CHAPTER 14

Outsmart Injuries with Prevention

Why are pain and movement linked? In the presence of acute injury and/or pain, if the nervous system concludes there is a threat to the tissues, then movement is the primary mechanism by which the nervous system can react to that threat.

—Grieve’s Modern Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy

MYTH: Running wears out the joints.

FACT: Joints benefit greatly from stress and impact, in the right amounts.

More than half of all runners are injured each year.

Let’s take a look at one subset of active people: enlisted men and women in our Air Force. In 2010, running ranked only behind basketball as the leading source of injuries. (Many of those b-ball injuries are running-related, too.) But that’s minor compared to what the armed services see overall. The Department of Defense reported 8.3 million days of missed duty between 2005 and 2009 from preventable musculoskeletal injuries. These include overuse injuries, sprains, strains, dislocations, tears (ACL/cartilage), and spine problems, costing the military $1.5 billion a year in labor replacement, medical care, and long-term disability.

CHASED BY AMBULANCES

What’s going on with all this injury? Why do so few medical studies adequately explain their complicated causes, and why does the medical profession offer little beyond reactive, symptomatic treatment? Running injuries are typically treated with rest, ice, injections, painkillers, stretching, MRIs, fancy tests, and various devices and shoe orthotics. But despite all this medical “care,” evidence-based trials show that much of it doesn’t work. Runners continue to get injured at consistently high rates.

I find this heartbreaking. It’s too easy a progression for an injured runner to become a former runner. When we are offered only drugs, cumbersome interventions, and ineffective treatment for pain or injury, quitting running is a logical response.

SHIFTING THE KINETIC CHAIN OF COMMAND

Runners are at fault, too, though not intentionally. When we feel pain or an incipient injury, we tend to shift our gait or posture. But a compensation like this (along with the drugs or orthotics) can hide the original condition or trigger another injury in a different area of the body. Sometimes a domino effect of injury works its way up (or down) the body’s kinetic chain.

Injuries seldom happen in isolation, and never without cause. I often see runners suffering from a cascade of injuries; finding the root cause requires tracing back through the series of accommodations the runner has made. Not uncommonly, a debilitating injury starts with something seemingly benign, such as a single ill-fitting shoe. Over time, this can progress to weakness and lack of control of the foot, which can cause or contribute to lower back pain.

As I work with a runner, I try to determine which tissues feel pain, and when and where onset of pain occurs. Some areas are more sensitive than others, such as the fascia of the feet, the small tendon insertions, and the lumbar fascia of the back. Pain in the joints and bones tends to appear later, as a delayed response, and it’s not unusual to develop knee or hip arthritis, for instance, before the area becomes painful. In the case of stress fractures (especially in the foot), pain might arise only after the injury has progressed—and sometimes when bone scans or MRIs show multiple asymptomatic (painless) stress on the opposite side, distant from the affected, painful area. In other words, runners can injure themselves without feeling pain. Unaware of a developing injury, they run themselves into a fully injured state.

Too often, the sports medicine industry is inadvertently (or intentionally) complicit in all this pain and injury. Sports medicine responds efficiently to dramatic, gladiator-style trauma and orthopedic injuries. For a blown-out knee from a football tackle, for example, repair teams can rebuild you. But for injuries suffered from thousands of slightly misaligned micromovements, or repetitive stress, we are way behind. And, as we saw in chapter 11, standard treatments such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and other NSAIDs actually inhibit healing.

All of this underscores how essential it is for us to maintain—on our own, without too much intervention—the delicate relationship between our interconnected moving parts. It’s mainly up to each of us to build the ability to respond to and prevent injuries. Running should not cause injury. It should make us injury-resistant, and injury-resilient. We run so we don’t get hurt.

AVOID THE LOADING ZONE

Fortunately, progressive-minded physical therapists and biomechanists have begun to teach running technique as part of their treatment for injured runners. In one study, Irene Davis, director of the Spaulding National Running Center, had subjects run in minimal shoes and bare feet on a specially configured treadmill that could measure ground impact forces. The runners were told to land softly and quietly, to increase their step count, and to listen to their own real-time feedback on landing patterns. She found that these subtle adjustments helped them to significantly lower impact forces on their lower legs, reduce pain, and (in some cases) resolve chronic injuries. This technique for modifying gait is called impact moderating behavior (IMB)—an important term that I hope will gain currency among everyone who runs.

Elite athletes mostly know this. Those who don’t have short careers. The wise ones learn that whenever they sense pain or discomfort, they need to understand the cause, address it, and encode IMB into their landings—not treat it symptomatically or surgically or rely on a shoe or insert to correct it.

I learned this the hard way myself. Earlier in my running years, I suffered a condition called hallux rigidus, in which I couldn’t dorsiflex (bend upward) either big toe—a result of degenerative changes likely caused by running too hard, with poor form, in overdesigned and poorly fitting shoes. Surgery relieved some of the pain, and some mobility returned, but the joint remained mostly fused. Doctors suggested that I quit running.

CHANGE MUST COME FROM WITHIN

Inexplicably, after surgery on my feet, no one prescribed foot strengthening exercises or physical therapy, which is the treatment for other sports injuries. I knew that I needed exercise, and I found nothing as convenient or relaxing as running. (My dog missed it, too.) So rather than quit running, I set out to retool the way I ran.

At the time, I lived in Denver near a wooded park that featured a 2.5-mile running loop with a forgiving crushed rock surface. Initially, I harbored only one objective: to get out and enjoy myself. I now believe this to be the most meaningful and sustainable goal that any runner can have.

Running at slow speeds gave me the space to breathe, and the time to explore commonsense techniques of impact moderating behavior. I tried shorter strides (with a quicker cadence), and landed with knees bent and feet closer to my center of mass. I began to understand what not to do, such as land hard on my heels. I experimented with running methods. ChiRunning helped me learn new things: it stressed biomechanics, not workouts, and taught me to approach running as a complete practice, not as a sequence of disconnected movements.

PREHAB, NOT REHAB

Running injuries aren’t inevitable. Most injuries are a product of too much, too soon, too hard, or too fast. Or a combination of these. We can prevent injuries in the first place by doing prehab: realigning the body’s symmetry, maintaining posture, strengthening the feet, expanding the range of movement, learning gentle rhythm and relaxation, and remodeling movement patterns. Treat the position, not the condition. The time to fix the roof, as JFK said, is when the sun is shining.

A low volume of high-intensity exertion can move someone above the injury threshold. Likewise, so can large doses of low-intensity work.

The goal is to gradually elevate the injury threshold, with workouts of low to medium intensity and duration.

We can also deter injury by unbinding and loosening physical restrictions, and building mobility—through careful mobility work and foam rolling. (Too much stretching, however, can be counterproductive. Picture trying to undo the knot of a rope by pulling it tighter.)

Your level of exertion affects vulnerability to injury, too. When you’re not overexerting (i.e., when you’re running within the comfortable, aerobic zone), you can better feel discomfort and sense incorrect form, and better judge when to stop. High-intensity running, by contrast, allows the hormones produced during the sympathetic, fight-or-flight response to mask structural pain. If you are running above your maximum aerobic heart rate, you may wake up surprisingly sore the next morning, or even find that you have an injury.

The prescription for healthy running, when starting from an injury-free state, is reasonably easy to fill: as you begin an exercise routine, progress gradually. Walking injuries are rare, so don’t be afraid to start by walking. Then progress to a walk/jog mix, and graduate to running.

WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON RUNNING INJURIES WE SEE?

There isn’t room here to discuss every running injury. Our attention, anyway, should remain on turning off the faucet, not on mopping up the mess. Medical counsel can appear contradictory: on the one hand, most injuries are curable without medical intervention. But on the other, if you are severely injured and in pain you should seek help from a medical professional who understands running.

Let’s take a look at the typical running injuries physicians see, and what can be done to treat them “post-actively” (for those of us who fell behind the prevention curve and exceeded the injury threshold). If you highlight a map of the body with common running injury hot spots (this page), you’ll see that the feet, lower legs, knees, and back light up most vividly.

Problem knees account for a large percentage of running injuries every year. Common knee and upper leg conditions include:

-

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS)—pain on the lateral (outside) aspect of the knee.

-

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS)—pain on the underside of the patella.

-

Hamstring sprains/strains—injury is usually where the hamstring crosses joints (knee and hip); most injuries occur high in the hamstring.

Foot, ankle, and lower leg problems account for another large percentage of running injuries. The four most common of these conditions are:

-

Achilles tendinosis—chronic inflammation and degeneration of the Achilles tendon.

-

Plantar fasciosis—degeneration and microtears of the plantar fascia of the foot.

-

Medial-tibial stress syndrome (commonly referred to as shin splints)—usually early stage microfractures that occur along the inside edge of the tibia.

-

Stress fractures—progressed microfractures that most commonly occur in the tibia, metatarsals, or calcaneus.

Generally, muscle injuries occur when one’s range of motion is exceeded, and when tissues are abnormally stressed. Bone and joint injuries tend to result from high or repetitive impact (abnormal loading).

Knee valgus is the motive force behind the epidemic of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in jumping and explosive sports such as basketball, volleyball, and skiing. Less commonly, ACL injuries can also occur from lower-impact, highrepetition movements, such as running.

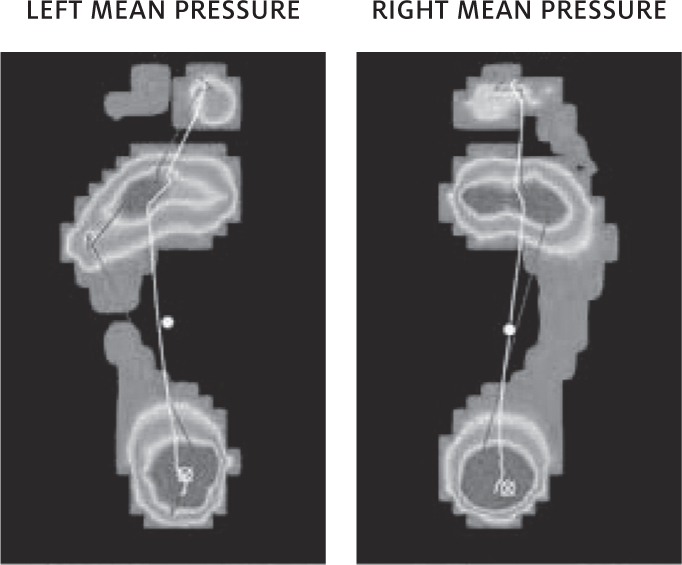

Assessing the foundation: at Two Rivers Treads we use a plantar pressure map to assess and retrain the foot to proper shape, strength, and balance.

The relatively new regimen of core and hip training is designed to deal with valgus movement, by stabilizing the stance and preventing the femur from rotating inward on landing. Despite a decade of experience in the athletic community with this core and hip training, however, valgus-related injury rates are still high. Curiously, in the early days of running, these injuries were rare—most people simply ran correctly. Little attention was given to accessory core training, and if runners wanted to build strength, they ran and bounded up hills.

Dynamic knee valgus, it turns out, typically begins with the foot. The knee is more like the kid caught in the middle: it’s only doing what the hip and the foot tell it to. A weak and unstable foot—one that can’t control impact loads, then collapses—takes the knee along with it.

The image above illustrates “dynamic knee valgus,” in which the knee dives inward in an “L” shape, commonly seen during high-impact movements such as jumping and landing. Movement sequence A ? B ? C can lead to anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) tears.

If the hip is strong and the foot is weak, the knee will collapse. This is one reason why I don’t recommend shoes with excessive support or marshmallow-soft cushioning. The foot is your foundation, and it needs to be strong and solidly planted on the ground.

PLANTAR FASCIOSIS—A LIFESTYLE INJURY

Plantar fasciosis is not primarily a running injury—it’s a common malady. But every week or so, the Natural Running Center receives a query from a reader desperate for relief from chronic plantar fasciosis pain. Fortunately, the approach to treating it is fairly straightforward, and can be applied to other injuries. (Technically, fasciosis refers to a degeneration of the tissue, which is far more common than fasciitis—the conventionally used term. Fasciitis implies true inflammation, and occurs in situations such as infection or autoimmine attack. Similarly, Achilles tendonosis is more common than tendonitis.)

The strong, springy plantar fascia tendon maintains the arch of the foot. It creates tension between the calcaneus (heel) and the metatarsal heads, forming the depressable arch that acts as the foot’s primary spring, like a leaf spring on a car.

The plantar fascia is designed to manage a limited amount of stress. The intrinsic muscles (those solely in the foot) and extrinsic muscles (those attaching the foot to the lower leg) receive signals from the nerves and fascia, and it’s these muscles that should absorb and manage most of the load. When those muscles become dysfunctional or weak, the load is transferred to the plantar fascia, where repetitive stress causes microtrauma, and eventually plantar fasciosis.

Plantar fasciosis tends to recur, for the simple reason that sports medicine does little to prevent it. I suffered from it for years, such that even walking became a miserable, painful experience. Injections, night splints, over-the-counter arches, rigid custom arches, stable shoes, stretching—nothing helped. If shock wave therapy had been in vogue, I’m sure I would have tried it.

For sufferers like me, typical first treatments include arch supports or NSAIDs, neither of which are effective in the long term. Arch supports may provide some relief, but they only serve to brace and weaken the arch. (Some structural foot deformities can benefit from supports.) Always, the goal is improvement in function and strength. Anti-inflammatories only circumvent the natural repair process, and pain recurs as soon as the stress is reapplied.

The only way to sustainably fix plantar fasciosis is to address the root causes. Is the runner suffering from fallen arches, or is it failing arches? Gradually reducing and removing arch supports, while building foot strength and moderating impact, is the best place to begin. Paradoxically, shoes that offer lots of support weaken the foot, causing more foot instability.

Other factors can contribute to plantar fasciosis, such as a misaligned and weak big toe, tight and shortened calf muscles, obesity, or transitioning too quickly from supportive footwear to flat shoes or bare feet.

Treatment for plantar fasciosis varies, depending on the cause, but as a general guideline:

-

Orthotics such as arch supports or taping should be used only as a temporary modality while you strengthen and lengthen tissues. (You don’t leave a broken arm in a cast forever; muscles begin to atrophy from disuse within a week.) Don’t wear heels, and find shoes with wide toe boxes.

-

Place your forefeet on a stair, and lower your heels, then raise them. It’s fine to feel a bit of discomfort while doing this, as long as you are progressively increasing strength and control of the feet. This is great for the Achilles tendon, and the tibialis posterior muscle and tendon, too.

-

Do some soft tissue work to loosen the plantar fascia if it is thickened, tight, and tender. Forcibly work the soles of your feet with your thumbs, rollers, or even golf balls, to release the fascia knots. Healthy fascia slides and glides.

-

Work the intrinsic muscles of the feet. Pick things up with your feet. Walk barefoot. As often as you can, strengthen the muscles of the big toes by dorsiflexing them, then pressing them into the ground—toe yoga. This will awaken the foot muscles and help re-create the arch. The short foot posture exercises can be done throughout the day, too, even inside your (flexible) shoes. (Barefoot Science insoles can stimulate these muscles all day.)

-

If your big toes are misaligned and bent inward (hallux valgus), which is common, consider using a product to straighten them, such as Correct Toes.

-

Practice slow jogging, with lighter ground contact and loading rates. Relearn how to land and spring. Easy jump-roping teaches this, too.

-

Avoid NSAIDs (naproxen, ibuprofen, etc.). These drugs interfere with natural healing processes, and can cause medical complications. In college, I suffered a bleeding ulcer from these meds, and lost over half my blood volume.

-

Consult a health care provider who understands natural running and walking.

A collapsed foot creates strain and microtears of the plantar fascia.

HANDIATRY?

Why have our feet become such a problem, and why are there so many podiatrists? Look at your hands, and ponder why we don’t have “handiatrists.” It’s because we utilize our hands daily for a wide variety of tasks. We run them through an extraordinary range of healthful motions—unencumbered by heavy, confining, posture-altering gear of the sort that we routinely wear on our feet. Remove the shoes or wear minimal ones, and many foot problems will go away (with time and patience).

RESET, NOT REST

Misperceptions abound. Some injuries require rest and rehabilitation, but many don’t.

One runner, Natalee Maxfield, played on sports teams in high school, then picked up running in college, married, and ran throughout her pregnancies. In her thirties, she developed foot pain, which podiatrists variously ascribed to Morton’s neuroma, plantar plate injury, and capsulitis. They prescribed rest and orthotics. But she didn’t want to stop running.

Natalee sensed that she would need to find lasting relief on her own, and that the best therapy would be to simply not get injured in the first place. She adjusted her running style, switched to shoes with a more minimal profile, and hasn’t been injured since. As Natalee and others have learned on their own, many running injuries require correct remodeling, not medical intervention or rest.

Any time a tissue endures strain (in which it is stretched and lengthened), it is deformed. Picture what happens when you bend a ski pole: under stress, it flexes and springs back to its original shape—up to a point. When strained or overstressed, it becomes stuck in a new, bent position, requiring that it be forcibly restraightened in order to be useful. This is what happens when a shoulder, for instance, is secured in a sling. In as little as three days it freezes in that position. The process of remodeling it correctly—getting it to work again through its full range of motion—is painful and difficult.

If you are suffering from a running-related pain, the joints—indeed, all parts of the body—generally benefit from movement of the affected area, not immobilization. Running (and walking) the right way is an excellent treatment for degenerative injuries sustained from running the wrong way. In my practice, I continually witness the body’s remarkable ability to heal itself and restore itself to its natural position—while people remain active—if the causative issues are addressed and the right signals are sent.

Mistakenly, many of us are “rehabbing” basic movements and skills out of ourselves by focusing on an isolated exercise. Imagine seeking guidance from six golf swing coaches—a backswing coach, a stance coach, a strategist, and so on. You might succeed in improving the movement of a single specific muscle group, yet you’d still have a dysfunctional swing.

AS YOGI BERRA MIGHT HAVE SAID, HALF THE PAIN WE FEEL IS 90 PERCENT MENTAL

Pain management is a persistent challenge in the treatment of running injuries. And one of pain’s enduring mysteries is the manner in which we anticipate it. (Note that it’s the brain and nervous system that register and process pain, not the injured part.) Experiments have looked at how people respond to a painful stimulus applied to someone else’s limb, or to a sham limb, that is placed in a position where it appears to be one’s own. (See Dr. Lorimer Moseley’s TED talk, “Why Things Hurt,” linked on the videos page of runforyoulifebook.com.) PET scans show that subjects can experience genuine, objectively measurable pain—from a physical stimulus that doesn’t exist.

Why do we feel pain in the first place? For one thing, it’s a signal telling us that we need to protect tissue that is harmed or at risk. To the extent that it correctly alerts us to the problem, pain can protect us from further damage. But the signal can have a lag time, or come from an area that isn’t the actual source of stress.

In other words, the patient and the doctor can misinterpret the signaled pain. Even worse, when doctors offer symptomatic treatment (the easy, billable solution), they leave the root cause of the pain unattended and untreated. The simple binomial that pain is bad and relieving pain is good is a simplistic response that seldom translates into appropriate medical treatment. Indeed, this approach has guided us directly into the current opioid addiction crisis.

When it comes to running, changing your mental approach can do wonders. Running coach Elinor Fish urges that simply shifting your mind-set from running causes injury and pain to running makes me injury-resistant will reduce your chances of developing an overuse injury. “With a positive mind-set,” Elinor says, “you set the stage for establishing new habits that support running as a lifelong practice. While it’s easy to view running as the cause of your injury, it’s more likely that running is just making you aware of a preexisting problem. For example, sitting all day long causes chronic shortened hip flexors and underdeveloped glutes, both of which make running more difficult.” The pain and stiffness and sensitivity arise when you are out running, so we don’t automatically make the connection to the real cause: sitting.

AN EXPERIMENT OF ONE

Ultimately, a doctor or physical therapist can’t know you intimately, and you need to rely on yourself as diagnostician and medical researcher—with yourself as the patient and experimental subject. Each of us responds differently to exercise, to physical stress, to the numerous insults that our bodies face as we move across the surface of the earth and interact with the objects on it. Ultimately, your personal experiment should seek one important outcome: to avoid injury. Do not put pain into your body. In place of the aphorism No pain, no gain, we should approach our activity with the conviction No pain, thank you.

DRILLS

Evaluating someone standing in a rested state provides a physical therapist with only part of a picture. The therapist—you, in this case, examining yourself—needs to see what happens under load, and especially in a fatigued state. Take a look at a sequence of pictures of yourself in a race: you look pretty good in the early images. By the end it’s a different story. As you fatigue, your posture and form change—almost never for the better.

A high-speed smartphone camera can reveal a lot. Try video recording the following:

-

A single-leg step down from a low platform. Watch what is happening at the foot, the knee, and the hip. If the knee collapses inward, try to notice what gives out first. Is it the foot or the hip?

-

Ten hops on a single leg. This shows what happens under a bit of load. Then magnify the response and fatigue yourself by doing three or four minutes of shuttle runs, a few burpees, some jumps, and a few sprints. Then do the single-leg step down and single-leg hop tests again. Notice the difference? Even elite athletes will show weaknesses. (Do this fatigue test cautiously, and only if not injured.)

Identify and correct any “pathokinematic” (dysfunctional) movement pattern before you train for your next marathon. Build strength and follow gait cues. Don’t overstride. From the frontal view, land with each foot directly under the hip (as if ascending stairs). Think of running on a line, with each foot landing on either side of the line, never touching it.

My foot lands directly under my hip, as if stomping grapes.

Inure yourself to injuries

The objective of the following drills is to protect yourself from injury and pain. Here are some simple ways to short-circuit the repetitive stress and high impact that typically result in injuries.

-

Rather than run the same route each time you go out, alter the path you take. Changing up your route lets your body adapt to different environments. Trail running, for instance, improves balance and muscle strength (though it comes with the risks of unpredictable terrain). Soft grass or sand offers a cushioned landing for runners, but requires more muscle use, because there is less energy returned when your foot strikes the ground. Mix it up. Throw in some new challenges, and enjoy—but make the changes gradually.

-

Transition—again, gradually—from a heavily cushioned and supportive shoe with an elevated heel to a minimal shoe that is flatter, lighter, thinner, wider, and more flexible. Your freed-up feet will thank you.

-

Listen to your body. Don’t mask discomfort with pain medication or anti-inflammatories. Slow down, add gentle and progressive stress, and recover. Then notice what you’re no longer noticing: pain, soreness, and stiffness.

-

Along with the TrueForm Runner (a remarkably useful tool for gait retraining and injury prevention), try the Zero Runner. This no-impact trainer allows for full range of motion in the hips, and variability of movement. (An elliptical trainer or Stairmaster, by contrast, dictates your movement.) If you are recovering from a stress fracture, joint replacement, or other mechanical stress or overload-related injury, the Zero Runner (which is great fun) can get you back in the game.