Somewhere in Continental Europe. Two women in their 30s are touching up their make-up in a chi chi restaurant bathroom. The brunette takes a little spray bottle out of her handbag, pulls up her A-line skirt and sprays her inner thigh. The other woman raises her eyebrow and the brunette smiles, explaining, ‘I’m on a date. It’s Eros Breeze . . .’

Given recent technological advances, the increase of understanding in neurobiology, and our sex-fuelled culture, it’s difficult to even imagine the potential future of postmodern libidos. Will it be a world of teledildonics, where we use computers to control sex toys over long distances? Will treatments be available to stop physical ageing, to keep our bodies young and beautiful and sexually appealing? And will a chemical concoction crack the ‘crisis’ in women’s sexuality and make us want to fuck even after a long day’s work?

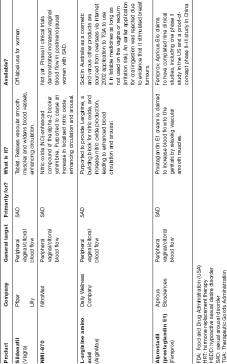

At present, there are a number of drug options for women experiencing sexual problems. Besides ecstasy. But almost all of the drugs targeting female libido aren’t on sale at a pharmacy. Many desire enhancers are currently being trialled—for the second or third time—while most have been flat-out rejected by regulators such as the Australian TGA (Therapeutic Goods Administration) and the FDA (the American Food and Drug Administration) because they haven’t been considered safe or effective enough for public consumption. In other words, we’re close, but no cigar.

Upon deeper investigation, though, it is clear that many doctors prescribe sex drugs ‘off label’, without knowing their true effectiveness or long-term health effects. ‘Off label’ refers to the use of a legally available drug for an unapproved purpose. Off-label use is extremely common. A 2001 study showed that 21 per cent of total prescriptions in the US were off-label, and that approximately 73 per cent of all off-label use had little or no scientific support.1 While it is legal and common for physicians to prescribe off-label drugs in most countries, it is illegal for pharmaceutical companies to directly promote drugs for off-label use. But this is poorly policed, and companies take advantage of grey areas in legislation and enforcement. In the US between 2003 and 2008, federal prosecutors and state attorneys-general brought more than a dozen cases against drug makers for off-label marketing and won more than $6 billion in criminal and civil settlements.2

It is almost certain, however, that a sexual cure-all is on its way to a pharmacy near you. Not usually a gambling woman, I have a number of reasons to be confident in saying so. First off, given the success of Viagra, finding its female equivalent is an obvious goal. Second, the number of drug-company-backed scientists in hot pursuit of a sexual fortifier for women is similar to the backing received for walking on the moon—lots of hard science, lots of hard cash. Third, a whole new discipline has been created called ‘sexual medicine’. Fourth, the sophisticated state of current brain research promises discoveries about where lust and desire are located in the human brain and how to amplify them. This will inform the creation of a sexual elixir that changes not only our body’s reaction to stimuli, but how we think about that reaction. It’s likely that research on hormones and blood flow will also become more compelling. Fifth, marital sex has become the bedrock of measuring marital happiness, with divorce or adultery a common response to lack of sexual satisfaction. Sixth, our sexuality is becoming increasingly medicalised, treated as though it were a medical condition requiring intervention. Too many people believe the hype that a low libido is a dysfunction. Dysfunctions, of course, require drugs, and there is little doubt that the future will bring a cornucopia of pharmaceutical potions. After all, seventh reason, we are already doped up. We are already used to taking drugs that tamper with our hormones and central nervous system. We are already used to a body supplemented by the artificial. From designer foods to designer dogs to designer babies to designer brains to designer Viagra penises, we left nature a long time ago. Sex drugs are part of our common landscape: the contraceptive pill and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) are now ordinary aids in our complicated modern life, and not seen as the strange and miraculous chemical compounds that they are.

As a culture, we are becoming increasingly medicated. Add too the devastating effects of antidepressants on libido, and the alarming number of people on antidepressants, and there is cause for global concern. Our bodies are unarguably less aligned with nature than at any other time in human history. Where once we were pioneers of land and sea, now we are pioneers of consumption, used to absorbing substances that alter our normal bodily function, be they Valium, Zoloft, or the plethora of pills we are prescribed for illness and to fight off the ravages of ageing.

Like postmodern brothels, the pharmaceutical companies produce increasingly more sophisticated and alluring drugs. Nootropics, for example, aka ‘smart drugs’, work to improve cognitive abilities, such as memory, concentration, thought, mood and learning. Some nootropics are now being used to help people regain brain functioning lost during ageing, and to treat diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

New markets are also being found for existing drugs. Beta blockers, originally prescribed for conditions such as angina and hypertension, are commonly used by musicians and actors to reduce stage fright. Ritalin, the drug used to treat ADHD, is being taken by exam-cramming uni students to improve concentration during all-nighters.

And so medicine has replaced magic, and doctors and lab researchers have replaced the shamans and herbalists of yesteryear. We can turn a man into a woman, stop female fertility, alter melancholy, and reverse hormonal changes associated with menopause so that women feel 35 again.

Well, then, what can the enterprise of medicine do for our tired, lagging libidos?

Female sexual ennui is a problem pharmaceutical companies believe they are in the best position to solve. Next we will look at some of the drugs designed to resurrect female desire. These are either available at the pharmacy, under trial, steadily being worked upon in the race to develop—and patent—the perfect concoction or abandoned . . . for now. As we will see, many drugs experience rebirth, and are used in different ways, for different purposes, by different companies. These drugs described in the chapter are a mixed bag in terms of safety and efficacy. But trust me, one of them, or a close relative, will come out on top, and get us on top.

Sex drugs—blood flow

Viagra, Cialis, Levitra

In the mid-1990s, researchers at Pfizer were testing an experimental drug for angina and made an interesting discovery . . . their male subjects were experiencing persistent hard-ons. Flash forward to 1998 and Viagra (sildenafil) hits the market, changing the play of sex forever. Originally meant to redeem a medical problem, it became the lifestyle drug. Viagra, however, wasn’t an overnight success. It took several years for both the medical establishment and patients to become comfortable with it, and millions of marketing dollars to turn it into a household name with blockbuster sales.3

Since Viagra’s entrance to the scene, followed by its groupies Cialis (tadalafil) and Levitra (vardenafil), drug makers have been searching for a female equivalent. Viagra was the first in a class of drugs known as phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, which increase blood flow to the genitals by raising levels of nitric oxide, which encourages relaxation and dilation of blood vessels. Given erectile dysfunction is considered more of a physical problem than an emotional one, Viagra works well for many men.

Limited research has shown that women who take Viagra experience increased blood flow to the vagina and clitoris.4 Some research has indicated that Viagra may reduce the adverse side effect of sexual dysfunction in women taking SSRI antidepressants.5 However, many of these studies were conducted with small sample sizes, or used inappropriate statistical tests or dubious non-validated assessment tools.6 Interestingly the same names often appear as authors of these studies, most notably the Berman sisters—Laura and Jennifer, who were named ‘the face of FSD’ in the documentary movie Orgasm, Inc.. The Bermans’ have become widely criticised for their close ties with Pfizer, who paid for the studies they developed and conducted on Viagra’s effects on women.7 When asked by Time magazine about her portrayal in Orgasm Inc., Laura said ‘I’ve never felt an ounce of pressure to create specific results or frame things in a certain way’, and ‘I really see the pharmaceutical companies as an ally’.8

In a 2008 paper, researchers Susan Davis and Esme Nijland write that the Viagra studies of the Bermans and Basson9 suggest that ‘this therapy may be useful for some women with genital arousal disorder rather than the larger group of women with low desire and subjective arousal’. They conclude that ‘large studies of PDE5 inhibitors in the general population have been disappointing’.10

So although Viagra may turn women on physically (getting us wet), it doesn’t turn us on mentally. Physical arousal doesn’t necessarily translate into wanting sex.

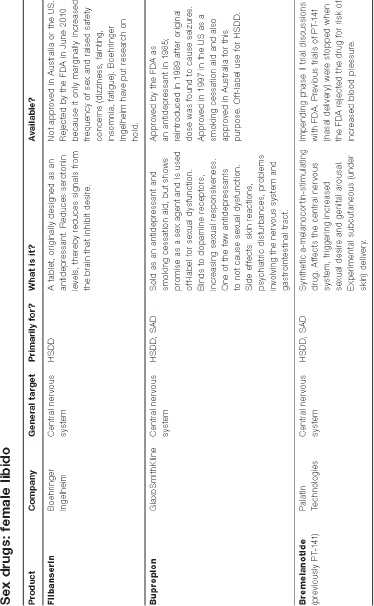

Sex drugs: hormone supplementation

A number of factors affect the balance of hormone levels over our lifetime. Some are age related, such as the relatively sudden changes in oestrogen levels that occur with the onset of menopause, as well as the slower and less perceptible decline in women’s androgen levels from our 30s onwards. (Androgens are hormones that create secondary male sex characteristics such as facial or body hair, thicker skin, increased muscle mass and deeper voice. The leading man of androgens is testosterone.)

Other hormonal changes may occur as a result of disease or surgery. These include hypopituitarism, hypogonadism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and the removal of ovaries and other reproductive organs. Some hormonal changes arise from taking the oral contraceptive pill. Hormone replacement therapy also has a significant effect on our hormones.

We now turn our attention to the pharmaceutical treatments currently being used to alter hormone levels in the body, and then some leading edge hormone research.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

The contraceptive pill is not the only drug relating to our sexuality that’s become an international habit. Women disturbed by the naturally ageing body can purchase seemingly magical drugs to alter their hormonal make-up. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) involves supplementing the body’s natural hormones. It is commonly used for menopause and, not so commonly, for transgender therapy and androgen therapy in men and women. Younger women with premature ovarian failure or surgical menopause may also use HRT until the age when natural menopause would likely occur.

HRT has been controversial, with medical professionals flip-flopping over its risks and benefits for the past five decades, from thinking it’s gold, to poison, and back again.

HRT aims to treat the discomfort caused by diminished circulating hormones in surgically menopausal, peri-menopausal and, to a lesser extent, postmenopausal women. It increases levels of the hormones the ovaries have stopped producing, mainly oestrogen and progesterone. Oestrogen and progesterone are prescribed in a variety of combinations, and sometimes testosterone is also added in the hope of increasing sex drive, restoring energy levels and preventing osteoporosis.

HRT is often given for short-term relief from menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, irregular menstruation, night sweats, vaginal dryness and urinary symptoms. Studies comparing HRT with a placebo show strong evidence that HRT is effective for such symptoms.11

HRT can be delivered by way of patches, tablets, creams, troches, IUDs, vaginal rings, gels or, more rarely, by injection.

Evidence shows that HRT may improve some aspects of sexual function, such as a reduction in dryness; oestrogen therapy can also have a positive effect on brain function and mood factors that affect sexual response.12 That said, some research also suggests that HRT has a negative impact on libido (as well as depressive effects). A 1997 study found that an increase in oestrogen arising from oestrogen-containing pills inhibits androgen production in the ovaries.13 Other researchers found oestrogen therapy binds up free testosterone, hence lowering its availability, and possibly leading to low sexual desire.14 (More on androgen deficiency a little later on.)

HRT is plagued by controversy. In the 1960s bestseller Feminine Forever,15 Robert Wilson framed menopause as an oestrogen-deficiency disease, preaching that all peri-menopausal women should take oestrogen for the remainder of their lives rather than face the inevitable ‘living decay’. Women listened. This idea of preserving youth and beauty through HRT has been promoted more recently by pharmaceutical companies in advertisements that ‘convey the message that oestrogens are a cure-all for the anxious, wrinkled, sexually frustrated older woman who has to compete in this era of cocktail parties, sexual freedom and errant husbands’.16

Then, in the 1970s, oestrogen replacement therapy was found to increase the risk of endometrial cancer. Talk about bad publicity. So doctors stopped prescribing HRT. Jump ahead a few years, and new studies showed some health benefits if oestrogen was combined with progesterone. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, many doctors went back to prescribing HRT, telling their patients it would help prevent heart disease. Nevertheless, HRT was now recognised as having both positive and negative effects.

Attitudes towards HRT changed again in 2002 when the US National Institutes of Health announced that women receiving a form of HRT called Prempro (conjugated equine oestrogens and a progestin) had a larger incidence of breast cancer, heart attacks and strokes. As a result of these findings the Journal of the American Medical Association recommended that women with natural (rather than surgical) menopause should take the lowest feasible dose of HRT for the shortest possible time to minimise risks.17 Millions of women immediately went off HRT. Cold turkey.

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial, conducted from 1993 to 1998, evaluated the effects of conjugated equine oestrogens on the incidence of chronic disease among postmenopausal women (age 50 to 79) who had had a hysterectomy. The trial was stopped a year early because of an increased risk of stroke. At the time it was concluded that this treatment should not be recommended to prevent chronic disease in postmenopausal women.18 However, because treatment effects differed by age, follow up was required. In the WHI follow-up study though 2009, it was found that younger women (age 50 to 59) receiving conjugated equine oestrogens had slightly lower risk of coronary heart disease and other diseases. Also, oestrogen use was not associated with excess risk for stroke or other problems such as deep-vein thrombosis, hip fracture and colorectal cancer.19 Today it is understood that oestrogen-alone therapy is safe for as long as six years for young menopausal women (age 50 to 59) who have had a hysterectomy.

As for oestrogen plus progestin (E+P), the WHI trial found that Prempro—the combination of conjugated equine oestrogens and medroxyprogesterone—was associated with coronary heart disease and breast cancer.20 The trial was stopped after the coronary heart disease and breast cancer risks were found to exceed the benefits. For every 10,000 women taking E+P, 41 women each year will develop breast cancer, as compared to 33 women per year who would develop breast cancer while taking a placebo. Also, the breast cancers that developed in women taking E+P were larger and more advanced; about 25 per cent had spread to lymph nodes or elsewhere in the body, compared to 16 per cent in women taking a placebo.21

There have also been cases of accidental exposure to HRT. An increasing number of hormone gels, creams and sprays are associated with cases in which users unwittingly exposed children and pets to HRT hormones. For instance, in 2010, Acrux, the Australian manufacturer of Evamist (an oestrogen spray for relief of menopause symptoms) warned women not to use their product in front of children or pets. This warning was issued after its American arm reported at least 10 cases of exposure to pets and children, resulting in children aged three to five displaying symptoms of early puberty, including enlarged breasts and nipple soreness.22 Evamist was approved in the US in 2007, but is yet to be approved by Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration.

Designer hormones

Although HRT usually comprises synthetic one-size-fits-all drug combinations such as Premarin, Prempro, and Provera, women in the US are increasingly opting for bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (HRT), with celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey, actress Suzanne Somers and Robin McGraw, the wife of talk-show host Dr Phil, fronting the trend.

Using an individualised approach, blood tests are taken to determine the woman’s hormone levels. (Other tests—on urine, saliva, hair follicles—can also be conducted.) Then a calculated dosage of bioidentical oestrogens, progesterone, pregnenalone, testosterone and/or DHEA is prescribed and prepared, usually at a compounding pharmacy. The patient is then monitored through regular follow-up hormone tests to ensure symptom relief is maintained at the lowest possible dosage.

Celebrities are endorsing bioidenticals as the new fountain of youth.

Suzanne Somers’ 2004 book The Sexy Years: Discover the Hormone Connection—The secret to fabulous sex, great health, and vitality, for women and men touts the benefits of bioidenticals as ‘natural hormones’.23 Robin McGraw appeared on Oprah alongside menopause guru, Dr Christiane Northrup in 2010, and also sang the praises of bioidentical hormones. Her 2008 book What’s Age Got To Do With It? details her personal journey to hormone balance. So there’s another item to add to the list: work–life balance, emotional balance, and now, hormonal balance. But unlike the others, you can buy this type of harmony.

Fans of bioidenticals extol the use of hormones not just to combat menopause, but as lifestyle drugs to minimise health risks, improve quality of life (for now at least—forget any long-term consequences) and to ensure that, like Peter Pan, we never grow old. It is believed that bioidenticals can make women feel young again and restore their hormone levels back to those of a 30-year-old. The ethos is clear: take charge of your health and buy back your youth, your soft skin, your wet vagina, your sex drive.

Amazingly, Robin McGraw has also got her hubby, Dr Phil, on these controversial drugs. She writes:

. . . after everything I learned about my own body, I learned a few things about Philip’s, too, and that’s when I started him on supplements. He trusts my research and hard work so much that he takes whatever I suggest (and feels a lot better for it), and he even lets me drag him to have his blood drawn every once in a while.24

Holy smokes.

The answer to McGraw’s quest to manage her hormones came in the form of The Hall Health & Longevity Center in California, and its founder Dr Prudence Hall, whose motto is, ‘Anyone who has a low hormone should have it replaced.’25

Hormone replacement, then, is for everybody. In fact, for optimal living, McGraw says we should all start monitoring our hormones in our . . . twenties! That way, she adds, by the time menopause comes along, we probably won’t have any symptoms at all. Apparently premenstrual syndrome, irregular or heavy periods, weight gain or exhaustion can all indicate hormone imbalance or thyroid problems—and as McGraw says, ‘A little fatigue or weight gain here or irritability or bloating there makes it [life] even harder, and it doesn’t have to be that way.’26 She even took her 30-year-old daughter-in-law to Dr Hall to get her hormones managed.

The American bioidentical advocate Christiane Northrup has found a clever way of undermining conventional HRT, specifically Premarin.27 In addition to focusing on its known risks and side effects, she often repeats that Premarin is synthetic, unnatural and made from horse urine.27 She implies that the one-size-fits-all approach of conventional HRT means you are not in control, not treated as a unique person. Northrup appears to be tapping into the fashionable preference for ‘green and natural’ products. But the fact that we already have a chemical in our body does not necessarily make it right or safe to add more.

With conventional HRT there are risks. The risk with bioidenticals is that we do not know the risks: no studies exist on their long-term effects. Also, when drugs are made up, or compounded, at a pharmacy, they are not necessarily approved in that form by the regulator, so buyers have to trust the pharmacy’s quality-control standards. In 2008 the FDA warned seven American pharmacy operations that their claims about the safety and effectiveness of BHRT were unsupported by medical evidence and thus considered false and misleading. Northrup believes that transdermal (skin) patches are the most physiologically appropriate way to take hormones, but this presents an increased risk to children and others who may accidentally put on or come in contact with a patch. Assuming bioidenticals are safe is potentially dangerous, especially given the track record of standard HRT.

Moreover, as Dr Wulf Utian, head of the North American Menopause Society, states, ‘There’s no such thing as a natural hormone. They’re all made in the lab, one way or another.’28 He advises going with conventional drugs, which are approved by the regulator, and on the lowest possible hormone dose. But with a little digging you find that Utian has financial links to a number of pharmaceutical companies—so if you were feeling sceptical you might think the doctor had a reason or two to pitch conventional, patentable HRT.

Certainly Northrup believes much of the resistance to bioidentical hormones stems from the lack of incentive for pharmaceutical companies to produce something that cannot be patented. She also refers to the potential low price of bioidentical formulations: Dr Joel Hargrove’s dropper-bottle approach (hormones dissolved in propylene glycol) can cost as little as $70 per year.29

Despite the known and unknown dangers of BHRT, it seems to be on a fast track to mainstream popularity. Perhaps one day there will be hormone servicers like ATMs that, with an instantaneous prick, measure our blood or saliva and pop out a little tube of perfectly concocted hormone cream to make us more ‘us’ and less old—and, for an extra fiver, give us a shot of antidepressant optimism spray.

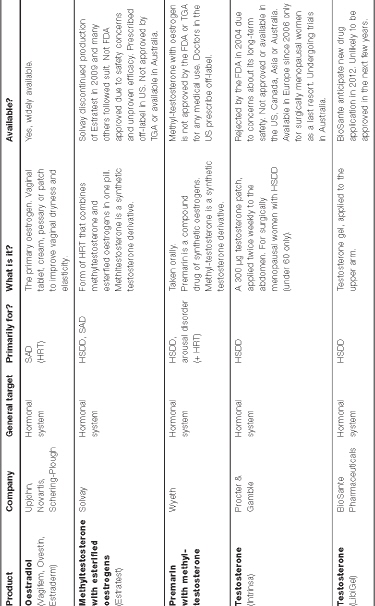

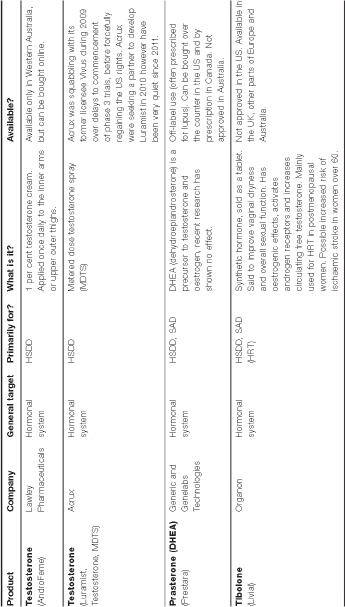

Androgen therapy

There is a lot of fuss in the field of sexuality about testosterone. A number of medical practitioners, scientists and pharmaceutical companies believe that women’s low libido can relate to low levels of androgens, including testosterone.

In women, androgen levels do not appear to fall suddenly with natural menopause as oestrogen levels do, but decline with increasing age—most likely owing to reduced production in the ovaries and lessened adrenal function. Total circulating and free (available) testosterone in women in their 40s is about half that in women in their 20s. Hence age-related androgen loss may occur in women in their late 30s and 40s.30

Other things that can lead to androgen loss include the use of oral contraceptives (the Pill) and oral oestrogens (HRT), hypopituitarism, adrenal insufficiency, ovarian insufficiency, glucocorticoid therapy and oophorectomy (surgical removal of one or both ovaries, which makes testosterone levels fall by as much as half within 24 hours of surgery).31

Androgen deficiency is highly controversial and nebulously defined as, ‘Complaints of a diminished sense of wellbeing, persistent unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, sexual receptivity and pleasure by a woman who is oestrogen-replete and in whom no other significant contributing factors can be identified.’32 Note there is no testosterone level specified, as a lower limit of ‘normal’ has not been established—and ‘even within a so-called normal population there is a wide range of normality’.33

Some researchers believe female androgen deficiency can cause symptoms such as lethargy and loss of sexual interest. Others do not think there is a link between testosterone levels and low libido. Others again think the condition, if it exists at all, is too poorly understood to treat safely.

Testosterone replacement for men has been available since the 1930s, particularly for those suffering from hypo-gonadism (decreased functioning of the gonads), and men who have lost their testicular function to disease, cancer or other causes, giving rise to the medical term andropause and its pop culture counterpart, manopause. Androgen therapy has been shown to increase alertness, wellbeing and lean muscle mass, and enhance libido and the ability to achieve erection. For decades, men with low sex drives have been prescribed products containing large amounts of the hormone. However, it also has some adverse effects, such as increasing a man’s red-blood-cell concentration (potentially leading to conditions such as heart attack and stroke). It has also been associated with sleep apnoea, acceleration of pre-existing prostate cancer and, in rare cases, liver toxicity.

There are several testosterone products for sale via patch, tablet, pill, cream, long-acting depot injection or the more recently developed buccal system (a patch applied to the upper gum). Apparently there has been a 500 per cent increase in prescription sales of testosterone products for men since 1993.34 Also, much of what has worked for men is apparently being used on women, off-label. Physicians, lacking approved alternatives, have been giving female patients small doses of testosterone products in the hope of boosting desire without side effects. Fingers crossed.

Over the past decade, a number of studies have shown that testosterone may be important for women, especially in terms of staying fit and sexually active. Some studies show that testosterone therapy helps older women, restoring sex drive and sexual fantasies.

Most research has been performed in women who have undergone menopause or have had both ovaries removed (oophorectomy), or who have an underactive pituitary gland (hypopituitarism), because they are already low in important hormones. A number of these studies have been promising. Seemingly, if these women are given testosterone, their mood and sex drive increase. For example, a study in 2006 examined 51 premenopausal women with hypopituitarism. They received testosterone via a patch (300 ìg/day) or placebo for 12 months. Afterwards, the free testosterone levels in those given the testosterone treatment had increased to the normal range, and their mood and sexual function also increased.35

A two-year study found that postmenopausal women receiving a combination of oestradiol and testosterone implants reported significantly greater scores for sexual activity, satisfaction, pleasure, and orgasm compared to women receiving oestradiol alone.36 A 2008 study by Susan Davis and co-sponsored by Proctor & Gamble looked at the effects of testosterone on 814 surgically and naturally postmenopausal women diagnosed with HSDD. They found that a patch delivering 300 ìg testosterone per day increased the number of self-reported sexually satisfying events per month when compared with placebo. The study also demonstrated significant improvement in desire, and sexual function and decrease personal distress in postmenopausal women.37

Health researchers Susan Davis and Esme Nijland suggest that women known to have loss of androgen production—surgically menopausal women, and those with adrenal insufficiency or hypopituitarism—merit consideration for testosterone treatment if they exhibit symptoms of sexual dysfunction.38

Several studies have found that a low testosterone level is not predictive of a diagnosis of low libido, and found no association between low sexual desire and function, and low levels of total testosterone, free testosterone or androstenedione.39 In other words, having a low level of testosterone does not automatically mean a decline in sexual desire or function.

A 2005 study of 1423 Australian women aged 18 to 75 found that there is no single level of any hormone in the blood that separates women who report low sexual function from those who do not. However, women, particularly younger ones, who report low sexual function are more likely to have low levels of the hormone DHEAS.40 DHEA and DHEAS are androgen precursors produced by the adrenal glands. They are converted in the body to testosterone and are the most abundant sex hormones in women.

There is no standard treatment for androgen deficiency in women. The worry is that most testosterone products, even low-dose ones, may contain too much testosterone for the female body to handle. No testosterone product has been government-approved to treat low libido in women in the US, Asia or South America, which has led to the off-label use of testosterone products commonly used by men, but in lower doses. Australian specialists familiar with this area generally recommend treatment with a low-dose 1 per cent testosterone cream (AndroFeme) or a low-dose subcutaneous pellet (off-label). AndroFeme is approved in Western Australia only.

Intrinsa, the skin patch in Susan Davis’ aforementioned 2008 study, is approved in Europe. It is the first treatment for women with low libido to be available on prescription. After being rejected by the regulators in the US, Canada, Australia and Asia, Intrinsa gained approval in Europe in 2006. But not for everyone: it is available on prescription only for postmenopausal women with diagnosed sexual problems, or women who have premature menopause as a result of surgery. It was rejected by the FDA in 2004 not because it wasn’t shown to work—in fact the panel voted 14 to 3 that the manufacturer’s trials showed a meaningful improvement in desire and pleasure—but because data on safety were deemed insufficient.

The downside? Davis’ 2008 study found that the improvement in sexual function was accompanied by 90 per cent more cases of increased hair growth than with placebo, three cases of clitoral enlargement, and two cases of breast cancer in the 267 participants receiving 300ìg testosterone per day. Davis concluded that the long-term effects of testosterone, including effects on the breast, remain uncertain.41

Numerous other testosterone products are being tested on menopausal women. LibiGel, for example—a testosterone gel applied to the upper arm—is in phase III testing at the time of writing. Its manufacturer, BioSante Pharmaceuticals, is hopeful that Libigel will be the first product approved by the FDA for HSDD and anticipate submitting a new drug application in 2012.42

As for side effects, research is pretty limited. Testosterone implants and injections produce extremely high serum levels in women—often 10 times higher than normal levels, even when the hormones are administered in reduced doses. This can lead to side effects such as masculine physical characteristics, deepened voice, hair loss, acne, excessive hairiness and clitoral enlargement. Some of these side effects are irreversible.43 A woman who chooses to have testosterone replacement therapy needs regular breast and pelvic examinations, mammography and evaluation for any abnormal bleeding by a doctor knowledgeable in this area.

As long-term safety data for testosterone therapy are lacking, some health experts advise that it should continue longer than six months only if there has been clear improvement in sexual function and satisfaction and absence of adverse effects.44

Another risk associated with testosterone treatment applied to the skin or in sprays is exposure to others, particularly children and pregnant women. A case was reported in 2010 of a four-year-old boy who was taken to a doctor after an unusual growth spurt and the development of a larger penis and pubic hair. Investigation revealed that for medical reasons his father was taking testosterone gel (50 mg daily) and that, during the past six months, the boy had been sleeping in his parents’ bed.45

Another researcher describes three cases of partially irreversible virilisation of children whose fathers were using testosterone gel. One girl, aged two and a half, had been growing pubic hair for seven months, and had an enlarged (1.5 cm) clitoris and greasy hair; she also exhibited tomboyish behaviour and masturbated frequently. When gel exposure was stopped, it took two months for her clitoris to return to normal size and for masturbation to diminish; 14 months later she still exhibited tomboyish behaviour, and her bone age was two years older than her actual age.46

The FDA implemented label precautions in May 2008, but despite this eight new reports of child exposure were reported in the following six months. Most cases were attributed to patients failing to follow the label instructions and being unaware of the risk. I guess we’re slow learners.

Premenopausal women and testosterone therapy Numerous studies have shown that testosterone therapy

Numerous studies have shown that testosterone therapy has produced improvement in sex drive, arousal and frequency of sexual fantasies in women who are postmenopausal or have had their ovaries removed. However, we know little about the effects of androgen therapy in premenopausal women. There have been very few studies on testosterone therapy for premenopausal women.47 Most studies of testosterone therapy actively exclude premenopausal women from participating owing to the risk of harm to the mother or foetus if pregnancy occurred during treatment.

The oral contraceptive pill, as we know48 may affect androgen levels and decrease our sex drive. So first-line therapy for women experiencing low desire is to ditch the Pill and try a non-hormonal contraceptive such as the intrauterine device (IUD).

One of the American gurus of testosterone research, Jan Shifren, believes that healthy young women with regular menstrual cycles who are not receiving oral oestrogen therapy do not have a biological cause for low androgen concentrations and would not be likely to benefit from testosterone therapy. However, she says that ‘there is interest in the role of androgen therapy for premenopausal women because many young women have sexual dysfunction’.49

And here lies our interest.

Australian researcher Susan Davis believes that because testosterone levels decline in women before menopause and do not appear to change across menopause, women in their late reproductive years are just as likely to have low testosterone levels as women in their early menopausal years.50

Other researchers have proposed that women with low testosterone levels after menopause probably had low testosterone levels before menopause, and that sexual wellbeing before menopause is a good predictor of postmenopausal sexual wellbeing.51

Is testosterone therapy the answer to sexual dysfunction in premenopausal women?

A small trial headed by Rebecca Goldstat showed that premenopausal women treated with testosterone experienced significant improvements in sexual functioning and wellbeing compared to those given a placebo.52

In 2008, Susan Davis and her colleagues found that for premenopausal women aged 35 to 46 years with reduced libido and ‘low’ serum testosterone levels, a daily 90ìL dose of testosterone spray increased the number of sexually satisfying episodes (SSEs) by approximately 0.8 per month. However the study lasted for only 16 weeks and the placebo effect was strong, with women on lower and higher doses reporting the same improvement as those receiving a placebo. No substantial relationships were found between free-testosterone levels and the number of SSEs during the study.53

Davis concludes that testosterone may prove to be a useful therapy for HSDD in premenopausal women, but says further studies are required to prove efficacy and safety.54 Her work in this area continues. As of late 2011 Davis was recruiting premenopausal women aged 35 to 55 for a study to evaluate whether testosterone skin patches are effective in improving sexual interest, arousal and orgasm among women taking SSRI or SNRI antidepressants.55

Contemplating the widespread off-label use by women of testosterone products approved for men and the extensive prescription of testosterone products by doctors, Davis and her colleague Esme Nijland suggested that an uncontrolled clinical trial of the safety of testosterone is already happening in the community.56

Methyltestosterone

Methyltestosterone is a synthetic testosterone derivative. Estratest, a combination of methyltestosterone and esterified oestrogens, has been prescribed for decades to menopausal women with moderate to severe symptoms which did not improve with oestrogen alone. It is also administered to improve sexual desire and response. It is believed that methyltestosterone increases the bioavailable fraction of testosterone by decreasing SHBG levels (SHBG binds to testosterone). Rogiero Lobo and his colleagues found that its addition produced a greater improvement in sexual interest/ desire than oestrogen alone.57

Since Estratest came onto the US market in 1964, over 36 million prescriptions have been filled (1965 to 2003). Estratest followed a number of other testosterone products in the US that were on the market before the FDA brought in its current stringent requirements for demonstrating safety and efficacy. Estratest was made available on the basis that it was equivalent to these earlier products. In 1981 the FDA prompted the manufacturer to apply for formal approval, however 25 years later the FDA had still not approved the application. In April 2003, the FDA concluded that the addition of testosterone to oestrogen products did not provide any greater relief for menopause symptoms. However, Estratest and equivalent generic brands remained on the market.58

In August 2003, a number of lawsuits were launched by people who claimed Solvay had used false and deceptive conduct in its marketing of Estratest. Solvay denied any wrongdoing.59

In August 2006 the National Women’s Health Network petitioned the FDA to stop Solvay from marketing Estratest on the basis of unproven efficacy, known risks associated with oestrogen/testosterone products and other outstanding safety questions.60 The FDA’s rejection of Intrinsa in 2004 was a key lever in the argument against Estratest.61

In May 2008 Solvay and class-action litigants in California agreed to a settlement of $30 million.62 Litigants outside California were awarded $16.5 million two years later.63

In March 2009, Solvay Pharmaceuticals announced it would discontinue supplying pharmacies with Estratest64 and by mid-2010, many other producers of generic esterified oestrogen and methyltestosterone products had also discontinued production.65

Despite the lawsuits and lack of FDA approval, formulations of esterified oestrogens and methyltestosterone are still available off-label and are still being prescribed to menopausal women. Products available in the US include Covaryx, Essian and EEMT.

Tibolone

Not to be confused with Toblerone, tibolone is not a testosterone product but a synthetic steroid which has oestrogenic effects. Branded as Livial, it is prescribed in 90 countries to treat menopausal symptoms and 45 countries to prevent osteoporosis,66 including Australia and the UK. Research has found that tibolone can activate the progesterone and androgen receptors and increase circulating free testosterone.67

In the US tibolone was rejected by the FDA in 2006 after it was found to double the risk of ischaemic stroke in women over 60 years.68 This research also found that tibolone may be associated with a slightly increased risk of endometrial cancer.

Esme Nijland (2008) found that tibolone improved sexual wellbeing in postmenopausal women with low libido. They had greater improvements in desire, arousal, satisfaction and receptiveness than did women receiving transdermal oestrogen-progestin therapy.69

In a review of clinical trials, Margaret Wierman concluded that tibolone is effective in the treatment of menopausal symptoms, vaginal atrophy and improved sexual function for many women but the benefits need to be balanced against the risks.70 Susan Davis and Esme Nijland suggest that postmenopausal women with female sexual dysfunction should try tibolone therapy before trying testosterone with or without oestrogen therapy.71

DHEA therapy

It has been proposed that because dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate, DHEAS, are important precursors for oestrogen and androgen production, treatment with DHEA might help relieve hormone deficiency symptoms in postmenopausal women.

While a number of small studies from 1999 to 2006 indicated benefits from DHEA supplementation,72 experts now challenge the quality of those studies and the claimed benefits of DHEA.

In 2011 Susan Davis and her colleagues summarised the physiology of DHEA in women and reviewed the findings from randomised placebo controlled trials of the effects of DHEA therapy in postmenopausal women.73 They found that while these studies indicated a link between low DHEA levels and impaired sexual function and wellbeing in postmenopausal women, the trials did not show that oral DHEA helped relieve these conditions. They concluded that the trial outcomes did not support the use of DHEA in postmenopausal women.

For women with adrenal insufficiency, Margaret Wierman found that the majority of clinical trials of DHEA replacement showed no benefits for sexual function.74

The DHEA and Wellness (DAWN) study led by Donna Kritz-Silverstein in 2008 found that while DHEA supplementation for healthy older men and women restored youthful DHEA levels and enhanced oestrogens and testosterone in women, there were no benefits for sexual function or mood.75

The DHEA story is a lesson in not jumping to conclusions, especially when research findings are published in the mass media—as they increasingly often are. It often takes a number of high-quality studies to show the efficacy or otherwise of any therapy.

Data emerging from well-designed trials appear to support the benefits of testosterone supplementation for aspects of female sexual function especially for women who have undergone surgical menopause or have hypopituitarism or adrenal insufficiency. Yet this is within the context of industry promotion, and we still do now know the long-term risks of testosterone supplementation. The case is even less clear for premeonpausal women who have been diagnosed with HSDD.

We have to be cautious. As we saw with HRT, the benefits to women were touted well before long-term follow-up was available. There is a risk that testosterone therapy may have a similar storyline—what starts off promising relief may end up delivering sickness in many cases. It’s premature to make a general recommendation about testosterone replacement in older women with low testosterone. As with so much about female sexuality, we just don’t know.

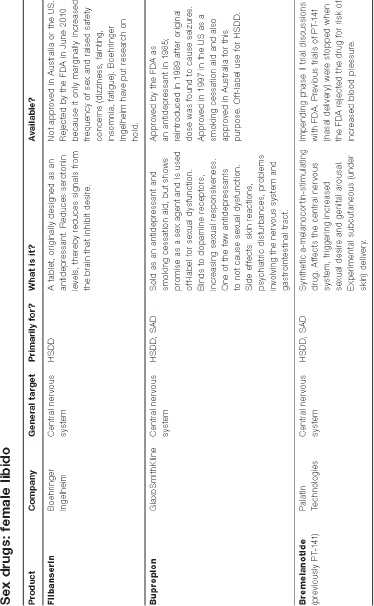

Sex drugs: the central nervous system

There have been numerous failed attempts at gaining approval for drugs that are claimed to alter our brain chemistry and turn us into sexual Stepford Wives. But some companies have been more persistent than others.

Flibanserin

Flibanserin, mentioned in Chapter 6, is the chemical baby of a German drug maker Boehringer Ingelheim (BI). It acts on the central nervous system by hitting several circuits in the brain that are linked to feelings and pleasure. The FDA views drugs that affect the complicated central nervous system with extra caution. Good thing, that.

In the late 1990s, BI found that flibanserin seemed to relieve stress in rats; however, it failed as an antidepressant in human trials. The company surveyed patients in its clinical trial to assess low libido and found that although there were no improvements in mood, many of the women reported a surge in sexual desire and arousal. This resulted in four major clinical trials, involving 5000 women in 220 locations. In other words, a lot of money and a lot of hype.

The effects of the drug were not immediate. BI spokesman Mark R. Vincent said: ‘This is not something that can be taken on a Friday for the weekend . . . There is a gradual increase in sexual desire over a six to eight-week period.’76

The FDA panel agreed that those who took the drug did experience a slight increase in sexually satisfying events, but found that there was no proof that it increased their desire. Further, side effects such as dizziness and nausea and concerns about interactions with other drugs, led the FDA to reject flibanserin in June 2010. Although it’s easy to dismiss flibanserin as a dud, like many drugs, it may resurrect itself in the future. Refashioned, of course.

Bupropion (Zyban)

Bupropion was approved by the FDA as an antidepressant in 1985, and reintroduced in 1989 after the original dose was found to cause seizures. In 1997, the drug was also approved in the US as a smoking cessation aid. It is currently approved in Australia, the US and many other countries as an antidepressant or smoking cessation aid. But it has started to reveal another unexpected benefit: efficacy in treating HSDD in premenopausal women. Doctors now prescribe it off-label for this purpose. Although bupropion has the lowest incidence of sexual adverse effects when used as an antidepressant, its overall record as a prosexual therapeutic agent is less consistent.

Several studies indicate that bupropion relieves sexual dysfunction in people who do not have depression. For example, in a double-blind study, 63 per cent of men and women on a 12-week course of bupropion rated their condition as much improved or very much improved, versus 3 per cent of those taking a placebo.77 In two papers by Robert Segraves and his colleagues, one of which was placebo-controlled, bupropion was shown to improve arousal, orgasm and overall satisfaction in women with HSDD.78 Another study also showed positive effects on orgasmic dysfunction.79

Despite side effects—skin reactions, psychiatric disturbances, problems involving the nervous system and gastrointestinal tract—bupropion, or fine-tuned pharmaceutical like it, shows promise as a future brain drug to ‘improve’ female sexuality.

Bremelanotide

Bremelanotide has the potential to become an international habit. In over 2000 patients who have received its drug, maker Palatin Technologies reports demonstrated reductions of both erectile dysfunction and female sexual dysfunction. Double whammy.

Formerly ‘PT-141’, bremelanotide is a synthetic drug that activates the melanocortin receptors in the central nervous system, triggering increased sexual desire and genital arousal. It began its bizarre life as melanotan II, a sunless ‘tanning’ drug nicknamed ‘the Barbie drug’. Side effects of mild nausea and a ‘stretching and yawning complex’ were accompanied by spontaneous penile erections.

Thinking they were onto something, the researchers did another study on men with erectile dysfunction. They alternated doses of melanotan II with a placebo in ten men: nine of them developed erections when given the real drug. In an interview with CNN in 1999, the study head, Hunter Wessells, said the erections happened effortlessly:

‘These men were not looking at erotic video tapes. They weren’t engaging in sexual activity. They were just sitting around. And on the placebo, none of them got any erectile activity—zero.’80 The researchers concluded that ‘Melanotan II is a potent initiator of erections in men with psychogenic erectile dysfunction and has manageable side effects.’81 This finding was reinforced by another study of 20 men.82

Palatin Technologies developed PT-141, a nasal spray, from melanotan II. It was rejected by the FDA in 2007 after phase II clinical trials showed an unacceptable risk of high blood pressure. In 2008 Palatin backed away from PT-141, but the following year it resumed efforts to get approval for trials of a subcutaneous (under skin) form of the drug. Bremelanotide was born.

In August 2010 Palatin reported positive results for its phase I clinical trial of bremelanotide to treat erectile dysfunction and female sexual dysfunction. The FDA approved further research on the basis that there was no sign the drug caused increased blood pressure. Palatin expected to meet with the FDA to discuss starting a phase II study of the drug both alone and in combination with a PDE-5 inhibitor such as sildenafil (Viagra).

While most of the excitement about bremelanotide has been about spontaneous hard-ons, what might it be able to provide women? A 2004 study by psychologist James Pfaus and his colleagues showed that bremelanotide evoked behaviours in female rats that resembled sexual arousal. Normally in rat sex studies, researchers look for lordosis—when a female rat arches her back in anticipation of the male entering. While subcutaneous injection of bremelanotide did not induce lordosis in the female rats, it did increase solicitation behaviours towards male rats.83 Palatin researchers leapt upon this result.

What is the effect of the drug on human females? A study looked at the effect of bremelanotide on sexual response in 18 premenopausal women with sexual arousal disorder. After a single dose of bremelanotide nasal spray, watching erotic videos did not increase blood flow to their vaginas. However, the women reported increased genital arousal and a statistically significant increase in desire after taking the drug. Also, those who had intercourse within the following 24-hour period were more satisfied with their subjective level of arousal than were those who were given a placebo.84 So maybe we’re not too different from rats after all.

Will a drug like bremelanotide take the hard work out of achieving authentic sexual happiness? Sex writer Leonore Tiefer believes not. ‘Sorry, it’s never going to happen,’ she says. In the meantime, she suggests, there will always be some ‘promising’ new treatment.85

Only four decades ago, the contraceptive pill triggered a sexual revolution, transforming the sex lives of women and men across the world. HRT took this further for women in their post-reproductive years. Men then received the gift of Viagra. Although there is currently no simple pill or patch to safely increase female libido, given the money and effort being expended, it’s probably only a matter of time.

We have entered the age of hormone engineering. The pill, HRT, bioidenticals, testosterone therapy, tibolone . . . We improve these drugs by experimenting on willing trial participants—the ageing and the ill, the menopausal, those suffering from hypopituitarism, the adrenally deficient and those labelled as having hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). When there is enough positive research to prove a drug has benefits that outweigh the risks, government approval is granted. But well before this, a busy trade is already taking place. When drug manufacturers cobble together enough positive research findings to generate excitement, and promote the drug in less stringent countries, an off-label market springs up.

Reflecting a culture that treats symptoms rather than causes, the future will likely see us continuing to take drugs that affect our blood flow, our hormones and our brain chemistry. Many doctors seem to prescribe what their paying patients want. A pill, as they say, for every ill: to boost health and mood, to alleviate pain, to fend off ageing. And, of course, to enhance desire.

Sexual-medicine practitioners and researchers are certainly determined to broaden the range of pharmaceutical treatments available for ‘sexually dysfunctional women’. On the last page of Irwin Goldstein and his team’s epic 760-page textbook Women’s Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment, they share their ultimate goal: ‘We look forward to the future when the biologically focused health-care clinician has more pharmaceutical agents available with high levels of robust evidence supporting their safe and effective use in women with sexual health problems.’86

Spiritual and religious use of drugs has been occurring since the dawn of our species. Some religions are even based on the use of drugs. Perhaps, one day, sex drugs for women will provide a similar pathway to transcendence.

The difference is, we’ll have to pay for it—and it’ll be some pharmaceutical company thanking the gods.