CHAPTER 8

Move More and “Exercise” Less

Lack of activity destroys the good condition of every human being, while movement and methodical physical exercise save it and preserve it.

—PLATO

Don’t exercise beyond the limit of your brain’s ability to control a movement properly.

—DAVID WEINSTOCK, physical therapist and author

MYTH: You should stretch thoroughly before a workout.

FACT: This is not advised. Simply jog gently to melt the “fuzz” in the fascia; swing the arms and skip a little to open up the range of motion.

In this chapter, I’m going to suggest that you don’t need to “exercise” at all.

Since the invention of the yardstick and the stopwatch, we have been quantifying movement. The government releases important-sounding guidelines on the minimum number of minutes of daily exercise. People rush to their gyms and dutifully perform their routines, while GPS devices track their movements and social media hails their hero workouts.

Most of us who become committed to a workout regimen subscribe to the popular acronym FIT—frequency, intensity, and time. But often our exercise is too vigorous, at the same time that it doesn’t address the damage caused by parking ourselves in a chair for the rest of the day. Even if we run for 30 minutes, what about the 930 other minutes of daily nonsleep time?

Modern humans share with zoo animals the diseases of captivity. We exercise to compensate for restricted habitat and range. And we regard exercise as we do nutritional supplements. Just as supplements shouldn’t be the foundation of our diet, exercise routines shouldn’t form the bulk of our daily movement.

INVISIBLE TRAINING

We have sidelined movement from our daily routines. For physical health alone, if you simply move through a wide range of motions throughout the day, “exercise” becomes redundant. Our bodies are meant to be used, and movement is what they are adapted for. Exercise is great. But the only genuine, healthful, and sustainable reason to exercise is because you love it.

In medical school, I was taught anatomy and the configuration of the human body—a static human body. And as a doctor in the clinic, I “examined” patients who were sitting passively on a table, without assessing their movement. Only later would I begin to understand the fluid mechanics and marvelous interconnectedness of a body in motion.

When I’m asked, “What is the best position or movement?” I respond by saying, “Your next one.” If you have remained in any single position for more than twenty minutes, change it up. As you do, expand the ways you reposition your tissues and load your joints. Each time you stress and move new areas, local blood circulation increases. Mix up the ways in which you interact with the environment—just as our ancestors did constantly.

Running alone isn’t enough to get you to a state of excellent health. In addition to running, we need to engage in a variety of activities and movements. Walking, lifting objects (properly), gardening, squatting, crawling, climbing stairs—all of these “supplemental movements” should be done briskly and with graceful ease, and at frequent intervals throughout the day. In other words, apply the level of attention that you bring to your running form to all of your movements, and regard yourself as in a constant state of “invisible training.”

The “isolation training” that many people do in gyms often consists of programs for narrow, specific purposes, and isn’t always healthful. Instead, by teaching the body to link its movements and become one machine, not a Frankenstein-like assemblage of parts, you will be far more suited to many functional and athletic tasks.

A STANDING ORDER

For a moment, let’s tag back to the most damaging habit that we’ve subjected our bodies to: chronic sitting. As we discussed in chapter 2, sitting is associated with a number of physical problems and chronic ailments, and prolonged sitting increases the likelihood of an earlier death. Consider plane flights: typically, we drive (in a sitting position) to the airport, cram ourselves into an airplane’s economy seat, then again drive (while sitting) to our destination, in order to sit at a meeting or sit around with friends. It surprises me to see people without roller bags in airport terminals congregate at the base of the escalators, when the wonderful opportunity of stairs—which are generally faster—waits nearby, unused. We should all be taking every opportunity to move.

After hours in a chair, our muscles and fascia essentially reprogram themselves, misaligning our entire kinetic chain. Hips tighten, hip flexors shorten, and the gluteus maximus gets “remodeled,” such that we lose the optimal tension, spring, and range of motion that is needed for efficient walking and running.

In what some researchers have termed the “active couch potato” phenomenon, the negative effects of prolonged sitting may cancel out the gains accrued from exercise, even when the exercise includes training for a marathon or half marathon. (Emerging research that traces the roles of inflammatory- and fat-regulating enzymes, such as LPL1, also supports this.) Runners and others who train vigorously may be at higher risk: they tend to be professionals, confined to long hours at a desk or in a car. They may rationalize, however subconsciously—but incorrectly—that their extraordinary exercise efforts more than compensate for any risks from a mostly sedentary life.

Prolonged muscular inactivity, as experienced on long plane rides, can also place someone at risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or blood clots. A flight from New York to Germany entails less sitting than an eight-hour workday at a desk. We may need to start seriously examining the health effects of our ubiquitous sedentary daily lives.

A stand-up desk is a partial antidote to sitting, and I have used one for over ten years. The desk holds my laptop, phone, and papers, and I keep a stool beside it to elevate a foot to change position while I read and type. At home, I rarely sit in chairs, and take every opportunity to sit on the floor and change up my position, as if in a yoga class. We can all do this. Visualize yourself as an ancestral human—unassisted and unconstrained by chairs and tables—versus the modern zoo human.

THE SPICE OF LIFE

Our neuromuscular systems are adaptive and trainable. They enable us to react to, temper, dissipate, redirect, and stabilize large forces. Nerves control muscles (what’s meant by “neuromuscular”), and the more we practice and build proprioception and balance, the more neuromuscular control occurs locally—reflexively, automatically—without the intermediate step of engaging the thinking brain.

Fascia plays a role with this (see chapter 5), because it relays signals about when to tighten, loosen, or stabilize, without us needing to cogitate on it. Proprioceptors and mechanoreceptors in our feet and throughout the body sense load, pressure, and blood flow. To some degree, all of this movement and countermovement trickles down to individual cells, and may even affect which genes get turned on and off. Gene expression, we’re learning, is a product of what we do, not just who we are.

When you’re walking or running, proprioceptive mechanoreceptors, which generally sit at the nerve endings, send signals to the cells of the muscles in the feet and legs. The cells (which are mostly water) behave like a sponge, and are refreshed by constant filling and squeezing, in just the right amounts. Disuse of the mechanoreceptors (as occurs in prolonged bed confinement) can result in a pressure sore or bedsore. Fluid accumulates in the ankles. The sponge is wrung out or overfilled, and isn’t refilling properly. Simply changing up one’s position helps move lymph and fluids and blood through the tissues.

YOU GOT TO MOVE IT…MOVE IT!

So, if you’ve been on the couch or at a desk for years and want to expand your range of motion, where do you begin? Just move, and you will improve. Bend. Compress. Twist. Pull. Push. Lift. Squat throughout the day, whenever you can. I squat to rub my dog’s belly—it’s as good for me as it is for her. One hundred squat-jumps in the gym aren’t required.

Undertake all of this movement within a safe range of motion. Remember that the body adapts gradually. Never make a sudden or outsized change to your routine or movement patterns (or to your footwear).

The perfect, most accessible movement is walking. It helps us in every way—mechanically, metabolically, psychologically. If you walk outside, all of your senses are stimulated. I am one of few physicians who still does traditional walking rounds: I walk from room to room visiting patients, instead of “rounding” at a circular table with laptops. (“Rounds” originated at the original Johns Hopkins Hospital, where the halls of the ward were configured in a large circle.)

Physical therapist Gary Gray coined a term for the motor control that we need in order to prevent injury and excel in sports: mostability, a blending of mobility and stability. It describes the ability to take advantage of just the right motion, at just the right time, at just the right speed, in just the right plane, and in just the right direction. The objective is to elongate the muscles and move the joints through their full range of motion, while using skillful motor control to manage the forces that are generated.

By contrast, instability can be referred to as any degree of mobility that isn’t fully controlled.

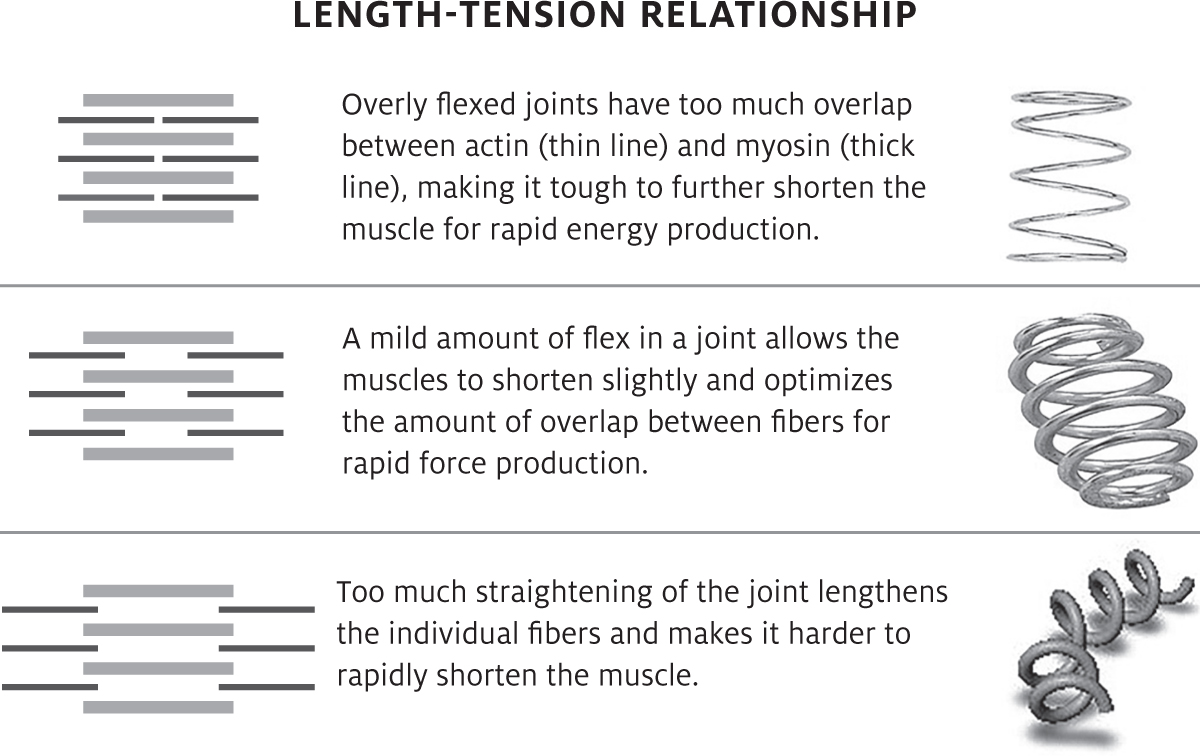

Core instability, exacerbated by fatigue, causes the right knee to dive in and left hip to drop, leading to decreased motor control and efficiency—like a tired spring.

TO STRETCH OR NOT TO STRETCH? THAT IS THE QUESTION.

There’s been a lot of discussion about whether one should stretch before running. The current consensus is that it’s not necessary, and may even be counterproductive.

Some of the confusion arises because stretching can refer to a variety of routines and movements. In static stretching, a specific position is held for ten or more seconds, as in many types of yoga, and can be harmful if done prior to running. In active isolated stretching, on the other hand, a muscle is contracted and held only for a moment—at most a few seconds—and then is lengthened. Repeated several times, this kind of stretching can release neurologic inhibition in the muscles and fascia. (This inhibition, which may feel like tightness, can indicate that your nervous system is preventing a joint from moving fully—and may be protecting it from injury.)

Active isolated stretching can open you up to a wider range of motion, though it may help only modestly. The goal is to loosen, not stretch, and the best way to do this is to simply run at an easy, relaxed pace. At the start of a run, swing the arms and skip a little to open up the range of motion, then start out jogging slowly to melt the “fuzz” in the fascia. As your body warms up, your mobility and range of motion will expand naturally. Add a few skips, lunges, and even a few short pickups (ten-second sprints), in which you lengthen your stride and test your full range of motion. This is dynamic stretching—and is done mostly when you’re warmed up.

Indeed, simply keeping your body limber, supple, and active throughout the day is more important than a dedicated program of stretching, or a rigorous menu of positions, yoga poses, and movements. Especially now that we are learning of the increased risk of mortality—early death—from the benign-sounding activity known as chronic sitting, we should pay special attention to daily movement.

Remember the tensegrity principle. The body wants to remain in a balanced state between tension and compression. Thus stretching needs to be viewed in the context of what, exactly, needs stretching.

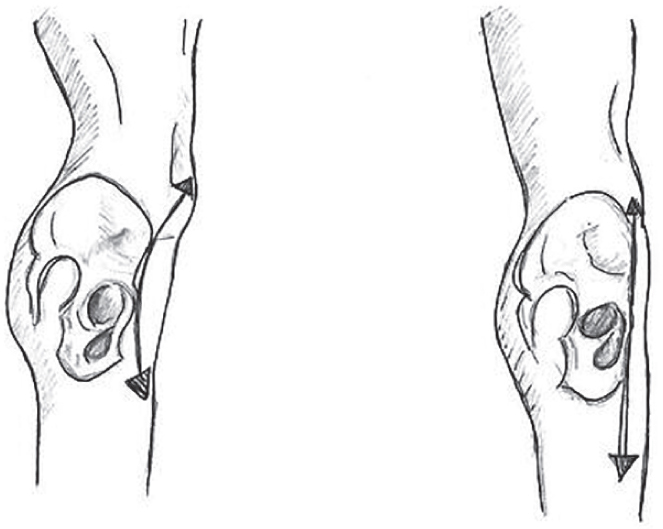

Commonly, I see tightness in the anterior hips, or hip flexors. Think of your pelvis and femur secured into a “comma” position, caused by shortened hip flexors that accompany long periods of sitting. (Your frame should be erect, with a flat, neutral pelvis when you stand upright, as in the illustration that follows.) Now combine that comma position with a tight and sore upper hamstring. One might think that stretching the hamstring is a priority, but this will only exaggerate the curve in the “comma” and result in more imbalance and compensation.

The “comma,” or tilted pelvis, at left, is an artifact of prolonged sitting—compared to a flat, neutral pelvis, at right.

Ron Clarke, who set seventeen world records, said that he never stretched before running. Yet to watch Ron run was to watch stretching in action. He ran with perfect balance and a full range of motion. You can see (this page) that his stride angle (the angle of separation between his thighs) is greater than 90 degrees.

Ron retired from distance running in his prime, at age thirty-three. Meb Keflezighi qualified for the Olympics for the fourth time at age forty. Like Ron, Meb didn’t do stretching and mobility work when he was younger. Now, however, he does an extensive series of drills similar to the ones I prescribe, in order to maintain balance and range of motion. He does them all in a dynamic and relaxed way, never pulling hard on his muscles.

Ron Clarke (#2) in full flight

Similarly, you don’t want to take your exercise into the exhaustion zone, as your muscles will tighten up on you. I want the final mile of every run to be the most fluid and relaxed of all, with the fullest motion and longest stride. This applies to walking, too. No need for long post-workout stretching sessions. You just stretched, while in motion.

It’s simple: after you have worked out comfortably—avoiding exhaustion and cooling down slowly—you are set up for optimal recovery. No need to do anything more. But remember: if you return to the chair immediately after a workout, you’ll sabotage the range of motion that just nourished your body. Your muscles and joints and fascia will cool down and “set” in that sitting position, and you’ll have to start over the next day. This is similar to spending good time and money on massage or deep tissue work to alleviate positional pain and tightness—then immediately resuming the damaging posture that necessitated the treatment. I witness this daily.

MINIMALIST GOLF? (NO, NOT MINIATURE GOLF.)

Many runners are also golfers, and golf qualifies as a type of full body movement—when done “old school.” One of my mentors, Dr. Phil Maffetone, wrote a book called The Healthy Golfer, which doesn’t prescribe the best grip for your club nor demonstrate the correct swing plane. Instead, it shows you how to lower your score by becoming the healthy, flexible, focused, and relaxed person that the sport demands. As with running, a good golf game requires listening to and caring for your body. Maffetone starts by encouraging golfers to wear shoes with flat, flexible, spikeless soles, and to go barefoot during the day and eat the right foods.

Part of my early aerobic base for running was built on golf. During the summers, beginning at age eleven, I walked eighteen (or more) holes of golf each day with my brothers at our local course. Our golf shoes were Keds and Converse sneakers, and the bag I carried weighed almost as much as I did. We couldn’t afford to lose golf balls, and routinely climbed across rocky terrain and forded creeks to retrieve them. We never took lessons, and played with blade clubs—old wooden and steel clubs with tiny sweet spots. As a result, we developed natural swings. Now golfers rely on oversized titanium clubs like the Big Bertha driver, and often don’t get the full feel of the ball and club.

My wife, Roberta, and I continue to play, and when in Colorado we found a little-known course called Perry Park that is tucked into the red rocks of Colorado. Walking is encouraged there, and we were allowed to bring our dog. Eighteen holes took us three hours, and we finished more refreshed than when we set out. The grounds crew even allowed us to go on morning runs.

Later, we experienced golf at its purest on a trip to Ireland. The terrain was impassable for a cart, and the elderly caddies were the healthiest and strongest seniors I have met. Most courses in the United States now require that golfers ride carts. Walking is prohibited! I tried a cart once, and found that in addition to feeling lethargic, I couldn’t concentrate on my form or the game. I’m a minimalist golfer, and love it that way. I carry six clubs, each more than twenty-five years old, and still play a decent game. My favorite “golf” shoes are FiveFingers or running sandals. Our local course in West Virginia still encourages walking, and they allow me to run there during the early morning hours, too.

My father-in-law is in his nineties, and he walks the course (with four clubs). A few years ago, a group of young players in carts came upon him.

“How old are you?” one young man asked.

“Ninety,” he replied.

“Wow. I hope I can still get out on the course when I’m ninety,” the young man said.

“Then get out of the cart,” my father-in-law responded.

Golf can be a source of health and fitness for anyone. But the modern version of it—the electric carts, stiff shoes with spikes, and heavy bags with too many clubs—robs golfers of the experience of mastering the game from the ground up. In golf, as in running, the feet and their connection to the earth greatly affect what happens to the rest of the body, and how you perform.

DRILLS

The drills here are all about expanding mobility and range of motion. Each of these movements should leave you feeling refreshed and ready to go again the next day, not sore and unable to move. The quality of your movement is more important than how much weight you lift or how fast you perform a task or a drill. Three years from now, no one will care how well you performed in today’s workout, but injuring yourself is an event you’ll likely remember.

Whether you are a competitor or exercising for fun and fitness, train the pattern, not the part. The brain and nervous system do not recognize individual muscles; they recognize patterns of movement.

Exercise snacks between meals

“Exercise snacks” can help break up the day and get the blood flowing. I spend much of my hospital workday walking. Between patients, I often stretch and do gentle lunges and trunk twists. If you work in an office, exercise snacks such as these will keep you healthy and flexible. You can stand while chatting with a colleague or student, and phone conversations offer more opportunities to stretch and move.

When working from home, interrupt your day by going outside and completing chores, especially those that demand some physical effort. When you return to your desk (preferably a stand-up variety), you are physically and mentally refreshed, and noticeably more productive.

In the following drills, we are going to work on movements, not muscles, and progress from very simple to more complex. You need not do all of these, but they can populate the menu that you select from, depending on the level of challenge you desire, and how it fits in your day.

Let’s start with some mobility assessments.

Ankle mobility assessment

Place your right foot forward with your toes about four inches from a wall. With heels on the floor, try to bring your knee to the wall. Switch and assess the other side.

Hip extension assessment

Lie flat on a table and hug your knee (as your other leg hangs over the end of the table). When you hug your knee, does the other thigh elevate off the table? Assess both sides.

Quad length test (affecting hip mobility)

While lying prone (on your belly), bend the knee of one leg and bring your heel to your butt. Assess both sides.

Prone

Upright

Range-of-motion drills

Six-position foot walk

This simple exercise snack works the small muscles of your feet and ankles, and assists with balance and foot strength. Barefoot, preferably, walk in the following manner whenever you can (for instance, when walking the dog), initially for short distances. Walk:

-

On the outsides of your feet (inversion).

-

On the insides of your feet (eversion).

-

Toes pointing outward (Charlie Chaplin style).

-

Toes pointing inward (pigeon-toed).

-

On the balls of your feet, backward.

-

On your heels (you may need shoes, if not barefoot adapted).

The squat—rediscovering one of the most basic positions

Kids squat naturally and easily. Adults typically say, “I’m not built like a child anymore, and can’t get into that position.” It’s true that your body geometry is different, but to reclaim your flexibility and mobility, you still need to be able to squat.

The prime movers in squatting are the muscles around the hips and knees, but all joints below the belly button (hip, knee, ankle, foot) and most of the spine need stability and mobility for a proper squat.

Looks perfect! Just do your best to rediscover this.

Align your feet comfortably under your hips (or slightly wider). Then move directly to a full squat. As you do so, try to maintain a good, flexible posture, with your:

-

Head and thoracic spine upright.

-

Lumbar spine neutral, not hyperextended.

-

Arms in front and shoulder blades “tucked.” (Think of putting your shoulder blades into your back pockets.)

-

Hips mobile, sitting back as if tapping a chair behind you with your glutes (but not sitting).

-

Knees tracking directly over the toes. Use a resistance band around the knees, and apply outward pressure.

-

Shins close to perpendicular to the ground. (Your knees shouldn’t extend over your toes.)

-

Weight on your heels, and heels remaining on the ground.

Which does your squat look like? Aim for the picture on the left.

Progress to a deep squat (“ass to grass,” as they say). If your heels come off the ground, place a book or two under the heels and work on gradually removing them. This will help the mobility of the ankle. Vary the foot position. The goal is to hang out comfortably in a deep squat for a few minutes. But if you have any discomfort, restriction, or tightness in the knees, stop when your thighs are perpendicular to the ground. It may take time to work into a full squat.

or load yourself with a kettlebell, in an exercise called the goblet squat.

The wall squat

To further assess the mobility of the thoracic spine, stand with your toes close to the wall (or, ideally, right up to it). Raise your arms high overhead, and try to drop down into your basic squat. Can you get your thighs to a level parallel with the ground? Can you drop your bottom all the way down? Do this routine especially if your upper back is restricting you.

By working on upper body, hip, and ankle mobility, you’ll be able to do a wall squat.

Floor sitting

We should all be exploring the ground whenever we can. We can do this (without spending extra time in our day) by sitting on the floor. Here are five floor-sitting positions, in addition to the deep squat, that will greatly boost your flexibility and range of motion:

Kneeling. Lost from most Western cultures, this requires quad and ankle mobility. Use a pad for your butt and knees if you’re uncomfortable. As an interim measure, try kneeling on one leg while doing some of your work. This will build hip and core stability.

Long sitting. Sit with both legs extended, straight out. This builds hamstring mobility. Tuck one leg in for variation.

Cross-legged, or “Indian style.” Tight IT bands and piriformis will cause the knees to elevate. Work to keep the knees lower. As a variation, place the soles of your feet together.

Side sitting. Place one leg in internal rotation and the other in external rotation. Change sides, and assess tightness and symmetry. This can be challenging.

Upper body mobility

T-spine foam roll

Move into these positions slowly, with diaphragm breathing, to open up your thoracic spine.

Move slowly up and down each segment, while deep breathing.

Move shoulders and arms as if making a snow angel

Supple hips

The windshield wiper progression

This exercise generates good internal and external rotation of the hips, with glute firing and hip extension. It’s especially good for golfers, who need at least 25 degrees of internal rotation of the lead hip on the backswing, and the same on the other hip on follow-through. (The average PGA golfer has 45 degrees of internal rotation.) If you don’t have this range, you’ll end up compensating elsewhere in the kinetic chain.

-

Lie on the floor, with back flat, arms stretched straight out, knees bent at 90 degrees, and heels on the floor.

-

In a slow, smooth motion, sweep your knees back and forth, to the right and then to the left, in a windshield wiper motion. Keep your shoulder blades on the floor, with arms extended. Repeat ten to fifteen times.

Heel raises

Foot control is essential to running, and helpful in all activities. Simply balance on one foot, raise up on the ball, and finish by loading weight onto the big toe and rotating the lower leg slightly toward the big toe (to get maximum plantar flexion). This is the full range of motion employed when walking and running correctly. Slowly lower yourself, with control, to the start position. If you can, knock off fifty to one hundred of these on each foot daily. Progress from the ground to lowering from a step.

Single-leg sit-to-stand

This simple and revealing exercise can be done while sitting in your office chair:

-

Sit on the chair with your feet flat on the ground.

-

Select one leg, and elevate slowly on that leg, with arms extended overhead. Pause on the ball of the foot, then lower yourself slowly, in a controlled manner. Don’t let your knee collapse inward.

Single-leg hop

Another simple (but somewhat challenging) stability drill is to simply hop on one foot ten times. If you’re unable to do this without pain, or are wobbly, return to the single-leg sit drill above, and progress to this.

Fire hydrants

This move assists hip mobility and strength in both extension and abduction, which are essential for running. On all fours, elevate and extend one leg, and draw large circles with it, clockwise, then counterclockwise. For an additional challenge, extend the opposite arm directly forward into the “bird dog” pose.

There are three tests of hip, glute, and core stability. Hold each of these positions for one minute:

Bridge single leg

Lying on your back, tuck one knee to the chest and tighten the glutes. Then “bridge” (elevate) your core upward.

Plank

Lie prone on a mat or the floor. Place your forearms on the mat, elbows under shoulders. Place the legs together. Elevate your body into a straight line. Hold for thirty to sixty seconds.

Side plank

Lie on your side on a mat or the floor. Place your forearm on the mat, perpendicular to the body. Place the upper leg on top of the lower leg and straighten your knees and hips. Raise your body up until it is rigid. Hold for thirty to sixty seconds. Repeat on the opposite side.

Video assistance

My colleague Jay Dicharry and I demonstrate some excellent assessments and corrections for improving range of motion and stability in “Are You Ready to Go Minimal? 3 Self-assessment tests with Jay Dicharry,” on the videos page of runforyourlifebook.com.

Once you have progressed by mixing these movements into your day, the final exercise is the Turkish Getup, which incorporates nearly all of the preceding exercises. This sequence (see the video by this name) will help you visually piece together this timeless exercise.

Turkish Getup up move

Reverse to slowly go down