CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Act Globally

THE EXAMPLE OF Sweden shows that rapid decarbonization is possible. As one physicist put it recently, “Solving global warming does not require us to ‘tear down capitalism.’ The world just needs to be a bit more like Sweden.”1 Sweden’s success has actually been multifaceted—resulting from a mix of plentiful hydropower, an early decision to reduce fuel imports, and a culture that values efficiency. But the main driver of success, shifting from fossil fuels to nuclear power, has been successfully implemented in other countries as well, notably France.

Although the 1970s and ’80s saw Sweden, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Finland quickly build out their nuclear power capacity, the model is not limited to Europe or to that time period. The Canadian province of Ontario shows the feasibility, in this century, of replacing coal with nuclear power.2 With a population of 14 million, somewhat larger than Sweden’s, Ontario is the industrial heartland of Canada. When it rolled out nuclear power plants, it built 16 reactors in seventeen years, 1976–1993.3 Then in 2003–2014, it upgraded the province’s nuclear power stations to bring nuclear power from 42 percent to 60 percent of the total (hydropower supplied most of the rest). In 2014 Ontario closed its last coal-operated power plant. In one decade, CO2 emissions from Ontario’s electric sector had fallen by almost 90 percent, with fossil fuels (all of it now methane) reduced to a small fraction.4

The model could be replicated around the world.5 As we have seen, a country such as South Korea or Russia that pursues nuclear power expansion as a national policy can quickly produce nuclear reactors one after another, safely and economically. The director of the IAEA recently estimated the global investment needed to build 10–20 new reactors annually at $80 billion per year—more than doubling nuclear power capacity by 2040.6 This is equivalent to one-tenth of 1 percent of the world’s annual economic activity, is an investment not an expenditure, and is readily achievable given the political will. But actually, at $4–$8 billion per reactor, the price is probably higher than necessary, given that South Korea can build one for $2 billion per gigawatt today,7 and the costs would come down in a period of repeated builds and economies of scale.

The idea of a large-scale world build-out of nuclear power as a response to climate change is still controversial but receiving new and serious attention from experts as the climate crisis gets worse.8 Nuclear power risks are far smaller than climate change risks. In 2015 four leading climate scientists, who understand the climate risks, argued that “the only viable path forward” was an “accelerated deployment of new nuclear reactors” alongside the growth of renewables. Pointing to the examples of Sweden and France, they note that building 115 new reactors each year would entirely eliminate fossil fuels from the world’s growing electricity production by 2050.9 This scale of action, much more ambitious than that of the IAEA director, is the scale on which we should be thinking.

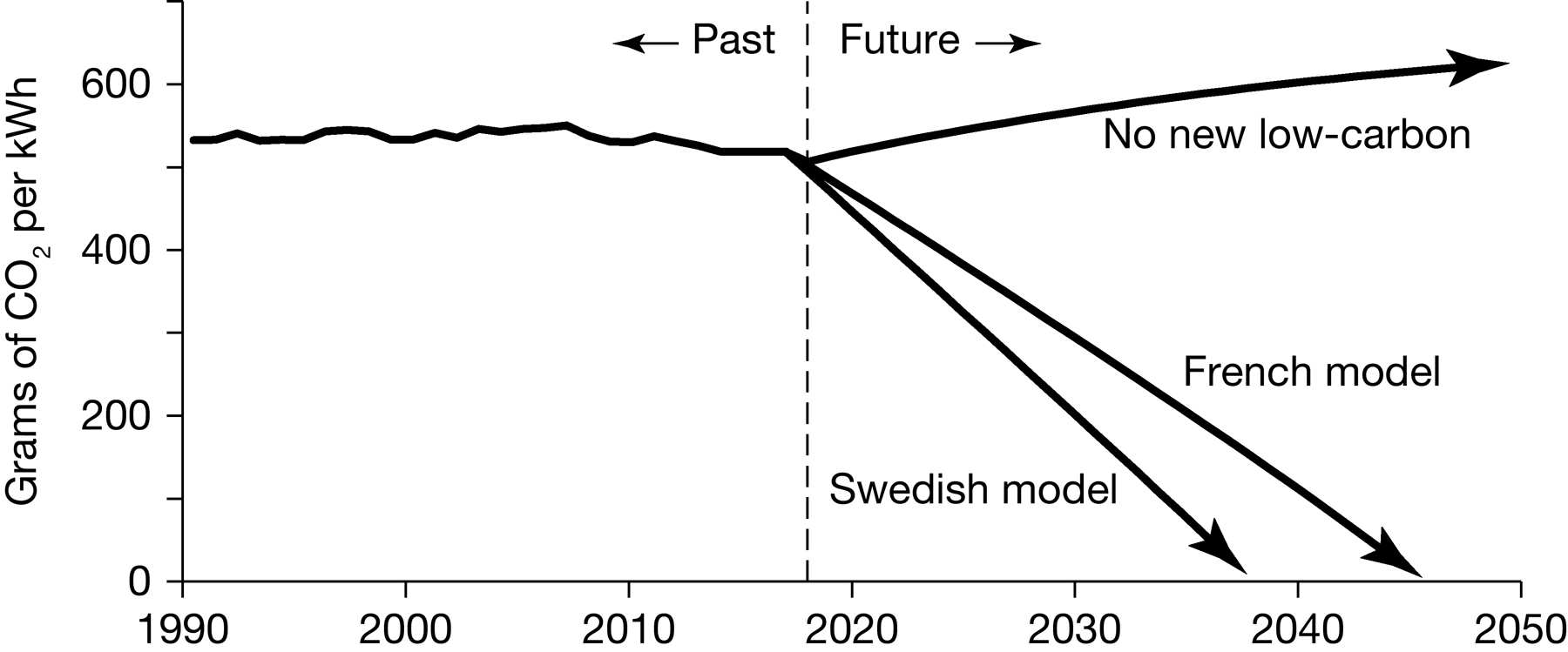

Figure 53. Carbon emissions intensity (per unit of electricity) worldwide, with no new low-carbon power and if low-carbon installations were built at the historical GDP-normalized rates of Sweden or France. Data source: International Energy Agency (emissions intensity and demand projection), OECD (GDP projection), and BP (electricity generation data).

Building 115 reactors per year may seem a large undertaking, but to put it in perspective, the Swedes had no problems building about 1 reactor per ten million inhabitants per year in the 1970s and early 1980s. That rate, applied globally today, would produce about 750 reactors each year, more than six times the proposed rate. At even half Sweden’s rate, the world could eliminate fossil fuels from electricity generation by 2040 instead of 2050, and displace coal as a heat source for buildings and industrial use, and have electricity for energy-intensive applications such as producing fossil-free liquid fuels or sequestering CO2 from the atmosphere. Many millions of lives would be saved, and billions of people would be economically uplifted. We know from cases like Sweden and France that this is doable, and we have much better technology and knowledge to do it now than they did several decades ago.

Because coal is the number-one problem for climate change, and coal generates round-the-clock power, an intensive program to build nuclear power plants worldwide is the most effective solution. Such a program cannot succeed haphazardly. It has to be a national decision, or countries will get stuck in the US-style swamp of too many designs and too little experience building them, with costs escalating.

Standardized design is a key aspect. In 1995 the head of the US NRC summed up the difference between the French and American nuclear industries thus: “The French have two kinds of reactors and hundreds of kinds of cheese, whereas in the United States the figures are reversed.”10 Other important elements for fast, low-cost construction are multiple builds of the same design to gain experience with it, siting multiple reactors at one location, strong government support, and centralized policy making through a single utility or agency.

China is a key player. It could pick a limited number of standardized designs and concentrate on a large-scale short-term expansion to phase out coal. (Stopping Chinese coal burning is the immediate top priority to save the planet.) At the same time, China could keep experimenting with a few fourth-generation designs to find out what will best follow in a decade. Replacing China’s coal plants with nuclear power plants, at a Sweden-style pace, could be the single most important action anyone could take to combat climate change worldwide.

In the countries of the West, those with existing nuclear reactors could immediately stop shutting them down ahead of their useful life. Although limited in scale, this would be the cheapest, quickest way to get CO2-free electricity. Countries where building more of the same appears hopeless from a political perspective, such as the United States and Germany, could get behind a few fourth-generation designs and build them out rapidly. The first nuclear reactors in history, such as Admiral Rickover’s, were designed and built in a few years. Today we have more money, much better technology, and a better-educated workforce, so we can do at least as well.

Countries that can still build practical, affordable third-generation reactors, such as South Korea, could build out the fleet to power the country and get off fossil fuels, while exporting to other countries (as South Korea has done successfully in the UAE).

Russia could also step up its construction of new plants, continue to push its exports, and move forward aggressively with its fourth-generation Breakthrough technology development.

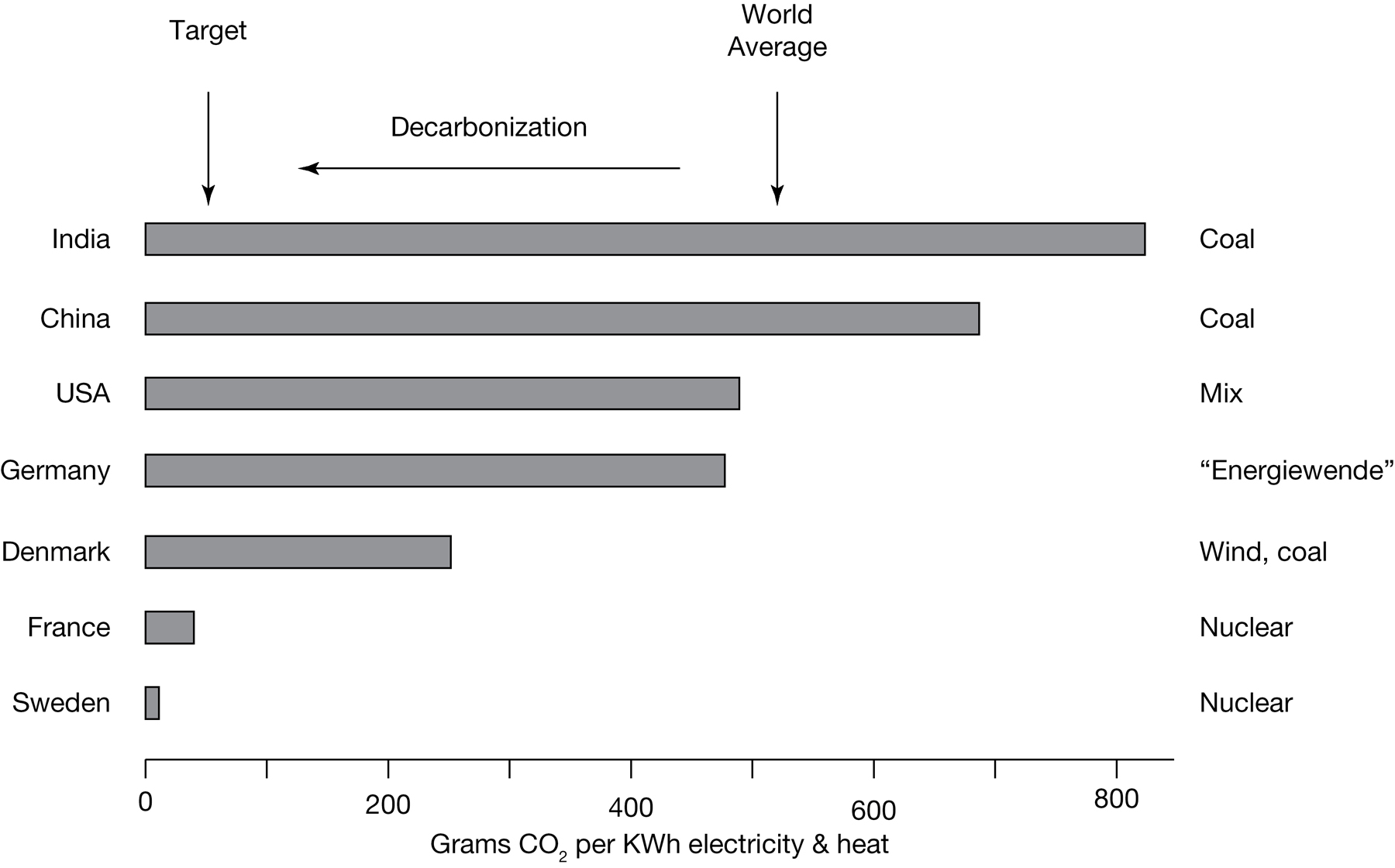

Decarbonization requires moving the world’s electricity generation system rapidly from a carbon-intensive model, currently over 500 grams of CO2 per kWh produced, to one with a tenth that level of carbon pollution per kWh. France, Sweden, and Ontario have done just that; others are nowhere near and need to catch up.

Figure 54. Carbon intensity of electricity in different countries. Data source: International Energy Agency data set (emissions per kWh of electricity and heat output).

Revamping the Economy

Beyond replacing coal and methane on the electric grid, we need to decarbonize across the economy. Of course, we want economic growth to continue, particularly in the poorer countries, but decoupled from fossil-fuel use.11 As a very rough rule, energy today divides into three main parts—electricity, transportation, and heat. One simple formula for cleaning up the economy and getting rid of fossil fuels is this: (1) generate electricity cleanly; (2) electrify everything.12

Figure 55. Electrify everything: Siemens is testing an electric highway for heavy trucks in Sweden. Photo: Courtesy of Siemens. www.siemens.com/press.

This transition is under way already. Electric trains have replaced diesel trains in many countries. Hybrid and all-electric cars are growing, and several countries have declared a goal to eliminate gasoline and diesel cars. Around the world, research on batteries and other aspects of electric cars can accelerate the transition from fossil to electric vehicles. The steel industry (in Sweden) has invented a new method to use electricity rather than coal in making steel.13

Sweden has also switched over to a combination of electric heating, notably with heat pumps, and “district heating” to heat multiple buildings at once, more efficiently and cleanly (biomass plays an important part in district heating). Perhaps the American suburbs will never be able to use district heating, but cities can, and even in the suburbs electric heat pumps are already growing in popularity and coming down in cost.

While electrification will undoubtedly be a main route to decarbonization, there are also great opportunities to directly supply cleanly produced heat. Conventional nuclear reactors are very well suited to supply heat to district heating networks, something that is already happening at fifty-seven reactors around the world, mainly in Russia. China has just finished construction of a novel high-temperature gas-cooled reactor14 that can produce steam at 567°C, far higher than in conventional light-water reactors. The very high temperatures mean that electricity production is highly efficient (42 percent), and they also allow high-temperature industrial process heat supply, directly displacing coal plants at industrial facilities.

Another alternative to straightforward electrification is to create liquid and gaseous fuels to replace fossil fuels. This could be especially useful if cheap batteries prove elusive. Nuclear electricity could split water into hydrogen and oxygen, and that hydrogen gas could replace methane (with modifications to existing infrastructure).15 Hydrogen is just methane without the carbon. Nuclear power could also be transformed into ammonia as an energy carrier, since ammonia contains only hydrogen and nitrogen, readily obtainable from water and air if you have energy.16 Ammonia is energy denser than hydrogen and can be stored at lower pressures. Using nuclear power to create liquid or gaseous fuels has the advantage that the round-the-clock power of the reactor could be used for energy on the grid when demand is high and for fuel production when grid demand is low. This could also help integrate renewables onto the grid, as nuclear power could work around their ups and downs efficiently, producing liquid fuels when renewable production is high and grid electricity when renewables drop out.

Finally, serious carbon pricing would help revamp the economy away from fossil fuels. International agreements to standardize carbon prices across borders would make this easier to administer, provided the price was high enough to bring about the needed changes.

Politics

Ultimately, replacing fossil fuels with nuclear power is a political as much as a technical issue.17 Politics does matter; if nuclear power is too problematic politically, it won’t be able to make a difference. Even in Sweden, politics is threatening the success of nuclear power. In 2016 a government that included the Green Party wanted to phase out nuclear power, although in the end a compromise deal was reached that limits the damage to the Swedish electricity supply and the climate. However, current policies are still driving four well-operating Swedish reactors into very early retirement in the next few years.18 A premature shutdown of the country’s full nuclear power capacity would take clean energy off of a northern European grid reliant on German and Polish coal plants, leading to an estimated 50,000 energy-production-related deaths.19

Thinking about a potential major expansion of nuclear power worldwide, is politics really such a big constraint? China, the most central player for rapid decarbonization, is a one-party state where antinuclear organizations have little leverage. Russia, the key player in both current exports and fourth-generation technology, is also authoritarian and supportive of nuclear power.

If countries such as Germany and Japan want to shut off nuclear power and burn methane and coal instead, this is certainly a step backward for climate efforts but hardly a death blow for the prospects of a nuclear power build-out.

The United States is perhaps the most problematic case because it is the original source of nuclear expertise and today generates more total nuclear power than any other country, with twice the production of second-place France.20 The lagging state of the US nuclear power industry is much more of a concern than the problems in other Western democracies. American politics has challenged the nuclear power industry for decades, with antinuclear groups being large, well-funded, and very active in lobbying, shaping public opinion, and litigation. As we have seen, in a supreme irony, the very groups most actively opposing nuclear power are those most vocal about climate change. On the hopeful side, there is a growing pronuclear wing of the environmentalist movement21 and literature22 in the United States, although it is still quite small, entirely reliant on private donations, and has access to just a tiny fraction of the financial resources of the antinuclear movement.

American politics are not, however, altogether unfavorable to a nuclear power expansion. States have begun to realize that existing nuclear power plants play a key role in meeting emissions targets and have begun in a few cases to treat nuclear power on a more level playing field with renewables. This trend could lead to a shift from Renewable Portfolio Standards—state mandates to include a certain percentage of renewables in the energy mix—to Low-Carbon Portfolio Standards that include nuclear power along with renewables.23

There is also some bipartisan consensus regarding clean energy, which receives considerable support even from the right of the American political spectrum. Archconservative governor of Kansas Sam Brownback was a big supporter of the large-scale expansion of wind power in that state. It was good for the Kansas economy. Other top wind-power states are also mostly Republican leaning.24 And concerns about climate change, although taboo among Republican elected officials, are actually strong among rank-and-file Republican voters, with about half saying they would be more likely to vote for a candidate who supports fighting climate change.25

Nuclear power, especially for fourth-generation designs, has considerable bipartisan support in the US Congress. Liberals are becoming more open to nuclear power because of climate change, and conservatives support it for such reasons as economics and US superiority in technology.26

The antinuclear movement has progressed through reasons to oppose nuclear power, one after another. First, it was that nuclear power was too dangerous, but after fifty years with an exemplary safety record, this argument gets thin. Next, nuclear power would lead to the proliferation of nuclear weapons, including to terrorists. Again, the record shows otherwise.27

Then it was that nuclear power was simply uneconomical because US and European efforts to build new plants came in way over budget and behind schedule. These economic issues, which we address shortly, were partly the result of the constant litigation and regulatory demands of the antinuclear groups themselves. Nuclear power in Sweden has been highly competitive for decades, and in places like South Korea newer plants are similarly affordable.

Figure 56. German antinuclear protesters, 2011; no such enthusiasm to stop coal. Photo: Rot-Braun Magdeburg via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0).

The next antinuclear argument was that “we don’t need nuclear power” because renewables will solve everything. But in every case where nuclear power was shut down, renewables have not filled the gap and CO2 emissions have gone up,28 whereas in places such as Ontario that expanded nuclear power, emissions went down.

In the end, those who have spent decades making nuclear power politically unpopular argue that a nuclear power expansion is simply politically infeasible. This is just a self-fulfilling prophesy, and we should not be so quick to write off the most practical solution for humanity’s most serious problem as politically undoable. Politics have a way of catching up with necessity.

The political problems that appear most challenging are specific not to nuclear power but to tackling climate change itself. As we have seen, the international community’s best effort to date, the 2015 Paris Agreement, does not come very close to solving the problem and, even for its inadequate goals, does not have any enforcement mechanism for each country’s voluntary commitments. In fact, many countries are falling short of their Paris commitments, yet the international political system does not have a mechanism to correct this, much less to push them further in the right direction.29

Think again about the idea of a large asteroid heading for a collision with Earth. Would we ask countries for voluntary contributions and then let them fall short without consequence? No, we would create international structures and processes to reliably solve the problem, drawing on all the world’s available talent and resources.

Economics

The argument that nuclear power these days is “too expensive” ignores the places where nuclear power has been cost competitive, such as in South Korea, Russia, and of course Sweden. It also ignores cases such as Vermont Yankee, where nuclear power plants have closed long before their licensed end dates, despite producing energy more cheaply than any source other than methane. Environmentalists who oppose nuclear power demand short-term profitability without subsidies but make no such demand on renewables. Nuclear power plants require large up-front investments but then produce large amounts of clean power for sixty years or more, several times the life span of wind or solar installations.30 Nuclear power does not require expensive storage because it is not intermittent. Without a carbon price, nuclear power does not compete with cheap German coal or US methane, but it can be cheaper than most renewables without their subsidies.31 And in South Korea in 2013, nuclear power generated electricity at 3.7 cents/kWh, cheaper than coal (5.6 cents), hydro (16.2 cents), or LNG (20.5 cents).32 “Too expensive” clearly does not justify environmentalist demands to shut down South Korea’s nuclear power plants.

Large capital expenditures at the start of a long-term project such as a nuclear power plant do not come easily in a deregulated private marketplace, especially when prices of competing fossil fuels are unstable. Also, the discount rate, discussed above in regard to carbon pricing, strongly affects the economics of a long-term investment such as a nuclear power plant. One analysis of the cost of energy in Western industrialized countries, “levelized” over the whole life cycle of the technology from mining to decommissioning, found that at a 3 percent discount rate, nuclear power came in cheaper than coal or methane. But at a 10 percent discount rate, it lost that advantage.33

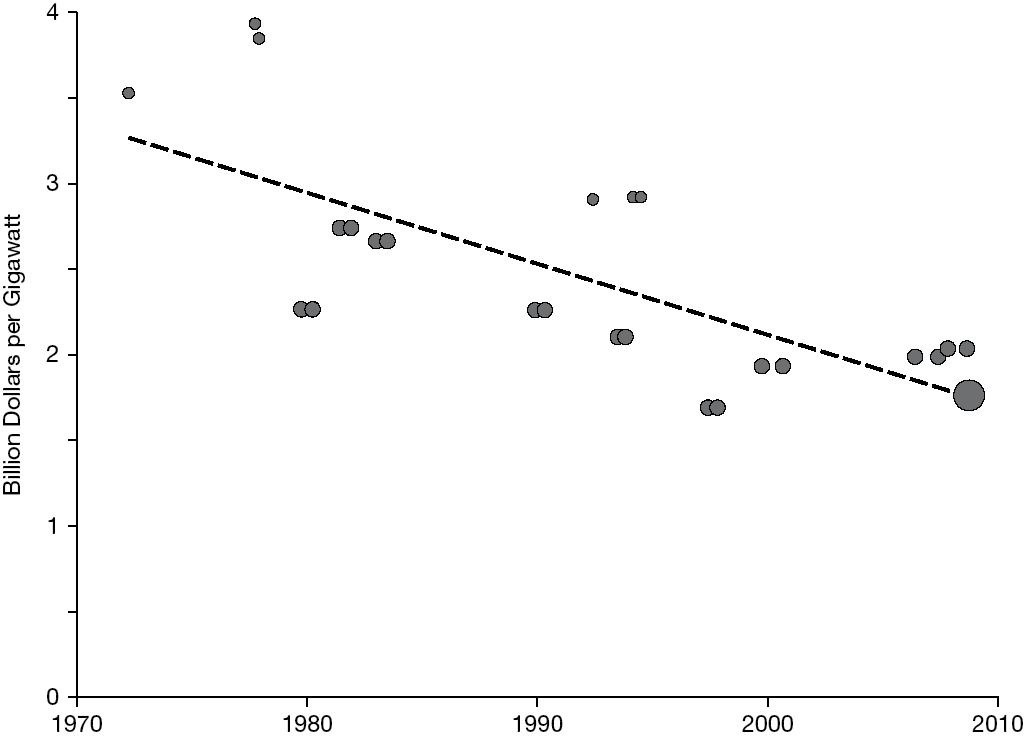

In some ways building a nuclear power plant is more like building a railroad than a gas station, and long-term government support has been important to ensure the success of such large-scale long-lived projects in an unstable market.34 South Korea generates cheap electricity because, with repeated builds, it can construct a nuclear power plant for about $2 billion per gigawatt. In the United Kingdom, it now costs $8 billion per gigawatt, and in the United States the latest attempt runs to around $12 billion.35 This does not mean nuclear power is “not economical” but rather that Britain and the United States should start to do what South Korea did—build successive plants of the same design with government backing for the long-term investment. A recent study of cost drivers in nuclear plant construction around the world emphasizes efforts to capture learning during the buildout of a fleet and completion of designs prior to the start of construction.36

Figure 57. Nuclear power plant construction costs in South Korea, 1972–2008. Dot sizes indicate capacities of 558–669 MW, 903–1,001 MW, and 1,300+ MW. Data source: Courtesy of Jessica Lovering based on Jessica R. Lovering, Arthur Yip, and Ted Nordhaus, “Historical Construction Costs of Global Nuclear Power Reactors,” Energy Policy 91 (April 2016): 371–382.

Beyond Costs and Burdens

To date, the international politics of climate change have been framed far too much around a narrative of burden sharing. We assume that the solution to a future disaster will be expensive to the present generation and that the international community’s big role is to allocate those costs among the world’s sovereign countries. This approach guarantees that everyone wants someone else to pay the costs and that today’s inhabitants of Earth will want to put off costs to an indeterminate future.

How could this narrative be reframed away from costs and burdens and toward opportunities and inventions? Swedes are not moping around suffering from burdens because they cut their CO2 emissions. On the contrary, their economy is robust, they are healthier with cleaner air, and they use plenty of energy to stay warm and well lighted in the Scandinavian winter. Similarly, people who drive electric cars do not suffer because the cars perform badly but, at least, pollute less. Not at all. Electric cars are fun to drive, and hundreds of thousands of people have lined up to buy Tesla Model 3s before the first one was even produced—not because we all want to suffer to save the world, but because Teslas are cool. With nuclear power and renewables together, we have the opportunity to make energy available to poor people around the world, which should lead to better health, less armed conflict, and lower population growth. Those are good things.

Figure 58. Electric cars and other energy innovations are fun, not burdensome. Photo: Courtesy of Steve Cole.

Energy innovation generally means more fun.37 We love our smartphones and don’t miss the room-size computers they replaced. Self-driving cars will make transportation more efficient and make our lives more productive. Fourth-generation nuclear power plants will make our electricity not only cleaner but also more economical. These trends happen in conjunction with decarbonization, not contrary to it. We need to replace the mind-set of sacrifices and trade-offs with a mind-set of solving problems and achieving win-win outcomes.

In Sweden it’s simply not the case that climate solutions come at the expense of business, or that addressing climate change means fewer resources for other social issues, or that environmentalism takes a toll on the economy. None of that is true. Sweden is not only the country with the most nuclear power per person in the world. It is also number one on the Ecowatch Global Green Economy List and number three on the Yale-Columbia Environmental Performance Index.38 And it is number one on the Forbes list of Best Countries for Doing Business.39

Think about that: the greenest country is also the best for business.

For innovation, Sweden is ranked at or near the top.40 It ranks highly for gender equality, lack of corruption, care for elders, and support for children and parents. As one World Economic Forum blogger put it, Sweden “beats other countries at just about everything.”41

Does Sweden perform so well because it is number one in using nuclear power? Obviously not. But does nuclear power contribute to success rather than burdening Swedes? Clearly, it does. Think Swedishly, Act Globally.

Sweden is not an anomaly, though. It just makes a good example of many pieces working together to decarbonize an economy. Norway has more electric cars. South Korea makes cheaper reactors. Finland has a more advanced waste repository. Russia has better fourth-generation nuclear technology. China is more committed to building new reactors. The United States has more private start-ups. France has a better-developed fuel cycle. India, Canada, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, Vietnam, Egypt, Bangladesh, and more are taking steps that could contribute to a viable path to actually solve climate change.

The example of countries that have harnessed nuclear power along with renewables proves that we can rapidly decarbonize and prosper economically and socially. We can have low CO2 emissions, clean air, economic strength and social justice in rich countries, and abundant energy for development in poor ones. Saving the planet is not a burden to share, but a chance to reinvent ourselves for the better.