Have you ever been on a team where the talent was strong, but the team wasn’t very good? On the flip side, have you ever been on a team where not every single member was a rock star, but something about the team just worked? We’ve all had these types of experiences. It can be difficult to understand what makes one team successful and another one not. I’ve been fascinated by this phenomenon for many years.

It started for me growing up playing baseball. I played from age 7 until almost 25. I was on some teams where we had remarkable talent, but we didn’t perform well as a team. And I was on some other teams where we didn’t have the best talent, but we performed at an incredibly high level. I found this to be confusing and exciting at the same time. There seemed to be an “X-factor” in the success of my teams. In sports we call this “chemistry.” No one can quite define what that is, but you know when you have it, and you definitely know when you don’t have it. And it’s not just some touchy-feely thing: it actually has a profound impact on how you perform as an individual and as a team. It may be intangible, but as I learned throughout my years as an athlete, team chemistry is one of the most important factors of success in sports.

I erroneously thought this was a phenomenon specific to sports. But after baseball, when I got into the business world, I noticed it there as well. In business we call it “culture.” It’s basically the same thing. It’s that intangible quality that brings people together or pushes them apart; and it makes a huge difference in how we perform individually and collectively. When I realized this, I became somewhat obsessed with it. I wanted to figure out if this was something that occurred just randomly, or if it was something that could be learned, taught, and deliberately created.

It was this obsession, among others, that prompted me to start researching, speaking, and writing about teamwork and culture 17 years ago when I started my business. And being able to bring our whole selves to work is predicated on the environment around us, the people we partner with, and the teams that we build. In this chapter, the fifth and final principle of the book, we’re going to look at the importance of teamwork, at the key components of creating a culture in which people can thrive, and at ways you can influence this with your own team and others with whom you work.

Teamwork Fundamentals

In all my years of being a part of many teams, and in almost two decades of studying, speaking to, and working with teams of all kinds, there are some key lessons I’ve learned, which I often share with the teams I work with, and that I want to address up-front before we dive deeper into this discussion:

We aren’t well trained to work in teams. Most of us didn’t receive much helpful or healthy teamwork training

growing up. Even if we played team sports, as I did, or were involved in other team-oriented activities, our primary training for work came through school. And, what was “teamwork” called when we were in school? Cheating! We were encouraged to do our own work, and we were graded individually on how we performed on tests, papers, and projects. Group projects in school were few and far between, and my experience of doing them was often frustrating because it was hard to get everyone on the same page and make sure they all did their fair share of the work.

After years of education that often discourages teamwork, many of us find ourselves in the business world being told to work within a team. Yet although some organizations encourage teamwork more than others, we still tend to get evaluated, compensated, and promoted as individuals, so the incentive or motivation to work collaboratively can be undercut.

The paradox of teamwork is that for us to fully show up, engage, be successful, and create meaning and fulfillment in our work, collaborating with others is essential; while at the same time, there are forces within us (like our egos, personal ambitions, and fears) and within our teams and organizations (like competition, territorialism, and scarcity), that can spur us to focus primarily on ourselves. It’s important for us to acknowledge this paradox with awareness, ownership, and compassion, and to work through it as best as we can. Teamwork can be challenging, and often involves lots of growth opportunities for us and our colleagues. So the best way to approach it is with a growth mindset, as we discussed in the previous chapter.

Mechanics vs. Psychology (Above the line/Below the line). I heard peak-performance expert Tony Robbins speak many years ago, and it had a big impact on my thinking. Tony states that, in almost every circumstance, “80 percent of success is due to psychology—mindset, beliefs, and emotions—and only 20 percent is due to mechanics—the specific steps needed to accomplish a result.” Through my own experience in sports and business, as well as my research on performance and success, I have found this to be true—on both the individual and the team levels. The challenge is that we spend so much of our time, energy, and attention focused on the mechanics, that we sometimes forget to address the psychology, which diminishes our ability to be successful.

From a team standpoint, I often describe mechanics as “above the line” (what we do and how we do it) and psychology as “below the line” (how we think and feel, our perspective, and the overall morale and culture of the group). Since the below-the-line stuff is 80 percent of our success as a team, we have to pay more attention to these intangible things if we’re going to be the kind of team we want to be.

First Team/Second Team. The idea of asking “What’s my first team?” and “What’s my second team?” was introduced to me through the best-selling book The Five Dysfunctions of a Team by Patrick Lencioni, one of the best books out there on teamwork. This concept is particularly important to managers at every level in an organization. If you’re an individual contributor, your first (and only) team is usually pretty well defined. Most often it includes your peers—the people who report to the same manager as you. You may have a larger team that your intact team rolls up to, but since you don’t really have a second team, your first team is fairly straightforward.

However, when I ask most managers to tell me about their team, they usually talk about their direct reports, or the larger organization that reports up to them if they happen to be a senior leader. This makes sense, especially when we get all the way up to the executive-team level within a company. Most leaders feel a sense of pride, ownership, and commitment to “their team”—since the people who report to them directly or roll up to them are the ones they’re responsible for, are tasked with coaching and developing, and are evaluated themselves in large part based on how they perform.

But leaders, leadership teams, and companies function best when they understand that their “first team” is actually the team they’re a member of, and their “second team” is the team that reports to them. This may seem counterintuitive, because most leaders are going to spend a majority of their time focused on the team they manage. But for things to operate in the healthiest, most effective way, leadership teams should function as actual teams and support one another as peers and fellow members of the same team, not just as a group of managers who have the same boss. This can be tricky, as we’ll get into throughout this chapter, because things can get competitive and priorities can be at odds with our peers, particularly at a senior leadership level. However, understanding that as leaders our peers are our first team and our reports are our second team benefits everyone involved. And any misalignment on a leadership team (especially the higher up in the organization it occurs) creates exponential misalignment in the level or levels below.

The difference between our role and our job. This important distinction was first taught to me by Fred Kofman, Vice President of Leadership and Organizational Development at LinkedIn and author of Conscious Business. When most of us think about our “job,” we think of what we do—engineering, sales, project management, marketing, human resources, operations, design, finance, and so forth. While these descriptions may encapsulate what we do and the title we hold, they’re not actually our job. If we’re part of a team, we each have a specific role, which is what we do, but our job is to help fulfill the goals, mission, and purpose of the company, whatever they may be. In other words, we’re there to do whatever we can to help the team win. The challenge with this is that most of us take pride in our role and we want to do it really well, which is great. However, when we put our role (what we do specifically) over our job (helping the team win), things can get murky—our personal goals become more important to us than the goals of the organization. It takes commitment and courage, but organizations made up of people who understand this simple but important distinction—who realize that everyone on the team has essentially the same job but different roles—have the ability to perform at the highest level and with the most collaborative environment.

There’s an important difference between a championship team and a team of champions. Given my sports background, I’ve always thought of teams who operate and perform at their peak level as “championship teams.” A championship team doesn’t necessarily always win, but they play the game the right way, with passion, and with a commitment to one another as well as to the ultimate result. A championship team is usually greater than the sum of its parts. It’s often chemistry and the below-the-line intangibles that separate the good teams from the great ones. Teams of champions, on the other hand, might have great talent and motivated people, but they’re often more focused on their own individual success. Championship teams know that talent is important, but they focus on the collective success of the team and the highest vision and goals of the group. With leadership teams I make this same distinction in a slightly different way: between a team of leaders (a group of managers who focus on being the best they can be) and a leadership team (a group of leaders who realize that they’re each other’s first team, and that the more unified they are, the more it benefits them, each other, and the people who report to them).

Understanding these five fundamental ideas about teamwork gives us the framework to focus on some of the things we can do to enhance the performance and culture of our teams—regardless of the specific role we play. Our ability to bring our whole selves to work has a lot to do with the environment around us and the team to which we belong. So the more we focus on creating a championship team, the easier it becomes for us to show up fully at work. And the more willing we are to bring all of who we are to work, the more influence we can have on our team. These things are intricately and dynamically linked.

Team Performance

A pioneer in the field of team effectiveness was the late J. Richard Hackman, Professor of Social and Organizational Psychology at Harvard University. Hackman’s research focused on what he called “enabling conditions” that allow teams to thrive. Hackman believed that if you created the right conditions, the success of the team would flow from there. If, however, the conditions weren’t set up in a way to enable success, it didn’t matter how talented the team members were—their success would be limited. I agree with Hackman that conditions are essential to the success of teams. And in my own study and experience of high-performing teams in today’s dynamic business world, I’ve found that there are two important conditions that most effectively enable a culture of engagement, connection, and optimal performance:

Healthy High Expectations: High expectations are essential for people to thrive. But they have to be healthy—meaning there is a high standard of excellence, not an insatiable, unhealthy pressure to be perfect. We almost always get what we expect from others; however, if we expect perfection, everyone falls short and people aren’t set up to succeed. Healthy high expectations are about setting a high bar and challenging people to be their absolute best. This also has to do with being clear, and holding people accountable in an empowering way.

High Level of Nurturance: Nurturance has to do with people feeling cared about and valued—not just for what they do, but for who they are. It also has to do with it being safe to make mistakes, ask for help, speak up, and disagree. In other words, as we discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, this is about people feeling appreciated and their ability to be authentic. Nurturing environments are also filled with a genuine sense of compassion and empathy—people feel cared for and supported.

We often think that in order to have a high bar we can’t also be nurturing. Or we think that if we nurture people, we can’t also expect a lot from them. Actually, the goal for us as team members and leaders, and teams as a whole, is to be able do both at the same time, and to do so passionately. Bringing our whole selves to work, and creating an environment that supports both high expectations and strong nurturing at the same time, takes courage on everyone’s part, and at times goes against conventional wisdom. But being willing to focus on both of these things simultaneously, and encouraging others to do the same, creates the conditions for everyone to thrive.

A great example of this is Hughes Marino, a commercial real estate firm based in San Diego. Jason Hughes, the chairman, CEO, and co-owner of the company, contacted me back in the summer of 2011. He and his team were planning their first firm retreat and he invited me to come and speak.

In our initial phone conversation, Jason said to me, “Mike, I want to support the people on our team to be successful at work and also in life.” I was inspired by his commitment to his team and to their growth and development, both in business and in their personal lives. In talking more to Jason and his wife, Shay—Hughes Marino’s president, COO, and other co-owner—in preparation for their retreat, I found out a few interesting things about their firm and their approach.

First, they represent only tenants. In commercial real estate, which involves the leasing and buying of office space for companies, it can sometimes be challenging and create conflicts when real estate companies end up on both sides of a particular deal, representing the tenant and the building owner simultaneously. In order to eliminate those potential conflicts, Hughes Marino works only for tenants (companies looking to find office space) and not for building owners who are looking to lease or sell.

Second, commercial real estate is a high-stakes, pressure-filled, commission-based business that often creates an internal culture of negative competition and not much collaboration. Jason and his team at Hughes Marino were committed to creating a team-oriented, family-type atmosphere within the firm.

These two things—coupled with their commitment to both personal and professional growth, and the fact that they were including in the retreat all the spouses and significant others of their 15 employees—had me very excited about speaking to all of them about creating a championship team, at work and at home.

The session I delivered at their retreat seemed to resonate with them, and to inspire them to make further commitments to growth and team culture. Over the past seven years, I’ve had a chance to work with the Hughes Marino team on an ongoing basis. They’ve created core values for their firm that include “Embrace the Family Spirit,” “Nurture Your Personal and Professional Life,” and “Be Authentic, Grateful, and Humble.” These values aren’t just nice words for them; they are core beliefs and commitments by which they operate as a company. When you walk into their beautiful office in downtown San Diego, you see on the video screen in the middle of the atrium a scrolling slide show of photos of their team members having fun with their families and doing things that are important to them. In addition to their annual company retreats, they’ve implemented ways for their team members to connect, support one another, learn, grow, share, and embody their core values. They also hold regular events for their clients—some of them they’ve invited me to speak about creating a winning culture and about the importance of appreciation and authenticity.

Their commitment to nurturing their team and building their culture, coupled with their intense focus on excellence and success, has paid off for them in big ways. They now have more than 100 people on their team, with offices in Los Angeles, Orange County, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and Seattle, in addition to their headquarters in San Diego. Their business is growing exponentially. And just like other successful companies with strong cultures that I work with, when you walk into a Hughes Marino office, their commitment to both high expectations and high nurturance is on display physically, in the beautiful design and impeccability of the office space and the personal touch of team-member photos, as well as intangibly, via the energy and attitude of their team. When you talk to their employees, there’s a passion, enthusiasm, and gratitude for being a part of a company like theirs that is infectious. When we’re a part of a team that expects a lot from us in a healthy way, and nurtures us in genuine and generous ways, we can truly thrive—individually and collectively.

Psychological Safety

Google conducted an in-depth research project between 2012 and 2014 aimed at determining the key factors that consistently produce high-performing teams. They called it “Project Aristotle,” and it involved gathering and assessing data from 180 teams across Google, as well as looking at some of the most recent studies in the fields of organizational psychology and team effectiveness. After analyzing the data and research, a number of key findings emerged. According to Project Aristotle, the most significant element of team success is what’s known as psychological safety.

Psychological safety is a concept popularized by researcher and Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson. According to her research, psychological safety is a shared belief that the team is safe for risk taking. People on teams with psychological safety have a sense of confidence that their team will not embarrass, reject, or punish them for speaking up. The team climate is characterized by an atmosphere of interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.

One difference between psychological safety and trust is that psychological safety focuses on a belief about a group norm, while trust focuses on a belief that one person has about another. Another difference is that psychological safety is defined by how group members think they are viewed by others in the group, whereas trust is defined by how one views another. Another way to think about this is that trust is a one-on-one phenomenon, whereas psychological safety is a group phenomenon, so when we’re talking about psychological safety, we’re talking about group trust.

I’ve seen the importance of psychological safety up close for many years with the teams and leaders I coach. When a team creates norms and practices, both explicitly and implicitly, that allow their members to be themselves, speak up, make mistakes, and fail (as we’ve been talking about in different ways throughout the book), they are more likely to collaborate and succeed. All the talent and skill in the world can’t make up for a lack of psychological safety.

According to Edmondson’s research—which was backed up by the findings of Google’s Project Aristotle—there are three things that leaders can do to help create and enhance psychological safety:

At the end of the day, so much of psychological safety comes down to the relationship the leader has with his or her team and each individual member.

Stuart Crabb, former Global Head of Learning at Facebook and co-founder of Oxegen Consulting, told me in an interview, “Progressive organizations realize that the manager trumps the brand, every time. None of the perks matter if your manager sucks.” He continued, “A company should never pay someone extra to be a manager; it incents people to want to lead for the wrong reasons. Focusing on the larger social community is what’s most important.” At Facebook they have set things up organizationally in a way that allows people to advance to a very senior level as individual contributors, so they don’t become managers simply to progress in their careers or make more money.

Leaders have a responsibility to do everything they can to set the tone for the team, build strong and trusting relationships with team members, and create conditions that are conducive to psychological safety. However, championship teams understand that it’s more than just the leader who creates this environment—it’s up to the entire team. Psychological safety is a key element to providing a highly nurturing work environment, which makes it safer for people to speak up, take risks, make mistakes, and ultimately bring all of who they are to work. When this happens, in combination with healthy high expectations, our teams can perform at their best, and so can we as individuals.

Inclusion

Another essential element of creating an environment that is safe, nurturing, and conducive to the success of our teams is inclusion. Inclusion means “having respect for and appreciation of differences in ethnicity, gender, age, national origin, disability, sexual orientation, education, and religion.” It also means “actively involving everyone’s ideas, knowledge, perspectives, approaches, and styles to maximize business success.” The groups and organizations that get the importance of diversity and inclusion understand that it’s not about political correctness, compliance, or public relations; it’s actually about creating the most dynamic, innovative, and supportive working environment for their teams, which allows them to produce the best results.

Katherine Connolly and Boris Groysberg of Harvard Business School conducted a study a few years ago of 24 companies that had earned a reputation for making diversity and inclusion a priority. Some of their key findings were encapsulated by remarks by two executives they interviewed. Brian Moynihan, CEO of Bank of America, said, “When internal diversity and inclusion scores are strong, and employees feel valued, they will serve our customers better, and we’ll be better off as an organization.” Ajay Banga, CEO of MasterCard, said, “My passion for diversity and inclusion comes from the fact that I myself am diverse. There have been a hundred times when I have felt different from other people in the room or in the business. I have a turban and a full beard, and I run a global company—that’s not common.” These executives realize that for their companies to be successful in today’s global economy, creating an inclusive culture is necessary.

In my own research for this book and the interviews I conducted, this topic of inclusion came up on many occasions and in lots of different ways in the context of bringing our whole selves to work.

One of the most fascinating stories I heard was from Jay Allen, the former Chief Administrative Officer at Charles Schwab. Jay told me about coming out as a gay man in the early ’80s at IBM, which was not easy or a common thing to do at that time. Jay said, “In 1983 I was working for IBM in the Bay Area. Only the people who were really close to me at work knew I was gay. It was mostly unspoken.”

But when he applied for and got a promotion, it became a bit of an issue. “It was taking a really long time for my promotion to go through and for me to get officially announced in this new role,” Jay said. “I was told that I needed to meet with Jesse Henderson, the man who would be my new manager, because he had something he wanted to discuss with me. Jesse—a big, African American, ex–football player—was a pretty imposing figure and a man of few words. When we met, he said, ‘I’ve heard a rumor that you’re gay and I want to ask you if that’s true?’

“‘Yes, it’s true, I am gay,’ I responded.

“‘Okay,’ he said, ‘we’ll have to deal with that. It might cause a problem with your security clearance.’”

Apparently in those days, being gay and in the closet was considered a security risk because it was something that could be used for blackmail.

Jay continued, “I said to Jesse, ‘Can I ask you a question? Would you have felt better if I had said no?’

“He seemed a little taken aback by my question, but said, ‘No, I wanted you to tell the truth.’

“I think he did want me to tell the truth, but it seemed to me like he wished the truth was that I was not gay. I’m not sure where this came from in my being, but I then said to him, ‘Look, here’s the deal, you’re black and I’m gay, the difference is everybody can look at you and they know you’re black. But when people look at me, they don’t know if I’m gay. In terms of our ability to do the job, there’s no difference. So this really seems irrelevant and unfair to me.’

“When I said this, Jesse paused and it seemed like there was a little shift in him. He said to me, ‘Well, we’re going to make this work.’

“That was the end of our meeting and that’s what prompted me to officially come out at IBM.”

Jay went on to tell me that Jesse ended up becoming his mentor and one of the most important people in his career. They became very close, and Jesse gave Jay tons of opportunities to grow and advance in his 14 years at IBM. After that he worked for GE and NBC, among others, before ending up at Charles Schwab where he became Executive Vice President of Human Resources and ultimately Chief Administrative Officer, before retiring in 2015.

Hearing Jay’s remarkable story of coming out at work, and a number of others like it, has made me realize that, as sensitive and aware as I try to be about things like this, I have no idea what it would be like to go through that experience myself. It’s yet another example of me recognizing more fully my own privilege.

And although society has made a lot of progress since Jay was at IBM in the early 80s, for people in the LGBTQ community there remain issues and challenges to navigate at work that those of us who aren’t a part of that community don’t have to think about and in many cases don’t understand. When I first started thinking about writing this book a few years ago and Googled “Bring Your Whole Self to Work,” I found information about the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), America’s largest LGBTQ civil rights organization. Since 2002 they have administered an annual report called the Corporate Equality Index (CEI), which looks at how companies cultivate an environment of diversity and inclusion, specifically with respect to members of the LGBTQ community. The HRC also provides resources, support, and guidance for coming out at work. Among other things, they encourage people to “bring their whole selves to work,” and organizations to support their people by cultivating an inclusive environment.

Gender diversity and awareness is another essential aspect of inclusion. When I interviewed Donna Morris, Executive Vice President of Customer and Employee Experience at Adobe, she said something interesting I’d never thought about before. “Bringing your whole self to work as a woman can be a challenge. The more senior you become, the more acutely aware you are of the differences. Most of the female colleagues I know have working partners, while many of our male counterparts have spouses who are at home, so they’re not having to manage and coordinate the same types of things outside of work that many women in their same roles do. That’s a big difference. And while there has definitely been an emergence of stay-at-home dads or partners in recent years, I still think we have a hard time addressing and discussing the additional pressure and challenges women face at work.”

There are many layers of complexity when it comes to gender diversity and inclusion. Talking to Donna made me realize that women continue to face the challenge of opportunity, and even when they do get a seat at the table, there are often different expectations, pressures, and life circumstances that can add to the difficulty. Her insights reminded me of the famous line about Fred Astaire, “Sure he was great, but don’t forget that Ginger Rogers did everything he did . . . backwards and in high heels.”

Issues such as gender, race, sexual orientation, nationality, age, disability, and religion and more can be hard to look at and even harder to talk about, since they touch on things that are both deeply personal and difficult to understand from our various perspectives and worldviews. They also touch on issues of privilege, oppression, bias (both conscious and unconscious), and opportunity. These things bring up a lot of pain, strong emotions, and reactions for many of us, for a variety of reasons.

For people of any minority group—which means just about everyone except straight white males—the reality of the group or groups they belong to can raise issues of pride, challenge, identity, and struggle for them, especially at work. Inclusion is about all of us doing what we can to think about, talk about, and be aware of these issues, and about creating an environment that is as open, understanding, supportive, and as safe as possible—which isn’t easy and can be understandably messy and uncomfortable.

The term covering was coined by sociologist Erving Goffman to describe how even individuals with known stigmatized identities make “a great effort to keep their stigma from looming large.” Kenji Yoshino, a constitutional law professor at NYU, further developed this idea and came up with four different categories in which we “cover”: (1) Appearance, (2) Affiliation, (3) Advocacy, and (4) Association. In essence, we often do what we can to cover aspects of ourselves that we believe might put us out of the “mainstream” of our environment. Yoshino partnered with Christie Smith, Managing Principal of the Deloitte University Leadership Center for Inclusion, to measure the prevalence of covering at work. They distributed a survey to employees in organizations across 10 different industries. The 3,129 respondents included a mix of ages, genders, races/ethnicities, and orientations. They also came from different levels of seniority within their organizations. Sixty-one percent of respondents reported covering at least one of these four categories at work. According to the study, 83 percent of LGBTQ individuals, 79 percent of blacks, 67 percent of women of color, 66 percent of women, and 63 percent of Hispanics cover. While the researchers found that covering occurred more frequently within groups that have been historically underrepresented, they also found that 45 percent of straight white men reported covering as well.

Issues of diversity and inclusion impact all of us. And while they clearly play a significant role in the lives and careers of women and members of every minority group, it’s important that we all be willing to look at and talk about these issues, and do what we can do to create an environment that is as inclusive as possible. For us to do this, it takes everything we’ve been discussing in this book—authenticity, appreciation, emotional intelligence, growth mindset, teamwork, and the rest. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the paradox of being human is that on the one hand we’re all unique—by virtue of how we look, our background, how we think, our skills, our personalities, what we value, our histories, and so forth—yet on the other hand, the further down below the waterline we go on our iceberg, the more we’re alike. We’re all human beings and we experience the same emotions—love, fear, joy, shame, gratitude, sadness, excitement, anger, and more.

I was reminded of this specifically on a trip to India last year to speak to the leaders and employees at the Bangalore office of my client Nutanix, a cloud-computing software company based in San Jose, California. It was my first trip to India, and I was blown away by the beauty and passion of the people, the vibrancy of the culture, and the energy of Bangalore and the country as a whole. I was also made keenly aware, as I often am when I travel outside of the United States, of my own privilege and how my cultural background shapes (and in many cases limits) how I see the world. It was both humbling and eye-opening—definitely a growth opportunity. And at the same time, as the Nutanix employees and I did the “If You Really Knew Me” exercise together, I found that many of the things that were below the waterlines on the icebergs of the people in India were similar to what’s below the waterline on my own iceberg and that of many of the people I know and work with in the U.S. In other words, we’re way more alike than different. Being able to understand and appreciate the paradox of our differences and commonalities is fundamental to creating a culture of inclusion. And this type of inclusive environment is foundational to being a championship team and encouraging people to bring all of who they are to work.

Celebration and Fun

At the Wisdom 2.0 conference in February 2015, when I was on that panel with Dr. Michael Gervais and George Mumford about peak performance, Michael said something else about teamwork that fascinated me. It was just a few weeks after the Seattle Seahawks lost the Super Bowl to the New England Patriots in dramatic fashion. The Seahawks had won the Super Bowl the previous year and were marching down the field to score what looked like the go-ahead touchdown to win back-to-back championships. Unfortunately for Seattle, it didn’t turn out that way, as they threw an interception at the goal line just before the clock ran out, and New England hung on to win the game.

Since Michael works closely with Pete Carroll and the Seahawks, he was asked about the Super Bowl loss and how he and the team reacted. “It was awful,” he said. “In the locker room after the game we were all stunned and upset. I could see every stage of grief displayed right in front of me. Some guys were angry, some were in denial, others were in tears, it was devastating to lose, and to lose the way we lost, when it looked and felt like we were about to win. But I’m a psychologist, so in addition to my own feelings about the game and the outcome, I started to think about what was happening for all of us—the players, the staff, and the fans who were rooting for the Seahawks to win. There’s a difference between loss and actual grief. Nobody died. We lost a game. Yes, it was a big game, but it was just a game. What I realized in that moment was that what we’d actually lost, more than the game, was the ability to celebrate with one another. If the team had scored that final touchdown and we’d won the game, we would’ve been screaming, hugging, highfiving, and celebrating passionately with each other in that locker room, and so would’ve all the fans who were rooting for the Seahawks.”

Michael’s insight was powerful and poignant. Oftentimes, what we want as much as or more than the accomplishment itself is the permission to celebrate with the important people around us. In our obsession with performance and achievement, we sometimes forget to celebrate along the way, which is essential. Why do we have to wait to win the Super Bowl to allow ourselves the joy of celebration? As a former athlete and lifelong sports fan, I enjoy following the games, teams, and seasons. And as someone who is passionate about teamwork and culture, I find that sports teams are often great case studies in these things. But one of the many differences between sports and business is that in most businesses there’s no “championship” at the end of the year—so there aren’t always big, built-in collective goals that can focus our attention and effort over a finite amount of time. Because of this, business teams have to create reasons and opportunities to celebrate together and to have fun.

At most of the company conferences and offsites where I speak, I can tell that one of the most valuable things about these events for the people who attend them is the opportunity to come together, spend time with one another outside the office, and have some fun with each other. Conversing over dinner, telling funny stories at the bar, or taking goofy photos during an adventure or teambuilding activity end up being what people enjoy and remember the most from these events. And making things fun on a daily basis in the office is also something championship teams do. In 301 Ways to Have Fun at Work, Leslie Yerkes and Dave Hemsath write that “organizations that integrate fun into work have lower levels of absenteeism, greater job satisfaction, increased productivity and less downtime.”

Creating a positive and fun environment can attract people to our team or company. In a Forbes article titled “The Benefits of Fun in the Workplace,” Kathy Oden-Hall, Chief Marketing Officer of Paycom, an online payroll- and human-resource-technology provider, stated that “60 percent of 2015 college graduates reported that they would rather work for a company with a ‘positive social atmosphere’ even if it meant a lower paycheck.”

Matthew Luhn knows a thing or two about working in fun and creative environments. He worked on the story team at Pixar Animation Studios for more than 20 years. His story credits include Toy Story, Finding Nemo, Up, Monsters Inc., Cars, and many others. He began his career at the age of 19 as the youngest animator on The Simpsons TV series. Growing up, he worked for his family’s business—a chain of toy stores in the San Francisco Bay Area called Jeffrey’s Toys, owned and operated by his parents, as his grandparents before them, and his great-grandparents before them.

When I interviewed Matthew, he told me, “I learned a lot working on The Simpsons early in my career, and, of course, being at Pixar for over twenty years. In those environments they didn’t set out to create a ‘creative culture’ per se; they just allowed us to be ourselves, have fun, and create—without too much pressure or stress. Hierarchy kills creativity.” Matthew continued, “I think some of the things that my dad taught me as a kid are the key elements in allowing fun and creativity to flow organically in business.”

Celebration and fun are essential to creating a positive environment and culture, which help us engage more in our work, connect more to one another, and tap into our creativity. Championship teams know this and do what they can to both directly and indirectly concentrate on these important aspects of teamwork.

The Golden State Warriors have had an incredible run of success over the past few years, winning NBA titles in 2015 and 2017, and setting a record for most wins in a season in 2016. Their head coach, Steve Kerr, has four core values that he, his coaching staff, the team, and the entire organization focus on: joy, mindfulness, compassion, and competition. I’m a lifelong Warriors fan, having grown up in Oakland (where the Warriors play). For most of my life, they were one of the worst teams in the NBA, so to see them having this kind of success is really fun. What’s even more exciting to me, however, is the way they play. They really do embody those four values, and I love that joy is the first one, because if you watch the Warriors, they do play the game of basketball with joy. And the fun they have on the court, on the bench, and with each other is not only inspiring to watch, it’s also an incredible example of a championship team in action.

Competition

Let’s talk about another one of Steve Kerr’s four core values: competition. As a former athlete, and as someone who worked in sales and has quite a strong competitive spirit, I know a few things about competition. I’ve also studied it and seen it play out in both healthy and unhealthy ways within teams and companies for many years. Competition is part of life, and especially of business. It can be harnessed in a productive way for teams, but it can also be incredibly damaging and detrimental to the culture of a team or company. So, it’s important to understand that there are two types of competition: negative and positive.

Negative competition is when we compete with others in such a way that we want to win at the expense of the other person or people involved. In other words, our success is predicated on their failure. Negative competition is a zero-sum game, and is based on the adolescent notion that if we win we’re “good” and if we lose we’re “bad.” It’s all about being better than or feeling inferior to others—based on outcomes or accomplishments. In a team setting, negative internal competition shuts down trust and psychological safety, and negatively impacts the culture. It usually takes one of three forms:

Positive competition is when we compete with others in a way that brings out the best in us and everyone involved. It’s about challenging ourselves, pushing those around us, and allowing our commitment and skill, and the motivation of others, to bring the best out of us and tap into our potential. When we compete in a positive way, it benefits us and anyone else involved. Of course, we may “win” or we may “lose” the competition we’re engaged in, and there are times when the outcome has a significant impact and is important. But when we compete in this positive way, we aren’t rooting for others to fail or obsessed with winning at all costs, and we realize that we aren’t “good” or “bad” and that our value as human beings isn’t determined by the result. Positive competition is about growth, grit, and taking ourselves and our team to the next level.

A very simple example of this comes from exercise. Working out with another person is a positive, practical strategy for getting in shape, because having a workout partner creates accountability, support, and motivation. Let’s say you and I decided to work out together on a regular basis, and we picked a few different activities such as running, biking, and tennis that we’d do a few times a week. And let’s imagine we decided to add a little competition to make it more interesting. If we competed against each other in a negative way, I would be obsessed with figuring out how to run faster, bike farther, and beat you at tennis. And if I got really into it, I might find myself feeling stressed before we worked out, and after we got done I’d be either happy or upset depending on how I did in comparison to you on a particular day. I might even find myself taunting you if I “won,” or feeling defensive, jealous, or angry if I “lost.”

However, if we went about these same activities in a positively competitive way, we could still compete to win in tennis or race each other in running or biking. We wouldn’t waste our time and energy attaching too much meaning to the outcome, but instead would realize that by pushing one another past our perceived limitations we would both get a better workout, helping each of us to be as healthy and fit as possible

In a team environment, it’s important to pay attention to competition. We all have the capacity for both negative and positive competition. The more aware we are of our own and others’ competitive tendencies, the more easily we can talk about and pay attention to them when they manifest themselves. Championship teams embrace competition, and harness its positive power to fuel individual and collective growth and success. And creating a culture of positive competition can bring out the best in us and everyone on the team.

The Impact of Culture

Chip Conley, founder and former CEO of Joie de Vivre Hospitality and current Strategic Advisor for Hospitality and Leadership at Airbnb, is a business and thought leader who is passionate about company culture. In addition to having started Joie de Vivre at age 26 in 1986, and then making it very successful over the next 24 years with himself as the CEO (before selling it in 2010), Chip is the author of a number of best-selling books, among them Peak: How Great Companies Get Their Mojo from Maslow, which shows how legendary psychologist Abraham Maslow’s ideas helped his company, and can help other companies as well, to operate at peak level. When I interviewed Chip on my podcast, he told me, “Culture and customer service, especially in the hospitality industry, are one and the same. If you don’t have a strong culture, you’re not going to have a reputation for service.” His interest in and passion for building a strong culture in his company came early.

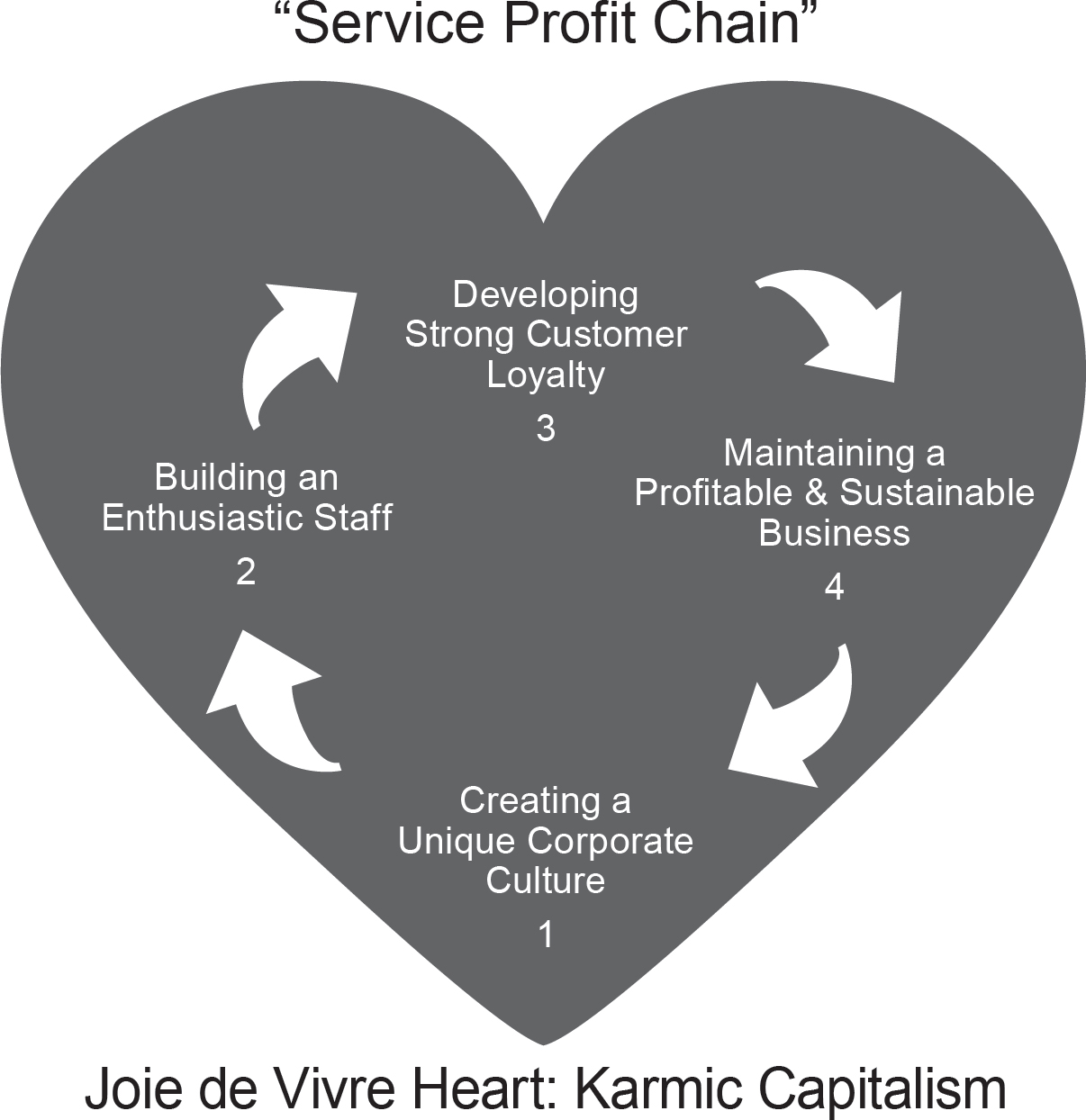

Chip went on: “There was a book from the 1980s called The Service Profit Chain, written by three Harvard Business School professors: James Heskett, Earl Sasser, and Leonard Schlesinger. They were able to show empirically that companies with a strong culture create happier employees, which creates happier and more loyal customers, which creates market-share growth, which creates more profitability, which creates happier investors who are more willing to invest in the culture, so it becomes a virtuous cycle.” The book had a profound impact on how Chip thought about culture and business. In naming his company Joie de Vivre, which means “enjoyment of life” in French, he created both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge was that people couldn’t spell or pronounce it, and didn’t know what it meant. The opportunity, however, was that it was the company’s name and its mission all in one, which made it easy for his employees, customers, and investors to understand once they got it.

“We created something called the ‘Joie de Vivre heart,’” Chip continued. “Just imagine a visual icon of a heart with four points on it. At the base of the heart was ‘Culture,’ and if you did that well, there was an artery on the heart that pumped blood to the second point, which was ‘Happy Employees.’ Point three on the heart had an artery to it, which was ‘Loyal Customers.’ And point four was ‘A Profitable and Sustainable Business.’ So, we could teach our employees, 60 percent of whom spoke English as a second language, about our mission and our culture in their first week on the job. The visual image of a heart is universal and it transcended language. We empowered people to speak up if one of the arteries in the heart was not working well.”

Chip said that one of the things they had to do as they grew, especially once they got past 1,000 employees, was to “democratize culture.” He said, “We created cultural ambassadors for all fifty-two of our hotels. The ambassador took on this role, in addition to their regular job, and it couldn’t be the general manager—it had to be a mid-level manager or a line-level employee. They were elected by their fellow employees and would be in the role for a year. There were three primary focuses for each of these cultural ambassadors. First, was to figure out how they could grow and evolve the culture of their particular property. They would work with the GM and the head of HR at the hotel to come up with creative ways of doing this that resonated with that site and their unique team. Second, they worked to develop and evolve the recognition program so that it stayed fresh and motivating for everyone. And third, they focused on philanthropic activities that allowed the employees to connect with and contribute directly to the community.”

Chip shared an example of such initiatives—an idea that came from one of their cultural ambassadors. “During a downturn in the economy, we were trying to find creative and inexpensive ways to recognize our employees. One of our cultural ambassadors had the idea of inviting one of their regular guests who was currently staying at the hotel to come to their monthly staff meeting and talk for ten minutes about what they enjoy about being there. They asked the guest beforehand if they would call out at least three specific people and publicly recognize them at the meeting. It ended up being a simple but powerful way for us to show recognition to our employees and connect with our most loyal customers. And it didn’t cost us anything. We were able to share this idea that came from one of our cultural ambassadors, and scale it to the entire company.”

Chip ended our discussion about the importance of culture by saying, “Culture is the ultimate strategic differentiator for a company. My favorite line about culture is, ‘It’s what happens around here when the boss is not around.’ Culture is really the personality of an organization.” The investment Chip and his team made in their culture paid off in many ways. Joie de Vivre became the second largest boutique hotel company in the United States. By making a commitment to culture as their foundation, they were able to create happy employees and loyal customers, which led to a profitable and sustainable business.

Championship Team in Action

Another great example of how teamwork and culture impact results in a significant way is the San Francisco Giants. Over the last eight years I’ve been honored to have been invited several times to speak to their front-office staff, as well as to some of their players and coaches during spring training. I first partnered with the Giants in the spring of 2010. They had a young team that year, and some talented prospects in their minor league system, so the future looked bright. It seemed like they were a year or two away from being really good, and also like they were starting to develop some real chemistry as a team and as an organization.

They ended up making it into the playoffs on the final day of the 2010 season, but all the experts said they didn’t have enough talent to win the World Series. They ended up getting hot that October, playing incredibly well in the playoffs, proving the experts wrong, and winning the World Series for the first time since the team had moved from New York to San Francisco in the late 1950s. It was a huge deal for the entire Bay Area and for Giants fans everywhere. Just as Michael Gervais talked about, it gave everyone permission to celebrate—and we did, big-time.

The Giants ended up winning three World Series championships—in 2010, 2012, and 2014—during a five-season stretch. And not only was that incredibly difficult in itself—they did it as underdogs in just about every post-season matchup they were in during those championship runs. They had good talent, but in most cases they didn’t look like the best team on paper. Their ability to play well in big games, fueled by their incredible team culture, is what propelled them to those World Series titles.

They seemed to understand and embody all the essential intangible qualities—that below-the-line stuff that truly drives success and performance. Two particular examples epitomize to me both the success of the Giants during their championship run, and what it means to care about each other and know that they’re all in it together.

On the Friday night of the final home series of the season, the Giants give out an internal award called the “Willie Mac Award.” It’s named after Hall of Famer Willie McCovey, who played for the Giants his entire career, from 1959 to 1980. It’s voted on by the team and coaching staff, and is given to the most inspirational player each year. In 2013 the award went to Giants right fielder Hunter Pence. Hunter was an All-Star player who the Giants picked up at the trade deadline the season before. He became the team’s inspirational leader in the playoffs in 2012, and his energy and enthusiasm in the clubhouse and dugout, as well as his play on the field, helped lead them to their second championship in three years that previous season. He played really well in 2013, but the team was, unfortunately, not going to the playoffs that year.

I was at the ballpark for that last Friday night home game of the 2013 season, and was excited to see the announcement of the Willie Mac Award, which is always a big deal and a fun ceremony. I was fired up when they announced that it was Hunter Pence, who seemed quite deserving of the award, and I also looked forward to hearing him speak, since he’s such a passionate guy. Upon being announced as the winner right before the game, he came out onto the field surrounded by past winners of the award, and stood next to Willie McCovey himself, who was in a wheelchair beside the podium. Hunter got to the microphone, thanked Willie and others for the award, and then said something directly to his teammates that I wasn’t prepared for: “I love every minute with you guys. I tell you that every day. I know some of you get uncomfortable when I tell you that I love you. You think it’s soft. But I actually think it’s the strongest thing we’ve got.”

I was deeply moved by Hunter’s courageous and vulnerable expression of love for his teammates. Telling them he loved them in front of 42,000 fans (let alone the multitudes watching it on TV), and the fact that he underscored it by saying that love is the strongest thing they had together, made my heart sing on so many different levels.

Fast forward to the next season (2014): The Giants are back in the World Series, it’s game seven, and they’re on the road against the Kansas City Royals. With two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning, they’re up by one run, but the Royals have the tying run on third base. Giants pitcher Madison Bumgarner gets Royals catcher Salvador Pérez to hit a pop-up into foul ground. Giants third baseman Pablo Sandoval catches it for the third and final out of the game, and they win their third World Series title in five years. As Buster Posey, the Giants’ All-Star catcher, comes out to the mound to give Bumgarner a celebratory hug, these two big, strong, tough men from the South—Georgia and North Carolina respectively—embrace each other. And right before the rest of the team comes piling out of the dugout to jump on top of them, you can see Bumgarner lean over and say into Posey’s ear, “I love you!” It was one of the most heartwarming things I’ve ever seen on a baseball field. It moved me to tears and epitomized what a championship team is all about—caring about each other, knowing that they’re all in it together, and, ultimately, loving one another.

Creating a championship team takes commitment, courage, and faith. We have to be willing to put our egos, agendas, and personal ambitions aside, at least to some degree, so that we can focus on the bigger goal and vision. A great team epitomizes what we mean by the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. With our work teams, this is about being all in, having each other’s backs, and being willing to work through issues, challenges, and conflicts together. It’s also about making a commitment to care about each other as human beings. This isn’t always easy to do, but it’s necessary if we’re going to create the kind of success and fulfillment we want. And when we do this, we become part of something bigger than ourselves, and we give meaning and purpose to the work that we do and to our lives—which is what bringing our whole selves to work is truly all about.