CHAPTER EIGHT

Risks and Fears

WHY WOULD PEOPLE shut down nuclear power plants over fears of safety but allow coal plants that are far more dangerous to continue operating? Some psychological processes help explain this thinking.1

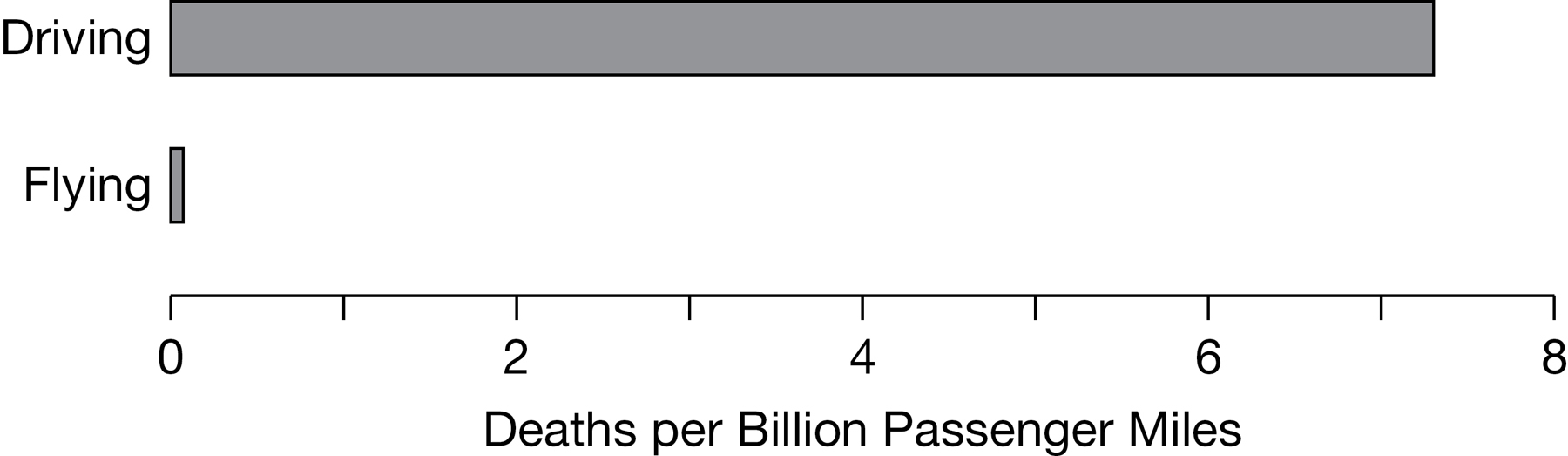

For one thing, people assess risk partly by how memorable or dramatic an event is. People overestimate the probability of events that are easier to imagine or more vivid.2 Driving is far more dangerous than flying, but people fear flying more than driving because a plane crash is large scale and dramatic. After the 9/11 attacks, more people died from driving because of their fear of plane crashes than died on the hijacked planes.3 Similarly, a nuclear power accident is dramatic, especially if everyone panics, and all the more so if a real disaster like Japan’s earthquake/tsunami—or an imagined one like The China Syndrome film—gets cross-wired with it in our minds. (In the few years after the Fukushima accident, anxiety among Japanese citizens declined even though the risk did not change, presumably because the vividness of imagined scenarios decreased with less news coverage.)4 By contrast, most coal deaths happen slowly and in a diffuse way, not even connected to their cause except statistically.

Not only do people generally overestimate the risk from low-probability, high-consequence events, but they do so especially if the events are dreaded—uncontrollable, unfair, and potentially catastrophic events such as plane crashes or terrorist attacks. Nuclear reactor accidents are perceived to be in this category. Fears of nuclear war, which people dread but push to the numbed-out back of their minds, also contribute.5

Unknown or poorly understood consequences, and delays in the effects of events, also heighten fears and exaggerate risks. Nuclear power accidents could spread invisible radiation and cause cancers years later. Merely having more information about these risks does not necessarily reduce fears, however, because anxious people may amass information selectively to buttress their preexisting fears.6

Figure 28. Deaths from driving versus flying, United States, 2015. Source: Ian Savage, “Comparing the Fatality Risks in United States Transportation Across Modes and over Time,” Research in Transportation Economics 43, no. 1 (2013): 14.

Nuclear power triggers risk perception on multiple dimensions. A 1987 review of the psychology of risk perception points to nuclear power as the most salient example of a disconnect between expert opinion and public perception.7 Surveys of Americans regarding attitudes toward risk show “nuclear power to have the dubious distinction of scoring at or near the extreme on all of the characteristics associated with high risk. Its risks were seen as involuntary, delayed, unknown, uncontrollable, unfamiliar, potentially catastrophic, dreaded, and severe (certainly fatal).” By contrast, risks for things like medical X-rays—even when they involve similar amounts of radiation—were judged lower because they were more voluntary, less catastrophic, less dreaded, and more familiar.8

Fear of radiation also rests on people’s anxiety about contamination.9 The fact that radiation is invisible and that few of us really understand it makes it all the more insidious. Yet in truth, radiation is something we are all exposed to every day. Nuclear power contributes trivially compared with other activities such as flying in a jet, living at high altitude, or getting medical scans. Trying to eliminate all radiation because of fear of contamination is like trying to eliminate all bacteria when actually they are part of our healthy ecosystem.

The dangers of radiation form an enduring theme in popular culture, especially in movies. A large number of B-grade horror films since 1950 have used radiation as the device by which scientists gain powers that get out of control and wreak havoc. The typical effect of radiation is to make people or creatures bigger and angrier. The result has been decades of giant ants, octopuses, crabs, lizards, and blobs on the big screen, terrifying audiences and reinforcing fears of the powers of radiation.10

Above all, nuclear power fears are rooted in the Cold War origins of the industry and its connection to nuclear weapons. Especially for baby boomers who came of age in the early Cold War years, “fear of atomic weapons and nuclear fallout… framed the phobia about nuclear power.”11 The two actually have little to do with each other, but historically they did. Fission power was first used for a bomb and then for electric power, and the same technology that produced electric power also gave the United States material for making nuclear bombs. (The opposite is now true, as US nuclear power plants are used to safely consume nuclear weapons material produced during the Cold War.) Whatever the historical connections, a nuclear power plant cannot blow up like a bomb, and fear of nuclear weapons is not an appropriate basis for evaluating nuclear power.

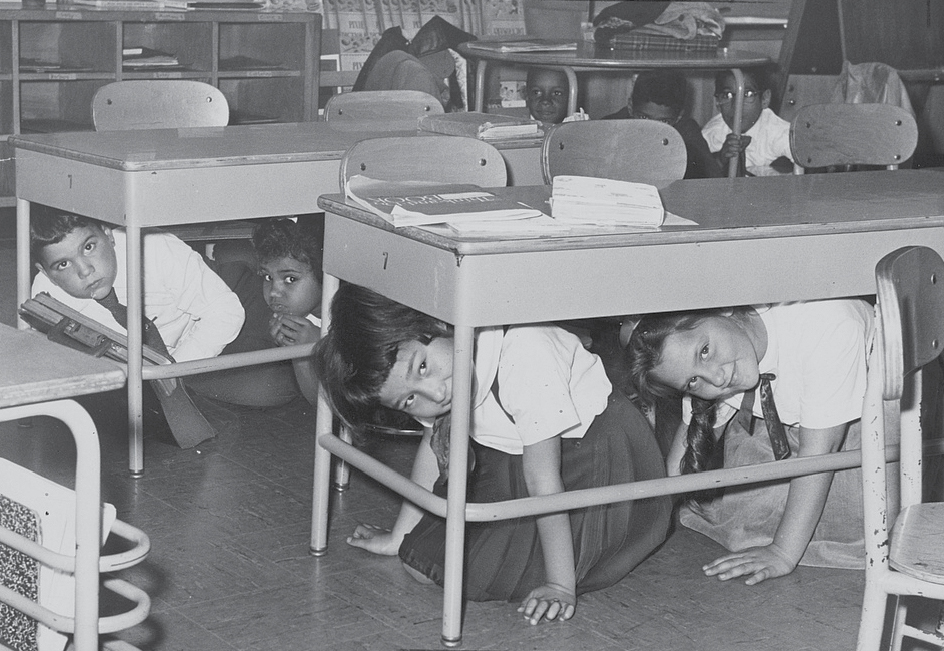

Especially for the generation that grew up hiding heads under desks in fear of a nuclear attack, the very word nuclear is scary. If we think of the merits and risks of kärnkraft, our brains do not react the same way. Unfortunately, the blurring of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the public mind is widespread.12

Regulating Risk

Consider how we regulate risk in commercial aviation. Air travel is very convenient and important to the economy, yet every once in a while, a plane crashes and kills everyone on board. When this happens, we don’t all stop flying.13 Rather, we send in investigators to figure out what happened and try to prevent it from happening again. If a part failed, the industry will inspect or replace that part in all similar planes. If pilot error occurred, airlines might implement new training procedures. As a result, flying has gotten safer and safer over recent decades.

When a company wants to build a new type of aircraft, it designs and builds the plane, gets it certified as safe, and flies it. By contrast, with nuclear power reactor designs, first the design must be approved down to the last detail, at great cost, and then built and certified, all under the careful scrutiny of government inspectors. This adds greatly to the cost. Any change of design or change of safety mandates along the way causes expensive delays and enormous piles of paperwork.

When we fly, we assume a certain level of risk. Same thing when we drive, or walk, or eat food. To reduce these risks, we have sensible government regulations and private insurance policies, and we try to behave wisely. Things are out of balance when the government tries to regulate minute amounts of materials in food that might have a slight tendency to increase disease, while in the meantime 400,000 Americans a year die from smoking. Similarly, we heavily regulate the nuclear power industry to try to make the safest source of energy in history safer still, yet we continue to allow coal, methane, and oil to change our climate and kill huge numbers of people year after year.

Nuclear power might be easier to sell to a frightened public if there were more accidents. Then it would look more like commercial aviation—yeah, people sometimes die, but it’s way safer than the alternative. There would be relative risks to compare. But when nuclear power already is so close to zero risk, there is nothing to compare. Companies promote new designs (or governments contemplate new regulations) that can increase safety an order of magnitude—from extremely safe to very extremely safe. It’s a losing proposition, because you can never reach zero risk for anything. Trying to do so just drives up costs exponentially, which is what has happened to nuclear power since Three Mile Island. In any real-world policy, zero risk means infinite cost.

Consider another example of risk, again from Sweden—the reduction of road fatalities. Sweden, the home of safety-oriented car maker Volvo, invented the modern three-point seat belt, now a global standard, and has for decades devoted enormous efforts and funds toward reducing traffic-related deaths. In the 1980s, around 1,000 Swedes died every year in traffic. In 1997 the Swedish government’s “Vision Zero” plan promised to eliminate road fatalities and injuries altogether, and safety measures have now reduced deaths to around 260 per year. Safety has priority over speed or convenience, with lowered speed limits in urban areas, increased speed regulations, checks, cameras, speed bumps, improved road railings, and many other costly and sometimes cumbersome changes. These measures have succeeded, but 260 is still more than zero. “We simply do not accept any deaths or injuries on our roads,” said the national transportation agency.14

At what point are massive efforts to further reduce the number toward zero simply not worth the cost, given that societies have many other social problems that deserve attention and funds? Might the efforts save more lives if directed to other proven mitigation strategies (such as reducing smoking or obesity) instead of focusing narrowly on traffic deaths?

The issue of nuclear power safety is a far more extreme example of the traffic safety problem. Already by far the most tightly controlled, regulated, and safest form of large-scale energy production in the world, nuclear power faces a never-ending escalation in costly safety requirements that harm both public perception and economic competitiveness. The “Vision Zero” for nuclear power has already been achieved, as illustrated by the zero death toll at Fukushima, yet further increasing nuclear power safety at any cost is a high priority. This is the traffic equivalent of lowering the allowable top speed for “nuclear cars” from 1 mph down to 0.1 mph, while allowing “coal cars” to drive without speed limits or brakes.

In 1975 US nuclear power regulators issued a detailed risk analysis of nuclear power plant accidents, concluding that with one hundred nuclear power plants operating, the chances of any fatal accident were below 1 in 10,000, and the chances of an accident killing a thousand people were 1 in 1 million—orders of magnitude below the risks for air crashes, fires, and dam failures.15

Antinuclear groups strongly contested such assessments. In 1977 the Union of Concerned Scientists claimed that in fact nuclear power accidents could cause 14,400 fatal cancers by the year 2000, and the chances were 1 in 100 of an accident killing 100,000 people.16 Although the 1979 Three Mile Island accident did not harm the public, it reinforced such fears and led to a near-shutdown of US nuclear power plant construction, with electricity being instead supplied by coal and other fossil fuels. Now, decades later, nobody has died, yet antinuclear groups continue to demand more and more reductions of already tiny risks. As a result, the world has failed spectacularly to address the real risks—coal deaths and climate change.

Indeed, the world seems to have lost a “can-do” attitude toward nuclear power that met great success in earlier decades. The earliest reactors were built quite successfully in just a few years with far fewer resources and knowledge than we now have. The US Navy put hundreds of reactors at sea with barely a problem and did it quickly, starting from scratch. Sweden and France built affordable nuclear power plants that today’s efforts seem unable to match. We now use computers instead of slide rules, we have much better-educated populations, our GDPs have multiplied, and we have engineering methods and materials that our grandparents could only dream of. Despite all that, much of the world seems to be frozen in fear—fear that is not reality based but that is really killing us.

“The ultimate question,” wrote physicist Alvin Weinberg after Chernobyl, “is whether we can accept a technology whose safety is measured probabilistically. Members of the nuclear community had always assumed that if the probability of a severe accident was sufficiently low, nuclear power would be accepted.”17 This assumption of the public’s ability to assess risk was perhaps unrealistic.

Of the many people who feel that nuclear power is just “too dangerous,” surprisingly few ever ask, “Compared to what?” It’s pretty dangerous compared with fairy dust, which meets the world’s growing energy needs without any costs or risks. But compared with the world’s leading, and fastest-growing, power source—coal? Compared with oil and gas?

In thinking about nuclear power safety, one should always ask, “Compared to what?” And the answer is: compared to coal—the world’s dominant and fastest-growing fuel, the leading cause of climate change, the fuel that kills a million people a year. Compared to that.

Scary Versus Dangerous

Scary and dangerous are not the same thing.

Jumping off the top Olympic high-dive platform, 33 feet high, would be scary for many of us. But it would not be particularly dangerous, assuming you can swim. The risks—of landing badly and injuring ourselves or even panicking and drowning—are not zero but quite small.

But now imagine you are on a long railroad bridge, 33 feet above a deep body of calm water, and a train is coming across the bridge at you. The jump is still scary. But it’s the train that’s actually dangerous. If you freeze in fear and don’t jump, you will die. And if you start running away from the train, figuring that although you can’t make it off the bridge, at least you are moving in the right direction, you will also die.

This is humanity’s situation: Climate change is the train coming down the track at us, likely to cause catastrophic harm. The popular responses—ramping up renewables, moving from coal to methane, and such—move us in the right direction but do not get us off the bridge in time. We have a solution that works, that Sweden and others have proven, and that’s no more dangerous than jumping off that bridge, but it’s scary. That solution is to rapidly expand our use of nuclear power.

Figure 31. Jumping is scary; staying on is dangerous. Photo: Drew Jacksich via Wikimedia Commons (CC Attribute-Share-Alike Generic 2.0).

For many people, nuclear power is scary, but it has an extraordinary safety record over fifty years. Understanding the difference between scary and dangerous, between jumping in the water and being run over by a train, may be the key to our future.