CHAPTER SEVEN

Safest Energy Ever

IN 2011 A massive earthquake and tsunami hit the east coast of Japan, a bit north of the Fukushima district. In the fishing town of Onagawa, a nearly 50-foot wall of water destroyed everything and left hundreds of survivors homeless. They fled to the safest and most secure location they knew about, the Onagawa nuclear power plant. There they sheltered and received food and blankets. That’s right—sometimes the safest place to be in an epic natural disaster is your local nuclear power plant.1

Onagawa’s three reactors, dating from the 1980s and ’90s, had a capacity of more than 2 GW of electricity, more than half that of Ringhals in Sweden. Like in Sweden, the reactors had operated for decades without a major accident. On the fateful day in 2011, the plant’s 46-foot-high seawall prevented major flooding, and despite a lot of earthquake-caused cracks in the building, the reactors all shut down normally and without incident. No radiation was released; nobody was hurt.

Down the coast a bit, and twice as far from the epicenter, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant did not fare as well. The reactors there depended on backup diesel generators to keep coolant flowing, and although there were many of these backups, they were all flooded by the massive tsunami, which overwhelmed the plant’s seawall, whose height was less than 20 feet. (Note that the problem was not the reactor design but the unforgiveable decision to locate all the backup generators together in a location vulnerable to flooding with too small a seawall.) Over several days, among various problems in several reactors, the core of one reactor overheated into a radioactive mess and released hydrogen gas that exploded, breaching the containment structure. Radioactivity leaked into the surrounding environment and ocean. A panicky, botched, and almost entirely unnecessary evacuation ensued, displacing hundreds of thousands of residents in the area.

How much harm that radiation did is a subject of controversy. But if you trust science, you should believe the conclusions reached by the extremely thorough studies done by several UN agencies, including the World Health Organization. These experts all reached the same answer to the question of how many people were killed, either directly through high radiation exposure or likely to die later through elevated rates of cancer in the population. That answer: approximately zero. (We will discuss this conclusion in more depth at the end of this chapter.)

The health risks from the Fukushima reactors (even when employing the most conservative analysis possible) were in fact so low that in retrospect, the optimal response would have been to not evacuate anyone.2 The unnecessary evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people may have caused about 50 deaths among patients moved from hospitals,3 and as many as 1,600 deaths in the longer term, owing to elevated mortality from causes such as obesity, diabetes, smoking, and suicide among psychologically stressed evacuees.4 It is hard to know how many critically ill patients would have died absent the evacuation and how many psychological stresses should be attributed to the evacuation rather than the earthquake/tsunami disaster itself. Mortality rates returned to normal levels after about a year,5 although more than 100,000 evacuees remained.

Elsewhere in Japan, by contrast, the earthquake and tsunami themselves killed about 18,000 people, injured many more, and caused hundreds of billions of dollars in damage. It was, after all, the largest earthquake in recorded history in Japan and the third largest ever worldwide. Yet, just five years later, the trauma of this epic disaster seems all but lost in the world’s collective memory, and discussion of the event focuses on the Fukushima “nuclear disaster.” In truth, there was no nuclear disaster at Fukushima. There was a natural disaster of biblical proportions, a small consequence of which was a very expensive and disruptive but nonlethal industrial accident at the Fukushima power plant, followed by an unnecessary and botched evacuation.

Figure 24. Tsunami damage near Fukushima, 2011, unrelated to the subsequent nuclear power accident. Photo: Toshifumi Kitamura/AFP/Getty Images.

What happened next, however, killed thousands of people. Japan and Germany panicked (there is no better term for it) about nuclear power and shut down perfectly good, safe nuclear power plants. Japan closed fifty-four reactors and Germany eight more. Almost all remain closed six years later. These were inevitably replaced mostly with fossil fuels, including a lot of coal, and those fossils polluted the air with their particulates and toxins, increasing cancer and emphysema in the population.6 Although an exact estimate is difficult to make, the deaths from this switch to fossil fuels were certainly in the thousands each year, or easily more than 10,000 over six years.7

So here is an accounting of the toll of the 2011 earthquake/tsunami: earthquake and tsunami disaster, 18,000 killed; nuclear power “disaster,” nobody killed; botched evacuation, perhaps on the order of 1,000 killed; slow-motion disaster of replacing clean nuclear power with dirty fossils, more than 10,000 killed. Radiation rarely kills anyone, but fear of radiation kills a lot of people.8

Three Mile Island and Chernobyl

What about the other famous nuclear power accidents?

Three Mile Island was the most serious nuclear power accident in the United States. In 1979 a reactor partially melted down when it overheated, but the containment structure prevented radiation from affecting the surroundings. It was expensive but harmless. Unfortunately, the accident happened just as a fictional nuclear power disaster movie, The China Syndrome, starring Jane Fonda, was captivating audiences. The public saw the reactor accident as proof that nuclear power was a disaster in waiting, as the movie had implied. The fact that the containment structure worked, keeping radiation from leaking, was lost in the wave of panic.

In 1986 in Chernobyl, Ukraine (then part of the Soviet Union), a nuclear power accident struck a reactor that did not have a containment structure. The accident, caused by bad design and a series of operator errors, resulted in significant release of radiation into the environment. The Soviet government tried to keep it secret, and the radiation spread across northern Europe before the government finally admitted the problem. This government response meant that lifesaving actions such as providing iodine pills to local residents did not happen.

How many people died? A few dozen on the scene died, mostly first responders who fought the reactor fire in very high-radiation conditions. The UN experts did their careful studies of the radiation effects and concluded that, most likely, up to “several thousand” people could eventually die from cancer as a result of the radiation exposure, although the increase among a large population would be so small as to be “very difficult to detect.”9

The Chernobyl reactor was eventually encased in a concrete sarcophagus, and an exclusion zone of 1,000 square miles around the plant was evacuated and still has restricted access. Several decades later, scientists studying the exclusion zone are seeing one of the healthiest ecosystems in Europe. The absence of people has done wonders for the animals and plants there, whereas the higher levels of radiation do not seem to have affected them as much, notwithstanding a high initial impact in the most contaminated locations.10 The point is not that everything was okay after the Chernobyl accident—it wasn’t—but rather that the world’s worst nuclear power accident in history was far less deadly than many recent earthquakes, hurricanes, industrial accidents, or epidemics have been. As has been shown since, the vast majority of evacuations from the Chernobyl area had no scientific justification.11

So this, then, is the safety record of nuclear power over more than fifty years, encompassing more than 16,000 reactor-years:12 one serious fatal accident in the USSR with possibly, over time, up to 4,000 deaths; one Japanese “disaster” that caused no deaths; and one American accident that destroyed an expensive facility but otherwise just generated vast quantities of fearful hype. In the United States, nuclear power continues to produce about one-fifth of the nation’s electric supply and has never killed anyone.

How do other energy sources stack up in terms of safety? Start with coal. As long as coal predominates in world energy supply, and even continues to be used in the (natural gas–oriented) United States, the role of nuclear power must be considered as a choice of nuclear power versus coal. Coal replaced some of the nuclear power capacity taken offline in Japan and Germany after 2011. In the United States, the two partly built reactors abandoned in South Carolina in 2017 had been slated to replace the state’s coal plants, which will instead keep operating.13 Environmental groups successfully blocked nuclear power construction in Ohio in the 1970s but stood by quietly as coal plants were built instead, and today that state still mainly uses coal for electricity generation. One Ohio nuclear reactor, 97 percent complete, was actually converted to burn coal after protests and problems stopped construction.14 In Madison, Wisconsin, power is supplied today mainly from a large coal plant, because the nuclear power plant that would have supplied Madison was canceled under political protests decades ago. So nuclear power should be compared against coal as long as coal is still around in significant quantities.

As an order of magnitude approximation, coal kills at least a million people every year worldwide, mostly through particulate emissions that give people cancer and other diseases. They die horrible, painful deaths, but mostly invisible ones, unlike the victims of spectacular events. Of the roughly 10,000 TWh of electricity produced by coal worldwide each year, about 3,000 are in the richer countries and 7,000 in the poorer countries.15 Mortality effects have been estimated at 29 deaths/TWh in Europe and 77 in China,16 which suggests an order of magnitude of 600,000 deaths a year just from coal use in generating electricity. (Other uses of coal such as for heating and industrial power are widespread and also deadly.)

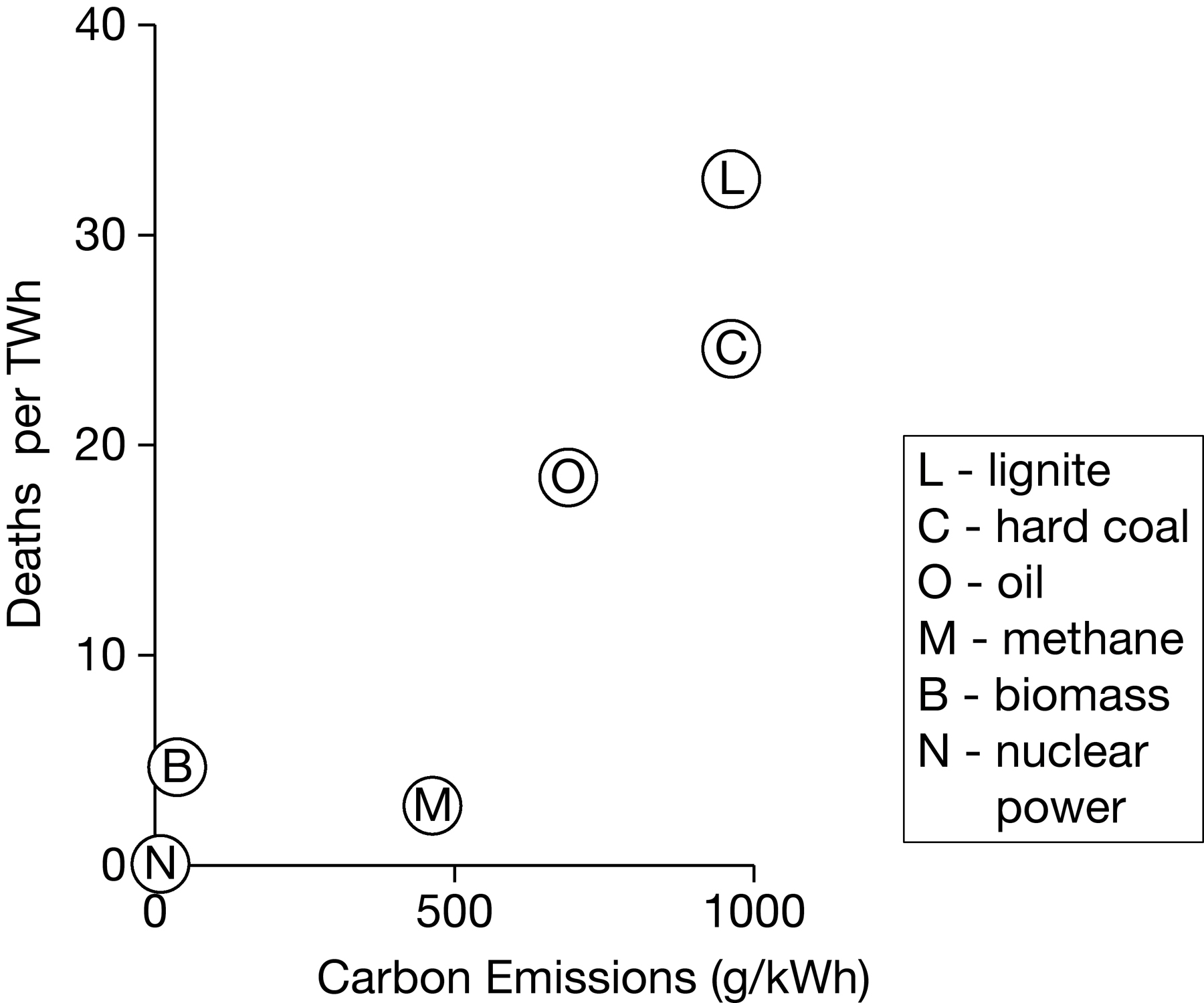

Figure 25. Deaths and CO2 emissions for electricity generation in Europe, by fuel. Source: Anil Markandya and Paul Wilkinson “Electricity Generation and Health,” Lancet 370 (2007): 981. Used by permission.

In addition to its air-pollution effects, coal also has a terrible safety record, from legendary coal-mining accidents (still happening multiple times a year around the world) to toxic wastes around coal plants, generally located near poor communities. For example, in 1972, a failed dam sent a 30-foot wave of coal-waste sludge into sixteen towns in West Virginia, killing 125 people. In 2008 enough poisonous coal ash spilled at a Tennessee power plant to fill a football stadium almost a half mile high—more than the amount of oil spilled in the Deepwater Horizon accident.17 Greenpeace demanded to know whether the authorities could have prevented the accident.18 Why, yes. They could have approved the prototype breeder reactor about 20 miles away that the US Senate killed off in 1983.

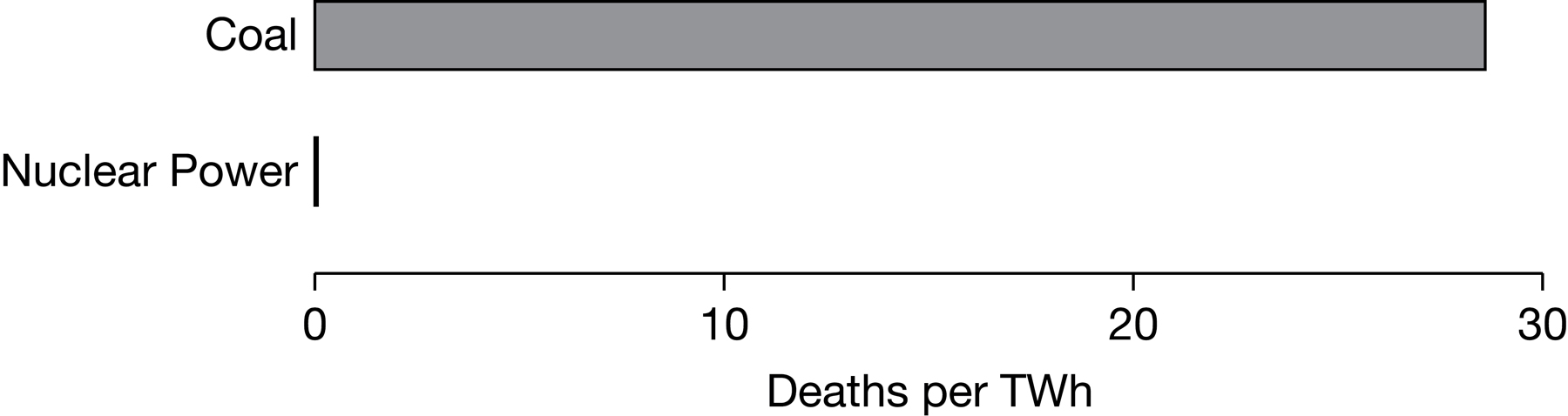

Comparing deaths over the past fifty years from coal against deaths from nuclear power, including Chernobyl and Fukushima, the difference could hardly be more stark—tens of millions from coal and something like a few thousand from nuclear power. A large European study estimates coal deaths for each TWh of electricity at about 30, versus less than 0.1 for nuclear power—hundreds of times higher.19 Over the decades, worldwide, the coal that nuclear power has displaced would have killed more than 2 million additional people—lives saved thanks to the extreme safety of nuclear power.20 Cases of serious illness caused by coal and nuclear power are, in each case, about ten times higher than deaths, meaning hundreds of millions of cases of serious illness from coal pollution in recent decades.21

These safety comparisons are above and beyond the stark differences in CO2 emissions. We would face a dilemma if the predominant energy source that caused vastly more global warming were much safer than the zero-carbon alternative. But it’s exactly the opposite: the clean, zero-carbon energy source is also hundreds of times safer.

Other energy sources, although less dangerous than coal, still cannot touch the safety record of nuclear power.22 Methane gas blows up (see Chapter 6). Oil blows up and spills, as happened spectacularly in the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 (11 killed; 5 million barrels spilled). Oil trains are rolling bombs, as the town of Lac-Mégantic in Canada found out in 2013 when an oil train derailed, blew up, and leveled the town, killing 47 people.

Figure 26. Deaths from nuclear power and coal in Europe per terawatt-hour of electricity. Source: Markandya and Wilkinson, “Electricity Generation and Health.”

Hydroelectric dams are far from safe. If a dam fails, it can flood communities downstream almost without warning. This happened in Banqiao, China, in 1975 and killed 170,000 people. Even in the United States, dam failures killed 2,200 people in 1889, 600 in 1928, and 238 in 1972, among others.23 In 2017 alone, just in the United States, hydroelectric dam crises in California and Puerto Rico forced the evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people.24

Thinking About Radiation

Much of the public’s concern about nuclear power comes down to a gut-level fear of radiation. Radiation is scary because it is invisible, potentially harmful, and associated in the popular imagination with nuclear weapons.25 Radiation created Godzilla, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, and Spider-Man.

Radiation is also a normal part of human existence and varies a lot in daily life. The unit that measures the impact of radiation that people receive is the millisievert (mSv). Background radiation in our daily lives averages around 3 mSv/year, but it varies greatly. Smoking a pack of cigarettes a day adds about 9 mSv/year. Living in Denver or at a similar elevation adds about 2 mSv/year, while working on an airline crew on the New York–Tokyo route adds about 9 mSv/year because cosmic radiation is stronger at high altitude. Granite is radioactive, so living in a granite-rich location increases one’s exposure compared with one near sedimentary soil. Spending all of one’s time in Grand Central Terminal in New York, which is built from granite, would add about 5 mSv/year.26

The highest recorded natural background radiation is received by residents of Ramsar, Iran (where hot springs contain radium), with levels of more than 200 mSv/year. Although scientists and authorities have worried about such a high exposure, no evidence has emerged of negative health effects there.27 There are many other, but less intense, natural “hot spots” around the world.28

Medical procedures also add to radiation exposure and overall account for about a third of the radiation to which humans are exposed (the other two-thirds being natural background radiation). A CT scan of the chest delivers about 7 mSv, in a concentrated time and place, but does not harm health.29 The US Food and Drug Administration sets a limit of 50 mSv in a year for diagnostic procedures in adults. Levels used for treatment are much higher than for diagnostics. Radioactive iodine treatment of thyroid cancer delivers 100,000 mSv to the thyroid and 200 mSv as a whole-body dose.30

Figure 27. CT scans deliver radiation roughly comparable to levels near Fukushima. Illustration: Terese Winslow. Used by permission.

Acute radiation effects kick in around 1,000 mSv, and at a rate of 60,000 mSv/year, the radiation kills half the people in a month.31 So the people living in Ramsar, Iran, seem to do fine at 200 mSv/year, but you might not want to go a lot higher than that. In 2007 the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) recommended dose limits for occupational exposure of “no more than 50 mSv in any one year”32—the same as for medical diagnostics. This is also the exposure limit for those working in a US nuclear power plant.

In the 2011 Fukushima “disaster,” radiation exposure outside the plant itself was low. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated it at 10–50 mSv/year in the most affected areas and 1–10 mSv in the rest of the prefecture. It was orders of magnitude lower in other provinces. Among emergency workers, seventy-five individuals had effective doses of 100–200 mSv and twelve individuals received a dose above 200 mSv, and few health effects have been observed in them. Radiation doses beyond the first year were drastically lower.33 Note that only a few people, and no one in the general population, even exceeded the ICRP recommended occupational dose limit of 50 mSv in a year.

Opponents of nuclear power rely on the “linear no-threshold” (LNT) assumption—that if a lot of radiation is bad, then a small amount is bad in the same proportion. According to this theory, exposure to 10 mSv in a thousand people will cause the same cancer harm as exposure to 1,000 mSv in ten people. The effects are extrapolated down from the very high levels of radiation received by victims of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima in 1945. This does not make any sense, given the similar health outcomes in places with different background radiation, such as Ramsar, Iran. It is a bit like saying that a hundred jumps from a one-foot cliff would have the same health impact as a single jump from a hundred-foot cliff. The human body handles little shocks over time, like many small jumps or small increases in radiation, better than it handles large shocks all at once.

There is even some scientific evidence that small amounts of radiation are actually beneficial.34 But so far, nobody has a generally accepted formula, and nobody knows just what the threshold is, so the linear assumption remains the basis of policy in most places.35 (The ICRP estimates that 200 mSv raises the risk of fatal cancer by 1 percent.)36 One implication is that even a tiny additional dose of radiation in people such as those near Fukushima will translate, over a very large population, to increased cancer fatalities.

According to the LNT approach, exposure to the granite in the perfectly safe Grand Central Terminal—which as mentioned has slightly elevated radiation levels of about 5 mSv/year—is just a mild version of the Hiroshima bombing. With 750,000 visitors per day, if we assume each stays twenty minutes on average, Grand Central is causing two to three cancer deaths each year.37 If it were a nuclear power plant, people would demand that it shut down!

The WHO report on Fukushima conservatively used the LNT assumption. It estimated “lifetime attributable risk (LAR),” which is “the probability of a premature incidence of a cancer attributable to radiation exposure in a representative member of the population.” In the worst case—lifetime risk of thyroid cancer in female infants in the most affected areas of Fukushima province—WHO estimated a 70 percent increase in the thyroid cancer rate as a result of exposure. But this is an increased risk from a very low baseline thyroid cancer rate—below 1 percent—and so represents very few cases. “When the level of baseline incidence is that small, the actual number of ‘extra’ cases is likely to be small also; therefore, the impact in terms of public health would be limited.” The increased cancer risk was much lower for other demographic groups and other types of cancer.38

In the end, then, under the most conservative assumptions and extrapolating extremely small risks to large populations, a few people may get cancer as a result of Fukushima, just as a few may from walking through Grand Central or flying in a jet or living in Denver. Even if true, and it depends on the no-threshold assumption, the number would be far fewer than the thousands who will die from the effects of burning fossil fuels when Japan shut its nuclear reactors after the accident. Nor is there any comparison to the 18,000 killed by the earthquake and tsunami. Furthermore, if our bodies actually can handle low levels of radiation, which after all vary by time and place, and low radiation is not just a small version of surviving an atomic bomb, then nobody will get additional cancer from Fukushima. In either case, the second-worst nuclear power plant accident in history was less lethal than an average coal power plant on a normal day.

Terrorist Attacks

Since the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the public imagination easily conjures up the potential dangers of terrorists crashing airplanes into things. It’s easy for people to imagine that a plane crashing into a nuclear power plant would cause release of radiation if not a meltdown or a giant mushroom cloud! In reality, a nuclear power plant would be a terrible choice of target. First of all, unlike an office tower, it is low to the ground, making the task of hitting it difficult. Second, unlike an office tower, it is made not of a lattice of glass but of thick, heavily steel-reinforced concrete. By contrast, an airplane is lightweight and thin skinned. Third, the important parts—the reactor and spent-fuel pool—are often below ground level. Analysis after 9/11 concluded that a fully loaded Boeing 767 jet would do little if any damage to a nuclear reactor even if it scored a direct hit.39