna Huffington was among the notable visitors to the Big Tent, speaking from the Digg Stage about the obligations and failing of today’s journalists. “Our highest responsibility is to the truth,” said the founder of the widely read Huffington Post blogger hub. “The truth is not about splitting the difference between one side and the other. Sometimes one side is speaking the truth…The central mission of journalism is the search for truth.”

Parties and the Party

Political conventions are scripted affairs, right down to the actual vote that selects the nominee, which is ostensibly the reason for the convention and the only real democratic business to take care of.

“This is the best part of the convention, roll call. It’s cool,” San Francisco Supervisor Chris Daly, a convention delegate and serious political junkie, told me as I joined him on the convention floor during the nominating speeches and roll call vote. “The speeches are okay, but this is what it’s about.”

Daly was an early Obama supporter who was anxious to see the party finally dispose of Hillary Clinton and rally around his guy. After the previous night’s Clinton speech and the ongoing statements of support for her by many delegates, the room was starting to show its most enthusiastic support for Obama yet. “It feels like it’s just switched from being Hillary Clinton’s convention to Barack Obama’s convention,” Daly said. “We’re getting close to unity.”

Each state reported out their vote totals for each of the candidates, but when it came California’s turn, state party chair Art Torres said, “California passes.”

“What!?!?” exclaimed many delegates, and there was bedlam among the delegation. What the hell was going on? Immediately, Daly and others speculated that Hillary had gotten too many votes and the state party was passing in the name of party unity. “It’s probably because of Hillary,” Daly said.

Ultimately, it seemed that Daly was right, but not exactly in the way he meant it. Other states also passed as Obama neared the total votes he needed to be nominated, and then New Mexico yielded to Illinois (Obama’s home state), which then yielded to Hillary Clinton’s home state of New York. Video screens showed Clinton entering the hall and joining the New York delegation. “In the spirit of unity and with the goal of victory,” Clinton said, “let us declare right now that Barack Obama is our candidate.”

It was a big, dramatic moment and the partisans ate it up as the band broke out “Love Train” and everyone danced and cheered. This was the business of politics in America, and it did have a certain dreamlike quality, a surreal veneer to such a serious realm. And at the end of these days, it was all about who could get into the best nighttime parties.

San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom threw one of the hippest parties of the week, a shameless salute to the “Obama Generation” by a politician who had enthusiastically backed Hillary Clinton. Even though he didn’t get a speaking slot at the convention, Newsom was widely seen as a rising star in the party, far cooler than most elected officials, maybe even too cool for his own good.

Comedian Sarah Silverman did a funny bit to open the program at the Manifest Hope Gallery (which featured a variety of artworks featuring Obama), then introduced Newsom by saying, “I’m honored to introduce a great public servant and a man I would like to discipline sexually, Gavin Newsom.”

Apparently Newsom liked it because he grabbed Silverman and started to grope and nuzzle into her like they were making out, then acted surprised to see the crowd there and took the microphone. It was a strange and uncomfortable moment for those who know about his past sex scandal and recent marriage to actress/heiress Jennifer Siebel, who watched the spectacle from the wings.

But it clearly shows that Newsom was his own biggest fan, someone who thinks he’s adorable and can do no wrong, which is a dangerous mindset in politics. When his campaign for governor of California the following year went nowhere, I think only Newsom was surprised, although he did go on to be elected lieutenant governor in the 2010 election.

After letting go of Silverman, Newsom took the microphone and thanked the event’s corporate sponsors, from PG&E (a horribly corrupting influence in San Francisco politics) to AT&T (facilitators of Bush Administration warrantless wiretapping). “Thanks to everyone who made this happen,” Newsom said. “We appreciate their largesse.”

Newsom urged attendees to aggressively campaign for Obama, telling them, “It is one thing to talk about hope, but it’s another thing to manifest it.”

I was already getting that impression. After supporting Obama’s call for a new kind of politics all year, it was hard to see how this party and this political system was going to allow him to manifest it in the doses and with the substance that the country needed. But I still felt hope as we prepared to hear from The Man.

Man in the Middle

Barack Obama finally took center stage as the Democratic National Convention drew to an explosive close in a packed Mile High Stadium. Most on hand thought he gave a great speech and left smiling and enthused when it was over, but I and some other progressives had a few cringing moments that left us slightly unsettled — and previewed the disappointments that we would feel during the first year of his presidency.

While Obama and the Democrats made a clear and compelling case for how much better for the country they are than John McCain and the Republicans, there were also many points of concern for progressives and the alienated Left — not to mention the relatively apolitical citizens that were partying in Black Rock City at the time.

Obama played hard to the center of the political spectrum, talking about “safe” nuclear energy, tapping more natural gas reserves, and ending the Iraq War “responsibly.” He stayed away from anything that might sound too liberal, while reaching out to Republicans, churchgoers, and conservatives with reassurances that the “change” he was pushing was more rhetorical than radical.

But he also made a statement that should — if we are to truly restore hope and democracy in this tattered country — shape American politics in the coming years: “All across America something is stirring. What the naysayers don’t understand is this isn’t about me — it’s about you.”

Well, if this is really about me and the people I spend time with — those of us in the streets protesting war and the two-party system, people at Burning Man creating art and community — then it appeared that electing Obama is just the beginning of the work we need to do. If we were going to trade guns for butter, or armories for art, it was going to come from the people, not a president promising to escalate the war in Afghanistan.

During one of the most high-profile points in the convention, halfway between the Gore and Obama speeches, a long line of military leaders (including one-time presidential candidate General Wesley Clark, who got the biggest cheers but didn’t speak) showed up to support Obama’s candidacy. They were followed by so-called average folk, heartland citizens — including two Republicans now backing Obama. One of the guys had a great line: “We need a president who puts Barney Smith before Smith Barney,” said Barney Smith. “The heartland needs change, and with Barack Obama we’re going to get it.”

Yet I’m a progressive whose big issues (from ending capital punishment and the war on drugs to transitioning from the Age of Oil to creating a socialized medical system and more justly distributing the nation’s wealth) have been largely ignored by the Democratic Party. I understand that I wasn’t Obama’s target audience in trying to win this election, but I was hoping that Obama would begin to educate Americans as he led us in a more responsible direction. And that he would offer some reason for the burners in Black Rock City to begin to see value in involvement with the political system.

So I was a little disappointed, despite appreciating this heady moment. After all, this was certainly a historic occasion. Bernice King, whose father, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech 45 years to the day before Obama’s acceptance speech, echoed her father by triumphantly announcing, “Tonight, freedom rings.” She said the selection of Obama as the nominee was “decided not by the color of his skin, but by the content of his character. This is one of our nation’s defining moments.”

But there is still much work to do in convincing Obama to push a progressive vision once he’s elected. “America needs more than just a great president to realize my father’s dream,” said Martin Luther King III, the second King child to speak the final night of the convention. Or as Congressman John Lewis, who was with King during that historic speech, said in his remarks, “Democracy is not a state, but a series of actions.”

Yes, there is no end point at which democracy is attained — or when a new, more effective and inclusive culture is created. Both are processes that require lots of time and work. During this 5,000 mile, 10-day trip, starting and ending at Black Rock City in the Nevada desert with Denver and the convention in between, I was coming to see Obama as what I took to calling the Man in the Middle.

That creature is essential to both Burning Man and the Democratic National Convention, a figure of great significance — but also great insignificance. Ultimately, both events are about the movements that surround and define the man. It was up to us to participate in those movements in ways that inform and shape them.

And even then, despite my fervent hopes for both Obama and Burning Man, I was having doubts that either entity was capable of facilitating the kind of big fundamental changes that I felt the country desperately needed on so many fronts after being so badly damaged by eight years of President George W. Bush and the post 9/11 mania he encouraged.

The county had become so myopic, fearful, and divided, so utterly dysfunctional in its ability to deal with its problems in ways that didn’t rob from future generations. I had lost so much faith in the modern political and economic systems, yet Obama and Burning Man seemed to be the antidotes, offering fresh perspectives and inspiring messages. Surely, they had the potential to help us correct our course, right?

Every year, my visit to Burning Man restored my faith in humanity and its infinite creativity and goodwill. It is such a beautiful and inspiring place, Black Rock City, shining out from the dark desert like a harbinger of human possibility. As I rode my silly, furry, whimsical burner bike away from Mile High Stadium, on a freeway closed down for security reasons, I thought about the playa and how anxious I was to get back.

Back to the Burn

Kid Beyond, Donnie Fowler, and I left Denver around 1:30 a.m. Friday, a few hours after Obama’s speech and the parties that followed, driving through the night and listening first to media reports on Obama’s speech, then to discussions about McCain’s selection of Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his running mate.

The Obama clips we listened to on the radio sounded forceful and resolute, directly answering in strong terms the main criticisms levied at him. Donnie said the Republicans made a very smart move by choosing a woman, but he was already getting the Democrats’ talking points by cell phone, most of which hammered her inexperience, a tactic that could serve to negate that same criticism of Obama.

We arrived back on the playa at 5:30 p.m. Friday, and when a Burning Man Information Radio announcer said the official population count was 48,000 people, the largest number ever to date, I thought about what Larry Harvey had told me earlier that year: “That city is connecting to itself faster that anyone knows. And if they can do that, they can connect to the world. That’s why for three years, I’ve done these sociopolitical themes, so they know they can apply it. Because if it’s just a vacation, well, we’ve been on vacation long enough.”

Yet when I toured the fully built city, I saw few signs that this political awakening was happening. There weren’t even that many good manifestations of the American Dream theme, except for Tantalus, Bummer (a large wooden Hummer that burned on Saturday night), Altered State, an artsy version of the Capitol Dome by artist Kate Raudenbush, and Opulent Temple interrupting the Saturday night dance party to play some of Obama’s acceptance speech.

Most of the people who attend Burning Man seem to have basically progressive values, although many have a strong libertarian bent, and some of them are involved in politics. But the event is their vacation. It’s a big party, an escape from reality. It’s not a movement, at least not yet, and it’s not even about that Black Rock City effigy, the Man. But I could feel Burning Man’s impact on the culture, feel it building toward…something.

But it certainly wasn’t about the Man, whatever that symbolized to people. Hell, in 2008, many of my friends who are longtime burners left on Saturday before they burned the Man, something most veterans consider an anticlimax. After a long fun party day on Saturday, my first full day of Burning Man that year, Rosie and I slept through the burn, got up in the middle of the night, costumed up, and roamed the playa through dawn and into the next day.

So, ultimately, it isn’t really about the Man in the Middle; it’s about the community around it and how that community was being shaped by its involvement with Burning Man. And if the community around Obama wants to expand into a comfortable electoral majority — let alone a movement that can transform this troubled country — it was going to have to reach the citizens of Black Rock City and outsiders of all stripes, and convince them of the relevance of what happened in Denver and what’s happening in Washington, DC.

Larry Harvey can’t deliver burners to the Democratic Party, or even chide them toward any kind of political action. But the burners and the bloggers are out there, from Archedream for Humanity to the Big Tent, were ready to engage — if they can be made to want to navigate the roads between their worlds and the seemingly insular, ineffective, immovable, platitude-heavy world of mainstream politics.

“As hard as it will be, the change we need is coming,” Obama said during his speech.

Maybe. But for those who envision a new kind of world, one marked by the cooperation, freedom, and creativity that are at the heart of this experimental city in the desert, there’s a lot of work to be done. And that starts with individual efforts at outreach, like the task undertaken by the guy standing alone in the heat and dust, passing out flyers to those leaving Black Rock City as Burning Man ended on Monday.

“Nevada Needs You!!!” began the small flyer. “In 2004, Nevada was going Blue until the 90 percent Republican northern counties of Elko and Humboldt tilted the state. You fabulous Burners time-share in our state for one week per year. This year, when you go home please don’t leave Nevada Progressives behind! ANY donation to our County Democratic Committee goes a long way; local media is cheap! Thanks!!!”

Change comes not from four days of political speeches or a weeklong party in an experimental city in the desert, but from the hard work of individuals with the vision, energy, and tribal support to help others see that vision. To realize a progressive agenda for this conservative country was going to take more than just dreaming.

The Party’s Over

I returned from the desert with these grand political notions swirling in my head, but neither Barack Obama nor Larry Harvey had the answers that I was looking for or the perspective that I needed. The men in the middle of these movements didn’t seem to really be leading them. At best, they were figureheads.

Sure, I wanted to believe in Obama’s hope and change after a dismal eight years of Bush. And I wanted to believe that Larry could steer Burning Man toward the sociopolitical relevance that he was seeking. But I didn’t believe that either of them were actually capable of leading the way, particularly given the disparate band of outsiders in their respective realms.

The people I knew who voted for Obama, and those who attended Burning Man, just weren’t followers. They were leaders, millions of them, people who had been resisting the country’s leaders for so long that they were probably incapable of following anyone anymore. And now, they didn’t need to. This was their time to shape their worlds.

So that’s who I turned to for my perspective and inspiration, my contemporaries, those once deemed the slackers of Generation X who had discovered something about the world and themselves out in the desert, something that shaped who they chose to be. I talked to Tom Price and Carmen Mauk, who worked different ends of the Burners Without Borders movement, and Rebecca Anders, my Flaming Lotus Girls mentor, who was moving on to bigger things within the larger Burning Man world.

“The opportunity for you to see yourself in this great creativity is the gift that everyone is offering to you,” Carmen told me. “Burning Man, as an organization, is really becoming a curator of this community’s activities, projects, successes, culture, and as an event production company. We are now in a position to be about to broadcast this and help people grow these things in a way that we never have before.”

Burning Man is really more of a cauldron than a movement, a place where people learn about themselves and others. Here’s how Tom put it: “I’ve said for years that if you go to Burning Man and pay attention, you will learn who and what you are. You will learn whether you’re generous, whether you plan ahead, whether you’re thoughtful, whether you’re open-minded, whether you’re selfish — you will learn exactly who you are because there’s nowhere to hide in that big emptiness. All you have is who you are, for better or worse, and that kind of openness allows you to get real with people.”

The burners who stick with it and are influenced by it are these people, the ones who find themselves on the playa and like what they see. It is the thousands of people having those kinds of simultaneous epiphanies that binds the culture together more than any art themes or statements of principles. People intuitively know they are creating a new kind of community on this blank canvas. And that’s why Tom agreed with me that the 2004 presidential election helped trigger the Burning Man renaissance.

“I think the natural organic evolution happened to coincide with that. And also, a culture that was based primarily on survival for a long time, both a physical survival, a critical mass of people learning how to survive in the desert, once you’ve created that, then they can create the nuanced and rich and deep culture and the many permutations of it, the subcultures within the culture, that has happened within the last few years at Burning Man. And that needs to continue to grow and evolve or it becomes stuck, it become static, it implodes under its own weight. Since creativity is the engine that drives it, once it stops being creative, the motivation to participate becomes diminished and you get a city full of tourists coming to experience a thing that has already stopped happening,” he said.

But that isn’t what happened to Burning Man. Instead, the culture blossomed in ways that surprised even hardened cynics. Rebecca became reinspired by that creativity by 2009, losing her earlier cynicism as she watched the culture mature and extend its shoots in all directions.

“I think it’s sort of understood as something that has potential paths to greater thought or wisdom or deep inspiration because crazy things happen out there and people come back from it changed and they go, ‘Wow, I never considered this and that,’” Rebecca said. “It’s part of people’s cultural identification. It’s a mark of pride for a lot of people that they went to Burning Man and got something out of it. And there’s still a lot of misconception about Burning Man by mainstream culture.”

Rather than the bacchanalian freakfest it was once purported to be, and how Rebecca remembers it from those early years, “Burning Man is becoming way more mainstream,” she said, uttering a label that might make some burners cringe. “The fire is gone out of the belly of Burning Man. It is not the wild, untamed beast that it once was. It just isn’t, and that’s okay. That’s the way it fucking goes,” Rebecca said.

“But the overall cultural impact of even the most short-term, superficial, party kind of experience at Burning Man has some really, really potent effects, even if they’re like low-level effects, in people’s lives regarding their tolerance and their openness and their ability to accept something weird that’s being done in the name of information or art or whatever,” she said. “So I’m noticing a lot more of the lower level effects fanning out into society, and I’m finding that to be a really positive and productive thing.”

Rebecca, Tom, and Carmen have seen it happen all over the world, from corners of San Francisco to the regional events around the country. Rebecca said it’s gotten to the point where people don’t even need to go to Burning Man anymore, particularly once it has infected them.

“They’re opening up their minds and making metal shops in their garage and learning how to papier-mache and thinking up new weird things, without going too far out of their area, which is critical for this country. We need those people to stay home and be creative. Yeah, they can go away, but they gotta come back. The Midwest needs them. I’m from there, I know,” Rebecca said.

Carmen and Tom both agree, saying that it isn’t the party, lights, and music — or even the art — that had come to define Burning Man. It was its spirit, its ethos, that certain burner something.

“People are starting to say that’s the celebration event, not who we are. People are starting to define themselves around these community events they’re creating, and those are starting to become the culture of Burning Man,” Carmen said. “Burning Man is starting to be more in its proper place, as an event.”

But the culture that event spawned, in its multitude of forms, in pockets all over the world, orbiting around Black Rock City, that’s what has motivated this trio to stay so involved with Burning Man.

“Even if it ends this year, the fact that it had a 22-year run as a counterculture is extraordinary. I can’t think of anything else that comes anywhere close,” Tom said in late 2008. “I think it is so durable because they have resisted attempts to force meaning on it.”

The Burning Man culture had become quite durable, partly because of key burners that were ensuring the event and its artists had spaces where they could flourish.

Big Art Studios is Born

The story of Burning Man art has an arch that runs roughly from Baker Beach in San Francisco to the massive American Steel workspace in West Oakland, which was renamed Big Art Studios when longtime burner artists Karen Cusolito and Dan Das Mann signed the lease on the entire building on April 1, 2009.

The eight-foot wooden Man that Larry Harvey built and burned in 1986 presaged the oversized steel artworks that would follow in its wake over the coming decades, the tinkering of individual DIY hobbyists supplemented by ambitious teams of countercultural artists seeking something more than just an annual showcase for their work.

They wanted to make art full-time, collaborating with a huge community of creative strivers, and to transform their culture into something permanent and sustainable. And to do so, they founded gigantic workspaces in the East Bay Area, including The Shipyard, Xian, and NIMBY Warehouse.

But the biggest and most technologically advanced was American Steel, a relic of a bygone industrial era that was slated to be converted into a huge condominium complex when it was intercepted by a confluence of a sagging national economy and rising demand from Burning Man artists.

“Between 2004 and now, many of us have found a way to make a life of what we did in the counterculture that became Burning Man,” Dan told me, emphasizing that it was the countercultural artists of the Bay Area that created Burning Man, not Larry Harvey or the organization he created. “We put Burning Man on. The LLC doesn’t put it on. All they brought are a fence and some porta-potties.”

Dan can be a little harsh when it comes to discussing the Borg, and he admits that his relationship with them has been strained at times. He gives John Law far more credit than Larry Harvey for sustaining the event and nurturing its DIY spirit in the early years.

“John did everything. Larry is no doer, he’s a thinker,” Dan said, a critique he extends to the whole organization that formed after John’s departure in 1996. “The LLC was just the people who were around Larry to help him make it happen.”

While there may be a kernel of truth to the criticism, Dan probably goes too far in denying credit to Larry and the LLC. If nothing else, Larry has long recognized that it’s the community that builds Black Rock City and the job of the LLC is mostly to facilitate that process, provide a basic infrastructure, and run interference with the authorities.

But Dan was probably right when he said, “The counterculture of the Bay Area resulted in Burning Man, not the other way around.”

“We made Burning Man because we needed it,” Dan said, explaining that it was an outgrowth of what was already a formative component of the Bay Area counterculture. “It was engrained in our psyches from a young age, in our very genetics.”

Dan started making art for Burning Man in 1997, a labor of love that supplemented his work doing commercial artworks during the dot.com era. “Then I started to get into bigger and bigger projects, and then started to actually make money from them,” Dan said.

He founded Headless Point Studios on Hunter’s Point in 1997, and when it burned down in 2003, he went looking for a new workspace and found American Steel. It was like a dream come true for an artist as ambitious as Dan, a block-long, 250,000 square foot facility with a dozen separate bays with entrances large enough to drive semis through, the high-ceilings criss-crossed with 18 bridges cranes capable of lifting whatever multi-ton masterpieces that artists could dream up.

“Who has bridge cranes, 20,000 square feet, and 40-foot ceilings? It was just amazing,” said Dan, who started dating and collaborating with Karen, a Flaming Lotus Girl at the time. “It’s one of the largest artist workspaces in the world.”

At American Steel, they learned to use the tools and facility as they built Passage, the evocative steel sculptures of a mother and daughter walking plaintively away from the Man, which debuted at Burning Man 2005. They rented one of the bays at American Steel and learned to do large scale pipe fitting from Vast Engineering, which occupied a neighboring bay, developing techniques for creating these 10-ton sculptures from steel cables, chains, and other recycled industrial materials.

“We didn’t really get them right, but we got the thumbs up for trying,” Dan said of Passage, steel sculptures of a scale that was new to the event, with a style they would hone and one that served as a template for later works, such as the figures that surrounded a massive wooden oil derrick in their 2007 piece Crude Awakening.

American Steel eventually came to be populated by these haunting, hulking figures that would reach down at you like the giant trying to steal Jack’s ax, stand sentry, look up in reverence, or strike other evocative poses. And despite their size, they have received subtle alterations over the years.

“We’ve installed Passage three times and each time I’ve made revisions,” Karen told me, referring to a run that included its placement at Pier 14 along the San Francisco waterfront in 2006, among the first Burning Man art installations to appear in the city where the event was born.

Along the way, Dan and Karen developed a strong reputation in the art world that they were helped to forge, as well as a large network of artists and other burners who wanted to work with them or chart their similar paths of creating large-scale artworks and the other festivals that were starting to solicit such pieces, such as Coachella, Bonnaroo, and Electric Daisyland.

By the time they were building Crude Awakening, the most ambitious project that Black Rock City LLC had ever funded, the footprint that Dan and Karen occupied in American Steel had grown from one bay to four. And still, they knew the demand was even greater within their community, so they decided to take a chance.

“This type of culture, we’re always looking for more,” Karen told me with a sly grin.

When they heard that the condominium project proposed for the American Steel site had fallen through, they talked to the owner of American Steel, who was open to the idea of leasing out the entire facility if their financials penciled out.

“Fortunately, we had been working with big projects for long enough that we had financials,” said Dan, who worked with Karen to develop a 25-page proposal for leasing the entire facility and renting out space to artists and small commercial ventures.

“We’re lucky the owner of the building let us just take over his property,” Karen said, chuckling as she noted that they signed the lease on April Fool’s Day. Since then, they have filled the facility with around 100 leases at a time, representing more than 400 artists using the space at once, by their estimation.

“American Steel is a product of Burning Man,” Dan said, noting how the event and the culture it fed have empowered a growing number of people to pursue their artistic ambitions. “Burning Man is about finding a vision of ourselves that we want to share,” Dan said.

Karen agreed that it’s exciting to be at the epicenter of a world of Burning Man artists coming into their own and realizing their dreams. “It’s happening, it’s emerging, and it’s pretty exciting,” she said.

And for this intriguing Burning Man couple, it was a risk, but one worth taking.

“We wanted to create something of value so we have something,” Dan said. “But if this didn’t work, we were ruined for many, many years.”

Who’s Really in Charge?

There had been many challenges to the leadership of the event, to Black Rock City LLC, by current and former attendees who felt it was their event as much as the Borg’s.

That tension had always been there, but it came fast and furious during the renaissance years, starting with the Borg2 rebellion in 2005, continuing the next year with John Law’s lawsuit, and the next when Paul Addis torched the Man early, and again the next year when people heckled the American Dream theme and were upset with the Borg’s role in sending Addis to prison.

But it wasn’t just the outsiders who raised concerns. Even the true believers, many of whom drew paychecks from the Borg and helped do its bidding, decried a leadership structure that didn’t seem to fit with the event’s hyper-collaborative nature.

Tom Price publicly evangelized Burning Man culture more fervently than anyone I knew. When he married Burning Man spokesperson Andie Grace in October of 2008 — with Reverend Billy officiating, all the Borg brass in attendance, and colorful Indie Circus performers livening up the event — it was like a Burning Man royal wedding.

But later, Tom told me that the Burning Man culture blossomed almost in spite of its leadership. “Mitigating against that is the absolute train wreck that is the management of the Burning Man event itself. I don’t think you could find a group of people that is less equipped and less likely to be running a multi-million-dollar corporation than the six people running Burning Man right now. And I think they’d tell you that themselves,” said Tom, who had been increasingly involved with the Borg since founding Burners Without Borders. “The great dichotomy is the event itself is a countercultural institution that is run in a way that is very traditional and the result of that has been enormous dynamic tension from inside the community aimed at the organizers of the event.”

If it can get its shit together, Tom said, Burning Man could be a big force for change. “But, having created these tens of thousands of newly empowered, self-actualized people, if it stumbles in that, the children will eat their parents just as readily as they will eat the dominant culture that they are raging against.”

While Burning Man has its “10 Principles,” Tom noted that those were really only guidelines that were developed 18 years into the event, and many burners aren’t even familiar with them. The event was really too vast to have a common purpose: “There’s the kids from Thunderdome, and Cuddletown, and the Japanese Tea Garden people, and on and on, and they’re all there mashed up on top of each other, and they all think it’s their place, and they’re all right. Because the things that they share in common, which is a decision to express themselves and a decision to tolerate the expression of others, is very rare.”

“Burning Man, I believe, happened organically as a response to the culture that we’ve created in this country over the last 40 years, that celebrated, even fetishized, consumption for its own sake. And people need an antidote to that. They needed a place where they could be decommodified. And now that capitalism is literally breaking at the foundations, there’s this tremendous appetite for an alternative,” Tom said during the Wall Street financial meltdown of late 2008.

Rebecca Anders saw that as well, noting how people continued to attend the event, expensive as it is, even as the worst economic downtown since the Great Depression kicked in. “I’d like to think that, as supposedly happened in the Depression era, that people coming to terms with real financial problems that are actually endemic in our society, maybe helps folks simplify their values and focus a little better on what’s truly valuable to them and truly worthwhile. You’re still spending retarded quantities of money making your crazy little art car and going out to the desert, but you’re saying it’s really important that I have my teeny weeny little triceratops car. This is really important that I make this crazy beautiful thing and show it to other people,” Rebecca said.

Times of unrest are great opportunities for positive change, and Burning Man represented many of the values that the country needed most. Rebecca saw that as deliberate: “It has gotten more mainstream, but that’s just a factor of it opening up and not being exclusive and so hidden and so underground. And that was an intentional move by the organization.”

But it’s probably closer to say that was an intentional move by the new generation of movers and doers that had filled in underneath the Borg — those who ran the regional events, the big art spaces, the volunteer networks — rather than the six people who were nominally in charge of Burning Man.

Consider Burners Without Borders, which by 2008, Carmen Mauk was running almost entirely as an autonomous organization yet under the auspices of the Burning Man business structure.

“You don’t need a lot of people to run a grassroots organization, particularly if you’re connecting people with other people,” Carmen said, noting that BWB operates under the fiscal sponsorship of Black Rock Arts Foundation, but is essentially an autonomous organization. “Burning Man pays me to administer, facilitate, direct this entire program with no oversight. Larry Harvey has never asked me one question about Burners Without Borders.”

That model is pretty standard within Black Rock City LLC, which stages the event, controls the brand, and encourages the creation of splinter organizations, from BRAF, BWB, and Black Rock Solar to the regional groups that operate all over the world, then basically lets them to do their thing.

“It’s an autonomous thing that people are running and that’s the real story about 2004 to now for me. It was sort of when the reins were given over to the people,” Carmen told me. “Like the shamans who go to the desert, we are now ready to bring this wisdom back to our real world, everyday lives, and do something significant with it. What’s that going to be? Well, it’s going to look like a lot of different things and Burners Without Borders is just one way to catalyze and organize some of those efforts.”

Facilitating Events

That can-do culture took many forms after the 2008 event, from the big and inspiring to the small and stupid, while Burners Without Borders continued to evolve. It responded to the massive earthquake in Haiti in early 2010 with supplies and relief workers, just as it had in Pisco, Peru two years earlier and to the Gulf Coast hurricanes two years before that.

“Burners Without Borders has become a beacon when something happens in the world and people want to help, in this community and beyond. Currently, with Haiti, we are a hub for communications with people who want to help,” Carmen told me shortly after the earthquake in early 2010. “So I’m preparing people now to go and work with them and then also be looking to see what else is needed. How is that burner specialty going to find roots here?”

But Carmen was doing even more work facilitating small projects and helping proactively hatch burners’ ideas, something she sees as the evolution of Burning Man, that turning outward to face the world after perfecting our little experiment in community-building.

“Most people when they come forward, they have an idea for what they want to do but they don’t know how to execute it. My experience before I came to Burning Man was executing big projects on big problems in the world internationally. And we also learned (how to find creative solutions to big problems) from Katrina, and we’re still learning in Peru, two years after that earthquake. So now we have a lot of connections that makes this natural ability this community has, to come forward and offer their skills, even more impactful,” Carmen said.

Carmen was actually not particularly happy that the organization has been so closely associated with disaster, but she recognizes that is a good way to generate media exposure and get support. And that translated into Burners Without Borders having about $15,000 in donations in the bank when they broke camp in Pearlington, so Carmen put out a call for projects seeking small grants.

“I put very little parameters, but people came back with really amazing projects,” Carmen told me in early 2010. “So last year we funded about 15 projects with only like $5,500, ranging from permaculture to helping kids get off huffing and off the street in Kenya. Four kids are now living in apartments and learning how to spin fire and then going into hotels and getting paid. Not even on the street, but dignified. Some woman just saved a lake for 500 bucks, to put in a graywater natural system where African women are using bad soap to wash their clothes and that soap is killing the fish, so they set up a system to make it stop. And I sent her that money in three days. There’s no middle man, there’s no bureaucracy, there’s nothing stopping you from being able to do what you want to do. And almost every single person and has said, omigod, I can’t believe how easy this has been.”

The Kenya project was a great example of the new spirit. Burner Will Ruddick, a former Peace Corps volunteer, was living in Mombasa, Kenya and met some desperately poor streets kids living in a park where he would spin flaming poi. They were interested in Ruddick and his fire, so he saw an opportunity to help them escape a dangerous life that included huffing paint thinner to escape their problems.

So, with input from the Burning Man Fire Conclave, he used materials found in Kenya to create flaming poi for the kids to use, and with a couple thousand dollars in support from BWB, Ruddick turned them into the Motomoto Circus, a fire performance troupe that did paying gigs in hotels in the region. Carmen said that’s a good example of how the Burning Man culture has changed and expanded.

“It’s much more international. When those folks go back home, they are having the experience that people say they have when they go to Burning Man, that their life is changed, that they now know who they are and they’re going to quit their jobs and do the person who are now rather than the job they thought they had to do for money,” she said.

And that has in turn drawn people to the culture who weren’t even familiar with Burning Man.

“What we saw in Peru is people came from all over the world, some of them having never heard of Burning Man. More people than burners supported our project in Peru and now they’re burners. Fifty people then came to Burning Man the following year after they had volunteered and they thought they were just going to come stay for a week and then leave and continue on their travels. And like everyone who came to Katrina that was a burner, people ended up staying longer, if they could, than they intended,” she said.

So the event is being fed by other aspects of what the Burning Man culture has come to represent: these counterculture figures — with their tattoos, piercings, artsy inclinations, and strange sense of recreation — doing good works in communities around the world. But Carmen prefers to see the situation in reverse, Burning Man finally realizing its potential as more than just a party.

“Now, people are seeing Burning Man as a celebration, but they feel compelled and accountable to this larger idea that we had to be doing something else other than putting on parties. And Burning Man has now seen that. It’s changed in the regional coordinators contract that they sign, that there have to be civic projects now and that’s what’s expected. The events and the parties, yeah whatever, that’s one way to gather people, but it’s not what’s expected,” Carmen said. “Now it’s shifted to: How is your community showing up and leading these principles and not just kind of copying what you thought you saw in the desert?”

Carmen, Rebecca, Tom, Chicken, and many other burner luminaries are relentless networkers, constantly expanding the community with key new connections. Carmen started working with Daniel Pinchbeck, a writer who does semi-monthly Evolver Spores workshops exploring life after money, a return to mysticism, and similar topics. He wrote a book on 2012 and the modern use of psychedelics, and he started to translate that into what he discovered at Burning Man.

“I’m working with them to make what we do even bigger and capture some of these folks — some who go to Burning Man and some who don’t — who are saying we have all these ideas about changing consciousness and how we’re going to change the world, but what are we going to do? A lot of people have all these ideas and they don’t know how to land them,” she said.

And her list goes on and on, from the burner who worked on the BWB project in Peru then went home and started European Disaster Volunteers — “It was basically because of BWB that he created this organization, that he felt like he could. You know, that Burning Man feeling, like I can do anything,” Carmen said — to working with Kostume Kult, Figment, and other New York City burners to create a burner-certified business network called OK Culture.

“It’s a label to verify how people are doing business,” Carmen said, noting that she’s actually gotten a bit of pushback on the idea from the Borg, which is wary of wading into anything that seems like a commercial venture. “Larry is scared to death of this.”

It’s understandable, particularly after the burner community backlash to some of the business partnerships that popped up around the Green Man theme. But many longtime burners were also looking for a way to sustain what they were doing, and that means developing some revenue sources for the members of this decommodified culture, because there are practical limits to volunteerism.

“It’s an immature relationship that we have to commerce. Commodification is one thing, but commerce is another,” Carmen said. “And as Burning Man is starting to put more businesses on the JRS (Jack Rabbit Speaks email blasts) and promote people who are doing work, anything from EL wire to whatever, it’s starting to change.”

In fact, that were many manifestations of the Burning Man culture that had made the jump to mainstream acceptance without losing track of where they came from.

Playa-born Mutaytor Keeps Rockin’

Mutaytor might be the ultimate Burning Man tribe, an eclectic group of Los Angeles-based performers who came together on the playa more than a decade ago, forming into a band that’s like a traveling circus that evangelizes the burner ethos and culture everywhere they go, just by being who they are: sexy, scruffy, wild, warm, colorful denizens of the counterculture.

Mutaytor is perhaps the most popular and iconic musical act to emerge from Burning Man, a group whose spirited performances on and off the playa reflected and helped to shape and define the culture that birthed them. And if that’s not enough cultural cred, many of the two dozen members work for Burning Man in various capacities, from building Black Rock City with the Department of Public Works to forming the backbone of event’s regional network in Los Angeles.

My path has crossed Mutaytor’s many times, from watching them play at my first Burning Man in 2001 to joining them on the burner-dominated Xingolati cruise ship in 2005 to later being invited in March 2010 to watch them record their fourth album, “Unconditional Love” in the sprawling Westerfeld House, a Victorian mansion on San Francisco’s Alamo Square that is the legendary former home to such countercultural figures as Satanist Anton LaVey and members of the Manson family to noted ‘60s promoter Chet Helms’ Family Dog Productions and the band Big Brother and the Holding Company.

The house is now owned by Jim Siegel, a longtime Haight Street head shop owner and housing preservationist who did a masterful restoration job, showing a striking attention to detail. Siegel owns the Distractions store on Haight Street, one of the few walk-in outlets for buying Burning Man tickets, and became a friend of the Mutaytor family in 2004.

Although the dancers and other women who perform with Mutaytor weren’t at this recording — Siegel said they usually prance around the house topless and lend a debaucherous energy to Siegel’s house — he still loves the energy that the band brings when it invades his house: “It reminds me of my hippie days living in communes.”

Buck A.E. Down — a key band member, singing and playing guitar, as well as producing and arranging their songs — said the album and accompanying documentary film is Mutaytor trying to build on a career that began as basically a pickup group of musicians and performers on the playa.

“We’re a total product of that environment,” Buck said of Mutaytor’s musicians, dancers, acrobats, fire spinners, aerialists, thespians, producers, culture mavens, and facilitators of the arts. “We’ve been underground for 10 years and have a voluminous body of work.”

Mutaytor tapped the lingering rave and emerging Burning Man scenes with a mix of electronica-infused music and performance art to develop a distinct style and loyal fans. “So, between that and Burning Man, we developed just a ravenous following.” With this built-in fan base of burners and ravers, Mutaytors was able to start getting gigs in the clubs of Hollywood, San Francisco, and other cities that had significant numbers of people who attended Burning Man.

“We became a very recognizable and tangible part of that culture,” Buck said, noting that burners sought out Mutaytor to plug into the feeling of Black Rock City, if only for a night in their cities. “What we were able to do is provide that vibe.”

Christine “Crunchy” Nash, Mutaytor’s tour manager and self-described “den mother,” said that Larry Harvey has been very encouraging and supportive of Mutaytor, urging them to essentially be musical ambassadors of the event and its culture. “That’s one thing Larry said to us is I want to do this year round and that’s what we’re doing in LA,” Crunchy said. “Most of the people in the band have been going to Burning Man for more than 10 years.”

Buck added, “We’re like the Jews, the wandering Jews,” which totally cracked up the group, but I understood what he meant, particularly as he went on to explain how the burner tribes are scattered through the world, but they retain that essential cultural connection.

Particularly down in Los Angeles, where the Mutaytor crew regularly works and plays with other Burning Man camps, from the Cirque Berserk performers and carnies to longtime members of my own camp, Garage Mahal, Crunchy said their extended tribe really is a year-round, active community of burners.

“It really is like we are there in LA and we just pick up and move to the playa,” she said.

Crunchy said they have family-like connections in San Francisco — to such businessman-burners as Jim Siegel and JD Petras, who both have sprawling homes where the band can stay — and in cities around the country that have big, established Burning Man tribes, from New York City to Portland, Oregon.

“It’s the movers and shakers of the San Francisco community and others that have allowed us to survive as we’ve tried to make it,” Crunchy said. “It has made traveling so much easier because we have places to stay at many places we play.”

Buck said that was essential to their survival: “You take that kind of culture away from Burning Man and we would have broken up a long time ago, or we wouldn’t have even formed.” Just as Mutaytor is rooted on the playa, its members also wanted to root this album in a special place and immediately thought of the Westerfeld House.

“There are just places where stuff happens, just certain environments that are special places,” Buck said, noting that Mutaytor is made up of musical professionals — from session players to sound guys at venues like the Roxie and for concert tours — who have three recording studios at their disposal among them, but they chose to do the recording here because it felt magical and personal to them.

“We had an epiphany on the road and decided we just had to record it here,” Buck said, adding how well the decision has worked out acoustically. “Rather than just recording the band, we want to record the house. That’s how we’ve been miking it up.”

Each room on the group floor was filled with musical instruments and recording equipment, and Buck said excitedly that they have been resonating with this 150-year-old building: “We’re getting some of the best tones.”

Granddaddy of the Sound Camps

By 2008, Opulent Temple had been on the corner of Esplanade and 2 o’clock for four years, longer than any sound camp had held onto such a high-profile corner. But then again, most big sound camps only last a few years at Burning Man before they burn out and fade away, mostly because of the cost and difficulty of throwing the party.

Syd Gris didn’t give up on dealing with that dynamic and in 2009, he made another run at Black Rock City LLC, trying to get them to allow sound camps to apply for art grants, and kick down some free tickets — something, anything. OT and other big camps, such as Sol System and Root Society, were spending $50,000 per year or more to stage the event’s nightlife, and Syd felt like he had finally made some headway with the board.

But then Larry arrived back from a trip to Africa and nixed the deal. “Larry called me to say this is not happening, and it’s not happening because I don’t like it, and I don’t like it because I think it complicates the process. So my read was it makes their life harder, so they don’t want to deal with it,” Syd said.

Had they recognized the importance of the sound camps, “There could be more diversity of nightlife options,” he said in 2009. El Circo wouldn’t have left the event, nor Lush, Illuminaughty, or The Deep End. Syd even considered pulling the plug on OT, but he just couldn’t, not with the way they were still rocking it.

In 2008, the camp hosted legendary DJ Carl Cox, the latest new arrival to Burning Man among the world’s top DJs. “I had heard about Burning Man many years ago, as Paul Oakenfold was talking about it and he was saying that it would be the best thing you would ever go to, as it was a real eye opener. That was 15 years ago, so I had known about it then and ever since then I have been trying to get myself there,” Cox told me. “I have been to many festivals around the world as you can imagine, but my impression of this was just out of this world.”

In fact, Cox was so affected that he named his next album Black Rock Desert, promoting it with Burning Man photos and references that caused a conflict with the Borg, which insisted that he make some changes to honor its copyrights, a dispute that Syd helped to mediate. Cox was truly taken with the event and seemed to quickly understand its ethos.

“The thing here is that you truly have to make the festival into whatever you want out of it. At a rock or pop or even techno festival, you would go there to see a band or DJ play, but at Burning Man, people go to meet other people with similar interests and let their hair down, which is refreshing,” Cox said. “This festival is like nothing I have ever been to.”