CHAPTER THREE

What Germany Did

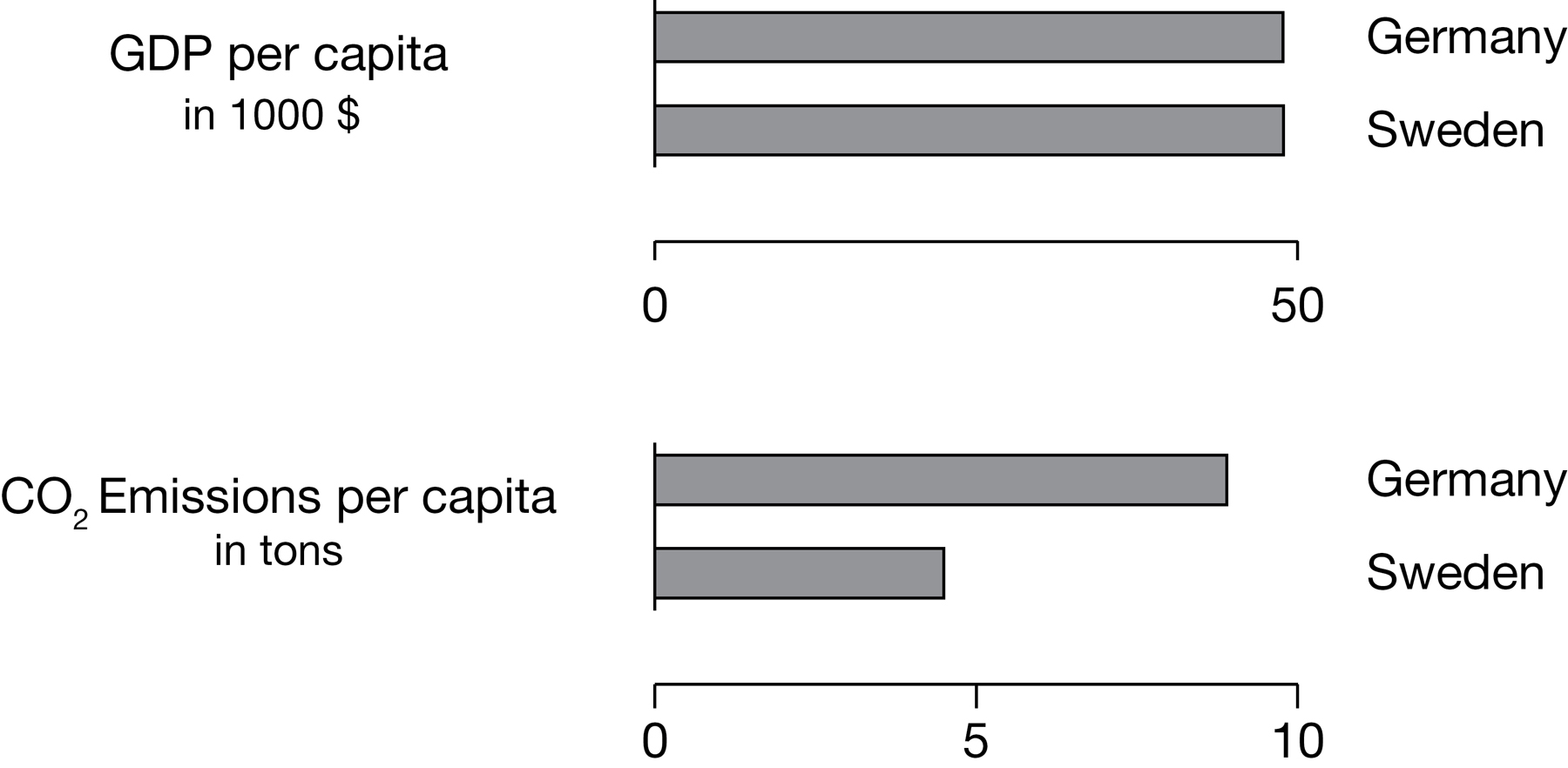

SWEDEN’S NEIGHBOR GERMANY has taken a very different path. Both are northern European, industrialized countries with successful economies. The GDP per person is almost the same. Sweden uses one-third more energy per person than Germany. Yet Germany emits about twice as much carbon pollution per person. Why is that?

Germany has received a tremendous amount of favorable publicity for its green Energiewende (energy transition) policy of installing large capacities of renewables—mostly wind and solar power. But how does that approach work out in terms of the world’s need for rapid decarbonization?

In the past decade, Germany has roughly doubled its production of energy from renewables, an impressive accomplishment. In 2016 renewables made up more than a quarter of electricity production and almost 15 percent of total energy production.

Figure 8. German versus Swedish emissions. Sources: GDP: World Bank (PPP), 2016; CO2: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, 2014.

But here’s the catch: While it doubled renewables, Germany cut nuclear power by roughly an equivalent amount. It just substituted one carbon-free source for another, and CO2 emissions did not really decrease at all. In fact, they have gone up slightly in recent years. And this will continue in coming years because, after the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan, Germany is phasing out its remaining nuclear power in the next few years. The decade during which we desperately need to be rapidly decarbonizing will be a lost decade for Germany.

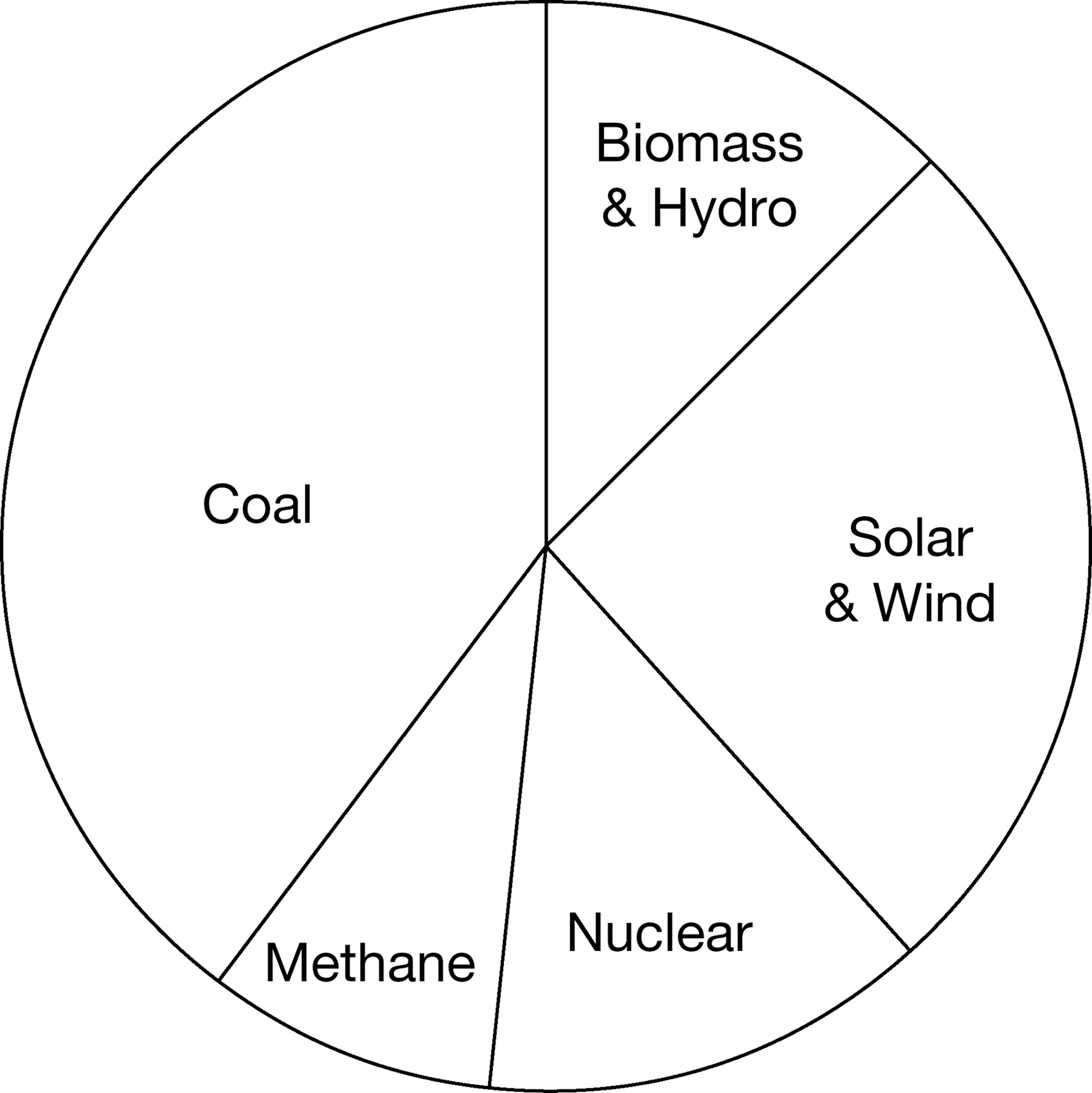

German energy remains dominated by fossil fuels, specifically coal, and not just coal but an especially dirty CO2-heavy type of soft coal called lignite. In Germany’s electricity production, lignite alone supplies almost a quarter, and all coal supplies 40 percent. Renewables are 29 percent and growing, but nuclear power is 13 percent and shrinking.1 The coal burns on. Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions remain around a billion tons a year.2 If Germany had used its new renewables to replace coal, instead of to replace nuclear power, the CO2 emissions picture would be quite different.

Figure 9. German electricity fuel mix, 2017. Data source: Fraunhofer ISE Energy Charts.

Germany’s three biggest coal-fired power plants all burn lignite coal. One of them, the Jänschwalde power plant, is located about 400 miles south of the Ringhals nuclear power plant in Sweden. At Jänschwalde coal from nearby strip mines is brought to the plant in trains and burned to boil water and run steam turbines. The electricity goes onto Germany’s electric grid, which is integrated with northern Europe’s grid. In a good year, the plant produces almost as much electricity as Ringhals (20 TWh/year),3 but it does so in a dramatically different way.

Jänschwalde burns vast quantities of coal and emits vast quantities of CO2. On average it burns at least 50,000 tons of dirty coal per day.4 If you loaded that coal into a single coal train, it would stretch 5 miles long. If you made elephants out of coal and burned them to boil water, you would march about 10,000 elephants into the maw of the great machine every day. The next day, another five miles of coal train, or another 10,000 elephants. The CO2, more than 60,000 tons daily, is not captured and sequestered; it is dumped into the atmosphere.5 A fair estimate of the deaths caused by the air pollution from this one coal plant is about 650 people per year, with 6,000 additional people suffering serious illness.6 Germany has two other similar lignite coal plants and a number of smaller ones.

Figure 10. German lignite coal strip mine with the Jänschwalde plant in the background. Source: Courtesy of Hanno Böck.

On the World Wildlife Federation’s list of the most polluting power plants in Europe, measured by CO2 emissions per unit of electricity produced, Jänschwalde is number four. Six of the top ten are German.7 In 2016 the German state secretary for economic affairs and energy predicted that Germany would continue to burn lignite coal until after 2040.8

The company that owns the Jänschwalde plant sees coal as integral to Energiewende: “The expansion of renewable energies and the phasing out of nuclear energy by 2022 are the two main objectives of the ‘Energiewende’ (energy transition). Our lignite power plants accompany this process. On the one hand, they offer a reliable round-the-clock supply and on the other hand, they are flexible and capable of adjusting their own production to the current available renewables which have the right of way in the transmission grid.”9 In 2015 a top executive of the then owner of Jänschwalde discussed coal’s role in supplying Germany’s projected need for 20 to 50 GW of baseload generation: “Nuclear power plants will be decommissioned in a few years. This means that only lignite and hard coal fired power plants will be left for base load generation. In Germany we currently have around [20 GW] installed capacity in lignite-fired power plants. I am convinced that we have to retain this capacity on the long-term.… Lignite will continue to play a considerable part in the future energy mix in the next four to five decades.”10

Wind and Solar

Germany has adopted a policy to switch its economy to renewables. If the country first cut fossil fuels rapidly and then transitioned from nuclear power to renewables, this policy might be defensible. Instead, Germany is running in place by reducing clean nuclear power as it increases clean wind and solar.

Wind and solar power are wonderful, but they start from a very small share of our energy systems, and, to date, they have not been a fast way to replace fossil fuels. They are inherently diffuse in contrast to concentrated energy sources, including both coal and especially nuclear power. And they are variable and uncertain.

Consider the largest solar power facility in Europe, the Solarpark Meuro in Germany. It covers about 500 acres on a former lignite coal strip-mining site. This is an excellent use for a former coal mine, and the 166 megawatts (MW) of solar power are essentially carbon-free.11

The problem is twofold—scale and timing. Even though Solarpark Meuro is the largest solar site in Europe, you would need twenty of them at peak capacity to equal one Ringhals or Jänschwalde. Worse still, that peak is produced only during the best season, the best weather, and the best time of day. Every night, every winter, and every cloudy day, production is closer to zero. As a rule of thumb, nuclear power produces at 80–90 percent of capacity on average over the year, coal at around 50–60 percent, and solar cells around 20 percent. So to get the actual electricity production of one Jänschwalde would require about seventy Meuro solar farms. As solar prices drop, Germany might one day build those seventy huge solar parks, and might even use them to attempt to “replace” Jänschwalde instead of replacing nuclear power plants, but even then the power would not be available at the times it is needed, so backup power from fossil fuels would still be needed. Clearly, such an approach is not a formula for rapid decarbonization.

Figure 11. Solar farms such as this one in France, or Solarpark Meuro in Germany, require large land areas. Photo: Mike Fouque / Shutterstock.

Wind power is more important than solar for Germany. Many wind turbines have been built in recent years, mostly on land rather than offshore because it typically costs less. Germany does not have massive wind farms that could begin to compare with power plants such as Jänschwalde, but it could build these along the lines of Europe’s largest wind project, Fantanele-Cogealac, in nearby Romania, built in 2008–2012.

The Romanian wind farm covers 2,700 acres, about three times the size of Central Park in New York. The 240 wind turbines are each as tall as a fifty-story skyscraper, and the diameter of their rotors is thirty stories tall.12 So how much electricity does all that steel and concrete generate? The total peak capacity is 600 MW, about one-sixth of Jänschwalde. But wind is only somewhat more reliable than sunshine, and production in 2013 came in at below 25 percent of peak capacity.13 To equal the production of one Jänschwalde would take about 13 wind farms of this size, equipped with modern, state-of-the-art wind turbines.14 Even then, that production would not happen when needed, but variably, sometimes too much and sometimes too little.

Figure 12. A small part of the Fantanele-Cogealac wind farm in Romania, Europe’s largest. Photo: Courtesy of ČEZ.

In Germany wind has been somewhat unreliable. From 2015 to 2016, Germany added 10 percent more wind capacity but generated less than 1 percent more electricity from wind, because the wind did not blow as much that year.

In 2017, as Germany integrated solar and wind onto the grid—still just 7 percent and 12 percent of generation respectively, very far from 100 percent—intermittency began to affect the grid significantly. As one German grid operator put it, “We have a lot of stress on the grid.” Although solar and wind generation frequently dropped to near zero at some times, it surged to exceed demand at other times, even with the greatest practical short-term cutback of coal and nuclear production. More than a hundred times in 2017, sometimes for more than a day at a time, electricity prices went negative. Grid operators paid large consumers as much as 6 cents/kWh (almost 10 cents on one occasion) to take power to avoid overloading the grid.15 Until someone invents a supercheap battery with huge capacity—no time soon, it appears—this instability from relying on wind and solar power will only worsen.

You might think that unevenness in supply would even out across countries, given a large integrated regional grid. “The wind is always blowing or the sun shining somewhere,” according to this line of thinking. But our analysis of the eleven top wind-producing countries and five top solar-producing countries in Europe in 2013 showed a period of forty-eight hours in which wind produced at only 6 percent of capacity across the whole continent, an entire month in which solar produced at only 3 percent, and a week in which all wind and solar combined across Europe produced at less than 10 percent of their capacity.16 During that week, powering the European continent with wind and solar power would require installing either massive redundant capacity that would sit idle most of the year or an extensive fossil-fuel infrastructure able to supply almost all of the electricity demand in Europe during the periods when renewables dropped out.

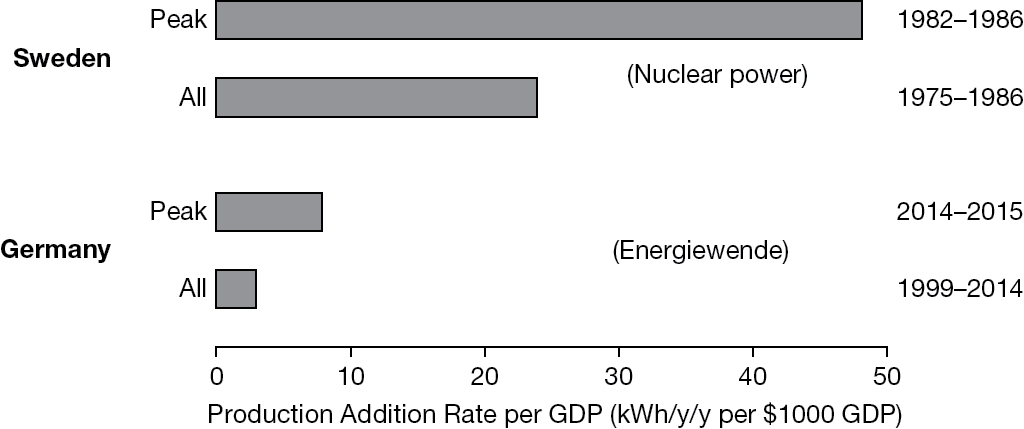

In addition to the intermittency problems, Germany’s massive rollout of renewable power does not match the speed of Sweden’s nuclear power rollout decades earlier. During the very fastest period of adding renewable electricity in Germany (2014–2015), the expansion relative to GDP size was less than a third of the rate of Sweden’s expansion of clean energy during its decade of nuclear power rollout and one-seventh of the peak rate in Sweden. This means that what the world might achieve in, say, twenty years using Sweden’s kärnkraft model would take more than a hundred years using Germany’s Energiewende model. Those are a hundred years the world doesn’t have.

Figure 13. Rates of clean energy additions relative to GDP during peak periods, Germany versus Sweden. Source: Generation data for all countries are from British Petroleum, BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2017). Population and GDP data in constant 2005 dollars are from World Bank Databank, World Development Indicators (2018). Gross nuclear generation values from BP are reduced 4.1 percent to obtain net values.

Several conclusions jump out from Germany’s experience. First, in order to rapidly decarbonize, a country must shut its largest, dirtiest coal-burning power plants and must mobilize any available resources such as new wind and solar capacity toward that end. Second, adding renewables to the mix is an excellent thing to do, but these sources alone cannot scale up quickly enough to rapidly decarbonize, especially given the intermittency problem. Third, phasing out nuclear power is in direct competition to phasing out coal. Every nuclear gigawatt closed down is a fossil gigawatt that continues to burn.

Germany’s failure to learn these lessons explains why it continues to spew twice the CO2 relative to economic activity as Sweden does. When it comes to a green economy, Germany talks the talk, but Sweden walks the walk.

A key difference between Sweden and Germany is that Sweden uses both nuclear power and renewables—equal parts hydropower and nuclear power with a growing wind component—along with biomass cogeneration plants for district heating. This approach recognizes that fixing climate change requires all the tools available and does not afford us the luxury of picking only those we like best, since they can’t succeed in isolation.

We can call the Swedish combination of nuclear power plus renewables “nuables.” It adds up to a solution that works. Nuables are doable.