e couldn't get a job. He was a carpenter, they would not give him any work, and they did everything to destroy him till he died.” This is what Bromley Armstrong said about Hugh Burnett's life after the events described in this book.

e couldn't get a job. He was a carpenter, they would not give him any work, and they did everything to destroy him till he died.” This is what Bromley Armstrong said about Hugh Burnett's life after the events described in this book.

Justice finally came to Dresden on November 16, 1956, when a group from the National Unity Association went into Kay's Café and Morley McKay served them.

A story written by the Canadian Press news service on December 25, 1956, told of a

… happy story about the town where the original Uncle Tom was buried. It's told by two Negroes who emerged smiling from a restaurant where they have always been rebuffed. They said they were served as would be anyone else.

Clearly, times had changed, and the citizens of Dresden had the law on their side. In defeat, the likes of Morley McKay, Anne Emerson, and James Ford faded into the life of the town, melting into the fabric of Dresden's history.

But many attitudes didn't change. In Dresden, the goal of changing behavior was achieved when the courts upheld the Fair Accommodation Practices Act. But it didn't necessarily mean that people's attitudes improved. So while justice had been served in the town, the leader of the National Unity Association was never able to fully enjoy it. Because of the long fight, Hugh Burnett's business had suffered. He lost clients and even some of his friends. People who were angry about the court decision refused to give him any work. They turned away from him on the street. When Hugh visited former clients, they said there was nothing they could do for him.

Despite, or maybe because of, his efforts to bring justice to Dresden, by the late 1950s Hugh Burnett had to leave his hometown.

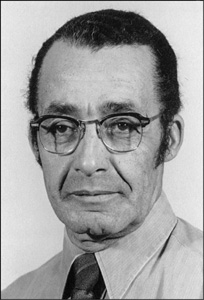

Courtesy of the Burnett family

Hugh Burnett was forced to leave Dresden, looking for work. He moved to London, Ontario, in 1957. Over the next thirty years he worked for a number of companies and continued to run his own carpentry business. The remainder of his life was lived out of the public eye. He died in 1991. His body was cremated and his ashes buried in a plot he shares with his parents in the Dresden Cemetery.

Morley McKay would continue to operate his restaurant for several more years. On a cold day in January 1972, McKay, the man who came to symbolize the anger and resentment of Dresden's white community, died. He was buried in the Dresden Cemetery, not far from Hugh Burnett.

In the capital of Toronto, Premier Leslie Frost led the province of Ontario into a new age, as Canada began to emerge as a significant leader in the world. In addition to championing human rights, he laid the groundwork for advances in education and health, and encouraged growth in private industry. In 1961, he retired from public office. Far to the east of Dresden, in the town of Lindsay, Ontario, the man who brought the issue of fairness into the province's political forum and made it into law lies in his family grave, where he was buried in 1973. The small-minded small-town values that folks in Dresden spoke of so often, the “leave-us-alone” attitudes that tried to defeat fairness in the town, were struck down by a small-town premier whose political life was based on his own set of pragmatic and visionary values.

For the National Unity Association, there was recognition for its work from human-rights organizations. The NUA would continue to support other challenges to equal treatment, such as workplace discrimination and the refusal to rent apartments on the basis of skin color. But its work was winding down. As time went by, the group slowly disbanded. By the early 1970s, it was officially no longer an association. In 1973, the Ontario Human Rights Commission held a dinner for the group, and each member was given a Certificate of Merit.

And the other founders of the National Unity Association? A part of the community like the rich earth and the green crops that surrounded Dresden, like the history that began with lumber barons and a brave black man named Josiah Henson they stayed on. They were hardy souls who carried within them the quiet knowledge that they had done the right thing, and they passed their wisdom on to the next generation. They would come to rest in the pages of Dresden's history, their energy, determination, and action becoming a part of the collective memory of a town, a province, and a country.

The work of the National Unity Association and the Joint Labour Committee created an important precedent, helping set the stage for the establishment of the Ontario Human Rights Commission. Daniel G. Hill husband of Donna Hill, the former secretary of the Joint Labour Committee was the Commission's first chair.

The Commission was established in 1961, and continues to be responsible for Ontario's Human Rights Code. Created in 1962, the Human Rights Code protects Ontario citizens from discrimination in employment, accommodation, goods, services, and facilities, as well as in membership in associations and unions. The Ontario Human Rights Commission continues to investigate all cases of discrimination against Ontario's citizens.

The other civil-rights groups that rallied to Dresden's cause continued their work: challenging government to enact better policies for allowing the immigration of non-whites to Canada; keeping an eye on police forces and their treatment of minorities; and pushing for fairness in employment and accommodation.

Fifty years later, the activists remember this dramatic time. Donna Hill said it was the most exciting and challenging time of her new life in Canada. For Ruth Lor, it was a chance to really take action against racism, and it just made sense to her to be a part of that history. Alvin Ladd, the last surviving founder of the NUA, said it was justice that was a long time coming.

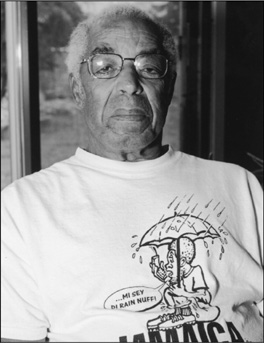

Bromley Armstrong, now retired, worked in Dresden and other places to challenge discriminatory attitudes in the 1950s. John Cooper

For Bromley Armstrong, the significance was driven home when the National Film Board went to Dresden to make a film, Journey to Justice. An eighty-seven-year-old black man saw the cameras, recognized Armstrong and Ruth Lor (who was with him) and approached and hugged them both. With tears in his eyes, he said that as a child he couldn't buy an ice cream cone anywhere in the town. He spoke of his father and his grandfather being refused service everywhere, and how generations of blacks grew so used to the words “No Service.” Armstrong and Lor took the old man to lunch, on the very street where it all took place, moving freely along the avenue that once screamed a silent and resounding “NO” to so many of Dresden's citizens.