Entry and Exit

Praise of civility can be dreadfully “wet,” as noted, offering little more than the injunction to be nice. That has not been the case so far in this book: the origins of civility lay in viciousness, while its maintenance largely rests on competitive emulation and depoliticization. Beyond all this, however, stands the serious but less obvious weakness identified by John Murray Cuddihy in The Ordeal of Civility.1 This brilliant book casts a searching light on “civility” by analyzing how outsiders experienced its standards, with concentration in his case on the Jewish experience in the modern era.

Let me proceed inductively, by means of an example that will lead to more general reflections.2 One of the greatest intellects of the postwar era, Ernest Gellner was born in 1925 and raised in Prague to a family with a Jewish background (felt more by the mother than the father) and within a world in which the greatest loyalty was owed to the Czechoslovak state headed by Tomáš Masaryk, to whom particular allegiance was given because he had fought against anti-Semitism. Gellner’s identity was more Czech than Jewish, but the latter identity was present—first in his schooling and massively so when it was imposed upon him by the horrors of mid-twentieth-century Europe, which drove him into exile in 1939. After fighting in the war, and going into what seemed like permanent exile in Britain in 1946, this brilliant and highly ambitious young man wanted to “get in,” to succeed. But getting in was not so easy. The English upper classes of the time painted him as Eastern European, too clever by half and far too interested in sex—or so he felt that he was seen, and actually portrayed in an unpublished novel by one of his close friends. If there was wry amusement for Gellner in this, followed by an embrace of homelessness, there was also at times very great resentment. Some of the latter sentiment was directed at his colleague, Michael Oakeshott, who disliked “rationalists” and waxed lyrical about the benefits of tradition. Tradition would, of course, permanently exclude those who did not know the rules, so Gellner loved to mockingly quote passages from Oakeshott, such as this, which so clearly exemplified a civility that was narrow at best and racist at worst:

Like a foreigner or a man out of his social class, he is bewildered by a tradition and a habit of behavior of which he knows only the surface; a butler or an observant house-maid has the advantage of him.3

Further resentment was shown toward Isaiah Berlin, whose background was not dissimilar to his own, on the grounds that he had accepted such local standards, thereby abandoning his allegiance to truth and reason.

In the course of the nineteenth century, the closed world of the ghettos was coming to an end. Interest could be shown to this world, not least by Franz Kafka, but in the end there was a general movement away from it. Many sought complete assimilation, hoping to merge into the local norms, often by changing name and religion. But insiders could often recognize those wanting to get in, and so could make life difficult for them: differently put, anti-Semitism increased in force throughout the century. And the problem was not faced just once; rather, the influx of the less-educated Jews from the East made the dilemma continual, often to the irritation of those who felt themselves to have already assimilated successfully. In these circumstances another general route emerged: the call for universal standards by thinkers with Jewish backgrounds. Cuddihy’s claim is that Marx and Freud took this route. An equally stunning example is that of the large number of early Bolsheviks of Jewish background whose discovery that they were not wanted in nationalist movements led them to become left-wing empire-savers.4 Then there is the famous treatise by Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, a superlative call for universalism filled with distaste for nationalism of any sort. This suggests a final option, that of Jewish self-identification and pride, seen above all in Zionism. One reason for this option is straightforward: specifically, that universalism failed, and many of those who called for it were killed.5 Just as important is the feeling that denying one’s roots was a form of self-mutilation, with those so doing often being accused of “self-hatred.”6 This last sentiment can amount to such communal disapproval as to make it hard for one to leave, an additional burden to the obvious problem of communities not wanting to allow entry.

Gellner’s social theory as a whole endlessly revolves around the tension caused by the importance of context-free inquiry and the human desire for a measure of cultural belonging, with his real claim to fame lying in his attack on any thinker who embraced only one of these poles rather than seeking some way to swim between them.7 I certainly share his general philosophical position, and insist on underlining the certain fact that the dilemma is real—and with application well beyond that of the Jewish community. But the purpose of introducing the issue here remains simple. Is “civility” in fact so loaded with cultural flavor and baggage that it is not neutral and desirable? This supposition would certainly add real bite to the question. Might it not be the case, as one reader of the manuscript of this book suggested, that my argument is terribly English? After the English civil war, something of a cultural norm arose in which it became impolite to talk about politics and religion, and possibly sex as well, which didn’t leave much but the weather to animate conversation. And I can add the personal irritation of my partner, who at times insists, somewhat to my surprise, that life with an Englishman is by no means easy, for hints have to be taken as statements, while abhorrence is shown to open conflict.

The best way to gain some purchase on this issue is to analyze the general call for cultural pluralism (held to be desirable when contrasted to homogeneity), which is purportedly achievable only by force and held to be the result of the imposition of a particular, rather than a universal, set of standards. This seems to be the language of tolerance, even liberty. Let a thousand flowers bloom! Surely no decent person could argue to the contrary? I do claim decency, yet I reject a good deal of this general position. Mild jokes might be in order at the start. For one thing, it is noticeable that the cry for difference is uniform, singular, and homogeneous! For another, claims for difference often accompany assertions that the world is becoming globalized! More seriously, there is certainly a good deal to be said against difference insofar as it fades into complete relativism, surely the last refuge of the scoundrels of the modern world. The argument that follows can best be seen as offering generalized, sociological skepticism toward the claim that social processes are such that multicultural loyalties are replacing more national identities. But the center of attention focuses on an empirical comparison between the contemporary United States and Europe, and leads to considerable praise for the American way of life.8 Here is a situation in which, as we shall see, less is more.

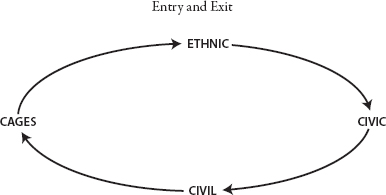

Conceptual clarity can be gained by dissecting the celebrated notions of civic and ethnic nationalism, not least as this will suggest a schema that differentiates options of belonging. We should not accept everything that is implied in the formula ethnic/bad, civic/good. For one thing, there is nothing necessarily terrible about loyalty to one’s ethnic group—and this sentiment in fact underlies the supposedly civic nationalism of the French. For another, civic nationalism is not necessarily nice: its injunction can be “join us or else.” This was certainly true of the way in which Paris treated La Vendée during the early years of the Revolution, and it remains at the back of the contemporary “affaire des foulards.” Put another way, civic nationalism may be resolutely hostile to diversity. This suggests the following scheme.9

Moving clockwise around this circle allows a series of theoretical points to be made.

Ethnic nationalism is indeed repulsive when it is underwritten by relativist philosophies insisting that one should literally think with one’s blood. Much less horrible is the combination of ethnic and civic nationalisms represented by France—that is, a world in which one is taken in or allowed in as long as one absorbs the culture of the dominant ethnic group. Civic nationalism becomes more liberal when it moves toward the pole of civility, best defined in terms of the acceptance of diverse positions or cultures.

Whether this last move is, so to speak, sociologically real can be measured by asking two questions. First, is the identity to which one is asked to accede relatively thin; that is, does it have at its core political loyalty rather than a collective memory of an ethnic group? It is helpful to remember in this context that the most interesting of Ernest Renan’s views about the nature of nationalism was his claim that the success of any nation depended on its capacity to forget a good deal of the past.10 Second, are rates of intermarriage high? In other words, is the claim that one can belong regardless of one’s background borne out by the facts?

All this is obvious. Less so, perhaps, is a tension that lies at the heart of multiculturalism. In the interests of clarity, matters can be put bluntly. Multiculturalism properly understood is civil nationalism, the recognition of diversity. But that diversity is—needs to be, should be—limited by a consensus on shared values. Difference is acceptable only as long as group identities are voluntary, that is, insofar as identities can be changed according to individual desire. What is at issue is neatly encapsulated, as already noted, in the notion of caging. If multiculturalism means that groups have rights over individuals—if, for example, the leaders of a group have the power to decide to whom young girls of the community should be married—then it becomes repulsive. Such multiculturalism might seem liberal in tolerating difference, but it is in fact the illiberalism of misguided liberalism and diminishes life chances by allowing social caging. This view is, of course, relativist, and it is related to ethnic nationalism in presuming that one must think with one’s group. Importantly, the link to ethnic nationalism may be very close indeed. If there are no universal standards, and ethnic groups are held to be in permanent competition, then it is possible, perhaps likely, that one group will seek to dominate another.

If these are ideal typical positions, a powerful stream of modern social theory in effect suggests that some have greater viability than others. A series of thinkers, interestingly all liberal, have insisted that homogeneity, whether ethnic or civic, is a “must” if a society is to function effectively. John Stuart Mill made this claim when speaking about the workings of democracy, insisting that the nationalities question had to be solved in order for democracy to be viable.11 The great contemporary theorist of democracy Robert Dahl has reiterated this idea.12 The notion behind all this is straightforward. Human beings cannot take too much conflict, cannot put themselves on the line at all times and in every way. For disagreement to be productive in the way admired by liberalism, it must be contained—that is, it must take place within a frame of common belonging. To a great extent, the same insight underlies David Miller’s view that national homogeneity is a precondition for generous welfare regimes.13 This is correct: the generosity of Scandinavian countries rests on the willingness to give generously to people exactly like oneself. But the great theorist of the need for social homogeneity was, of course, Gellner, who argued that homogeneity was necessary so that industrial society can function properly. That Slovakia and the Czech Republic have prospered apart rather than suffering together might seem to support his view.

Skepticism has already been shown to the view that nations cannot live together under a single political roof. But a good deal more illumination on this issue, and on the possibility of civil nationalism, can be given by turning to the United States and to Europe, a comparison in surprising ways to the advantage of the former.

There are at least two obvious and powerful reasons for turning to the United States. First, the United States deserves far more study than it receives, and not just in relation to the topic presently under analysis. For one thing, America is the greatest power that the world has ever known. At present it spends about 50 percent of the world total of military expenditure, giving it continuing power over the international market—that is, over such economic rivals as Japan and the European Union. For another, it is the world within which talk of difference is insistent, even deafening. This may, of course, be no accident. The historic uniqueness of the United States perhaps lies in the fact that it was formed through immigration, that it is a polity created from difference. Of course, that very formulation suggests that America has been a melting pot, homogenizing the many into a single unit. Was that true? Is it still true today?

The answer to that question must be wholly affirmative.14 But recognition of a sociological reality does not require moral endorsement. Hence, consideration of the harsh side of the melting pot is needed before turning to fundamentally meritorious social practices that allow American nationalism to move beyond its dominant civic core toward elements of genuine civility.

The United States is not a social world that favors diversity. An initial consideration to that effect lies in the simple fact that white Anglo-Saxon settlers more or less exterminated the native population, thereby establishing their own hegemony.15 African Americans received treatment nearly as vicious. Further, the creation of the new state placed a very strong emphasis on uniformity. For one thing, a Constitution was formed, a singular set of ideals created, which thereafter was held to be sacred.16 For another, the United States was created by means of powerful acts, usually directed from below, of political cleansing. A significant section of the elite that had supported the Crown—in absolute numerical terms larger than those guillotined in France during the Revolution, and from a smaller population—was forced to leave.17 Canada thereby gained an element of that anti-Americanism that comprises the key part of its national identity.

Perhaps the most striking general interpretation of American history and society—that proposed by scholars such as Richard Hofstadter, Daniel Bell, and Seymour Martin Lipset—is that which insists on the power of these initial ideas, of continuity through continuing consensus.18 This is not quite right. If some alternatives were ruled out at the time of foundation, others were eliminated as the result of historical events. The two most important examples deserve at least minimal attention.

First of all, we ought to remember that the United States remained unitary only as the result of a very brutal civil war. The Constitution had, of course, recognized the different interests of the slave-owning Southern states, but the difference between North and South grew in the early years of the Republic. The works of John Calhoun amount to a myth of hierarchy on the basis of which a new nation might have been formed. War destroyed that diversity, with Lincoln trying at the end of the conflict to create unity by means of such new institutions as Thanksgiving. Of course, the South did not lose its cultural autonomy simply as the result of defeat in war but maintained a key hold on federal politics well into the 1930s. Nonetheless, over time the South has lost its uniqueness, especially in recent years, as the result of political change and of population and industrial transfers from North to South. And in this general area of nationalism, it is well worth noting that there is no possibility of the United States becoming a multinational society. No one wants a second civil war of visceral intensity. Furthermore, Americans are overwhelmingly opposed to the idea that Spanish should be recognized as a second official language. The toughness of American civic nationalism was seen in the quip of Miriam A. Ferguson, the governor of Texas who opposed the introduction of bilingualism, that if “English was good enough for Jesus Christ, it ought to be good enough for the children of Texas.” This is surely one element ensuring that Spanish is quickly being lost as a second language, as was the case for languages of other immigrant groups in the nineteenth century.

The second alternative vision was that of socialism, in one form or another. Revisionist history makes it equally clear that there was a genuine socialist stream of ideas and institutions in American history, represented most spectacularly in the militant unionism of the International Workers of the World. Further proof of the strength of working-class activism can be found in the bitterness of labor disputes, which resulted in a very large number of deaths, second only to those at the hands of the late czarist empire.

This is all to say that American ideals of individualism and enterprise were not so powerful or so widely shared as to rule out a challenge. Their ascendancy came about, as noted, for two fundamental reasons. On the one hand, the fact that citizenship had been granted early on meant that worker dissatisfaction tended to be limited, to be directed against industrialists rather than against the state, thereby limiting its overall power. On the other hand, and crucially for this argument, socialism was literally destroyed, as is made apparent by that very large number of working-class deaths. The recipe for social stability, as argued, is often the combination of political opening with absolute intolerance toward extremists. Certainly this mixture worked in the United States, ensuring that it would thereafter be bereft of any sort of social democratic tendency.

The rosier and milder face of the coin of American homogeneity can be seen at work in American ethnic relations. A warning should be issued before describing a remarkable American achievement. Everything that will be said excludes African Americans, whose position inside the United States remains heavily marked by racial discrimination. The hideousness of what is involved can be seen in situations where the vast majority of middle-class African Americans who strive to “get in” by being economically successful often experience bitterness when they discover that integration does not exist in the suburbs to which they move.19 But for the majority of Americans, ethnic identity is now an option, not a destiny imposed from outside.20 Rates of intermarriage are extremely high, not least for the first generation of Cuban Americans in Florida, more than 50 percent of whom marry outside their own group. Ethnic identity has little real content. It is permissible to graduate from kindergarten wearing a sari as long as one does not believe in caste—that is, as long as one is American. There are severe limits to difference.

Societies are complicated, so it makes sense to summarize what has been said by placing the United States at several points of the schema that has been provided. It is not the case that the United States has been completely free from ethnic nationalism. The colonists destroyed the native inhabitants. Furthermore, some part of the identity enshrined in the Constitution reflects the British background of the initial majority. Nonetheless, the United States does score firmly in the civic camp. The harshness of its civic culture can be seen in the destruction of alternative visions. But the United States has moved toward a civil position: American identity is less Anglo-Saxon than it was, given the capacity of Americans to create new national narratives with ease, while still more important are the astonishing high rates of intermarriage already described—for all but Afro-Americans, of course, whose life chances remain scandalously impoverished. In contrast to these points of reference, a particular absence must be very clearly set. All those books and treatises, the polemics of despair, asserting that the United States is falling apart because multiculturalism is becoming, in our terms, caging and illiberal are woefully misguided. It might very well be terrible were the relativism of politicized identity cages so complete as to destroy any sense of a common culture. But this is not the case. What matters about identity claims in the United States is that they are at once without content and so very generally made. They represent yet another moment of America’s startling ability to create a common culture. This is a remarkable society, but it is not one of great difference and diversity. The powers of homogenization in the United States—deriving as much from Hollywood and consumerism, of course, as from the factors examined here—remain intact. The melting pot still works, but it has a particular character. Its homogeneity is “lite.” There is little caging of ethnicity, and a rather small and happily ever-changing set of beliefs to which adherence is required. If one wished to criticize this achievement, it would be to stress how limited diversity is within the United States.21 But one’s worry in this regard fades when remembering that an exception to all this is, as noted, race—an area in which there is a good deal of caging and about which one further point must be made. Welfare provision exists in the United States, but it is more limited than in Europe because of race: the refusal to share with people judged not to be one’s fellows, the result for many years of the votes of the “Solid South,” limited provisions and distorted them in many ways.22 To have this situation in such a rich country is morally scandalous, but a sociologist must also note that it makes it easy for immigrants to enter—they have little to claim, and so cause limited resentment.

In contrast, there has been nothing “lite” about the European situation. Furthermore, critical problems exist today, and this despite advances in some countries. Little will be found here, as noted, to justify European anti-Americanism, a continuing sentiment that is far too self-satisfied for its own good.

It may be useful to preface the comments to be made by highlighting, in different words, a point already made about the nature of nationalism. Although it is well known that the great theorists of nationalism came from the world of Austria-Hungary, insufficient attention has been paid to Sigmund Freud. What matters about his work is less the particular views expressed in Moses and Monotheism than that an argument can be made on the basis of his view of the libido. That peculiar substance is seen to be sticky, capable of attaching itself to different objects, which then lend it a particular character. So it is with nationalism. This protean force is licentiously labile, gaining its character from the social forces with which it interacts. Let us consider three highly stylized, ideal typical moments of nationalism in modern European history, since to do so will advance the argument.

The first stage is that of simplicity and innocence. Nationalism was linked to liberalism. The Old Regime represented a common enemy. A typical figure in this regard is John Wilkes, the editor of the North Briton and the somewhat flawed champion of popular representation. To mention the Highland Clearances in Scotland is to note that nationalism at this time had some hideous moments of forced homogenization. Nonetheless, this period, best represented by Britain, was relatively benign. The sociology of the situation was simple: the state had come before the nation. The centralization of feudalism played a large part in the creation of a single language early on, to which varied groups acceded over a long period of time. The second stage is that of horror and viciousness. Here nation came before state in the composite monarchies of the Romanovs and the Hapsburgs. In these empires—and in that of the Ottomans—varied ethnic groups gained self-consciousness, thereby turning ethnic diversity into genuine multinationalism. This often made for great difficulties, notably when national and social inequalities were combined. Nonetheless, multinational arrangements were not necessarily doomed by socioeconomic pressures coming from below. On the contrary, many nations merely sought the affirmation of their historic liberties, with the Slavs being somewhat scared of secession given their geopolitical placement between Russia and Germany. But exit became attractive in the course of time because of state policies of linguistic and cultural homogenization that were designed to copy the leading powers by making nation-states out of diverse materials. The third period is the one of modesty described in chapter 3. This is the world of economic interdependence, of trade rather than of heroic adventure.23 This is not for a moment to accept the claim, made so often these days, that the nation-state is dead.24 Still, the mood of the nation-state has changed. Abandoning the attempt to be complete power containers has increased security. Doing less has proved to give more.

One should and can claim that a great contemporary European achievement, aided by the United States, is the newfound ability of several countries to live together without recourse to war. Competition between these states remains, of course, not least given the presence of different political economies within Europe and of different standards of success between them, but this does not alter the fact that sustained dialogue between the countries has been established. This is no longer anarchy but a society of sorts, dominated by elites and with a good deal of nativist resentment coming from below, from those unable to swim in this larger sea. One should not exaggerate this achievement, as the crisis surrounding the euro makes clear. Still, there is diversity within Europe between different countries. But the situation within European societies is altogether less happy.

To begin with, we should remember that in 1914 something like sixty million people lived in states not ruled by their own “coculturals.” Today there are very few examples of successful multinational regimes west of the Ukraine—Spain, for sure, idiosyncratic Switzerland as well, but with Britain and Belgium in the midst of fairly severe challenges. Much of the discussion of multiculturalism is in a sense hypocritical: we speak the language of tolerance now that we have no great national divisions to deal with. This is not to deny the bittersweet fact that democracy works more easily in most of Europe, including much of Central Europe and the Balkans, precisely because forced homogenization has taken place. Equally, it may well be the case that national homogeneity helps flexible economic adjustment. This seems to be true of Denmark, although the core of homogeneity was achieved in that country well before the twentieth century.25 This does not for a moment justify or call for forced homogenization, not least as there are cases—Greece comes to mind—where its legacies remain toxic. And one should anyway be rather cautious in this whole area. It may well be that national homogeneity allows for flexible adjustment, but the extent to which it encourages innovation is open to question.

More important is the marked failure of many European countries to integrate into their social fabric the immigrants that their low fertility rates make necessary. Such immigrants are physically present, very often wishing to belong, but they remain excluded in the ways that count.26 Housing patterns and low marriage rates of immigrants into the host community demonstrate this in the clearest manner possible. So too does the rise all over Europe of right-wing parties directed at immigrants, which very often show particular hostility to immigrants from Muslim countries. It is very noticeable that countries with a long history of national homogeneity—Denmark being a prime example—have especially great difficulty in this regard. Recent legislation in that country has a very particular character: it is leftist in wishing to preserve high welfare benefits for Danes but right/nationalist in wishing to deny such benefits to outsiders. It would be idle, perhaps sad to say, to imagine multiculturalism in a country with such a homogeneous past, but the worrying thing is the tacit refusal to allow those present to move from their status as “new Danes” to becoming Danes.

There are some causes for optimism in Europe. Political design has successes to its credit. It looks as if the complex consociational agreements designed for Northern Ireland will work. Ukraine is holding together precisely because there is no attempt to homogenize the country in linguistic terms.27 Most Spaniards seem content with multiple identities, and it matters little, in any case, if Spain—or the United Kingdom or Belgium—were to dissolve, as long, that is, as the separable units could remain within the European Union. After all, this is a struggle over a single passport, a single European citizenship. But one should not exaggerate here. Consider Switzerland.28 Here we do have the important example of a multiethnic nation, or, in an alternative formulation, a successful state-nation. But the fact that different ethnicities live together does not for a moment mean that the country as a whole is open to outsiders. Very much to the contrary, contemporary Swiss politics is as concerned to exclude outsiders as is that of Denmark.29

To summarize the argument, civil nationalism is profoundly to be desired, but it is also rather hard to achieve. It is interesting to discover that the United States is more of a pioneer in this regard than are European countries. But both these great areas of the North have at their respective hearts a good deal of background homogeneity. In conclusion, we can realistically hope that the non-European world may manage its affairs better by invention rather than by imitating the North. We have already seen that the ingenuity of the linguistic regime of India that allows this huge country to remain united. It is possible to have multiple identities and to create consociational and federal arrangements that allow several nations to live within a single political frame. Also, the presence of a large number of ethnic groups, perhaps one hundred and twenty in Tanzania alone—none of which is near demographic dominance—can undermine homogenizing politics: multiethnic coalitions may be mandated, given that no group dares play the ethnic card. Of course, Africa has seen little sustained interstate war since decolonization, though it has been plagued by low-intensity internal strife—and by more recent resource-driven conflicts. A negative side of the absence of sustained geopolitical conflict has been relative failure in state-building.30 But there is another, more positive side to the picture. One factor that intensified ethnic cleansing in Europe was competing claims to a single piece of territory. Near-absolute endorsement of the principle of nonintervention has meant that this factor has by and large been missing in Africa. Of course, none of this is to say, once again, that sweetness and light can be guaranteed.

1 J. M. Cuddihy, The Ordeal of Civility: Freud, Marx, Levi-Strauss and the Jewish Struggle with Modernity (Boston: Beacon Press, 1974).

2 J. A. Hall, Ernest Gellner: An Intellectual Biography (London: Verso, 2010), especially chapter 3.

3 M. Oakeshott, Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays (London: Methuen, 1962), 31, cited in E. A. Gellner, Legitimation of Belief (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974), 4.

4 L. Riga, “The Ethnic Roots of Class Universalism: Rethinking the ‘Russian’ Revolutionary Elite,” American Journal of Sociology 114 (2008).

5 M. Hacohen, “Karl Popper in Exile: The Viennese Progressive Imagination and the Making of The Open Society,” Philosophy of Social Sciences 26 (1990).

6 P. Birnbaum, The Geography of Hope: Exile, the Enlightenment, Disassimilation (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008).

7 E. A. Gellner, Language and Solitude: Wittgenstein, Malinowski and the Hapsburg Dilemma (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

8 The emphasis on “contemporary” is deliberate and important. Slavery has been the great horror of the history of the United States, and its legacy remains powerful, as will be carefully stressed in the rest of this chapter. So the scope of generalizations made here is limited; it does not include a discussion of race.

9 I recognize that this is a limited scheme, designed in largest part to contrast the situations of the United States and the European Union. Perhaps the biggest omission in the scheme is its failure to capture new transnational identities—that is, it does not reflect the new experience of migrants able to return to and communicate with their homeland with relative ease. The most interesting research on such immigrants suggests that they belong neither to their homeland nor to their new host country but rather sit interestingly, if uneasily, between both—a situation that happens to be my own. On this see Towards a Transnational Perspective on Migration, ed. N. Glick Schiller, L. Basch, and C. S. Blank (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1992); The Changing Face of Home, ed. P. Levitt and M. Waters (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002); and S. Vertovec, “Migrant Transnationalism and Modes of Transformation,” International Migration Review 38 (2004).

10 E. Renan, “What Is a Nation?,” in Becoming National: A Reader, ed. G. Eley and R. G. Suny ([1882] Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

11 J. S. Mill, Considerations on Representative Government (London: Parker, Son and Bourn, 1861), chapter 16.

12 R. Dahl, Polyarchy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977).

13 D. Miller, On Nationality (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

14 The arguments that follow are presented in greater detail in J. A. Hall and C. Lindholm, Is America Breaking Apart? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999).

15 M. Mann, The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

16 It may seem that the diversity allowed in religious practice contradicts the point being made. This is not really so, as is most evident once we note that Americans today trust those who have a religion—any religion—while showing suspicion toward those who have none.

17 R. Palmer, The Age of Democratic Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959), 1:188–202.

18 The clearest statement of this view is now S. M. Lipset, American Exceptionalism (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996).

19 Hall and Lindholm, Is America Breaking Apart?, chapter 10.

20 M. Waters, Ethnic Options: Choosing Ethnicities in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

21 M. Weinfeld (Like Everyone Else … But Different: The Paradoxical Success of Canadian Jews [Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2001], chapter 6) is aware of this, and makes much of the contribution of Jewish communities to genuine diversity because their traditions can at times be strong enough to maintain a genuine way of life. He recognizes and endorses some limited amount of social caging as necessary to community maintenance.

22 I. Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Discrimination in Twentieth-Century America (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005).

23 I am playing here with the title of Werner Sombart’s analysis, at the start of the century, of Germany’s geopolitical choice (Händler und Helden [München: Leipzig, 1915]).

24 A. Milward, The European Rescue of the Nation-State (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992); P. Anderson, “Under the Sign of the Interim” and “The Europe to Come,” in The Question of Europe, ed. P. Gowan and P. Anderson (London: Verso, 1997); A. Moravcsik, The Choice for Europe (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998).

25 J. L. Campbell and J. A. Hall, “Defending the Gellnerian Premise: Denmark in Historical and Comparative Context,” Nations and Nationalism 16 (2010).

26 G. Schmidt and V. Jakobsen, Pardannelse Blandt Etniske Minoriteter I Danmark (Copenhagen: Socialforskningsinstituttet, 2004); T. Shakoor and R. W. Riis, Tryghed Blandt Unge Nydanskere (Copenhagen: Tryg Fonden, 2007).

27 In this context there is much to be said for distinguishing “national” from “holding together” federations, as explained by A. Stepan, J. Linz, and Y. Yadav, Crafting State-Nations.

28 A. Wimmer, “A Swiss Anomaly? A Relational Account of National Boundary Making,” Nations and Nationalism 17 (2011).

29 A. Wimmer, Nationalist Exclusion and Ethnic Conflict: Shadows of Modernity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), chapter 8.

30 J. Herbst, States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).