Chapter 17

THE ICU “LITE”

Before actually going home, I would need to stay in a transitional room at Mount Sinai. I started to hear rumors about the luxury oasis known as Eleven West. Eleven West, I was told, was the place where Cleopatra would have been recovering had she had a craniotomy at Mount Sinai Hospital. During Jim’s visits, I was spending most of my precious time with him pleading to find a way to get me out of the ICU. He was painfully aware of my suffering and he wanted to bring me some relief. Since he couldn’t whisk me away to a beachfront resort on the shores of Thailand, he started talking about Eleven West. If you were lucky enough to find yourself a patient recovering in Eleven West at Mount Sinai Hospital, according to the brochure, you would be treated to “private suites, a gourmet kitchen, daily afternoon tea, and soaring views of Central Park.”

I could see it in my mind. In fact, it was all I could picture. Jim was determined to get me a room there. Nothing was too good for his ninety-pound-half-head-shaved-tube-fed-multiperforated queen.

When the time drew near for me to leave the ICU to go into this transitional phase of my recovery, I was beyond disappointed to learn that I didn’t qualify for Eleven West. I required a level of care that denied me access to this white-collar prison section of the hospital. However, I was assured that I would have a similar resort-like experience in Eight West, which was near the neurosurgery ICU and therefore adjacent to all the specialty care still required in my multitube existence.

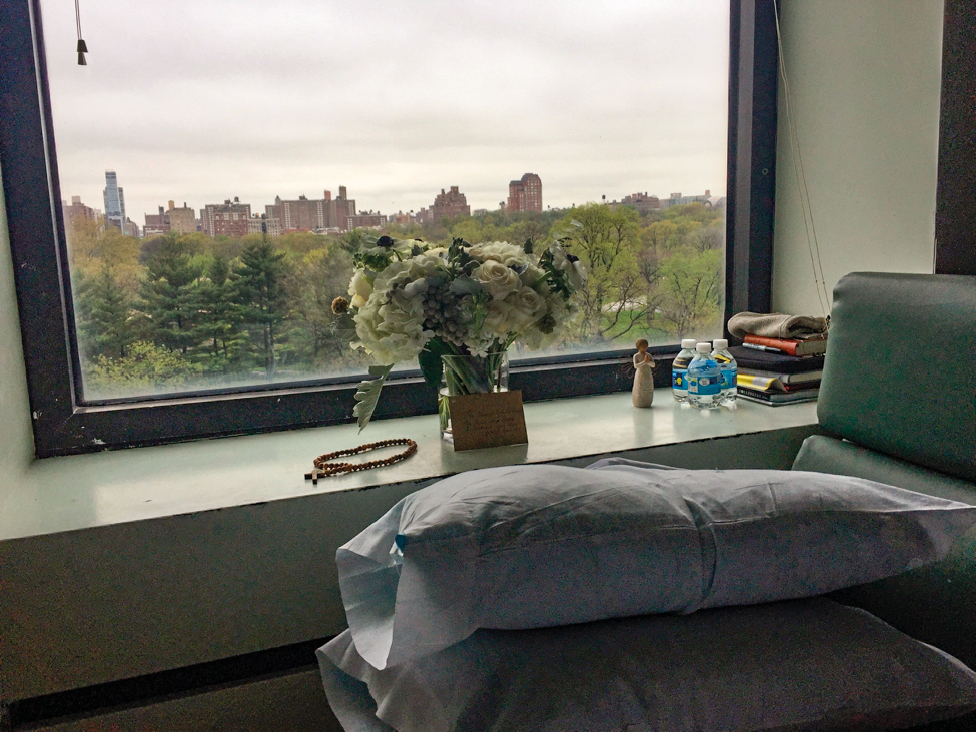

Eight West was a tiny private room with a small window (did I mention there were no windows in the ICU?). It did indeed have a view of Central Park, if you walked over to it and looked straight down. But it was a room. An actual room! Not a multiple-patient area divided by curtains with people moaning in pain and crash carts crashing all night. Also, there were flowers allowed (did I mention there were no flowers allowed in the ICU?), and the flowers came pouring in. A note about flowers in the hospital: If you happen to be lucky enough to be someone’s primary caregiver in the hospital, part of your duties should include moving flowers to where the patient can see them, and also throwing them away when they die. There’s nothing worse than waking up in a room surrounded by dead flowers (see Rick Grimes waking up in the first episode of The Walking Dead).

Also important is to let the patient know who sent the flowers, and to record the names of those people, because inevitably when the patient finally gets out of the hospital, any of those who sent flowers might ask, “Did you get my flowers in the hospital?” only to be met with a blank stare that says, “I don’t remember,” and they will respond back with a look of disappointment. At this point, you’re probably saying to yourself, What an ingrate! She’s complaining about people sending her flowers and not having a nice Central Park view?! but truth be told, I would have been overjoyed at leaving the ICU and landing in Eight West had it not been for the concept of the elusive Eleven West beckoning to me like a beautiful siren to a sailor lost at sea.

The thing I was most grateful for about moving to Eight West was that, theoretically, my children could visit me. This started a serious debate. Jim was hesitant about this happening. He was afraid of traumatizing the kids. At this point they had put a speaking valve in the trach hole in my neck so I could wheeze-talk.

JEANNIE (wheeze-talking): Jim! Thank God I am out of the ICU! When can you bring all the kids to see me?

JIM: Jeannie, I don’t know if that’s the best idea right now. They are really happy with Gramma Weezie.

JEANNIE: But I miss them and I want to see them as soon as possible, please!

The force of her voice blows the plastic valve across the room, where it hits the wall and click-clacks to the floor.

JIM: I don’t know, Jeannie, you don’t really… I’m not sure if they should see you right now.

In other words, I looked like death warmed over. There was a playground within eyeshot of my window with the straight-down view of Central Park. Jim compromised, saying he could bring the kids there and they could look up at me in the window, close enough to see it was me, but far enough not to see that I was breathing through a hole in my neck. “Look, everyone, there’s Mommy! Doesn’t she look great from that window eight flights up across the street?” I would wave at them and they would wave at me, and no one would be traumatized—except me, of course, but I was already traumatized.

If you look straight down, there’s a playground.

Upon giving this plan some thought, I expressed to Jim that I felt, with every molecule of my being, that it would help my healing immensely if I could touch our children. I didn’t want to be selfish. I didn’t want to traumatize anyone, but I really needed it. I felt that if Jim carefully explained the situation, warned them, at least the two older kids would comprehend that how I looked now was only temporary. Marre was still out of the country on her epic class trip. I barely remembered her brief visit to the ICU that Jim had finagled. She’d come in for like five minutes while I was barely conscious. I’d opened my eyes and saw her sitting on the edge of my bed with a weak, scared smile on her face, and then I must have fallen asleep. That left Jack, who was eleven. He was old enough to understand how I looked and why. Jim decided that Jack made the cut, and he would bring him to Eight West to see me after school the next day. The long train ride up would be great father-and-son alone time and give Jim a chance to prepare Jack. I advised him to describe me as a hideous monster, so gruesome that by the time Jack walked in, I would look like a supermodel.

If I were to try to describe how long it took for the next day to arrive, it would take up three chapters. So I’ll spare you the excruciating anticipation of this visit, but as I was waiting, I envisioned spending time with each of my kids. Kissing Patrick’s palm when I dropped him at nursery school. Shampooing Michael’s curly hair in the tub and forming a Christmas tree on top with the suds. Making up formulaic Scooby-Doo stories with Katie where she was central to the mystery and inevitably the one who pulled the mask off the scary witch, revealing that it was just the greedy hotel clerk. Lying on Marre’s bed, holding her in my arms and rubbing her back while she cried hot tears of preteen angst. Jack, my little monkey, my Dennis the Menace. Chasing him around the house to get him to brush his teeth. I would always start out mad, but by the time I caught him we would both collapse in gales of laughter. Jack is a handful, but despite his naughty capers, I’m captivated by his odd humor and offbeat way of thinking. I remembered the time in church when I observed Jack gazing up at an elaborate stained-glass window, an angelic, peaceful look on his face. I wondered what profound, spiritual thoughts were going through his head. He turned to me and with the innocence of a cherub asked, “Mom, do zombies poop?” When would he get here? I was dying inside.

Jim finally brought Jack in and the part of me that had felt dead sprang back to life. He was wearing a blue polo and blue pants that were way too similar in color. It was a monochromatic abomination. Obviously, his mom hadn’t dressed him in weeks. Normally this would have bothered me, but now I thought he was perfect. A huge, wide-eyed, concerned smile spread across his face as he dropped his backpack and came right over and gave me a hug. He smelled like dirt and Fanta. It was the best thing I’ve ever smelled. Without thinking, I licked his cheek. It tasted like dirt and Fanta. He didn’t seem to care at all.